INTRODUCTION

Urban neighborhoods like historic Ward 7 in Philadelphia have historically been plagued with poverty, crime, and a dearth of physical spaces to engage in physical activity and healthy eating, and social spaces to improve social and cultural capital (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1899). Over time, however, Ward 7 became gentrified as urban Blacks were pushed north of the city (Hunter Reference Hunter2013). Other neighborhoods around the country similar to Ward 7, however, continued to experience spiraling economic decline. These neighborhoods tend to have under-funded schools and are more likely to be predominately Black and/or Hispanic (Charles Reference Charles2003, Reference Charles2006). Unfortunately, neighborhoods such as these are pervasive throughout the United States from the south side of Chicago to Orange Mound Memphis to Sandtown Baltimore to Wards 7 and 8 in Washington, DC.

Impoverished urban neighborhoods and poorly performing schools have been the scientific laboratory for sociologists, public health scholars, and education practitioners alike. Rightfully so, researchers desire to better understand the plight of the urban poor (Wilson Reference Wilson1996). Research shows that racial segregation and a lack of economic opportunities are the main drivers of poverty (Charles Reference Charles2003, Reference Charles2006; Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1993). Predominately Black neighborhoods have higher levels of pollution, more crime, fewer green and walkable neighborhoods, fewer trees, and worse schools than predominately White neighborhoods (Charles Reference Charles2003, Reference Charles2006; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Munoz and JaJa2016; La Veist et al., Reference LaVeist, Pollack, Thorpe, Fesahazion and Gaskin2011; La Veist and Wallace, Reference La Veist and Wallace2000; Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1993; Sewell Reference Sewell and Ray2010). Arguments for why schools underperform, however, have primarily highlighted causes such as broken families, oppositional culture and “acting white,” and lack of school resources (Downey Reference Downey2008; Fordham and Ogbu, Reference Fordham and Ogbu1986; Harris Reference Harris2011; Kozol Reference Kozol2006; Lewis Reference Lewis1959; Lewis and Diamond, Reference Lewis and Diamond2015; Lewis-McCoy Reference Lewis-McCoy2014; Moynihan Reference Moynihan1965; Tyson Reference Tyson2011).

Scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois desired to not only illuminate the social ills of impoverished communities but to think of innovative ways to reduce social inequities present in urban America. Starting with a series of resolutions on the plight of Black schools, Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1901) conducted one of the first systematic investigations on the segregated educational system in America. In one of his signature, groundbreaking Atlanta School studies, Du Bois highlighted inadequate structural conditions of Black schools and the lack of proper training for Black teachers. Using data from the state school reports, the Freedman’s Bureau, and surveys from schools, this study found that only one out of 100 Black students were engaged in satisfactory secondary education. While the number of Black schools and colleges increased in the late 1800s, they did not keep pace with the resource increases allocated for White schools. Du Bois concluded his report by issuing a call to Congress to not only change Southern schools for Blacks but for southern Whites as well who were falling behind their Northern counterparts.

Du Bois’s work continues to be extremely timely. Although his words were written over one hundred years ago, the disparities he discovered then are still prominent in the twenty-first century. Du Bois stated, “Education is that whole system of human training within and without the school house walls, which molds and develops men” (Aberjhani 200, p. 69). In this statement, Du Bois highlights that the social and physical environments outside of schools matter for learning. Existing research shows that due to environmental disparities in school and neighborhood contexts, Black and economically-disadvantaged children spend less time in activities that promote cognitive, social, and physical capabilities (Bohnert et al., Reference Bohnert, Fredricks and Randall2010; Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Waite, Brooks-Gunn and Reiss2011; Hofferth and Moon, Reference Hofferth and Moon2012). Du Bois argued that Black youth needed to be educated in exceptional Black schools like those afforded to Whites. He asserted that writing, reading, math, and thinking skills were fundamental to this cause.

Similar to Du Bois, pragmatist John Dewey believed that improving the social and physical environment would lead to better education opportunities and inevitably decrease inequality. Schools like the Harlem Children Zone, which takes a holistic approach to learning by focusing on aspects inside and outside of the school walls, show the importance of tackling the social and physical environment around schools. Dewey specifically highlighted school gardens as physical and social environments to improve learning. Scholars have found that learning in school gardens positively influences academic achievement (Blair Reference Blair2009; Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013; Klemmer et al., Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005a, Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005b; Williams and Dixon, Reference Williams and Scott Dixon2013) as well as nutritional habits (Nanney et al., Reference Nanney, Johnson, Elliott and Haire-Joshu2006) and exercise habits (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Rickinson, Teamey, Morris, Young Choi, Sanders and Benefield2006). To date, however, limited attention has been paid to understanding how the relationship between the presence of gardens in schools and academic achievement is linked to reducing race and class inequality. Our paper aims to fill this gap by studying school gardens in one urban setting, Washington, DC, where the school system has a formal school garden program.

Our study examines how the Washington, DC School Garden Program serves as a potential gateway to reducing the achievement gap. We ask: Is the presence of a school garden in a school positively associated with student test scores in math, reading, and science? Do school gardens help to attenuate the association between race and social class composition and academic achievement? Underscoring the fact that there are few studies that specifically focus on ways to engage non-Whites in environmental activities, and even fewer that hold constant social class and compare across racial groups to assess how environmental activities matter in urban spaces, our paper aims to fill important gaps in the literature on the environment, education, and social inequality. Accordingly, our study builds on the work of Du Bois to not just highlight social problems but to think of innovative ways to solve them.

In the sections to follow, we first conceptualize the environment as having physical, social, and built dimensions, especially in urban areas. Second, we provide details on the school garden movement and why it may be a key component for reducing gaps in education and health. Third, we discuss the data and present the results. Finally, we conclude by discussing how our findings contribute to understanding the intersections of the environment, education, health, and social inequality.

BACKGROUND

The Urban City as a Built and Social Environment

The environment is frequently viewed as natural, organic, and physical. However, sociologists and public health scholars illuminate built and social dimensions as well, particularly in urban areas. Cities in urban America are often made and constructed by humans. The land, air, water, and weather are in some ways dictated by built dimensions. “The built environment refers to human-made (versus natural) resources and infrastructure designed to support human activity, such as buildings, roads, parks, restaurants, grocery stores, and other amenities” (RWJF 2012). Although these resources and infrastructure are supposed to help humans flourish by having quick and easy access to green spaces for physical activity and grocery stores for healthy eating, the labor and housing markets often limit the actualization of this process. The social environment entails normative institutional arrangements such as the racial and class compositions of a neighborhood. Normative institutional arrangements are boundaries that shape social interactions and establish control over social environments (Ray and Rosow, Reference Ray and Rosow2010). Such arrangements represent taken-for-granted assumptions that are external and exist outside of individuals; they are “social, durable, layered” (Hays Reference Hays1994, p. 65), as well as constraining and enabling (Ray and Rosow, Reference Ray and Rosow2012). In this regard, normative institutional arrangements highlight the power of racial and social class composition via segregated living arrangements, such as project housing, which dictate behaviors in structured ways.

In William J. Wilson’s (Reference Wilson1996) When Work Disappears, he describes what happens to urban cities as jobs vanish. As Blacks moved north for better work opportunities and to avoid being lynched, they found work opportunities for economic advancement and upward mobility in cities including Gary, IN, St. Louis, MO, Philadelphia, PA, and Baltimore, MD. Most of these jobs were manufacturing positions dominated by men. In the 1970s as technological advances ensued, companies downsized and shipped jobs overseas. This dearth of jobs left predominately Black urban cities depleted of an economic structure to sustain the current standards of living. Simultaneously, White flight from urban spaces began taking place; and as Whites fled urban cities, so did social and cultural resources needed to properly sustain the built environment. Hence, extreme forms of poverty commenced in predominately Black areas across the United States.

Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton (1993) argue that racial segregation is the primary cause of Black poverty. They contend that the social, economic, and political segregation of Blacks are discriminatory techniques designed to trap them into urban ghettos and a vicious cycle of poverty. Part of this trapping is cutting off Blacks from access to resources that the environment (physical, built, and social) is supposed to provide. When work disappears, poverty and crime increase, and the health of residents in impoverished neighborhoods suffers.

Expanding on the work done by Massey and Denton (Reference Massey and Denton1993) and Wilson (Reference Wilson1996), Abigail Sewell (Reference Sewell and Ray2010) candidly discusses how a majority of the neighborhoods in the United States and around the world are actually ghettos and are a result of institutional forms of apartheid. Yet, there is only one group that has historically and continuously experienced ghettoization—Blacks in America. Despite some common assertions, Blacks did not develop these ghettos or voluntarily choose to live in them. Instead, through coordinated institutional acts of discrimination and uncoordinated individual acts of discrimination, Blacks were denied access to certain housing markets, thereby creating spatial segregation (Sewell Reference Sewell and Ray2010). Neighborhood associations were formed to prevent Blacks from moving into certain neighborhoods. These neighborhood associations continuously lobbied lawmakers to implement zoning restrictions to exclude Blacks. Restrictive covenants, contractual agreements signed by neighborhood tenants who agreed not to sell, rent, lease, or allow certain groups (i.e., Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, Asians) to occupy property in a particular neighborhood, were established to deny Black entry clauses into predominately White neighborhoods. Footnote 1

Since Blacks were excluded from certain neighborhoods, they were relegated to others. Contrary to the current cheap housing markets of predominately poor Black neighborhoods relative to predominately White neighborhoods, ghettos limited to Blacks historically had excessively high rent. Thus, White real estate companies and agents had an invested interest in creating more urban ghettos. Redlining ensued as real estate agents would go door to door warning Whites of the “Black invasion” so that they could increase prices and rent to needy Blacks (Massey and Denton, Reference Massey and Denton1993). Redlining is particularly detrimental to the built environment as the practice of denying or increasing the costs of essential services such as banking, insurance, health care, grocery stores, and public transportation impact health and education.

These dynamics compound on the most vulnerable citizens—poor children who are mostly Black or Hispanics. How are children supposed to focus on a standardized test when their bronchial tubes are filled with pollution, the food located near their homes is unhealthy, and the commute to and from school is tumultuous due to gang activity and/or over policing (Gilbert and Ray, 2016; Sewell Reference Sewell and Ray2010)? Nonetheless, narratives about oppositional culture and “acting white” are posited as being responsible for poor academic performance despite quantitative and qualitative research debunking these claims (Carter Reference Carter2005; Harris Reference Harris2011; Kozol Reference Kozol1991, Reference Kozol2006; Tyson Reference Tyson2011). As R. L’Heureux Lewis and Evangeleen Pattison (2010) contend, education has always been viewed as the “great equalizer.” Moreover, people think that education can solve most of the problems related to racial inequality, including those problems related to the environment. This is because most people actually believe that all schools are equal and that students are “good” and “bad” instead of schools being “good” and “bad” (Lewis and Pattison, Reference Lewis, Pattison and Ray2010; Lewis-McCoy Reference Lewis-McCoy2014).

Jonathon Kozol (Reference Kozol1991) shows that there are actually “bad” schools, and argues that school funding is the primary reason for racial differences in academic achievement. He masterfully documents the woes of inner-city schools in East St. Louis, MO, Chicago, IL, New York City, NY, Camden, NJ, Washington, D.C. and San Antonio, TX. Kozol paints a portrait of inner-city schools as dilapidated, under-funded, under-staffed, under-resourced, overcrowded, and unsanitary that is in sharp contrast to the suburban and/or county schools that typically have an abundance of resources including a low teacher-student ratio, computers, media stations, and up-to-date science equipment. These schools typically have at least twice as much funding as the urban schools described in Kozol’s study. Kozol (Reference Kozol2006) argues that schools are placed on unequal economic fields that generally fall along racial lines because of the significant inequalities that are a result of the unequal funding that public schools receive.

Establishing Environmental Equity in the City

Given these structural conditions in urban areas, some scholars have called for an increase in civic education. Harry Boyte (Reference Boyte1993) argues that civic education “enhances professionalism understood as civic craft, while it also allows students to claim and develop a larger, interactive civic identity on the public stage” (p. 764). Footnote 2 Presenting findings from data collected in 2002, Molly Andolina (2003) and her colleagues conclude that “habits formed at home, lessons learned at school, and opportunities offered by outside groups all positively influence the civic engagement of youth” (p. 275). Footnote 3 Galston (Reference Galston2001) compares traditional classroom-based civic education to service learning. Service learning combines community-based learning with classroom experiences. More recently, scholars have noted the broader benefits of informal learning environments. Learning experiences in these informal contexts are characterized as learner-motivated, interest-based, voluntary, open-ended, non-evaluative, and collaborative (Falk and Dierking, Reference Falk and Dierking2000; Griffin and Symington, Reference Griffin and Symington1997; Rennie Reference Rennie, Abell and Lederman2007). Moreover, students who have engaged in informal learning settings are more likely to view themselves as scientists as a result of participating in informal learning environments (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lewenstein, Shouse and Feder2009).

These findings regarding informal learning settings are made more important by the fact that minority and poor students are less likely to have access to and engage in activities that align with academic achievement. They are also less likely to view themselves as scientists or other professionals, such as public servants or teachers. Consequently, minority and poor students may be less likely to pursue science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) careers (Fenichel and Schweingruber, Reference Fenichel and Schweingruber2010). A report from the National Academy of Sciences notes that experiences in informal settings can improve science-learning outcomes for groups that are historically underrepresented (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lewenstein, Shouse and Feder2009). As a result, major national organizations have shown support for informal science learning opportunities as a means to improving science literacy and addressing serious environmental issues (American Association for the Advancement of Science 1993; National Research Council 1996).

School Gardens in the City

School gardens are increasingly becoming a common place for informal learning (Bell et al., Reference Bell, Lewenstein, Shouse and Feder2009; Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013). In Schools of Tomorrow, Dewey and his daughter detailed several experimental schools that incorporated active learning through nature study and working school gardens (Dewey and Dewey, Reference Dewey and Dewey1915). They concluded that school gardens incorporated the best practice pedagogy into instructional practice through participation in real-life activities. In Democracy and Education, Dewey (Reference Dewey1916) explains:

Gardening, for example, need not be taught either for the sake of preparing future gardeners, or as an agreeable way of passing time. It affords an avenue of approach to knowledge of the place farming and horticulture have had in the history of the race and which they occupy in present social organization. Carried on in an environment educationally controlled, they are means for making a study of the facts of growth, the chemistry of soil, the role of light, air, and moisture, injurious and helpful animal life, etc. There is nothing in the elementary study of botany which cannot be introduced in a vital way in connection with caring for the growth of seeds. Instead of the subject matter belonging to a peculiar study called botany, it will then belong to life, and will find, moreover, its natural correlations with the facts of soil, animal life, and human relations. As students grow mature, they will perceive problems of interest which may be pursued for the sake of discovery, independent of the original direct interest in gardening—problems connected with the germination and nutrition of plants, the reproduction of fruits, etc., thus making a transition to deliberate intellectual investigations (p. 200).

More recently, school gardens have become a popular tool for environmental education initiatives (Skelly and Zajicek, Reference Skelly and Zajicek1998; Waliczek and Zajicek, Reference Waliczek and Zajicek1999). Currently, over 3,000 school gardens are being used across the United States for educational purposes (National Gardening Association 2010). These so-called “garden-based learning” programs are found to have numerous positive effects on students. Academically, studies note that garden-based curricula improve the academic achievement of students (Blair` 2009; Dirks and Orvis, Reference Dirks and Orvis2005; Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013; Klemmer et al., Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005a, Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005b; Smith and Mostenbocker, Reference Smith and Mostenbocker2005; Williams and Dixon, Reference Williams and Scott Dixon2013). A recent synthesis of garden-based learning research showed positive impacts on direct academic outcomes with the highest positive impact on science, followed by math and language arts (Williams and Dixon, Reference Williams and Scott Dixon2013). Given these findings, the informal learning setting of school garden programs has the potential to play a role in decreasing the racial test score gap.

School garden programs also have positive effects beyond classroom academics. Research has found that they improve nutritional habits by encouraging children to eat more vegetables (Lineburger and Zajiceck, Reference Lineberger and Zajicek2000; Nanney et al., Reference Nanney, Johnson, Elliott and Haire-Joshu2006), increase students’ environmental attitudes (Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013; Skelly and Zajicek, Reference Skelly and Zajicek1998; Waliczek and Zajicek, Reference Waliczek and Zajicek1999), provide an opportunity for exercise (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Rickinson, Teamey, Morris, Young Choi, Sanders and Benefield2006), and advance social and emotional growth (Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013). In her study of second graders, Carley Fisher-Maltese (Reference Fisher-Maltese2013) found that a garden-based science curriculum focused on insects resulted in a number of affordances, including notable improvements in science learning, cross-curricular lessons in an authentic setting, a sense of school community, positive shifts in attitude toward nature, and increased collaborative work among students.

To date, however, research has yet to explore the degree to which the effects of school garden programs vary by the racial and class composition of the student body. In other words, as the extant literature points out, there is a clear need for an analysis of how informal learning environments such as school gardens vary by race and class, and how it may contribute to attenuating the achievement gap. As school gardens gain popularity across the U.S., understanding their potential impacts becomes increasingly important. Given the lack of cultural and social capital in lower-income communities, exposure to school gardens could result in larger payoffs related to academic achievement, environmental attitudes, and nutrition knowledge for students in these schools. Accordingly, we address three hypotheses. In the sections that follow, we present our hypotheses and introduce our empirical case for studying the effects of school gardens in Washington, DC.

HYPOTHESES

Hypothesis 1—School gardens are more likely to be at schools with a higher percentage of White students and in schools with a lower percentage of students on free and reduced lunch. Given research on racial disparities in school resources (Kozol Reference Kozol2006; Lewis and Pattison, Reference Lewis, Pattison and Ray2010; Lewis-McCoy Reference Lewis-McCoy2014), it stands to reason that school gardens may be more prominent in schools that are predominately White and middle class.

Hypothesis 2—The presence of school gardens is associated with higher test scores. Although most of the studies on school gardens are qualitative and normally occur in one school (Blair Reference Blair2009; Dirks and Orvis, Reference Dirks and Orvis2005; Fisher-Maltese Reference Fisher-Maltese2013; Klemmer et al., Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005a, Reference Klemmer, Waliczek and Zajicek2005b; Smith and Mostenbocker, Reference Smith and Mostenbocker2005; Williams and Dixon, Reference Williams and Scott Dixon2013), the collective research suggests that the presence of school gardens increases academic achievement due to the various dimensions of learning possibilities.

Hypothesis 3—School gardens attenuate the association between the race and class composition of students and academic achievement. Based on the fact that lower-income students as well as Black and Latino students are in schools with fewer resources, it is plausible that gaining an important resource, such as a school garden, will improve academic achievement. Thus, in line with the literature on school resources (Kozol Reference Kozol2006; Lewis and Pattison, Reference Lewis, Pattison and Ray2010; Lewis-McCoy Reference Lewis-McCoy2014), we might expect for the racial and social class achievement gap to decrease.

METHODS

In August 2010, the Healthy Schools Act of 2010 was unanimously passed by the City Council of the District of Columbia. The Act aims to “improve the health, wellness, and nutrition of the public and charter school students in the District of Columbia” (Healthy Schools Act of 2010). Building on the momentum for urban agriculture, local foods, and school gardens, the Healthy Schools Act formally provides resources to support school garden programs throughout Washington, DC that have been initiated by teachers and principals. One of the major components of the program involves the distribution of competitive grants that support the creation and maintenance of school gardens as part of the schools’ curricula and broader programs. The grant proposals are evaluated for funding based on four main criteria: project vision and implementation plan, curriculum integration plan, student and community involvement plan, and cost effectiveness of budget. In particular, reviewers (who are selected based on their knowledge of the DC school garden program and/or some experience doing work on the environment and/or education) focus on whether the proposals emphasize how students will be encouraged to make connections between the school garden, the classroom, and improved food selection and choices.

As of 2014, the program had distributed sixty-six grants throughout the District to teachers or principals who applied. Footnote 4 The grant program continues to grow and a partnership with Food Corps has provided additional support to school gardens in Washington, DC. Although DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) has conducted assessments of these gardens, Footnote 5 these reports mostly provide summaries of how many students have access to the various health initiatives in the city as well as recommendations for future years of the program. Consequently, little is known about how race and social class inequalities throughout the district impact the association between the presence of school gardens and student academic achievement. Since participation is required for all students enrolled in classes that are employing a garden-based curriculum, and school gardens are distributed throughout Washington, DC, this program provides an opportunity for examining whether the presence of school gardens in schools mediate race and class disparities in math, reading, and science test scores among students.

Data

We used DC standardized test data (DC Comprehensive Assessment System—DC CAS) to study all of the fifth grade students enrolled in the public schools in Washington, DC to examine quantitative differences between traditional and garden-based learning. Footnote 6 Fifth grade was chosen because students take the reading and math DC CAS as well as standardized science tests at the end of this year. Accordingly, the dependent variables for our analysis are the academic achievement test scores in math, reading, and science for fifth graders in Washington, DC public schools. Using the established testing typology, scores are categorized into Below Basic, Basic, Proficient, and Advanced levels. The percentage of students at each school in each category is used. Since proficient is considered average, we primary focus on this category. Math and reading test scores come from the 2012–2013 school year, while the science test scores come from the 2013–2014 school year. For math and reading, we have data on eighty-three public schools with fifth grade. For science, we have data on seventy-two schools. There were nine schools with missing data and two schools that had sample sizes of less than ten students and therefore did not report any data.

The presence of a garden at a school served as the main independent variable. Footnote 7 Based on the total number of test takers in each school, the percentage of White, Black, Hispanic, and free or reduced lunch students were provided by DC OSSE. Since we had the number of students by race and free or reduced lunch, we were able to then compute the number and percentage of students who were not White, Black, or Hispanic. We were also able to verify the percentages provided for each group. Accordingly, other independent variables include proportion of Blacks in the school and proportion of Hispanics in the school. We also include the proportion of students on free or reduced lunch, which captures the household income of the students. For these independent variables, the 2012–2013 percentages are used for math and reading, while the 2013–2014 percentages are used for science.

Analysis

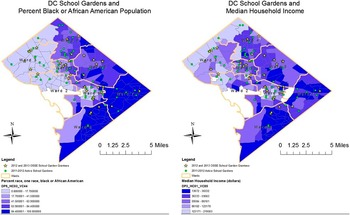

First, we plot the location of all school gardens throughout DC through the 2012–2013 academic year. Using the 2007–2011 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates by the U.S. Census Footnote 8 and street addresses of schools with gardens, we map school gardens according to the percent of Black residents and median household income in the neighborhood. It should be noted that Washington, DC has a school lottery where parents or guardians rank schools for their children. This means that students may not attend their neighborhood school. Thus, assessing the race and class composition of the student body becomes more central to examining academic achievement than neighborhood characteristics in Washington, DC. Still, as our analysis will show, there is a strong link between school and neighborhood resources. School gardens are one of the few resources that neighborhood residents can partake in without much red tape.

Second, we show the number and percentage of gardens in DC public schools with fifth graders. Third, we assess student access to school gardens according to their race and income. Next, we disaggregate math, reading, and science test scores by the presence of school gardens. Finally, we present a series of regression models to examine the association between having a garden in a school and math, reading, and science test scores. These models control for the proportion of Black, Hispanic, and free or reduced lunch students in the school. They also examine whether a variable for the presence of a school garden attenuates the relationship between the racial and class composition of students and test scores.

RESULTS

Figure 1 shows the distribution of active school gardens for all grade levels in Washington, DC through the 2012–2013 academic year. The stars indicate schools that were supported through grants from DC OSSE, while the green dots show active school gardens. The map on the left shows the school gardens by the percentage of Black residents in the neighborhood and the map on the right shows the school gardens by median household income in the neighborhood. As the maps illustrate, Washington, DC is highly segregated by race and income. At the same time, school gardens seem to be relatively distributed throughout the city’s eight Wards. These characteristics make Washington, DC an ideal location to conduct a study on the association between school gardens and the academic achievement gap. We now focus specifically on school gardens for fifth grade.

Fig. 1. DC Schools by Percent Black Population and Median Household Income of Neighborhoods

Table 1 shows the distribution of schools according to school garden status for the 2012–2013 academic year. Of the eighty-three public schools with fifth grade, 48% of them have school gardens. Fifteen of the forty school garden schools were awarded grants from DC OSSE. Table 2 shows access to school gardens by the race and income composition of the students in the schools. 70% of students in DC public schools are Black, compared to 15% Hispanic, and 11% White. 80% of students in DC public schools are on free or reduced lunch. Black students and students on free or reduced lunch are the groups that are overrepresented in schools that do not have school gardens. In fact, 91% of students in schools without gardens, compared to 54% of students in schools with gardens, are Black. While only 1% of students in schools without gardens is White, 18% of students in schools with gardens are White. Hispanics follow a similar pattern to Whites. They represent 22% of students in schools with gardens, but only 7% of students in schools without gardens. Students on free and reduced lunch follow a similar pattern as Blacks. Students on free or reduced lunch represent 95% of students at schools without gardens. These patterns document that the presence of school gardens is linked to race and class composition. Supporting Hypothesis 1, school gardens are more likely to be in schools with a higher percentage of White students and in schools with a lower percentage of students on free and reduced lunch.

Table 1. Gardens in DC Public Schools with 5th Graders, 2012–2013

Table 2. Student Access to School Gardens by Proportion of Racial Groups and Class Composition in Schools, 2012–2013

Table 3 shows fifth grade test scores by the presence of school gardens. Supporting Hypothesis 2, for math, reading, and science, students in schools with gardens are more likely to score in the proficient or advanced categories, compared to students in schools without gardens. For math, 22% of students in schools without gardens score in the below basic category compared to 11% of students in schools with gardens. 21% of Black students, compared to 1% of White students and 5% of Hispanic students, score below basic in math. On the other end of the scoring continuum, 92% of White students, compared to 62% of Hispanic students, and 38% of Black students, score in the proficient or advanced categories. 18% of students on free and reduced lunch score in the below basic category. Similar to Blacks, 41% of students on free and reduced lunch score in the proficient or advanced categories.

Table 3. 5th Grade Test Scores by Presence of School Garden

For reading, 61% of students in schools with gardens score proficient or advanced, compared to 38% of students in schools without gardens. A similar percentage (16% and 15%) of Black and free or reduced lunch students score below the basic level in reading. Only 1% of White and 8% of Hispanic students score below basic in reading. For science, 47% of students in schools with gardens score proficient or advanced, compared to 21% of students in schools without gardens. Therefore, nearly 80% of students in schools without gardens score at the basic or below basic levels in science.

Since it is clear that students in schools with gardens have higher math, reading, and science test scores, we now examine Hypothesis 3 to determine whether the presence of gardens in schools attenuates the relationship between the race and class composition of students and academic achievement. Tables 4–6 show regression models of the association between the presence of school gardens and academic achievement. Table 4 shows models for math. Model 1 shows that the presence of gardens is associated with students having higher math scores than students in non-garden schools (B= 0.075; p<.05). Controlling for the percentage of students on free or reduced lunch, shows a similar pattern, though the magnitude of the association reduces (B= 0.063; p<.10). However, controlling for the proportion of Black and Hispanic students in the school, the association between school gardens and math scores become non-significant (B= 0.044; p>.10). Model 4, which controls for race and income composition of students in schools, shows a similar pattern to Model 3.

Table 4. Regressions of the Association between School Gardens and Math Proficiency among 5th Graders in DC Public Schools, 2012–2013

***p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1; Standard errors in parentheses.

Table 5. Regressions of the Association between School Gardens and Reading Proficiency among 5th Graders in DC Public Schools, 2012–2013

*** p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1; Standard errors in parentheses.

Table 6. Regressions of the Association between School Gardens and Science Proficiency among 5th Graders in DC Public Schools, 2013–2014

*** p<0.01, **p<0.05, *p<0.1; Standard errors in parentheses.

Table 5 shows the models for reading. In Model 1, the association between the presence of a garden in schools is significant and positive (B= 0.186; p<.01). Controlling for the percentage of students on free or reduced lunch (B= -0.152; p<.05), the presence of school gardens is still associated with higher reading scores (B= 0.152; p<.01). Model 3 controls for race in schools. Although the proportion of Blacks in the school is associated with lower reading scores (B= -0.216; p<.05), the presence of school gardens still has a significant and positive association with reading scores (B= 0.138; p<.01). Model 4, which controls for race and income composition, still shows that the presence of gardens is associated with higher reading test scores (B= 0.135; p<.01). The proportion of Blacks in the school moves to non-significance.

Table 6 shows models for science. Model 1 shows a significant and positive association between schools with gardens and science test scores (B= 0.167; p<.01). Controlling for free or reduced lunch (B= -0.319; p<.01), the association between schools with gardens and science test scores (B= 0.086; p<.05) is similar to Model 1. The pattern persists in Model 3, though the associations between the proportion of Black (B= -0.405; p<.01) and Hispanic (B= -0.354; p<.01) students in the school is associated with a decrease in science test scores. Model 4, which controls for race and income composition, shows that the presence of gardens in schools is still positively associated with higher science test scores (B= 0.072; p<.10), though the magnitude is reduced. Including free or reduced lunch (B= -0.272; p<05) shifts the association between the proportion of Black and Hispanic students in the school and academic achievement to non-significance.

Collectively, Tables 4–6 demonstrate that school gardens are significantly associated with higher math, reading, and science test scores. However, school gardens do not necessarily attenuate the association between the race and class composition of students and academic achievement. Rather, the proportion of Black students in a school is positively correlated with the percentage of students on free or reduced lunch in that school. Altogether, there is little support for Hypothesis 3, though the significant and positive association between the presence of school gardens and test scores persists even when controlling for the race and income composition of students for reading and science.

CONCLUSION

This paper examined whether creating more environmental equity in schools (as measured by the presence of school gardens) improves academic achievement. Using data from the DC CAS standardized tests for schools with fifth grade, we found that Black and lower-income students are more likely than White and Hispanic students to underperform on math, reading, and science tests. Students who attend schools with gardens are more likely to perform at the proficient or advanced levels on standardized tests. Correspondingly, White and Hispanic students as well as students who attend schools with a lower percentage of students on free or reduced lunch are more likely to attend schools with a garden-learning program. There is a correlation between predominately Black schools and schools with a high percentage of students on free or reduced lunch.

A central part of our analysis was determining whether there is a significant and positive association between the presence of school gardens in schools and test scores. For math, reading, and science test scores, we found support for this proposition. We also found that for reading and science scores, the positive and significant association persists even when controlling for the race and class composition of the students. For math scores, the significance of school gardens persists even when controlling for the income of students. The significance of school gardens, however, fades with the inclusion of the race composition of students. Additionally, the presence of school gardens does not attenuate the association of race and income composition and reading and science test scores. Yet, for reading, including the race and income of students in the same models reduce both to non-significance. For science, income composition attenuates racial composition.

Our study contributes to understanding the ways that learning in a school garden mediates race and class inequality in academic achievement. Our findings on the importance of the presence of school gardens provide credence to structural resources as gateways to reduce the achievement gap (Kozol Reference Kozol1991, Reference Kozol2006; Lewis-McCoy Reference Lewis-McCoy2014). Our research also contributes to better understanding how best to engage Black and lower-income students to view science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) as possible career paths. Furthermore, our findings also speak to decision makers who want to engage more diverse populations in civic and environmental activities, healthy eating, and physical activity.

In addition to addressing academic outcomes, school gardens become potential gateways for thinking of ways to spur racial/ethnic and lower-income residents to engage in environmental and civic activities locally. A number of studies highlight that some minorities participate in environmental activism through the environmental justice movement (Alkon and Agyeman, Reference Alkon and Agyeman2011; Boone and Fragkias, Reference Boone and Fragkias2013; Bullard Reference Bullard1990; Pellow and Brulle, Reference Pellow and Brulle2005; Taylor Reference Taylor2000). Environmental justice addresses inequities where people live, work, and play (Bullard and Johnson, Reference Bullard and Johnson2000; Taylor Reference Taylor2000). Issues related to water, heat/air, clean and safe land, and food become central to residents in urban, low-income neighborhoods.

Accordingly, our findings pose some additional important questions concerning the role that the built environment plays in educational and health outcomes. While we know that school gardens matter, how exactly do they matter? Are school gardens simply an additional school resource or do they have some unique qualities that are important for academic achievement, healthy eating, and physical activity? Do students learning in a garden-based program influence the food purchases of their families? Future research can explore these possibilities by conducting experimental studies with students and their families before and after the implementation of a garden-based curriculum in schools.

In sum, informal learning settings, such as school gardens, provide an intriguing case for documenting the importance of creating and sustaining environmental equity. Although school gardens are created by schools, and not local residents, and require the participation of students in classes that choose to engage in a garden-based curriculum, this type of hands-on learning has the potential to provide a gateway to other types of environmental stewardship and civic participation. In addition to improving academic achievement, school gardens may enhance healthy eating and increase both physical activity and civic participation among students and their families.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank Sam Ullery and members of the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education staff for access to these data and information regarding the school garden grant program in Washington, DC (for more details see www.osse.dc.gov). We also thank Joseph Waggle and Moriah Willow for assistance with data collection and analysis. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the White House to the Let’s Move Campaign and the 2016 American Education Research Association annual conference in Washington, DC.