Introduction

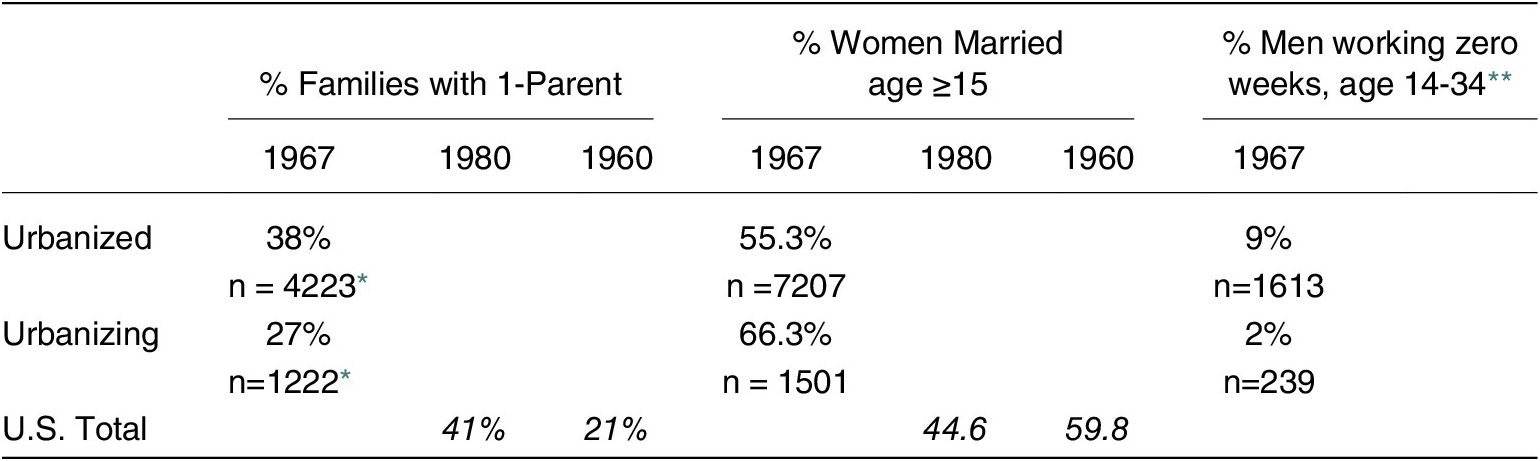

Between 1880 and 1960, the proportion of Black children in single-parent families exhibited remarkable stability hovering in a narrow band around twenty percent. Abruptly, this demographic equilibrium shattered between 1960 and 1980 as the proportion doubled then continued its sharp rise to a new demographic equilibrium just above fifty percent about 1990 (see Figure 1). This paper reinterprets the time trend introducing an economic behavioral model of Black agency mediated through the structure of race relations. Distinct discrimination experiences in urban versus rural settings structured distinct child socializations (hence agencies) and family formations. Historically, rates of mother-only families (about 40% for urban socialized and 10% for rural, respectively) were stable. The relatively low pre-1960 demographic equilibrium was an average dominated by rural socialized Blacks’ population majority. Mass urbanization during 1940–1970 ensured that by 1970 most Blacks of procreation age had been socialized in urban settings. The 1960–1980 doubling (21% to 41%) of Black children in one-parent families emerged as urbanization converged Blacks toward urban socialized Blacks’ historically high adaptation to urban forms of racism. Post-1960 events such as welfare liberalization and deindustrialization exacerbated conditions but were not fundamental causes.

Fig. 1. Percentage of Children Living with One Parent, 1880–2006

Data for 1880, 1910, 1940, 1960, 1980 are children ages 0-14 from Ruggles (Reference Ruggles1994) (Table 2); 1900 children ages 0-15 from Gordon and McClanahan (Reference Gordon and McLanahan1991) (Table 7); 1970, 1990, 2000, 2006 children ages 0-18 from published U.S. Census reports.

The hypothesis is tested by analyzing 5445 Black and 10,545 White rural and urban socialized households with children in the Census Bureau’s 1966–1967 Survey of Economic Opportunity (SEO). I find that already thirty-eight percent of urban socialized Black household heads were mother only, eleven percentage points greater than rural socialized household heads living in an urban area. Logistic regression estimates of single parenthood probabilities confirm the summary statistics and discredit alternative interpretations of the data. Childhood location effects are equal in Northern and Southern cities (findings are not interregional migrant effects), and zero among the placebo group (Whites), showing findings are a pure race effect. Qualitative evidence (ethnography, historical, autobiography) reinforce the theory that rural-urban child socialization differences structurated (Giddens Reference Giddens1973) significant differences in Black agencies and social outcomes historically.

This article is organized as follows. The next section reviews related literature setting out the issues and existing explanations and clarifying this paper’s contribution. Next, I exposit an economic behavioral theory linking Black choices of identity and agencies to distinct rural/urban child socialization experiences. The behavioral explanation hypothesizes that childhood socialization processes mediate individuals’ drive for self-verification and resulting choices of identity/agency. Distinct rural and urban socialization processes structurated distinct Black behaviors creating different family patterns throughout U.S. history. Evidence for these theoretical assertions is provided in three steps. First, applying logistic regression techniques to data from the 1966–1967 SEO, a direct statistical test of the theory confirms that among Blacks living in urban areas, those socialized in urban settings had greater rates of one-parent families than those socialized in rural settings. Moreover, the research design eliminates alternative interpretations of the data. Next, I examine how child socialization differed in the two settings. I identify specific ecological features that led forward-looking urban adolescents seeking self-verification to adopt agencies of resistance, but incentivized rural adolescents to conform to White supremacy. Using methods akin to economic anthropology, I employ historical, autobiographical, and ethnographical sources to identify rural/urban socialization differences across genders. The final section summarizes additional evidence supporting the hypothesis that “cultural” practices observed in low-income urban communities today derive from agencies of resistance structurated by urban socialization patterns rooted deep into the nineteenth century.

Literature Review

Two theoretical traditions (often framed as competitors) dominate discussions of Black American’s high poverty rate and family structure: culture of poverty and structural barriers. Identifying social structure as the primordial cause, this article contributes to a more recent literature arguing culture and structure determine behavior in concert (Small et al., Reference Small, Harding and Lamont2010). I argue behavioral responses to social structure can become part of a people’s cultural repertoire, but structure is primordial.

Culture of Poverty

Cultural explanations posit the existence of a Black subculture whose dysfunctional values underlay behaviors that perpetuate poverty (Lewis Reference Lewis1966; Moynihan Reference Moynihan1965). Some of Daniel P. Moynihan’s post-1970 heirs explain Black mother-only families and correlates such as high rates of joblessness and poverty in terms of a cultural proclivity toward dependence on public welfare (Lemann Reference Lemann1986; Mead Reference Mead2020; Murray Reference Murray1984). This paper refutes these cultural explanations. More recent discussions of the culture of poverty argue that Oscar Lewis’ work has been misinterpreted and that he regarded the values and dysfunctional behaviors he observed among poor people as unfortunate coping mechanisms developed in response to disadvantaged desolate lives (Hill Reference Hill2002; Kurtz Reference Kurtz2014). The idea that many poor people’s behaviors can be framed as coping behaviors provides a bridge between cultural and structural explanations, although I theorize structure forges culture.

Structural Barriers to Opportunity

Structural arguments point to systemic discrimination and/or socioeconomic transformations such as deindustrialization and the disappearance of working-class jobs paying living wages as primary forces in creating male joblessness and mother-only families (Brady and Wallace, Reference Brady and Wallace2001; Kasarda Reference Kasarda1989; Wilson Reference Wilson1987, Reference Wilson1996). Promising lines of analysis during the twenty-first century focus on the idea that many poor people’s behaviors are coping strategies to deal with structural barriers such as a lack of decent jobs. Various authors argue these explanations need to show how structural conditions interact with individual situations to produce observed behaviors (Bourgois Reference Bourgois2001; Small et al., Reference Small, Harding and Lamont2010).

The interpretation offered here aligns with the structure-culture interaction view positing social structure (economic conditions) explain many kinds of behaviors labeled culture. Critics rightly argue that proponents of the structural argument have not shown precisely how social structure (more precisely, changes in social structure) alter behavior and culture.

Part of the difficulty entailed in disentangling the complex relationships between structure, culture, and behavior has been methodological. Understanding the origins of complex behavioral outcomes such as high rates of joblessness and mother-only families requires the kind of serious commitment to interdisciplinary methods practiced in Black Studies scholars’ ongoing attempts to marry historical, humanities, and social science methods. Understanding how social structure created and sustains observed group outcomes that so frequently situate Blacks in the worst conditions is not possible using a single disciplinary approach. To illustrate better both the theoretical elision to which I refer and how an interdisciplinary approach melding historical and social science methods offers a way out of the difficulty, consider an important paper by demographer Steve Ruggles (Reference Ruggles1994) who concludes (erroneously, I believe) that cultural explanations of differences in Black-White family structures appear as persuasive as economic-structural ones.

The reason driving Ruggles’ conclusion derives from what he calls a “puzzling” finding: during 1880, among Blacks, those “who faced the worst conditions—illiteracy and residence in the poorest districts—had the highest odds of residing in a two-parent family” (1994, p. 148). The opposite was true of Whites. Ruggles has uncovered a serious weakness in the structural argument. Structural explanations must be more subtle than claiming economic stress causes single parenthood. The move from structure to effect remains too much a black box. The way out of the box requires directly disentangling the “puzzling” finding itself, and the disentangling requires bringing to bear methods of economic anthropology, social psychology, and quantitative analysis upon distinct historical settings.

The areas generating Ruggles’ puzzling finding for 1880 were Black Belt plantation districts with low literacy and high poverty. These economic enclaves also happened to be where Black children of 1880 were most likely to live in two-parent families. However, poverty per se had less to do with their family structure than did the functional role of the two-parent family in the plantation system. By 1880, the economic organization of Southern agriculture was founded in a symbiotic relationship bonding the plantation system to two-parent household production relations that had little to do with culture (Jaynes Reference Jaynes1986; Ransom and Sutch, Reference Ransom and Sutch1978). No functional relationship bound together sub-living wage husband/wife households and jobs in urban settings where high rates of mother-only Black families resided in 1880. The absence of such ties and urban economies’ deleterious effects on Black families, not Black culture, are the major structural forces explaining urban Blacks’ higher rate of one-parent families in 1880 or 1980.

Regardless of the theoretical position taken with respect to structure or culture, virtually all social science research on Black families has focused on post-1960 events to explain the trend in Figure 1. This research strategy seems warranted given that time-path. However, the emphasis on post-1960 explanations is misplaced. Leading explanations such as post-1960s deindustrialization or social policy disincentives to marry due to welfare state expansion likely exacerbated the changes and have a role in sustaining them at present. However, such explanations cannot account for the high rates of single-parent families that already characterized city-raised Blacks’ family structure during the mid-nineteenth century and likely even earlier (see below).

S. L. Engerman (Reference Engerman1977), Frank F. Furstenburg, et al. (Reference Furstenburg, Hershberg and Modell1975), and Eugene D. Genovese (Reference Genovese1974) dispute the post-1960 framing. Each hypothesized high rates of Black mother-only families were best explained by discrimination in Northern cities. Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton (Reference Massey and Denton1993), linking structural and cultural effects, argued residential segregation and discrimination after the Black Northern migration during WWI created an “oppositional culture” among poor Blacks characterized by poor school performance, denigration of mainstream employment, and raising children outside of marriage (p. 168). This paper differs in several significant respects. First, my conceptualization covers urbanization’s effects South and North, it is not a Northern migration argument; second, it includes large and small cities; third, I date the structural-behavioral interactions responsible for the behavioral changes well before the growth of large segregated Black ghettos created by early twentieth-century migration; fourth, although segregation is important, I identify the major causal variable as labor market discrimination; and fifth, my behavioral-economic formulation interprets agency outcomes as adaptive resistance to historical racist structures, not oppositional culture grounded in disdain for acting White—a distinction worth making.

I also emphasize that this article does not contest the important archive of research examining the social and economic motivations driving marriage, child-rearing, and cohabitation decisions in the contemporary settings of recent decades. That literature is quite consistent with this paper’s explication of the nineteenth century origins of late-twentieth century Black family structure (see below).

Conceptualizing the Issue

As applied here, behavioral economics explains behavior by adducing the economic consequences of assuming a theoretical construct of social psychology (here self-verification) underpins individual choices. Self-verification refers to a basic human need to receive social affirmation one’s core beliefs about oneself (one’s identities) are true (Giecas and Schwalbe, Reference Giecas and Schwalbe1983; Stets and Burke, Reference Stets and Burke2000). Self-verification underpins a fundamental proposition of social psychology that human beings avoid people and institutions that view them in ways they choose not to see themselves. Hence, one response to a failure to achieve self-verification in some important social realm (and the one this article focuses on) is defensive—avoid those settings and social roles jeopardizing one’s ability to self-verify a positive sense of self (Goffman Reference Goffman1973; Kelvin and Jarett, Reference Kelvin and Jarrett1985). An alternative response (not discussed in this paper) is offensive—intensely engage those settings and social roles to alter how one is perceived. Combining these behavioral strategies with an economic anthropological description of crucial differences in the economic forces driving children’s socialization in rural versus urban Black enclaves provides a powerful means of explaining important behavioral choices such as labor market participation and family formation among Black men and women trying to preserve their self-worth by not conforming to family and economic formations that undermine their self-esteem.

The rural Southern economy was structured on the employment of husband-wife families with access to a farm tenancy ladder whose highest rungs appeared accessible to Blacks. A key element in the socialization of Black children was their high exposure to adult role-models seeking self-verification by striving to climb this tenure ladder—a life goal requiring they conform to behavioral norms based in White supremacist race relations. Failure to self-verify a positive self-image by achieving land ownership or rental tenancy was common but occurred during mature adulthood when the likelihood of adopting countercultural agencies was greatly mitigated.

Urban job structures separated men and women into distinct employment niches each encumbered by racially stratified occupational patterns blocking Blacks’ access to better jobs. Urban Black children (North and South) were exposed to large numbers of role-models socially alienated by urban job ceilings and truculently refusing to acquiesce to White supremacy by avoiding mainstream institutions. Urban children were at great risk of projecting failure to self-verify an acceptable social identity. The developmental outcome was early adoption of counterculture agencies of resistance leading to a polarized choice dependent on children’s access to resources: either seek self-verification elsewhere by avoiding institutions such as schools, labor markets, and marriage (causing high rates of official joblessness and single-parent families), or (attempting to alter one’s reception in such institutions) intensely engage them ultimately leading to civil rights activism.

The origins of the high rate of mother-only Black families resided in the social structure of towns and cities where Black children had always been socialized into agencies that evolved into coping responses to an employment structure that undermined husband-wife families. The sharp jump in mother-only families after 1960 was an inevitable consequence of the Great Urbanization of Black America. Black rural-to-urban migrants (overwhelmingly two-parent) adapted to cities relatively well. The reformation of household structure occurred among city-raised second generations who inherited cultural models of identity and agency adapted to over a century of urban racism.

Data and Methods

The conceptual framework implies that at any time prior to about 1970, it is crucial to divide the Black population into three distinct demographic constructs: the rural, the urbanizing, and the urbanized. The latter two categories composed the nation’s urban Black population: the urbanized being those Blacks whose childhood socialization occurred in some urban area, and the urbanizing being rural-to-urban migrants whose childhood socialization occurred in a rural area. The rural population is all Blacks living in rural areas. I hypothesize, throughout the period ranging from the nineteenth to the late mid-twentieth centuries, the proportions of Black children living in single-parent families were stable at approximately 40% for the urbanized and 10% for rural Blacks; urbanizing Blacks’ proportion was intermediate.

The aggregated census data in the top curve of Figure 1 represents an average of the three subpopulations. Aggregating the Black population at any time before approximately 1975 camouflages the disparate behaviors of the different subpopulations whose distinct behaviors with respect to family structure underlay the average trend. During 1900 only 15% of Blacks were urban, and most were urbanizing. The Great Urbanization of 1910–1920 increased Blacks’ urban population to 28%. However, urban Blacks remained highly urbanizing, and the census average concealed the family behavior of the urbanized whose behaviors are most relevant for predicting post-1960 family structure. Urbanization 1940–1970 made Blacks 80% urban, taking the once overwhelmingly rural population toward an overwhelmingly urbanized one. The census average converged to a new demographic equilibrium reflecting urbanized Blacks’ unchanging behavioral adaptations to urban discrimination.

The demographic transformation ensured measures of social alienation among Blacks increased significantly after 1960. The hypothesis is amenable to empirical testing using data from the SEO. The Office of Economic Opportunity (part of President Johnson’s war on poverty) directed the Census Bureau to assess nationwide the extent to which the War on Poverty was affecting economic well-being. The SEO survey completed interviews with about 30,000 households in 1966 and again in 1967. It sampled metropolitan areas throughout the nation oversampling central cities, thus including enough Blacks to draw credible statistical inferences.

Before describing my research design, it is useful to discuss possible biases in the sample descriptives shaped by the questions asked and the reasons for asking them. The variables I describe that could potentially contain measurement error beyond those usually contained in census surveys are race, marital status, and rural versus urban location of household heads during childhood.

While racial/ethnic identity is a complex issue, Census Bureau procedures during the mid-1960s did not provide respondents the array of choices complicating self-identity and street race that have been used during recent decades (Lopez and Hogan, Reference Lopez and Hogan2021). It seems unlikely SEO data present significant issues classifying Blacks and Whites. Marital status, however, requires discussion. The data assigns a household head one marital status among six classifications: married-spouse-present, married-spouse-absent, married-separated, divorced, widowed, and never-married. Classifications into these cells by self-reporting respondents could be subject to misreporting due to stigma of some designations or avoidance of financial punishment due to violations of man-in-the-house type rules that could reduce public assistance. Since W. E. B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1899), researchers have noted a tendency for urban Black mothers to over-report being widows or divorced. With respect to the stigma motivation, respondents intentionally misreporting their marital status only matters if they report the first classifications incorrectly. There is no strong reason to believe there would be an appreciable bias in this regard between urbanized and urbanizing adults. However, public assistance eligibility rules penalizing cohabitation and relations with men outside the home present possible sources of bias in the census tabulations. At the time, some nineteen states and Washington, DC had regulations denying public assistance to children with an unmarried or separated mother in a relationship (even a tenuous one) with a man (Goldsmith Jr. Reference Goldsmith1968). Women on public assistance would have an incentive to conceal such relationships and in cases where a husband or partner’s income support was less reliable than public assistance there were incentives to separate (Ladner Reference Ladner1971; Rainwater Reference Rainwater1970). Since households with an urbanized head were more likely receiving public assistance (see below), public welfare may have had a role in increasing tabulated single parenthood. However, even those who make this argument claim the significant effects were after 1967 (Murray Reference Murray1984).

For my purposes, the most relevant residential question (where a person resided at age sixteen) was coded rural or urban. This location could be North or South. I use urban and rural residence at age sixteen to index urban and rural childhood socialization, respectively. The data present two potential sources of bias. It is not possible to ascertain exactly when a respondent self-reporting urban residency at age sixteen arrived. Many respondents labeled urbanized in the data could have migrated shortly before their sixteenth birthday. These respondents should properly be coded urbanizing. If my hypothesis is true, their presence biases any measured difference in urbanized/urbanizing behaviors downwards. Analogously, respondents coded urbanizing because they report living in a rural setting at age sixteen could have been socialized in an urban setting but happened to live in a rural area at age sixteen. They also bias urbanized/urbanizing differences downward. Given the massive rural-to-urban movement of Blacks during decades preceding the SEO, the proportion of respondents miscoded urbanized should vastly exceed the proportion miscoded urbanizing, an inference reinforced by the fact all respondents are residing in urban areas.

A second source of downward bias against my hypothesis is that the Census Bureau’s definitions of rural and urban are primarily based on population size, a simplification urbanologists have long considered inferior to focusing on population density, the organization of schools, and other factors (Wirth Reference Wirth1938). Large numbers of individuals coded urbanizing in the SEO would ideally be coded urbanized. Individuals living in a jurisdiction that from the perspective of the theory should be urban but is coded by the census as rural (e.g., an unincorporated jurisdiction with a population below 2500 but whose major industry is not farming) also biases downward urbanized/urbanizing differences by inflating measures of alienation among the urbanizing. I conclude any estimates provide lower bounds on the size of group differentials and alienation among the urbanized.

Statistical Evidence: Testing the Theory

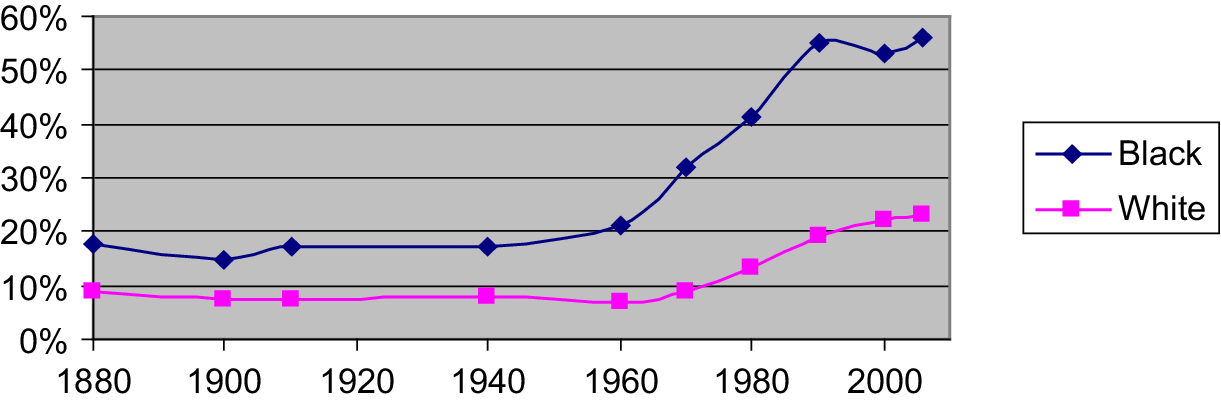

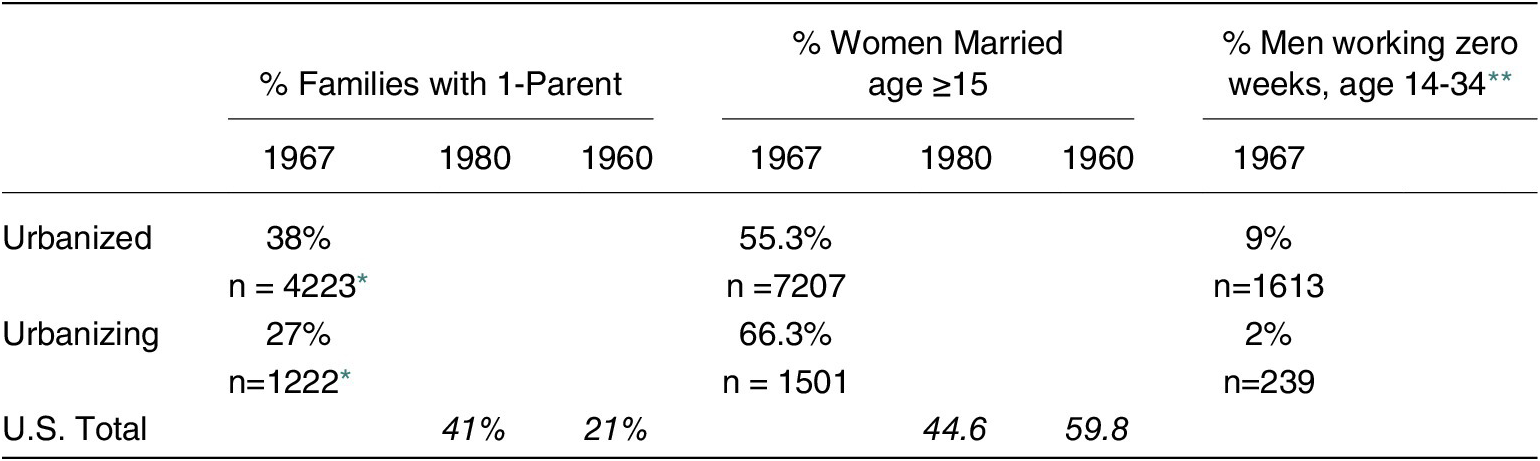

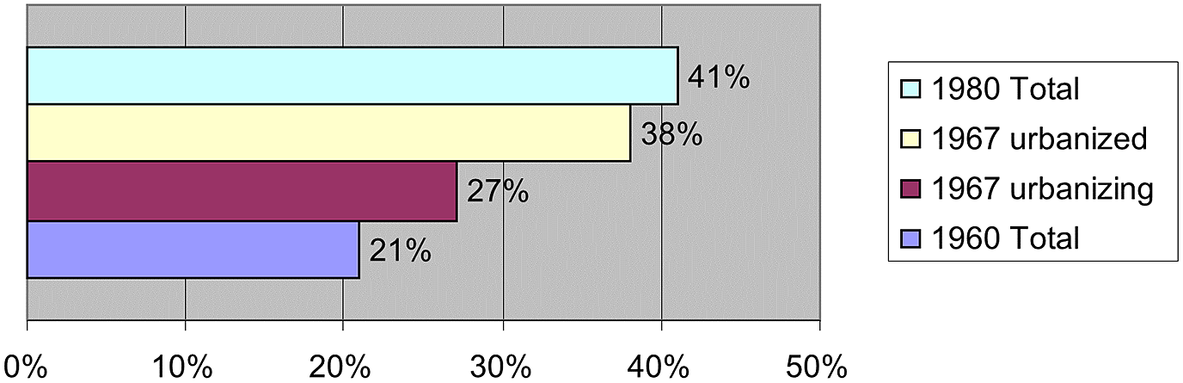

Table 1 and Figure 2 display summary statistics describing various behaviors of urbanized and urbanizing Blacks living in Northern and Southern cities during the SEO. North refers to areas not in the South. First note, a crucial finding; amid the rapidly expanding U.S. economy of the mid-1960s, one in eleven urbanized Black males—fourteen to thirty-four years of age, not in school—reported no time working or looking for work; the comparable number for same-age urbanizing Black males was only one in fifty. Among urbanized Black women ages fifteen and above, 55% were married and living with spouse compared to 66% of same-age urbanizing Black women. Despite higher average educational attainment among the urbanized, children living in families with an urbanized Black head were more likely in poverty than were children in families with an urbanizing head, 47% and 39% respectively. These counterintuitive findings make sense if one assumes my hypothesis. Predictive of the family arrangements of children in 1980, 38% and 27% respectively, of families with urbanized and urbanizing heads were single-parent (see Table 1). Importantly, urbanized/urbanizing differences were not regional. Differences in children’s living arrangements exhibited similar patterns in cities as diverse as Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, still a “Southern” city during the 1960s.

Table 1. Indices of Social Alienation among Urbanized and Urbanizing African Americans

Source: Data calculated from U.S. Bureau of the Census, SEO, 1967. Marital Status of the Population 15 Years Old and Over by Sex and Race: 1950 to Present, MS-1 (www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms1.xls).

* refers to number of families in sample.

** refers to men not in school. Urbanized and urbanizing families and persons reside in urban areas; U.S. totals refer to nationwide populations.

Fig. 2. Percentage of Black Children Living in Single Parent Families

The descriptive statistics provide preliminary evidence for the hypothesis that urban socialization was a significant determinant of Blacks’ alienation from social institutions. However, absent appropriate tests confirming the group differences are statistically significant and cannot be accounted for by reasonable alternative explanations, these findings are not definitive. More rigorous tests use logistic regression models to assess whether (after controlling for the effects of race, region, and migrant status per se) parent’s socialization location exerted a significant effect on the probabilities a family with children is two-parent or in poverty.

Competing Explanations: Northern Cultural Deficit Model and Migrant Selectivity

An alternative explanation of the data in Table 1 is that the urbanized/urbanizing differences are merely capturing differences between native-born Northerners and Southern migrants to the North. Since the 1970s, several studies found statistically significant differences in social status indices of Northern and Southern-born Blacks living in Northern cities. These studies overturned popular beliefs among the public and social scientists alike that Southern migrants to Northern cities were responsible for increases in these cities’ Black unemployment, poverty, and welfare rolls. Research showed Southern migrants to Northern cities outperformed native-born Northern Blacks in virtually all indices of social status except educational attainment, an exception making the other findings even more counterintuitive (Lieberson and Wilkinson, Reference Lieberson and Wilkinson1976; Long Reference Long1974; Tolnay Reference Tolnay1997, Reference Tolnay1998; Weiss and Williamson, Reference Weiss and Williamson1972).

The counterintuitive findings were explained with two primary arguments. The Northern deficit model argued Northern-born Blacks possessed attitudinal handicaps or cultural pathologies that ill-equipped them to compete with Southern-born Blacks, who, for some unexplained reason, did not have these handicaps. The migrant selection hypothesis argued Black Southerners living in the North (like many migrant populations) were a selected population. My statistical model must provide evidence that urban/rural socialization effects explain the data better than do broad regional effects or migrant selectivity.

Consider the regional explanation hypothesizing Northern-born and Southern-born differences. If the North-South differences in Northern cities derived from regional differences, socialization location as specified in my theory should hold no explanatory power for behavioral outcomes among Blacks living in the urban South. Alternatively, if rural versus urban socialization location is the determinative causal variable explaining family formation patterns and poverty, differences in the behaviors of urbanized and urbanizing Blacks should be significant within Northern and Southern cities. Upping the ante, a finding that the urbanized/urbanizing difference is equal in the South and North would imply a powerful structural-behavioral nexus providing especially strong evidence for the theory.

Secondly, the regression model must demonstrate urbanized/urbanizing behavioral differences are not due to migrant selectivity (e.g., rural Blacks migrating to cities were not selected on some unobserved trait that increased their probability of maintaining two-parent families). Because the urbanized/urbanizing distinction is inherently a comparison of non-migrants and migrants, this second task appears daunting. However, I dismiss the migrant selectivity explanation’s probative power in two ways. First, there is considerable independent evidence that the massive rural-to-urban migration of the mid-twentieth century, which rested on a strong push factor due to mechanization of Southern agriculture after 1940, was not selective with respect to economic characteristics of the rural population (Boustan Reference Boustan2016; Day Reference Day1967; Whatley Reference Whatley1987). Secondly, the data allow such a test. To borrow a term from Anthony Giddens (Reference Giddens1973), I am expositing a theory grounded in the “structuration” of norms of behavior among a disadvantaged minority subordinated within a social structure’s racialized class-gender relations (p. 112). Nothing in the theory implies urbanized/urbanizing behavioral differences should exist among the superordinate group, Whites. Hence, the theory implies urbanized Whites should not exhibit signs of social alienation in the North or South. Using Whites as a placebo group tests if socialization location effects found for Blacks are pure race effects, and not spurious correlations due to higher motivation to succeed among the migrants regardless of race. Behavioral differences between urbanized and urbanizing Whites should display different patterns than those among Blacks. The strongest hypothesis predicts socialization location has no effect on family formation among Whites, discrediting the hypothesis that there is a pure migrant selectivity effect producing the differences among Blacks.

Regression Model

The regression framework tests my hypothesis against alternative explanations of the descriptive findings receiving support in social science research. I estimated the following model.

Where, P(e|

![]() $ {X}_i $

) is the probability some event e is true and

$ {X}_i $

) is the probability some event e is true and

![]() $ {X}_i $

is a vector composed of the following components:

$ {X}_i $

is a vector composed of the following components:

![]() $ {s}_i $

is a binary variable indicating the ith observation’s socialization location (urban or rural);

$ {s}_i $

is a binary variable indicating the ith observation’s socialization location (urban or rural);

![]() $ {r}_i $

is a binary variable indicating region of residence at time of survey (North or South);

$ {r}_i $

is a binary variable indicating region of residence at time of survey (North or South);

![]() $ {b}_i $

is a binary variable indicating ethnicity (Black or White), beta coefficients four through six correspond to the respective interactions of these variables, and the

$ {b}_i $

is a binary variable indicating ethnicity (Black or White), beta coefficients four through six correspond to the respective interactions of these variables, and the

![]() $ {x}_{ij} $

represent covariates discussed below. I make the usual assumptions concerning the error term. All regions not Census-classified South are classified North.

$ {x}_{ij} $

represent covariates discussed below. I make the usual assumptions concerning the error term. All regions not Census-classified South are classified North.

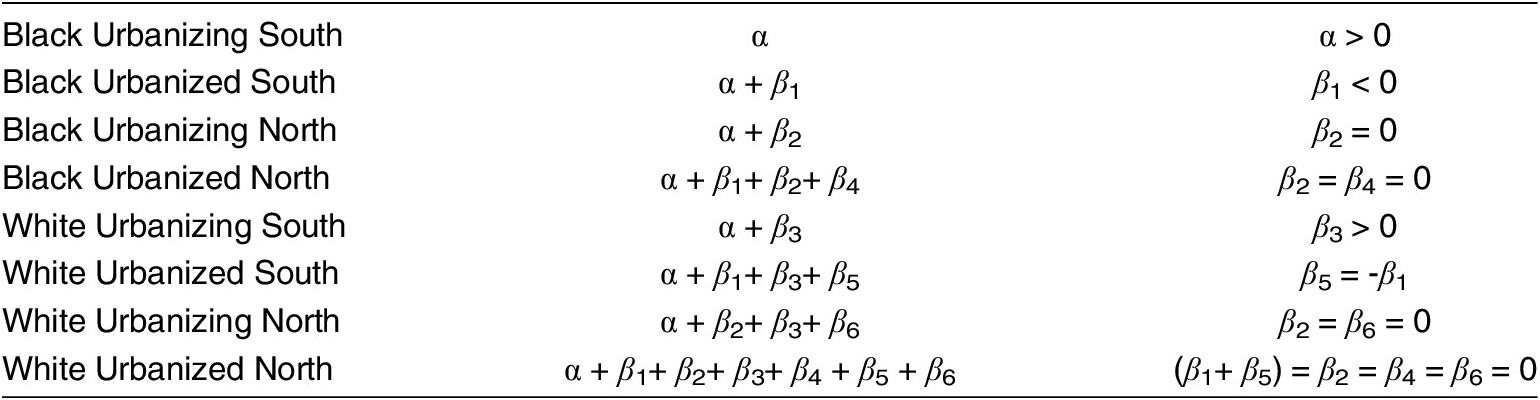

Theoretical Predictions and Results of Logistic Regressions

Table 2 summarizes, for each of the eight relevant household-head status positions, the regression model’s estimate of the relevant logit (in terms of the coefficients), and the predicted signs of and relationships between the coefficients implied by my theoretical argument. In terms of the parameters to be estimated, each row entry in column two represents the model’s estimate of the log odds that a household head in column one’s indicated status group is two-parent. Column three displays the theory’s prediction concerning the signs of and any specific relationships between the estimated parameters. The reader should observe that the entries in column three represent the sharpest interpretation of the theoretical argument possible, (i.e., all discernible effects of socialization location on the likelihood of a family being two-parent are independent of region and discernable for Blacks but not Whites). In this regard, in addition to the theory’s prediction that urban socialization location has a negative effect on the log odds a Black family is two-parent (

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_1 $

< 0), and there are no main or interactive regional effects (

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_1 $

< 0), and there are no main or interactive regional effects (

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_2 $

=

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_2 $

=

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_4 $

=

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_4 $

=

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_6 $

= 0), I call special attention to the theory’s strong prediction that socialization location has no effect on the log odds a White family is two-parent (

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_6 $

= 0), I call special attention to the theory’s strong prediction that socialization location has no effect on the log odds a White family is two-parent (

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_5 $

= −

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_5 $

= −

![]() $ {\unicode{x03B2}}_1 $

). As discussed earlier, nothing in the theory suggests the superordinate group should be affected by socialization location.

$ {\unicode{x03B2}}_1 $

). As discussed earlier, nothing in the theory suggests the superordinate group should be affected by socialization location.

Table 2. The Prediction Structure of the Regression Model

Table 3 displays the actual results for the model without covariates. The model with covariates is discussed in the section on robustness. Estimation of the full model verified that both the main effect of region and its interactive effects with other variables were statistically insignificant at the five percent level and the hypothesis that the relevant coefficients equal zero cannot be rejected. I conclude, with respect to family formation, the effects of race and socialization location are independent of region, and applying Occam’s Razor, the regression results shown in Table 3 use the minimal set of predictor variables necessary to test the primary hypotheses generated by the theory. This first set of predictors contains four binary categorical variables named race (coded 0 = Black, 1 = White), socialization location (coded 0 = urbanizing, 1 = urbanized), region (coded 0 = Southern residence, 1 = Northern residence), and an interaction between socialization location and race. Status of the family head determined variable coding. All results refer to families living in urban areas (roughly defined by the census as jurisdictions of population 2500 or greater).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Predicting Log Odds of 2-Parent Family

The reference group for model 1 is urbanizing Blacks living in the South. For this group, the constant term 1.008 in the second row of Table 3 is the estimated log odds of being two-parent. Exponentiation of this constant term gives 2.74 as the odds that a Black urbanizing family in the South is two-parent. These odds imply the estimated probability .73. The coefficient for region estimates the difference in the log-odds of being two-parent between the reference group and a Black urbanizing family living in the North. Region’s coefficient is negative but small and, as predicted, the coefficient for region (𝛽2) is not statistically significant, and we cannot reject the hypothesis that the coefficient is zero. Moving to column five we see that for Blacks the odds an urbanizing family residing in the North is two-parent is .975 times the odds for the reference group, giving estimated odds of 2.67 and a probability equal to .728 virtually equal to the reference group. Thus, as displayed in the lower part of Table 3, the probability that a Black urbanizing family living in the South is two-parent is equivalent to the probability for a Black urbanizing family living in the North. With respect to family formation behavior, Blacks socialized in rural areas behaved no different in the urban South than in the urban North. The coefficient for socialization location estimates the difference in the log-odds of being two-parent between the reference group and a Black urbanized family living in the South. The estimated effects of changing from an urbanizing to an urbanized Black family in the South are negative and statistically significant with a p value of .001. The estimated odds that a Black urbanized family in the South is two-parent is .784 times the odds of a similarly situated urbanizing Black family, and we estimate the probability that an urbanized Black family in the South is two-parent at .683. Given the statistical significance of the coefficient for socialization location, we reject the hypothesis that the log odds of being two-parent are the same for urbanized and urbanizing Black families in the South. From the table it is clear the log odds of being two-parent are also different for urbanized and urbanizing Black families in the North. Moreover, comparing urbanized families in the South and North, we cannot reject the hypothesis that there is no difference in the log-odds of being two-parent. As with the urbanizing, urbanized Blacks behave similarly North and South. Intra- and inter-regional differences between Black urbanized and urbanizing households are virtually identical. Socialization location appears to be so powerful a conditioner of household formation patterns it is independent of region in the strongest sense.

The remaining two coefficients in Table 3 provide estimates of the effects of race on the log odds of a family being two-parent. The coefficient on race is an estimate of the pure race effect, the difference in the log-odds of being two-parent for Black and White urbanizing families living in the urban South. As predicted, this pure race effect is positive, large, and statistically significant with a p value less than .0005.

I reject the hypothesis that urbanizing Black and White families in the South have equal log odds of being two-parent; the odds of an urbanizing Southern family whose head is White being two-parent is 3.21 times the odds for a similarly situated family whose head is Black, and the estimated probability for the urbanizing Southern White family is .898. Finally, the coefficient for the race-socialization location interaction term provides a test of the hypothesis that the effects of socialization location are different for Blacks and Whites. The interaction coefficient is positive and statistically significant allowing rejection of the hypothesis that the effects of rural and urban socialization are equal for Blacks and Whites.

The odds an urbanized Southern family that is White is two-parent (3.213*.784*1.24*2.74) equals 8.55 and its estimated probability of being two-parent is .895, indicating no difference between urbanized and urbanizing families whose heads are White in the South. Or equivalently, as implied by the theory and confirmed by an F test, the interaction effect of race and socialization location cancels the main effect of socialization location (see row six, column 3 of Table 2 and in Table 3 rows four and five of column 2). Analogously, the estimated probability for an urbanized White family in the North is .892. We conclude that the effects of urban versus rural socialization on family formation depend on race; for Whites there are no differential effects, the predicted probabilities for urbanized and urbanizing are equivalent; for Blacks there is a significant difference, the odds a Black urbanized family is two-parent is about four-fifths the odds of an urbanizing Black family.

These results clearly discredit the Northern cultural deficit hypothesis. Among Blacks, the urbanizing outperformed the urbanized in the South and the North. Including the race variable and the race-socialization location interaction is equivalent to having a placebo group (Whites) and the results on the coefficients for these controls strongly rule out the possibility the results for Blacks are due to some spurious artifact in the data. The finding of no socialization location effects for Whites also discredits the hypothesis that rural to urban Black migrants were selected according to some unobserved trait independent of their socialization location that increased the likelihood of their maintaining two parent families. The finding of no socialization location effect for Whites implies the location effect for Blacks is not in the Black migrant’s individual characteristics but in the economic ecological system of their destination, urban America. Supporting this, strong evidence says Black rural-to-urban migrants of the mid-twentieth century were not a population self-selecting according to some individualized trait predictive of stable two-parent families. Between 1940 and 1970, most of the Black rural population migrated to a town or city as the mechanization of cotton farming reduced landowners’ demand for labor, practically wiping out entire plantation labor forces. When nearly everyone migrates, selectivity is highly unlikely, a conclusion also confirmed by Leah Platt Boustan’s (Reference Boustan2016) finding that Southern migrants to the North were not especially selected, either positively or negatively. Moreover, if there were selectivity in who migrated from rural areas, it was exactly the opposite of that required to cast doubt on my results. Single parent families headed by a woman were generally untenable in farming areas, and they were generally the first to migrate into town (see Table 5 and its discussion).

I conclude discussion of this model with reports of additional tests examining the robustness of the estimated coefficients on race and socialization location by augmenting the simplest model with additional predictors. Augmenting the model with additional covariates such as schooling or age of the family head and interactions with race (whether categorical or continuous) and family income further substantiates these results. I call attention to three points: 1) schooling is a significant positive predictor of family formation; 2) augmented models produce trivial changes in the coefficient estimates for race, socialization location and their interaction and usually improve the significance level of the interaction term, suggesting that 3) the coefficient estimates are quite robust to alternative specifications of the model. Recoding categorical variables to test robustness of main effects also produced results confirming the predictions of the theory, as did recasting the regression as a linear probability model.

Prediction of a family’s poverty status also confirms the statistical significance of rural versus urban socialization location and race. Table 4 presents output from a logistic regression estimating the log odds a family is in poverty. I include the results from this analysis because key differences in the interaction between race and socialization location are especially illuminating. Substituting poverty status as the dependent variable, model 2 of Table 4 duplicates the independent or predictor variables of model 1 in Table 3. As is expected, because of higher wages in the North than South, unlike the case for two-parenthood, region is a significant predictor of poverty; the predicted odds that an urbanizing Black family in the North is poor are only about .57 of the predicted odds for a similar family in the South. Also note that socialization location remains significant and positive; an urbanized Black family in the South has odds of being in poverty 1.25 times higher than an urbanizing Black family living in the same region.

Table 4. Logistic Regression Predicting Log Odds of Family Poverty Status

I also tested for interaction effects between race, region, and socialization location asking if socialization location had a different effect on poverty for Blacks than Whites or in the South versus the North. The findings for these interactions are especially illuminating. For poverty, although estimates of the race socialization location interaction show that the effects of socialization location depend significantly on race, the race effects are in opposite directions. Although urbanized Blacks face higher odds of being poor than do urbanizing Blacks, for Whites these odds were reversed. Urbanized Whites faced odds only .55 the odds of urbanizing Whites. This latter finding is consistent with findings of sociologists that Southern White migrants living in Northern cities displayed higher rates of poverty, more joblessness, and were more likely to be on public welfare than were Northern-born Whites in Northern cities. The tests also provide similar results for Southern Whites living in Southern cities. Augmenting the independent variables with predictors such as gender, education, and full-time work status of the family head leaves the estimated effects of race, socialization location, and their interaction intact and statistically significant. I conclude from the results of these hypothesis tests, as predicted by the theory, socialization location is a significant predictor of Black behavioral outcomes, and that urban socialization has a negative effect for Blacks but not Whites.

The poverty findings for Whites are what should be expected under the common-sense hypothesis that Whites migrating to the city (in any region) faced adjustment obstacles not affecting resident Whites. Researchers who erroneously hypothesized that Blacks migrating to the North were responsible for rising poverty, joblessness, and concomitant problems in Northern cities, applied this commonsense approach. However, White behaviors are not reliable indicators of Black behaviors. The nation’s pathological race relations structured different patterns of behavior among Blacks and Whites, and it is not reasonable to expect Blacks would uniformly respond to given situations as did Whites. Whites did not undergo severe ordeals of discrimination in either rural or urban environments. Thus, urbanized Whites did not develop behavioral defense mechanisms to cope with day-to-day assaults on their self-worth. The lack of comparable findings among Whites strongly supports the hypothesis that urbanizing/urbanized behavioral differences among Blacks were due to divergent processes of socialization supporting different constructions of social identity and agency.

Evidence of 19th Century Urbanized/Urbanizing Differences

The regression results show the differential behavior of Northern-born and Southern-born Blacks residing in Northern cities is better understood as differences between the urbanized and urbanizing. Reinterpret Northern-born and Southern-born Blacks as representing respectively, the urbanized and urbanizing. For Blacks born before 1950 these designations are excellent proxies. Northern-born Blacks were virtually all urbanized and the Southern-born were overwhelmingly raised in rural areas. Relabeling data this way suggests urbanizing/urbanized differences in family structure have deep historical roots.

Comparing the proportion of two-parent families among free-born Blacks and ex-slaves in 1847 Philadelphia, Furstenburg and colleagues (Reference Furstenburg, Hershberg and Modell1975) found ex-slaves (more likely to have rural origins) more often lived in two-parent households than did the free-born (who were overwhelmingly urbanized). They also found two-parent families were more prevalent among Southern-born than Northern-born Blacks in Philadelphia during 1880, a finding also true for Boston (Pleck Reference Pleck1972). In Boston, a large majority of the Northern-born were urbanized, most within Boston, but a higher Southern-born Black population combined with higher marital rates among the Southern-born meant the urbanizing dominated statistics describing households with children. Despite Elizabeth H. Pleck’s computations combining husband-wife couples with and without children biasing downward the proportion of children in one-parent families, the proportion among Massachusetts-born Blacks was 28% compared to 17% for the Southern-born. Franklin E. Frazier (Reference Frazier1939) and Herbert G. Gutman (Reference Gutman1976) found higher rates of mother-only families in Southern cities than rural areas. Using methods like Pleck’s, Gutman’s downward biased estimates for the period 1865–1880 found the highest proportions of mother-only families in Southern locations were in cities: Natchez 30%, Beaufort 30%, Richmond 27%, and Mobile 26%. Each of the rural areas he examined had rates below 19%. These findings hold consistently from the 1930 census (where Black mother-only households were more prevalent in urban areas (25.2%) than farm areas (10.5 %)) onwards. Frazier (examining the 1920 through 1940 censuses) found similar results for rural and urban areas in the South.

A full assessment of this theoretical framework requires supplementing the quantitative data presented here with qualitative evidence that investigates the attitudes of rural, urbanizing, and urbanized Blacks toward major social institutions and race relations. For example, Blacks socialized in urban environments held quite different attitudes toward discriminatory labor markets than did their urbanizing neighbors who were generally more resigned to accommodating themselves to subordinate racial roles in low pay jobs (Brown Reference Brown1965; Ovington Reference Ovington1911). The remainder of the paper provides more substance for the argument.

Socialization in Two Black Enclaves

The discussion of Black children’s socialization centers on the role of labor market discrimination and its effects on household formation patterns in two distinct Black enclaves hosting two Black enclave economies. The first enclave is the segregated black-belt agricultural communities of the agrarian South; the second is the black/grey and illegal enterprise and employment industries within Black ghettos. The determining characteristics of an ethnic enclave are a geographically defined area inhabited by an ethnic group maintaining lifestyles separate from the peoples surrounding them. Its close relative, ethnic enclave economy, requires: 1) The enclave be spatially bounded from the main economy enabling an internal labor market dominated by minority labor to function; 2) The minority group be large enough and sufficiently diversified in resources (human or physical) to employ or (through network ties) guarantee group members access to employment (Portes Reference Portes1981). The following discussion focuses on the specific features of these two enclaves that shaped different socialization experiences responsible for the divergent attitudes and behaviors of urbanized and urbanizing Blacks. Each enclave offered Blacks opportunity to avoid demeaning interactions with White coworkers, but differences in the means available to do so structured distinct behaviors across the enclaves as well as distinct gender practices within each. Both enclaves’ economic structures enticed Blacks to overestimate opportunities for gaining social status while blocking their social and economic incorporation into the wider society. The agrarian enclave incentivized mainstream labor force participation and two-parent families, the urban enclave disproportionately socialized adolescents to dissociate themselves from these institutions.

Self-verification—social affirmation that one’s beliefs about oneself (one’s identities) are true—inspires agency, adoption of a life plan one believes both worthwhile and attainable. Self-verification elicits economic behavior because Blacks’ major interactions with Whites undermining their self-regarding identities occur in economic transactions (e.g., in job markets permeated with pathological race relations). Confronting Whites’ expectation that they efface themselves by assuming subordinate roles, generations of Blacks avoided Whites to escape demeaning race relations that stripped them of dignity and self-respect. The most frequent agency of avoidance was to seek self-employment to minimize interactions with Whites (Johnson Reference Johnson1943). The sharecropping tenancy system of the rural South developed substantially because Black families aspired to be free to work their own farms independent of day-to-day White supervision (Jaynes Reference Jaynes1986, Ransom and Sutch, Reference Ransom and Sutch1978). Urban Blacks avoiding Whites turned to the enclave economy’s extra-legal activities like gambling and trade in banned substances or in legal low-pay self-employment. These alternatives structured distinct household formation and reproduction patterns.

The Agrarian Enclave

Table 5 exhibits five major differences in the structural characteristics of agrarian and urban enclaves that socialized Black children so differently. The most important features involved the organization of labor markets, household production and domestic relations, and how each interacted with race and gender relations. Agrarian spatial location of residence and work coincided. Societal norms enabling greater exploitation of Blacks created enclaves within Black Belt counties where individual Black-White competition for jobs was attenuated providing Blacks dense employment networks. Parents’ ability to transfer social capital (employment networks and farming skills) to children incentivized adolescents to formulate life plans that envisioned climbing the agricultural tenancy ladder from sharecropper to landowner. Alabama cotton farmers Ned and Hannah Cobb exemplified these aspirations. Married in 1906 when Ned was twenty-one, they worked together, raised a family, and rose from sharecroppers to landowners (Rosengarten Reference Rosengarten1974). The Cobbs’ dream was common. Dr. Margaret T. Burroughs, born in 1917 in St Rose Parish, Louisiana, recalled her parents “didn’t have much but a dream to one day own their own land”—a dream they fulfilled (Reference Burroughs2003, p. 28). Cincinnati born Ossie Guffy’s paternal grandfather boasted, during the 1930s, “My daddy was a slave and here I am, owning my own farm and minister to a good congregation of respectable folks, trusted by white and black alike” (1971, p. 36). As late as the 1950s, civil rights activist Anne Moody’s stepfather Raymond, obsessed with sharecropping, was “talking about becoming a big-time farmer, raising lots of kids, making plenty of money, and becoming his own man” (1968, p. 90).

Table 5. Major Sources of Agrarian and Urban Socialization Differences

Although these aspirations were based on inflated perceptions of economic mobility up the tenure ladder, rural children’s strong personal efficacy was based on factually observing Black landowners. The odds a Black sharecropper family could someday achieve landownership were always low but positive. A survey examining the working careers of nearly one thousand Alabama farmers compiled during 1933 found that among those who began their careers as sharecroppers, about forty-five percent were still sharecropping while only about six percent had become landowners (Alston and Ferrie, Reference Alston and Ferrie2005; Black and Allen, Reference Black and Allen1937). The chances of climbing from sharecropper to owner were only one in sixteen. However, the odds a sharecropper could “rise up” as Ned Cobb put it (Rosengarten Reference Rosengarten1974, p. 121), had been higher during earlier periods. During 1910 and 1930, about one in eight Black male farmers owned their farm, so the chances were greater before the 1930s. Moreover, for couples discussing a shared life plan like the Cobbs, it was likely comforting knowing that those who failed to own, could still ascend above sharecropping to become renters. A 1938 study encompassing the entire South found that although 55% of men who had started their careers as sharecroppers were still sharecropping at the time of the survey, 39% had advanced to become either renters or owners (Woofter Reference Woofter1936). Alston and Ferrie’s (Reference Alston and Ferrie2005) analysis of Jefferson County, Arkansas found similar tenure mobility in one of the Black Belt’s most productive cotton producing counties. With Blacks’ population exceeding eighty percent, during 1930, 9.4% of the county’s Black farmers were owners; during a ten-year period, 39% of men who were laborers or sharecroppers during their twenties rose to become either higher status renters or owners within ten years (Alston and Ferrie, Reference Alston and Ferrie2005; Wright Reference Wright1986).

Striving for these life goals extracted a heavy price. Successful strivers had to comply with White supremacy, and most adolescents were socialized to conform. Literally founded on the joint labor supply of husband-wife families, the symbiotic relationship between marriage and sharecropping strongly reinforced cultural desires to marry and cohabit with children. The instrumental value of competent parental training for future work skills within the technologically stagnant rural economy combined with Blacks’ strong employment networks across the tenancy ladder undergirded parental authority over children aspiring to a life of farming. Organized on a gendered division of labor based in patriarchy, men entered contracts for the family, wives and daughters worked primarily in the house and garden, men and sons in the field; single women were not economically viable to landlords. The major mechanisms of rural socialization were planter authority, parental authority at home and thus also at work, church, and school. Each stressed conformity to subordinate racial behavioral roles (Alston and Ferrie, Reference Alston and Ferrie1993; Raper Reference Raper1974; Woofter Reference Woofter1936). Charles S. Johnson’s (Reference Johnson1941) survey and interview study of Black Belt counties concluded that rural Black youth learned early to avoid confrontation with Whites by obeying rules of racial etiquette. Ned Cobb recalled, “my daddy told me, many a time, to obey the white man, do what he tell you to do and avoid trouble; and also, even my daddy’s ways and actions told me that … he shunned white people, never did give a white man no trouble” (Rosengarten Reference Rosengarten1974, p. 48). Importantly, although adolescents’ beliefs about becoming landowners or rental tenants were inflated, failure to self-verify occurred relatively late in adulthood when disruptive and rebellious behaviors were unlikely.

The Urban Enclave

Unlike agrarian, urban employment provided no structural glue reinforcing cultural values to marry and remain so. Urban spaces were residentially segregated but work generally required leaving home for jobs untethered to household structure in occupations organized around racialized and gendered divisions of labor. Moreover, the low-wages and severe instability of Black men’s jobs reduced Black men’s economic value, undermining male ego gratification and straining the fabric of husband-wife families.

Black male job seekers competed directly with Whites. White norms promoting racial stratification either structured segregation across industries or erected workplace job ceilings with each truncating Blacks’ occupational opportunities and employment networks. Black women’s domination of sub-living wage domestic service occupations ensured them job stability but at the lowest wages of any group. Anthropologist Hortense Powdermaker’s (Reference Powdermaker1939) ethnographic research in Indianola, Mississippi during the Great Depression laid out the key determinants of urban Black family relations:

-

• High demand for domestic workers by Whites ensured greater employment opportunities for Black women than for the men.

-

• The town jobs White men wanted were unavailable to Black men, the Negro jobs available to Black men were unacceptable to White men.

-

• Among Black lower classes, the earning capabilities of women exceeded those of men, and generally the woman was a family’s chief breadwinner.

The textile industry, the South’s largest employer of White labor, epitomized these conditions. Like plantations, textile mills hired entire families providing structural support for the family cohesion of migrating rural-to-urban Whites. Blacks were excluded from mill villages and all but the lowest paying textile jobs getting less than 5% of industry employment until the 1960s, (Heckman and Payner, Reference Heckman and Payner1989; Wright Reference Wright1986).

Powdermaker’s (Reference Powdermaker1939) observations were small town Southern versions of urban labor markets everywhere. Ethnographers like Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1899) and Mary White Ovington (Reference Ovington1911) and participant-observer historians like Carter G. Woodson and Lorenzo Greene (Reference Woodson and Greene1930) documented the same conditions in Philadelphia, New York City, Xenia, Ohio, and Boston. Discussing findings similar to Powdermaker’s, Du Bois and Kelly Miller (Reference Miller1908) argued unstable low-wage male jobs fragmented urban Black husband-wife families due to an insufficient pool of marriageable men, anticipating late-twentieth century arguments that low gender earnings differences explain urban Blacks’ lower marriage rates (Becker Reference Becker and Schultz1974; Farley Reference Farley1988; Wilson Reference Wilson1987).

Urbanizing parents stressing conformity to subordinate racial roles precipitated conflict with children who internalized equalitarian values from school and peers. South and North, children were ashamed of their parents’ transporting rural Southern behaviors to urban settings. Blacks, reacting like Cincinnati raised Ossie Guffy (Reference Guffy1971), aghast at her grandfather’s hat-in-hand kowtowing to a White man during her visit to Georgia, bequeathed first-person accounts of childhood conflicts with urbanizing parents (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1963; Brown Reference Brown1965; Mebane Reference Mebane1981; Moody Reference Moody1968).

Diminished social capital reduced parents’ authority and stature as role-models. Parents’ thin employment networks concentrated in dead-end jobs and their low competence negotiating now-important school bureaucracies shifted the locus of children’s socialization toward schools and adolescent peers who criticized racialized job networks. Ethnographer Elijah Anderson’s (Reference Anderson, Anderson and Sawhill1980) findings that many young urban men were disdainful of adult mentors working at low status jobs or good jobs in declining industries not hiring also receives first-person confirmations (Brown Reference Brown1965; McCall Reference McCall1994; Malcom X and Haley, Reference Malcolm and Haley1965). Urbanizing adults lost influence as role models and conduits into job networks to younger adults who appeared successful in the underground economy.

Freedom and Agency among Urbanized Men

Adolescents’ inability to forecast an acceptable self-image evokes a response, frequently, a defensive evasive attempt to avoid the offending institutions and settings or an offensive intense engagement with them that seeks to change one’s reception. Evasive agencies center on coping strategies (e.g., dropping out of mainstream labor markets to work in grey and black-market activities to avoid racist interactions). Such agencies had long been part of urban Blacks’ cultural repertoire, and urban youth had a large supply of role models exhibiting such agencies (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1962; Brown Reference Brown1965; Malcolm X and Haley, Reference Malcolm and Haley1965). A Black professional living in Indianapolis, Indiana in 1908 explains the then already existing issues of identity and agency confronting urbanized youth:

Here are our young people educated in the schools, capable of doing good work in many occupations where skill and intelligence are required and yet with few opportunities opening for them. They don’t want to dig ditches or become porters or valets any more than intelligent white boys: they are human. The result is that some of them drop back into idle discouragement—or worse (Baker Reference Baker1964, pp. 131-132).

The one in eleven young urbanized Black men in the SEO data described earlier, who were neither in school nor working, were mid-century examples of this “idle discouragement or worse”. Avoiding the pathological racism systemic to American labor markets, many were avoiding mainstream jobs to take black market and illegal employment. Research covering the urban uprisings of the 1960s illuminates who these men were and what role they assumed in restructuring Black families. Coincidentally, during the final phase of the SEO, surveys of “riot-participators” compiled during the urban rebellions of the summer of 1967 provide evidence of the divergent effects of urban versus rural socialization and the rise of a subpopulation of urbanized Black males steeped in agencies of resistance. Conforming to the profiles of the young Black men Anderson (Reference Anderson, Anderson and Sawhill1980) studied in Philadelphia during the late 1970s, surveys found, the “typical rioter” was an “unmarried male between the ages of 15 and 24” who had been a life-long resident of the city in which he rebelled (i.e. a prototypical urbanized male). Contrary to the public’s beliefs, the “typical rioter” was not a disenchanted rural-to-urban migrant; the urbanizing migrants to the city were more likely to have been either “counter-rioters”—those who actively worked to stop the violence—or not involved. Compared to the urbanizing “non-rioters” the urbanized typical “rioter” felt “strongly” he was qualified for better jobs than he was getting and was deeply conscious of being barred by discrimination from jobs he felt he deserved. He was better educated and more aware of political personalities and events, but also “extremely distrustful” of the political system and political leaders. Sporadically employed and not working full-time when employed, compared to “non-rioters,” he expressed greater attachment to African sources of identity, beliefs Blacks are superior to Whites, rejection of White stereotypes of Blacks, and significantly, was “equally hostile toward middle class blacks and whites” (National Advisory Commission 1968, pp. 128-135; Jaynes and Williams, Reference Jaynes and Williams1989).

Despite the risks involved in black-market jobs, young men and women found it easy to discount or completely ignore the risks of such careers. With hopes of rising to a position of wealth and ghetto fame, throughout the twentieth century they entered the numbers industry (a form of lottery gambling formerly labeled illegal by authorities that was ubiquitous in urban Black enclaves) and later drug markets (Jaynes Reference Jaynes2023b, White et al., Reference White, Garton and White2010). Young men and women choosing the lifestyle carved out a social existence similar in some of its structural features to the tenant farming of the rural South. Whether it was landownership in the rural South or wealth and prestige as an urban hustler, seeing Blacks who had gained the prize was visible confirmation one could attain the highest success. Open access to the chase provided the opportunity for young people to aspire for self-esteem by pursuing a life plan they could value and confidently believe in their capacity to execute. The enclaves were similar in another respect. Confident they would defy the odds against success, eager young entrants to the chase in numbers and later drug markets, analogous to most sharecroppers who found themselves landless and poor at middle-age, would learn crime usually leads to lengthy periods of incarceration or to a violent end to a short life. Their behaviors placed considerable stress on two-parent families. How did urbanized women coping with missing or economically weak men persevere?

Freedom and Agency among Urbanized Mothers

Although Black women worked in illegal activities at higher rates than generally understood (e.g., numbers gambling) (Jaynes Reference Jaynes2023a), urban Black women searching for respect under the difficult mating conditions shaped by racially gendered labor markets verified self-worth differently. Indicative of this was the central economic and cultural role assumed by urban Black washerwomen. An 1849 census of Philadelphia, listing hundreds more employed Black women than men, revealed nearly one-half (1970 of 4249) of working Black women were laundresses (Frazier Reference Frazier1939). Fifty years later, social worker Isabel Eaton found 70% of Black women domestics in Philadelphia’s seventh ward were laundresses (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1899, pp. 431, 504). During 1835, a city ward of Cincinnati, Ohio reporting twenty-seven employed Black women and men listed eighteen washerwomen (Woodson and Green, Reference Woodson and Greene1930). The overwhelming presence of washerwomen in the social and cultural life of Black communities may be inferred from the fact that Macon, Georgia, licensed 1200 washerwomen in a city with only about 18,000 total Blacks (The Atlanta Constitution, 1910). In 1920, washerwomen composed 30% of more than 900,000 Black women working outside agriculture nationwide.

Although more Black women, 40%, worked as domestic servants, I focus on washerwomen because washerwoman was likely the most typical occupation of urban Black mothers. The reasons were twofold. Although 80% of Black women employed outside agriculture provided personal services to Whites, unlike household servants, washerwomen with childcare and homemaking responsibilities could remain at home with their children. Secondly, conducting what was poorly paid self-employment, washerwomen working at home minimized psychologically debilitating contacts with Whites demanding obsequious behavior. For these benefits, homemaking and child-care and independence from Whites, Black mothers often accepted a smaller income than could be earned by going out to service.

The cultural formations washerwomen forged provide additional perspectives for viewing Patricia Hill Collins’ (Reference Collins2000) point that Black women have seen work in their households as a form of resistance. Retired District of Columbia domestic workers (all born between 1884 and 1911) “identified laundresses as critical figures in their search for autonomy” (Clark-Lewis Reference Clark-Lewis, Groneman and Norton1987, p. 204). For these Black women “laundresses served as role models” because they were not tethered to employers exacting mistress/servant relations under live-in 24/7 or day-worker conditions (Clark-Lewis Reference Clark-Lewis, Groneman and Norton1987, p. 200). Like their sharecropper relatives in the countryside who frequently exercised their freedom to change landlords, the domestics ranked freedom from the surveillance and control of a White householder highly. The degree of autonomy this gave women in the intersectional social roles they might assume (stay at home mother, wife, church pillar, mentor) was highly prized. Mother-only families headed by washerwomen were likely always a central force in the “culture” of Black urban communities.

Serving as role-models for young women, self-employed washerwomen (married and single-mothers), labored in communal spaces safely harbored within their own neighborhoods (Hunter Reference Hunter1997). Within these spaces, they formed ties of kinship and sisterhood indispensable to urban communities desolated by low-earnings and erratically employed men. Observing the disproportionate presence of Black Manhattan’s mother-only families near 1900, social worker Mary White Ovington (Reference Ovington1911) offers a clue to the historical roots of twenty-first-century cultural practices infused with kinship networks, economic reciprocity, and independent minded women finding status fulfillment through motherhood. Combining census research with up-close observation, she anticipated more recent demographers’ findings that, historically, Black households were more likely multi-generational than White households (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, McDaniel, Miller and Preston1993). Always analytical, Ovington explained, arguing Black grandmothers accustomed to lives of “hard labor” were important contributors to the households of working daughters and were treated with respect and consideration; elderly White women were not so economically valuable to their stay-at-home daughters (1911, pp. 78-79). Were these multigenerational and mixed kinship households cultural formations? Certainly, but they were also adaptations to economic conditions created by stratified urban labor markets and missing and underpaid men.

Conclusion

The proposition that mother-only families were historically a strikingly high minority of urbanized Black families has important implications for a large ethnographic literature positing the existence of an urban Black culture centered around single women who view motherhood an attractive pathway to economic independence and social status (Geronimus Reference Geronimus1987; Ladner Reference Ladner1971; Stack Reference Stack1974; Waller Reference Waller and Lamont1999). Contemporary observations of “cultural” formations among women pursuing survival and personal development through single motherhood (although evolved to adapt to contemporary society) reflect continuities of sisterhood and kinship ties inherited from historical generations. Much of what is labeled culture today are adaptations to longstanding structural barriers.

There is a revealing sameness to the descriptions provided by twenty-first century ethnographers of Black urban enclaves and historical studies of the antebellum free Black population. Contemporary urban enclaves offer low-skilled people below living-wages, monotonous, and irksomely supervised service-sector jobs many describe as “lifeless, dead-end things, passed around in meaningless lateral moves” promising no chance to progress (Hamer Reference Hamer2011, p. 76). Or, attempting to climb a deceptively appealing status ladder by seeking what Nikki Jones (Reference Jones2018) calls positive identities against difficult constraints, they supplement mainstream jobs with “clean” hustles (off-the-books otherwise legal work), or “dirty” hustles like drug trafficking (Hamer Reference Hamer2011, p. 76). Historians of the antebellum free Black population describe similar conditions shackling the lives of a mostly urbanized group facing racist legal restrictions and fierce job discrimination (Curry Reference Curry1981; Davis Reference Davis1975; Kusmer Reference Kusmer1991; Litwack Reference Litwack1961). One major difference between 1850 and 2023 is class differentiation—antebellum free Blacks were crowded into urban enclaves regardless of class, while contemporary enclaves only house the most disadvantaged poor (Wilson Reference Wilson1987). Social science research must direct more attention to the legacy past adaptive behavior bequeathed current structures.

Throughout American history, urbanizing Blacks arrived in cities with a strong work ethic, high valuation of marriage, and a fundamentalist religious outlook. Many also arrived with negative to diffident attitudes toward formal schooling, a cultural attitude ingrained into generations of Black farmers functioning within a social structure dominated by employers dedicated to preventing the emergence of a discrepancy between farm worker’s educational attainments and the stagnant low skill techniques of Southern agriculture. The urbanized children of these migrants, frequently underachieving in school and confronted with employment discrimination in any case, perceived all paths to success blocked. The response of many second-generation Black urbanized youth followed two well-traveled paths taken by generations of urbanized Blacks throughout U.S. history. One path led toward social alienation and withdrawal, the other fierce engagement with institutions. Both challenged racial practices within America’s putatively democratic institutions. At mid-twentieth century, the difference from earlier periods was the tremendous volume of rural migration to America’s towns and cities, South and North. Tradition-oriented urbanizing migrants both hid the emerging behavioral transformation within average statistics and made the transformation possible as their procreation yielded fresh recruits for a long existing deeply alienated street-corner society and for an emergent middle class both becoming increasingly rebellious toward their pariah status. When most Blacks of procreation age had been socialized in urban settings, a jump in the proportion of children living without one or both parents occurred. This discontinuity in the data appears dramatic and perplexing in the absence of a thorough understanding of the complex child socialization changes structured by urbanization. Adaptations to urban racism seem as important as slavery to the fragmentation of Black families.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Reynolds Farley, Population Studies Center, University of Michigan; James Kung of the Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Hong Kong; and Brandon Terry, African and African American Studies and Social Studies, Harvard University for helpful conversations and to three anonymous referees for constructive critiques. All errors are owned by me. The author declares no competing interests.