The recent novel H1N1 influenza pandemic has once again raised the concern that during a severe pandemic respiratory illness, critical care (intensive care unit, ICU) and mechanical ventilation resources will be inadequate to meet the needs of patients. Fortunately, ventilator and ICU resources were not universally strained during the 2009 pandemic; however, shortages of isolation masks, vaccine doses, and other supplies led to rationing in several centers.

Several protocols for initial and ongoing triage of adult patients to critical care units or mechanical ventilator use during a pandemic respiratory illness have been published.Reference Hick and O’Laughlin1Reference Talmor, Jones, Rubinson, Howell and Shapiro2 After the severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Toronto, Canada, Christian and colleaguesReference Christian, Hawryluck and Wax3 proposed a triage system for ventilator access based on preexisting health status and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores. The NY Department of Health was the first US governmental body to issue a proposed triage system for ventilator access during a pandemic influenza event.Reference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 This system is similar to the Toronto proposalReference Christian, Hawryluck and Wax3 but has fewer exclusion criteria. Recent studies evaluating the performance of Toronto guidelines, as applied to retrospective patient populations,Reference Christian, Hamielec and Lazar5Reference Guest, Tantam, Donlin, Tantam, McMillan and Tillyard6Reference Khan, Hulme and Sherwood7 have shown that these guidelines have overpredicted mortality. They have also shown that some patients who may have a significant chance of survival would be erroneously assigned to the “expectant management” category. The NY guidelinesReference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 use less stringent exclusion criteria and may assign fewer patients to the expectant category.

None of the triage criteria designed for infectious disease disasters has included pediatric-specific recommendations. As the 2009 pandemic showed, respiratory illnesses do not spare, and may even disproportionately affect, children under the age of 18 years. Children differ significantly from adults in their physiologic and pathologic responses to respiratory disease. Triage systems derived using only adult-based criteria are clearly inappropriate for young children and may be inappropriate for adolescents. A recent review of the ethics literature addressing pediatric triage suggests that exclusion criteria appropriate for adults may not be appropriate for pediatric patients.Reference Antommaria, Sweney and Poss8 The Utah Department of Health has proposed pediatric inclusion/exclusion criteria based on expert opinion, and uses a clinical judgment component during ongoing triage (www.uha-utah.org, accessed Oct 1, 2010). Kanter and CooperReference Kanter and Cooper9 highlighted the need for pediatric-specific triage.

We performed a systematic review of the pediatric literature to evaluate possible pediatric critical care prognostic scoring systems for use in triage guidelines for children. Based on the findings of this review, we propose a modification of the NY adult ventilator triage guidelines,4 using appropriate pediatric criteria. Thus, we present a comprehensive triage system for all patients regardless of age. The results of the review and our proposed triage classification guidelines are presented here.

METHODS

We used multiple search engines including MEDLINE and EMBASE, using a search for terms and key words including multiple organ failure, multiple organ dysfunction, PELOD, PRISM III, pediatric risk of mortality score, pediatric logistic organ dysfunction, pediatric index of mortality pediatric multiple organ dysfunction score, “child+multiple organ failure + scoring system. ” Limits on the searches included English language and patients younger than18 years of age. Other references were obtained by reviewing all reference bibliographies of the articles selected by the searches.

Searches were conducted in the period January 2010-February 2010 by one of us (K.M.K.). All references were evaluated for inclusion into the study by reading their abstracts. Articles were included in the evaluation if they described scoring systems for pediatric mortality or illness prediction in critically ill patients and if they had reasonably large validation and development populations (more than 20 patients for each population). Articles containing subsequent validations, applications, and comparisons of different scoring systems were also included. A report was excluded if it used the scoring system only to describe severity of illness in a particular cohort of patients rather than validating the scoring system. Articles were excluded if they examined only narrow diagnosis mortality (ie, postoperative cardiac mortality) rather than a more general population of critical care patients, with one exception. Reports looking at sepsis as a proxy model for patients with multiple organ failure were included, as sepsis is a general final pathway for many pediatric critical care patients.

We reviewed the final set of articles with a focus on which prognostic score would be most appropriate for use in a triage tool for pediatric patients during a respiratory pandemic. Several requirements must be met to have parity with the adult triage tools. First, because this score may be used to deny access to lifesaving care, the scoring system should be designed using a large population and be validated in multiple institutions. Second, the score should be easy and fast to calculate, as scores will be needed for all presenting patients and staff resources will be limited during a pandemic. For the same reason, the scoring system should use minimal radiology or laboratory resources. Third, as the adult triage tools require a re-assessment of patient improvement as a requirement for continued resource use, the scoring system must be able to follow the progress of the patient throughout the course of the illness as well as on presentation. The scoring systems found in our review were then evaluated to determine if they met these criteria. The most appropriate of the systems was used to modify the NY guidelines to be appropriate for pediatric patients. As patient information was not used either prospectively or retrospectively, no institutional review board approval was needed.

RESULTS

The initial search resulted in 69 separate references with publication dates from 1988-2010. Articles that met the stipulated requirements (22) were reviewed in full (K.M.K. and M.M.L.) (Table 1). The search revealed eight scoring systems, of which five were independently derived. All scoring systems were pediatric-specific and include Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD) score,Reference Leteurtre, Duhamel, Grandbastien, Lacroix and Leclerc10Reference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11 Pediatric Risk of Mortality Score (PRISM),Reference Pollack, Ruttimann and Getson12 PRISM-III,Reference Pollack, Patel and Ruttimann13 PRISM-III–Acute Physiology Score (PRISM-III-APS),Reference Pollack, Patel and Ruttimann14 Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM),Reference Shann, Pearson, Slater and Wilkinson15 PIM-2,Reference Slater, Shann and Pearson16 Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (P-MODS),Reference Graciano, Balko, Rahn, Ahmad and Giroir17 and Signs of Inflammation in Children that can Kill (SICK).Reference Kumar, Thomas, Singhal, Puliyel and Sreenivas18Reference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19

TABLE 1 Articles Included in Systematic Review

Several recent articles have compared the use of different scoring systems for description of multiorgan failure in pediatric populations. These articles were included in the review and were used to inform the choice of scoring system. The report from the 2002 International Pediatric Sepsis Consensus conferenceReference Goldstein, Giroir and Randolph20 reviewed the existing organ dysfunction scoring systems that could be used to track changes in organ function. They concluded that no single system was perfect but that the PELOD score was the only multicenter validated scoring system. Kanter and CooperReference Kanter and Cooper9 reviewed several scoring systems for use in initial triage and determined that PIM-2 would be suitable for initial triage of pediatric patients. Lacroix and CottingReference Lacroix and Cotting21 reviewed the predictive scoring systems and descriptive scoring systems available to describe pediatric multiorgan dysfunction. The authors concluded that while PIM-2 and PRISM-III are both applicable for predicting mortality from initial presentation, only PELOD is validated to quantify severity of illness throughout the patient's progress. Dominguez and HuhReference Dominguez and Huh22 compared the P-MODS and PELOD scoring systems and concluded that the PELOD scoring system had the advantage of including neurologic impairment and had a broader validation population. PELOD was slightly better at predicting mortality than P-MODS. Table 2 describes the scoring system, development and validation populations, advantages, and disadvantages of each system for use in triage during a respiratory pandemic.

TABLE 2 Possible Pediatric Scoring Systems for Use in Triage Assignment

COMMENT

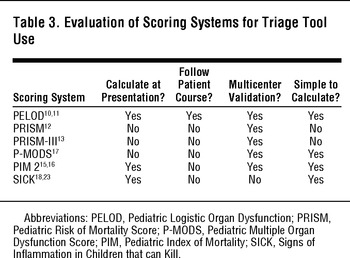

Of the possible scoring systems applicable for the generalized pediatric critical care population, the only score that fulfills all criteria required for use in modifying the NY state triage toolReference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 is the PELOD score.Reference Leteurtre, Duhamel, Grandbastien, Lacroix and Leclerc10Reference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11 Although PIM-2 is easy to calculate and can be determined at initial presentation, it does not follow the patient course or allow interval calculation. Table 3 evaluates the criteria for each scoring system.

TABLE 3 Evaluation of Scoring Systems for Triage Tool Use

The PELOD score was developed and validated using a multicenter, international design and has been validated in international studies.Reference Leteurtre, Duhamel, Grandbastien, Lacroix and Leclerc10Reference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11Reference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19 It has not been validated in the US population but has been evaluated in Canadian ICU studies. It is easily calculated and is in the public domain, making it useable even in community hospitals with a small pediatric population. Drawbacks to the PELOD score include the fact that it requires laboratory values including arterial blood gases, alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase, prothrombin time, creatinine, and complete blood cell count. It was designed and tested in 1999; the field of pediatric critical care medicine has improved during the past 10 years and thus PELOD scores may overpredict mortality. A recent external validation studyReference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19 showed that PELOD both overpredicted mortality and cannot distinguish predicted mortality in the range of 40% to 80% due to the discontinuous scoring system. These findings become an issue when comparing pediatric to adult patients, as the concern is that the mortality predicted by PELOD is too high compared with that of the SOFA scoring system. However, even with these limitations, the PELOD score is the best multiorgan failure prediction tool for ongoing triage of limited resources.

At this time, our recommendation is to base the pediatric triage ventilator guidelines on the PELOD scoring system.Reference Leteurtre, Duhamel, Grandbastien, Lacroix and Leclerc10Reference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11Table 4 shows the PELOD scoring system.

TABLE 4 PELOD Scoring SystemReference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11

We suggest matching the pediatric triage level for mortality with the adult SOFA mortality scoring to allow parity of triage guidelines for pediatric and adult patients. The calculation for determining predicted likelihood of mortality from PELOD scores is:

The PELOD scores are a discontinuous measure, and several intervals of predicted mortality are not calculable (40%-80%). To use the PELOD scoring system on a daily basis, the daily score is calculated in the same fashion as it is calculated at the initial presentation. If new data are not available (ie, new laboratory values) the value can either be assumed to be unchanged or normal, depending on the physician's clinical judgment.

The NY triage toolReference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 uses SOFA score cutoff points of less than 11 (predicted mortality of >90%)Reference Vincent, Moreno and Takala24 and 7 or less (predicted mortality of <20%). To match the predicted mortality of greater than 90% at a SOFA score greater than 11,Reference Vincent, Moreno and Takala24 we suggest using a PELOD score of 33. This score is a compromise of the predicted mortality of 100% using the development population of critical care patients in 1999 and using the recent validation study from South America,Reference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19 which suggests that the actual mortality at a PELOD score of 33 is 90.6%. Likewise, a PELOD score of less than 21 has a predicted mortality of less than 20%, which is on par with a SOFA score of less than 8. The predicted mortality, as from the initial PELOD model,Reference Leteurtre, Duhamel, Grandbastien, Lacroix and Leclerc10Reference Leteurtre, Martinot and Duhamel11 and the recent validationReference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19 are both less than 20% at the PELOD score of 21, and no modification is needed.

We propose a pediatric triage system for access to ventilators or ICU level care that mirrors the NY guidelines.Reference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 We would use the same exclusion criteria proposed in the guidelines, with the modification of using a PELOD score less than 33 as a substitute for the SOFA score of less than 11. Appropriateness of these criteria for pediatric patients must be addressed in future studies. We consider a similar four-category triage system using the same categories of Blue—expectant/palliative care only, Red— highest priority for scarce critical care resources, Yellow—intermediate priority for critical care resources, and Green—discharge from critical care (no significant organ failure). We also use a re-assessment of the patient's condition at 48 and 120 hours to ensure that patients demonstrate improvement with use of the resource. Lack of improvement may require re-assignment of the ventilator or other resource to other patients who are at higher priority for the resource. The triage decision tool for pediatric patients is detailed in the Figure.

Figure. Critical Care Triage Tool –Pediatric Patients (<18 y) (Top), and Exclusion Criteria (Bottom).

We acknowledge the significant limitations to the proposed pediatric triage tool presented here. All of the scoring systems described were developed to predict the likely prognosis for a cohort rather than individual patients. As with any mass disaster protocol, it is impossible to fully test or validate the tool except by simulation until the disaster happens. Several recent reports have shown that the performance of the adult triage tools using retrospective studies may inappropriately triage patients.Reference Christian, Hamielec and Lazar5Reference Guest, Tantam, Donlin, Tantam, McMillan and Tillyard6Reference Khan, Hulme and Sherwood7 The ease of implementation can be approximated but cannot be fully tested under the controlled case of a time-limited simulation. Christian et alReference Christian, Hamielec and Lazar5 showed that for providers not involved in the development of the TorontoReference Christian, Hawryluck and Wax3 triage tool, there may be significant inter-rater variability. We are also concerned that the significant progress and improvements in pediatric critical care during the past 10 years may lead to the PELOD scores being an overestimation of mortality risk for pediatric patients, which may put them in higher jeopardy when compared with adult patients using a SOFA scoring system. Several recent reports have shown that the performance of the adult triage tools using retrospective studies may inappropriately triage patients.Reference Christian, Hamielec and Lazar5Reference Guest, Tantam, Donlin, Tantam, McMillan and Tillyard6Reference Khan, Hulme and Sherwood7 Some recent evidence has shown that the TorontoReference Christian, Hawryluck and Wax3 triage guidelines may overestimate mortality for the excluded or expectant (Blue) group and poorly discriminate between patients who should be in the Red vs Yellow group.Reference Guest, Tantam, Donlin, Tantam, McMillan and Tillyard6 We believe that we have somewhat ameliorated this aspect by using the adjusted limit of PELOD = 33 in keeping with the most recent PELOD validation study.Reference Garcia, Eulmesekian and Branco19 We believe that extensive testing of our proposed pediatric tool using existing PICU patient groups concurrently with adult patient triage tools is needed to ensure accurate and fair triage for adult and pediatric patients.

CONCLUSIONS

After an extensive search of the literature, we found eight pediatric multiorgan dysfunction scoring systems. Of these, the one most amenable to use as a ventilator triage tool for pediatric patients during a respiratory pandemic is the PELOD score system. We have proposed a pediatric-specific triage protocol that may be implemented in parallel with the NY state triage protocol for adultsReference Powell, Christ and Birkhead4 so that pediatric and adult patients can be triaged for ventilator or critical care resources with parity during an epidemic. Further evaluation of this tool for both adults and children must be undertaken in the future to ensure an ethical distribution of critical resources. Re-evaluation and improvement in pediatric critical care prognostic scoring systems is also needed to provide accurate estimates of mortality in pediatric patients.

Funding/Support: Financial support was provided by University of Michigan, Department of Emergency Medicine departmental funds for fellow research.