Given predictions about climate change and the severity and frequency of natural hazard events including bushfires, floods, droughts, and heatwaves,Reference Colvin, Crimp, Lewis, Lukasiewicz and Baldwin 1 , 2 communities across the globe will likely be increasingly exposed to disaster events, including the additive and compounding impacts of successive disasters.Reference AghaKouchak, Huning and Chiang 3 There is also concern about the growing risk of infectious disease emergence due to anthropogenic environmental pressures.Reference Di Marco, Baker and Daszak 4 These events have the potential for significant impacts on access to social and health services, mental and physical health, mortality, and quality of life.

The Southeast coast of New South Wales, Australia, has experienced unrelenting disaster events. During 2019 and 2020, the region experienced severe bushfires that burned the largest land area ever recorded in a single fire season. 5 The fires burned through over 20 million hectares, destroyed over 3000 homes, and resulted in multiple deaths and significant environmental impact.Reference Nolan, Bowman and Clarke 6 Unprecedented bushfire smoke led to significant smoke-related illness.Reference Johnston, Borchers-Arriagada and Morgan 7 Although local data are not available, across Australia in the 2019-2020 fire season, bushfire smoke was estimated to have caused 429 premature deaths, 3230 hospital admissions, and 1523 emergency department presentations.Reference Johnston, Borchers-Arriagada and Morgan 7 Several fire-affected areas were subsequently impacted by flooding in 2020 and 2021, where the state of New South Wales recorded some of the wettest periods since 1900. 8 Then, in March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic was declared. Lockdowns, isolation, and social distancing requirements were introduced throughout 2020 and 2021. By June 2022, Australia had experienced an estimated 220 089 COVID-19 cases and some 9599 COVID-19 related deaths.Reference Storen 9 These events provided a unique opportunity to explore the impact of successive disasters on the community—namely, disruptions to communities affecting the environment, infrastructure, or social support networks, which inhibit the ability of older people to obtain health care.

The incidence of chronic conditions is increasing globally, particularly among older people.Reference White, Issac and Kamoun 10 Chronic conditions exacerbate vulnerability during disasters.Reference Benevolenza and DeRigne 11 , Reference Evans 12 Physical or mental decline and increased health-care demands, issues with mobility or isolation, and less access to social, informational, and financial resources can heighten the impacts of disasters on the well-being of older people and their capacity to respond to and recover from disaster events.Reference Daddoust, Khankeh and Ebadi 13 Natural hazards, such as bushfires, can impact both physical and social environments, disrupting health services in various ways, including damage to infrastructure, displacement of communities, disruption to activities of daily living, and reduced availability of health professionals.

Natural hazard events and public health emergencies place greater demands on the need for self-management of health conditions, often supported by primary care services. In these circumstances, access to primary care is particularly important for those with chronic conditions. Vulnerabilities arise when older people have reduced functional capacity to care for themselves, where, for example, this is exacerbated by sensory impairments such as reduced hearing and vision and limitations in mobility.Reference Daddoust, Khankeh and Ebadi 13 It is therefore important to better understand how older people with chronic conditions engage in self-care to manage their health and well-being in the context of intersecting public health and environmental hazards.

Methods

This article aims to explore how older people maintained their health and managed chronic conditions during the 2019-2020 bushfires, floods, and COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Data were collected as the first phase of a sequential exploratory mixed-methods project. The larger project included both semi-structured interviews and a cross-sectional survey with older Australians to explore their experiences of self-care during disasters. Given the large volume of data and disparate aims, this article reports only the interview component. Survey data are published separately.Reference Halcomb, Thompson, Morris, James, Dilworth, Haynes and Batterham 14

Participants

People aged over 65 years and living in the target region were invited to participate through multiple strategies. First, study information was disseminated to over 170 local community groups and organizations. Additionally, letterbox drops, social media (e.g., Facebook), and local print and radio media were used to recruit participants. People interested in participating contacted the researchers, who provided study information and scheduled an interview with those willing to participate. Interview participants were recruited until data saturation was achieved and no new information was emerging from subsequent interviews.

Data Collection

Two researchers with expertise in interviewing conducted semi-structured individual interviews via videoconferencing. Interviewers explained the study and sought informed consent, explaining that participants could stop the interview at any time if they wished. Questions were developed by experts in primary care, older people, disasters, and qualitative research. All interviews were conducted in English and audio-recorded. Interviews were undertaken between March and December 2021 and lasted between 30 and 93 minutes (mean 51 minutes). After each interview, the interviewer made field notes.

Data Analysis

Audio-recordings were transcribed by an external transcription service. Completed transcripts were cross-checked against the recordings to ensure accuracy. Transcripts were then uploaded to NVivo v.12 15 and were subject to close reading to allow for general inductive thematic coding.Reference Braun and Clarke 16 Transcripts were coded by one team member (TD), and the emergent codes were independently checked by two others (CT and SJ). A selection of transcripts were cross-coded to ensure the robustness of the process. Team meetings were held to collectively discuss codes and consider key themes and allow for data comparison.

Results

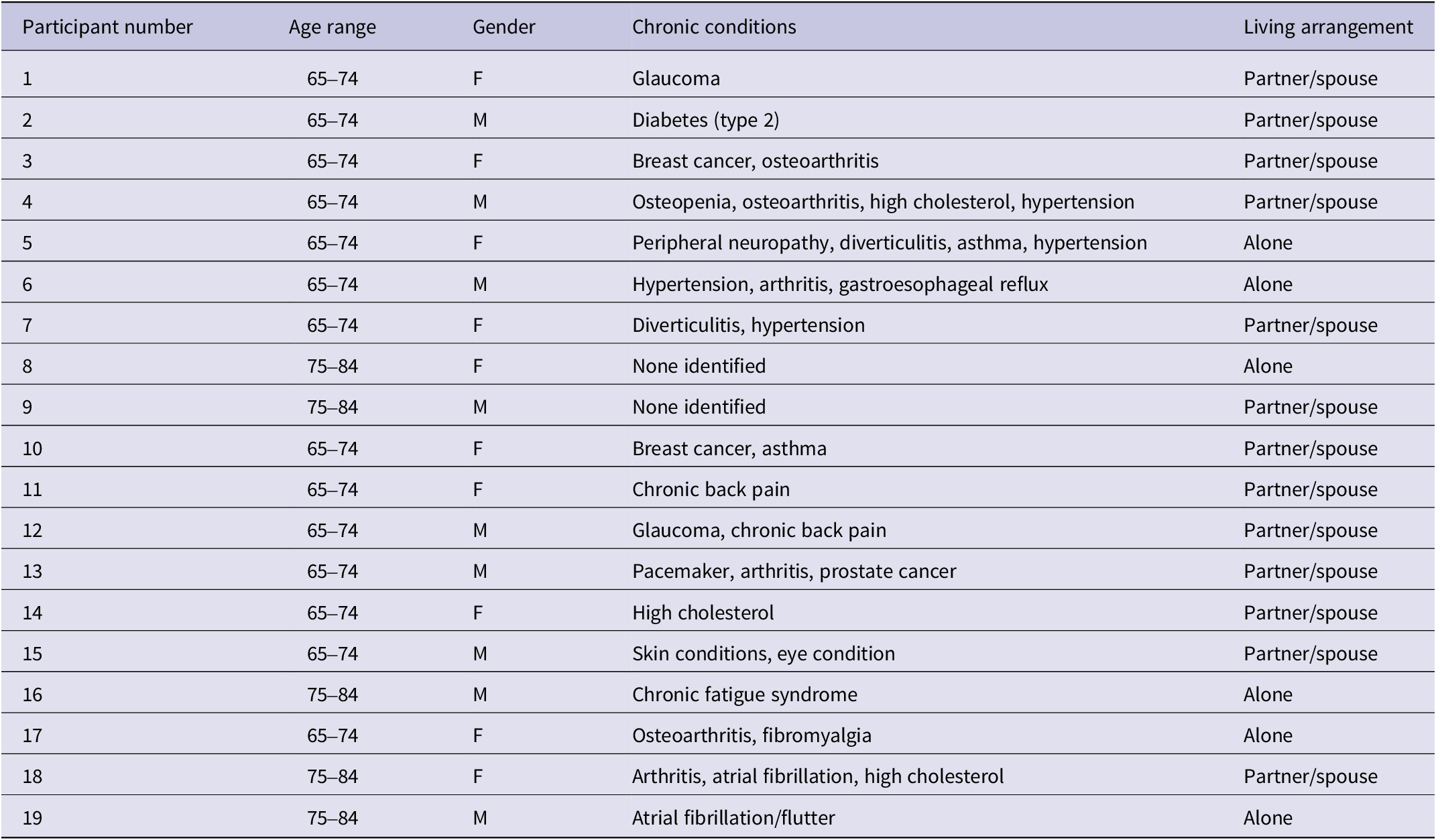

Of the 19 participants, 74% (n=14) were aged between 65 and 74 years (Table 1). Thirteen participants (68.4%) lived with a partner/spouse, and six (31.6%) lived alone.

Table 1. Participant demographics

Three themes were identified related to participants’ experiences—namely, key challenges to managing health and self-care, strategies for staying healthy, and the compounding nature of the disasters. These are discussed in more detail, including their subthemes, below.

Key Challenges to Managing Health and Self-Care

The bushfires and pandemic presented various challenges to managing health and self-care. The extended nature of both events is especially notable in relation to the difficulties experienced. “It [the bushfires] just kept going for months and months and months” (P15).

Disruption to daily activities and social networks

Significant bushfire smoke led to public health recommendations to stay indoors. Concerns about smoke exposure reduced outdoor activities. Some participants ultimately relocated for periods to escape the persistent smoke.

In January 2020 we did not see blue sky until the 31st of January… I couldn’t go out…we closed every window and door in the house for probably a month because it was disastrous to go outside. It was disgusting… (P10)

We actually left for Canberra, because, by then, we had pretty severe smoke inhalation. (P4)

I was sick of the smoke here; I’d breathed so much of it. So, I went to an old haunt of mine… (P16)

The bushfires also disrupted participants’ daily self-care practices, including having to redirect time and effort to preparing for and responding to the fires and loss of local amenities, and even prompting dietary changes. One participant, whose diet was important to the management of her condition, shared how stress and conserving water for firefighting impacted her diet:

The [condition] is something I’ve had for a very long time and is definitely stress-related… when you’re stressed you tend not to eat as well…And our veggie patch of course was out of action… we were conserving water because we kind of were already feeling quite threatened by fire… we didn’t have that extra really fresh stuff that we were generally used to. (P7)

Similarly, COVID-19 disrupted routines and social networks due to social distancing, lockdowns, and exposure fears. Pandemic restrictions prevented participants from engaging in various self-care practices, halted communal gatherings, and restricted access to community spaces.

We haven’t been able to have any community meetings, which has been difficult… (P1)

It was quite a scary time as it meant that people were actually not going out, that became fairly disruptive for a lot of our activities and meetings. (P13)

Although a few participants felt that “it hasn’t really changed our daily lives that much” (P7), most described a profound impact on their social life and well-being. Participants who lived alone felt the loss of social connection and resulting isolation particularly keenly.

I’m really isolated actually… COVID has completely closed my life down. My social life… it’s depended on ringing one of my friends, somebody I know, and then going out for lunch with them or going for a cup of coffee… All that has stopped because everything closed down… now I have very little contact with people outside my home. (P5)

I was exhausted, emotionally, mentally, physically. We couldn’t do any of the things we normally did… I belong to our local walking group, but I haven’t done that since COVID started, so that’s 18 months and I miss it like anything. (P10)

Distress was also caused by being physically separated from family.

Getting contact with our family directly is probably more the biggest disruption and the biggest angst…especially not seeing our grandchildren growing up… my wife is very anxious and upset about not seeing the grandchildren. (P13)

When COVID hit my mum was still with us then and she was in a nursing home, so we couldn’t go and visit… our sons… they’ve both got families and, you know, they’ve got children, we haven’t had the same interaction with them… it’s a lack of face-to-face interaction with family that I’ve really felt. (P14)

Although much of the pandemic social restrictions were enforced by government public health mandates, some participants also restricted social contact themselves because of exposure concerns. They discussed grappling with the tension between the desire for social connection and the risks to themselves.

I’ve really missed my kids and my grandkids and that’s made me feel really awful and teary at times and I feel really torn, because I want to see them more and I know that there’s a risk there in doing that… I feel completely conflicted about what to do. (P1)

Some participants described that fear and anxiety were amplified by health messaging that identified older people, particularly those with chronic conditions, were especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

I didn’t want to be amongst people because the pandemic. did worry me… when it first happened it was very much an alert for older people, so I was absolutely terrified that something would happen to us. (P18)

All the stuff is that we’re older people and that we’re completely at risk. And so, if we get it, it’s not like a young person getting it. For us, it’s almost like a death sentence and that makes it really hard, all that health messaging around it that if we get it, we’re basically gone. (P1)

Delayed treatment and disruption to health services

Delaying treatment or routine care and disruptions to health service access were experienced by participants across the disaster events. Preparing for and responding to bushfires consumed time and energy, meaning that some participants failed to seek treatment or delayed procedures.

I did have a problem during the fires… it was kind of a gynae type of issue, and I delayed going to see the doctor… because I just didn’t have time to care for myself. (P1)

Participants also experienced health service disruptions due to the widespread bushfire impacts, with fires, smoke, and mass evacuations resulting in road closures and long traffic delays.

…because of all the traffic jams everywhere in the blaze… The biggest concern for me personally of course, was my access to Canberra, because the bushfire started just when I started my chemo… between Canberra and here, less than two hours sometimes, suddenly became a trek… our longest trip was one day to go up and down for chemo… was a 16-hour trip. Other ones were about 10 to 12 hours on average… because of delays along the way, because of fires… traffic. (P3)

Following the pandemic outbreak, some participants delayed treatment due to fear of exposure.

I just couldn’t overcome the fear of going into a waiting room versus the fear of… deterioration of my eye condition… I was just sitting there all the time sort of thinking, “You know, I really need to do something about this, but I can’t”… I’m thinking, “Oh my god, I’m going to lose my sight, but I can’t go to the COVID thing”… the fear of going out and sitting in a waiting room just far outweighed sore eyes. So I just put up with it. I just put up with the pain. (P1)

Participants described having to “postpone my appointments several times because of the outburst of infections in the Sydney region” (P2) or having to “change a couple of appointments last year during lockdown situations” (P1). Others spoke of “not being able to visit in person the exercise physiologist. Having to rely on phone calls and chats… it’s a bit of a barrier” (P3).

Exacerbation of health issues and emergence of new health challenges

The stresses and demands of the disaster events led some participants to experience exacerbation of chronic conditions and emergence of new health challenges. Participants reflected on how the anxiety and fear of waiting for the fires to impact them, preparing/defending homes, or evacuating (sometimes multiple times) and dealing with devastation and loss were all physically and mentally taxing:

I felt very alone in carrying the burden of preparing for the fire. I got the worst chronic nerve pain and muscle stiffness; I was fatigued beyond belief. (P17)

Before the fires, I’d had shingles – bad shingles – and that came back… it took its toll; stress, stress, stress all the way. (P18)

The physical stresses of dealing with the bushfires and impacts on local amenities also resulted in new health challenges.

I should’ve followed my wife’s instruction and had a rest… I didn’t… I ended up with sciatic nerve problems… which was really debilitating and ended up in hospital. (P13)

[W]e were… moving stuff in the car to put down by the seashore, and I fell down the steps and broke my ankle. (P15)

…my health has deteriorated, my physical health because I’m not doing that regular yoga practice… I am noticing more sort of arthritis in fingers and that kind of thing which I’ve never really worried about before. (P7)

Impacts on health extended beyond the bushfire, with participants discussing the challenges of the recovery, including ongoing respiratory issues, sleep disturbance, and mental health issues. There was also concern about the significant smoke inhalation impacting their ongoing health.

The smoke… I coughed for a full 14 months afterwards; every morning I would wake up with this smoker’s cough… After the fires, I went down a black hole and I took a very small dosage of antidepressant for a while… for the first seven or eight months, I’d wake up every morning and I’d just cry. (P17)

My sleep’s not great, actually, that’s probably deteriorated a bit over the last several months… I think partly the, partly it’s sort of the pressure… (P12)

In relation to COVID-19, participants discussed how fear, anxiety, and social isolation impacted their mental health.

With COVID, you can’t see who’s got it, so you have to be suspicious of everybody… I don’t know how you take the fear or the distrust of people away… I think fear is bad for people’s mental health. (P10)

For some, the stresses of COVID-19 compounded the bushfire impacts, with this cumulative adversity further impacting mental well-being.

I think everybody who’s been through this experience… is not where they were before all of this… we talk a lot about bushfire brain. Now people talk about COVID brain; we’ve got bushfire and COVID brain… people who haven’t lived through it probably don’t really recognize the depth of the impact of all of this and the depth of the trauma. When we get together, and I can feel it coming on now, we often just end up weeping. (P7)

Strategies for Staying Healthy

Participants described a) drawing on community, social connections, and meaningful relationships and b) maintaining a sense of normalcy through routine, healthy habits, and enjoyable activities as key strategies for coping and maintaining health.

Drawing on community, social connections, and meaningful relationships

Drawing on community support, social connections, and meaningful relationships was seen as an important coping strategy. During the bushfires, community connectedness was especially significant for supporting mental health and dealing with the trauma. Participants described how local communities “pulled together like I’ve never seen it before” (P13). “It was beautiful the way people came together … I felt myself less isolated in that period because we all gathered around this common catastrophe that we’d shared” (P9). Some even suggested that they had built and strengthened social connections and felt stronger ties to the community because of their experience.

People came and helped us who we didn’t know, and then some other people who knew us then found places… Even now, I feel teary about it. I’ve never ever experienced anything like the outpouring of support that we got. (P1)

Participants identified examples of informal community support networks drawn on during COVID-19. These included younger people volunteering to collect packages from the post office or deliver medications for those trying to limit interactions. Where in-person social interactions were restricted, many participants shifted socializing online, which created new opportunities for connection.

Zoom has been fantastic and we’ve done an awful lot on Zoom… in some ways I feel more connected than ever because of Zoom. (P7)

One of the nicest things about COVID and the restrictions is that instead of texting one another, I notice we phone another… before the COVID lockdown, it would have been a little text message… now we actually phone and have a chat. (P17)

I’ve learned about Zoom which I didn’t know before. It’s a great way of connection… I was doing my ukulele classes online… I was doing morning prayer with my former church online. In fact that’s been sort of quite a lifesaver… probably the biggest thing is the social contact. (P8)

Maintaining sense of normalcy

Another key strategy for managing both health and well-being was maintaining a routine. For some, the routine was about maintaining basic daily activities:

If I feel good in myself, then it makes me physically feel better… Just things like doing makeup every day, looking after my skin, making sure I’m dressed properly every day… So routine I suppose, of getting up, having a shower, getting dressed, making the bed… (P3)

Worst-case scenario, you get up and if things are really bad, clean the bloody bathroom, clean the stove; do something practical… You do not stay in your pyjamas; you do not stay in bed… No matter what you feel – even if you just want to crawl under the covers, put the pillow over your head, and not come out for a year… you have a shower, and you put your clothes on, you put one step in front of the other, you vacuum the floors, and then you can turn around and say, “Oh well, it’s better than it was this morning.” (P17)

For others, it was about continuing to do activities that gave them purpose or a sense of achievement to shift the focus away from the disaster and reduce the mental health impacts.

We’re planning on a slow trip up the coast back to Brisbane… that gives us a goal to work towards, which I think is good… (P4)

I try and have a bit of a routine on a regular daily basis… I’m quite good at inventing projects to keep myself busy. (P15)

I started writing; I’ve started writing crime novels. [Laughs] And it’s great… it’s been great; it’s cathartic. (P16)

Although outdoor recreation during the bushfires was severely limited by the heat and smoke, during COVID-19, participants described getting outdoors for leisure/exercise. While restrictions prohibited group activities, participants were able to get out alone or with household members. The proximity of easily accessible and relatively remote areas to enjoy nature in the region may have positively contributed to this.

I walk for an hour every day in the forest, which is only five houses away from my place and the mountain bike tracks. So I haven’t stopped that… being able to go out walking in it’s been really important, you know just getting out in the fresh air. (P8)

So I have decided that, OK, I’m staying at home, but there is a 10-km radius for exercise, so yesterday afternoon, for instance, I went for an hour and a quarter bush walk… you become quite resourceful into how you can actually keep on exercising or keep active. (P14)

Across disaster contexts, meaningful social connections and relationships that were important to participants’ well-being extended to animal companionship. Pets provided an important source of connection and emotional support. “Get a dog… they’re wonderful” (P16). Having pets was important in supporting participants to maintain a routine and encourage regular physical activity.

My chooks help keep me healthy. I go out – I have to go out at least three or four times a day. I’ve got a lot of chook pens. I walk around a lot. I breathe the fresh air. (P1)

I’ve got a dog now, I force me self [sic] to take him for walks, and that helps too. (P16)

Compounding Nature of the Disasters

Participants highlighted various interactions between the bushfires and COVID-19. The overlapping nature of the disasters meant that it was difficult for some to separate the events, with many describing it more as an extended period of adversity. Some participants, however, reflected on how “communities have not been able to have the type of community consultation that you would really like to have post bushfires. So it’s meant that a lot of conversations which would have been very necessary to have post bushfires within your community have not really been able to take place because of the restrictions imposed by COVID” (P7). Another participant described how what they have “missed is the ability just to sit with people and share… what happened was that we collectively experienced this together, and so, there’s a whole thing around, for me, about how – like after the fires I wanted to have something where there was a kind of celebration plus a recognition and a space for people to say like ‘We got through this,’ and lots of people didn’t…’ We haven’t had any – because of COVID” (P1).

Some participants felt that the pandemic response also undermined the community connectedness and social capital that had been established during the bushfires.

…in the fires we had this sort of… people were hugging each other, and people were together and they were supporting each other and nobody had a worry about taking you into their house and then you get COVID which is exactly the opposite. Nobody wants to hug you [laughs] and nobody wants to take you into their house. So it’s been really tricky, that kind of swing between the two things and I found that quite difficult. (P1)

Beyond these compounding impacts, the successive nature of the disasters allowed for adaptive learning from the bushfires to be used to help manage well-being during COVID-19.

One of things that happened is that the fires, the kind of emotional learning that we had during the fires really helped us with COVID… what happened was that we were kind of well prepared for COVID. (P1)

When you’ve been through what is one of the worst experiences in your life, anything else after that doesn’t seem so dramatic and terrible… And the other thing that I’ve become aware of is that we recognize we’re older and we recognize that it’s OK to ask for help… we are aware that we will need some help, and we are looking at it, which I don’t think before the fire we would have. (P18)

Limitations

As a qualitative study, this investigation reported the experiences of a subset of survey respondents to more deeply explore their experiences of the disasters. Given the risks of COVID-19, interviews were conducted virtually, which may have limited rapport and diminished visual cues for the interviewer. The setting was chosen due to its significant bushfire impacts; however, public health restrictions varied markedly across the region during the pandemic. Participants’ experiences of COVID-19 may have been shaped by a relative sense of safety living outside of major urban transmission sites. Most participants were living independently, and so their experiences may have differed from those highly reliant on health and social services. Although the research sought to focus on the social and external factors impacting experiences of the fires and pandemic, various internal psychological factors such as values, beliefs, and personal dispositions not explored in this study may also shape the disaster experiences of older people and warrant further examination.

Discussion

This study has given voice to participants’ experiences during successive unprecedented disasters and highlights how these impacted self-management and well-being among older people. Data identify the key challenges faced and the strategies used to maintain physical and mental health and manage chronic conditions. The study provides unique insight into the compounding effects of successive disasters, as well as the differing impacts due to the specific nature of the disaster. The findings emphasize the importance of both personal and community contexts and highlight key supportive strategies.

Relational-social factors are key external coping factors that support chronic condition management.Reference White, Issac and Kamoun 10 The value of strong and meaningful social connections as a protective factor and coping mechanism was especially evident in this study, adding further support for work stressing the significance of social resources for disaster resilience and recovery among older people. This resonates with the literature highlighting the importance of social capital,Reference Brockie and Miller 17 relationship status,Reference Van Beek and Patulny 18 and neighborhood tiesReference Sasaki, Tsuji and Koyama 19 in optimizing mental health. In our study and in the wider literature,Reference Harms, Abotomey and Rose 20 , Reference Williamson, Banwell and Calear 21 the bushfires drew communities together, forming a source of support. This was juxtaposed with the social distancing around COVID-19 that caused communities to drift apart. Social distancing restrictions during COVID-19 meant that technology was heavily relied on for building and maintaining social connections. The findings highlight the importance of supporting digital literacy for older people, particularly as digital technologies are increasingly used for both disaster management and health interventions.Reference James, Ashley and Williams 22

Finally, the successive nature of the disasters resulted in both cumulative adversity and opportunities for adaptive experiential learning. This illustrates that successive disasters cannot be treated as discrete events. Delays and disruptions to self-care and therapeutic interventions can have significant implications for older people, contributing to delays in diagnosis and treatment, worsening health status and increasing mortality.Reference Baum, Barnett and Wisnivesky 23 , Reference Dosa, Feng and Hyer 24 Putting personal health needs aside during disaster eventsReference Owens and Martsolf 25 becomes a particular risk in the context of prolonged, successive disasters. However, alongside the difficulties of compounding impacts, successive disaster events can offer scope to capitalize on learning and resilience building for both individuals and communities. Research following the recent multiple flooding events in Eastern Australia demonstrated the considerable benefits of community connections and social capital for resilience in communities that have now been hit by bushfires, COVID-19, and successive destructive flood events.Reference Taylor, Miller and Johnston 26 Communities with strong connections and support have fared better overall, with community-led initiatives often proving most effective and popular. However, it is unclear how long community-led initiatives, connections, and networks can effectively support communities during prolonged and compounding disaster events.Reference Taylor, Miller and Johnston 26

Conclusion

A deeper understanding of older people’s experiences of managing self-care during successive and compounding disasters is critical for developing interventions and support strategies that are targeted to their specific needs. This study highlights the importance of social connectedness and routine as key strategies employed in managing health and well-being. The findings are useful in identifying and affirming broad principles to help support older people, particularly those managing chronic conditions, during disasters. Findings can also inform future policymaking and health service planning and guide interventions and health care for older people with chronic conditions.

Data availability statement

Identifiable data are unavailable. Ethical approval for use relates only to the research team.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the University of Wollongong Global Challenges Program.

Competing interests

None declared

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Number 2020/413). Informed consent was recorded for all participants.