Exposure to nuclear radiation is a major public health concern following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. Fortunately, exposure levels have not posed health risks to the general public in the affected areas. 1 However, the local super-aged population where almost 1-in-3 were over the age of 65, remains the hardest hit. Reference Morita2 A range of social, economic, and public health consequences has arisen, including an increase in mortality among elderly people, during evacuation and among those placed in temporary housing, coupled with an increased risk of diseases and mental health issues. Lack of access to health care worsened the impact of relocation, ruptured social links, loss of homes and jobs, disrupted family ties, and stigmatization. Many of the local youth had already emigrated in search of a better life, weakening traditional family support systems. Reference Ishikawa, Kanazawa, Morimoto and Takahashi3 This highlighted the aging problems in Japan’s urban communities where traditional social systems are fast disappearing, emphasizing the growing social isolation of the elderly. Social networks, encompassing several generations within families and communities, used to be a core support mechanism. However, Japanese elderly are now more socially isolated than in other industrialized nations. Reference Muramatsu and Akiyama4

Soma City, located 40–50 km from the nuclear power plant, has an aging rate of 29.5%, one of the highest in Japan. Approximately 10% of households are categorized as elderly, within which 804 individuals live alone. Social isolation of the elderly increases the need for nursing care, and public expenditure per older person in neighboring Minami-Soma City after the disaster increased by 30%. Reference Morita, Leppold and Tsubokura5 Thus, it is of paramount importance to devise and implement effective initiatives to prevent isolation of the elderly in disaster situations. Here, we illustrate 2 successful endeavors undertaken in Soma City.

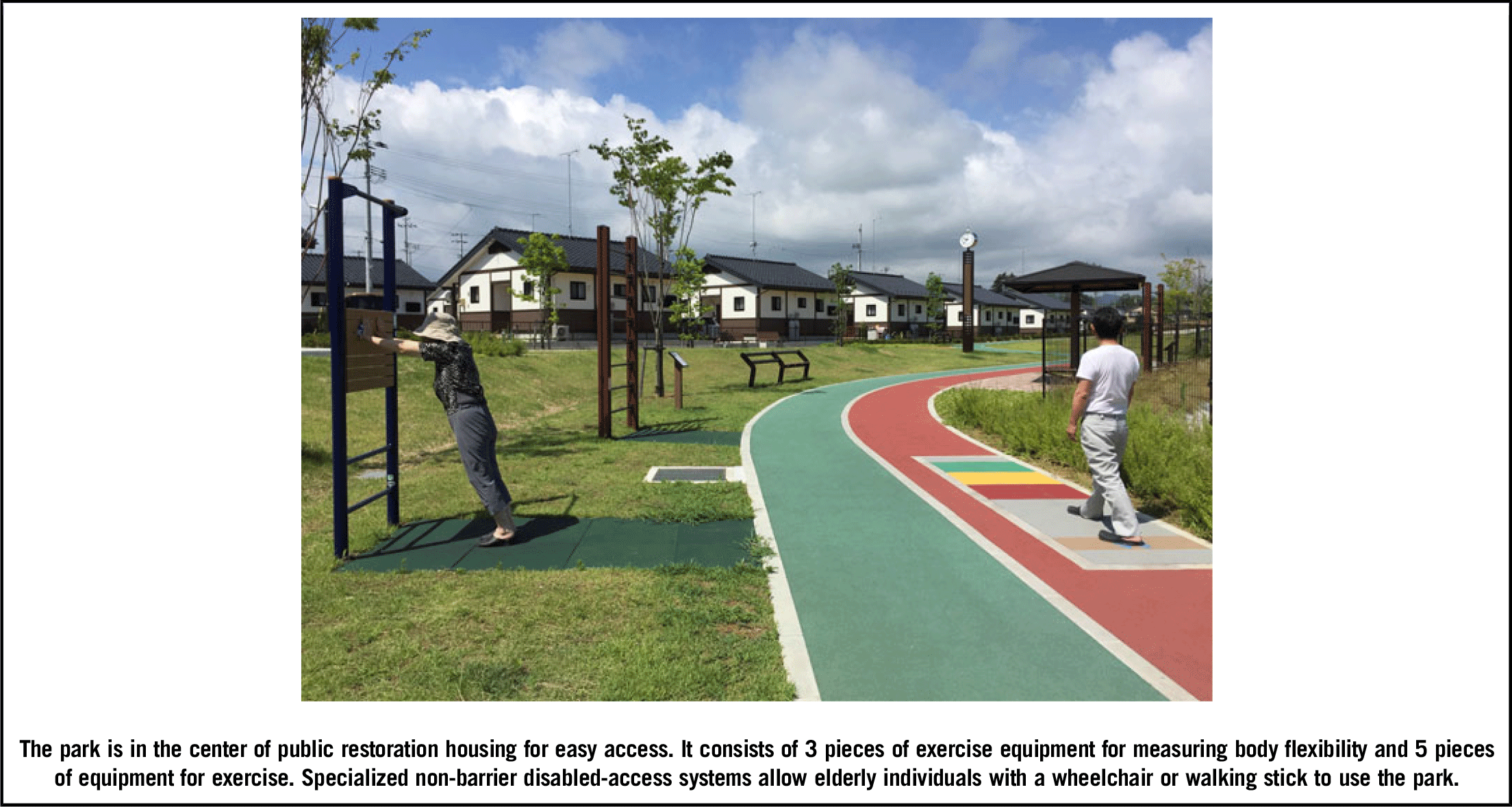

Japan’s public health interventions have historically been holistic, community-driven enterprises, involving multidisciplinary doctors, local governments, industry and funders, cohesively working to meet the needs as identified by local communities. Exploiting this mechanism, the Soma local government constructed Idobata-Nagaya (Figure 1), a communal living space where there is a shared laundry facility, a common room for meals, and residents can check on each other’s health and well-being. In 2017, there were 45 residents, over half of whom were over 80 years old. The government also built a park named Honebuto (meaning “bone-strength”) (Figure 2), designed to provide opportunities for exercise. Health promotion projects assessed the park’s impact, with 20 elderly individuals exercising twice a week. In 2016, 899 users participated and benefitted.

FIGURE 1 Lunch at Idobata-Nagaya

FIGURE 2 Honebuto Park

Clearly, differing populations in Fukushima need differing kinds of health care. Isolation of the elderly can be caused or exacerbated by any disaster. Central and local authority responses are often initiatives for local residents rather than with them. Responses such as Idobata-Nagaya and Honebuto, where local government orchestrated commitments and inputs from multiple stakeholders, help prevent isolation of the elderly and improve their health and welfare. Such efforts can help empower community representatives to fully understand their own situation and decide on appropriate actions that can help rebuild their shattered communities in partnership with all.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Andy Crump for his kind support and careful proofreading of the study manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.