National security special events (NSSEs)1 occur frequently in the United States. Preparedness activities surrounding these events and their impact on the local health care infrastructure have not been well described. This article describes the impact of the NSSE-designated 2008 Republican National Convention (RNC) on the City of St Paul and the surrounding metropolitan area including the following:

• Preparedness activities of health and medical stakeholders

• Impact on the local health care system (including key local hospitals)

• Operational challenges

• Identified successes and areas for improvement

METHODS

Descriptive and narrative information were provided from the authors' institutions and personal experience during planning and event operations. The following data were collected:

• Hospital bed availability data from daily data collected on MNTrac Web-based system

• Data from the 3 St Paul hospitals closest to the Xcel Center (United, St Joseph's, and Regions) and the Minneapolis downtown level 1 trauma center (Hennepin County Medical Center [HCMC]) reported from September 1–4 reflecting:

1. Daily emergency department [ED] volume (and average daily ED volume for comparison)

2. RNC-related ED visits

3. Daily elective procedures performed (and average daily elective procedure volume for comparison)

• Emergency medical services (EMS) hospital diversions during the RNC collected from the Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) MNTrac Web-based hospital diversion–incident management system

• EMS run volumes for St Paul Fire (St Paul) and HCMC EMS (downtown Minneapolis) compared with daily average volume

• Weather data for September 1 through 4 from National Weather Service reports

• Numbers of protestors and arrests from police and emergency management estimates and media reports

• Protestor treatment information from “street medics” and a designated protestor clinic,

• Medical encounters from National Disaster Medical System (NDMS) data and Regions hospital staff at:

1. Federally staffed medical evaluation points at county correctional facilities and near protest areas

2. Xcel Center first aid room

All data collection at hospital facilities was approved by the respective institutional review boards. Given that these data were being collected for RNC-reporting purposes and did not involve patient identifiers, the study was approved as “exempt” at each facility. Descriptive statistics were used.

RESULTS

System Description

St Paul, MN, has a census population of 277,251.2 EMS services within the city are provided by the St Paul Fire Department (SPFD), which responded to 27,457 medical calls in 2007.3

The total population of the metropolitan area of St Paul and Minneapolis is 3,208,012, encompassing multiple counties and jurisdictions.4 Twenty-nine EMS agencies staff 220 ambulances. The EMS agencies have mutual aid agreements and are represented by the Metropolitan Emergency Medical Services Board (MESB). Twenty-nine hospitals with approximately 5000 operating acute care beds are organized for disasters under the Metropolitan Hospital Compact (MHC). HCMC is a 415-bed level 1 trauma center in Minneapolis and is the regional hospital resource center (RHRC), a coordination point for hospital preparedness and response. Nine city and county health departments and the Minnesota Department of Health are responsible for disease prevention, surveillance, and investigation activities.

Republican National Convention

The Xcel Center, the location of the 2008 RNC, is a 30,000-seat arena connected to an adjacent convention center. The US Secret Service (USSS) assigned a full-time coordinator for the RNC in February 2007, who cochaired the executive steering committee with an assistant police chief from the City of St Paul (SPPD) and oversaw 17 subcommittees. These subcommittees are generally the same for all NSSEs.

The RNC took place September 1 through 4, 2008, and attracted approximately 100,000 visitors to the metropolitan area. Delegates, guests, and media stayed in more than 100 hotels across the metropolitan area and were bused to the Xcel Center daily. Parties, functions, and demonstrations were held in multiple jurisdictions.

Primary concerns in addition to the usual mass casualty and weather-related events were terrorist and anarchist activities. Large antiwar protests were scheduled—anticipating up to 50,000 marchers—and an anarchist group called the “RNC Welcoming Committee” planned disruptive activities. Local law enforcement was able to infiltrate that organization, facilitating preemptive raids and arrests before the RNC.5

Planning and Interface With Federal and Other Agencies

The fire, life safety, hazardous materials, and consequence management subcommittees began meeting in spring 2007 and involved EMS, public health, and hospital representatives assigned by the USSS and SPPD. Response planning for the Xcel Center was coordinated by SPFD. Resource allocations were reviewed and vetted with USSS. USSS personnel made it clear at the outset that their commitment was only to support responses to the venue itself, and that planning and resources needed outside the venue (hospitals, public health, food safety, EMS, other cities) would not be included in the USSS process or expenditures.

The city of St Paul determined that USSS and the city would be responsible for requesting health and human services (HHS) assets deployed for venue support, including Urban Search and Rescue and Chemical and Biologic Incident Response Force (CBIRF).6, 7 MDH took responsibility for HHS and Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) assets8, 9 requested for events surrounding the RNC but outside of the city requests (Table 1).

TABLE 1 Federal Personnel and Assets Deployed in Support of Health and Medical Missions

Prehospital Resources for the RNC

Xcel Center medical services were provided at an expanded first aid room (Xcel Health Care Center). The area was equipped for major emergencies, including the ability to provide advanced care in place if safe transport was not possible due to protest activities. During peak convention hours there were 2 emergency physicians, 2 midlevel providers, and 4 nurses. Nine 2-paramedic teams provided response to the convention floor. Noncritical EMS transports from the Xcel Center were taken by a modified all-terrain vehicle or by 1 of 2 ambulances stationed within 50 ft of the first aid room to an EMS unit outside the perimeter fencing and handed off for transport. Critical patients would have been taken directly to the hospital by 1 of the 2 staged ambulances.

Two additional ambulances were kept in the restricted vehicle area (RVA) along with a first-alarm fire assignment and additional federal assets. These assets were based in a parking ramp 2 blocks west of the Xcel Center. CBIRF was deployed at 2 locations within the RVA to provide initial patient rescue and decontamination in case of an unconventional mass casualty event (MCI). Vehicles were not allowed to leave the RVA during the week of the RNC aside from EMS units transporting critical patients. EMS service to the city was augmented with 2 additional EMS units. Twenty-five mark 1 nerve agent antidote kits (Meridian Medical, Bristol, TN) and hydroxocobalamin cyanide antidote kits (Dey Pharmaceuticals, Napa, CA) were carried on each ambulance.

A mobile medical unit (MMU, an 8-bed acute care platform owned and operated by MDH) and a disaster medical assistance team (DMAT, from HHS) were located about 10 blocks from the Xcel Center–adjacent fire department headquarters and a law enforcement staging area to provide routine minor medical care, and a base of triage and casualty staging in case of an MCI. These assets were initially to be located closer to the venue but were moved back due to security concerns expressed by the USSS and SPPD. DMAT strike teams were located at 3 fire stations, a federal agency staging and coordination site, and in support of the CBIRF teams (Table 1).

Paramedics were also embedded in the ≥80-person law enforcement mobile field forces (MFFs) for medical support during crowd control activities. Officers with minor injuries could also seek care at the MMU location or in Minneapolis with medical providers at the law enforcement staging site.

The Northstar Health Collective, an umbrella group for protestor medical assistance,10 set up a free clinic across the street from Regions Hospital in a church basement. Decontamination, medical assessments, and psychological screening were available at this location. “Street medics” (medical training varied widely but at least 3 days were required) were equipped with basic first aid and a variety of riot-control agent–neutralizing solutions. These people provided assistance to many protestors, especially those affected by riot-control agents.

Regionally, EMS services increased staffing and available units (eg, maintaining old units in the fleet after replacement units were received). Approximately 70 EMS units were estimated to be available within 2 to 4 hours based on a survey of surrounding EMS regions. Regional EMS coordination was through the Metropolitan Region EMS Coordination (MREMSC), which was also the organization point for ambulance strike teams. The ambulance strike teams comprised 5 advanced life support ambulances and a supervisor, and could be deployed for special circumstances or an MCI. Finally, 2 specialty MCI buses that carry 12 and 18 nonambulatory patients, respectively, were available.

Hospital Resources for the RNC

An initial planning meeting was held for all regional hospitals 1 year in advance of the RNC. Supplemental hospital radiation survey meters were purchased and additional supplies and training provided via federal preparedness grants. Hospitals were advised to conduct business as usual during the RNC but to be prepared for contingencies. All of the metropolitan area hospitals have decontamination equipment, personnel, and level C personal protective equipment.

A St Paul hospital planning group was formed about 6 months before the event as a workgroup of the fire, life safety, and hazardous materials subcommittee to facilitate city-specific planning. This group held planning meetings and also participated with regional hospitals as part of scheduled hospital compact and regionwide planning meetings.

The 3 closest hospitals requested DMAT personnel during the convention to provide triage assistance in case of an MCI due to the likelihood of rapid self-referral of a potentially overwhelming number of patients and the fact that staff could have difficulty reporting to their facilities during an incident due to road congestion and closure.

St Joseph's Hospital (258 beds) is the closest hospital to the venue, located 0.25 mi northwest of the Xcel Center and was located along routes frequently traveled by protestors to reach their “viewing area.” St Joseph's was provided a state decontamination trailer to augment their garage decontamination facilities and 2 CBIRF and 10 DMAT personnel. A command center was open throughout the RNC. Chemical event antidotes from the SNS were located in an adjacent parking ramp.

United (362 beds) and Children's (76 beds) hospitals are located 0.3 mi southwest of the Xcel Center. United's surface parking lot was the unloading site for delegate buses. United shares an emergency department entrance with Children's. United and its parent Allina Health Systems maintained a corporate command center during the RNC. Five CBIRF and 10 DMAT personnel were based at United. An auxiliary decontamination trailer and tenting augmented usual garage-based decontamination facilities. United hosted a local chempack (nerve agent antidote pack) onsite during the event.11

Regions Hospital (358 beds) is located 1.5 mi north of the Xcel Center. Regions is the designated level 1 trauma hospital for the St Paul area and has decontamination facilities capable of processing up to 100 patients per hour, and hosted a local chempack onsite during the event. Regions was supplemented by a 6-person DMAT team for triage assistance in case of an MCI.

Public Health Activities

The Minnesota Department of Health (MDH) conducted expanded epidemiological activities during the RNC to rapidly detect, investigate, and treat unusual illness manifestations or clusters (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Minnesota Department of Health epidemiological activities.

Metropolitan hospitals, the Xcel Health Care Center, and select large-volume urgent care clinics sent, called, or e-mailed summary information about RNC-associated patients twice daily to MDH. In addition, MDH epidemiologists went to hospital EDs in close proximity to the convention venue during the week of the convention to look at logs and review charts of patients possible infectious disease diagnoses. Facilities were asked to immediately report any food-related illness, bloody diarrhea, unusual rash, suspect bioterrorism syndrome, or unexplained critical illness or death.

MDH worked with the US Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Energy, the Radiologic Assistance Program, the National Guard Civil Support Team, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation on environmental monitoring and handling of provisional field detection of hazardous substances.

MDH, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, and the US Food and Drug Administration oversaw food and water safety issues during the convention in conjunction with local inspectors. MDH facilitated a 43-member multijurisdictional event committee that addressed food, beverage, and lodging issues more than 1 year before the RNC, training inspectors and facility/catering employees and developing a mutual-aid agreement to allow jurisdictional inspectors to work across the area during the RNC.

MDH personnel met with representatives of the Northstar Health Collective to ensure that protestors received information on food safety, drinking water safety, and hydration and heat-related issues, and established points of contact with the group in case a health-related incident occurred.

Coordination/Command Centers

Multiple coordination and command centers required EMS, public health, and hospital presence. SPFD staffed a dispatch center in the Xcel Center. A trailer served as the base of fire/EMS operations for the Xcel RVA.

St Paul police and fire, St Paul hospitals, the RHRC, regional EMS communications, HHS, and MDH staffed seats at a 114-person multiagency communication center (MACC) 24 hours per day. This was the primary site through which real-time event information was processed for communication to stakeholder agencies.

A health and medical joint operations center (HMJOC) at MDH with local public health agencies, MDH, and the RHRC coordinated health and medical issues among the MACC, state emergency operations center, and HHS incident response and coordination team (located 2 floors below). Epidemiological, environmental health, and clinical and laboratory monitoring information that came into MDH was processed, summarized, and distributed as needed. EMS coordinated activities via the MREMSC center in collaboration with the HMJOC. Daily incident action plans and situation reports were issued to stakeholders, ensuring a common operating picture.

Jurisdictional emergency operations centers were open in St Paul, Minneapolis, and Ramsey County. In addition, a multiagency coordination center for the west metropolitan cities and counties including Minneapolis was activated. Daily videoconferences were conducted among these entities.

Operational Experience

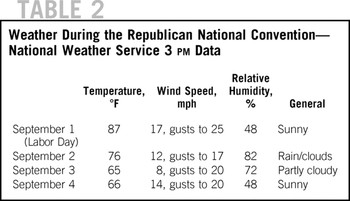

The RNC ran from September 1 through 4, 2008. Hurricane Gustav struck the Gulf Coast on September 1, causing that day's convention schedule to be reduced from 8 to 2 hours and dramatically affecting media coverage. A normal schedule was resumed the following day. Weather was seasonal in the area (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Weather During the Republican National Convention—National Weather Service 3 pm Data

A major march protesting the Iraq war attracted approximately 10,000 demonstrators on Labor Day, September 1. Along the route, splinter groups and anarchists broke away to shatter windows and challenge police lines. Protests and anarchist activities continued at a lower level throughout the convention with frequent skirmishes between their groups and law enforcement. A total of 818 arrests were made12; the most arrests made during a national political convention were 1806 in New York City during the 2004 RNC.13 Many of those arrested did not carry and would not provide identification, an issue that hospitals were prepared for, although none of these “unidentified” people required hospital treatment.

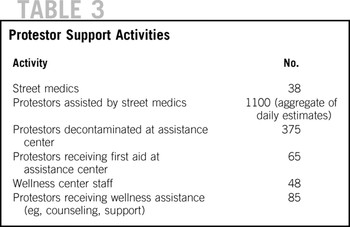

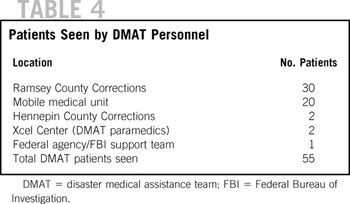

Street medics assisted many protestors suffering from riot-control agents (mainly oleoresin capsicum spray) exposure and other protestors sought care from the Northstar Collective (Table 3). A few heat exhaustion cases were evaluated. Some protestors were evaluated by DMAT team members at detainee processing points and the walk-in MMU location (Table 4), but none of the injuries was serious. Protestors presenting with fictitious symptoms (eg, chest pain) to avoid arrest or processing were not reported.

TABLE 3 Protestor Support Activities

TABLE 4 Patients Seen by DMAT Personnel

The Xcel Health Care Center evaluated 195 patients. Forty-six required work-up or intervention and 7 required EMS transport including cases of syncope, accidental cleaning chemical exposure, and neurological and respiratory symptoms. Two EMS transports to hospitals were made from the surrounding RVA. Most patient contacts were for blisters and superficial injuries.

DMAT operations were relatively uncomplicated, although the MMU location had to be evacuated (to the adjacent fire headquarters) on September 3 due to a nearby clash between protestors and police, and walk-in patients were not accepted on September 4 due to security concerns.

Security was a key operational issue. In addition to physical confrontations with police, protestors sprayed chemicals (dilute bleach) on a group of delegates, and a brick was thrown through a delegation bus window.Reference Kade, Brinsfield and Serino14 Police discovered and confiscated multiple caches of materials during the RNC including a stolen ambulance filled with lead pipes, wrist rockets, ball bearings, urine, feces, and other injuring and provoking devices. Regions, United, and St Joseph's implemented access controls (lockdown) for brief periods due to protest or other issues adjacent to their facilities. Demonstrations near St Joseph's presented issues for patient and EMS safety on 2 nights for brief periods, including a bomb squad call to check an abandoned backpack at the hospital entrance. Ventilation systems were briefly shut down 1 night to prevent smoke and riot-control agent from entering the hospital air supply. Usual vendors for St Joseph's (eg, blood suppliers) had to be escorted by strike team ambulances to the hospital for several hours due to crowd and traffic problems.

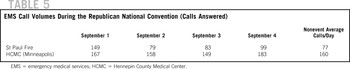

EMS run volumes were slightly above average in St Paul and below average in Minneapolis (Table 5), aside from high SPFD run volumes on September 1 coincident with warm weather and the largest protest march. Diversion events were minimal. St Joseph's closed to EMS due to a street protest 1 evening for 10 minutes and 1 hospital closed to EMS for 3.5 hours on September 1 due to an unrelated computer failure.

TABLE 5 EMS Call Volumes During the Republican National Convention (Calls Answered)

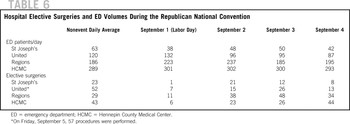

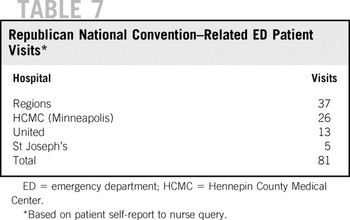

Elective surgery volumes were low, particularly at the closest hospitals (Table 6); however, Labor Day week tends to be a slower than normal week for surgeries and this may have had an effect as well. One surgical group cancelled procedures during the RNC due to anticipated traffic and parking issues. Patient and provider self-imposed curtailment of procedures and apparent decreases in ED volumes had significant implications for United and St Joseph's. United estimated lost revenue of $3.1 million dollars during the RNC compared with average surgical and ED volumes. The impact of the RNC on ED volumes was minimal despite the high hotel occupancy and many special events (Table 7), although nurse capture and patient self-report of affiliation with the event is likely imperfect.

TABLE 6 Hospital Elective Surgeries and ED Volumes During the Republican National Convention

TABLE 7 Republican National Convention–Related ED Patient Visits

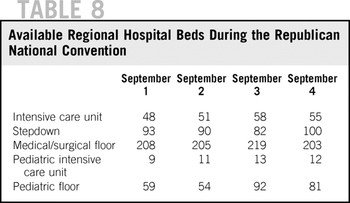

Available beds across the region were relatively stable, with approximately 10% of operating beds in each category available, with an increase to nearly 20% of pediatric beds available during the last 2 days of the RNC. Average occupancy based on prior regional exercises is 86% to 90% (Table 8).

TABLE 8 Available Regional Hospital Beds During the Republican National Convention

There were no epidemiological events noted. Most hospitals reported twice-daily data to MDH but variability in determining RNC-affiliated patients and in reporting presented difficulties in unifying the data.

Areas of Success

The information exchange among EMS, hospitals, and public safety/public health was excellent, with timely information flow facilitated by the MACC, Web-based systems, daily scheduled conference calls, and daily incident action plans. In past NSSEs, HHS has typically deployed full 35-person DMAT teams and set up bases of operations at secure locations for contingency responses. The use of smaller strike teams, some with daily responsibilities for patient care, was novel, and the experience was generally positive. Although they did not see many patients, the potential for the corrections facilities to have large numbers of people with real or fictitious complaints requiring medical evaluation was high. HHS is not allowed to treat inmates nor patients in law enforcement restraints including handcuffs; these issues were addressed in preplanning and were effectively managed. The strike teams enhanced the flexibility of response and could have been critical if massive protests, an MCI, or mass contamination incident had occurred.

Hospitals, public health agencies, and EMS treated the RNC as a full-scale functional exercise, and regional exercise grant funding supported MREMSC and the associated ambulance strike teams, which functioned well in their first deployment. The Minnesota MMU was used for the first time and DMAT team members working on the unit provided valuable feedback for operational refinements.

Coordination with protestor groups was important. The protestors and activists may be more likely than delegates or media to be at risk for foodborne and contagious illness due to their often unregulated living and eating conditions. They are also less likely to report their illnesses or seek treatment for injuries from usual sources of medical care. A highly organized local coalition was critical to meeting the needs of these individuals.

The HMJOC was the first use of unified command between state and local health departments and health care in Minnesota. Because public health is relatively new to incident command, it provided an excellent opportunity to train many new staff on software, use of incident command forms, the planning cycle, giving briefings, and preparing situation reports during a low-intensity event. Participants developed relationships with many new partners and were able to better understand the other agencies' resources and tools.

Areas for Improvement

Interactions between local and regional health and medical planners and the USSS and city of St Paul emergency management were somewhat contentious, generally due to the fact that USSS and the city were anticipating a law enforcement event and did not prioritize nor have background in medical contingency planning. Public health issues did not fit cleanly under the USSS fire, life safety, hazardous materials, or consequence management subcommittees. The authors suggest that for future NSSE events a health and medical subcommittee be established and be led by DHS or HHS medical preparedness staff and a local cochair with medical or public health background rather than by USSS field staff. Furthermore, there are no expectations from DHS or HHS for host community preparedness. Establishment of key benchmarks by DHS (eg, community capability to provide nerve agent antidote to 25% of attendees, decontamination for 25% of attendees within 4 hours) would greatly facilitate local planning and gap analysis and reduce conflicts about what constitutes “reasonable” preparedness.

St Paul received $50 million in special appropriation funding for the RNC. These funds were controlled by the St Paul Police Department. Thirty-four million dollars was budgeted to police overtime and hiring additional temporary officers. The rest was spent on other planning activities and supplies. EMS and public health received minimal to no funding for the RNC and had to take substantial staff time and supplies from their regular budgets. Some agencies creatively used exercise and grant funding from multiple sources to purchase equipment or provide services. Some EMS agencies held staff training during the evening hours of the convention dates to enhance the availability of responders at no additional cost to the agency. Public health was unable to obtain reimbursement for requested increased environmental sampling. The authors believe that future NSSE funding authorizations should include health and medical considerations, and that ideally the budgeting process should be overseen or reviewed by DHS or a third party appointed as part of the allocation process.

Security for HHS team members was a concern. The initial concept of operations for the MMU was that it would be protected adjacent to or inside the restricted area. Its location with the DMAT team tenting at fire headquarters was still somewhat vulnerable despite security fencing. Locating DMAT personnel close enough to the venue to provide triage and treatment support during an MCI but in a safe area is a delicate balance. Also, MCIs may occur at sites apart from the NSSE venue. Vehicle-based strike teams that can flexibly redeploy, provide minor care from a van or other vehicle platform, yet easily evacuate should the security situation deteriorate in their area may be preferred. Adequate security of medical, EMS, and fire personnel must be part of the planning process and properly funded.

Hospitals must have deliberate and phased plans for access control and have plans to communicate to EMS units and patients' safe egress routes; on several occasions there were safe exit routes, but some of the usual routes for patients and EMS were not easily accessible nor necessarily safe. Security officers with maps and good situational information posted at major facility exits may help address this need. In addition, although hospitals may request that ambulances divert to other facilities according to EMS policies in this area, there were no provisions for EMS to place a hospital on diversion due to events around the hospital. A new policy has been implemented to address this situation.

Credentialing for restricted areas was challenging, with few credentials available for medical personnel. Adequate credentialing of EMS, medical, and fire personnel must be planned for and given appropriate priority. Preplanning of credentials for federal personnel is also important. For example, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention personnel are required to stay with deployed SNS pharmaceuticals. Due to a misunderstanding with USSS, these personnel had not applied in advance for an RVA credential and USSS declined to issue them. Thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had to locate the antidotes 1 mi from the venue in a less secure location instead of within the perimeter fencing. Given that SNS assets are routinely deployed in support of NSSE, a process should be in place to address these issues.

Epidemiological data were variable. Some institutions relied on “hash mark” tracking, whereas others integrated tracking into electronic medical records and surveyed International Classification of Diseases codes for data. There was variable querying of patients presenting to determine whether they were affiliated with the RNC. Because of the small numbers of patients seen, it may not make sense to query the patients in this manner in future events. Reporting of gastrointestinal, respiratory, or other illnesses may have some value, but without baseline data this reporting may be difficult to interpret. There is a need for routine, automatic reporting of surveillance data based on electronic medical record queries to ensure good baseline data to allow interpretation of a possible event. The best epidemiological information likely comes from a heightened awareness of infection control and clinical practitioners for possible food-related and unusual illness patterns during these events.

CONCLUSIONS

Health and medical partners must address the basic medical needs of the community and visitors as well as protected person, dignitary, and detainee or prisoner needs in an extremely high-visibility environment during an NSSE. MCIs must be planned for and appropriate expenditures made to support a spectrum of response. Being underprepared and risking excess loss of life must be balanced with expending unwarranted time and funds preparing for low-risk, high-consequence incidents. Past use of health and medical resources is not a reasonable basis to predict future needs during these events due to this risk, but can help guide some overall planning. Our experience shows that this event added little additional patient volume to our system; however, the potential for the system to be overwhelmed was real and with higher heat indices, more violent protests, gastrointestinal illness outbreaks, MCIs, or major traffic disruptions the health care system could have been compromised. The authors believe that activities and planning surrounding the RNC significantly advanced the preparedness of the city of St Paul and the metropolitan area for all-hazards incidents that may occur in the future. Our experience and conclusions echo those from a recently published account of Boston's 2004 experience with the Democratic National Convention.Reference Kade, Brinsfield and Serino14 We recommend consideration of the following changes for future NSSEs:

Inclusion of health and medical requirements in initial budgeting and allocation of funding at the congressional and DHS level (eg, 10% of funding allocated to health and medical) and tracking of budgeting by DHS during the planning process

Establishment of benchmarks for patient treatment and decontamination for NSSE preparedness of which the host community is expected to be capable; this includes providing information on federal resources that can assist and the process for requesting their assistance

Establishment of a health and medical subcommittee under the executive committee to be cochaired by a DHS or HHS official and a local health and medical representative

Development of a health and medical playbook by DHS that incorporates considerations for planning, resource requests, deployment, and operations for NSSE to encourage consistency of preparation and provide a framework for the hosting community

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Josh Salzman of Regions Hospital for assistance with the Xcel Health Care Center and article data, and the innumerable personnel of the St Paul Fire Department, the metropolitan hospitals and participating clinics, MDH, local public health agencies, the Metropolitan Emergency Services Board, and our regional EMS agencies, who contributed to a safe and successful RNC and an outstanding systems training and assessment opportunity.

Authors' Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.