The COVID-19 pandemic in the United States has highlighted a divide between what public health leaders advise and what members of their communities choose to do.Reference Nan, Iles and Yang 1 Although slow or limited uptake of some public health recommendations may relate to limited information availability, other challenges may relate to specific communication strategies contributing to a breakdown in public health implementation. The variable uptake of evidence-informed measures in rural areas raises questions about how pandemic messaging has been received among local populations in these frequently under-resourced areas. Because successful adoption and/or adaptation of emerging pandemic surveillance and mitigation strategies requires not only local buy-in but also active participation from community partners, it is critical to build situational awareness of factors influencing sensemaking among potential partners in rural areas.

Growing interest in wastewater-based epidemiologyReference Cohen, Vikesland and Pruden 2 requires a better understanding of how local cultural and informational contexts may contribute to implementation challenges and opportunities. This study helps address this gap by examining perceptions of COVID-19 risk communication among rural Kentucky wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) operators, a community of practice whose collaboration is critical for successful SARS-CoV-2 wastewater surveillance.Reference Keck and Berry 3 Because the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Wastewater Surveillance System is operated on a volunteer-only basis, 4 understanding the perceptions of WWTP operators is vital to recruiting and retaining them as community partners.Reference Nghiem, Morgan, Donner and Short 5

To improve our situational awareness of potential communication and trust-related challenges during rural wastewater surveillance implementation, we asked operators about COVID-19 pandemic communication, analyzing responses using CDC’s Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) framework to understand how and why interview participants may have formed conclusions about official COVID-19 public health guidance. 6 The CERC framework delineates 6 foundational principles for officials to follow when communicating about high-stakes health risks. These principles are “Be First,” “Be Right,” “Be Credible,” “Express Empathy,” “Promote Action,” and “Show Respect.” They guide public health officials in developing and delivering messages to a variety of lay publics. 6

Methods

The University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (#64376). All participants provided written informed consent prior to their interviews.

The team used purposive sampling to select interview participants from 7 of 10 rural WWTPs providing samples for a wastewater surveillance study. We conducted interviews between October 2021 and February 2022. We conducted 2 interviews at 1 WWTP to ensure inclusion of a female operator; otherwise, we interviewed 1 operator at each facility. Leadership at 1 WWTP declined to have their personnel interviewed. One participant was interviewed twice due to a recording error; only the second interview was used in the dataset as it was nearly identical to the first but provided some additional insights valuable to understanding perceived trustworthiness of COVID-19 information.

Participating WWTPs serve rural, mountainous counties with populations ranging from ~14 000-48 000. These counties face socioeconomic disparities, with median household incomes and educational attainment at or below national and state averages. In addition, the region suffers health disparities across several dimensions that result in greater morbidity and mortality, as well as higher numbers of premature deaths, than national and state averages. 7

The interview protocol was developed by a team that included investigators with expertise in public health, community medicine, risk communication, and qualitative research methods. The draft interview guide was pilot tested with a research team member who resides in Appalachia. The interview guide was refined for clarity following the pilot test. The first author, who had established trusting relationships with WWTP operators through her weekly sample collection role for the broader wastewater surveillance study, conducted all interviews. An experienced infectious disease case investigator, she conducted interviews via Zoom, telephone, or in-person. Interviews lasted between 8-20 minutes (average 12.8 minutes). Every participant responded to 15 questions concerning perceived trustworthiness of COVID-19 information sources, perceived COVID-19 information gaps in their communities, and perceptions of communication channels used locally for obtaining COVID-19 information. The audio recording of each interview was transcribed verbatim using NVivo 12 (QRS International) software. Transcripts were coded independently by 3 research team members, including the researcher who conducted the interviews, using NVivo 12 coding software for open and axial coding.Reference Tracy 8

Our team mapped interview data to constructs from the CDC CERC framework, while also examining perceptions of specific COVID-19 information sources. We then performed iterative thematic analysis of data.Reference Tracy 8 Themes related to CERC principles were derived deductively from the data, while open coding allowed for the inductive inclusion of emergent themes.Reference Tracy 8 Team members met multiple times via teleconference to discuss and iteratively revise the codebook. This approach is consistent with Consensual Qualitative Research, which posits that a team of coders analyzing data first independently, then coming to a single unified analytic vision through dialogue can reduce individual bias while strengthening the team’s ability to capture the complexity of the data.Reference Hill, Thompson and Williams 9 To further enhance rigor, member checks were conducted with respondents, who reviewed and provided feedback on preliminary findings.

Results

Among the 8 people interviewed, 7 were white/non-Hispanic male residents and 1 was a white/non-Hispanic female resident of rural Appalachian eastern Kentucky. All respondents were employed by a municipal WWTP. The demographic homogeneity of wastewater plant operators reflected the demographics of the region and profession.

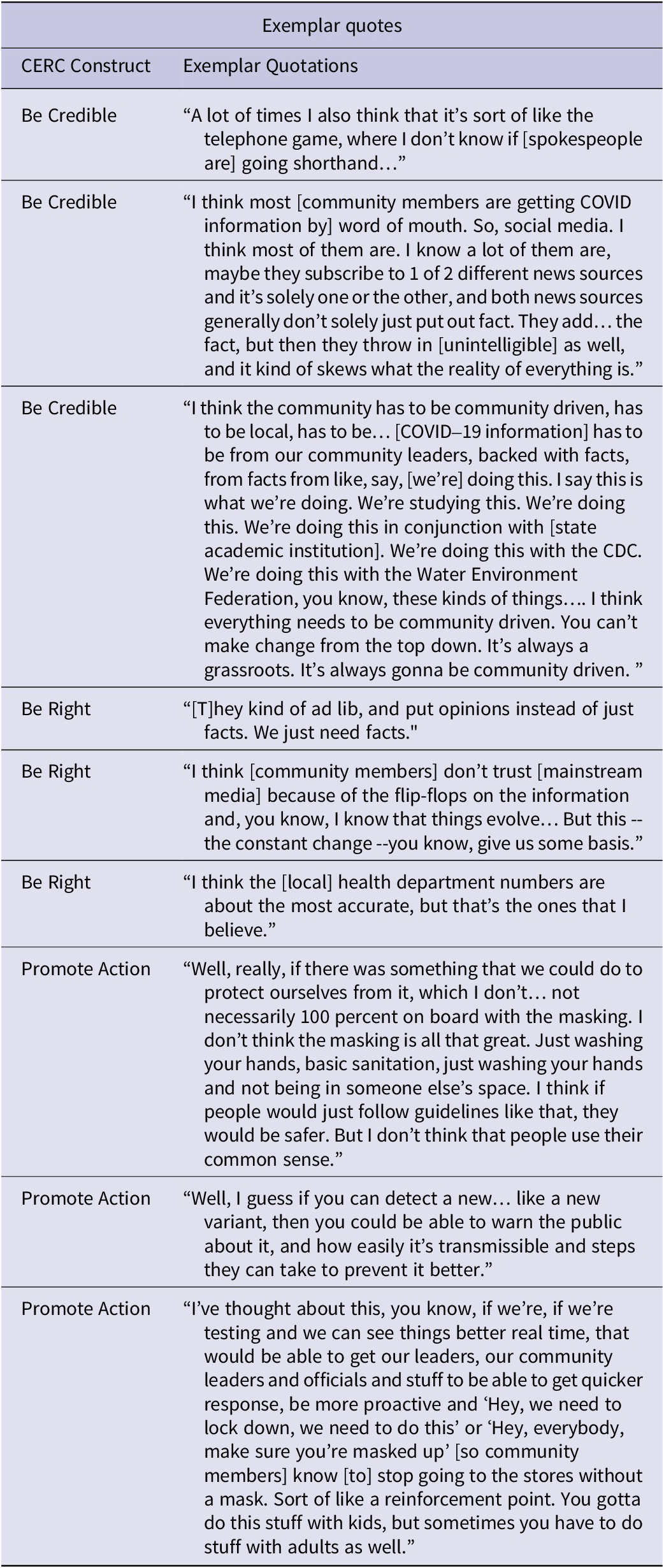

In reference to COVID-19 mitigation communication, we found that respondents most often made statements related to the “Be Credible,” “Be Right,” and “Promote Action” CERC constructs. References to these 3 constructs accounted for 88% (29/33) of the references mapped (Table 1). The “Show Respect” construct had no mapped thematic data. Quotes related to “Be Credible,” “Be Right,” and “Promote Action” are in Table 2.

Table 1. CERC construct code counts

Table 2. Exemplar quotes

Thematic analysis indicated that multiple factors - including large volume of information, large number of information sources, and misinformation – contributed both to uncertainty about where to find reliable COVID-19 information and to distrust in messages.

Respondents were asked to share their perceptions about how best to communicate health risks with their communities. Several responses reflected credibility challenges for both messages and messengers, indicating that tailored approaches may be more effective. One respondent noted, “I think everything needs to be community driven. You can’t make change from the top down.” Another respondent noted, “… national news is less trustworthy than your local news.” A third respondent acknowledged the struggle their community had finding what they would accept as credible information, explaining, “…the fact that we are still very somewhat [sic] rural area, and there’s a lot of misinformation that’s out there on the internet, television, that sort of thing… [P]eople around here just really don’t know what media sources to trust…” Another respondent pointed out that inconsistent messaging also made it difficult to know what information was credible, stating, “… ‘Wear a mask, don’t wear a mask, wear a mask, wear 2 masks, wear a mask indoors, don’t wear a mask outdoors, wear a mask outdoors,” and adding, “… there’s got to be some kind of consistency to the message, or it’s completely lost.”

Some respondents indicated that information from local hospitals and public health experts was not necessarily deemed credible. Specifically, 1 participant questioned mortality data: “I think [community members] probably trust the hospital because…they’re the ones that are treating the patients… But there’s also a lot of information out there…that you don’t know if it’s true or not that no matter what you die of… they’re going to turn it in as COVID to get that money.”

Additional themes emerged as potential mediators of trust. For example, political party affiliation of public health messengers influenced the perceived trustworthiness of their COVID-19 messages. Several respondents indicated a low level of perceived credibility in COVID-19 messengers due to their status as an elected official and/or partisan affiliation. When asked if they watched press conferences to obtain information about COVID-19, 1 respondent noted, “I did at first when… they had [Dr. Fauci] and President Trump on there, but since then, I don’t pay much attention to ’em.” Another respondent acknowledged, “When it comes to politics… [members of my community] won’t trust the other side.” Additional evidence of distrust of elected officials and government agencies was exemplified by a participant who responded “Oh, you don’t believe nobody in politics, especially the state governments… They lie about one thing, they lie about everything else.”

One respondent recognized the need for actionable mitigation measures like wastewater surveillance: “…if we’re testing and we can see things better real time, [we] would be able to get our leaders, our community leaders and officials and stuff to be able to get quicker response, be more proactive.”

Discussion

This study described perceptions of COVID-19 messages and messengers by wastewater treatment plant operators in eastern Kentucky and used the CERC model to understand potential communicative drivers of these perceptions. We found that most respondents expressed difficulty trusting public health information, which may contribute challenges for implementing rural wastewater surveillance initiatives in the future. A key factor contributing to mistrust among respondents was the perceived absence of credibility among messengers.

Within the CERC framework, credibility is characterized as an unwillingness to compromise on honesty and truthfulness. 6 Interestingly, credibility is the only CERC construct that cannot be controlled for when designing message content; it is mediated by receiver perceptions of the messenger. However, perception of the messenger as an expert may not confer credibility if the experts’ opinion is in contradiction with an individual’s worldview.Reference Lachapelle, Montpetit and Gauvin 10 If the perceived absence of credibility encourages mistrust, public health leaders must proactively develop new and shared understandings regarding the establishment and maintenance of messenger credibility. This task begs the question of what factors make health messages and messengers credible for rural audiences and further centers local contexts when designing and implementing wastewater surveillance and other pandemic mitigation strategies.

Our findings align with growing evidence that those who present themselves as experts in public health, medicine, and public policy cannot assume that they will be perceived as credible.Reference Lachapelle, Montpetit and Gauvin 10 Information, such as mortality data, that experts may assume is incontrovertible, may generate skepticism, as exemplified by a participant who asked, “…[C]an we really believe all the numbers?” Further research is needed to determine mechanisms that bolster the credibility of both health information and messengers in rural communities amidst challenging sociopolitical climates.

Limitations

The small sample size (N=8) and qualitative nature of this study limit the generalizability of our findings; however, the results provide transferrable insights for teams seeking to implement wastewater surveillance in similar settings and populations. While demographic homogeneity may have contributed to relative response uniformity, this homogeneity largely reflects the demographics of the region, predominantly white non-Hispanic, as well as demographics in the profession. 7

While respondents’ knowledge of the interviewer’s role as a COVID-19 wastewater surveillance researcher may have influenced responses, community-engaged qualitative research recognizes the benefits arising from the process of building relationships among researchers and participants.Reference Tracy 8

Conclusions

This study highlights that perceived credibility is critical for successfully communicating health risks to the public. Additional research is needed to elucidate which combinations of message, messenger, and dissemination strategies increase the perceived credibility of information for rural audiences, particularly in cases of emerging and quickly evolving scientific evidence. Emphasizing CERC constructs related to credibility, accuracy, and action when developing messaging strategies may benefit communication effectiveness for public health-focused teams seeking to implement pandemic wastewater surveillance strategies in the rural US.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIH RADx-rad Initiative Grant #U01 DE053903-01. Thank you to the Eastern Kentucky wastewater treatment plant staff who provided interviews and feedback for this study.

Author contribution

Savannah G. Tucker MPH: Drafting data collection instruments and procedures, data collection, drafting, analysis; Beverly May MSN DrPH: Drafting, analysis; Matthew Liversedge: Drafting data collection instruments and procedures, drafting, analysis; Scott Berry MBA PhD: Editing; James W Keck MD MPH: Drafting data collection instruments and procedures, drafting, editing; Anna Goodman Hoover MA PhD: Drafting data collection instruments and procedures Drafting, Editing, Analysis.