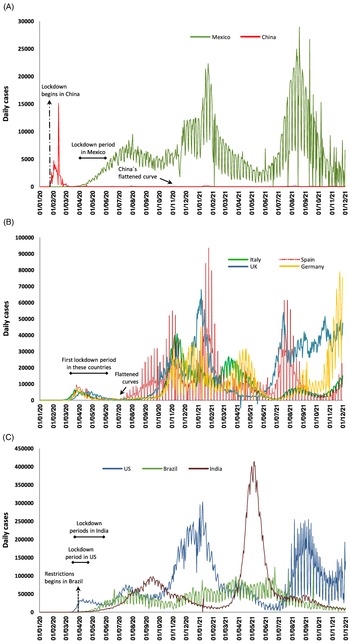

Nowadays, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been one of the greatest challenges for the entire world. One of the biggest questions asked during the first year of this pandemic was: How can we return to normal without causing new waves of infections? Despite the fact that the COVID-19 outbreak began in China, this country applied its experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) allowing a rapid response to this public-health emergency. Reference Nkengasong1 Thus, in January 2020, the country imposed strict measures such as home quarantine, traffic restrictions, travel bans, cancelation of public activities, postponement of festivals, the use of face masks in public, and the extension of winter break; thus, the return to work and school reopening were postponed. Reference Taghrir, Akbarialiabad and Marzaleh2,Reference Zhang, Jiang and Yuan3 After applying these measures, the epidemic curve decreased and remained flat until the end of 2021, with China being one of the countries with the fewest daily new cases and deaths from this disease in the world (Figure 1). 4

Figure 1. Lockdowns and daily new cases of COVID-19 in Mexico and other countries around the world. The data were obtained from Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center (from January 2020 to December 2021). 4 Lockdowns and flattened curves are indicated by horizontal lines and arrows. (A) China and Mexico; Reference Taghrir, Akbarialiabad and Marzaleh2,10,11 (B) Germany, Italy, Spain, and UK; Reference Glass5 and (C) United States, Brazil, and India. Reference Zhang and Warner6,Reference Ruiz-Roso, de Carvalho Padilha and Mantilla-Escalante8,Reference Soni9

In Europe, the response to this pandemic was not the same as in China. During March 2020, lockdowns were introduced in several European countries to stop the spread of SARS-coronavirus 2 (CoV-2), just when the disease had already caused thousands of cases and hundreds of deaths. A few weeks later, the epidemic curves flattened and countries relaxed their respective lockdowns. Nevertheless, the subsequent COVID-19 waves that occurred during the following months of 2020 and 2021 increased the number of daily new cases and deaths (Figure 1). 4,Reference Glass5

On the other hand, the COVID-19 pandemic was not handled properly in some American countries; for example, after two months of confinement, the United States decided to reopen its economic activities, despite the fact that the epidemic curve had not flattened. Reference Zhang and Warner6 A similar situation occurred in Brazil, where this country relaxed its restrictions without considering that the number of COVID-19 cases was increasing. Reference Neiva, Carvalho and Costa Filho7,Reference Ruiz-Roso, de Carvalho Padilha and Mantilla-Escalante8 Unfortunately, these countries lost control of their pandemics and became, along with India, Reference Soni9 the countries with the highest number of cases and deaths caused by this disease in the whole world (Figure 1). 4

The Mexican Government should have considered the experience of these countries to manage its pandemic. In this sense, Mexico’s response was rapid and the Government applied strict measures to contain the spread during March 2020. 10 However, similar to the handling of this pandemic in the United States and Brazil, Mexico decided to ease some restrictions to reopen economic activities, just when the number of cases and deaths of COVID-19 had increased rapidly during the month of May 2020 (Figure 1). 4,11 This hasty decision was counterproductive, because the number of daily new cases and deaths continued to rise during the following months of 2020, and the health system collapsed due to the new waves of COVID-19 caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 variants that appeared during 2021 (Figure 1). 4,12 Nevertheless, Mexico decided to continue with the reopening with its health consequences. Despite the sentinel surveillance system adopted by the Government, 13 during 2020, Mexico was among the top 10 countries with the highest number of COVID-19 cases; and during 2020 and 2021, the country was among the top 5 countries with the highest number of deaths caused by this disease. 4

If Mexico does not want to continue seeing its health system collapse due to the new COVID-19 waves or another pandemic, the country must learn its own lesson and follow the example of China, where the Government admitted very early, the existence of a novel coronavirus and responded quickly to address the outbreak. Reference Nkengasong1 To be prepared for another public health emergency of international concern, the Mexican Government must be willing to enforce strict measures, including border control and airport arrivals, and mandatory use of face masks.

Acknowledgments

We thank Francisco José Aréchiga-Ceballos for reviewing this manuscript.

Author contributions

Sergio Isaac De La Cruz-Hernández analyzed the epidemiological data and other data sources, wrote the manuscript and supported to make the figure. Ana Karen Álvarez-Contreras obtained the epidemiological data from Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, Coronavirus Resource Center and made the figure.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.