Public health emergencies often expose humanity to uncertainty, fear, and chaos.Reference Wen, Zhang and McGhee 1 Frustratingly, society is increasingly confronted with potential threats posed by emerging “diseases X.”Reference Cousins 2 It is difficult to anticipate the challenges and responses of the next public health crisis. FeldmanHall and ShenhavReference FeldmanHall and Shenhav 3 suggest that learning from past experiences is a key strategy to cope with uncertainty. Therefore, drawing lessons from the past is essential for navigating future uncertainties related to public health crises.

The early responses to COVID-19 from the people of Wuhan, China, serve as an important case study in this regard. Wuhan was the first city in the world to encounter and suffer from the attack of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.Reference Zhu, Wei and Niu 4 At the beginning of 2020, the virus was a mystery to the Wuhan people. They had limited knowledge about its pathogenesis, transmission, and associated health consequences after infection.Reference El Zowalaty and Järhult 5 -Reference Russell, Spence and Chase 8 This information uncertainty sparked widespread panic. Besides, Wuhan was also the pioneer in executing a large-scale lockdown, a move abrupt and unrivaled in its scale.Reference Qian and Hanser 9 This intervention disrupted people’s daily lives significantly.Reference Cheng, Xia and Pang 10 Consequently, unprepared individuals confronted panic due to supply deficitReference Guo, Hou and Xiang 11 and severe psychological stress.Reference Hanson, Belderson and Ward 12 Nonetheless, Wuhan people did not remain passive during the crisis. They undertook substantial self-help efforts via social media. This is manifested in a great number of messages containing social support exchanges on Weibo. These data could be invaluable in providing guidance and instructions to individuals in the evolving uncertainties.Reference Jong, Liang and Yang 13 , Reference Schuchat 14

Given this, the present study aims to reexamine the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, investigating people’s needs, their awareness of the disease, the strategies they used to gain attention, and the differential behaviors demonstrated by professionals and laypeople. We hope our findings will offer valuable insights that will guide society in managing future public health emergencies.

The Current Study

The unprecedented lockdown in Wuhan significantly impacted people’s ability to connect with others,Reference Saud, Mashud and Ida 15 creating a strong demand for online social support exchanges.Reference Seiter and Brophy 16 In response to the unfamiliar public health crisis, a vast online group spontaneously formed on Weibo, utilizing the specific topic tag “COVID-19 Mutual Aid” (#新冠肺炎互助). Given the novel and challenging situation in Wuhan and the strict lockdown policy, it is essential to understand the context of social support behaviors at the early stage of the pandemic, especially of those infected with COVID-19. Therefore, we propose the following research question:

RQ1: During the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, what are the (a) number and (b) proportion of social support messages in the COVID-19 Mutual Aid Weibo Group? Which (c) orientation and (d) type of social support messages is more/the most prevalent?

Additionally, social support exchange behavior often involves self-disclosure, which is seen as an important strategy for obtaining social support.Reference Derlega, Metts and Petronio 17 Self-disclosure can help individuals build trust in interpersonal communication.Reference Mesch and Beker 18 However, the richness of self-disclosure can affect the completeness of information that the audience receives. In online mutual helping, information completeness is an essential component of content credibility.Reference Luo, Li and Chen 19 It refers to the richness and clarity of information provided by an individual.Reference Stvilia, Mon and Yi 20 Because completeness and credibility are strongly related, completeness affects people’s perception of the quality of online information.Reference Bates, Romina and Ahmed 21 As people increasingly rely on online information for decision-making,Reference Barry and Schamber 22 information completeness naturally becomes one of the most critical criteria in choice-making and action-taking.Reference Cline and Haynes 23 , Reference Eysenbach, Powell and Kuss 24

During the Wuhan lockdown, both the depth of self-disclosure and the richness of social support types in help-seeking posts were used as strategies to attract social concerns and were displayed on social media platforms as retransmissions (specifically, the number of reposts).Reference Luo, Li and Chen 19 , Reference Pan, Feng and Skye Wingate 25 , Reference Wingate, Feng and Kim 26 Retransmission was vital during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, not only because it was considered a measure of communication effectiveness.Reference Liu, Lu and Wang 27 -Reference Yang, Tufts and Ungar 29 More significantly, wide reposting equaled more opportunities for help-seekers to receive support, which would help authorities better understand the people’s needs and address potential resource shortages and other urgent issues.

Regarding Wuhan people’s online self-disclosures during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, we found that they tried to use their words to describe the clinical manifestations of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, dyspnea, fatigue, diarrhea, and vomiting)Reference Zhu, Ji and Pang 30 and to evaluate their disease statuses online. The more complete symptoms people disclose (the more severe the illness), the more social concerns or support they might receive.Reference Luo, Li and Chen 19 , Reference Huang 31 Thus, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: The completeness of self-disclosure about symptoms (disease statuses) in the COVID-19 Mutual Aid posts is positively associated with retransmission.

In addition to self-disclosure about symptoms, the description of chest CT results in the COVID-19 Help-Seeking posts also caught our attention because chest CT results were used to diagnose COVID-19 in the early pandemic in Wuhan.Reference Kanne, Bai and Bernheim 32 , Reference Kwee and Kwee 33 Thus, we raise another hypothesis:

H2: The self-disclosure of chest CT results in the COVID-19 Mutual Aid posts is positively associated with retransmission.

Furthermore, we observed that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Wuhan people did not limit themselves to seeking a singular form of social support. Instead, they actively sought multiple forms of support at the same time. This trend was also observed in the provision of social support. In other words, a single message could contain various types of social support.Reference Barrera 34 According to the social support theory, the completeness of the types of social support sought or offered is directly linked to an individual’s personal situation.Reference Glanz, Rimer and Viswanath 35 The more diverse the social support an individual seeks, the more difficult their situation likely is. Similarly, the completeness of the types of social support offered reflects one’s good situation and ability to help others. Based on these findings, we speculate that the completeness of the types of social support sought or offered will result in more reposts. Therefore, we posit the following hypotheses:

H3: The completeness of the types of seeking social support in the COVID-19 Mutual Aid posts is positively associated with retransmission.

H4: The completeness of the types of offering social support in the COVID-19 Mutual Aid posts is positively associated with retransmission.

In terms of the recognition and handling of COVID-19, there may be a difference between health professionals and the general public.Reference Luo, Ji, Tang and Du 36 Previous studies have shown that health professionals have expertise in understanding and managing illnesses,Reference Albarrak, Mohammed and Al Elayan 37 -Reference Hafiz, D’Sa and Zamzam 39 while the gap between health professionals and laypeople indicates a lack of knowledge.Reference Larrouy-Maestri, Magis and Grabenhorst 40 This gap in knowledge may lead to subjective and emotional perceptions and behaviors among laypeople, while professionals are seen as objective and reliable.Reference El Zowalaty and Järhult 5 , Reference Larrouy-Maestri, Magis and Grabenhorst 40 , Reference Covello, Flamm and Rodricks 41 However, in the early stages of the pandemic, the knowledge gap may have been small between health professionals and the laypeople, as COVID-19 was a new and unfamiliar disease for everyone in Wuhan at that time. Moreover, it is unclear whether this divergence in knowledge is reflected in different types of self-disclosure. Therefore, the following research questions are proposed:

RQ2: Is there any significant difference between laypeople and health professionals in disclosing the completeness of symptoms (disease statuses)?

RQ3: Is there any significant difference between laypeople and health professionals in disclosing chest CT results?

Methods

Data Collection

With the help of web crawlers, this study employed quantitative content analysis to examine posts tagged with “COVID-19 Mutual Aid”(#新冠肺炎互助) on Weibo, one of China’s most popular social media platforms, during the initial phase of the pandemic. The analysis period spanned from January 23, 2020, the date of Wuhan’s lockdown, to March 23, 2020. Our selection criteria included posts from individuals who self-reported as being (or likely being) infected with COVID-19, and we further refined our dataset by excluding geotags outside of Wuhan. The data was retrieved on January 11, 2022. Ultimately, we gathered 2207 valid samples for coding and subsequent analysis.

Coding Procedures and Operationalization of Variables

Social support

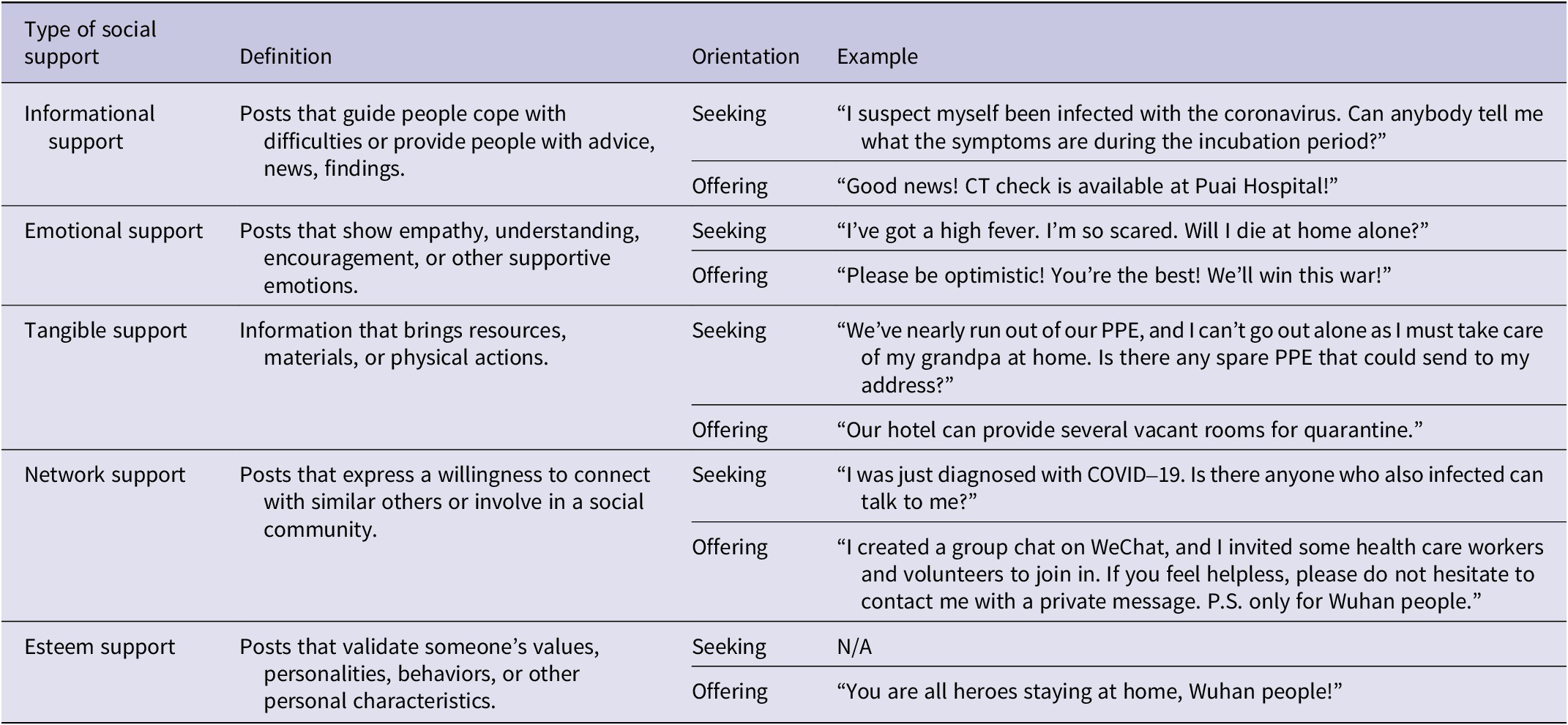

In accordance with the classification suggested by Cutrona and Suhr,Reference Cutrona and Suhr 42 Table 1 presents definitions and examples of social support exchange types (esteem support seeking was not identified in our coding procedures). All items were coded as 1 if mentioned and 0 if not mentioned in the selected posts.

Table 1. Definitions and examples of different social support messages

Note: Seeking esteem support was not found in our coding procedures.

The completeness of seeking/offering social support types

Considering that residents of Wuhan rarely sought or provided a single type of social support, we introduced two new variables: the completeness of sought social support types and the completeness of offered social support types. These variables, ranging from 0 to 5, were employed to evaluate their personal circumstances. Each time a type of social support (informational, emotional, tangible, network, or esteem) was referenced in a post, a point was added to the corresponding completeness score.

The completeness of self-disclosure about symptoms

Given the limited understanding of COVID-19 among individuals during the Wuhan lockdown, there were no specific standards for describing the clinical manifestations of the disease at the onset of the pandemic. This was evident in our pilot coding process, where individuals described their symptoms in various ways.

Subsequently, we referred to the clinical characteristics of COVID-19, as later described by Zhu et al.,Reference Zhu, Ji and Pang 30 and our observations from the pilot coding. From this, we identified the 5 most common symptoms: fever, dyspnea, fatigue, cough, and diarrhea/vomiting. It is important to note that diarrhea and vomiting were frequently grouped together in the descriptions within our sampled posts, leading us to categorize them as a single item.

We coded the presence of symptoms as 1 and the absence as 0. We then added the score(s) to create a “completeness” variable for self-disclosure about symptoms, with values ranging from 0 to 5, to assess individuals’ health statuses.

Chest CT results

According to Zhong et al.,Reference Zhong, Zhang and Wang 43 there are 6 manifestations of COVID-19 infection identifiable in chest CT scans: ground-glass opacity, consolidation, fibrous strip shadow, interlobular and/or intralobular septal thickening, subpleural curvilinear line, and traction bronchiectasis. However, since most people are not medical professionals, they may lack a clear understanding of these 6 manifestations as reflected in CT results.

This was reflected in our coding process, where we found that over 80% of the sampled posts from individuals who underwent chest CT scans did not describe these manifestations. Instead, they simply attached CT images or stated the CT results indicated they were (likely) infected. Consequently, the depth or completeness of self-disclosure about chest CT results is not applicable in this research.

As previously clarified, this study only selected posts from individuals who claimed they were (likely) infected. Therefore, posts that disclosed chest CT results or attached CT images may be more credible than those that did not. We coded posts that mentioned chest CT results or included CT images as 1, whereas all other posts were coded as 0.

Identities

Posts from individuals with verified identities or those who claimed to be health professionals (e.g., medics, hospital workers, or medical school students) were coded as 1, whereas those from others were coded as 2 (considered laypeople).

Intercoder Reliability

For the coding process, two native Chinese graduate students majoring in media and communication were invited. Before coding, detailed explanations, definitions, and examples of each item were provided to the coders. After sufficient training, we assessed the intercoder reliability of the two coders by randomly selecting and double-coding 330 posts (14.95%) from the total sample. The Cohen’s kappa coefficients for each coding item ranged from 0.82 to 0.93, indicating good agreement between the two raters.

Results

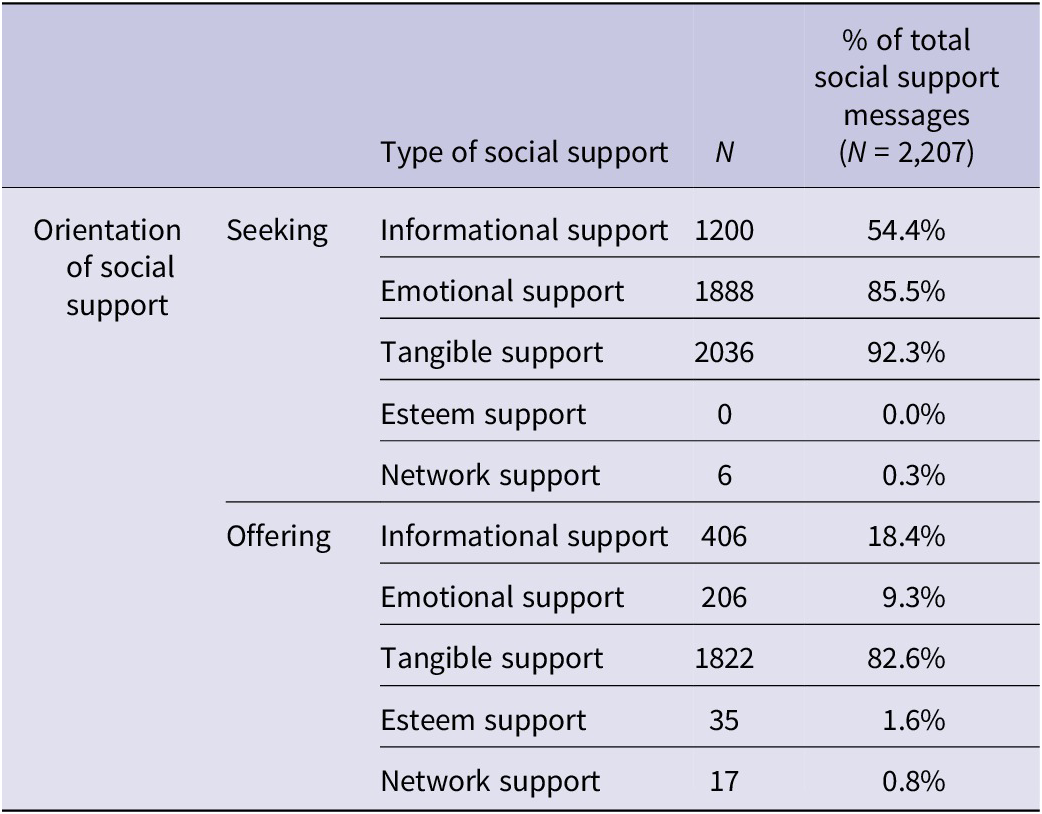

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 2 provide an answer RQ1. Out of the 2207 chosen posts from the “COVID-19 Mutual Aid” group, seeking tangible support was the most frequent social support message (N = 2036, 92.3%), followed by seeking emotional support (N = 1888, 85.5%), offering tangible support (N = 1822, 82.6%), and seeking informational support (N = 1200, 54.4%). The less common social support messages were offering informational support (N = 406, 18.4%), offering emotional support (N = 206, 9.3%), offering esteem support (N = 35, 1.6%), offering network support (N = 17, 0.8%), and seeking network support (N = 6, 0.3%). It was observed that posts seeking esteem support were not found in the “COVID-19 Mutual Aid” group. Compared to the orientation of offering, messages seeking social support were more prevalent.

Table 2. Frequencies of social support exchange

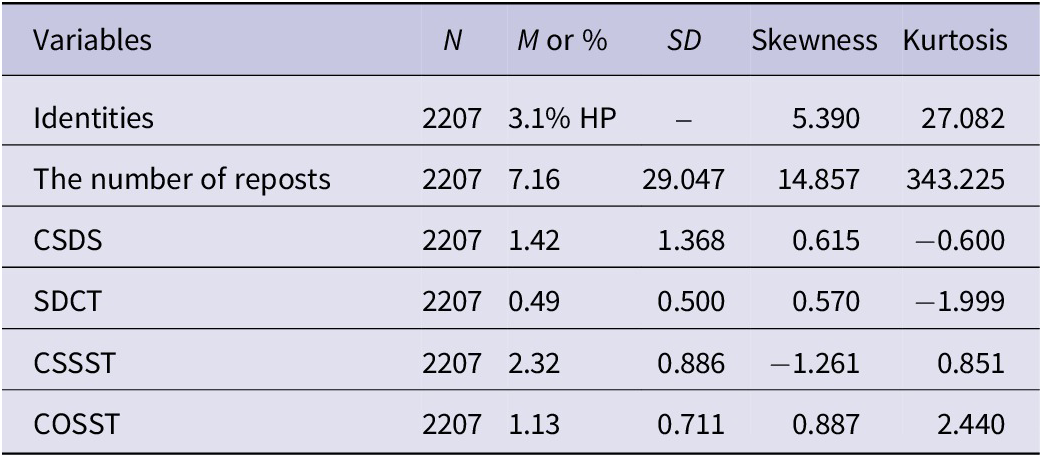

Prior to conducting further analyses, we checked the normality of all variables (see Table 3). We found that identities and the number of reposts exceeded the absolute value based on the criterion of skewness (< 2) and kurtosis (< 7).Reference Curran, West and Finch 44 This meant that traditional linear regression analysis was not appropriate for testing H1, H2, H3, and H4 because the dependent variable (the number of reposts) was non-normal, non-continuous, and overdispersed.Reference Oztig and Askin 45 Moreover, the variance of the number of reposts was larger than its mean, which violated the assumption of equidispersion for Poisson regression analysis.Reference Seiter and Brophy 16 , Reference Denham and Denham 46 DenhamReference Denham and Denham 46 suggested that count data (such as retweet frequency) usually follow binomial distributions, and negative binomial regression analysis could be a suitable modeling technique.

Table 3. Summary of statistics of all variables

Note: HP = health professionals; CSDS = the completeness of self-disclosure about symptoms; SDCT = self-disclosure of chest CT results; CSSST = the completeness of seeking social support types; COSST = the completeness offering social support types.

However, since there were many zero counts in the number of reposts (N = 1112, 50.4%), a standard negative binomial regression model was not ideal either. Based on the methods from similar studiesReference Xie and Liu 47 , Reference Muniz-Rodriguez, Schwind and Yin 48 and the recommendations from Feng,Reference Feng 49 we considered using either zero-inflated negative binomial regression (ZINB model) or hurdle regression model, as they could account for the excess zeros in our dependent variable. To determine which model was more fitting for our data, we used the Vuong test.Reference Feng 49 , Reference Cameron and Trivedi 50 We finally chose the hurdle model, as the results indicated that it had better fit, because the Vuong z-statistic value (2.798) was positive and significant (p < 0.05).

The results of the hurdle regression model are summarized in Table 4. The findings show that posts disclosing symptoms were more likely to be reposted than those without symptoms (aOR = 1.093, p < 0.05). Moreover, the number of reposts increased significantly with the number of symptoms disclosed. Specifically, disclosing one more symptom would increase the probability of being reposted by 20.6% (aRR = 1.206, p < 0.01). Therefore, H1 was supported.

Table 4. Hurdle regression model (dependent variable: the number of reposts)

Note: CSDS = the completeness of self-disclosure about symptoms; SDCT = self-disclosure of chest CT results; CSSST = the completeness of seeking social support types; COSST = the completeness offering social support types.

Regarding the self-disclosure of chest CT results, posts that mentioned chest CT results or attached CT images were also more likely to be reposted than those that did not report CT results (aOR = 1.265, p < 0.05). H2 was supported.

When it comes to personal situations, posts that sought social support were more likely to be reposted (aOR=1.536, p < 0.001). However, a higher completeness of seeking social support types did not significantly influence the retransmission of the posts (aRR = 1.056, p = 0.534). However, posts that offered social support did not significantly affect the likelihood of being reposted (aOR = 1.062, p = 0.353), nor did a higher completeness of offering social support types (aRR = 1.101, p = 0.415). Thus, H3 and H4 were not supported.

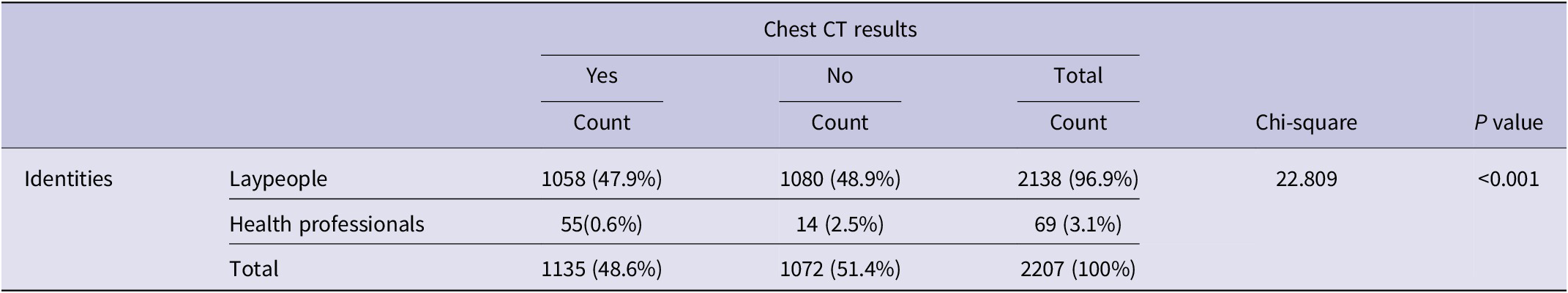

For RQ2, a Chi-Square test (see Table 5) was performed, and a significant difference was observed between health professionals and laypeople in disclosing chest CT results (χ 2 = 22.809, p < 0.001). Specifically, 49.5% of laypeople (N = 1058, N total = 2138) chose to disclose chest CT results, whereas 79.7% of health professionals (N = 55, N total = 69) did the same.

Table 5. Chi-square test

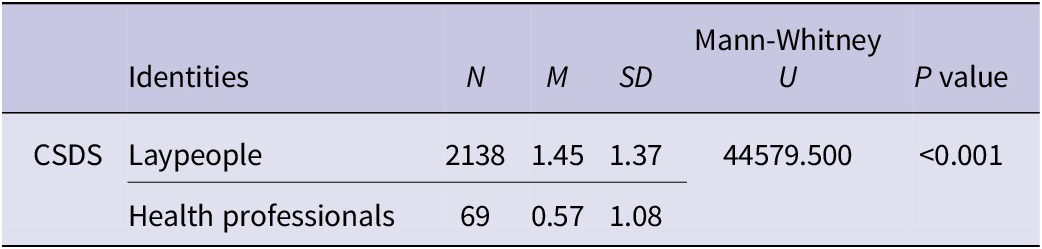

Since the Identities variable was not normally distributed, an independent samples Mann-Whitney U test (see Table 6) was used to investigate RQ3. The results showed that laypeople were more likely to self-disclose their symptoms on Weibo (M = 1.45) than the health professionals (M = 0.57) (p < 0.001).

Table 6. Independent samples Mann-Whitney U test

Note: CSDS = the completeness of self-disclosure about symptoms.

Discussion

This study looked back to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, focusing on how online social support exchange was presented, how self-disclosure strategies affected retransmission, and how health professionals and laypeople differed in online mutual support. First, our findings revealed that tangible support, emotional support, and informational support were the most common types sought, which is consistent with previous research that the public had a high demand for health resources, equipment,Reference Yin, Lv and Zhang 51 information, and emotional supportReference Liu, Zhu and Xia 52 during the early stage of the outbreak. The restriction policy and panic buying during a pandemic usually worsen resource shortages,Reference Pickles 53 explaining the prevalence of seeking tangible support on social media. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic was perceived as uncertain at the start,Reference Sidi 54 leading to a high demand for informational support on Weibo. Moreover, psychological stress was the most common problem faced by the public during the pandemic, motivating the seeking of emotional support as it can buffer mental stresses.Reference Szkody, Stearns and Stanhope 55

Moreover, the finding that messages offering social support were less prevalent also demonstrates that Wuhan people were in a tough situation during lockdown, as the amount of help-giving did not match that of help-seeking. However, we can see that tangible needs were well addressed on Weibo, which recognizes the role of social media in organizing mutual-aid movements to some degree. Thus, for future public crises, the administration should place a high value on social media’s role in source mobilization,Reference Pickles 53 psychological interventions,Reference Saltzman, Hansel and Bordnick 56 , Reference Shah, Kamrai and Mekala 57 , Reference Yu, Li and Li 58 correcting misinformation,Reference Bode and Vraga 59 , Reference van der Meer and Jin 60 , Reference Walter, Brooks and Saucier 61 and spreading accurate information.Reference Liu, Zhu and Xia 52

Regarding the relationship between the completeness of self-disclosure and retransmission, we observed that users who disclosed more symptoms received more reposts. This can be attributed to the fact that a diverse range of symptom descriptions not only implies higher content credibility, but also reflects disease severity.Reference Luo, Li and Chen 19 Especially, disease severity can elicit public empathy, resulting in positive responses from others.Reference Qin, Yang and Jiang 62 Therefore, a deep self-disclosure strategy is more likely to generate more social concern during a public health crisis. This finding supports Umar et al.’s63 observation that social media users intentionally self-disclose during the COVID-19 pandemic to gain social attention, rewards, and interactions. However, it should be noted that the practice of disclosing symptoms requires improved health literacy to ensure individuals do not exaggerate their illness. Additionally, the study found that the disclosure of CT results was positively associated with repost frequency, indicating that providing evidence increases information credibility and attracts more attention. Therefore, it is recommended to provide evidence in future online help-seeking activities. Overall, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the general motivations and ways of disclosing information online,Reference Nabity-Grover, Cheung and Thatcher 64 as traditionally online self-disclosure is driven by convenience for relationship maintenance, relation-building,Reference Liu, Min and Zhai 65 enjoyment, and self-presentation.Reference Kramer, Haferkamp, Trepte and Reinecke 66 Our findings highlighted the importance of self-disclosure and evidence-based information in online help-seeking during public health crises.

We also examined the relationship between the completeness of seeking/offering social support types and retransmission in crisis situations. We found that posts that sought social support, regardless of the number and type of support, were more likely to be reposted. This indicates that the public does not differentiate between the various needs of the seekers in times of crisis. They are willing to share any message that expresses a need for help or support. However, we found that posts that offered social support, whether one or multiple types, did not attract more reposts. A possible reason for this is that offering social support types implies that the poster is in a good situation and has the capacity to help others. Compared to the orientation of giving, reposters are more likely to transmit messages that show an urgent situation. This also highlights the importance of empathy in eliciting social concerns.Reference Umar, Akiti, Squicciarini, Dong, Kourtellis, Hammer and Lozano 63

In regard to the comparison between health professionals and laypeople, the study found a significant difference in disclosing CT results. A higher percentage of health professionals (79.7%) disclosed their chest CT results or attached chest CT results compared to laypeople (49.5%). This may be due to the health literacy gapReference Do, Tran and Phan 67 between the two groups or the easier access to medical resources for health professionals during the lockdown period. Besides, a statistical difference also exists in the disease status between health professionals and laypeople. Health professionals have lower mean scores and standard deviations in the completeness of self-disclosure of symptoms. This may be attributed to the health knowledge gap and health literacy gap.Reference Voigt-Barbarowicz, Dietz and Renken 68 Health professionals may describe their symptoms more accurately (not exaggerate), or their disease statuses were not severe (they protected themselves better). Although COVID-19 was unfamiliar to everyone in Wuhan at that time, we can see that health professionals still performed at a higher level of coping strategies.Reference Larrouy-Maestri, Magis and Grabenhorst 40 Overall, considering the discussion on the depth of self-disclosure and retransmission, the differences between laypeople and health professionals reveal that possessing a professional background would help cope with public crises.Reference Voigt-Barbarowicz, Dietz and Renken 68

Conclusion

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, discussions and concerns about this public health crisis have never ceased. The pandemic and its secondary impacts generated many uncertainties for people to understand and handle the unacquainted disease at the early stage of the outbreak.Reference Ciotti, Angeletti and Minieri 69 Now, with the accumulation of experience from all over the world, we can better recognize the virus and our situations. However, looking back at the beginning of the pandemic, the Wuhan people, who were the first vulnerable group to face uncertainty, struggled in the dark. In memory of the heroic deeds of the Wuhan people and to provide guidance for future crises, this study explored how Wuhan people coped with the unprecedented public health crisis on Weibo. Through a quantitative content analysis, 2207 valid Weibo posts tagged with “COVID-19 Mutual Aid” were analyzed. Descriptive statistics reveal that messages seeking tangible support, emotional support, and informational support were prevalent at the start of the pandemic. Our hurdle regression model illustrates that disclosing CT results and a deeper level of disclosure in disease statuses and bad personal situations would result in more retransmission. Additionally, the Chi-Square test and Mann-Whitney U test reveal that health professionals and laypeople have different self-disclosure strategies. Overall, our research on how Wuhan social media users were coping with the early phase of the pandemic through seeking and offering support online can inform authorities and individuals in their future responses to public health emergencies. Our findings also emphasize the importance of health knowledge and literacy.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the original data collected from Weibo posts contain rich information that could be further explored from various dimensions, but this study only focused on a few perspectives due to time and resource constraints. Second, the sample size of health professionals was relatively small compared to the number of ordinary people, which may affect the representativeness of the results. However, given that health professionals account for less than 1% of the total population in Hubei Province, 70 the sample size was considered reasonable. Third, as the data were retrieved on January 11, 2022, about 2 years after the sampling period, some posts may have been hidden, deleted, or censored by the users or the platform, which could lead to data loss. Finally, the generalizability of Wuhan’s experience of an unprecedented crisis to other contexts is uncertain. Future research should examine how people from different countries cope with the first lockdowns or the first wave of pandemic outbreaks with the help of social media platforms.

Author contribution

Yu Guo: conceptualization, data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition; Hongzhe Xiang: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, project administration; Yongkang Hou: conceptualization, writing - review & editing

Funding information

This study is supported by Higher Education Fund of Macau SAR Government (HSS-MUST-2021-02).

Competing interest

No conflict of interest declared.

Ethical standard

We declare that this study has been ethically reviewed and approved by board members of the Faculty of Humanities and Arts at Macau University of Science and Technology and is exempt from further ethical review as it uses only unobtrusive data/public data (social media data) and does not involve any interactions or interventions with human or animal subjects.