Introduction

Identifying the public’s subgroups regarding vaccination is a controversial endeavor. Reference Dubé, Laberge and Guay1 There were 3 main groups among the public with respect to vaccination: pro-vaccination individuals who accept all vaccines; those who are hesitant and have many concerns, but may entirely or partially vaccinate; and those who refuse all vaccines. However, the scientific literature in recent years has revealed a wide spectrum of subgroups regarding the issue of vaccination. Reference Larson, Jarrett, Eckersberger, Smith and Paterson2 For example, some studies have identified the public solely according to their attitudes about vaccination. Reference Gust, Brown and Sheedy3,Reference Keane, Walter and Patel4

However, other studies focused not only on vaccination attitudes, but also on vaccination behavior. These studies suggest that it is not accurate enough to identify the public solely according to their vaccination-related behaviors or attitudes, but rather based on a combination of both. For example, Benin et al. categorized their study participants based on a combination of behavior and attitudes. Reference Benin, Wisler-Scher, Colson, Shapiro and Holmboe5 Consistent with these findings, a previous study showed that pro-vaccination parents may have hesitant attitudes. These parents reported that they vaccinate their children with all the vaccinations but still have fears and concerns regarding the vaccines’ safety and effectiveness. Therefore, it is recommended that health authorities address the public’s fears and concerns in order to gain their trust, thus including those individuals who are pro-vaccination, and taking into consideration the difference between hesitant attitudes and hesitancy in practice among pro-vaccination parents. Reference Hijazi, Gesser-Edelsburg, Feder-Bubis and Mesch6

Vaccination information is delivered via various sources such as health organizations, healthcare workers, and social media. The reliability and accuracy of vaccination information are essential in making informed decisions. Reference Charron, Gautier and Jestin7–Reference Lai, Bodson and Davis10 Over the years, health organizations have dealt with ambiguous information delivered via media and interpersonal sources. Reference Signorini, Segre and Polgreen11,Reference Romo12 Traditionally, the myth-busting correction approach was used extensively by identifying the myth and providing a rebuttal. Reference Challenger, Sumner and Bott13 It was also done by distinguishing between myths and facts. Reference Baxendale and O’Toole14–Reference Miller16 However, this information correction method was found ineffective because repeating the myth only serves to make the information more familiar and therefore, more likely to be true. Reference Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz and Cook17 In addition, studies found that the public refused to accept a judgmental approach without scientific evidence to back it up. Reference Nyhan and Reifler18–Reference Gesser-Edelsburg20 As a result, this strategy of communicating information was found to be ineffective in several empiric studies and noted to have led to backfired effects. Reference Lewandowsky, Ecker, Seifert, Schwarz and Cook17,Reference Skurnik, Yoon, Park and Schwarz21,Reference Cook and Lewandowsky22

Health organizations still utilized the same communication strategy of distinguishing between myths and facts during the Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) crisis. During this period, health organizations continued along the same lines, treating any information that did not originate from them as ‘biased.’ Some of these organizations even cooperated with media giants such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon who removed and blocked information that was not in line with the information provided by the authorities. Reference Gesser-Edelsburg20

In light of the fact that vaccine hesitancy is becoming a central issue, health organizations worldwide need to address it. Despite several empirical studies that have emphasized the problematic and ineffective way in which health organizations ‘correct’ information which does not come from them, they have not yet found ways to properly address vaccine hesitancy. This empirical study seeks to deal with these 2 issues. It is worth noting that this study was conducted before the COVID-19 outbreak and seeks to (1) examine the responses of groups with different attitudes/ behaviors regarding vaccination, and (2) examine the effect of the common method of correcting information (which comes from unofficial sources) on the response of sub-populations; while examining issues of reliability, satisfaction, information seeking, and the ways in which health organization tools aid the decision-making process regarding vaccine.

Methods

Research design and procedure

This study is part of a larger study that used a controlled experiment in which participants were randomly divided into 2 groups. The experiment was conducted during the measles outbreak in Israel in January 2020. At that time, the authorities tried to impose sanctions to prevent unvaccinated children from entering kindergarten. The study aimed to examine how the Ministry of Health’s communication methods affected parents from different subgroups regarding vaccination. Both experimental conditions presented a simulation, starting with a dilemma regarding sending a child to kindergarten during the measles outbreak, knowing that some of the children in the kindergarten were un-vaccinated. The dilemma was followed by a mother’s post on Facebook containing information about measles and the measles vaccine. In the next stage, a health organization’s response was presented via 2 conditions: Condition 1 – common information communication approach formulated as a short response without addressing the emotional element (empathy and addressing the public’s fears and concerns) and in terms that dismiss critics and oppositional voices Reference Gesser-Edelsburg20 ; and Condition 2 – recommended (theory-based) information correction, mainly communicating information transparently and addressing the public’s concerns.

This study focuses only on Condition 1 (the common information communication approach) and is mainly based on a simulation that examines how groups with different attitudes and behaviors regarding vaccination respond to health organizations’ traditional way of communicating information during an epidemic outbreak.

The study was approved by the Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences Ethics Committee for Research with Human Subjects at the University of Haifa (approval no. 421/17).

Sampling and data collection

The participants were sampled from iPanel, an Israeli Internet panel. An online survey was distributed to a representative panel of the adult population in Israel. The online survey was designed using Qualtrics XM online (Qualtrics Survey Software, Qualtrics Inc., Provo, Utah, USA). The study included parents whose children were in kindergarten (aged 3 - 5 years). The rationale behind including only parents whose children are in kindergarten stems from the relevance of vaccines to this specific population and the similarity between the simulation in the study - of sending a child to kindergarten - and the participants’ real situation. The study included 150 parents who met the inclusion criteria. The participants were classified according to their vaccination behavior and attitude regarding vaccination.

Questionnaire structure

The first part of the questionnaire included a filtering question that asked if the participant was a parent of a child in kindergarten (aged 3 - 5 years). If the participants met the inclusion criteria, they were asked to fill out their demographic information and were then asked if they give their children all the vaccines according to the nationally stipulated vaccination schedule. Next, the questionnaire included a validated vaccine hesitancy scale to identify their attitudes. Reference Larson, Jarrett and Schulz23 The second part of the questionnaire was divided into 3 stages with each stage being followed by questions (see Table 1). The first stage presented a dilemma for parents about whether or not to send their children to kindergarten during a measles outbreak, knowing that some kindergarten children were not vaccinated because of their parents’ objection. In the next stage, they were shown a post written by the mother of one of the kindergarten children, containing information about measles and about the measles vaccine. In the third stage, the participants were shown a response by the official health authority (such as the Ministry of Health), trying to correct the information in the mother’s post. The correction was formulated based on previous statements of the Ministry of Health, which disregarded the public’s fears and concerns in relation to the mother who had written the post and the other parents.

Table 1. The questionnaire structure

Classification of the participants according to their actual vaccination behavior

To determine the participants’ actual vaccination behavior, they were asked if they give their children all of the vaccines according to the routine vaccination schedule. If they answered ‘yes,’ the participant was considered a pro-vaccination parent. If they answered ‘no,’ the participant was considered an anti-vaccination parent. However, in order to consider the participants vaccine-hesitant, they needed to answer: ‘I’m selective in vaccinating my children’ or ‘I give my children all of the vaccines, but not according to the routine vaccination schedule.’ A total of 115 pro-vaccination participants, 35 vaccine-hesitant participants, and 3 anti-vaccination participants answered the question. The anti-vaccination participants were excluded from the study because they were statistically a small group.

Classification of the participants according to their vaccination attitude

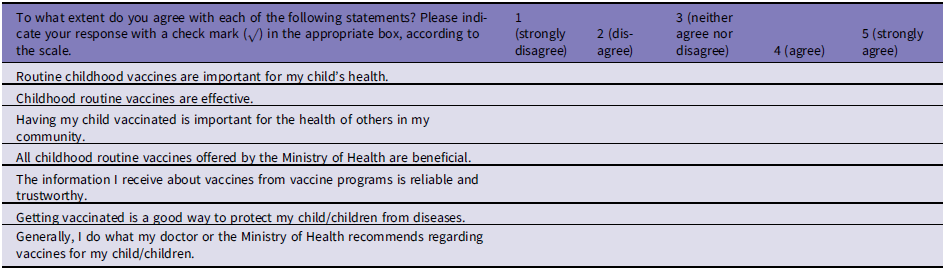

A vaccine hesitancy scale was designed to identify attitudes regarding vaccine effectiveness and importance. The scale was based on a previously validated vaccine hesitancy scale, Reference Larson, Jarrett and Schulz23 and included an index of 7 statements using a 5- point Likert scale in which participants were asked the extent to which they agree or disagree with each statement (Cronbach α = 0.91). The statements focused on the effectiveness and importance of routine vaccines (Table 2). The level of hesitation is indicated by the score of the 5- point Likert scale. An index score of 2 and below indicates low hesitation regarding vaccination. However, a high hesitation score should be above 2. The study included 114 participants with pro-vaccination attitudes (a score of 2 and below) and 36 participants with hesitant attitudes (a score above 2).

Table 2. Vaccine hesitancy 5-point Likert scale questions

Classification of the participants according to their vaccination attitude/ vaccination behavior

In order to examine how groups with different vaccination attitudes and behavior respond to the information corrections provided by the Ministry of Health, the participants were classified, using a combination of their vaccination attitude and vaccination behavior, into 4 groups: 102 pro-attitude/ pro-behavior (PA/PB) participants, 12 pro-attitude/ hesitant-behavior (PA/HB) participants, 13 hesitant-attitude/ pro-behavior participants (HA/PB), and 23 hesitant-attitude/ hesitant-behavior (HA/HB) participants.

Analysis

In the first stage, distributions were tested for the demographic questions. In the second stage, the measured variables were divided into 2 categories: category 1 measured variables before the participants’ exposure to the simulation, which included their trust in the Ministry of Health, information seeking, and health literacy; category 2 also measured variables after the participants’ exposure to the simulation. It included the reliability of the Ministry of Health’s response, the level of satisfaction with the Ministry of Health’s response, and the level of the help obtained from the Ministry of Health’s tools in making a decision about vaccine. The Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to evaluate the differences between the distribution of the measured variables among the four vaccination attitude/ behavior subgroups: PA/PB participants, PA/HB participants, HA/PB participants, and HA/HB. It was followed by the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Flinger method (DSCF) for multiple comparisons. In addition, the Chi-square test was used to test the variable of further information seeking following the Ministry of Health’s response in relation to the four different attitude/ behavior groups.

Reliability and validity

The current study and the research tools are based on two previous studies that we carried out. One study examined different groups in Israeli society using the hesitation scale. Reference Hijazi, Gesser-Edelsburg, Feder-Bubis and Mesch6 Another study which we conducted with students examined through simulation, the participants’ reactions to the Ministry of Health’s information transfer methods. Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Diamant, Hijazi and Mesch24

Results

The study participants included 31 (20.7%) males and 119 (79.3%) females. Most of the study participants (57.3%) were between 30 - 39 years of age, 22.7% were between 18 - 29 years of age, and 19.3% were between 40 - 49 years of age. The majority (73.3%) of the study participants were Jewish, and 21.3% were Arab. The majority (93.3%) of the study participants are married and have a BA (44.7%) or MA (19.3%) degree. As per religious affiliation, 76 (50.7%) are secular, 30 (20.0%) are traditional, 25 (16.7%) are religious, and 19 (12.7%) are ultra-Orthodox Jews (Table 3).

Table 3. Sociodemographic characteristics of the quantitative survey participants (n = 150)

Findings of the analysis of the measured variables before the participants’ exposure to the simulation

Two main variables were tested before the participants’ exposure to the simulation: (1) trust in the Ministry of Health and (2) information seeking and health literacy. According to the Kruskal-Wallis test results (Table 4), a significant difference was found in the level of trust in the Ministry of Health according to the vaccination attitude/behavior groups (χ2(3) = 46.33; P < 0.0001). A higher level of trust was found among the PA/PB group (M = 5.71), followed by the PA/HB group (M = 5.08), and the HA/PB group (M = 4.31). The lowest level of trust was found among the HA/HB group (M = 3.74). However, insignificant difference was found between the vaccination attitude/behavior groups according to information seeking (χ2(3) = 0.59; P = 0.8987).

Table 4. The measured variables before participants’ exposure to the simulation according to vaccination attitude/behavior group using the Kruskal-Wallis test

In order to make all possible pairwise comparisons between attitudes/ behavior vaccination groups regarding trust level in the Ministry of Health, the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Flinger method (DSCF) was used (Table 5). A significant difference was found in trust in the Ministry of Health between the PA/PB and HA/PB groups (P = 0.0004), between the PA/PB and HA/HB groups (P < 0.0001), and between the HA/HB and PA/HB groups (P = 0.0289).

Table 5. Comparisons of level of trust in the Ministry of Health between groups using pairwise, 2-sided multiple comparison analysis (DSCF method)

Findings of the analysis of the measured variables after participants’ exposure to the simulation and the misinformation correction

According to the Kruskal-Wallis test results (Table 6), a significant difference was found between the different vaccination attitude/ behavior groups according to the reliability of the Ministry of Health’s response (χ2(3) = 31.56; P < 0.0001), satisfaction with the Ministry of Health’s response (χ2(3) = 25.25; P < 0.0001), and the level of help associated with the Ministry of Health’s tools in making a decision about vaccine (χ2(3) = 27.76; P < 0.0001).

Table 6. The difference in the measured variables after the misinformation correction according to the vaccination attitude/ behavior group using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the Pairwise, 2-sided Multiple Comparison Analysis (DSCF method)

A considerably higher average of reliability regarding the Ministry of Health’s response was found among the PA/PB group (M = 5.43), followed by the PA/HB group (M = 5.08), and was significantly higher than the HA/PB (M = 4.46) and HA/HB groups (M = 3.17).

Higher satisfaction with the Ministry of Health’s response means was found in the PA/PB group (M = 5.42); the lowest level was found in the HA/HB group (M = 3.26).

The DSCF method shows a significant difference in the reliability of the Ministry of Health’s response between the HA/PB and PA/PB (P = 0.0345) groups; the HA/PB and HA/HB groups (P = 0.0394); the PA/PB and HA/HB groups (P < 0.0001), and the HA/HB and PA/HB groups (P = 0.0205) (Table 6).

Regarding satisfaction with the Ministry of Health’s response, a significant difference was found between the PA/PB and HA/HB groups (P < 0.0001), and between the HA/HB and PA/HB groups (P = 0.0277) (Table 6).

In testing the difference between the groups according to the level of the help attributed to the Ministry of Health’s tools in deciding about vaccine, a significant difference was found only between the PA/PB and HA/HB groups (P < 0.0001), with a significantly higher mean among the PA/PB group (M = 5.10), compared to the HA/HB group (M = 3.04).

In testing the further information-seeking variable following the Ministry of Health’s response by a Chi-square test, no significant difference was found between the groups. Most participants in each group continued to seek further information following the Ministry of Health’s response (Table 7).

Table 7. Comparison of further information seeking following the Ministry of Health’s response using the Chi-Square test

Discussion

This study seeks to examine the responses of groups with different attitudes/ behavior regarding vaccination to the common and typical communication methods used by the Ministry of Health by simulating such a response on social media. In addition, this study aims to provide a better understanding of where the pro-vaccination with hesitant attitudes group is situated on the spectrum between the pro-attitude/ pro-behavior group and the hesitant-attitude/ hesitant-behavior group.

In the first stage, this study examined the component of trust in the Ministry of Health among groups with different attitudes/ behavior regarding vaccination. Previous studies indicate that trust in the vaccine delivery system is an essential factor in several explanatory models of vaccine hesitancy decision-making. According to these models, vaccine acceptance was found to be affected by distrust and lack of confidence in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, Reference Larson, Cooper, Eskola, Katz and Ratzan25,Reference Ozawa and Stack26 as well as in the healthcare system that delivers the vaccines. In addition, the individual’s knowledge and the information they receive about vaccines may also influence their vaccination decisions. Reference Dubé, Laberge and Guay1,Reference Peretti-Watel, Ward and Vergelys27,Reference Verger and Dubé28 The study findings show a difference in the level of trust in the Ministry of Health among the different groups. The highest level of trust in the Ministry of Health was found among the PA/PB (pro-attitudes/ pro-behavior) group, followed by the PA/HB (pro-attitudes/ hesitant-behavior), and the HA/PB (hesitant-attitudes/ pro-behavior) groups. The lowest level of trust was found among the HA/HB group (hesitant-attitudes/ hesitant-behavior). These findings indicate that groups with pro-vaccination attitudes have a higher level of trust in the Ministry of Health than groups with hesitant attitudes. This finding can be explained by the cognitive dissonance theory, which proposes that people seek psychological consistency about their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Inconsistency between attitudes and behavior is a primary type of cognitive dissonance, which may create psychological tension. This theory argues that some individuals resolve the dissonance by blindly trusting in whatever they want to believe, or by avoiding contradictory information that is likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance. Reference Festinger29,Reference Shahbari, Gesser-Edelsburg and Davidovitch30 Consistently, this study indicates that individuals with a higher level of trust in the Ministry of Health tend to express pro-vaccination attitudes and to be pro-vaccination – also as regards their behavior - in order to attain psychological consistency between their attitudes and behavior, and to avoid cognitive dissonance. Similarly, individuals with a lower level of trust in the Ministry of Health and have hesitant attitudes tend to also be hesitant in behavior to achieve a state of comfort. Another theory that reinforces the cognitive dissonance theory is Heider’s balance theory, which conceptualizes the cognitive consistency motive as a means of achieving psychological balance. Heider’s balance theory demonstrates a triadic relationship model, where 3 subjects are involved, and individuals seek to maintain a cognitive and emotional balance between 2 or more subjects, so that the ideas are in harmony and free from tension. Reference Shahbari, Gesser-Edelsburg and Davidovitch30–Reference Heider32 With respect to the findings of this study, the individual seeks to maintain a balance between his trust in the Ministry of Health, his trust in the effectiveness and safety of vaccines (which are promoted by the Ministry of Health), and his behavior regarding vaccination. Therefore, a higher level of trust among the groups with pro-vaccination attitudes leads to a higher level of trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccines (which are promoted by the Ministry of Health), eventually resulting in behavior that reflects vaccination acceptance, and vice versa.

In addition, these findings show that the pro-vaccination (in behavior) group members with hesitant attitudes do not trust the information they receive from the Ministry of Health. However, their trust issues have not yet had an impact on their behavior. This situation may change at some point, making these individuals hesitant in their behavior in the future. Reference Gesser-Edelsburg, Diamant, Hijazi and Mesch24–Reference Ozawa and Stack26 Therefore, health organizations should focus on building trust among the public as well as communicating clear and transparent information about vaccines.

Different interpretations may be offered to explain why a group expressing hesitant attitudes still chooses to vaccinate, despite their low level of trust in the health organization. For example, social norms were found to play a powerful role in vaccination-related decisions in several studies. According to these studies, individuals vaccinate their children or get vaccinated themselves because vaccination is considered a social norm; everybody is doing it thus it seems like the normal thing to do. Reference McLallen and Fishbein33–Reference Streefland, Chowdhury and Ramos-Jimenez35 For instance, a systematic review of vaccine uptake during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic indicates that the belief that family and friends have been vaccinated, or that others would want to be vaccinated, were associated with vaccination intention as well as actual uptake. Reference Bish, Yardley, Nicoll and Michie36

Another interpretation of the gap between hesitant attitudes and pro-vaccination behavior may be attributed to risk perception. Parents may choose to vaccinate their children despite their concerns and fears because of a low-risk perception of adverse effects due to positive experience with vaccines, low reported incidence of serious adverse effects after vaccination, or the high risk of disease infection. Some studies support this finding and suggest that an individual’s decision-making process regarding vaccines may be shaped by determinants such as the perceived risk of disease infection, Reference Mills, Jadad, Ross and Wilson37–Reference Cooper, Larson and Katz39 the perceived safety and efficacy of the vaccine, Reference Streefland40,Reference François, Duclos and Margolis41 as well as the social and financial costs associated with vaccination and disease infection. Reference Lau, Yeung and Choi42

The second stage of the study presented a simulation of the Ministry of Health’s common information communication transfer methods via social media. This simulation aimed to examine the response of vaccination attitudes/ behavior subgroups to this method of communication by measuring several variables, following participants’ exposure to the Ministry of Health’s response to a Facebook post posted by a mother. Examining the reliability of the Ministry of Health’s response variable indicates that subgroups with pro-vaccination attitudes, regardless of their behavior (pro/ hesitant), tend to perceive the Ministry of Health’s response as more reliable than subgroups with hesitant attitudes. This finding can be explained by a higher basic level of trust in the Ministry of Health among groups with pro-vaccination attitudes, as mentioned previously in this study. However, the hesitant behavior among the group with pro-vaccination attitudes may have arisen from reasons unrelated to attitudes such as physical availability, affordability and willingness to pay, geographical accessibility, ability to understand (language and health literacy), and appeal of immunization services’ affect uptake. 43 Therefore, the group with pro-vaccination attitudes and hesitant behavior may still have the intention to vaccinate their children or to get vaccinated themselves.

Another measured variable in the simulation is satisfaction with the Ministry of Health’s response. The findings point to a significant difference only between the group of pro-vaccination attitudes and behavior and the group of hesitant attitudes and behavior. This finding also indicates that all groups had a similar satisfaction level, and respectively strengthens the claim that the hesitant-attitudes/pro-behavior group is situated in the middle of the spectrum - between the pro-attitudes/pro-behavior group and the hesitant-attitudes/hesitant-behavior group. By following the aforementioned findings, this group may turn into one of the subgroups situated at the ends of the spectrum. Therefore, these findings predict that all groups will seek further information.

Consistent with the above findings, this study indicates that most participants in all 4 vaccination groups reported that they would continue seeking further information, even after reading the Ministry of Health’s response to the post on social media. In other words, even the pro-vaccination attitudes and behavior group (PA/PB) finds the information they receive from the Ministry of Health insufficient. Similarly, previous studies found that information insufficiency and untrustworthiness are positively associated with further information seeking, Reference Griffin, Yang and Ter Huurne44–Reference Griffin, Neuwirth, Dunwoody and Giese48 and encourage the public to search for further information from other information sources, Reference Griffin, Dunwoody and Yang49 apart from that of the health organization itself. Moreover, previous studies also found that information seeking may represent an initial step in changing actual behavior, Reference Galea50 as well as improving the degree of trust in information sources about vaccination. Reference Elran, Yaari and Glazer51 Therefore, it is crucial for health organizations to present sufficient information addressing the fears, concerns, and questions of all the vaccination subgroups in order to gain the public’s trust. Reference Gesser-Edelsburg20

In summary, the study findings emphasize the importance of trust as a central component in shaping the public’s attitudes and behaviors. In this study, trust was found to be associated with the public’s perception of the reliability of the health organization as an information source, and satisfaction regarding the health organization’s communication methods and responses. Therefore, it is important for health organizations to gain the public’s trust, especially that of pro-vaccination groups with hesitant attitudes, while addressing the public’s fears and concerns.

Limitations

Although the study’s sample is representative, only those participants who participated by choice were included. Therefore, the participants’ recruitment may be a study limitation and an indicator of selection bias.

It is also important to note that this study was conducted before the COVID-19 outbreak in Israel. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccine hesitancy phenomenon became more widespread. Many studies have reported a pattern of increasing doubts about the COVID-19 vaccine’s safety and effectiveness. Reference Anakpo and Mishi52–Reference Adhikari and Cheah54 This study points to a further potential expansion of vaccine hesitancy due to the gap between attitudes and behavior among individuals with hesitant attitudes and pro-vaccination behavior. Therefore, future studies should continue to investigate the phenomenon of vaccine hesitancy and explore how the COVID-19 outbreak has increased vaccine hesitancy. In addition, health organizations have to deal with, correct, or respond to a vast amount of information on social media, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, further studies should be conducted to develop effective ways for health organizations to communicate and correct information which, as this study found, obviously affect the public’s trust.

Conclusions

Trust plays a central role in shaping the public’s behaviors and attitudes, and mediates between several determinants such as seeking further information, and satisfaction with and reliability of the health organization. Therefore, health organizations need to foster trustworthiness among all the groups regarding vaccination, especially pro-vaccination individuals with hesitant attitudes who may eventually become hesitant also in behavior. In order to gain the public’s trust, health organizations are required to change their traditional communication methods and adopt a new communication strategy based on communicating transparent and complete information, while addressing the public’s fears and concerns.

Authors’ contribution

Conception and design of the work: RH and AG-E; data collection: RH; data analysis and interpretation: RH and AG-E; drafting the article: RH and AG-E; critical revision of the article: AG-E and GM; final approval of the version to be published: RH, AG-E, and GM.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding

The authors declare none.

Abbreviations

COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease of 2019; Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Flinger method, DSCF; hesitant-attitude/ hesitant-behavior, HA/HB; hesitant-attitude/ pro-behavior, HA/PB; pro-attitude/ hesitant-behavior, PA/HB; pro-attitude/ pro-behavior: PA/PB.