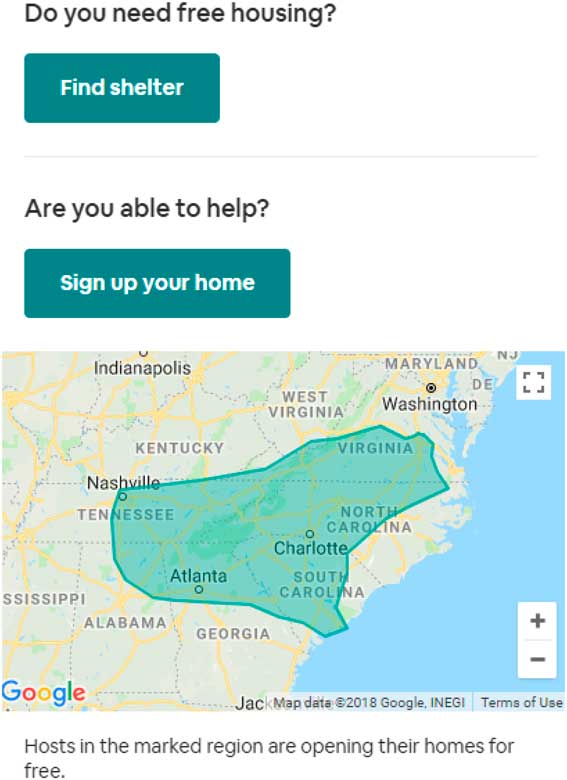

Predisaster and postdisaster evacuation planning is extremely important to safeguard life, both human and animal. In the aftermath of hurricanes Florence and Harvey, Airbnb offered a website on which a user could look for a home away from home at no cost for “displaced neighbors” and “relief workers deployed to help” (Figure 1). 1 I, too, would rather choose a home than a medical shelter to sleep in during trying times. The challenge is keeping track of evacuees from a public health and medical perspective and linking these displaced populations to available resources.

Figure 1 Screenshot of Airbnb Website after Hurricane Florence (September 24, 2018)

Under the Emergency Support Function #8—Public Health and Medical Services Annex, many agencies come together to acquire and assess the needs of the impacted areas. During the response to Hurricane Harvey, the challenge was identifying “pop up shelters” that would house displaced individuals, such as those in churches or people’s homes. Many displaced persons did not want to leave their homes or get bused to a large city 2 or 3 hours away, and thus Airbnb was an attractive alternative.

Our first responders are trained to recognize and triage medical patients in need of urgent care. Those not injured or without any immediate or visible medical need are sent to general population shelters; however, many of these evacuees may need uninterrupted treatment for various chronic conditions. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 2 adults in the United States has a chronic disease, and 1 in 4 adults has 2 or more. 2 The leading causes of death and disability in the United States are heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, which are also the drivers of the $2.7 trillion in annual health care costs. 2

Working as a medical regional director during the Hurricane Harvey response, I found it both challenging to direct my team and uplifting to see how many people wanted to help their neighbors. The agency responsible for mass care sheltering is the American Red Cross. The role of the Department of State Health Services, among many things, is to conduct epidemiologic surveillance in shelters with the aim of containing outbreaks and preventing further spread of disease. If several individuals in a shelter test positive for the flu, for example, the Department of State Health Services would identify causes and find ways to limit the spread of the disease through vaccination, education about handwashing, and isolation of sick patients. The option for evacuees to use Airbnb, though well intended, does add another layer of difficulty to the already challenging problem of disease surveillance in these displaced populations that are located outside of official state shelters.

Novel sheltering options represent an opportunity for public health and disaster response professionals globally to grow capacity and develop partnerships and innovative ways to connect people to services they need. A changing definition for shelter and the increased medical complexity of displaced populations will require professionals to think out of the box and further identify ways to help communities better prepare for the next disaster.