Introduction

Negative maternal mental health during pregnancy, namely depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms, have been consistently associated with internalizing, externalizing, and total psychiatric problems in children (Lahti et al., Reference Lahti, Savolainen, Tuovinen, Pesonen, Lahti, Heinonen, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie and Räikkönen2017; MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, Kingsbury, Mahedy, Evans and Colman2018; Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Oatley, Racine, Fearon, Schumacher, Akbari, Cooke and Tarabulsy2018; O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Glover, Barker and O’Connor2014; Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Obst, Teague, Rossen, Spry, MacDonald, Sunderland, Olsson, Youssef and Hutchinson2020; Van den Bergh et al., Reference Van den Bergh, van den Heuvel, Lahti, Braeken, de Rooij, Entringer, Hoyer, Roseboom, Räikkönen, King and Schwab2020). These associations persist throughout childhood and adolescence (O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Glover, Barker and O’Connor2014) and extend also to mental and behavioral disorders in children (Capron et al., Reference Capron, Glover, Pearson, Evans, O’Connor, Stein, Murphy and Ramchandani2015; Tuovinen et al., Reference Tuovinen, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Girchenko, Heinonen, Lahti, Reynolds, Hämäläinen, Villa, Kajantie, Laivuor and Raikkonen2021).

Despite that the World Health Organization has acknowledged the role of positive mental health as an important contributor to psychological well-being (World Health Organization, 2004), a view that has been echoed more recently by many experts (e.g., Henrichs & Witteveen, Reference Henrichs and Witteveen2022; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020), less attention has been devoted to the potential benefits that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy, such as positive emotions and perceived social support, might have for mental health in children. Positive mental health can be further conceptualized as two correlated but distinct subdomains of hedonic well-being and eudaimonic well-being (Joshanloo, Reference Joshanloo2016; Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001). Hedonic well-being encompasses positive affect and life satisfaction, while eudaimonic well-being encompasses aspects of self-realization such as self-acceptance, autonomy, mastery, and pursuing life-goals (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002; Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010). Additionally, positive mental health comprises social well-being such as social integration, contribution, coherence, actualization, and acceptance (Keyes, Reference Keyes1998; Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010). Positive and negative mental health, although inversely correlated, are independent constructs that can be seen as two separate continua (Keyes, Reference Keyes2002; Moeller et al., Reference Moeller, Ivcevic, Brackett and White2018; Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Fonseca, Pereira and Canavarro2021; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017, Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020; Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Dienberg Love, Urry, Muller, Rosenkranz, Friedman, Davidson and Singer2006; Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010) that show distinct antecedents (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Fonseca, Pereira and Canavarro2021; Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010) and biological correlates (Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Dienberg Love, Urry, Muller, Rosenkranz, Friedman, Davidson and Singer2006), and may also co-occur (Keyes, Reference Keyes2002; Moeller et al., Reference Moeller, Ivcevic, Brackett and White2018). Therefore, mental health does not merely indicate the absence of mental illness (Westerhof & Keyes, Reference Westerhof and Keyes2010; World Health Organization, 2004). Hence, studying the effects of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on child outcomes both independently and in relation to co-occurring negative maternal mental health is essential, and may contribute to promoting maternal mental health during pregnancy and developmental outcomes in children (Henrichs & Witteveen, Reference Henrichs and Witteveen2022; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020).

One prospective birth cohort study in Finnish mothers and their children has recently contributed to this gap in the literature (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022). In that study, positive maternal mental health during pregnancy was associated with lower hazards of mental and behavioral disorders in children followed up from birth to 8.4−12.8 years, and this association was independent of maternal depressive symptoms and/or mental disorders before or during pregnancy (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022).

Whereas mental and behavioral disorders represent the more severe end of the spectrum of psychiatric problems, we know of only two studies examining whether positive maternal mental health during pregnancy is associated with dimensionally assessed psychiatric problems in children (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017). Phua and colleagues (2017) investigated the association between positive maternal mood reported at 26 gestational weeks and infant behavior at 12−18 months among Singaporean mother–infant dyads. Findings were inconsistent, showing that positive maternal mood during pregnancy was associated with lower levels of autism symptoms, but higher levels of peer aggression, whereas no association was found with other internalizing or externalizing problems in infants (Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017). Clayborne and colleagues (2022), in turn, reported that in a Norwegian cohort of mother–child dyads, maternal self-efficacy at 30 gestational weeks was associated with lower internalizing and externalizing problems among girls but not boys at 5 years of age. Furthermore, the association between maternal stress during pregnancy and internalizing and externalizing problems among girls was attenuated among mothers with higher self-efficacy during pregnancy (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022).

To our knowledge, no earlier study has investigated whether possible associations of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy with lower psychiatric problems in children persist beyond early childhood, and whether higher positive maternal mental health during pregnancy is associated with how children’s psychiatric problem levels change from early childhood to late childhood when the incidence of psychiatric problems rises (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2021). It also remains unexplored whether the possible associations of positive maternal mental health and lower psychiatric problems in children are independent of the negative effects of negative maternal mental health such as depressive symptoms and mental disorders, and/or whether positive maternal mental health mitigates the effects of negative maternal mental health during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems. We are also not aware of studies which would have examined whether positive maternal mental health during offspring’s childhood mediates the effects of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on child mental health.

To address these critical gaps in knowledge, we investigated the following study questions: (1) is positive maternal mental health composite score during pregnancy, generated based on biweekly reports of positive mood, curiosity, and social support, associated with lower levels of psychiatric problems and with change in psychiatric problems among children from early childhood (1.9−5.9 years) to late childhood (7.1−12.1 years), and are these associations independent of negative maternal mental health; (2) does positive maternal mental health during pregnancy mitigate the effects of negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems and their change from early childhood to late childhood; (3) does positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up mediate the effects of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems; and (4) does child sex moderate the effects of positive maternal mental health, since previous literature has implicated that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy may confer benefits particularly for girls (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022).

Materials and methods

Participants

Our study cohort, the prospective Prediction and Prevention of Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction (PREDO) study (Girchenko et al., Reference Girchenko, Lahti, Tuovinen, Savolainen, Lahti, Binder, Reynolds, Entringer, Buss, Wadhwa, Hämäläinen, Kajantie, Pesonen, Villa, Laivuori and Räikkönen2017), recruited pregnant women during their first ultrasound screening visit between 12 + 0 and 13 + 6 gestational weeks+days at ten study hospitals in Southern and Eastern Finland. Of the recruited women, 4777 gave birth to a singleton live child between 2006 and 2010. Of this original cohort, 1079 (22.6%) were recruited based on a known risk factor status for preeclampsia/intrauterine growth restriction, and 3698 (77.4%) were recruited regardless of the risk status. Participating mother–child dyads in the whole PREDO cohort were similar to the Finnish population regarding key birth outcomes and the prevalence of gestational diabetes; however, the participating mothers were slightly older and more often multiparous, obese and with hypertensive pregnancy disorders in current pregnancy, and smoked less often throughout their pregnancies (Girchenko et al., Reference Girchenko, Lahti, Tuovinen, Savolainen, Lahti, Binder, Reynolds, Entringer, Buss, Wadhwa, Hämäläinen, Kajantie, Pesonen, Villa, Laivuori and Räikkönen2017).

Subsequently, three women withdrew their consent for the study. Of the 4774 participating women, 3402 (71.3%) reported their positive and negative mental health biweekly throughout pregnancy. In 2011−2012, 4586 mother–child dyads of the original cohort that could be traced were invited to a follow-up including a questionnaire on child psychiatric problems. Of the 3402 mothers who had completed the mental health questionnaires during pregnancy, 2296 (67.5%) provided follow-up data at the child’s age of 1.9−5.9 years (early childhood; median 3.5 years, interquartile range (IQR) 3.0−4.1 years). In 2016−2018, 4505 mother–child dyads with available contact information were again invited to a follow-up. At this follow-up, 2001 (58.8%) of the 3402 mothers who had completed the pregnancy questionnaire provided follow-up data at the child’s age of 7.1−12.1 years (late childhood; median 9.4 years, IQR 8.9−10.1 years). Altogether, 2636 mother–child dyads provided data in at least one of the child follow-ups and 1661 provided data in both, with the median length between the follow-ups being 6.05 years (IQR 5.87−6.13 years).

Compared to non-participants of the initial PREDO cohort, the mothers providing data in either of the child follow-ups were older, more often with a higher education level, primiparous, married or cohabiting, reported more often substance use during early pregnancy, and were less likely to have cardio-metabolic conditions during pregnancy or diagnosed mental disorders during their lifetime (Supplementary Table 1 in the Appendix).

The PREDO study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. All participating women signed written informed consents, enabling the linkage of data with nationwide register data for them and their children.

Measures

Positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and in the late childhood follow-up

Mothers reported their positive mental health with biweekly paper questionnaires up to 14 times throughout pregnancy, from gestational weeks 12−13 to 38−39/delivery, and again once at the child’s age of 7.1−12.1 years (late childhood). The positive affect scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) and the Curiosity scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, state version (STAI) (Spielberger, 1983) were used to assess positive emotions. The PANAS comprises 10 positive affect items (e.g. “enthusiastic”, “inspired”) rated on a 5-point scale according to how strongly the respondent currently experiences the affect (from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (5)), thus ranging from 0 to 50. The STAI Curiosity scale comprises 10 positively worded items (e.g. “I feel calm”, “I feel self-confident”) rated similarly on a 4-point scale (from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (4)), thus ranging from 10 to 40 (Spielberger & Reheiser, Reference Spielberger and Reheiser2009).

The PANAS scale has been described to reflect feelings of enthusiasm, activeness, alertness, and high energy (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) and to measure hedonic well-being (Ryff et al., Reference Ryff, Dienberg Love, Urry, Muller, Rosenkranz, Friedman, Davidson and Singer2006), whereas the STAI Curiosity scale focuses on general well-being, contentment, self-confidence, and interest in exploratory behavior (Kvaal et al., Reference Kvaal, Laake and Engedal2001; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017; Spielberger & Reheiser, Reference Spielberger and Reheiser2009), and hence reflects both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. In addition, to assess perceived social support as an aspect of social well-being, we used a visual analog scale (VAS) in which the mothers marked how much support they felt they had received from others during the past two weeks (from “not at all” (lower end) to “very much” (higher end)).

Previous evidence shows that the PANAS and the STAI Curiosity scales have good psychometric properties (Crawford & Henry, Reference Crawford and Henry2004; Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022; Sinesi et al., Reference Sinesi, Maxwell, O’Carroll and Cheyne2019; Spielberger, 1983; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988). In our sample, the scales showed good internal consistencies, α=.91−.94 for PANAS and α=.94−.95 for STAI Curiosity across pregnancy. Evidence also shows that PANAS, STAI, and VAS all show high continuity throughout pregnancy (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022); also in our study sample, the scales showed high consistency across pregnancy (r = 0.47−0.74 for PANAS, r = 0.45−0.69 for STAI Curiosity, and r = 0.39−0.76 for VAS between different assessments). Thus, we calculated pregnancy-trimester-weighted mean scores across all available observations during pregnancy (Pesonen et al., Reference Pesonen, Lahti, Kuusinen, Tuovinen, Villa, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Kajantie and Räikkönen2016). The scales have also been shown to be highly interrelated and to form a single principal component (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022; Verner et al., Reference Verner, Epel, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Kajantie, Buss, Lin, Blackburn, Räikkönen, Wadhwa and Entringer2021). Similarly to the approach used in these previous studies, we generated principal component scores of positive maternal mental health separately for the pregnancy and late childhood assessments, described in detail in the Statistical analyses section.

Negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy and until early childhood and late childhood follow-ups

Simultaneously to completing the questionnaires addressing positive mental health during pregnancy, the mothers assessed their depressive symptoms with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). The CES-D comprises 20 items that are rated from none (0) to all (3) of the time during the past week. The total score can range from 0 to 60, higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The CES-D has excellent psychometric properties (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), including among pregnant women (Lahti et al., Reference Lahti, Savolainen, Tuovinen, Pesonen, Lahti, Heinonen, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie and Räikkönen2017; Nast et al., Reference Nast, Bolten, Meinlschmidt and Hellhammer2013). In our sample, CES-D showed good internal consistency, α=.89−.92 across pregnancy. As the CES-D scores show high continuity throughout pregnancy (Lahti et al., Reference Lahti, Savolainen, Tuovinen, Pesonen, Lahti, Heinonen, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie and Räikkönen2017), we calculated a pregnancy-trimester-weighted mean score across all available observations (Pesonen et al., Reference Pesonen, Lahti, Kuusinen, Tuovinen, Villa, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Kajantie and Räikkönen2016). Previous research suggests that a cutoff score of 16 identifies individuals at risk for clinically relevant depressive symptoms with high sensitivity (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977; Vilagut et al., Reference Vilagut, Forero, Barbaglia and Alonso2016).

We identified maternal lifetime mental disorder diagnoses until (i) childbirth, (ii) the early childhood, and (iii) late childhood follow-ups from the Finnish nationwide Care Register for Health Care (HILMO), which is a validated research tool in general and particularly for research on mental disorders (Sund, Reference Sund2012). The HILMO diagnoses are based on the International Classification of Diseases 8th (ICD-8; codes 290−315) and 9th (ICD-9; codes 290−319) Revisions and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th (ICD-10; codes F00−F99) Revision. Primary and subsidiary diagnoses of all hospital treatments in Finland were available from 1969 and of all outpatient treatments in public specialized medical care in Finland were available from 1998. Our diagnostic phenotype was thus any lifetime diagnosed mental disorder, identified from the HILMO register with the abovementioned diagnostic codes.

In our analyses where we addressed whether the associations between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and child psychiatric problems were independent of negative maternal mental health, we generated a combined dichotomous negative mental health variable which identified mothers with clinically relevant depressive symptoms (CES-D≥16) during pregnancy and/or those with a lifetime diagnosed mental disorder by the early childhood or late childhood follow-up (yes vs. no). In the analyses in which we tested whether positive maternal mental health mitigated the effects of negative maternal mental health on child psychiatric problems and their change, we examined maternal CES-D scores during pregnancy as a continuous variable and identified mental disorder diagnoses until childbirth, and studied them separately and also using the combination variable (CES-D≥16 and/or mental disorder diagnosis, yes vs. no).

Women who were diagnosed with mental disorders by the late childhood follow-up reported significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms during pregnancy (mean difference 0.58 SD units; p < .001) and had higher odds of reporting clinically relevant depressive symptoms during pregnancy (odds ratio 2.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.21−3.51, p < .001).

Psychiatric problems in children

Mothers assessed their children’s psychiatric problems with age-appropriate versions of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) at two follow-ups: CBCL for ages 1½−5 years (CBCL/1½−5) (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000) at the early childhood follow-up and CBCL for ages 6−18 years (CBCL/6−18) (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001) at the late childhood follow-up. The scales comprise 99 and 119 caregiver-rated problems, respectively, ranging on a three-point scale from “not true” (0) to “very true/often true” (2). Both scale versions show excellent validity and reliability (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000; Kristensen et al., Reference Kristensen, Henriksen and Bilenberg2010; Rescorla, Reference Rescorla2005).

CBCL scores were converted to age- and sex-standardized t-scores according to the manuals, enabling us to investigate change in psychiatric problems across the two follow-ups. Both CBCL versions yield three main scales, namely total, internalizing, and externalizing problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2001, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000). We used total problems in children as our main outcome and the subscales of internalizing and externalizing problems as our secondary outcomes. According to Achenbach and colleagues, internalizing problems reflect emotional reactivity, anxiety, depression, withdrawal, and somatic complaints, and externalizing problems reflect impulsivity, aggression, and rule-breaking behavior (Achenbach et al., Reference Achenbach, Ivanova, Rescorla, Turner and Althoff2016; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000). The total problems scale encompasses internalizing and externalizing problems and additional scales such as attention and social problems, thus capturing general psychopathology (Achenbach et al., Reference Achenbach, Ivanova, Rescorla, Turner and Althoff2016; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000). The internal consistencies of the total, internalizing, and externalizing problem scales were α = .94, α = .83, and α = .90 in the early childhood follow-up and α = .95, α = .83, and α = .91 in the late childhood follow-up, respectively.

Covariates

Mother-related covariates included age at delivery (years), parity (primiparous/multiparous), family structure (cohabiting or married/single parent), cardio-metabolic pregnancy conditions (none / early pregnancy body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25kg/m2, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension or unspecified hypertension in current pregnancy [ICD-10: I10, O10–O11, O13−O16], and/or type 1 or type 2 diabetes or gestational diabetes in current pregnancy [ICD-10: E08−E14, O24] / hypertension or gestational diabetes only before current pregnancy or early pregnancy BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), and smoking (no smoking/smoked in early pregnancy). Child-related covariates included sex, age at follow-up assessment, gestational age (weeks), and birth weight (grams). Data on these covariates were derived from the Finnish nationwide Medical Birth Register (Gissler et al., Reference Gissler, Louhiala and Hemminki1997), medical records, and/or the HILMO.

In addition, two covariates used mother-reported data: maternal education level and alcohol use in early pregnancy. Mothers reported on their highest achieved education level in early pregnancy and at both follow-ups, and the most recently reported education level (basic or secondary/lower tertiary/upper tertiary) was used in the analyses. Mothers also reported their alcohol consumption in early pregnancy (yes/no). Maternal smoking and alcohol use during early pregnancy were combined into a variable indicating any substance use in early pregnancy (yes/no).

Statistical analyses

Before proceeding to analyses testing associations between positive maternal mental health and child psychiatric problems in early childhood and late childhood, we created weighted principal component scores of the PANAS, STAI curiosity, and VAS scales, which were highly interrelated during pregnancy (r = .40−.67, p < .001) and in late childhood (r = .29−.61, p < .001). The principal component scores were created to reduce the dimensionality of the data, while retaining maximum variance and statistical power. We used eigenvalue criterion 1 to extract the principal components. In line with previous findings (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022; Verner et al., Reference Verner, Epel, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Kajantie, Buss, Lin, Blackburn, Räikkönen, Wadhwa and Entringer2021), one component explained 66.7% (eigenvalue 2.0) and 60.7% (eigenvalue 1.8) of the total variance during pregnancy and in late childhood, respectively. The scales showed high loadings on these components both during pregnancy (loadings 0.87, 0.87 and 0.70 for PANAS, STAI Curiosity and VAS, respectively) and in offspring’s late childhood (loadings 0.85, 0.85 and 0.61 for PANAS, STAI Curiosity and VAS, respectively).

The positive maternal mental health composite scores and child psychiatric problem scores followed normal distributions, whereas continuous CES-D scores were square root transformed to account for skewness. The continuous variables of positive and negative maternal mental health are expressed in standard deviation units to facilitate the interpretation of effect sizes.

The statistical methods applied for each study question are described below, numbered according to the study questions presented in the Introduction.

1) First, associations between positive maternal mental health composite score during pregnancy and total psychiatric problems in children in early childhood (1.9−5.9 years) and in late childhood (7.1−12.1 years) were investigated with linear regression analyses. These analyses were adjusted for child sex and age at assessment (Model 1) and additionally for child birth weight and gestational age and maternal parity, marital status, age at childbirth, education level, substance use, cardio-metabolic conditions, and the combined negative maternal mental health variable which identified negative mental health by the early childhood and late childhood follow-ups (Model 2). Similarly, we investigated associations with the secondary outcomes of internalizing and externalizing problems, adjusting for the same covariates.

To study whether positive maternal mental health during pregnancy was associated with change in the children’s total psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood, we used linear mixed models for longitudinal data. In these analyses, only children with both CBCL assessments available (n = 1661) were included. Total psychiatric problems in early childhood and in late childhood represented the within-person outcome, positive maternal mental health composite score was the between-person predictor, child age at the two follow-ups the within-person predictor, and their interaction addressed the question of change. Where significant interactions between positive maternal mental health and child age occurred, we ran two separate sub-analyses, which studied change in psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood among children of mothers reporting lower (below median) and higher (at/above median) levels of positive mental health. We used compound symmetry covariance structure for our repeated within-person predictor, which allows for correlation between the two separate measurements, and adjusted these analyses for child sex.

2) To investigate whether the effects of positive maternal mental health mitigated the effects of negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems, we ran linear regression analyses with the child’s total psychiatric problems in early childhood and late childhood as the outcomes and included an interaction term of positive maternal mental health and negative maternal mental health. We ran three separate interaction models in which CES-D scores were treated as continuous, mental disorders as dichotomous, and combined negative maternal mental health as dichotomous. We then conducted subgroup analyses in which we studied the effects of positive maternal mental health among children of mothers with and without negative mental health before or during pregnancy. These analyses were adjusted for child sex and age.

To further investigate whether positive maternal mental health mitigated the effects of negative maternal mental health on the change in psychiatric problems among children from early childhood to late childhood, we applied linear mixed models as described above and included three-way interaction terms between child age, positive maternal mental health, and negative maternal mental health. We again ran three separate interaction models in which CES-D scores were treated as continuous, mental disorders as dichotomous, and combined negative maternal mental health as dichotomous. We then investigated the change in psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood among children of mothers reporting lower (below median) and higher (at/above median) levels of positive mental health in the subgroups of mothers with and without negative mental health before or during pregnancy.

3) We also investigated whether positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up mediated the association between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and the child’s total psychiatric problems in late childhood. Mediation analyses were conducted using the Process Macro 3.5.3 for SPSS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2022), a regression-based method for observed variables that uses bootstrapping with 5000 resamples with replacement and bias corrected confidence intervals to assess the presence of an indirect effect via a mediator (Abu-Bader & Jones, Reference Abu-Bader and Jones2021; Hayes & Scharkow, Reference Hayes and Scharkow2013; Hayes, Reference Hayes2009, Reference Hayes2022; Igartua & Hayes, Reference Igartua and Hayes2021). The benefits of the mediation analysis method described in the Process macro include robustness regarding statistical assumptions, higher study power and a lower risk of falsely rejecting the null hypothesis (Abu-Bader & Jones, Reference Abu-Bader and Jones2021; Hayes & Scharkow, Reference Hayes and Scharkow2013; Hayes, Reference Hayes2009; Igartua & Hayes, Reference Igartua and Hayes2021), and this method produces essentially identical results with structural equation modeling mediation models in analyses including solely observed variables (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Montoya and Rockwood2017; Pek & Hoyle, Reference Pek and Hoyle2016).

4) Finally, since an earlier study found sex specific associations between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and psychiatric problems in children (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022), we also investigated whether any interactions occurred between positive maternal mental health and child sex when predicting child total problems in linear regression analyses.

As missing data on covariates was minimal (Table 1; max. 0.2% of data missing for the covariates), a complete-case approach was used. A two-sided p-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 29 and with Stata 17.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants with available data for the follow-up at early childhood (child age 1.9–5.9 years) and at late childhood (child age 7.1–12.1 years), and of the participants with available data for both follow-ups

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; mm = millimeters; PANAS = positive and negative affect schedule; SD = standard deviation; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; VAS = visual analog scale.

a Cardio-metabolic pregnancy conditions included early pregnancy body mass index [BMI]≥25kg/m2, chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational hypertension or unspecified hypertension in current pregnancy [ICD-10: I1, 010-011, O13-O16], and/or type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes [ICD-10: E08-E14, O24].

b All mental and behavioral disorder diagnoses classified using the International Classification of Diseases, 8th (ICD-8; codes 290-315) and 9th (ICD-9; codes 290-319) Revisions and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th (ICD-10) Revision (codes F00-F99).

c Psychiatric problems at each follow-up and the mean of the two follow-ups for those with available data for both follow-ups.

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of the mother–child dyads participating in the follow-up in early childhood (1.9−5.9 years) and late childhood (7.1−12.1 years), and of the mother–child dyads participating in both follow-ups. Psychiatric problems among children showed continuity over the two follow-ups (correlations for CBCL t-scores r = .55 for total problems, r = .44 for internalizing problems, and r = .51 for externalizing problems; p < .001 for all correlations). Supplementary Table 2 in the Appendix shows associations of the covariates with total problems in children in early childhood and in late childhood. Children of younger, primiparous and single mothers, of mothers with lower education level and substance use, as well as children who were younger, boys, and with lower birth weight, scored higher on total psychiatric problems in early childhood and/or late childhood. Supplementary Table 3 shows the associations of negative maternal mental health with total problems in children in early childhood and in late childhood. Children of mothers with depressive symptoms during pregnancy, mental disorders before or during pregnancy, or clinically relevant depressive symptoms and/or mental disorders by childhood follow-up scored higher on total psychiatric problems. Moreover, Supplementary Table 4 shows that mothers who reported clinically relevant depressive symptoms during pregnancy and who had mental disorders before or during pregnancy also scored lower on the positive mental health composite score during pregnancy.

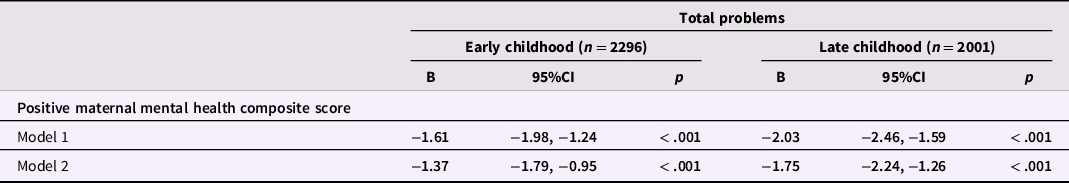

Positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and psychiatric problems in early childhood and in late childhood

Analyses addressing the first study questions showed that higher positive maternal mental health composite score during pregnancy was associated with lower total psychiatric problem t-scores in children at both follow-ups (Table 2). All associations were independent of covariates, including several sociodemographic characteristics as well as the combined negative maternal mental health variable. Supplementary Table 5 shows the associations of the independent variables and covariates with child psychiatric problems in the full Model 2. Supplementary Table 6 shows that the associations between positive maternal mental health and child psychiatric problems were similar for internalizing and externalizing problems.

Table 2. Associations between positive maternal mental health and total psychiatric problems among children in early childhood and in late childhood

CI = confidence interval.

Model 1 is adjusted for child sex and age at assessment of psychiatric problems.

Model 2 is adjusted for covariates of Model 1 and child’s birth weight and gestational age, maternal age, marital status, education level, parity, substance use during pregnancy, cardio-metabolic pregnancy conditions, and negative mental health, i.e., clinically relevant depressive symptoms (CES-D) during pregnancy and/or mental disorders by the child’s early childhood and late childhood follow-ups.

Linear mixed models showed that positive maternal mental health composite score interacted significantly with the age of the child at follow-up in predicting total psychiatric problems in children (B = −0.10, 95% CI −0.17, −0.02 for interaction; p = .01; Fig. 1). Subgroup analyses indicated that the total problems t-scores remained at a stably lower level from early childhood to late childhood among children of mothers with higher levels of positive mental health during pregnancy (composite score at or above median), whereas the t-scores were higher and increased among children of mothers with lower levels of positive mental health during pregnancy (composite score below median) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Change in total psychiatric problems t-scores from early childhood to late childhood among children of mothers with lower (below median) and higher (at or above median) levels of positive mental health composite score during pregnancy. Analyses are adjusted for child’s sex, and conducted among mother–child dyads with psychiatric problems data available at both follow-ups (n = 1661).

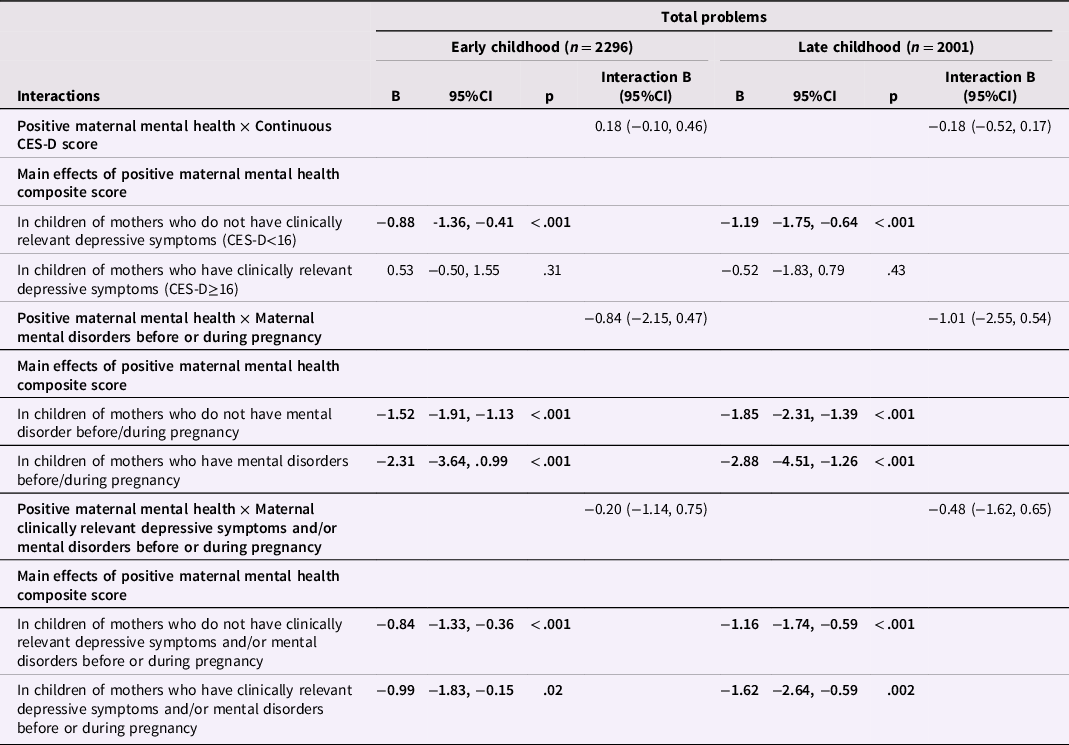

Mitigation of negative maternal mental health effects by positive maternal mental health

Analyses addressing the second study question showed that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy did not interact significantly with continuous CES-D scores, dichotomous variable of mental disorder diagnosis before or during pregnancy, or the combined dichotomous variable of negative mental health before and during pregnancy in predicting child total psychiatric problems in early childhood or in late childhood (p-values for all interactions > .21; Table 3). Table 3 shows that positive maternal mental health was associated with lower total psychiatric problems in children whose mothers had and did not have negative mental health before or during pregnancy, except in the subgroup of children whose mothers had clinically relevant depressive symptoms during pregnancy, in which subgroup the association was not significant.

Table 3. Interactions between positive maternal mental health composite score and negative maternal mental health, and main effects of positive maternal mental health composite score on child total psychiatric problems in the subgroups of mothers with and without negative mental health

CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale; CI = confidence interval.

Three-way interaction analyses addressing whether positive maternal mental health mitigated the effects of negative maternal mental health on the change in psychiatric problems showed a significant interaction between positive maternal mental health × continuous CES-D score during pregnancy × child age (Supplementary Table 7). Further analyses among mothers reporting clinically relevant depressive symptoms during pregnancy showed that in this subgroup, child total psychiatric problems did not increase if the mother reported higher levels of positive mental health during pregnancy, whereas they increased if the mother reported lower levels of positive mental health during pregnancy (Supplementary Figure 1, Panel A). Total problems did not increase from early childhood to late childhood in children of mothers with lower than clinically relevant depressive symptoms, regardless of whether the mother reported higher or lower positive mental health during pregnancy (Supplementary Figure 1, Panel B). There were no significant three-way interactions regarding other indicators of negative maternal mental health (Supplementary Table 7; Supplementary Figure 1, Panels C − F).

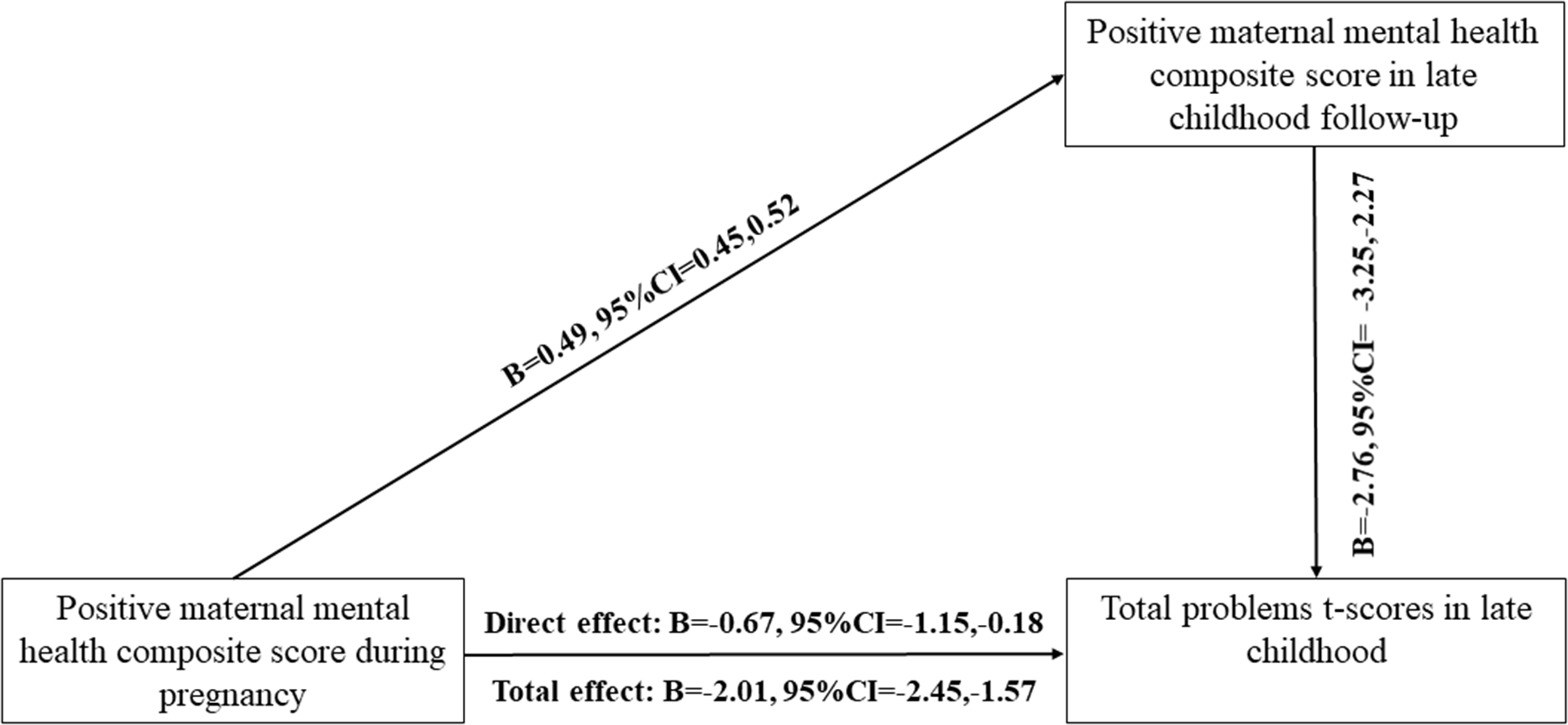

Positive maternal mental health in late childhood as a mediator

Before we proceeded to testing our third study question addressing mediation, we tested the associations between positive maternal mental health composite score measured during pregnancy and in the late childhood follow-up (unstandardized b = 0.49, 95% CI 0.45, 0.53; p < .001), and in the late childhood follow-up between the positive maternal mental health composite score and child total psychiatric problems (unstandardized b = −3.08, 95% CI −3.51, −2.65; p < .001). Both associations were significant.

Positive maternal mental health composite score in the late childhood follow-up partially mediated the association between the positive maternal mental health composite score during pregnancy and total psychiatric problems among children in late childhood (Fig. 2). The effect size proportion mediated was 66.7%.

Figure 2. Associations between positive maternal mental health composite score during pregnancy and child’s total psychiatric problems in late childhood are partially mediated by positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up (n = 1962).

Interactions with child sex

Analyses addressing the fourth study question showed that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and child sex showed no interactions on child total psychiatric problems in early childhood (all p-values ≥ .15) or in late childhood (all p-values ≥ .46; Supplementary Table 8). Supplementary Table 8 also shows that there were no such interactions either when we examined child internalizing and externalizing problems.

Discussion

In this prospective pregnancy cohort study among 2636 mother–child dyads, higher level of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy, defined as positive emotions, curiosity, and perceived social support, was associated with lower levels of total psychiatric problems among children both in early childhood and in late childhood. These associations were independent of negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy and/or by early childhood and late childhood. The associations were similar for child’s internalizing and externalizing problems. Total psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood remained stably lower among children whose mothers reported at or above median levels of positive mental health during pregnancy, whereas among children of mothers reporting below median levels of positive mental health during pregnancy, the psychiatric problem scores increased from early childhood to late childhood. The associations between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and lower total psychiatric problems in children were detected also among mothers with negative mental health before or during pregnancy. Furthermore, positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up mediated 66.7% of the effect of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on total psychiatric problems in late childhood. Taken together, these findings suggest that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy may have longitudinal benefits for all children, regardless of their exposure to negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy or in childhood, and that a large proportion of this benefit is mediated by positive maternal mental health continuing later in offspring’s childhood.

These findings are in line with an earlier Finnish study which reported that positive maternal mental health during pregnancy was associated with lower hazard ratios of mental and behavioral disorders in a follow-up from birth until 8.4−12.8 years and that these associations were independent of negative maternal mental health (Lähdepuro et al., Reference Lähdepuro, Lahti-Pulkkinen, Pyhälä, Tuovinen, Lahti, Heinonen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie, Girchenko and Räikkönen2022). The current results also correspond with those of a recent Norwegian study reporting an association between maternal self-efficacy during pregnancy and lower internalizing and externalizing problems at age 5 years, however, the earlier study reported the association only among girls (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022). Also only among girls, this earlier study demonstrated in line with our findings that the associations were independent of maternal stress during pregnancy (Clayborne et al., Reference Clayborne, Nilsen, Torvik, Gustavson, Bekkhus, Gilman, Khandaker, Fell and Colman2022). Our study did not detect sex differences in the associations.

Our findings are also partly in line with the Singaporean study reporting an association between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and lower autism symptoms in infants. In contrast to our findings, this previous study found no associations with infant internalizing and externalizing problems, except for a surprising association with higher peer aggression (Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017). The Singaporean study did not report whether associations were independent of or mitigated the effects of negative maternal mental health (Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee, Koh, Rifkin-Graboi, Daniels, Chen, Chong, Broekman, Magiati, Karnani, Pluess, Meaney, Agarwal, Biswas, Bong, Cai, Chan, Chan and Chee2017). In both of these previous studies, mothers reported their mental health only once during pregnancy, whereas our study covered the whole of pregnancy. Moreover, we followed up the children twice, in early childhood and in late childhood. It is possible that the associations between positive maternal mental health and psychiatric problems in children become more evident as the children mature, as the incidence of psychiatric problems, particularly clinically significant psychiatric problems becomes more evident when children reach later childhood (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2021). For example, the peak age of onset for neurodevelopmental and anxiety disorders is estimated to be 5.5 years, and the peak age of onset for mood disorders is 20.5 years (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Radua, Olivola, Croce, Soardo, Salazar de Pablo, Il Shin, Kirkbride, Jones, Kim, Kim, Carvalho, Seeman, Correll and Fusar-Poli2021).

The increasing prevalence of psychiatric problems according to the child’s age may also explain the increase in levels of total psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood in children of mothers with low positive mental health during pregnancy. This appeared to be the case, even though the total psychiatric problems scores were already significantly higher in early childhood compared with the scores of children of mothers with higher levels of positive mental health during pregnancy. Alternatively, this finding may also reflect continuity of low positive maternal mental health from pregnancy to childhood, which our study demonstrated, and hence accumulation of adversity.

Our findings on the lack of interaction effects between positive and negative maternal mental health suggest that the effects of positive maternal mental health are similar at different levels of negative maternal mental health. This indicates that positive maternal mental health may mitigate at least some of the effects of negative mental health on child psychiatric problems. Furthermore, our findings on the interaction between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and child age when predicting psychiatric problems among children of mothers with clinically relevant depressive symptoms suggest that positive maternal mental health may mitigate the effects of maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy on the increase in psychiatric problems from early childhood to late childhood. While interesting, this finding needs to be replicated in larger samples of women and their children.

High continuity of positive maternal mental health from pregnancy to the child’s late childhood was also reflected in our findings, which showed that positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up partially mediated the associations between higher levels of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and lower psychiatric problems in children. While earlier studies have shown that negative maternal mental health after pregnancy partly mediates the associations between negative maternal mental health during pregnancy and psychiatric problems in children (Hentges et al., Reference Hentges, Graham, Plamondon, Tough and Madigan2019; Lahti et al., Reference Lahti, Savolainen, Tuovinen, Pesonen, Lahti, Heinonen, Hämäläinen, Laivuori, Villa, Reynolds, Kajantie and Räikkönen2017), our study is to our knowledge the first to demonstrate that similar mediation is present also for positive maternal mental health. Even though positive maternal mental health in offspring’s late childhood mediated a sizeable proportion, 66.7%, of the effect of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems, this mediation was partial. Hence positive maternal mental health during pregnancy also had a significant direct effect on lower total psychiatric problems in children. This finding suggests that other mediating factors also play a part.

These other potential mediators include genetic factors that may underlie the associations between positive maternal mental health and child mental health (Neumann et al., Reference Neumann, Nolte, Pappa, Ahluwalia, Pettersson, Rodriguez, Whitehouse, van Beijsterveldt, Benyamin, Hammerschlag, Helmer, Karhunen, Krapohl, Lu, van der Most, Palviainen, St Pourcain, Seppälä and Suarez2022). However, we made adjustments for maternal mental disorders and concurrent positive maternal mental health, and positive maternal mental health during pregnancy showed effects that were independent of these factors. Epigenetic changes during pregnancy, referring to alterations in chromatin structure that regulate gene expression, may also link positive maternal mental health to child mental health. Evidence exists on epigenetic mechanisms underlying the association between negative maternal mental health during pregnancy and child mental health (Cao-Lei et al., Reference Cao-Lei, de Rooij, King, Matthews, Metz, Roseboom and Szyf2020; Monk et al., Reference Monk, Lugo-Candelas and Trumpff2019; Provençal et al., Reference Provençal, Arloth, Cattaneo, Anacker, Cattane, Wiechmann, Röh, Ködel, Klengel, Czamara, Müller, Lahti, Räikkönen, Pariante and Binder2020), but to our knowledge, no studies have investigated epigenetic changes associated with positive maternal mental health during pregnancy.

Positive maternal mental health during pregnancy may also reflect on the later caregiving environment of the child. Both negative and positive maternal mental health during pregnancy may contribute to the development of maternal bonding, care practices, and parenting behaviors (Le Bas et al., Reference Le Bas, Youssef, Macdonald, Mattick, Teague, Honan, McIntosh, Khor, Rossen, Elliott, Allsop, Burns, Olsson and Hutchinson2021; McManus et al., Reference McManus, Khalessi, Lin, Ashraf and Reich2017; Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020). Subsequent parenting may play a role in linking prenatal positive maternal mental health with child outcomes (Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020).

Positive mental health in the general population has shown several protective effects on public health, including decreased mortality and a lower risk of later psychopathology (Holt-Lunstad et al., Reference Holt-Lunstad, Smith and Layton2010; Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Dhingra and Simoes2010; Vos et al., Reference Vos, Abajobir, Abbafati, Abbas, Abate, Abd-Allah, Abdulle, Abebo, Abera, Aboyans, Abu-Raddad, Ackerman, Adamu, Adetokunboh, Afarideh, Afshin, Agarwal, Aggarwal and Agrawal2017). Some countries are already systematically screening for positive mental health among their residents (Office of National Statistics, 2023; Orpana et al., Reference Orpana, Vachon, Dykxhoorn, McRae and Jayaraman2016), and our findings suggest that similar screening measures of positive mental health would be beneficial among pregnant women. Our findings also suggest that maternal interventions during pregnancy that aim at supporting positive mental health may have beneficial effects and provide protection for the child’s mental health. These interventions may target maternal perceived social support, feelings of competence, physical health and active lifestyle, self-compassion, and resilience (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Fonseca, Pereira and Canavarro2021; Rodriguez-Ayllon et al., Reference Rodriguez-Ayllon, Acosta-Manzano, Coll-Risco, Romero-Gallardo, Borges-Cosic, Estévez-López and Aparicio2021; Varin et al., Reference Varin, Palladino, Orpana, Wong, Gheorghe, Lary and Baker2020). Interventions supporting positive maternal mental health already during pregnancy may also promote higher parenting self-efficacy and thus enhance positive parenting practices after the child’s birth (Phua et al., Reference Phua, Kee and Meaney2020). Further research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of such interventions on child mental health.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study included a large study sample, a prospective study design, and a follow-up extending to the offspring’s late childhood; to our knowledge, this is the longest follow-up to date on the effects of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on child psychiatric problems. Another major strength was that we followed up the children twice, in early childhood and in late childhood. We also used validated, age-appropriate questionnaires to assess child psychiatric problems, enabling us to investigate change in psychiatric problems across childhood. Positive and negative maternal mental health during pregnancy were also assessed with validated questionnaires, using biweekly assessments, thus adding to the reliability of assessment. We were also able to investigate whether the associations of positive maternal mental health were independent of co-occurring negative maternal mental health.

Our study also has limitations. First, the participants of the PREDO cohort live in a high-resource Nordic setting providing free-of-charge antenatal and well-baby clinic services for all women and children. Furthermore, loss to follow-up was selective as the participating mothers were more often highly educated, primiparous, married, or cohabiting, and less likely to smoke or to have cardio-metabolic conditions during pregnancy or diagnosed mental disorders during their lifetime. For example, over 70% of the participating mothers had at least a tertiary education level. This selective attrition may limit the generalizability of our findings; there is some evidence, for example, that positive mental health may be higher among individuals who are older and with higher education level (Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Shmotkin and Ryff2002). Also in our sample, mothers with the highest education level reported higher positive mental health during pregnancy than did mothers with the lowest education level (data not shown). When planning and implementing interventions to target positive maternal mental health during pregnancy, it should also be noted that women differing from our sample in these characteristics may differ in accessibility and adherence to these interventions.

Second, psychiatric problems in children were mother-assessed, and concurrent maternal mood may affect the mother’s assessment of their child’s symptoms. However, we accounted for positive maternal mental health at late childhood follow-up in the mediation analyses, and were thus able to at least partially account for possible bias that may relate to maternal mood at the time of reporting child psychiatric problems. Finally, positive maternal mental health at the late childhood follow-up and psychiatric problems in children were assessed concurrently, which limits our ability to make inferences about the direction of causality between positive maternal mental health in late childhood and co-occurring psychiatric problems in children (Pek & Hoyle, Reference Pek and Hoyle2016). Concurrent timing with the outcome variable is also against the strict definition of a mediating variable (Cole & Maxwell, Reference Cole and Maxwell2003). However, our mediation analysis does inform about both independent associations of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy with child psychiatric problems, the high continuity of positive maternal mental health across time, and the possible pathways through which positive maternal mental health during (and after) pregnancy may be associated with child behavior.

Conclusions

In this prospective pregnancy cohort study, higher levels of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy were associated with lower levels of total, internalizing, and externalizing psychiatric problems in children both in early childhood and in late childhood and these associations were independent of several sociodemographic factors and of negative maternal mental health before or during pregnancy or by early childhood and late childhood. Positive maternal mental health during pregnancy was also associated with change in total psychiatric problems in children from early childhood to late childhood: psychiatric problems increased only among children of mothers with low levels of positive mental health during pregnancy. The associations between positive maternal mental health during pregnancy and lower total psychiatric problems in children were detected among mothers with and without negative mental health before or during pregnancy. We also showed that positive maternal mental health in the late childhood follow-up partially mediated the effects of positive maternal mental health during pregnancy on psychiatric problems in children. Our findings underscore the importance of supporting positive maternal mental health during pregnancy in the efforts to prevent psychiatric problems among children.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423001244.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participating families for their valuable contribution to the ongoing cohort study.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (MLP, grant number 330206; KR; EK; KH, grant number 345057), European Union’s Horizon 2020 Award (KR, SC1-2016-RTD-733280 for RECAP), European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under grant agreement No 101057390 (HappyMums), European Commission Dynamics of Inequality Across the Life-course: structures and processes (DIAL: KR, No 724363 for PremLife), EVO (special state subsidy for research; KR), University of Helsinki Funds, Doctoral School of Psychology, Learning and Communication (AL), Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Orion Research Foundation, Emil Aaltonen Foundation, Finnish Medical Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Sigrid Juselius Foundation (EK), and Yrjö Jansson Foundation (KR).

Competing interests

None.