An estimated 10–15% of mothers experience postnatal depression, with those living in poverty and of ethnic minorities typically found to be at even greater risk of depressive symptoms in this critical life stage (Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Waldie, D’Souza, Peterson and Morton2016). In particular, a recent review of research with indigenuos mothers in the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand highlighted experiences of intergenerational trauma, systemic racism (including within the healthcare system), and disconnection from traditional cultural systems and supports; highlighting a need for research examining perinatal depression to include more diverse samples and longitudinal designs (Bowen et al., Reference Bowen, Duncan, Peacock, Bowen, Schwartz, Campbell and Muhajarine2014). There is evidence for longitudinal impacts of maternal depression on children’s social, emotional, and cognitive development (Kingston & Tough, Reference Kingston and Tough2014; Sanger et al., Reference Sanger, Iles, Andrew and Ramchandani2015). Differences in parent behaviors and interactions is one potentially modifiable pathway that may explain the developmental impacts of depression on offspring (Goodman & Gotlib, Reference Goodman and Gotlib1999). For example, mothers with higher depression symptoms are consistently shown to engage in less warm, responsive, and stimulating interactions with their infants and children (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). Understanding the particular mechanisms by which maternal depression relates to specific child developmental outcomes provides critical information about future prevention and intervention targets. In addition, this understanding must also be specific for particular population contexts; as the sociocultural, economic, and environmental conditions within countries are also important for an understanding of maternal mental wellbeing, parent-child interactions, and language development (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019).

Maternal depressive symptoms

The experience of maternal depressed mood during the perinatal and infancy period can be conceptualized in different ways. Many women may experience “postpartum blues,” lasting days, whereas others may experience more severe and persistent postnatal depression symptoms that meet criteria for a major depressive disorder (Räisänen et al., Reference Räisänen, Lehto, Nielsen, Gissler, Kramer and Heinonen2014). For some women postnatal depression reflects a chronic or recurrent condition, and a previous episode of depression during or before pregnancy is the most common risk factor for postnatal depression (Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Waldie, D’Souza, Peterson and Morton2017). Further, in the New Zealand context, antenatal and postnatal depression have also been shown to have distinct predictors (Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Waldie, D’Souza, Peterson and Morton2017; Waldie et al., Reference Waldie, Peterson, D’Souza, Underwood, Pryor, Carr, Grant and Morton2015). Approximately 17% of women experience antenatal depression symptoms, 13% postnatal depression, and 7% both antenatal and postnatal depression (Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Waldie, D’Souza, Peterson and Morton2016). Many of these women may not receive formal diagnoses or intervention. Given the varying presentation, maternal depressive symptoms (MDS) is an umbrella term used to describe elevated depressive symptoms experienced by women in the perinatal period (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019). For many women, depressive symptoms may begin to improve following infancy (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fearon, Cooper, Milgrom and Gemmill2015). The same period of the life course is known to be a particularly vulnerable time for establishing later child outcomes, and MDS has been considered an important potential influence during this critical and sensitive period (Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Hay, Pawlby, Schmücker, Allen and Kumar1995).

MDS and child language: potential mediating mechanisms

MDS has been associated with poorer child social, emotional, and behavioral development (Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Rouse, Connell, Broth, Hall and Heyward2011; Grace et al., Reference Grace, Evindar and Stewart2003; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kaaya, Chai, McCoy, Surkan, Black and Smith-Fawzi2017; Wachs et al., Reference Wachs, Black and Engle2009). Language ability represents one important aspect of children’s cognitive development that may have additional significance for developmental competence across other domains. In a recent narrative review, Salmon et al. (Reference Salmon, O’Kearney, Reese and Fortune2016) highlighted longitudinal associations of poorer child language ability with subsequent emotional, behavioral, and self-regulation difficulties, by high-quality studies controlling for multiple covariates. Interestingly, a recent meta-analysis, combining data from over 30,000 children, identified children’s receptive language as a stronger predictor of later behavior problems than expressive language (Chow et al., Reference Chow, Ekholm and Coleman2018). The authors suggest that language comprehension may be more important because children with difficulties in this area may withdraw from or avoid interactions with others that are experienced as too complex, thus limiting opportunities for social learning about emotions and how to regulate them. Recent reviews have identified associations between MDS and child cognitive development (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kaaya, Chai, McCoy, Surkan, Black and Smith-Fawzi2017), and more specifically child language (Slomian et al., Reference Slomian, Honvo, Emonts, Reginster and Bruyere2019). Many of these studies have been limited by use of a general cognitive index rather than a specific language measure and control of potential confounds, such as maternal education, that might underlie both maternal depression and child cognitive or language development (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kaaya, Chai, McCoy, Surkan, Black and Smith-Fawzi2017).

An understanding of the mechanisms that underlie this relationship between MDS and child outcomes is critical for researchers and clinicians working with high-risk families. Goodman and Gotlib’s (Reference Goodman and Gotlib1999) seminal model emphasizes multiple mechanisms through which MDS might impact child socioemotional, cognitive, or behavioral vulnerabilities, which ultimately explain the intergenerational transmission of mental health difficulties. Evidence has accumulated over the past two decades for each of the four proposed interacting mechanisms predicting child outcomes: (1) common genetics and epigenetic gene-environment interactions (van der Waerden et al., Reference van der Waerden, Bernard, De Agostini, Saurel‐Cubizolles, Peyre, Heude and Melchior2017); (2) neuroregulatory mechanisms (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Halligan, Goodyer and Herbert2010); (3) environmental stress (e.g., poverty); and (4) caregivers’ maladaptive cognitions, behaviors and affect. The third and fourth mechanisms encompass specific and modifiable environmental mechanisms which can directly inform prevention and intervention programs (Ahun & Côté, Reference Ahun and Côté2019).

What specific mechanisms might link early MDS and child language development? In line with attachment theory (Bowlby, Reference Bowlby1982), mutual social engagement is the foundation through which language and cognition develop across infancy and the preschool years. Ideally, mother-infant synchrony becomes increasingly sophisticated, moving from shared eye gaze and “motherese” to complex scaffolding of infant attention within which symbolic representation and early vocabulary are learned (Feldman, Reference Feldman2007). MDS is associated with increased negative (i.e., sadness, anger, distress, lability) and reduced positive affect which may reduce these interaction opportunities (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). This poses a concurrent and longer-term risk via cascading relational and socioemotional mechanisms for poorer child cognitive and language development (Easterbrooks et al., Reference Easterbrooks, Bureau and Lyons-Ruth2012; Feldman & Eidelman, Reference Feldman and Eidelman2009; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Bachorowski, Smoski and Hudenko2002; Maughan et al., Reference Maughan, Cicchetti, Toth and Rogosch2007).

Ahun and Côté (Reference Ahun and Côté2019) reviewed seven studies that specifically tested mediators in the relationship between MDS and child cognitive development. Overall, these studies provided preliminary evidence that MDS may relate to child language through mother-child interactions. For example, Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) found no direct association between MDS and later child language ability but did find support for an indirect negative link between MDS and language through positive caregiving (defined as maternal responsivity and opportunities for learning). This indirect negative relationship was stronger for mothers experiencing socioeconomic adversity. Milgrom et al. (Reference Milgrom, Westley and Gemmill2004) did not find support for maternal responsivity mediating MDS and cognition/language, although they used Baron and Kenny’s (Reference Baron and Kenny1986) causal steps approach which has been superseded by more contemporary tests of indirect effects (Hayes, Reference Hayes2009). This review also identified possible differences across sociocultural contexts: while Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Hwang, Wang, Chen, Lai and Chien2013) found that a stimulating home environment (defined as the quality and frequency of activities) mediated an association between MDS and children’s cognitive and language development among immigrant families, Piteo et al. (Reference Piteo, Yelland and Makrides2012) found no evidence of mediation with a Western US sample. Ahun and Cote highlighted that the research is limited by both the conflation of language and cognitive outcomes as well as the small number of longitudinal samples. In addition, there is some suggestion that an environmental mediating pathway may be especially important for families experiencing socioeconomic adversity, but further research is needed with large, diverse samples. Perhaps most importantly, although the extant research has largely used independent measures of child cognitive or language skill, there is a reliance on maternal report of both MDS and mother-child interactions.

Depression is associated with a pervasive negative interpretation bias (LeMoult & Gotlib, Reference LeMoult and Gotlib2019) that may result in more negatively biased self-report of parenting, irrespective of actual parenting interactions (van Doorn et al., Reference Van Doorn, Kuijpers, Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Bodden, Jansen and Granic2016). For example, Herbers et al. (Reference Herbers, Garcia and Obradović2017) found a greater discrepancy between self-reported and observed parenting behaviors for parents experiencing higher distress and lower SES. This effect was especially pronounced for negative, as opposed to positive, parenting behaviors. Stein et al.’s (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) positive caregiving construct was derived from both observations (of maternal responsivity) and self-report (of opportunities for learning), so it is difficult to parse out whether observed or self-reported parenting, or both, explains this relationship. We know of no studies to date that have specifically examined pathways of MSD to child language through both observed and self-reported parenting interaction, measured as distinct constructs. If an indirect effect can be demonstrated through observed parenting, this would reduce concerns about shared measurement bias and strengthen conclusions about this potential pathway.

A further limitation with the existing measurement of mediating pathways is that parenting as a mediator has been conceptualized in varied ways. This may have particular relevance for the specific child outcome measured. When considering child language outcomes, it is likely that aspects of the verbal or linguistic home environment will be particularly important to measure. A wealth of evidence indicates that language is socialized through interactions with more advanced conversational partners, predominantly parents (Garrett, Reference Garrett2020). Shared book-reading, parent-child conversations about past events (known as reminiscing), and child exposure to adult vocabulary are all examples of children’s early language environment. They may have differential impacts on children’s language development. For example, Zimmerman et al. (Reference Zimmerman, Gilkerson, Richards, Christakis, Xu, Gray and Yapanel2009) found that while exposure to adult language and TV viewing were associated, only longer adult-child conversations (measured by in-home recording software) were uniquely predictive of children’s independent language 18 months later. In a review of the literature, Reese et al. (Reference Reese, Sparks and Leyva2010) found that parent-training in dyadic book-reading, conversations. and writing were all associated with improved child language and literacy outcomes, beyond school-based interventions. Overall, these findings suggest that parent-child verbal interactions, as compared with more passive language exposure, may be especially important for language development. The MDS and child outcome literature, however, has not yet captured this potentially salient aspect of parenting.

Potential moderators of an association between MDS and child language

As noted above, the mechanisms by which MDS is associated with child language may differ based on the socioeconomic status of the populations studied. It may be that MDS is associated with poorer child language through parenting only or primarily under conditions of socioeconomic deprivation (Hay et al., Reference Hay, Pawlby, Waters and Sharp2008; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008). Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) found that associations between maternal postnatal depression and impaired caregiving (based on measures of responsivity, warmth, and stimulation) were strongest for less economically advantaged families. Ali et al. (Reference Ali, Mahmud, Khan and Ali2013) also found an interaction between maternal depression and income among Pakistani families; with children of mothers experiencing depression as well as low family income at five times greater risk of delayed language.

Differential effects may also be found based on child gender. Boys may be more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of MDS (Kurstjens & Wolke, Reference Kurstjens and Wolke2001; Milgrom et al., Reference Milgrom, Westley and Gemmill2004; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fiori-Cowley, Hooper and Cooper1996; Sharp et al., Reference Sharp, Hay, Pawlby, Schmücker, Allen and Kumar1995), even up to the age of 16 years (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Arteche, Fearon, Halligan, Goodyer and Cooper2011); however, this effect is not consistently observed (Cornish et al., Reference Cornish, McMahon, Ungerer, Barnett, Kowalenko and Tennant2005), and tends to be primarily found for behavioral and regulatory outcomes (Weinberg et al., Reference Weinberg, Olson, Beeghly and Tronick2006). Interestingly, there is also extensive interest and debate about gender differences in language development. Girls have traditionally been viewed as having superior language ability, although more recent meta-analytic evidence suggests any differences are not as pronounced as previously thought, and may be dependent on specific developmental stages and brain maturation (Etchell et al., Reference Etchell, Adhikari, Weinberg, Choo, Garnett, Chow and Chang2018). Gender differences in language may also reflect specific sociocultural contexts. For example, research in New Zealand tends to show a smaller language advantage for girls, compared with that on populations in the United States (US) samples (Reese & Read, Reference Reese and Read2000; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Keegan, McNaughton, Kingi, Atatoa Carr, Schmidt, Mohal, Grant and Morton2018). Understanding whether socioeconomic status and/or child gender moderate any associations of MDS with child language is important for appropriately and effectively targeting prevention and intervention resources (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008).

The current study

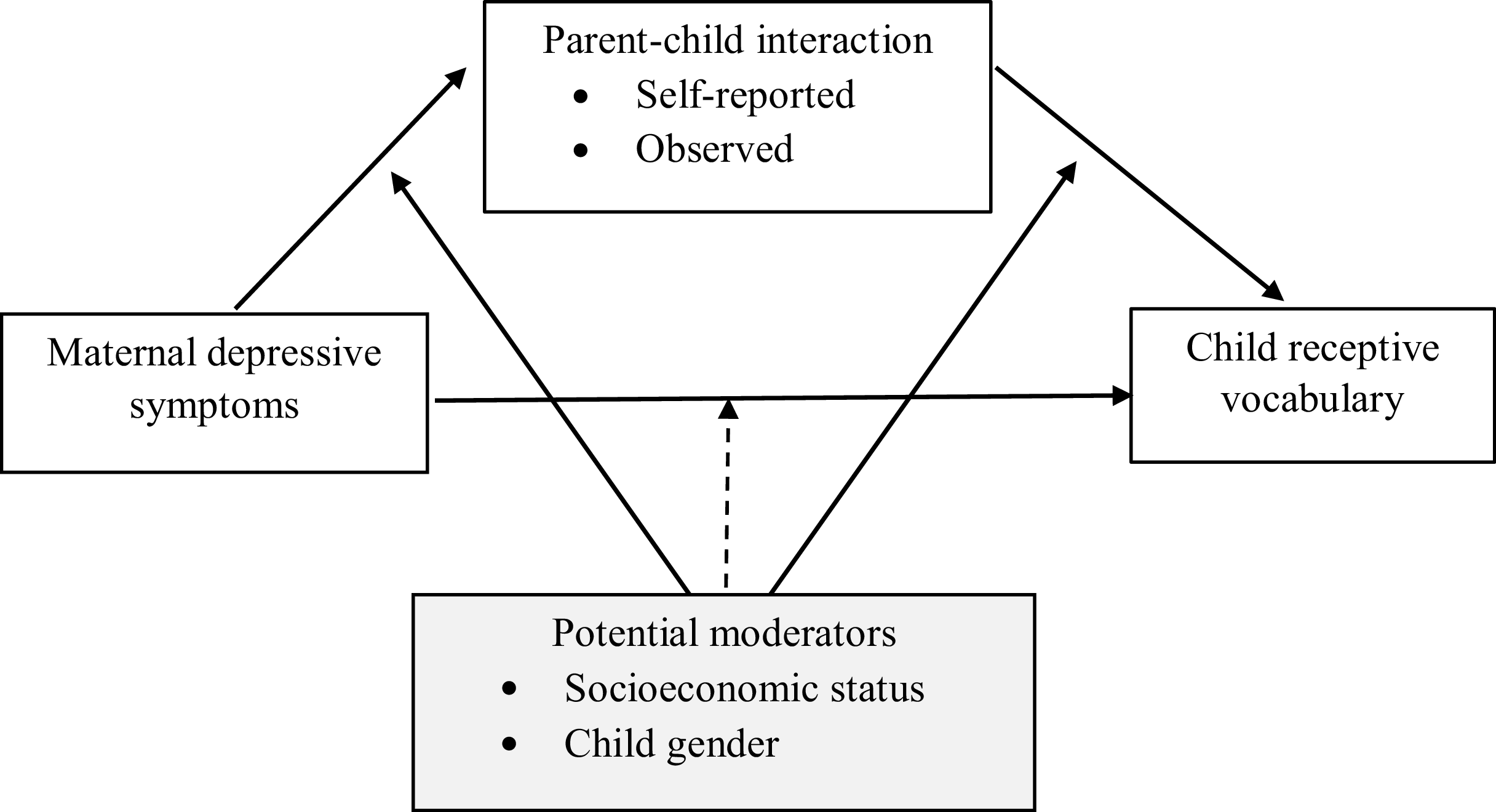

The current study utilized infancy and preschool data from a large, diverse, pre-birth longitudinal study: Growing Up in New Zealand. MDS was collected during infancy (9 months) and an independent measure of child receptive vocabulary was collected when children were aged 4 ½ years. Unique to large cohort studies, Growing Up includes both self-reported and observed parent-child verbal interactions at multiple time points. This allowed us to address limitations with the existing literature regarding how MDS relates to children’s language skills through the specific mediating pathways of both self-reported and observed mother-child verbal interactions during the preschool years. Importantly, the diversity of the sample also allowed adequate power to test for moderation by SES and child gender. Figure 1 demonstrates the potential relationships explored in the current study. The specific research questions and hypotheses were:

Figure 1. Potential mediation and moderated mediation relationships between MDS, parent-child interaction and child language.

-

1. Do both self-reported and observed parent-child verbal interactions during the toddler and preschool years mediate an association between postnatal MDS and child-receptive vocabulary prior to starting school? Based on theoretical models and the few existing studies using observations of parent behavior, it is predicted that both self-reported and observed verbal interactions will act as mediators.

-

2. Are these associations moderated by socioeconomic status and/or child gender? Existing literature provides some suggestion that an association between MDS and parenting is moderated by SES, although Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) could not examine whether a mediating relationship predicting child language was also moderated by SES as there was no direct association between MDS and language. Similarly, there is evidence that the impact of MDS is greater on boys, but moderated mediation from MDS to parenting to language has yet to be tested. Potential relationships are depicted in Figure 1.

New Zealand represents an important sociocultural context for this research. The majority of research on mental health during infancy has been conducted with US or European samples (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Bornstein, Marlow and Swartz2014). New Zealand has a culturally diverse population, with approximately 17% of the population identifying as Māori (the Indigenous people of Aotearoa New Zealand). New Zealand also has heterogeneous Pacific (8%) and Asian (15%) populations (Statistics, Reference Statistics2018). The intergenerational impacts of colonization continue to impact within New Zealand in the form of systemic racism and other socio-ecological inequities, contributing to the higher rates of perinatal mental health difficulties experienced by Māori women in New Zealand (Signal et al., Reference Signal, Paine, Sweeney, Muller, Priston, Lee, Gander and Huthwaite2017). Although we examined socioeconomic status not culture as a moderator, Māori, and ethnic minorities are disproportionately impacted by poverty in New Zealand, again through intergenerational impacts of colonization and systemic racism (Hobbs et al., Reference Hobbs, Ahuriri-Driscoll, Marek, Campbell, Tomintz and Kingham2019). In this way, socioeconomic status represents an important ecological risk factor with implications for maternal mental health and child development (Feldman & Masalha, Reference Feldman and Masalha2007).

Method

Participants

Growing Up in New Zealand was designed as a longitudinal study to follow children from before birth to 21 years. The overarching goals of the study were to contribute to health and wellbeing of New Zealand’s contemporary and diverse population. All pregnant mothers living in three adjoining health board regions in the central North Island of the country (Auckland, Counties Manukau, and Waikato) with an estimated due date between 25 April 2009 and 25 March 2010 were eligible to be part of the Growing Up in New Zealand study (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Grant, Carr, Robinson, Kinloch, Fleming, Kingi, Perese and Liang2014), and 6,822 pregnant women consented. The resulting cohort of 6,583 infants represented 11% of the national live births over the study recruitment period (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Atatoa Carr, Grant, Robinson, Bandara, Bird and Wall2013), and have been found to be broadly representative of the New Zealand population (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Ramke, Kinloch, Grant, Carr, Leeson, Lee and Robinson2015). Child sex and singleton/multiple did not differ from national births although Growing Up cohort children were less likely to be low birth weight or preterm. In line with the study design and recruitment approach, the cohort was more ethnically diverse than national births (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Ramke, Kinloch, Grant, Carr, Leeson, Lee and Robinson2015). Substantive data collection waves (DCWs) with the Growing Up cohort have occurred to date in pregnancy, and when the children were aged 9 months, 2 years, 4 ½ years, and 8 years. The current sample (n = 4,432) represents those who had completed both the child language components measured at 4 ½ years and the observed parent-child verbal interactions (at both 2 and 4 ½ years).

Procedure

Families were visited in the home when children were aged 9 months, 2 years, and 4 ½ years. A trained interviewer administered the Computer Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI) face-to-face with mothers. At age 2 and 4 ½ years, interviewers also invited families to take part in the parent-child interaction. At age of 4 ½ years, interviewers administered the language measure to children via CAPI.

Measures

Sociodemographic variables

Mothers reported on self-prioritized ethnicity during pregnancy and results were grouped into European, Māori (Indigenous peoples of New Zealand), Pacific Peoples, Asian and MELAA (Middle Eastern, Latin American and African), and Other (Statistics New Zealand, 2005). For the purposes of this study, and given sample size considerations, the ethnic groups of “MELAA” and “Other” have been collapsed into one “Other” category. Mothers also reported their highest education which was grouped into no secondary school, secondary school, a trade or diploma, Bachelor’s degree, or higher degree. Mothers also self-reported their age, and a proxy of child gender was attained by linking with birth hospital records which recorded sex assigned at birth. Based on self-reported primary home address at age 4 ½ years, participant area-level socioeconomic deprivation was calculated using NZDep2013 (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Salmond and Crampton2014). For NZDep2013, the census data for income, home ownership, educational qualifications, family structure, housing, and resource access were combined across small geographical areas (meshblocks of around 100 people), thus providing an area-based index of socioeconomic status (SES). Low scores of 1 reflect the lowest 10% of deprivation (comparable to high SES) and high scores of 10 reflect the highest 10% of deprivation (comparable to low SES). NZDep2013 can be further grouped into low deprivation (1–3), medium deprivation (4–7) and high deprivation (8–10). Criterion validity of the NZDep has been established against multiple health and health behavior indicators (NZDep1991 and NZDep1996; Crampton et al., Reference Crampton, Salmond, Sutton, Crampton and Howden-Chapman1997; Salmond et al., Reference Salmond, Crampton and Sutton1998) and against national census information (NZDep2006 and NZDep2013; Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Salmond and Crampton2014).

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

The EPDS (Cox et al., Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky1987) is a well-validated measure of depression symptoms experienced during pregnancy and in the postnatal periods, with validation demonstrated across a diversity of cultures (Areias et al., Reference Areias, Kumar, Barros and Figueiredo1996; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Heron, Francomb, Oke and Golding2001; Su et al., Reference Su, Chiu, Huang, Ho, Lee, Wu, Lin, Liau, Liao, Chiu and Pariante2007). The EPDS contains 10 items specifically designed to identify symptoms of depression not confounded by the physical symptoms of the perinatal period (e.g., sleep difficulty). Mothers’ self-reported depression symptoms using the EPDS at the 9-month DCW are used in the current study. Given the focus of the current study is on maternal depressive symptoms, rather than “possible” or “probable” depression, total EPDS scores were analyzed as a continuous variable (Matthey et al., Reference Matthey, Henshaw, Elliott and Barnett2006).

Abridged Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Third Edition (a-PPVT)

The PPVT-III (Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn1997) is a widely used and well-validated measure of children’s receptive vocabulary. For each item, children are presented with four pictures and asked to point to the picture that corresponds to a spoken word (e.g., “ball”). An abridged version of the PPVT-III (a-PPVT) was developed by the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC). Australian children (n = 215) aged between 41 and 66 months were administered the PPVT-III and Rasch modeling identified a reduced set of 40 items (Australian Council for Educational Research, 2000; Sanson et al., Reference Sanson, Misson, Hawkins and Berthelsen2010). This abridged version has been widely utilized in LSAC analyses (Brinkman et al., Reference Brinkman, Silburn, Lawrence, Goldfeld, Sayers and Oberklaid2007; McLeod & Harrison, Reference McLeod and Harrison2009; Quach et al., Reference Quach, Hiscock, Canterford and Wake2009; Spilt et al., Reference Spilt, Koomen and Harrison2015) and was administered within Growing Up in New Zealand. Participant scores were converted to a z score (Galvin et al., Reference Galvin, Davis, Neumann, Underwood, Peterson, Morton and Waldie2020) which was used in all subsequent analyses.

Mother-child interaction tasks

The administration and accurate coding of parent-child verbal interactions are challenging and resource-heavy within large cohort studies. Interviewers were therefore trained and established reliability to code before going to field. A time-sampling approach was used, where interviewers coded for one behavior or verbalization at a time within successive 30-s time periods. This combination of time sampling and pre-established reliability has been utilized to establish reliability in other very large sample research, for example in education settings (Coffman et al., Reference Coffman, Ornstein, McCall and Curran2008). The methodology and coder training of parent-child interaction tasks within Growing Up in New Zealand are described in more detail by Reese et al. (Reference Reese, Bird, Taumoepea, Schmidt, Mohal, Grant, Atatoa Carr and Morton2016). All interviewers were required to achieve >80% reliability on sets of prerecorded dyadic interactions before each DCW. Reliability checks were conducted mid-way through each DCW to prevent coding drift. Observed mother-child interactions from both the 2 and 4 ½ year DCWs were utilized in the current study.

2-year mother-child interaction task: Mothers were asked to describe five pictures to their toddlers. Each picture was chosen to elicit a specific component of parent-child interaction, and coders were trained using a time-sampling approach to code the first 30 s of each picture description for maternal warmth, maternal open-ended questions, maternal desire or emotion words, children’s emotional expression, and maternal language linking pictures to children’s own life (Reese et al., Reference Reese, Bird, Taumoepea, Schmidt, Mohal, Grant, Atatoa Carr and Morton2016). Given the current analyses are focused on the home language environment, only the verbal constructs are considered here. A total 2-year maternal verbalization score, ranging from 0 to 5, was calculated from maternal open-ended questions (0 = no questions, 1 = one question, 2 = two or more questions), maternal desire or emotion words (0 = no desire or emotion words, 1 = one desire or emotion word, 2 = two or more desire or emotion words) and maternal linking scores (0 = no link made to child’s own life, 1 = a link is made to child’s block play or any other relevant aspect of child’s life).

4 ½ year mother-child interaction task: Mother-child dyads were given a template and asked to work together to write a birthday party invitation (Aram et al., Reference Aram, Meidan and Deitcher2016; Aram, Reference Aram2002). Again, a time-sampling approach was used, with the first 30 s of the task coding for maternal open-ended questions (0 = no questions, 1 = one question; 2 = two or more questions); the second 30 s for maternal print talk (0 = no print talk, 1 = one instance of print talk, 2 = two or more instances of print talk); and the third 30 s for maternal praise and encouragement (0 = no praise or encouragement, 1 = one instance of praise or encouragement; 2 = two or more instances of praise or encouragement). These were summed to give a total 4 ½ year maternal verbalization score, ranging from 0 to 6.

Self-reported mother-child verbal interactions

In addition to observed interactions, parents were asked to report on how often they engaged in a range of different types of interactions with their infants and toddlers. The frequency response scale ranged from 1 (seldom or never) to 5 (several times a day) for each item. At each data collection wave, the following types of verbal interactions were asked about:

2 years: read books with child; tell stories to child (not including books). These items were summed to give a total 2-year self-reported parent-child verbal interaction score ranging from 2 to 10 (α = 0.307).

4 ½ years: read books with child; tell stories to child (not including books); sing songs or play music with child; encourage child to print letters, words, or numbers; encourage child to read words; encourage child to count; and encourage child to recognize numbers. These items were summed to give a total 4 ½-year self-reported parent-child verbal interaction score ranging from 7 to 35 (α = .940).

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted on SPSS Version 27.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated. Preliminary associations were tested using: Pearson’s correlations (continuous variables), Spearman’s rho correlations (ordinal variables), independent sample t-tests (child gender differences for continuous variables), and Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxin and Kruskal-Wallis tests (comparing means for categorical DV and ordinal IVs; MacFarland et al., Reference MacFarland, Yates, MacFarland and Yates2016).

Mediation and moderation hypotheses were tested using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018), controlling for sociodemographic covariates. PROCESS uses bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals to test the indirect effect. This is a contemporary approach that allows non-normality and asymmetry, and is robust, balancing power and validity concerns (Hayes & Preacher, Reference Hayes and Preacher2013; Hayes, Reference Hayes2009, Reference Hayes2013). Estimates were based on 5,000 bootstrap samples, using 95% confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2004, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008). Confidence intervals that do not cross zero are indicated as support for the indirect pathway. Two parallel mediation models were tested. Parallel mediation tests multiple different mediation pathways within the same model, while accounting for shared variance (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). The first parallel mediation model tested indirect pathways of MDS to child receptive vocabulary through observed verbal interaction scores: with one pathway through 2 year observed interaction and the parallel pathway through 4 year observed interaction. The second parallel mediation model tested indirect pathways of MDS to child receptive vocabulary through self-reported verbal interaction scores: with one pathway through 2 year self-reported interaction and the parallel pathway through 4 year self-reported interaction.

Conditional process analysis within PROCESS test for moderated mediation, to examine whether mediating pathways vary as a function of the moderator. The moderator can be tested at the first-stage (model 7) or second-stage (model 8), or both (model 59). The latter tests whether the mediating pathway as a whole is supported at different levels of the moderator, and was used in the current analyses (Hayes, Reference Hayes2017; Hayes & Rockwood, Reference Hayes and Rockwood2020).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics for potential covariates and main variables of interest are shown in Table 1. Missing data represented ≤5% for each of the variables and Little’s MCAR analysis were not significant, indicating data were missing at random (χ = 77.90, p = .06). Because of this, the decision was made not to impute or substitute data, resulting samples <4,432 for subsequent multivariable analyses due to listwise deletion with PROCESS. However, with low missingness and a large dataset, potential bias due to listwise deletion is considered minimal (Schafer, Reference Schafer1999). Inspection of histograms indicated that despite being ordinal scales, the four parent-child verbal interaction variables were all normally distributed, with skewness and kurtosis values ±1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables: means, SDs, frequencies and percentages

Pearson’s and Spearman’s rho correlations are shown in Table 2. Higher area-level socioeconomic deprivation was significantly correlated with higher EPDS scores, lower child receptive vocabulary, and all four parent-child verbal interaction scores. All parent-child verbal interaction scores had small significant positive correlations with child receptive vocabulary and small significant negative correlations with maternal EPDS scores. Gender differences were examined using independent sample t-tests and Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxin tests. Girls had higher a-PPVT scores (t = −3.54, p < .001), higher maternal self-reported verbal interaction at 4 ½ years (U = 2346003, p = .009), and higher observed verbal interaction scores at 4 ½ years (U = 2348538.5, p = 0.017). Maternal ethnicity patterns were examined using Kruskal-Wallis tests. European mothers had the highest 2-year self-reported (K = 210.20, p < .001) and 4 ½ year observed (K = 66.34, p < .001) verbal interactions, compared to all other ethnic groups. Asian mothers had the highest self-reported verbal interactions at 4 ½ years (K = 33.79, p < .001), and “Other” ethnicity (MELAA and Other ethnicity combined) mothers had the highest observed verbal interactions at 2 years (K = 32.12, p < .001). University-educated mothers had higher verbal interactions for 2 (K = 151.84, p < .001) and 4 ½ year (K = 30.37, p < .001) self-report and 2 (K = 9.66, p < .001) and 4 ½ year (K = 20.89, p < .001) observations, compared to mothers of all other educational levels.

Table 2. Pearson and Spearman’s rho correlations among variables

Note. EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; a-PPVT = abridged Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; SR PCVI = self-reported parent-child verbal interaction; Obs. PCVI = observed parent-child verbal interaction.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; ****p < .0001.

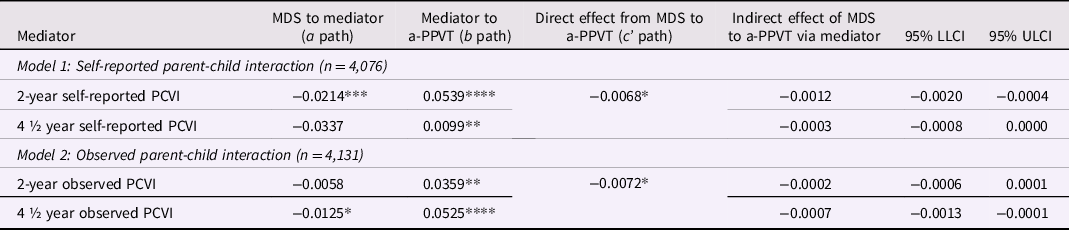

Mediation analyses

Indirect effects of MDS at 9 months on child language (a-PPVT) at 54 months through parent-child verbal interaction were tested (see Table 3). Two parallel mediation models were created: one for self-reported parent-child verbal interaction (with 2 year and 4 ½ years as the parallel pathways); and the other for observed parent-child verbal interaction (again with 2 year and 4 ½ year observations as the parallel pathways). In both models, the following dummy covariates were entered: maternal education (high school or less), languages spoken at home (monolingual versus two or more languages), child gender, and maternal ethnicity (European versus all other ethnic groups). There was a direct negative effect of MDS on child language in both self-reported and observed verbal interaction models. There was also support for an indirect effect of MDS on 4 ½ year child receptive vocabulary through self-reported verbal interaction at 2 years (z = −0.0013, 95% CIs −0.0028, −0.0007) but not 4 ½ years (z = −0.0003, 95% CIs −0.0008, 0.0000). There was also support for an indirect effect of MDS on 4 ½ year child receptive vocabulary through observed verbal interaction at 4 ½ years (z = −0.0007, 95% CIs −0.0014, −0.0001) but not 2 years (z = −0.0002, 95% CIs −0.0007, 0.0001). In both models, covariates remained significant unique predictors: mothers with a high school education only and living in more deprived areas had children with lower receptive vocabulary scores; European maternal ethnicity and speaking one language at home were associated with higher child receptive vocabulary.

Table 3. Indirect effect coefficients for the parallel mediation models of maternal depression on child language, mediated through self-reported and observed parent-child interaction

Note. MDS = maternal depressive symptoms; a-PPVT = abridged Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test; PCI = parent-child verbal interaction.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001; ****p < .0001.

Moderated mediation analyses

A series of moderated mediation analyses were then conducted to examine whether mediation pathways of MDS to child language through parent-child verbal interaction were moderated by either child gender or area deprivation. Area-level SES was dichotomized into high deprivation versus low-medium deprivation. In both models, dummy covariates were entered for maternal education (high school or less) and languages spoken at home (monolingual versus two or more languages). For the models testing child gender as the moderator, area deprivation was also entered as a covariate. For the models testing area deprivation as the moderator, child gender was also entered as a covariate. There was no support for a difference in conditional indirect effects due to child gender for mediation through self-reported verbal interaction at age 2 years (95% CIs −0.0026, 0.0009), self-reported verbal interaction at age 4 ½ years (95% CIs −0.0016, 0.0010), observed verbal interaction at age 2 years (95% CIs −0.0010, 0.0006), or observed verbal interaction at age 4 ½ years (95% CIs −0.0006, 0.0019).

There was no support for a conditional indirect effect due to area-level SES for mediation through self-reported verbal interaction at age 2 years (n = 4077; 95% CIs −0.0021, 0.0018), self-reported verbal interaction at age 4 ½ years (n = 4129; 95% CIs −0.0025, 0.0006), or observed verbal interaction at age 2 years (n = 4131; 95% CIs −0.0015, 0.0006). There was however support for a conditional indirect effect due to area-level SES for mediation through observed verbal interaction at age 4 ½ years (n = 4131; 95% CIs −0.0038, −0.0003). While we found an indirect effect of MDS on child receptive vocabulary through observed verbal interaction at 4 ½ years was not supported at low-medium deprivation (z = 0.0000, 95% CIs −0.0008, 0.0008), there was support for the indirect effect at high levels of socioeconomic deprivation (z = −0.0019, 95% CIs −0.0037, −0.0006). For specific pathways within the model, the direct effect of MDS on child receptive vocabulary was not conditional on area-level SES (ΔR 2 = 0.0000, p = 0.96), nor was the direct effect of observed 4 ½ year verbal interaction on child language conditional on area-level SES (ΔR 2 = 0.0000, p = 0.86). The simple moderation effect of area deprivation in the relationship between MDS and observed verbal interaction at 4 ½ years is shown in Figure 2. There was a significant relationship at high deprivation (effect = −.0373, p = 0.0002, 95% CIs −0.0570, −0.0175), but not low-medium deprivation (effect = −.0001, p = 0.98, 95% CIs −0.0142, 0.0139). In summary, there was no support for moderated mediation by gender on the relationship of MDS to child language through parent-child verbal interaction. There was evidence for moderated mediation of MDS to child language through observed verbal interaction at 4 ½ years, with mediation supported for those living in high-deprivation areas.

Figure 2. Area-level socioeconomic status as a moderator of the relationship between maternal depression symptoms (9 months) and observed parent-child interaction (4 ½ years).

Discussion

The current study examined a mediation pathway of MDS during infancy to later child language through parent-child verbal interaction, using a large and diverse longitudinal cohort in New Zealand. Importantly, the data included: (1) an independent measure of child language (receptive vocabulary) as the outcome; (2) specifically assessed verbal aspects of mother-child interaction; and (3) included both self-reported and observed mother-child interactions. Across the whole sample, results indicated support for mediation pathways between MDS (as measured by the EPDS) and child-receptive vocabulary through self-reported mother-child interaction at age 2 years, and through observed mother-child interaction at age 4 ½ years. In addition, conditional process analyses indicated that the mediation pathway through observed verbal interaction at 4 ½ years was moderated by area-level SES, with this indirect effect only supported for children living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation.

Existing literature has demonstrated an association of MDS with children’s later cognitive outcomes, which sometimes also include measures of language. In line with past research (Cornish et al., Reference Cornish, McMahon, Ungerer, Barnett, Kowalenko and Tennant2005; Hay & Kumar, Reference Hay and Kumar1995; Husain et al., Reference Husain, Cruickshank, Tomenson, Khan and Rahman2012; Koutra et al., Reference Koutra, Chatzi, Bagkeris, Vassilaki, Bitsios and Kogevinas2013; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008), the current findings demonstrate a small but direct association of MDS with later child language. Interestingly, the majority of existing studies showed no association between MDS and language assessed in the toddler years, using scales where both expressive and receptive language were considered together. In contrast, our measure was specific to receptive language and was measured in the late preschool years and did show a relationship with MDS. Ahun et al. (Reference Ahun, Geoffroy, Herba, Brendgen, Séguin, Sutter-Dallay, Boivin, Trembla and Côté2017) also measured receptive language and showed an association of MDS chronicity with language at 5, 6, and 10 years. Development builds upon itself (Sroufe, Reference Sroufe2013), and it may be that early elevated MDS reflects the beginning of a cascade of poorer quality interactions that over time contribute to progressive detrimental impacts on children’s later receptive language abilities. But why might MDS be related to lower child receptive, rather than expressive, language? Different socialization mechanisms are likely to be involved in the development of receptive and expressive language. For example, in a recent systematic review, Scheiber et al. (Reference Scheiber, Ryckman and Demir-Lira2022) found that MDS was associated with reduced overall amount, but not complexity, of child-directed speech. This may in turn have differential impacts on receptive vocabulary versus expressive language production. Further, receptive language difficulties are less likely to be noticed by parents and teachers (Toppelberg & Shapiro, Reference Toppelberg and Shapiro2000) and this may be exacerbated by poorer caregiver responsivity and greater environmental stressors associated with MDS.

The current study examined one such specific pathway: maternal verbal interactions during the preschool years. Our findings support the handful of existing empirical studies demonstrating that parenting mediates an association between MDS and child language (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hwang, Wang, Chen, Lai and Chien2013; Stein et al., Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008). We extended this research by adopting a more specific conceptualization of parenting reflecting the home language environment and considering both self-reported and observed parent verbal interactions. These findings are in line with theoretical perspectives (Goodman & Gotlib, Reference Goodman and Gotlib1999) that the increased negative and reduced positive affect of MDS impact poorer quality parent-child interactions. Although not measured here, the relationship between MDS during infancy and later poorer quality verbal interactions may be a result of early relational or attachment difficulties “carried forward” into the toddler and preschool years. As noted by van IJzendoorn et al. (Reference van IJzendoorn, Dijkstra and Bus1995), securely attached children tend to display higher language skills than insecurely attached children. This may reflect early synchronous patterns of interacting (Feldman, Reference Feldman2007), enabling parents to become more competent and sensitive “teachers” and children to develop into more responsive “students” (Van IJzendoorn et al., Reference van IJzendoorn, Dijkstra and Bus1995, p. 115). This may also reflect epistemic trust. If children trust a caregiver, they can also trust, and therefore learn, information conveyed within this relationship (Fonagy & Bateman, Reference Fonagy and Bateman2016). Further research examining longitudinal associations and an independent measure of attachment will help to elucidate these relational mechanisms.

Interestingly, mediation was supported for self-reported parent-child verbal interactions at age 2 (but not 4 ½) years; and for observed parent-child verbal interactions at 4 ½ (but not 2) years. This difference might be explained by differences in the way verbal interactions were conceptualized at the two time points in our study. At age 2, the self-report measures reflected story-telling and book-reading (and the observed interaction task mirrored this), whereas age 4 ½ included story-telling and book-reading, as well as more formal literacy focused aspects of interactions (e.g., teaching print concepts). Again, the observed parent-child interaction of completing a written birthday party invitation mirrored this more structured literacy focus. It may be that any social desirability bias is enhanced for activities that parents perceive as formal “literacy teaching,” and therefore observations of literacy-related interactions may reflect a more valid indicator than self-report of literacy-related interactions. Regardless, the separate measurement of self-report and observed verbal interaction, and evidence for both as mediators (albeit at different time points), provides support for parent verbal behavior as a pathway through which early MDS might impact later child language development.

Importantly, there was also evidence that the mediating pathway from MDS to language through observed parent-child verbal interaction was moderated by area-level socioeconomic deprivation. This pathway was supported for families living in areas of higher deprivation, but not for families living in low-medium deprivation areas. There was also a simple moderating effect for the relationship between MDS and observed parent-child interaction. For children growing up in high-deprivation areas, greater exposure to MDS during infancy was associated with poorer quality parent-child verbal interactions at 4 ½ years, but there was no association between MDS and parent-child interaction for children growing up in low-medium deprivation areas. These findings support those of Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) who also found that the relationship between MDS and parent-child interaction was stronger for low-SES families. This likely reflects the multiple and complex burdens experienced by parents with mental health difficulties also experiencing socioeconomic hardship, and the impact of socioeconomic disadvantage and its associated challenges on parental mental health. Our findings therefore support the priority of improving the socioeconomic status of families with young children and concur with Stein et al.’s (Reference Stein, Malmberg, Sylva, Barnes and Leach2008) call for MDS interventions to be targeted towards families experiencing socioeconomic deprivation. It may be that prioritizing postnatal intervention resources towards low-SES families will see greater benefits for parent-child interactions and subsequent child language development. Although we considered maternal ethnicity as a covariate rather than a moderating variable, these findings may have implications for ethnic minority and Indigenous families. In New Zealand and internationally the impacts of colonization, historical trauma, and systemic racism have led to inequities in maternal mental health, parenting, and child development (Smallwood et al., Reference Smallwood, Woods, Power and Usher2021). Maternal education (high school only) also remained a significant predictor of child language across models. These findings highlight a need to address the complex ecological stressors experienced by families in order to build parenting capacity (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Dáu, Goldblum, Alfano and Smith2017).

This is particularly important because child language is increasingly seen as a transdiagnostic factor underpinning children’s own mental health difficulties (Salmon et al., Reference Salmon, O’Kearney, Reese and Fortune2016). It may be that parent-verbal interactions with child language development represent one pathway through which mental health difficulties are transmitted from parent to child (Goodman, Reference Goodman2020). Understanding such specific mechanisms has important implications for targeted prevention and intervention programs. There is robust evidence that both MDS and parent-child verbal interactions (Corsano & Guidotti, Reference Corsano and Guidotti2019; Reese et al., Reference Reese, Sparks and Leyva2010) are modifiable. In particular, community-based programs have been developed to promote parent-toddler book-reading and language interactions among low-income families (e.g., “Reach Out and Read,” Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Hiebert, Scott and Wilkinson1985; “Little Talks,” Manz et al., Reference Manz, Rigdard, Faison, Whitenack, Ventresco, Carr, Sole, Cai, Sonnenschein and Sawyer2018). For example, Little Talks was designed to target both the home language and learning environment and parental depression, and there is some evidence that Reach Out and Read prevents worsening of depression symptoms among adolescent mothers (Kumar et al., Reference Kumar, Cowan, Edrmann, Kaufman and Hick2016).

Moreover, children growing up in socioeconomic adversity are more likely to begin school with fewer early learning foundational skills (Bird et al., Reference Bird, Reese, Waldie, Peterson, Atatoa-Carr, Morton and Grantin press; Magnuson et al., Reference Magnuson, Meyers, Ruhm and Waldfogel2004), which compound across the school years and predict later academic achievement deficits (Evans & Rosenbaum, Reference Evans and Rosenbaum2008; Howse et al., Reference Howse, Lange, Farran and Boyles2003; McClelland et al., Reference McClelland, Morrison and Holmes2000; Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, Reference Sohr-Preston and Scaramella2006). Our findings suggest that these children are also impacted to a greater degree by exposure to MDS. This is especially concerning given that mothers living in poverty are more likely to experience MDS. In addition, high levels of stress related to food insecurity, intergenerational trauma, neighborhood safety, finances, transport, housing, and employment (instability and/or inflexibility) can impact a parent’s capacity to spend time with their child, or parent in the way they want to (Lange et al., Reference Lange, Dáu, Goldblum, Alfano and Smith2017). If parenting intervention resources are indeed targeted towards families experiencing greater socioeconomic adversity, it may also be important to directly target financial stress. For example, the New Hope Project provided 1 year of income supplement, and subsidized health insurance and child care to Wisconsin US families living in poverty. Positive benefits were found primarily for sons, with a reduction in child behavior problems and improved academic achievement (Huston et al., Reference Huston, Duncan, McLoyd, Crosby, Ripke, Weisner and Eldred2005), as well as improved parenting behaviors after 5 years (Epps & Huston, Reference Epps and Huston2007). The Smart Beginnings program provides a population-level approach, targeting the modifiable early parent-child relationship as a mechanism through which systemic racism and poverty contribute to school readiness inequities. Smart Beginnings provide a tiered approach, targeting prevention and then intervention based on family risk, with particular benefits found for the latter with parents experiencing mental health problems. Importantly, Smart Beginnings was explicitly designed to reduce barriers for low-income parents to engage in parenting support (e.g., child care, travel, and work hours) (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Mendelsohn and Morris2021). At the policy level, the New Zealand Child Poverty Reduction Act recognizes the long-term impacts of child poverty and has established specific targets, measures, and reporting systems with the goal of reducing child poverty and associated inequities. These intervention programs together with our findings point to the importance of addressing family financial stress alongside parent-child relational interventions.

The timing of interventions may also be important to consider. As highlighted by Sroufe (Reference Sroufe2013, p. 1218), “change is possible at every point in development…. the longer a pathway is followed, the more difficult change becomes.” There is evidence that treating early maternal depression can improve later child development outcomes (Letourneau et al., Reference Letourneau, Dennis, Cosic and Linder2017) and that improvements in parenting behaviors following such intervention may explain improved child outcomes (Goodman & Garber, Reference Goodman and Garber2017). However, a recent review of intervention studies that targeted postnatal depression and parent interactions during infancy found no overall evidence of improvements in parenting or child development outcomes (Rayce et al., Reference Rayce, Rasmussen, Skovgaard and Pontoppidan2020). A multi-staged intervention approach may be needed. For example, intervention might first focus on MDS and establishing a positive parent-infant relationship during infancy, in addition to later targeting parent-preschooler interactions among at-risk families.

There was no evidence of moderation by gender: neither in the association between MDS and language nor in the indirect pathways tested through parent-child verbal interactions. A recent systematic review of studies examining gender, parent socialization. and child outcomes highlighted that while gender differences were found, there was no evidence of an association between gendered parenting behaviors and child outcomes (Morawska, Reference Morawska2020). There is also some evidence that differences in parent language between daughters and sons may be decreasing over time (Aznar & Tenenbaum, Reference Aznar and Tenenbaum2020; Leaper et al., Reference Leaper, Anderson and Sanders1998). It may be that gendered parenting behaviors are declining over time, or that differences are more likely to be seen when considering parent behaviors such as emotional talk, behavior management, and play (Morawska, Reference Morawska2020). Certainly, any moderation of parenting associations by child gender may be dependent on the specific sociocultural context.

Strengths and limitations

Notable strengths of this study include the large and diverse sample, the longitudinal design, independent observations of parent-child interactions, a direct measure of child language, and mediation tested across multiple time points. Utilizing data from this large national cohort study also allowed for inclusion of potential covariates in the relationship between MDS and child language, such as maternal education (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Kaaya, Chai, McCoy, Surkan, Black and Smith-Fawzi2017) to be included in all models.

We examined language development in particular and identified mother verbalizations during interactions with their child as one mechanism. Growing Up did not have a measure of expressive language at age 4 ½ years, but it will be important for future research to consider parent-child mechanisms predicting this and other child cognitive outcomes. Other mechanisms may be important for other child development outcomes. For example, parent-child emotion regulation may be especially important for children’s socioemotional and behavioral outcomes; parenting interactions that support attention regulation may be especially important for children’s cognitive development (Madigan et al., Reference Madigan, Brumariu, Villani, Atkinson and Lyons-Ruth2016; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Fearon, Cooper, Milgrom and Gemmill2015). Potential covariates not considered here may also underlie associations. For example, challenging child temperament and/or child health or developmental issues may increase risk for MDS, poorer quality parenting interactions, and potentially poorer child outcomes. Other maternal mental health difficulties, beyond MDS, may also be important to consider. Judd et al. (Reference Judd, Newman and Komiti2018) have called for a shift in perinatal mental health research away from postnatal depression alone and towards “high-risk” caregiving including personality difficulties, trauma, and substance abuse.

It is also important to note that we tested pathways for mothers only. Although Growing Up has father reported depressive symptoms, we did not have independent observations of father-child interactions. Recent evidence highlights the importance of father-child verbal interactions (particularly during book-reading) for later child language skill among a US Head Start population (Fagan et al., Reference Fagan, Iglesias and Kaufman2016). Future research should examine unique contributions of multiple caregiver interactions in child language development.

The mediating pathway through self-reported verbal interactions at age 2 should be interpreted with caution, as this was based on a two-item scale with very low internal consistency. The two verbal items were collected as part of a set of questions tapping a range of parent-child interactions and were selected post hoc. Two-item scales are recognized as problematic (Eisinga et al., Reference Eisinga, te Grotenhuis and Pelzer2013) and further research is needed with a more comprehensive indicator of self-reported parent-child verbal interaction in the toddler years. There may also be psychometric limitations to the observed verbal interaction scales. The 2 and 4 ½ year scales had different ranges (due to the verbal linking construct at age 2 only being measured as present or absent rather than on a 3-point scale). Training interviewers to reliably code before going to field allowed us to observe parent-child interaction across the full sample; however, this coding method necessarily confines measurement to a few select behaviors. Recording and subsequent fine-grained coding of other aspects of the interactions may elucidate further mediating mechanisms. For example, it will be important to analyze parents’ use of pedagogical questions (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Bonawitz and Shafto2019), complexity of vocabulary and syntax structure, and contingent responding (Rowe, Reference Rowe2018). It also appears that the effects of MDS on parenting behavior may be more apparent in greater display of negative behaviors, rather than lesser positive behaviors (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). This suggests that our measurement of positive verbal behaviors may potentially underestimate the mediation pathway effect and that further research should consider negative verbal parenting behaviors as well (e.g., interrupting, negation, or disagreement). In addition, mediation should ideally be tested with the independent, mediating, and dependent variable at different points across time (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018). For models with parent verbal interactions from 4 ½ years, the relationship with language is cross-sectional, and maternal verbal interaction may in fact reflect their child’s current language skill.

Our measurement of MDS using the EPDS warrants further discussion. Because mothers are typically the primary carers during early infancy and infants are highly sensitive to stimulation, there is some suggestion that exposure to MDS during infancy may have a larger developmental impact. In contrast, Ahun et al. (Reference Ahun, Geoffroy, Herba, Brendgen, Séguin, Sutter-Dallay, Boivin, Trembla and Côté2017) found that chronic exposure to MDS throughout the preschool years, as opposed to the specific timing of exposure, explained differences in later child language. Interestingly, Brennan et al. (Reference Brennan, Hammen, Andersen, Bor, Najman and Williams2000) found that while the timing of moderate-severe MDS predicted the severity of children’s behavior problems, it was only the level of MDS – not the timing (antenatal, birth, 6 months, or age 5 years) – that predicted poorer child receptive language skills. Because mediation is best examined with different longitudinal datapoints, we opted to use MDS symptoms at 9 months only. Longitudinal effects of maternal depression on parenting behaviors are observed even after remission (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare and Neuman2000). Further research however will help to determine how the timing, severity, and/or chronicity of MDS across infancy and early childhood relates to language development.

Conclusion

The current findings support a mediation pathway from MDS to child language through parent-child verbal interaction. Importantly, our measurement of both self-reported and observed parent-child verbal interactions strengthens confidence that findings are not confounded by shared measurement bias due to maternal report. Children’s language ability underlies later academic, cognitive, social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. By the time children start school, these differences are relatively entrenched. The current findings highlight the early developmental origins of differences in child language ability and highlight the importance of early identification and intervention for MDS and related parent-child interactions in the preschool years. Beyond the dyad and family system, children in more socioeconomically deprived areas are at greater risk, suggesting a need to effectively and comprehensively target resources towards our most vulnerable families in order to improve inequities in cognitive outcomes.

Funding statement

Growing Up in New Zealand has been funded over time by New Zealand government ministries. These include the Ministries of Social Development, Health, Education, Justice, and Pacific Island Affairs; the former Ministries of Science Innovation and of Women’s Affairs; the former Department of Labour; the Department of Corrections; Te Puni Kokiri; and New Zealand Police. Growing Up has also received funding support from The University of Auckland and Auckland UniServices Limited.

Competing interests

None.