Introduction

Bullying is widely regarded as a serious personal and social problem that affects a substantial portion of youth. Involvement in bullying—either as a perpetrator or victim—has been linked to numerous developmental consequences (Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Wolke, Angold and Costello2013; Gini & Pozzoli, Reference Gini and Pozzoli2009; Ttofi et al., Reference Ttofi, Farrington and Lösel2012; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Lereya, Zanarini and Wolke2012). Bullying can create emotional distress for victims in the short-term and can also inflict more serious psychological harms that persist over time (Leadbeater et al., Reference Leadbeater, Thompson and Sukhawathanakul2014; Ttofi et al., Reference Ttofi, Farrington, Lösel and Loeber2011). Youth who bully others, too, experience adverse consequences, as they may enjoy exercising power and status over victims or fail to develop empathy for others (Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Van Noorden et al., Reference Van Noorden, Haselager, Cillessen and Bukowski2015; Volk et al., Reference Volk, Provenzano, Farrell, Dane and Shulman2021)—factors that may place them on a life-course trajectory toward crime and violence (Jolliffe & Farrington, Reference Jolliffe and Farrington2004; Klomek et al., Reference Klomek, Sourander and Elonheimo2015).

Among the most documented consequences of bullying perpetration and victimization are internalizing symptoms (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Newton, Stapinski, Slade, Barrett, Conrod and Teesson2015; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010; Schoeler et al., Reference Schoeler, Duncan, Cecil, Ploubidis and Pingault2018; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Lansford, Dodge, Pettit and Bates2015). Internalizing symptoms typically encompass emotional and psychological problems such as sadness, hopelessness, anxiousness, loneliness, and low self-esteem. These symptoms are concerning given their direct and indirect links to additional health and behavioral problems, such as suicidality, substance use, and delinquency (Bender et al., Reference Bender, Postlewait, Thompson and Springer2011; Duke et al., Reference Duke, Borowsky, Pettingell and McMorris2011; Egerton et al., Reference Egerton, Jenzer, Blayney, Kimber, Colder and Read2020). Importantly, internalizing symptoms are not only consequences of bullying, but they can also serve as predictors of bullying perpetration and victimization (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019). Research shows that youth with internalizing problems are more likely to be victimized by their peers (Acquah et al., Reference Acquah, Topalli, Wilson, Junttila and Niemi2016; Schacter et al., Reference Schacter, White, Chang and Juvonen2015; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Prinzie and Salmivalli2017), and that youth who exbibit symptoms of lower self-worth and poor emotional adjustment have higher risks of bullying perpetration and victimization (Choi & Park, Reference Choi and Park2018; Fanti & Henrich, Reference Fanti and Henrich2015; Farrington & Baldry, Reference Farrington and Baldry2010).

Although the longitudinal, bidirectional associations between internalizing symptoms and bullying perpetration and victimization have been documented, research is limited on the mechanisms that explain these associations (Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010). Given the salience of peer relationships during adolescence, in this study we focus on social support from friends as one potential mechanism. Specifically, we propose that bullying perpetration and victimization evoke negative peer reactions that undermine the formation of close, supportive friendships; that this lack of support should increase levels of internalizing problems, as youth without positive peer relationships are more likely to develop emotional and psychological difficulties; and that reduced friend support and internalizing problems contribute to more bullying perpetration and victimization, thus perpetuating a harmful cycle of repeat bullying, reduced support, and internalizing problems.

In carrying out this exploratory research, we draw from a transactional framework that is inclusive of reciprocal dynamics between individuals and their social contexts (Sameroff & MacKenzie, Reference Sameroff and Mackenzie2003; Troop-Gordon et al., Reference Troop-Gordon, Schwartz, Mayeux, McWood and Halpern-Felsher2021)—recognizing that bullying, internalizing problems, and friend support can be mutually reinforcing and contribute to a cascade of adjustment problems over the course of adolescence (Busch et al., Reference Busch, Laninga-Winjen, van Yperen, Schrijvers and De Leeuw2015; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013). Such an approach moves beyond the identification of one-directional paths to explore more complex bidirectional associations of bullying perpetration and victimization on internalizing symptoms and friend support.

Background

Friendships in adolescence

Supportive peer relationships are pivotal to youth wellbeing. Particularly in adolescence, youth rely on peers to receive comfort, companionship, and validation, and friendships are a primary source of adjustment and fulfillment (Crosnoe, Reference Crosnoe2000; Erwin, Reference Erwin2013; Hartup & Stevens, Reference Hartup and Stevens1997). Difficulties in peer relationships often co-occur with social exclusion, various forms of bullying and victimization, and psychosomatic symptoms during the teen years (Bagwell & Bukowski, Reference Bagwell, Bukowski, Bukowski, Laursen and Rubin2018; Troop-Gordon et al., Reference Troop-Gordon, MacDonald and Corbitt-Hall2019). Indeed, a wealth of research suggests that the failure to cultivate high-quality peer relationships can jeopardize youths’ short-term and long-term emotional development (Marion et al., Reference Marion, Laursen, Zettergren and Bergman2013; Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Bowker, McDonald, Menzer and Zelazo2013; Turner, Reference Turner1999).

Previous studies have examined various dimensions of high-quality friendships, including social integration, friendship reciprocation, peer acceptance, friendship closeness, and—especially relevant to this study—friend support. Despite emphasis on the importance of quality friendships, little is known about how levels of friend support contribute to cascading problems of bullying perpetration, victimization, and internalizing symptoms throughout adolescence. For the most part, research has documented the longitudinal, reciprocal associations between bullying and internalizing problems (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Da Silva et al., Reference Da Silva, Gonzalez, Person and Martins2020), without considerable attention paid to the explanatory factors that underlie these dynamic associations. As such, much remains unclear about the extent to which support from friends acts as a bidirectional mediating mechanism between bullying and internalizing symptoms for youth. In what follows, we situate friend support as a predictor and consequence of bullying perpetration, victimization, and internalizing symptoms, and then further discuss its potential role as a mediating factor within a transactional framework. We also reference related findings on analogous dimensions of friendships.

Bullying perpetration, victimization, and friend support

Bullying includes targeted humiliation or intimidation, typically when physically stronger or more socially prominent youths use their power to threaten, demean, or belittle others (Brank et al., Reference Brank, Hoetger and Hazen2012; Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Olweus, Reference Olweus1993). Importantly, bullying cannot be adequately understood separately from the peer context in which it occurs. It reflects a dynamic interaction and power imbalance between the perpetrator and victim, wherein the power imbalance between parties distinguishes bullying from other forms of interpersonal conflict. Bullying is also thought to be rooted in motives for social dominance, wherein bullies resort to coercive strategies to elevate their standings within peer social hierarchies (Cillessen & Mayeux, Reference Cillessen and Mayeux2004; Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Sijtsema et al., Reference Sijtsema, Veenstra, Lindenberg and Salmivalli2009).

Status enhancement is particularly important during adolescence. There tends to be a robust association between aggression and social prominence in many peer networks (Faris & Felmlee, Reference Faris and Felmlee2011; Neal, Reference Neal2010), even though bullies tend to be disliked and have more brittle, shallow friendships (Garandeau & Lansu, Reference Garandeau and Lansu2019; Kisfalusi et al., Reference Kisfalusi, Hooijsma, Huitsing and Veenstra2022). Moreover, marginalized youth who operate on the fringes of social networks—those who have little support from friends—tend to be those who are the victims of more prolonged and serious forms of bullying. Being the victim of bullying is often associated with decreases in social status and increases in alienation (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Lansford, Agoston, Sugimura, Schwartz, Dodge and Bates2014; Salmivalli & Isaacs, Reference Salmivalli and Isaacs2005).

Typically, research has assessed friend support (or the lack thereof) as a predictor of bullying perpetration or victimization. For example, a cooperative learning intervention was found to reduce peer victimization by fostering the formation of high quality—that is, reciprocated—friendships (Van Ryzin et al., Reference Van Ryzin, Roseth, Low and Loan2022). Studies generally show that youth with more supportive and higher quality friendships are less likely to be involved in bullying, either as a perpetrator or victim (Hodges et al., Reference Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro and Bukowski1999; Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Jutengren and Stattin2012). This is likely because supportive friendships coincide with enhanced self-esteem, better social skills, fewer problem behaviors, and the willingness to protect and defend one another (Boulton et al., Reference Boulton, Trueman, Chau, Whitehand and Amatya1999; Malcolm et al., Reference Malcolm, Jensen-Campbell, Rex-Lear and Waldrip2006; Maunder & Monks, Reference Maunder and Monks2019)—all of which can reduce the likelihood of bullying others or being the victim of bullying.

Comparatively less research has examined friend support as an outcome of bullying (Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Jutengren and Stattin2012), although several studies have documented numerous peer-based consequences of aggression and victimization. These include social exclusion and peer rejection, which are closely related to decreases in friend support (Hanish & Guerra, Reference Hanish and Guerra2002; Kawabata et al., Reference Kawabata, Tseng and Crick2014; Salmivalli & Isaacs, Reference Salmivalli and Isaacs2005). Such research has shown, for example, that bullies and victims are viewed less favorably by peers and tend to be more disliked; and that bullying perpetration and victimization tend to increase subsequent peer rejection and reduce peer acceptance (Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Vermande, Olthof, Goossens, Van De Schoot, Aleva and Van Der Meulen2013; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Dijkstra, Salmivalli and Cillessen2013, Reference Sentse, Kretschmer and Salmivalli2015).

According to Sentse et al. (Reference Sentse, Kretschmer and Salmivalli2015), peers may not want to associate with youth who are victimized or who bully others because they tend to be low in the social structure of the peer group. This may contribute even further to victimization and bullying for socially excluded youth. Indeed, longitudinal research has confirmed that negative, bidirectional associations exist between peer acceptance and bullying (e.g., Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Kretschmer and Salmivalli2015) and between peer liking and victimization (e.g., Kawabata et al., Reference Kawabata, Tseng and Crick2014). As such, there are likely reciprocal links between bullying and friend support, wherein supportive peer relationships can influence, and be influenced by, bullying perpetration and victimization.

Friend support and internalizing symptoms

Beyond bullying, psychosocial distress stemming from peer relationships can be a powerful predictor of internalizing symptoms (Thapar et al., Reference Thapar, Collishaw, Pine and Thapar2012). As adolescents increasingly spend more time with their peers and invest significant energy into friendships (Brown, Reference Brown, Lerner and Steinberg2004; Steinberg & Morris, Reference Steinberg and Morris2001) issues such as losses in friend support can result in negative emotional difficulties. Close, quality friendships can also serve as an important source of self-worth, whereas friendships that are not characterized by intimacy or support can be emotionally troublesome (Maunder & Monks, Reference Maunder and Monks2019; Waldrip et al., Reference Waldrip, Malcolm and Jensen-Campbell2008). Numerous data sources show that problems such as peer rejection and ostracism result in internalizing symptoms including increases in negative mood and anxiety, increases in depressive symptoms, and decreases in self-esteem (Platt et al., Reference Platt, Kadosh and Lau2013; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Stegge, Terwogt, Kamphuis and Telch2006; Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Tan, Roiser, Viding, Dumontheil and Blakemore2011).

What is more, internalizing symptoms—once present—can also result in further decreases in friend support. Research documents that risks for peer rejection, avoidance, and social exclusion are increased for adolescents who suffer from internalizing problems—in part because such youth tend to withdraw from others and become excluded from the broader peer group (Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Kornienko and Fox2011). Symptoms related to depression and other internalizing problems, such as self-criticism, self-doubt, sadness, guilt, and anxiousness, can each reduce one’s investment in forming and maintaining friendships. According to Schaefer et al. (Reference Schaefer, Kornienko and Fox2011), youth who suffer from internalizing problems may also view themselves as less competent or incapable of providing emotional support to others. As a result, these youth “withdraw from relationships rather than receive support and incur an obligation they cannot repay” (Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Kornienko and Fox2011, p. 768). Thus, while friend support can serve as a negative predictor of internalizing symptoms, reciprocal relationships between friend support and internalizing symptoms are also likely to be present.

Bullying, friend support, and internalizing symptoms

Taken together, research suggests that bullying perpetration and victimization can lead to decreases in friend support, which can lead to increases in internalizing symptoms, especially as bullies and victims may experience dislike or alienation from the broader peer group. Likewise, internalizing symptoms can decrease friend support, and thus may indirectly increase involvement in bullying, as a perpetrator or victim. To best account for the cascading influences of bullying, friend support, and internalizing symptoms on youth, we adopt a transactional model that explicitly acknowledges the dynamic interplay between individuals and their social contexts (Sameroff & MacKenzie, Reference Sameroff and Mackenzie2003; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Prinzie and Salmivalli2017; Troop-Gordon et al., Reference Troop-Gordon, Schwartz, Mayeux, McWood and Halpern-Felsher2021).

A transactional approach differs from a unidimensional model by conceptualizing continuous or bidirectional influences between youths’ problems and their relationships with peers. Such an approach recognizes, for example, that bullying may trigger negative peer reactions (e.g., decreases in friend support) which can contribute to internalizing symptoms, and more involvement in bullying, and so on. By specifying friend support as a key mechanism that links bullying involvement to internalizing symptoms, a transactional approach also allows for a deeper understanding of the ways to interrupt harmful cyclical processes from continuing throughout adolescence.

Our conceptual approach extends previous bidirectional models of youth problem development by incorporating an environmental mediator (friend support) that might account for those bidirectional relationships (Sameroff & MacKenzie, Reference Sameroff and Mackenzie2003). Although correlations between bullying involvement and internalizing symptoms have been previously identified, rarely have potential explanatory factors been modeled. Our proposed mediator has two notable features. First, it captures an element of the function of peer relations, an environmental domain that becomes increasingly salient during adolescence. Second, it adopts a dynamic rather than a static conceptualization of environmental influences (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2000). Specifically, under our model, friend support is potentially influenced by bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and internalizing symptoms. In this respect, youth are not passive subjects of environmental influence, but rather help shape their environments through their behaviors and emotional states. This active shaping of individual youths’ local peer contexts might help explain the co-occurrence of these problems during adolescence.

Current study

Based on the literature, we posit that friend support, bullying perpetration, and victimization are mutually reinforcing, culminating in direct and indirect pathways to internalizing symptoms and further bullying. Accordingly, the current study is an exploratory test of these ideas and has two primary goals. The first goal is to examine the prospective associations from bullying perpetration, victimization, and internalizing symptoms to perceived friend support, as well as the prospective associations from perceived friend support to bullying perpetration, victimization, and internalizing symptoms. The second goal is to test for indirect links from bullying perpetration and victimization to internalizing symptoms through perceived friend support, as well as indirect links from internalizing symptoms to bullying perpetration and victimization through perceived friend support.

We include both bullying perpetration and victimization given that the two phenomena overlap substantially, such that one cannot be adequately understood without the other (Cho, Reference Cho2017; Paez & Richmond, Reference Paez and Richmond2022; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Kretschmer and Salmivalli2015). However, due to the important distinctions between those who perpetrate bullying and those who are victims of it, we examine bullying victimization and perpetration as separate constructs (Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Turanovic et al., Reference Turanovic, Pratt, Kulig and Cullen2022). By testing for bidirectional and indirect associations between bullying involvement, internalizing symptoms, and friend support, this research has the potential to provide deeper insights into the development of psychopathology and peer maladjustment throughout the adolescent years.

To accomplish the study goals, we use a recent extension of the cross-lagged panel models that have been used extensively in prior research on this subject (e.g., Pabian & Vandebosch, Reference Pabian and Vandebosch2016; Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Prinzie and Salmivalli2017; Troop-Gordon et al., Reference Troop-Gordon, MacDonald and Corbitt-Hall2019). Although those models can identify prospective correlational associations between constructs, their estimates are vulnerable to bias from stable trait-like differences between respondents, and they do not account for underlying developmental trends (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane and McGinley2014). This is problematic for two reasons. First, the theoretical logic behind the associations between our key constructs involves the ability of each focal construct to produce changes in the others. As such, empirical tests of these hypothesized relationships ideally would include a focus on change rather than on stable traits. Second, parceling out the influence of stable traits in cross-lagged panel modeling can change studies’ substantive findings (e.g., Fredrick et al., Reference Fredrick, Nickerson and Livingston2021; Mastrotheodoros et al., Reference Mastrotheodoros, Canário, Gugliandolo, Merkas and Keijsers2020). Our method thus represents one of the most rigorous tests to date of the mutual influences among bullying, internalizing symptoms, and friend support.

Method

Data

The data came from the PROmoting School-community-university Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) study, a longitudinal survey study of adolescents in 28 school districts in Pennsylvania and Iowa (Spoth et al., Reference Spoth, Greenberg, Bierman and Redmond2004; Spoth et al., Reference Spoth, Redmond, Shin, Greenberg, Feinberg and Schainker2013). PROSPER included school districts that enrolled between 1,300 and 5,200 students, and had student populations with at least 15% of families eligible for free or reduced cost school lunch. PROSPER’s original purpose was to test a delivery system for substance use prevention programming, and half of the districts were randomly assigned to receive such programming. Intervention condition was not significantly related to our focal variables (see Appendix A), so we use data from both conditions and control for condition in our models.

PROSPER sampled two successive cohorts of students who completed wave 1 in-school surveys in the fall of 6th grade (in 2002 and 2003) and follow-up in-school surveys each spring from 6th through 12th grade. Alongside the in-school surveys, five waves (6th through 9th grades) of in-home family assessments were conducted with randomly selected and recruited families of 6th graders from the second cohort of students. Prior analyses revealed that the in-home participants resembled the in-school sample on factors such as demographic characteristics and substance use but were slightly less delinquent, indicating that they were at slightly lower risk for problem behavior (Fosco & Feinberg, Reference Fosco and Feinberg2015; Lippold et al., Reference Lippold, Greenberg and Feinberg2011). For this reason, delinquency was included as a control variable in the current analyses.

From the 2,267 families that were targeted for recruitment for the in-home portion of the study, 980 (43%) youth completed at least one in-home interview. The first four (6th–8th grade) interviews were used in this study; the 9th grade data were not used due to additional attrition and the fact that most students experienced a school transition, which could have impacted our focal variables, at that grade. One in-home respondent did not begin participating until 9th grade; the remaining 979 respondents were our analytical sample. Of those respondents, 689 (70%) completed all four of the interviews used here. We examined how respondents who did and did not participate in all four waves differed from each other. The 27 examined covariates measured several domains including demographics, mobility, peer characteristics, family relations, deviant behavior, socioeconomic status, school attachment and aspirations, and physical and emotional health. Of these covariates, only four were associated with attrition. Respondents who completed all waves were more likely to be white, were less likely to have moved schools before wave 1, had parents with higher levels of education, and received more parental monitoring. Among waves at which respondents participated, rates of item-missing data were low (average missingness = 1%). Missing interviews and item-missing data were handled via full information maxium likelihood estimation, which has been shown to reduce bias resulting from non-participation (e.g., Enders, Reference Enders2001).

Measures

Bullying perpetration

At each wave, respondents reported how often they had put down someone to their face, spread a false rumor about someone, picked on someone, excluded another student from their group, insulted someone’s family, started a fight between other people, beat up or physically fought with someone because they made them angry, or thrown objects such as rocks or bottles at people to hurt or scare them (α = .75, .77, .79, and .78 at waves 1 through 4, respectively). Respondents indicated the raw number of times they had done each act; scores above 98 were represented as 98 in the data. Few respondents reported doing these acts more than one to three times. For example, 10% picked on someone four or more times, 5% reported putting someone down four or more times, 5% reported excluding someone four or more times, 2% reported starting fights four or more times, 2% reported beating someone up four or more times, and 1% or fewer of respondents reported doing the other acts four or more times. Because the items had very low frequencies at higher counts, the raw counts were recoded into ordinal variables (0 = never, 3 = 4 or more times). The mean of the recoded items at a given wave was used as that wave’s measure of bullying perpetration.

Bullying victimization

At each wave, respondents reported how often someone had pushed or shoved them, stolen or destroyed their things to be mean, teased or insulted them, told rumors or lies about them, or ignored them or kept them out of a group (1 = never, 4 = always; α = .84, .81, .81, and .76 at waves 1 through 4 respectively). These items are derived from the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Solberg & Olweus, Reference Solberg and Olweus2003). The mean of these items at a given wave was used as that wave’s measure of bullying victimization.

Internalizing symptoms

Each wave’s survey also included 11 items from the Internalizing subscale of the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Dumenci, Reference Achenbach and Dumenci2001; Achenbach et al., Reference Achenbach, Dumenci and Rescorla2003). Items tapped whether in the past six months respondents had cried a lot, were afraid they might think or do something bad, felt they had to be perfect, felt no one loved them, felt worthless or inferior, felt nervous or tense, were too fearful or anxious, felt too guilty, were self-conscious or easily embarrassed, thought about killing themselves, or worried a lot (0 = not true, 2 = very or often true; α = .83, .83, .85, and .86 at waves 1 through 4, respectively). The mean of these items at a given wave was used as that wave’s measure of internalizing symptoms.

Perceived friend support

Each wave’s survey included eight items from a modified version of the Friendship Quality Questionnaire—Revised (Parker & Asher, Reference Parker and Asher1993). Respondents reported whether their friends cared about them, didn't listen to them, or stuck up for them when they were being teased; whether they and their friends got mad at each other a lot, or argued a lot; and whether they could talk to their friends when they were having a problem, count on their friends when they needed them, and count on them to keep their promises (1 = not at all true, 5 = really true; α = .76, .76, .79, and .82 at waves 1 through 4, respectively). The negative items (e.g., “my friends don't listen to me”) were reverse coded, and the mean of a given wave’s items was used as that wave’s measure of friend support.

Covariates

The analysis also controlled for intervention condition (0 = control, 1 = intervention), male gender (0 = not male, 1 = male), white race/ethnicity (0 = other race/ethnicity, 1 = white), the respondent’s school grades at wave 1 (1 = mostly Fs, 9 = mostly As), and wave 1 delinquency (the average of 9 items representing counts of the number of times the respondent had committed various forms of theft, property damage, or burglary or had been picked up by the police in the past year; α = .58). Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for the study variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for study variables

Analytical strategy

The hypotheses were tested using a variant of the latent curve model with structured residuals (LCM-SR; see Curran et al., Reference Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane and McGinley2014 for a discussion). Latent curve models estimate individual differences in both intercepts—the time-stable portion of an outcome—and slopes—the developmental trend in an outcome. LCM-SRs are multilevel extensions of latent curve models that isolate the within-person associations between constructs. To do this, LCM-SRs combine the latent curve model with a cross-lagged panel model. Rather than estimating autoregressive and cross-lagged paths among the observed variables themselves, in the LCM-SR these paths are estimated among the variables’ residuals. This ensures that the paths capture the associations among the constructs after between-person differences in the overall means and developmental trends in those constructs have been separated out. That is, because the residuals represent deviations of the observed measures from their underlying trajectories, regressions among them are equivalent to within-person analyses that account for developmental trends (Curran et al., Reference Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane and McGinley2014). These analyses thus ensure that the estimated cross-lagged associations are not spurious to the influence of the stable traits or developmental trends, thus improving causal inference.

The model was built using Mplus 8.8 in four steps. First, we examined the developmental trends in each of the four focal constructs; in the final path model linear trends were included for internalizing symptoms, bullying victimization, and friend support, and linear and quadratic functions were included for bullying perpetration. Second, a substantive model was specified, featuring autoregressive paths among and cross-lagged paths between the residuals as well as paths from the time-invariant controls to the latent intercepts and slopes. Third, in a series of models and accompanying tests of change in model fit, we tested whether each autoregressive and cross-lagged path could be constrained across waves without worsening model fit. Nearly all could, but constraining the autoregressive path for perpetration worsened model fit. In the final model this path was freely estimated, and the others were constrained.

Fourth, eight tests of indirect effects between bullying and internalizing symptoms through friend support were specified. These were specified via Mplus’ model indirect command, which computes indirect effects as the product of the regression coefficients between the independent variable and mediator and the mediator and dependent variable. Two of the tests assessed indirect paths from perpetration to later internalizing symptoms (at waves 1 and 3 via wave 2 support and at waves 2 and 4 via wave 3 support), two tested for indirect paths from victimization to later internalizing symptoms (at the same combinations of waves), two tested for indirect paths from internalizing symptoms to later perpetration, and two tested for indirect paths from internalizing symptoms to later victimization. Because the pathways between pairs of constructs were constrained, the analogous tests of mediation from waves 1 to 3 and waves 2 to 4 were identical; thus only four mediation results are described below. The “c” paths in each direction between the ultimate independent and dependent variables (i.e., bullying/internalizing and internalizing/bullying two years later) were also included in the model and were constrained to be equal across time. The cross-lagged paths and tests of indirect effects yielded this study’s results of interest.

The final model included bootstrapping (5,000 replications) and allowed for within-wave correlations between the residuals. Because respondents were sampled from communities, we adjusted our standard errors for the sampling design by including community as a clustering factor. Model fit indices indicated that the model had an acceptable fit (LL = −8733.992; SRMR = 0.045; Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Moshagen, Reference Moshagen2012; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Lee and Maydeu-Olivares2019; West et al., Reference West, Taylor, Wu and Hoyle2012). More fit indices were available without bootstrapping, and these too were acceptable (RMSEA = 0.041; CFI = 0.930).

Results

Autoregressive and cross-lagged associations between bullying, internalizing, and support deviation scores

Table 2 shows the unstandardized results of the path model (standardized estimates are noted in the text below). All autoregressive parameters were positive and significant, indicating that respondents’ deviations from their developmental trends on each construct in one wave positively predicted their deviations on the same construct at the following wave.

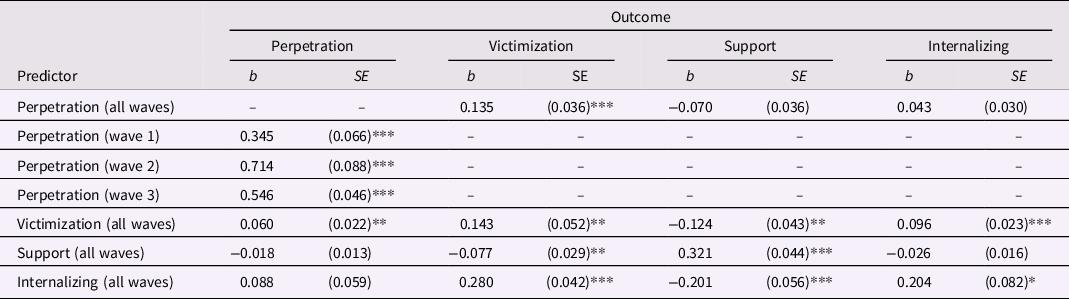

Table 2. Results of a latent curve model with structured residuals estimating autoregressive and cross-lagged pathways between bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, internalizing symptoms, and perceived friend support

Note. Estimates represent associations between the predictor at a given wave and the outcome at the following wave. Constrained paths are given in “all waves” rows; paths that were allowed to vary by wave are given in wave-specific rows. The model also included paths from victimization to internalizing two waves later (b = 0.032, p > .05), perpetration to internalizing two waves later (b = 0.043, p > .05), internalizing to victimization two waves later (b = 0.149, p < .05), and internalizing to perpetration two waves later (b = 0.178, p < .01).

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

More important for our research questions are the cross-lagged associations between the residuals. These estimates yielded two main findings. First, we found consistent bidirectional associations between bullying perpetration and bullying victimization, between victimization and perceived friend support, and between victimization and internalizing symptoms. Respondents who experienced higher than usual bullying perpetration scores at one wave went on to experience higher than usual bullying victimization at the following wave (standardized β ∼ 0.12), and victimization scores at one wave predicted higher than usual perpetration at the next wave (standardized β ∼ 0.06). Higher than usual victimization scores at one wave predicted lower than usual friend support at the next (standardized β ∼ −0.10), and vice-versa (standardized β ∼ −0.09). In addition, higher than usual victimization scores predicted higher than usual internalizing scores (standardized β ∼ 0.18), and vice versa (standardized β ∼ 0.15). These were all small associations by conventional standards, though they were moderate in size in relation to the effect sizes typically found in cross-lagged models (Orth et al., Reference Orth, Meier, Bühler, Dapp, Krauss, Messerli and Robins2022).

Second, although higher than usual internalizing symptoms had a modest negative association with later perceived friend support (standardized β ∼ −0.09), there was no significant association in the opposite direction. Third, there were limited significant associations in either direction between bullying perpetration and perceived friend support, or between bullying perpetration and internalizing symptoms. The one significant association in the model involved internalizing symptoms predicting perpetration two waves later; yet the analogous association over one wave was not significant.

Mediation of longitudinal pathways by friend support

The lack of prospective associations from friend support to internalizing symptoms, from perpetration to friend support, and from friend support to perpetration limit the chances for friend support to mediate the longitudinal associations between bullying and internalizing symptoms. The limited prospective associations between perpetration and internalizing symptoms indicate that any longitudinal mediation would be more likely to be found for the internalizing–victimization pathway. Still, tests of indirect effects were conducted to determine whether changes in bullying perpetration and victimization and changes in internalizing symptoms influenced each other indirectly through their influences on changes in perceived friend support. To reiterate, these analyses examined support as a mediator of the perpetration to internalizing path, the victimization to internalizing path, and each analogous path in the other direction (i.e., from internalizing to bullying perpetration and victimization). None of the tests were statistically significant.

Discussion

Theoretically, bullying involvement and internalizing symptoms can trigger each other through their negative effects on social support. This study tested a transactional model of mutually reinforcing pathways between these problems during adolescence that are mediated by supportive friendships. We reasoned that bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and internalizing symptoms should be positively and prospectively related, that these relationships should be bidirectional, and that decreases in perceived friend support should help to explain them. Such associations would be evidence of cascading consequences of specific youth problems into other domains of adjustment (Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Brittain, McDougall and Duku2013) and would increase our understanding of how these cascades occur. This study used a particularly stringent statistical method that isolated the associations between changes in these key constructs over time and eliminated the influence of time-stable traits, developmental trends, and other time-stable sources of spuriousness.

Degree of support for the proposed transactional model

We found limited support for the transactional model, including its mediation hypothesis. Regarding the expectations that were confirmed, support was found for reciprocal associations between internalizing symptoms and bullying victimization. This confirmation of paths identified in past work (e.g., Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021) is notable because here those paths were found under stricter adjustments for selection than what have conventionally been used. The analyses also provided new and stringent evidence for a bidirectional negative association between victimization and perceived friend support. This aligns with past research, which has focused on the former direction of effects—that is, from support to bullying involvement (e.g., Hodges et al., Reference Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro and Bukowski1999; Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Jutengren and Stattin2012)—but which also has linked peer victimization with peer exclusion and rejection (Hanish & Guerra, Reference Hanish and Guerra2002; Kawabata et al., Reference Kawabata, Tseng and Crick2014; Salmivalli & Isaacs, Reference Salmivalli and Isaacs2005). These paths together provide an initial foundation for examining potential transactional mediators of these bidirectional associations.

Despite this suggestive evidence for the full hypothesized causal path, the indirect effects analyses revealed no support for the proposed mediation model. This was due to several factors. First, perceived friend support did not prospectively predict internalizing symptoms. Second, support did not predict later bullying perpetration, nor did perpetration predict later support. This meant that an indirect path involving bullying perpetration was unlikely. Third, under our strict analytic strategy, bullying perpetration had little association with internalizing symptoms. This meant that there was little chance that we would find longitudinal mediation of such a path via friend support. Thus, the main reason why the proposed model was not supported was the failure to find several of the bivariate associations that had been hypothesized.

As further evidence against the proposed model, we found that perceived friend support did not explain the significant bidirectional associations between bullying victimization and internalizing symptoms. Of the eight indirect paths tested, the internalizing-support-victimization path came closest to statistical significance (p = 0.063), but it did not reach the conventional threshold for significance. This means that reduced friend support may not be the reason why victims of bullying experience more internalizing problems or why youth with internalizing symptoms experience more peer victimization. These findings are in contrast with related work on other dimensions of adolescent peer relations, such as peer rejection (e.g., Sentse et al., Reference Sentse, Prinzie and Salmivalli2017). It could be the case that perceived friend support is a qualitatively distinct aspect of peer relations that is more often an outcome of than a precursor to adolescent problems such as bullying and internalizing symptoms. Future research should therefore consider how different dimensions of peer and friendship relations are distinct from each other, and whether they are differentially related to bullying involvement.

As noted above, one reason why our transactional model was not supported involves the lack of a significant pathway from perceived friend support to internalizing symptoms. Although peer rejection has been shown to increase internalizing symptoms (Platt et al., Reference Platt, Kadosh and Lau2013; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Stegge, Terwogt, Kamphuis and Telch2006; Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Tan, Roiser, Viding, Dumontheil and Blakemore2011), perceived friend support does not appear to have the inverse effect. This suggests that there are other, more important mediators of the bidirectional associations between our focal constructs. Still, the non-significant estimated path in this study captured the association between support and internalizing symptoms for the entire sample, and there is suggestive evidence that any association may be specific to victimized youth (Houlston et al., Reference Houlston, Smith and Jessel2011; Woods et al., Reference Woods, Done and Kalsi2009). If perceived friend support is a moderator rather than a mediator of the broader paths found in this study, then it implies that the transactional model should be replaced with a vulnerabilities model that identifies the social characteristics of youth who are most likely to experience negative consequences of their involvement in bullying, or of their internalizing symptoms. Future research should examine this possibility.

The internalizing-support and victimization-support paths that we did find confirm past work showing that youth with internalizing symptoms withdraw from friendships (Schaefer et al., Reference Schaefer, Kornienko and Fox2011) and that victimized youth are at greater risk for social marginalization (Kawabata et al., Reference Kawabata, Tseng and Crick2014). This establishes reduced perceived support as one of a range of peer-related outcomes that follow from a diverse set of adverse adolescent experiences. Our finding that youth problems predict friend support more often than friend support predicts youth problems is in contrast with the typical approach to this topic, which has tended to consider support as a source of other outcomes (e.g., Hodges et al., Reference Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro and Bukowski1999; Kendrick et al., Reference Kendrick, Jutengren and Stattin2012; Platt et al., Reference Platt, Kadosh and Lau2013; Poulin & Chan, Reference Poulin and Chan2010; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Stegge, Terwogt, Kamphuis and Telch2006; Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Tan, Roiser, Viding, Dumontheil and Blakemore2011). Future research should continue to explore perceptions of peer relations as important outcomes in their own right.

Finally, we found that bullying perpetration did not predict, and generally was not predicted by, perceived friend support and internalizing symptoms. This is in contrast with work that has linked support to factors that should reduce bullying perpetration, such as self-esteem and social skills (e.g., Maunder & Monks, Reference Maunder and Monks2019). It also is in contrast with work suggesting a bidirectional association between perpetration and emotional problems (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Merrin, Ingram, Espelage, Valido and El Sheikh2019; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Newton, Stapinski, Slade, Barrett, Conrod and Teesson2015). However, the relative lack of prospective associations under our rigorous statistical method does not mean that bullying perpetration does not co-occur with internalizing symptoms and friend support. The well-documented contemporaneous correlations among these constructs reaffirm the need for interventions that address multiple associated risk behaviors and outcomes, as youth who experience more than one of these problems might be at especially high risk for long-term negative sequalae. The outcomes of such multiple-problem youth, as well as ways to ameliorate those outcomes, remain important priorities for research and practice.

Theoretical implications

The current findings have implications for our understanding of both developmental cascades and person–environment transactions. Our longitudinal data and statistical method allowed us to identify spreading or diffusing associations among adjustment problems across a three-and-a-half-year period: Bullies (victims) went on to be victims (bullies), victims experienced elevated internalizing symptoms, and symptoms triggered additional victimization.

Like us, previous authors have offered interpersonal explanations for the co-occurrence of bullying involvement and internalizing problems. For instance, some theories of bullying emphasize perspective-taking and the ability to “read” people, either of which might be compromised by depression and anxiety symptoms (e.g., Crick & Dodge, Reference Crick and Dodge1994; Morningstar et al., Reference Morningstar, Dirks, Rappaport, Pine and Nelson2019). These theories are compatible with our original formulation of a transactional model mediated by friend support, and they are indirectly supported by evidence that errors in social cognition help explain the associations of internalizing symptoms with other forms of aggression (e.g., Marsee et al., Reference Marsee, Weems and Taylor2008). In the current case, internalizing symptoms predicted only vulnerability to aggression from peers, not aggression against peers. These results would be partially consistent with interpersonal theories of depression that link peer difficulties to maladaptive responses to social situations—responses that stem from depressive symptoms (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Flynn, Abaied, Abela and Hankin2008).

However, in contrast with these ideas, our measure of peer relations—perceived friend support—does not explain these developmental cascades. Although the examined youth problems do appear to alter this element of the local peer context, that association is not responsible for any long-term effects of one type of adjustment difficulty on another. We thus conclude that a general transactional approach to these problems has merit, but that perceived friend support is not the crucial mechanism behind the associations. Importantly, the bidirectional association between support and victimization suggests that enhancing peer support can protect against harmful peer experiences. This affirms the utility of studying friend support, even if that support does not explain why other adolescent problems co-occur.

Limitations and directions for future research

Even though this study used longitudinal data, validated measures, and stringent analyses, it also had limitations. First, all of the measures were self-reported by youth. The cognitive biases that accompany internalizing symptoms could have influenced youths’ reports of their bullying involvement, friend support, or even internalizing symptoms themselves. Future research should seek to replicate our findings using reports of these constructs that are obtained from independent sources. In addition, because our measures were not based on clinical diagnoses of internalizing disorders, our results do not necessarily apply to adolescents with clinical levels of depression or anxiety. Second, we examined friend support, whereas friendship quality, social exclusion, and peer rejection have received more attention in past theory and research on this topic. In one sense this is a contribution, as we provide evidence on an understudied dimension of peer relations, but it also is possible that support is not the most salient dimension for the transactional model that we examined. Future research should use similar methods to examine other aspects of friendships in relation to bullying and internalizing problems.

Third, while intervention condition was not associated with any of our focal variables, it is possible that it moderated some of the associations of interest. Although our sample of control condition youth was too small for us to examine them separately, and for the same reason we could not examine interactions with condition, future research should evaluate whether programs like those tested by PROSPER can reduce the associations that we found here. Fourth, some youth experienced school transitions during the study period (Temkin et al., Reference Temkin, Gest, Osgood, Feinberg and Moody2018), and those also could have moderated the observed associations. Studies should examine the persistence of these associations across school transitions, particularly associations involving constructs with strong links to school-based peer networks.

Finally, as noted earlier, there were differences between the sample used in this study and the PROSPER study’s larger in-school sample. In addition, the PROSPER data were collected in largely rural and predominately White areas with large proportions of low-income families. All of these factors could influence the generalizability of the results. Future research should examine whether similar patterns are present in different populations and contexts.

Conclusion

This study examined whether changes in bullying involvement and changes in internalizing symptoms predicted each other, and whether any predictive paths were mediated by changes in perceived friend support. The results were only partially consistent with a transactional model in which internalizing symptoms lead to bullying victimization and vice versa, and in which bullying victimization and friend support also reduce each other. Contrary to expectations, changes in perceived friend support were not associated with later changes in internalizing symptoms, and changes in bullying perpetration neither preceded nor followed changes in support or in internalizing symptoms. Future research should identify the mechanisms behind internalizing-bullying cycles, so that those cycles might be interrupted through prevention and intervention efforts. More generally, additional research is needed on the dynamic interplay between bullying, friend support, and internalizing problems across a wider span of adolescence.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Grants from the W. T. Grant Foundation (8316), National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA018225), and National Institute of Child Health and Development (R24-HD041025) supported the preparation of the data used in this research. The analyses used data from PROSPER, a project directed by R. L. Spoth, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA013709) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA14702).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Appendix A

Bivariate associations of intervention condition with the study variables

Note. Estimates are bivariate linear regression coefficients.