Approximately one in every three young people are victimized by peers at some point (Modecki et al., Reference Modecki, Minchin, Harbaugh, Guerra and Runions2014), and 10%–15% experience continued, chronic victimization across multiple years (Troop-Gordon, Reference Troop-Gordon2017). Such victimization can involve overt acts of aggression, such as verbal abuse and physical harassment, as well as covert forms of relational manipulation, such as rumor spreading and exclusion (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017). Experiences of peer victimization appear to be particularly emotionally taxing during adolescence, a developmental period during which youth become increasingly concerned with gaining peer acceptance while also exhibiting greater emotional reactivity to social stressors (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Wilson, Brown, Furstenberg and Verma2002; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler and Hilt2009). Indeed, decades of research have established that peer victimization, especially covert forms involving social manipulation and reputational damage (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017), has deleterious effects on adolescents’ mental health (Juvonen & Graham, Reference Juvonen and Graham2014; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010). In particular, peer victimization confers elevated risk for anxiety (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Fitzpatrick, Magson and Rapee2019), the most common psychiatric disorder across the lifespan (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Ruscio, Shear and Wittchen2010; Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Zinbarg, Seeley, Lewinsohn and Sack1997). Frequently victimized adolescents are two to three times more likely to develop an anxiety disorder compared to their non-victimized peers (Stapinski et al., Reference Stapinski, Bowes, Wolke, Pearson, Mahedy, Button, Lewis and Araya2014), and this risk persists into adulthood even after accounting for other forms of early adversity (e.g., child abuse, parent mental health problems; Copeland et al., Reference Copeland, Wolke, Angold and Costello2013). Moreover, adolescent-onset anxiety disorders, compared to adult onset, are associated with worse social functioning, more health risk behaviors, lower life satisfaction, and a greater probability of recurrence later in life (Bruce et al., Reference Bruce, Yonkers, Otto, Eisen, Weisberg, Pagano, Shea and Keller2005; Essau et al., Reference Essau, Lewinsohn, Olaya and Seeley2014). Anxiety is particularly prevalent among girls (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Gotlib, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Allen1998), and adolescents with anxiety are also more likely to develop other forms of psychopathology, such as depression or substance use disorders (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Zinbarg, Seeley, Lewinsohn and Sack1997). However, the mechanisms that account for associations between peer victimization and adolescent anxiety are not well understood, thus undermining the development of targeted prevention and intervention approaches that can interrupt such maladaptive pathways.

Growing research identifies the key role of aberrant sensitivity to threat in the development and maintenance of emotional disorders, making threat-detection processes a chief mechanistic and therapeutic target for anxiety (Grillon, Reference Grillon2008; Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Lissek, Rabin, McDowell, Dvir and Pine2008; Shechner et al., Reference Shechner, Britton, Pérez-Edgar, Bar-Haim, Ernst, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2012). Compared to non-anxious individuals, adults and adolescents with anxiety disorders demonstrate attention biases toward potential (i.e., ambiguous, unpredictable) threats, report greater perception of threat in ambiguous or uncertain situations, and show exaggerated physiological responses to potential threat (Fani et al., Reference Fani, Tone, Phifer, Norrholm, Bradley, Ressler, Kamkwalala and Jovanovic2012; Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Lissek, Rabin, McDowell, Dvir and Pine2008; Nelson & Hajcak, Reference Nelson and Hajcak2017). Such alterations in threat processing are typically observed before the emergence of anxiety symptoms and thus offer a key early marker for anxiety risk (Shechner et al., Reference Shechner, Britton, Pérez-Edgar, Bar-Haim, Ernst, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2012). Moreover, elevated attentional or physiological responses to threat are theorized to partially stem from early adversity, such as being the target of familial abuse (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Fani, Ressler, Jovanovic, Tone and Bradley2014; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019). Focusing largely on adverse early experiences, past studies have found that exposure to parental abuse, community violence, and harsh living conditions during childhood or adolescence confer risk for anxiety via alterations to underlying threat processing systems (Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Dierker and Merikangas1997; Jovanovic et al., Reference Jovanovic, Smith, Kamkwalala, Poole, Samples, Norrholm, Ressler and Bradley2011; Kliewer & Sullivan, Reference Kliewer and Sullivan2008). In particular, adversity-exposed youth are more likely to interpret ambiguous signals as threatening (Pine et al., Reference Pine, Mogg, Bradley, Montgomery, Monk, McClure, Guyer, Ernst, Charney and Kaufman2005; Sandre et al., Reference Sandre, Ethridge, Kim and Weinberg2018), and greater interpretations of threat in ambiguous stimuli are associated with variation in corticolimbic brain systems that are responsible for detecting, interpreting, and driving physiological responses to threat (Marusak et al., Reference Marusak, Zundel, Brown, Rabinak and Thomason2017). Moreover, heightened attention to threat partially mediates associations between early life physical abuse and anxiety (Herringa et al., Reference Herringa, Birn, Ruttle, Burghy, Stodola, Davidson and Essex2013; McLaughlin & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin and Lambert2017; Shackman et al., Reference Shackman, Shackman and Pollak2007), and interventions that train children to disengage attention from threat have been effective in reducing anxiety (e.g., Bar-Haim et al., Reference Bar-Haim, Morag and Glickman2011).

Despite mounting theoretical and empirical evidence that implicates threat sensitivity as a mechanism linking early adversity exposure to anxiety development, such work has largely focused on family- or community-based adversity experienced during childhood. In contrast, little is known about whether abnormalities in threat processing underlie pathways from peer victimization to anxiety among adolescents. Peer victimization represents a unique and emotionally impactful form of adversity during the adolescent years (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Wang, Pepler and Craig2020), and adolescents—compared to children or adults—exhibit distinct patterns of social-cognitive and affective processing that can contribute to anxiety risk. Specifically, maturation of the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) during adolescence contributes to increased motivation to understand others, greater self-consciousness, and heightened vigilance to (real or perceived) peer evaluation (Somerville, Reference Somerville2013). For example, compared to adults, adolescents exhibit greater recruitment of “social brain” regions (e.g., MPFC) when asked to consider the thoughts or intentions of others (Burnett et al., Reference Burnett, Sebastian, Cohen Kadosh and Blakemore2011). Additionally, compared to children and adults, adolescents experience greater embarrassment and exaggerated MPFC engagement when ostensibly being watched by a peer (Somerville, Reference Somerville2013). Together these findings suggest that adolescence is characterized by a heightened sensitivity to social evaluation and increased motivation to understand the feelings and intentions of others.

At the same time, adolescents also exhibit unique deficits in threat/safety discrimination, such that they experience difficulties differentiating between different degrees of threat (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Britton, Nelson, Angold, Ernst, Goldwin, Grillon, Leibenluft, Lissek, Norcross, Shiffrin and Pine2011). That is, emerging evidence suggests that adolescence is a sensitive period for the development of threat response regulation, such that heightened neural plasticity during this time can render adolescents vulnerable to maladaptive threat processing in the face of environmental stressors (see Gerhard et al., Reference Gerhard, Meyer and Lee2021 for review). It follows that experiences of peer victimization, particularly those that threaten peer standing via reputational damage and social manipulation, may enhance social-cognitive, socio-affective, and neurobiological sensitivity in ways that compromise mental health among adolescents (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Kliewer2013). Indeed, according to the “victim schema” model (Rosen et al., Reference Rosen, Milich and Harris2007), repeated experiences of peer victimization can elevate expectations for continued mistreatment and thus increase hypervigilance for threatening cues, particularly in ambiguous situations (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin1992; Crick & Dodge, Reference Crick and Dodge1994). Additionally, peer victimization represents a real-life example of ambiguous social threat, insofar as adolescents lack knowledge of where, when, or by whom they will be victimized, nor for how long the peer mistreatment will endure. In turn, peer victimized, compared to non-victimized, youth may show a particular sensitivity to uncertain, potential interpersonal threats, or social situations characterized by ambiguity.

Although limited attention has been given to threat sensitivity as a putative mechanism linking peer victimization to adolescent anxiety, some initial evidence supports this notion. For example, one study among a predominantly female sample of young adults identified links between self-reported frequency of past-year peer victimization at school or work and anxiety symptoms. However, this association was significant only among young adults who demonstrated elevated sensitivity to unpredictable threat, as indicated by startle eyeblink potentiation in response to potential threat (i.e., threat-of-shock; Radoman et al., Reference Radoman, Akinbo, Rospenda and Gorka2019). A recent survey study of female seventh- and eighth-grade students documented positive associations between self-reported frequency of past-month peer victimization, sensitivity to ambiguous social threats, and internalizing symptoms (Calleja & Rapee, Reference Calleja and Rapee2020). Notably, associations between peer victimization and threat sensitivity were stronger for covert (i.e., relational) forms of victimization compared to physical victimization, a pattern that was similarly reported in a study examining links between self-reported frequency of past-year peer victimization, threat appraisals, and depressive symptoms among an urban sample of adolescents in the United States (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Sullivan and Kliewer2013). Together these findings suggest positive associations between peer victimization (particularly covert) and threat sensitivity, as well as peer victimization and anxiety. However, there remain gaps in our understanding of whether: (a) social threat sensitivity mediates (i.e., accounts for) the association between peer victimization and anxiety; (b) peer victimization predicts elevated social threat sensitivity over and above other potential confounds, particularly additional forms of early life stress; (c) there are gender differences in these patterns of associations; and (d) whether results reflect self-report bias—for example, overreporting of peer victimization among youth with mental health difficulties—or would replicate across additional reporter sources (e.g., parents).

The present study

The current study aims to fill the aforementioned gaps by examining associations between peer victimization (overall, overt, and covert), sensitivity to peer-related social threat, and anxiety symptoms among adolescents. Specifically, we capitalize on multi-reporter data collected from a diverse sample of early adolescents and their parents/guardians to test four research questions and corresponding hypotheses. First, we examined whether more frequent adolescent peer victimization predicted elevated anxiety symptoms. Based on past research documenting robust positive associations between peer victimization and adolescent anxiety (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010), we expected that adolescent- and parent-report peer victimization would be positively associated with adolescent anxiety symptoms. Second, we investigated whether social threat sensitivity mediated the association between adolescent peer victimization and anxiety symptoms. Building upon past empirical and theoretical work implicating early adversity as a risk factor for aberrant threat processing (Kliewer & Sullivan, Reference Kliewer and Sullivan2008; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019) and threat sensitivity as a precursor to anxiety (Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Lissek, Rabin, McDowell, Dvir and Pine2008), we hypothesized that heightened sensitivity to potential (i.e., ambiguous) social threats would partially account for (i.e., mediate) the association between adolescent- and parent-reported peer victimization and anxiety symptoms. That is, given the developmental significance of peer relationships during adolescence, adolescents experiencing more frequent peer victimization were expected to exhibit heightened vigilance to ambiguous threats and, in turn, more severe anxiety symptoms. Third, we assessed whether covert, compared to overt, peer victimization was more strongly associated with social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms. Given preliminary evidence suggesting uniquely strong effects of covert victimization on threat appraisals (Calleja & Rapee, Reference Calleja and Rapee2020) and anxiety (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017) among adolescents, we predicted that pathways from peer victimization to anxiety via social threat sensitivity would be stronger for both adolescent- and parent-reported covert, compared to overt, peer victimization. Finally, we examined whether there were gender differences in the effects of peer victimization on social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms. Although adolescent girls are more susceptible to anxiety (Lewinsohn et al., Reference Lewinsohn, Gotlib, Lewinsohn, Seeley and Allen1998), prior studies on other forms of adversity do not support gender differences in threat sensitivity (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Sheridan, Gold, Duys, Lambert, Peverill, Heleniak, Shechner, Wojcieszak and Pine2016; Stenson et al., Reference Stenson, Nugent, van Rooij, Minton, Compton, Hinrichs and Jovanovic2021); as such, we did not expect gender to moderate pathways from peer victimization to anxiety via social threat sensitivity.

Method

Participants

A total of 197 parent–child dyads from the Metro Detroit area participated in the current study. Adolescents were all between the ages of 10–14 (M age = 12.02, SD age = 1.45; 46% female) and were racially/ethnically diverse, with 45% identifying as White, 31% Black/African American, 8% Multiethnic/Biracial, 6% Latinx, 6% South Asian, and 4% identifying as other ethnicities. Parents/guardians were between the ages of 27 and 60 (M age = 41.46, SD age = 6.05; 90% mothers; 9% fathers; 1% legal guardians) with 48% White, 33% Black/African American, 6% Latinx, 6% South Asian, and 8% identifying as other ethnicities. Parent reports indicated variability in socioeconomic status, with 17% reporting an annual household income of $150,000 or more, 24% between $100,000 and $149,999, 11% between $75,000 and $99,000, 24% between $50,000 and $74,999, 15% between $25,000 and $49,000, and 9% with $24,999 or less (1% did not report).

Procedure

Participants were recruited via online advertising (e.g., social media) and correspondence with local schools and community organizations. All data were collected via Qualtrics survey software between May 2020 and May 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Parents and their 10–14-year-olds living in the Metro Detroit area were eligible for participation. After providing consent and completing a brief online survey, parents were provided with an online survey link for their child. After both the parent and child completed their surveys, they received $20 ($5 for the parent, $15 for the adolescent) in e-gift card compensation. Given the heightened risk of fraudulent responses (e.g., bots) or inattentive humans when using online surveys, we took several recommended measures to screen responses, including use of bot detection (e.g., reCAPTCHA), attention checks, restrictions on multiple responses (i.e., ballot box stuffing), and screening of IP addresses for location within Metro Detroit (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Litovsky and Friedman-Wheeler2012; Yarrish et al., Reference Yarrish, Groshon, Mitchell, Applebaum, Klock, Winternitz and Friedman-Wheeler2019). All procedures were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Adolescent-reported peer victimization

Adolescents’ self-reported past-year peer victimization was measured using the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (R-PEQ; De Los Reyes & Prinstein (Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004)). The R-PEQ is a 9-item scale that assesses overt (e.g., “A peer hit, kicked, or pushed me in a mean way”), relational (e.g., “A peer left me out of what they were doing”), and reputational (e.g., “A peer gossiped about me so that others would not like me”) peer victimization (3 items each). Participants reported their frequency of peer victimization experiences over the past year by responding to each item on a 5-point scale (1 = “Never,” 5 = “A few times a week”). For the current study, we derived an overall score of past-year adolescent-reported peer victimization (i.e., average of nine items; α = .88) as well as two subscale scores to distinguish between covert peer victimization (i.e., average of six relational and reputational items α = .84) and overt peer victimization (i.e., average of three overt items α = .87; Tarlow & La Greca, Reference Tarlow and La Greca2021). We chose to rely on the R-PEQ given its strong psychometric properties (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004), its relatively brief length, and its inclusion of items capturing both covert and overt forms of peer victimization—victimization subtypes which have been shown to differentially predict anxiety (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017).

Parent-reported peer victimization

Parents rated their adolescents’ past-year peer victimization experiences using the same measure (i.e., R-PEQ; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004). Items were adapted to ask parents about their child’s experiences (e.g., “A kid hit, kicked, or pushed my child in a mean way”). The nine items (α = .81) were averaged to create an overall score of past-year parent-reported peer victimization, and two subscale scores were calculated to distinguish between covert (α = .83) and overt (α = .64) peer victimization.

Social threat sensitivity

Adolescents’ sensitivity to peer-related social threats was measured using a vignette-based assessment adapted from prior work (Reuman et al., Reference Reuman, Jacoby, Fabricant, Herring and Abramowitz2015) to reflect developmentally relevant hypothetical peer scenarios (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Sullivan, Kliewer, Allison, Erwin, Meyer and Esposito2006). The vignettes are described in the supplementary material. Participants were presented with two different social scenarios involving an ambiguous social threat (e.g., seeing a group of peers whispering when you walk into the room). Participants were instructed to imagine that these situations actually happened to them and think about how they would feel. Audio recorded narrations accompanied the text for each scenario, and participants used a 5-point scale to rate how scary the situation seemed to them (1 = “Not at all scary,” 5 = “Extremely scary”) and how anxious or worried they would feel in this situation (1 = “Not at all anxious,” 5 = “Extremely anxious”). These two items were averaged across the two ambiguous scenarios (i.e., four items total) to create an overall indicator of threat sensitivity (α = .86).

Anxiety

Adolescent anxiety was assessed using the 41-item Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) measure (Birmaher et al., Reference Birmaher, Brent, Chiappetta, Bridge, Monga and Baugher1999). Sample items included “I feel nervous with people I don’t know well” and “I worry about things that have already happened.” Each item was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (“Not true or hardly ever true”) to 2 (“Very true or often true”). Scores were summed to yield an overall indicator of anxiety (α = .95), where a total score greater than or equal to 25 may indicate the presence of an anxiety disorder.

Adverse experiences

To account for the potential confounding effects of early adverse experiences (i.e., separate from past-year peer victimization), adolescents were asked to report whether they had experienced a range of adverse experiences using a “Yes” or “No” response scale. Adverse experiences were taken from the 14 screening items in the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-5 (Kaplow et al., Reference Kaplow, Rolon-Arroyo, Layne, Rooney, Oosterhoff, Hill, Steinberg, Lotterman, Gallagher and Pynoos2020; Pynoos & Steinberg, Reference Pynoos and Steinberg2014; Rolon-Arroyo et al., Reference Rolon-Arroyo, Oosterhoff, Layne, Steinberg, Pynoos and Kaplow2020). Questions captured experiences of witnessing community or school violence, familial aggression, and parental neglect or separation. Sample items included “Did anyone in your family ever punish you unfairly, keep telling you that you are no good, keep yelling at you, or keep threatening to leave you or send you away?” and “Did you ever see a bad fight or shooting in your neighborhood, like between gangs? Or have you seen someone mugged, robbed, stabbed or killed in your neighborhood?”. Each participant’s “Yes” responses across the 14 items were summed to capture their total number of adverse experiences (M = .83, SD = 1.45).

Demographic covariates

Adolescents reported their gender and race/ethnicity, and parents reported their annual household income using a 6-point scale where 1 = $24,999 or less and 6 = $150,000 or more (M = 3.78, SD = 1.58). For the analyses, gender was coded such that 1 = female and 0 = male or other (3 adolescents identified as non-binary or “other”). Race/ethnicity was dummy coded into two variables (Black/African American and Other Ethnicity), where White adolescents, as the largest racial/ethnic group in the sample, served as the reference group.

Analytic plan

First, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were calculated to examine associations between the main variables of interest. Then, regression analyses were conducted to determine whether self-reported and parent-reported adolescent peer victimization were associated with elevated anxiety symptoms after controlling for adolescent gender, ethnicity, household income, and adverse experiences. Finally, indirect effect models using the PROCESS macro with 5,000 bootstraps (Hayes, Reference Hayes2018) were estimated to determine whether associations between peer victimization and anxiety symptoms were partially explained by elevated social threat sensitivity. These models were first estimated using the overall indicators of adolescent- and parent-reported peer victimization and then re-estimated using separate indicators of covert and overt peer victimizationFootnote 1 . We also examined potential gender differences in these models by testing for moderated mediation.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

As seen in Table 1, there were significant positive associations between overall peer victimization (adolescent- and parent-reported), social threat sensitivity, and anxiety symptoms. Adolescent- and parent- reported peer victimization, as well as their subscales, were also moderately correlated. Approximately 40% of the sample scored higher than the clinical cutoff value of 25 for anxiety.

Table 1. Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations for main study variables

Note.

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Research question 1: does peer victimization predict anxiety symptoms?

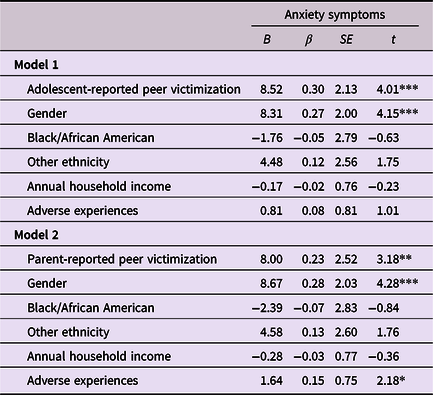

Table 2 presents the results from the regression models examining adolescent-reported peer victimization (Model 1) and parent-reported peer victimization (Model 2) as predictors of adolescent anxiety symptoms after controlling for adolescent gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (i.e., annual household income), and adverse experiences. Both adolescent- and parent-reported peer victimization predicted elevated anxiety symptoms after accounting for potentially confounding demographic and psychosocial factors. For every one standard deviation increase in past-year adolescent-reported peer victimization, adolescents displayed approximately a one-third of a standard deviation increase in anxiety symptoms. For every one standard deviation increase in past-year parent-reported peer victimization, adolescents had an approximately one-quarter of a standard deviation increase in anxiety symptoms.

Table 2. Linear regression analyses examining the effect of peer victimization on anxiety symptoms after controlling for adolescent demographic and psychosocial variables

Note. B = unstandardized estimate. β = standardized estimate. SE = standard error.

* p < .05,

** p < .01,

*** p < .001.

Research question 2: does social threat sensitivity mediate the association between peer victimization and anxiety symptoms?

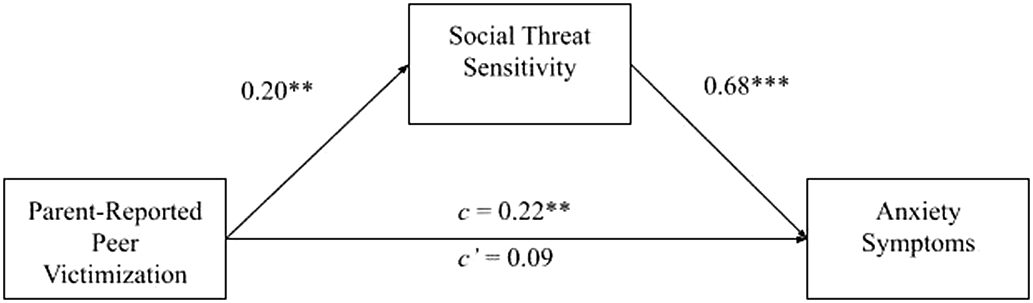

Results from the indirect effect models examining adolescent-reported and parent-reported peer victimization as predictors of anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. As seen in Figure 1, after controlling for the demographic and psychosocial covariates, there was a significant indirect effect of adolescent-reported peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity (completely standardized indirect effect = .16, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = .05–.26). These results also replicated when examining parent-reported peer victimization, rather than adolescent-reported peer victimization, as the main predictor. Specifically, as seen in Figure 2, after controlling for potential demographic and psychosocial confounds, there was a significant indirect effect of parent-reported peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity (completely standardized indirect effect = .14, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = .05–.23).

Figure 1. Significant indirect effect of adolescent-reported peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity. Note. Path estimates indicate standardized effects after controlling for adolescent gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (household income), and adverse experiences. c = total effect; c’ = direct effect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 2. Significant indirect effect of parent-reported peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity. Note. Path estimates indicate standardized effects after controlling for adolescent gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (household income), and adverse experiences. c = total effect; c’ = direct effect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Research question 3: does covert, compared to overt, peer victimization more strongly predict social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms?

To determine whether there were differential effects of covert versus overt peer victimization on social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms, four additional indirect effect models were estimated (two for adolescent-report and two for parent-report). In the models examining adolescent- and parent-reported covert peer victimization as the predictors, we controlled for participants’ levels of adolescent- and parent-reported overt peer victimization, and vice versa. We also controlled for the potentially confounding demographic and psychosocial variables described above. As seen in Figure 3, there was a significant indirect effect from covert adolescent-reported peer victimization to anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity, even after controlling for overt victimization (completely standardized indirect effect = .15, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = .01–.30). This pattern also replicated when examining parent-reported covert victimization as the predictor (completely standardized indirect effect = .13, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = .01–.24). However, as seen in Figure 4, there was a nonsignificant indirect effect from adolescent-reported overt peer victimization to anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity after controlling for adolescent-reported covert victimization (completely standardized indirect effect = .02, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = −.15 to .17). That is, overt victimization was unrelated to social threat sensitivity and anxiety after accounting for adolescents’ experiences of covert victimization. This pattern also replicated when examining parent-reported overt victimization as the predictor (completely standardized indirect effect = .03, 95% bootstrap confidence interval = −.08 to .13).

Figure 3. Significant indirect effect of adolescent-reported covert peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity. Note. Path estimates indicate standardized effects after controlling for overt peer victimization, adolescent gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (household income), and adverse experiences. c = total effect; c’ = direct effect. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Figure 4. Nonsignificant indirect effect of adolescent-reported overt peer victimization on anxiety symptoms via social threat sensitivity. Note. Path estimates indicate standardized effects after controlling for covert peer victimization, adolescent gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (household income), and adverse experiences. c = total effect; c’ = direct effect. ns = not statistically significant, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Research question 4: do the effects of peer victimization on social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms vary by gender?

In a final set of models, we conducted moderated mediation analyses to determine whether peer victimization (adolescent- or parent-reported) interacted with adolescent gender to predict social threat sensitivity and/or anxiety symptoms. Results from the moderated mediation models indicated non-significant gender differences in the effect of peer victimization on threat sensitivity (self-report model: b = 0.00, p = .989; parent-report model: b = 0.08, p = .768) or anxiety symptoms (self-report model: b = −2.84, p = .292; parent-report model: b = −3.66, p = .284). There was also no evidence of gender moderation for the models examining victimization subtypes (i.e., covert and overt). Follow-up exploratory analyses also indicated that there were no significant gender differences in the effect of social threat sensitivity on adolescent anxiety symptoms (b = −1.55, p = .373).

Discussion

Leveraging multi-reporter data, the current study identified positive associations between peer victimization experiences, social threat sensitivity, and anxiety symptoms among a diverse sample of early adolescents. Additionally, there was evidence for significant indirect effects from adolescent- and parent-reported peer victimization to adolescent anxiety via social threat sensitivity, and supplemental analyses point to the unique effects of covert (i.e., relational; reputational) as compared to overt (i.e., physical; verbal) forms of peer victimization. Further, these associations were robust to potentially confounding demographic (i.e., gender, ethnicity, income) and psychosocial (i.e., adverse experiences) factors. Given that aberrant threat sensitivity is linked to the pathophysiology of anxiety and is tractable to interventions (Grillon, Reference Grillon2008; Grillon et al., Reference Grillon, Lissek, Rabin, McDowell, Dvir and Pine2008; Shechner et al., Reference Shechner, Britton, Pérez-Edgar, Bar-Haim, Ernst, Fox, Leibenluft and Pine2012), these data suggest that sensitivity to peer-related social threats may be a target for interventions among peer victimized adolescents to reduce risk of anxiety.

Consistent with our first hypothesis, there was a significant association between adolescent peer victimization (both adolescent- and parent-reported) and anxiety. That is, adolescents who were more frequently bullied by peers over the past year also exhibited more severe anxiety symptoms. Importantly, results were consistent across both adolescent and parent reports of peer victimization, reducing concerns about reporter bias and indicating the robustness of the documented patterns (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Reference De Los Reyes and Prinstein2004). This is notable insofar as most previous studies documenting associations between peer victimization and adolescent anxiety have relied on self-reports (see Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021; Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie and Telch2010 for meta-analyses). For example, in a recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies examining the association between peer victimization and internalizing problems (Christina et al., Reference Christina, Magson, Kakar and Rapee2021), approximately 70% of identified studies used a self-report measure of peer victimization, and the remaining 30% used peer nominations (14%) or cross-informant summary scores (e.g., pooling parent and child reports; 15%). Although the meta-analysis did not include cross-sectional studies, these findings suggest a general paucity of multi-informant studies on peer victimization and adolescent anxiety. We also found that associations between both adolescent- and parent-reported peer victimization and anxiety emerged over and above the effects of other potentially influential confounding variables, including participant demographic (i.e., gender, ethnicity) and psychosocial (i.e., adverse early experiences) factors. These findings further underscore peer victimization as a unique and developmentally salient form of stress during the adolescent years.

The most novel finding from the current study was that heightened social threat sensitivity partially mediated the association between peer victimization and adolescent anxiety. Specifically, adolescents who experienced more frequent peer harassment over the prior year were more likely to interpret danger in ambiguous peer-related social situations which, in turn, was related to higher levels of anxiety. This result provides preliminary support for a mechanistic role of social threat sensitivity in explaining pathways from peer victimization to adolescent anxiety. Follow-up analyses also implicated a unique effect of covert, but not overt, victimization on social threat sensitivity and anxiety. Such findings suggest that during adolescence, being the target of social manipulation, exclusion, and reputational damage may be particularly distressing, insofar as they threaten adolescents’ fundamental developmental need for peer connection and approval. Indeed, a 2017 meta-analysis indicated that indirect forms of peer victimization, compared to direct verbal or physical harassment, were more strongly related to internalizing symptoms (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017), and other work has suggested that relational, compared to overt, victimization has stronger effects on adolescent social-cognitive processing (Hoglund & Leadbeater, Reference Hoglund and Leadbeater2007). These data also fit with prior work linking other forms of early adversity, such as violence exposure or being the target of familial abuse, to heightened neural and physiological responses to threatening stimuli (Marusak et al., Reference Marusak, Hehr, Bhogal, Peters, Iadipaolo and Rabinak2021; van Rooij et al., Reference van Rooij, Smith, Stenson, Ely, Yang, Tottenham, Stevens and Jovanovic2020). While elevated sensitivity to potential threats may be adaptive in the short term by promoting survival, these psychobiological changes may have long-term negative consequences for mental health. In particular, anxiety and other fear-based disorders (e.g., posttraumatic stress disorder) are consistently linked to heightened neural sensitivity to potential threats (Dvir et al., Reference Dvir, Horovitz, Aderka and Shechner2019; Suarez-Jimenez et al., Reference Suarez-Jimenez, Albajes-Eizagirre, Lazarov, Zhu, Harrison, Radua, Neria and Fullana2020), and altered threat sensitivity has long been implicated in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety (e.g., Britton et al., Reference Britton, Lissek, Grillon, Norcross and Pine2011). Together, our results extend prior research by showing that peer victimization is a salient exposure that may increase the risk of anxiety via heightened social threat sensitivity, above and beyond other forms of adversity.

The current study had several limitations. First, although theoretically motivated, the mediation analyses were based on cross-sectional data and preclude any conclusions about directionality or causality. Based on prior theory and empirical evidence (e.g., Calleja & Rapee, Reference Calleja and Rapee2020; Jovanovic et al., Reference Jovanovic, Smith, Kamkwalala, Poole, Samples, Norrholm, Ressler and Bradley2011; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, DeCross, Jovanovic and Tottenham2019), it was hypothesized that frequent experiences of peer victimization lower adolescents’ thresholds for interpreting threat in ambiguous social situations, and such changes in threat processing subsequently contribute to the development of anxiety. However, it is additionally or alternatively possible that anxiety and threat sensitivity precede victimization, such that adolescents who exhibit hypervigilance and high levels of worry in social situations are more likely to perceive peer mistreatment. Also, the measures of social threat sensitivity and anxiety symptoms were highly correlated. Thus, it will be important for future longitudinal studies to replicate the current findings and investigate the potentially transactional long-term links between peer victimization, threat processing, and adolescent anxiety. Second, although the incorporation of both adolescent and parent reports of peer victimization was a strength, the study was limited by relying on self-reported threat sensitivity. Further, in order to minimize survey length and participant burden, we only presented two hypothetical vignettes that captured situations involving ambiguous threat in peer-related social scenarios. Assessments that include additional vignettes and vary the degree or type of uncertainty presented (e.g., implicit vs. explicit; Reuman et al., Reference Reuman, Jacoby, Fabricant, Herring and Abramowitz2015) would offer a more thorough method for evaluating self-reported social threat sensitivity. Physiological assessments of threat processing could also provide further insights into well-characterized objective markers of anxiety risk that may provide a better understanding of the underlying neurodevelopmental mechanisms (e.g., exaggerated corticolimbic response to potential threats; Marusak et al., Reference Marusak, Zundel, Brown, Rabinak and Thomason2017). However, it is worth noting that self-reported measures of threat sensitivity have been associated with physiological threat reactivity in past research (e.g., startle potentiation; Vaidyanathan et al., Reference Vaidyanathan, Patrick and Bernat2009). Third, we did not collect information about adolescents’ depressive symptoms, which can exhibit high comorbidity with anxiety. It would be important for future studies to replicate the current findings while accounting for youth’s depressive symptoms. Fourth, both adolescent-reported and parent-reported peer victimization were reported at low frequencies, as is quite typical among community samples of adolescents (e.g., Saint-Georges & Vaillancourt, Reference Saint-Georges and Vaillancourt2020). Although even isolated or infrequent experiences of peer victimization can increase risk for psychological distress (Nishina & Juvonen, Reference Nishina and Juvonen2005), chronically victimized youth typically show the most severe mental health outcomes (Sheppard et al., Reference Sheppard, Giletta and Prinstein2019); in turn, it is possible that the low frequencies, particularly for overt forms of peer victimization, attenuated associations with threat sensitivity or anxiety. Future studies that intentionally over-sample adolescents experiencing more frequent peer victimization would allow for testing the robustness of our current findings among those who are chronically bullied by peers. Finally, the current data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, and the potential lack of generalizability of the findings should also be considered. For example, approximately 40% of the sample met the screening cutoff for potential presence of an anxiety disorder, which may in part have reflected context-specific worries or concerns about the pandemic.

Implications

Whereas many anti-bullying interventions exist to reduce or prevent bullying at the group level, few exist to mitigate the emotional impact of peer victimization on individual targets. If reactivity to ambiguous social threat underlies associations between peer victimization and anxiety, a pattern that is preliminarily supported by the current findings, threat sensitivity could function as an important diagnostic tool for both prevention and treatment. Indeed, physiological threat responses are considered a robust translational model of anxiety risk that are relevant to interventions, such as cognitive bias modification, mindfulness-based interventions (Papenfuss et al., Reference Papenfuss, Lommen, Grillon, Balderston and Ostafin2021), and cognitive behavioral therapy (Grillon & Ernst, Reference Grillon and Ernst2020). However, few studies have utilized threat sensitivity as a potentially useful phenotypic readout of anxiety risk in developing populations. Future studies should evaluate social threat sensitivity as a potential marker of anxiety risk among peer victimized adolescents and guide the design of developmentally sensitive cognitive behavioral intervention approaches.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422001018

Acknowledgments

We thank Hira Haider and Anna Sampson for their assistance with data collection for this study. Thank you also to the schools and community organizations that shared information about our study as well as the parents and youth who participated.

Funding statement

Dr. Marusak is supported by NIH grant K01MH119241 (to HM). The research was supported by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Wayne State University School of Medicine.

Conflicts of interest

None.