Introduction

An enduring issue in the mental health field is identifying mechanisms and developmental processes that explain how childhood characteristics progress to maladaptive adolescent and adult forms. Because of the research attention devoted to it, behavioral inhibition (BI) is currently our best example of a temperamental trait that biases reactions to later stressors in a way that can result in maladaptive behavioral patterns. In general, temperament reflects individual differences underlying affective reactivity and regulation (Goldsmith et al., Reference Goldsmith, Buss, Plomin, Rothbart, Thomas, Chess, Hinde and McCall1987). More specifically, research on BI, defined as reticence or withdrawal in the face of novelty or threat, illustrates the complexity that challenges developmental psychopathology research. Summarizing a large literature, we observe that BI is conceptualized as a category or type (e.g., Kagan et al., Reference Kagan, Reznick, Clarke, Snidman and Garcia-Coll1984) or as a dimension (Trull & Durrett, Reference Trull and Durrett2005), with more evidence favoring dimensions (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Holland and Kuppens2012). With the dimensional approach, BI to social vs. nonsocial stimuli is usefully distinguished (Dyson et al., Reference Dyson, Klein, Olino, Dougherty and Durbin2011), as is BI to threatening vs. everyday stimuli (Buss, Reference Buss2011). Individual differences in BI are moderately but not highly stable across major developmental transitions (Pfeifer et al., Reference Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson and Rickman2002). Variation in BI predicts later social anxiety (SA; Pérez-Edgar & Guyer, Reference Pérez-Edgar and Guyer2014), and crucially, chronically high BI predicts susceptibility to SA (Hirshfeld et al., Reference Hirshfeld, Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc, Faraone, Snidman, Reznick and Kagan1992; Poole et al., Reference Poole, Cunningham, McHolm and Schmidt2020). Indeed, anxiety disorders as a broader group were the sixth leading cause of disability worldwide in 2010. The burden is disproportionately borne by 15–34 year-olds (Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Vos, Scott, Ferrari and Whiteford2014), where 8.6% of adolescents and 13% of adults meet diagnostic criteria for Social Anxiety Disorder (SA; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Avenevoli, Costello, Georgiades, Greif Green, Gruber, He, Koretz, McLaughlin, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Merikangas2012). However, investigation of links between BI and SA across adolescence, attending to factors which contribute to genetic and experiential factors, is limited. Social factors such as parenting style and peer relationships—which we analyze in this paper—can moderate BI’s association with later anxiety (Frenkel et al., Reference Frenkel, Fox, Pine, Walker, Degnan and Chronis-Tuscano2015). Thus, the investigation of how BI sometimes predisposes for the emergence of SA has assumed a prototypic role. BI provides the prototype for future biobehavioral investigations that involve other temperament dimensions, complex genetic and environmental interplay that continues over development, and psychiatric outcomes, a point also highlighted by Pérez-Edgar and Fox (Perez-Edgar & Fox, Reference Perez-Edgar and Fox2018). Here, we study the full range of SA, from very low to clinically significant levels, during a period when it can crucially impact adolescent functioning.

Overview of the phenotypic questions

Here, we conceptualize our focal predictor, BI, as a dimension rather than as a category, and our analyses all embrace a dimensional perspective. We are among many theorists who have treated the measurement of BI empirically (Goldsmith & Lemery, Reference Goldsmith and Lemery2000; Pfeifer et al., Reference Pfeifer, Goldsmith, Davidson and Rickman2002). We will not reiterate the complexities of the types vs. dimensions debate, which also pertains to personality traits more generally and to dimensional views of psychopathology, such as the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC; Cuthbert & Insel, Reference Cuthbert and Insel2013) and the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Waszczuk, Krueger, Forbes, Watson, Clark, Achenbach, Althoff, Ivanova, Michael Bagby, Brown, Carpenter, Caspi, Moffitt, Eaton, Forbush, Goldberg, Hasin, Hyman and Zimmerman2017). This paper considers phenotypic and genotypic issues relating to BI and its developmental association with SA in the understudied developmental period from middle childhood into adolescence.

In what senses does BI predict SA?

The extant literature affirmatively answers the basic question of whether BI predicts SA. One meta-analysis shows a greater than seven-fold increase in SA specifically for BI versus non-BI individuals (Clauss & Blackford, Reference Clauss and Blackford2012). In another study with a different sample but similar measures, we showed that a multisource measure of shyness at age 3 predicted a broader anxiety measure at 8 years (Volbrecht & Goldsmith, Reference Volbrecht and Goldsmith2010). As we consider this issue, embedded questions become apparent. A key issue is whether single instance assessment of BI is a theoretically justified predictor in analyses of BI-to-SA associations. Although associations of single instance BI assessment might be associated with later anxiety, most theorizing about BI treats it as a trait-like dimension, so that mean levels of BI, when high, imply that chronic BI is likely. Although a single assessment of BI might sample a trait-like dimension, state effects might also contaminate or even dominate the assessment. Thus, incorporating evidence of both mean levels across time and multimodal assessment directly into the BI predictor seems a preferable strategy.

Continuity and directionality of BI-to-SA predictions

Predicting SA from earlier BI requires analysis of the continuity of both BI and SA over the period of prediction as well as an understanding of the directionality between these associations. Thus, an underlying model of longitudinal continuity and change must be adopted, at least implicitly. The most common and simplest analysis of continuity for our context is one that uses a cross-lagged panel approach, which provides information on continuity of both BI and SA, along with longitudinal and concurrent prediction of BI-to-SA and SA-to-BI: Does BI predict SA, or might SA predict future BI? Here, the prediction of BI for SA could be viewed as consistent with the vulnerability model, whereas the possible prediction of SA from BI would fit the complication or scar model (Tackett, Reference Tackett2006), which has mainly been studied for adult depression and substance use and not in the childhood internalizing domain.

Temperament-psychopathology associations of BI-to-SA

In addition to models of continuity, another deeper issue is the models for temperament-psychopathology associations, which largely derive from the personality-psychopathology models. Three primary hypotheses depict relations between temperament and psychopathology (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Watson and Mineka1994; Tackett, Reference Tackett2006). Vulnerability models posit that certain types of temperament predispose individuals to psychopathology. Complication or scar models raise the possibility of the opposite direction-of-effect, such that emerging psychopathology changes temperament (Bianconcini & Bollen, Reference Bianconcini and Bollen2018). Finally, spectrum models suggest that corresponding aspects of temperament and psychopathology lie along the same continuum and share underlying causal processes. The spectrum model has garnered the most support (Markon, Reference Markon2019) although the models are not mutually exclusive, and the other models may explain relations between specific traits and disorders (Gartstein et al., Reference Gartstein, Putnam and Rothbart2012).

Specificity of behavioral inhibition and SA associations

Another question addresses the specificity of the BI-to-SA prediction: does BI predict SA specifically, or is it a more general risk factor for anxiety or for other symptom dimensions such as depression or externalizing behaviors? The specificity hypothesis is risky, as temperamental traits often predict in a transdiagnostic manner (Hankin et al., Reference Hankin, Davis, Snyder, Young, Glynn and Sandman2017; Kostyrka-Allchorne et al., Reference Kostyrka-Allchorne, Wass and Sonuga-Barke2020; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Tang, Bowers, Miller, Buzzell, Smith, Seddio, Henderson and Fox2021). Furthermore, SA is associated with increased risk for other psychiatric diagnoses, particularly mood, other anxiety, and substance use disorders. SA predicts increased severity of comorbid depression (Beesdo et al., Reference Beesdo, Bittner, Pine, Stein, Höfler, Lieb and Wittchen2007; Fehm et al., Reference Fehm, Beesdo, Jacobi and Fiedler2008); 87.8% of adults with SA had additional psychiatric diagnoses during a 12-month period (Fehm et al., Reference Fehm, Beesdo, Jacobi and Fiedler2008). When this striking comorbidity is considered alongside the significant impairment that accompanies subdiagnostic threshold SA, the overall impact of SA is tremendous (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK), 2013). However, a recent, questionnaire-based twin study supported the specificity hypothesis by showing that retrospectively reported childhood BI specifically predicted adolescent SA (and not other internalizing disorders); BI shared both genetic (20%) and environmental (16%) variance with adolescent anxiety (Bourdon et al., Reference Bourdon, Savage, Verhulst, Carney, Brotman, Pine, Leibenluft, Roberson-Nay and Hettema2019), a finding that foreshadows one of our results.

Moderation of the effects of BI on SA

We can conceptualize any “third variable” (e.g., sex of child) that moderates the prediction of SA from BI as a source of heterogeneity that alters, by either weakening or strengthening, BI-to-SA links. Rather than deriving potential moderators from a specific theoretical framework, we conducted a literature review from which seven possible sources of heterogeneity were identified: sex of child, over-protective parenting, peer victimization, socioeconomic status of the family, family stress, pubertal timing, and parent internalizing psychopathology. These seven variables vary in nature. Over-protective parenting and peer victimization are specific, proximal measures of experience within and outside the family environment, respectively. Family stress and SES are more general, more distal, and likely correlated variables that are often examined in the literature. Child’s pubertal timing and mothers’ and fathers’ internalizing psychopathology likely reflect both genetic and experiential effects. However, none of these potential moderators are unambiguously biological/genetic or environmental/experiential in nature. What findings in the literature empirically justify inclusion of these potential moderators in our analyses?

Sex of child

Sex differences in the development of SA are established, with women having both greater lifetime prevalence and severity of SA than men (Asher et al., Reference Asher, Asnaani and Aderka2017). These differences in prevalence are apparent both during adolescence (Merikangas et al., Reference Merikangas, He, Burstein, Swanson, Avenevoli, Cui, Benjet, Georgiades and Swendsen2010) and adulthood (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Schneier, Heimberg, Princisvalle, Liebowitz, Wang and Blanco2012), and in both community samples (Beesdo et al., Reference Beesdo, Bittner, Pine, Stein, Höfler, Lieb and Wittchen2007) and clinical samples (Yonkers et al., Reference Yonkers, Bruce, Dyck and Keller2003). Similarly, BI research, including our own, indicates higher BI and anxiety for females in late childhood and adolescence (Gagne et al., Reference Gagne, Miller and Goldsmith2013; Janson & Mathiesen, Reference Janson and Mathiesen2008; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Durbin, Klein, Hayden and Dyson2013). The association between BI and SA is stronger for females than males in childhood and adolescence (Hayward et al., Reference Hayward, Wilson, Lagle, Kraemer, Killen and Taylor2008; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Snidman and Kagan1999; Tsui et al., Reference Tsui, Lahat and Schmidt2017). Importantly, for analyses identifying the moderating effects of risk factors on links between BI and SA, risk factors for development of SA may also differ by sex. For instance, parent conflict was a risk factor for girls, while absence of an adult confidant was a risk factor for boys (DeWit et al., Reference DeWit, Chandler-Coutts, Offord, King, McDougall, Specht and Stewart2005). Thus, sex of child was incorporated into the models.

Parenting and the family environment

Parenting and family dynamics play an important role in child development. Specifically, overprotective parenting can have adverse effects on emerging patterns of psychopathology, particularly relating to SA (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Wood and Weisz2007; Spokas & Heimberg, Reference Spokas and Heimberg2009). Overprotective parenting includes aspects of parental behaviors that are both warm and controlling, yet excessive in the context of the child’s developmental stage; parents do not allow their child the space to engage in appropriate emotional or regulatory behaviors on their own (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Henderson, Fox and Rubin2008, Reference Degnan, Almas and Fox2010; Kiel & Maack, Reference Kiel and Maack2012).

The literature provides strong evidence that parenting stress is particularly salient in children’s emerging psychopathology. Worried or anxious parents may be more likely to exhibit overprotective parenting, which in turn may increase risk for child anxiety symptoms and disorders; however, findings about this association are mixed and focus predominantly on maternal parenting (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Hall and Kiel2021; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Whaley and Sigman2004). Anxious mothers may be hypervigilant to perceived threats in their child’s environment and may seek to reduce their own anxious distress by exerting control over their child’s behaviors or environment (Eysenck, Reference Eysenck2013; Lindhout et al., Reference Lindhout, Markus, Hoogendijk, Borst, Maingay, Spinhoven, van Dyck and Boer2006; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Beidel, Roberson-Nay and Tervo2003).

As a consequence of the issues just discussed, children of overprotective parents may not develop the skills essential for healthy coping or resilience (Van Petegem et al., Reference Van Petegem, Albert Sznitman, Darwiche and Zimmermann2021). In early childhood, maternal overprotective or controlling parenting is associated with increased child fear at 2 years of age (Kiel & Maack, Reference Kiel and Maack2012), child inhibition at 4 years of age (Rubin et al., Reference Rubin, Burgess and Hastings2002), and higher inhibition in middle school (Degnan et al., Reference Degnan, Henderson, Fox and Rubin2008). Further, mothers’ overprotective parenting moderates relations between shyness and internalizing and poor social interactions in kindergarteners (Coplan et al., Reference Coplan, Arbeau and Armer2008). Thus, we anticipate that mothers’ overprotective parenting will enhance associations between child early BI and emerging SA.

Parent internalizing psychopathology & wellbeing

Elevations in parental negative affect and lower levels of positive affect associated with internalizing diagnoses may shape risk for BI during childhood. Although diagnostic assessments of internalizing psychopathology tend to capture high negative affect effectively, they often do not accurately reflect low positive affect (Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988). Thus, assessing how both increased negative affect (e.g., presence of anxiety disorder) and decreased positive affect (e.g., lower wellbeing score) among parents may influence trajectories of child behavioral inhibition is essential. Specifically, in a sample of inhibited preschool aged children, elevations in parental negative affect were associated with subsequent emergence of clinically significant child anxiety symptoms (Bayer et al., Reference Bayer, Prendergast, Brown, Bretherton, Hiscock, Nelson-Lowe, Gilbertson, Noone, Bischof and Beechey2021). Although parental depression and panic disorder relate individually to increased risk for childhood BI, the combination of parental depression and panic disorder is associated with an even larger increase in risk for BI (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Biederman, Hirshfeld-Becker, Kagan, Snidman, Friedman, Nineberg, Gallery and Faraone2000). The presence of multiple parental anxiety disorders appears to increase risk similarly. For instance, parents of BI children who also qualify for an anxiety disorder diagnosis are significantly more likely to have at least two anxiety disorders of their own (Rosenbaum et al., Reference Rosenbaum, Biederman, Bolduc, Hirshfeld, Faraone and Kagan1992). Few studies emphasize the possible differential effects of father and mother internalizing problems, as we do in this paper.

Socioeconomic status of the family

Despite being a more distal factor than specific parenting behaviors, the impact of socioeconomic resources (SES) may increase risk for developing anxiety throughout childhood. In a study of 9700 Norwegian children aged 10–13, SA and other mental health problems were higher in a low SES group compared with a higher SES group, particularly when children were asked to perform in front of others (Karlsen et al., Reference Karlsen, Clench-Aas, Van Roy and Raanaas2014). Here, we operationalize SES using two indicators of parents’ education and occupation. Education, rather than income, is an appropriate proxy variable for SES in studies that address family issues relating to child and adolescent mental health (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Costello, Leblanc, Sampson and Kessler2012). Using SES in the analysis also helps us connect our findings with other studies.

Peer victimization

Peer victimization is an experience that may complicate associations between BI and SA. Peer victimization refers to the repeated experience of being a target of intentionally aggressive behavior by peers (Olweus, Reference Olweus2001). Behaviorally inhibited youth experience heightened rates of peer victimization and ostracism (Affrunti et al., Reference Affrunti, Geronimi and Woodruff-Borden2014; Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard2001; Hanish & Guerra, Reference Hanish and Guerra2004; Kochenderfer-Ladd, Reference Kochenderfer-Ladd2003; Newcomb et al., Reference Newcomb, Bukowski and Pattee1993; Sugimura & Rudolph, Reference Sugimura and Rudolph2012), and problems with peers during childhood and adolescence (Booth-Laforce et al., Reference Booth-Laforce, Oh, Kennedy, Rubin, Rose-Krasnor and Laursen2012; Hasenfratz et al., Reference Hasenfratz, Benish-Weisman, Steinberg and Knafo-Noam2015). Peer victimization experience in youth is associated with higher rates of SA (Arseneault et al., Reference Arseneault, Milne, Taylor, Adams, Delgado, Caspi and Moffitt2008), as well as other internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Reijntjes et al., Reference Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, Boelen, Van der Schoot and Telch2011). These adverse outcomes are not confined to childhood and adolescence; multiple studies demonstrate that the effects of peer victimization on psychopathology persist into adulthood. Given increased rates of peer victimization amongst higher BI youth, and the associations between peer victimization and SA in childhood and adolescence, including peer victimization as a potential moderator examining associations between BI and SA is strongly justified.

Pubertal timing

Limited evidence in adolescence indicates that pubertal development may have a mechanistic role in the BI–SA association. Early pubertal timing (mature pubertal status relative to age-matched youth) is associated with increased SA (Blumenthal et al., Reference Blumenthal, Leen-Feldner, Trainor, Babson and Bunaciu2009) as well as other mood and anxiety disorders in adolescence (Black & Rofey, Reference Black and Rofey2018). A study of 8–14-year-old girls found that mature pubertal status was associated with altered habituation to threat and safety cues during fear conditioning—demonstrating a dampened response to threat (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Nelson, Meyer and Hajcak2017). Although the underlying pubertal mechanism seems unclear, developmental maturation appears to play a role in fear extinction; thus, more investigation on puberty’s role in the BI-to-SA association is warranted.

Overview of the genetic considerations

Are BI and SA heritable phenotypes and do they share genetic underpinnings?

The literature based on differential similarity of different classes of genetic kin (e.g., members of MZ vs. DZ twin pairs) confirms a positive answer to this question. However, BI and SA are not highly heritable phenotypes, which means that their study should include frequently occurring experiences in conjunction with genetics. Background for the behavior-genetic analysis is provided by twin studies that have documented moderate genetic effects on variation in early BI (Cherny et al., Reference Cherny, Fulker, Corley, Plomin and DeFries1994; Matheny, Reference Matheny1989) as well as on continuity of BI through early development (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Rhee, Corley, Friedman, Hewitt and Robinson2012). We previously showed, in a sample that overlaps the one in the current analyses, that parent-rated and observational assessments of social and nonsocial fear in school-age children were genetically distinct from anger and sadness (Clifford et al., Reference Clifford, Lemery-Chalfant and Goldsmith2015). Both continuity and change in the development of BI from adolescence to adulthood were heritable in a questionnaire-based twin study (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Yamagata, Kijima, Shigemasu, Ono and Ando2007). The stability of both BI and anxiety is largely driven by genetic factors, though non-shared environmental influences play a role as well (Ellis & Rothbart, Reference Ellis and Rothbart2001; Hannigan et al., Reference Hannigan, Walaker, Waszczuk, McAdams and Eley2017). A recent twin study showed that BI specifically predicted adolescent SA (and not other internalizing disorders); BI shared both genetic (20%) and environmental (16%) variance with adolescent anxiety (Bourdon et al., Reference Bourdon, Savage, Verhulst, Carney, Brotman, Pine, Leibenluft, Roberson-Nay and Hettema2019). A two-wave twin study of late adolescents/young adults using the BIS/BAS scales demonstrated that the genetic variance in BIS scores accounted for genetic effects on both depression and generalized anxiety (measured later), whereas the genetic variance in the BAS scores predicted only depression (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Yamagata, Ritchie, Barker and Ando2021). Thus, biometric studies implicate genetic and non-shared environmental factors in the BI–SA association, but a study such as ours with a large sample size, multimodal assessment, and more than two ages studied is greatly needed to solidify our understanding.

Turning to SA, three meta-analyses (Hettema et al., Reference Hettema, Neale and Kendler2001; Moreno et al., Reference Moreno, Osório, Martin-Santos and Crippa2016; Scaini et al., Reference Scaini, Belotti and Ogliari2014) examine the heritability of SA measured in a variety of ways across a variety of clinical and non-clinical samples. Low to moderate heritability estimates are typical in this literature, which extends beyond twin studies to other kinship designs. Yet evidence for genetic effects on SA are not limited to quantitative analyses of kinship similarity data. Genome-wide association studies on anxiety more broadly (Levey et al., Reference Levey, Gelernter, Polimanti, Zhou, Cheng, Aslan, Quaden, Concato, Radhakrishnan, Bryois, Sullivan and Stein2020) and SA specifically (Stein et al., Reference Stein, Chen, Jain, Jensen, He, Heeringa, Kessler, Maihofer, Nock, Ripke, Sun, Thomas, Ursano, Smoller and Gelernter2017) are being reported. In the first GWAS study of SA, Stein et al. (Reference Stein, Chen, Jain, Jensen, He, Heeringa, Kessler, Maihofer, Nock, Ripke, Sun, Thomas, Ursano, Smoller and Gelernter2017) estimated a SNP-based heritability of 12%. (Such SNP-based heritability estimates cannot be compared directly with the kinship model-based estimates reviewed above.) Meier et al. (Reference Meier and Deckert2019) examined anxiety and stress-related phenotypes more broadly in an GWAS analysis; they estimated a SNP-based heritability of 28%. Levey et al. (Reference Levey, Gelernter, Polimanti, Zhou, Cheng, Aslan, Quaden, Concato, Radhakrishnan, Bryois, Sullivan and Stein2020), studying generalized anxiety as a dimensional trait, identified several genes to be associated with anxiety in a sample of 200,000 participants, and we expect future large-scale GWAS studies of SA more specifically from a consortium working on the issue.

In summary, multi-method evidence shows that unexplained non-genetic variance in SA remains to be accounted for by factors that we did not study here, but which may contribute to developing SA. Here, we advance genetic analyses by starting with bivariate biometric analyses that ask whether childhood BI’s effect on adolescent SA has a partially genetic basis and whether residual genetic variance remains for SA after the genetic contribution from BI is considered.

Approach to research questions

Although a link between BI and later SA is established (Eley et al., Reference Eley, McAdams, Rijsdijk, Lichtenstein, Narusyte, Reiss, Spotts, Ganiban and Neiderhiser2015; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005; Klein & Mumper, Reference Klein, Mumper, Pérez-Edgar and Fox2018; Paulus et al., Reference Paulus, Backes, Sander, Weber and von Gontard2015; Sylvester & Pine, Reference Sylvester, Pine, Pérez-Edgar and Fox2018; White et al., Reference White, Degnan, Henderson, Pérez-Edgar, Walker, Shechner, Leibenluft, Bar-Haim, Pine and Fox2017), understanding the complexities and contingencies in this link remains a challenge. We still lack a comprehensive understanding of the etiology and developmental course(s) of BI. Ambiguity about heterogeneity of BI effects on later development precludes clear answers to both etiological and developmental questions

In brief, we examine whether the anticipated prediction from BI to later dimensional SA is (1) specific to SA (relative to other internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms) and whether associations between BI and SA were unidirectional (BI-to-SA only). To test the latter, we use a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM), which also offers autoregressive paths representing continuity of BI and SA, along with their cross-prediction from middle childhood, through early adolescence, to our final assessment later in adolescence. This CLPM allows us to preliminarily examine the BI-SA and SA-BI paths that are also probed in the subsequent bivariate biometric models and multilevel models. Notably, because of recent criticisms of classic CLPM models, we followed recommendations to estimate a RI-CLPM (Berry & Willoughby, Reference Berry and Willoughby2017). With the pattern of BI-to-SA association characterized, we interrogate genetic and environmental underpinnings of association using a bivariate biometric model. Then, we screen potential moderators for their interactive effects in the BI-to-SA prediction. The moderators that pass this screen are incorporated into a final model of the predictive nexus.

Method

Overview

The data were collected over two decades in a longitudinal project. Although BI and SA figured prominently into the design, its scope included other aspects of temperament and emotionality, as well as risk and resilience factors for child and adolescent psychopathology more generally (Schmidt, Brooker, et al., Reference Schmidt, Brooker, Carroll, Gagne, Luo, Planalp, Sarkisian, Schmidt, Van Hulle, Moore, Lemery-Chalfant and Goldsmith2019; Schmidt, Lemery-Chalfant, et al., Reference Schmidt, Lemery-Chalfant and Goldsmith2019). The project was funded by different mechanisms, each with their differing priorities and differing resources for follow-up. Although participants in later stages of the study were only recruited from those with earlier data, not all twin pairs could be followed up. The reduction in sample size over ages mainly reflects intentional reductions due to available funds and sub-project eligibility rather than participants declining to continue. More detail is provided in published project overviews (Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Van Hulle, Brooker, Meyer, Lemery-Chalfant and Goldsmith2013).

Participants

Participants were recruited from statewide birth records. Average ages for the assessments were 8, 13, and 15 years, with an average sample size of 1400 individuals (700 twin pairs), plus parents. The final sample consisted of n = 1735 individual children (from 868 families) with available data in middle childhood, early, and later adolescence. All participants have data from at least one of the three time points. Figure 1 shows the sample size at different ages and available constructs. The variation in age at each assessment occasion was due to many factors (e.g., staff availability for assessment visits around the state, funding, delay for metal dental braces to be removed to allow MRI scans).

Figure 1. Assessment summary, ages, sample sizes, and constructs measured.

Parents (94.3% mothers) reported on twin’s ethnic and racial identities during each visit. 91.9% were non-Hispanic/Latinx, 4.7% were Hispanic/Latinx, with 3.4% missing data. 88.0% of twins were White, 4.5% were more than one race, 3.9% were Black, 1.1% were other race, 0.5% were Native American, 0.1% were Hmong, 0.1% were other Island/Pacific Islander, and 1.7% were missing data on race. Parents were asked their own level of education indexed by number of years of school completed, ranging from 6 (grade school) to 20+ (graduate degree). At the initial Age 8 phase, mothers had completed an average of 14.36 (SD = 2.81) years of schooling, and fathers had completed an average of 14.82 (SD = 2.64) years of schooling. Median family income was in the range from $60,001 to $70,000.

Zygosity was initially diagnosed with the Zygosity Questionnaire for Young Twins (Goldsmith, Reference Goldsmith1991). When needed, we also used hospital placentation records, and observer ratings of details of physical similarity from videotapes. Pairs with ambiguous zygosity were genotyped. The sample includes 612 MZ individuals, 512 members of a same-sex dizygotic-twin pair, and 488 members of an opposite-sex dizygotic-twin pair. We analyzed all individuals with available data, regardless of whether the cotwin’s data were available for a particular variable.

Measures

Behavior inhibition and social anxiety

BI and SA were assessed at each phase. Assessments of BI, as the focal predictor, were extensive, using questionnaires at each age and structured observation at ages 8 and 13 years. Assessments of SA were via questionnaire and structured clinical interviews with both twins and their parents.

Storytelling paradigm

We used one task from the Middle Childhood version of the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (Lab-TAB; Goldsmith et al., Reference Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley and Prescott1999) to assess social inhibition in the presence of strangers. In Storytelling, the child stands in front of multiple seated child testers and is asked to talk about what they did the prior day, with at least one prompt given by the child tester. Items scored from videotape included child’s social reticence, verbal hesitance, and avoidance. All variables had Kappa agreement of at least 0.70, with master coders (i.e., staff members with extensive training) coding at least every 10th episode to minimize coder drift. Items were z-scored and combined to create an overall Storytelling Inhibition score for each child, with internal consistency reliability of α = 0.77.

Observer ratings of approach and shyness

During the age 8 and age 13 home visits, two experimenters rated each twin’s general behavioral and affective tendencies. Three items reflect BI: initial approach/avoidance at the beginning of the home visit (physical movement away from the experimenter), initial shyness (facial and vocal hesitancy with the experimenter), and child shyness across the course of the visit. The first two items were scored on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (“Clearly moves toward the examiner; No sign of vocal, facial or postural wariness at all, smiling”) to 4 (“Moves away, hides behind mom/something; Clear-cut shyness; fearful facial expression”). The third Shyness item was based on the Behavior Rating Scales (BRS) from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, Reference Bayley1969) and was similarly scored on a 1–5 Likert scale. We averaged across observers (cross-observer r’s = 0.62, 0.54, 0.64, respectively), and then averaged the three items to reflect an overall Observer Rating of Behavior Inhibition.

At Age 8, mothers and fathers completed the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart et al., Reference Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey and Fisher2001). The CBQ assesses multiple temperament dimensions, including shyness. The CBQ response scale ranges from 1 (“extremely untrue”) to 7 (“extremely true”). The Shyness scale includes items such as “Acts shy around new people” and “prefers to watch rather than join other children playing.” Internal consistency of the CBQ Shyness scale for mothers and fathers was Cronbach’s α = 0.90 and 0.88, respectively. At ages 13 and 15, mothers and fathers completed the similar but age-appropriate Early Adolescence Temperament Questionnaire-revised (EATQ-R) (Capaldi & Rothbart, Reference Capaldi and Rothbart1992; Ellis & Rothbart, Reference Ellis and Rothbart2001), which included a corresponding Shyness scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.85, same for mothers and fathers, and 0.86, respectively, at ages 13 and 15).

Parent- and self-reported BI and SA

We also used the relevant Inhibition and Social Anxiety scales from the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ; Armstrong et al., Reference Armstrong and Goldstein2003; Essex et al., Reference Essex, Boyce and Goldstein2002) at all ages. At ages 8 and 13, both mothers and fathers rated their children’s behavior over the past six months using a three-point scale (0 = rarely, 2 = certainly applies). At ages 13 and 15, twins self-reported their own inhibited behavior. Sample items for Inhibition include the following: “When I’m around kids I don't know, I get quiet,” and “When [child] meets new kids, he/she is shy.” Sample items for Social Anxiety include “It makes me nervous or uncomfortable when I have to do things in front of other people,” and “When [child] is around kids he/she doesn't know, he/she feels nervous or uncomfortable.” Internal consistency reliability (α) for HBQ Inhibition scales ranged from 0.69 to 0.92, and for the Social Anxiety scales, they ranged from 0.78 to 0.95 for all reporters across ages.

Twins also completed the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March et al., Reference March, Parker, Sullivan and Stallings1997) at age 13, with a limited number (n = 10) completing it at age 15 as well. The MASC includes a 9-item Social Anxiety scale to assess performance related anxiety. Sample items include “I worry about other people laughing at me”, and “I worry about getting called on in class”. Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from (0 = never true about me, 3 = often true about me) with a reliability at age 13 of α = 0.83.

Other Parent- and Self-Reported Disorders. The HBQ was also used to assess other behaviors that might help elucidate specific prediction of SA, namely the Depression, Overanxious, Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant, Inattention, and Impulsivity scales. Like the SA scale, mothers, fathers, and twins reported on these behaviors across time. Sample items and reliabilities are described elsewhere (Moore et al., in press)

Diagnostic interview schedule for children – IV

We administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (DISC-IV) to mothers at each age and to twins during early and later adolescence. The DISC-IV is a computer-based structured diagnostic instrument with moderate to good diagnostic reliability (Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan and Schwab-Stone2000). Here, we use symptom counts on the Social Phobia scale at each age to reflect SA. We also used symptom counts for Major Depression, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Conduct Disorder, and Oppositional-Defiant Disorder in analyses examining the specificity of SA.

Derivation of composites for analyses

The variables in Figure 1 illustrate the raw materials for composites used in the analyses. Our general approach was to account for child linear age effects within assessment periods at the outset; thus, child age in months was first regressed out of each variable and standardized residuals were saved for use in calculating composites for child behaviors. To form the composites, we used unit weighting rather than differentially weighting the different measures, in the interest of replicability. Other than sex, we used only dimensional measures, including symptom counts.

To create overall composites at each age, we regressed age out of each variable and created composites for BI and SA within reporter, but separately for ages 8, 13, and 15. For example, we combined mother reported CBQ Shyness and HBQ Inhibition at Age 8, and father reported CBQ Shyness and HBQ Inhibition at Age 8, then averaged mother report, father report, observer reported BI, and coded behaviors from the Storytelling paradigm to create an overall BI composite. This process was repeated for each age period with the relevant BI and SA variables. The convergent validity of components and internal consistency of each BI and SA composite can be assessed by examining within age correlations (see Table 1). In general, there were consistent moderate to strong correlations within each composite, across reporter and measurement. A notable exception is Age 8 BI, with the Storytelling Paradigm showing little or no relation to other items within the composite. Nonetheless, observational tasks that assess similar behaviors to those that are parent or self-reported can show minimal association but still reflect similar processes across varying contexts (Gagne et al., Reference Gagne, Van Hulle, Aksan, Essex and Goldsmith2011); thus, we include inhibition scored during the Storytelling task in our assessment of Age 8 BI.

Table 1. Intercorrelations within behavior inhibition and social anxiety constructed composites

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. 1The MASC at age 15 was completed by twins who had not completed the MASC at age 13. The sample size overlap is small (n = 10) with other age 15 items. Thus, the correlations, though large, are not significant.

For analyses of the specificity issue, this process was repeated for the following dimensional symptom domains using HBQ scales and DISC symptom counts in the same manner described for SA: depression, generalized anxiety, ADHD, conduct disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder.

Potential moderators

Overprotective parenting

Mothers’ parenting was assessed using the 35-question short form of the Child-Rearing Practices Report (CRPR; Block, Reference Block1965). Mothers rated each statement on the questionnaire from 1 (i.e., strongly disagree) to 6 (i.e., strongly agree). Overprotective parenting specifically was assessed using the inverse of the 7-item Encouraging Independence subscale. Items included “I try to let my twins make many decisions for themselves” and “I intend to give my twins a good many duties and family responsibilities.” Internal consistencies ranged from 0.49 to 0.61.

Parent internalizing psychopathology

Parents completed the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Wing, Wittchen and Helzer1988) and the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Patrick et al., Reference Patrick, Curtin and Tellegen2002; Tellegen, Reference Tellegen1985). The CIDI is a structured interview that assesses symptoms of psychopathology across multiple domains according to criteria from the ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Parents completed the interview via telephone. The CIDI has high test-retest reliability (Kessler & Üstün, Reference Kessler and Üstün2004). Both mothers and fathers completed the modules depression, generalized anxiety, dysthymia, and social phobia. The MPQ is a self-report questionnaire with response options following a four-point Likert-type scale, ranging from “Definitely True” to “Definitely False.” We used the Well-being subscale, which is reverse scored to indicate depressive tendencies, as well as the Stress Reaction scale which is indicative of anxious behaviors in parents.

We calculated a sum score for CIDI diagnoses to reflect additive effects of parents’ internalizing psychopathology at child ages 8 and 13. The four CIDI internalizing items and the MPQ Well-being and Stress Reaction scores were then z-scored and averaged to create an overall mother and father internalizing score for each of the two variables for each parent at each age.

Parenting stress

A brief version (37-item, 5-point Likert scale) of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin, Reference Abidin1990) was administered at ages 8, 13, and 15, reported by mothers (α = 0.83, 0.80, 0.80, respectively). The scales range from “Strongly Agree” to “Strongly Disagree.” We identified 5 subscales using item-level factor analysis: attachment, restrictions of role, relationships with spouse, sense of competence, and social isolation. Subscale scores were totaled at each age, with higher scores indicating high parenting stress. We z-scored these scales and combined into a mean composite to use for further analyses.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

To estimate SES, we used two items from the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index (Hollingshead, Reference Hollingshead1975). Traditionally, the Hollingshead includes sex and marital status, but we limited our calculation to Hollingshead Education scores (ranging from 1 “less than seventh grade” to 7 “graduate professional training”), and Hollingshead Occupation codes (ranging from 1 “farm laborers/menial service workers” to 9 “higher executives and major professionals”). Each Occupation and Education score was weighted by 5 and 3, respectively, before computing a final raw Hollingshead score per family. Though the original Hollingshead Index was developed in 1970, we used information from the 2000 United States Census Bureau to assign codes for parents’ occupation. Descriptive statistics for family SES in the current study were as follows: age 8: mean = 45.48 (SD = 11.27), range = 8 to 66; age 13: mean = 45.93 (SD = 10.55), range = 14 to 66; age 15: mean = 46.00 (SD = 11.17), range = 17 to 66.

Peer victimization

At age 13 and 15, twins reported on their own and their cotwin’s experiences using seven items on the HBQ that reflect peer victimization and social experiences (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Planalp, Van Hulle and Goldsmith2019). Seven questions asked respondents to choose between two opposing options that were stated equivalently (e.g., Kids say mean things to me, or Kids don't say mean things to me; Some kids at school verbally or physically threaten me, or Kids at school don't verbally or physically threaten me). After selecting which option best described their experience, respondents rated it on a scale from 1 (sort of like me) to 3 (really like me). Responses were then converted to a 6-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more severe peer victimization. The 7 HBQ peer victimization items were averaged to calculate a total peer victimization scale score for each individual and their co-twin. Self (α = 0.88) and co-twin (α = 0.90) reports of peer victimization were correlated, r = 0.58, p < 0.001, so we computed a mean composite representing overall peer victimization for each adolescent.

Pubertal timing

We used a multi-method approach to measure pubertal development at ages 13 and 15. Tanner stages (Tanner, Reference Tanner1962), the parent- and self-reported Picture-Based Interview about Puberty (PBIP; Morris & Udry, Reference Morris and Udry1980), and the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Crockett, Richards and Boxer1988) were administered. The PBIP shows good reliability and validity for measuring pubertal development (Coleman & Coleman, Reference Coleman and Coleman2002). Using scoring developed by Shirtcliff et al. (Reference Shirtcliff, Dahl and Pollak2009) and used in prior research with this sample (Phan et al., Reference Phan, Van Hulle, Shirtcliff, Schmidt and Goldsmith2021), we calculated pubertal stage scores that mapped onto the Tanner stage scale metric. Tanner stages and the pubertal development stage were standardized within measure and then averaged to form a puberty score. A pubertal timing variable was calculated at ages 13 and15 separately by regressing youths’ age at the time of puberty measures collected on the puberty score and then using the residuals (Mendle et al., Reference Mendle, Beltz, Carter and Dorn2019). A higher pubertal timing score represents youth who are more advanced in pubertal stage relative to same-age peers. Standardized residual scores were then used for primary analyses.

Child sex

Sex was reported at age 8 by parents. Gender identity beyond the binary was not systematically assessed.

Overview of analytic approaches

Rather than attempting to capture all elements of our investigation into a single highly elaborated model with many inter-dependent findings, we focus on a series of specific analyses to address the issues that motivated our study. We do not focus on measurement issues due to earlier publications on measurement with this sample and related samples (e.g., Gagne et al., Reference Gagne, Van Hulle, Aksan, Essex and Goldsmith2011; Planalp et al., Reference Planalp, Van Hulle, Gagne and Goldsmith2017).

Phenotypic analyses

Directionality of effects using cross-lagged panel analysis

We tested the reciprocal relationship between BI and SA across childhood and adolescence using a partially random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM; Berry & Willoughby, Reference Berry and Willoughby2017; Hamaker et al., Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015) with Mplus v. 7.3 (Hamaker et al., Reference Hamaker, Kuiper and Grasman2015). In a RI-CLPM, each variable is regressed on its own lagged score from the previous measurement occasion, as well as on the lagged score of the other variable. However, to account for variability within individuals as well as between individuals, as in the standard CLPM, we estimated a random intercept for BI. Notably, because there was very little variance in Age 8 mother report of SA, the random intercept for SA was not appropriate in these data, indicated by an ill-fitting and error prone model. Therefore, we fit a partial RI-CLPM to BI but not SA (illustrated in Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cross Lagged Panel Model Examining Bidirectionality of BI and SA. A random intercept was implemented for BI but constrained to equal “0” for SA due to low variability at Age 8.

Specificity of prediction of SA from BI

Pearson correlation analyses that account for within family clustering of data using the Mplus clustering option were used to examine the association of BI at each age with concurrent and later symptoms of general anxiety, depression, ADHD, conduct, and oppositional-defiant disorder. After r-to-z transformations, we compared the relative magnitude of the correlations between BI and SA with other psychopathology dimensions (Eid et al., Reference Eid, Gollwitzer and Schmitt2011; Lenhard & Lenhard, Reference Lenhard and Lenhard2014). No results warranted follow-up with multivariate approaches.

Multiple moderator approach for BI-to-SA predictions

In the moderation analyses, multi-level regression using SAS proc mixed accounted for familial clustering of twins. When examining family wide processes, data from members within a family are nonindependent and do not fit standard regression assumptions (Gonzalez & Griffin, Reference Gonzalez, Griffin, Cooper, Camic, Long, Panter, Rindskopf and Sher2012; Planalp et al., Reference Planalp, Van Hulle and Goldsmith2019). This model accounts for the within-family similarities by imposing a compound symmetric covariance matrix to twin data. First, we examined age group (mean ages 8, 13, and 15) and sex as moderators. Then, we tested each of the other potential moderators, one at a time, along with age group and sex. Each regression at this stage included all main effects and all two-way and three-way interactions. From these five regression models, we carried the subset of moderators that showed main effects or two-way interactions with BI forward to the final model. In the final model, we probed significant interactions using simple slopes analysis (Aiken et al., Reference Aiken, West and Reno1991), as recommended by Preacher et al. (Reference Preacher, Curran and Bauer2006) for multi-level modeling.

Biometric analyses

Bivariate twin analyses. Twin ICCs (Table 3) provide an easily understood descriptive measure of twin similarity. Doubling the difference between MZ and DZ intraclass (similarity) correlations estimates heritability (Falconer & Mackay, Reference Falconer and Mackay1996). We also used bivariate biometric model fitting with Cholesky decomposition, using Mplus (version 7.3; Muthen & Muthen, Reference Muthen and Muthen1998) to examine the genetic and environmental bases of phenotypic covariances between BI and SA. We used a bivariate Cholesky decomposition that hypothesized a specific ordering of variables as we were interested in genetic and environmental bases of prediction of adolescent SA from childhood BI. Childhood BI was measured at age 8, and Adolescent BI was considered an average of the age 13 and 15 SA composites. Figure 3 summarizes the bivariate biometric model with the Cholesky approach. We also explain the interpretation more when the genetic results are presented in the Results section.

Figure 3. (a) describes the bivariate model of genetic and environmental influences linking childhood BI and adolescent SA. A1 and A2 = genetic influences on BI and SA, respectively; C1 and C2 = shared environmental influences on BI and SA, respectively; E1 and E2 = nonshared environmental influences on BI and SA, respectively; a11 = effect of A1 on BI; c11 = effect of C1 on BI; e11 = effect of E1 on BI; a21 = effect of A1 on SA; c21 = effect of C1 on SA; e21 = effect of E1 on SA; a22 = effect of A2 on SA; c22 = effect of C2 on SA; e22 = effect of E2 on SA. (b) Illustrates only significant pathways in our model.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of BI, SA, and their potential moderators

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Number (8, 13, 15) indicates age at which measured. BI = behavioral inhibition; SA = social anxiety; PeerVic = peer victimization; Pub. Tim. = pubertal timing; SES = socioeconomic status’ PSI = parenting stress; OVP = overprotective parenting; F and M Int. = father or mother internalizing symptoms.

Table 3. Intraclass and cross-twin cross-trait correlations for cotwin similarity for behavior inhibition and social anxiety

Note: 1Weighted average of Twin 1 BI & Twin 2 SA and vice versa correlations using Eid et al. (Reference Eid, Gollwitzer and Schmitt2011) calculation. BI = Behavioral Inhibition, SA = Social Anxiety; number of twin pairs per correlation range from N = 144 to N = 306, depending on construct and age.

We also examined a bivariate model with scalar sex limitation, which allows genetic and environmental paths to vary for males and females. This model did not fit better than the model where the male and female paths were constrained to be equal, and thus we do not treat it further.

Results

The means, SDs, and intercorrelations of the BI and SA variables at each developmental stage and potential moderators are shown in Table 2. BI and SA variables were all intercorrelated, with correlations within the same age group substantial and higher than most of the stability correlations. We also note that child sex was a moderate but consistent correlate of both BI and SA, with females higher on both. Child sex also correlated with other variables, suggesting that it should figure prominently in our analyses. Table 3 shows intraclass correlations indexing cotwin similarity for BI and SA for MZ and same and opposite sex DZ twin groups. BI was highly heritable and SA, less so.

The cross-twin, cross-trait correlations, which foreshadow the bivariate genetic analyses, were modest in size. The association of BI in one twin with SA in the cotwin was always stronger in MZ than in DZ pairs, which implies genetic effects on the BI association with SA. Further interpretation of the bivariate association is reserved for the model-fitting approaches below.

Is the prediction of SA from BI unidirectional and specific?

Examination of unidirectionality using cross-lagged panel analysis

As Figure 2 shows, both BI and SA are moderately stable over time (0.35 and 0.36 for BI, and 0.30 and 0.49 for SA, from one age to the next). Moreover, the within-age, cross-trait correlations were 0.36, 0.63, and 0.14 at the three ages. When we move to the cross-lagged coefficients of most interest here, we see that the predictions from earlier SA to later BI were as strong as the reverse predictions (the predicted BI-to-SA), lending no support to a unidirectionality argument.

Specificity of BI-to-SA links

Controlling for twin interdependence, we computed Pearson correlations between the BI variables at each age with contemporaneous scores on depression and generalized (non-social) anxiety. The center column in Table 4 shows, for instance, that at age 13, BI correlated 0.21 with depression and 0.24 with generalized anxiety, whereas the correlation with SA (r = 0.53) was almost twice those magnitudes. Some level of correlation of BI with depression and generalized anxiety symptoms should be expected, as these latter two variables show correlations in the 0.50-0.60 range with SA. We also examined specificity of BI’s prediction of SA in relation to three externalizing measures: ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder. Here, Table 4 shows mostly inverse or near-zero correlations, even when the measures were from the same age group. Small but significant negative correlations, consistent with a small protective effect of high BI for externalizing problems, emerged in the age 8 and 13 data.

Table 4. Behavior inhibition specificity: correlations with other psychopathology variables and tests of z-transform differences

Note: Correlations consider within family similarity using clustering. The z-transform of each correlation (e.g., BI with DEP) is compared to BI with SA, using a dependent samples analysis and differences are represented with listed p-values. Asterisks indicate that the correlation is significantly different from 0: ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05. BI = behavioral inhibition, SA = social anxiety, DEP = major depressive disorder, ANX = generalized anxiety disorder, ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, CD = conduct disorder, ODD = oppositional defiant disorder. All variables are dimensional and not diagnoses.

Longitudinal correlations between age 8 BI and later psychopathology variables (column 1 of Table 4) followed the same patterns, with the strongest relations between BI and SA compared with other outcomes. To confirm that BI specifically predicts SA, we used r-to-z transformations, accounting for the dependency of calculating correlations within the same sample. The differences between the resulting z-transforms were compared using t-tests to evaluate the relative strength of correlations between BI and SA with other psychopathology dimensions (see Table 4) (Eid et al., Reference Eid, Gollwitzer and Schmitt2011; Lenhard & Lenhard, Reference Lenhard and Lenhard2014). We conclude that BI does show relative specificity in predicting SA in relation to other internalizing symptoms and clear specificity in relation to externalizing symptoms.

Is the prediction of SA from BI genetically mediated and does SA show residual genetic variance that is independent of genetic effects on BI?

Given the phenotypic associations between BI and SA that the cross-lagged panel analysis demonstrated, we next sought to examine the genetic and environmental underpinnings of the association. To simplify the phenotypic aspects of the model, we needed a single predictor and a single outcome. We also sought to separate the predictor and outcome temporally to clarify interpretation of results. As the predictor, we used childhood BI at age 8 and as the outcome, we estimated adolescent SA as the mean of SA at ages 13 and 15. The ordinary phenotypic correlation of these BI and SA composites was 0.16 (p < 0.001).

Bivariate model with Cholesky decomposition

The diagram presenting the parameter estimates (Figure 3b, with model characteristics provided in the figure note) has three interesting features. The left side shows additive (A) genetic, common environmental (C) and nonshared, or unique, environmental (E) parameter estimates that compose the phenotypic variation in BI. As anticipated by the ICCs provided in Table 3, the C estimate was empirically driven to zero and was thus set to zero. The path estimates are unsquared, but squared estimates provide a numeric value for overall heritability (genetic influence) of the trait; thus, the 0.84 path from A to childhood BI must be squared to estimate heritability (h 2) of BI to be 0.71. If we also square the non-shared environmental path 0.542 = 0.29, we see that 0.71 + 0.29 = 1.00; that is, 100% of the phenotypic variance. The cross-variable paths (BI-to-SA) estimate the variance in SA accounted for by genetic and environmental factors that also impact BI. The path estimate of 0.25 for A (more than twice its standard error) demonstrates a significant genetic path to SA from earlier BI. Finally, the diagram also demonstrates substantial genetic input to variation in adolescent SA that is independent of the genetic basis of BI (0.702 = 0.49, so 49% of the unique variance of SA is attributable to genetic effects). More of the genetic variance in SA is unique than is contributed by BI.

Do specific variables from the literature moderate the prediction of SA from BI?

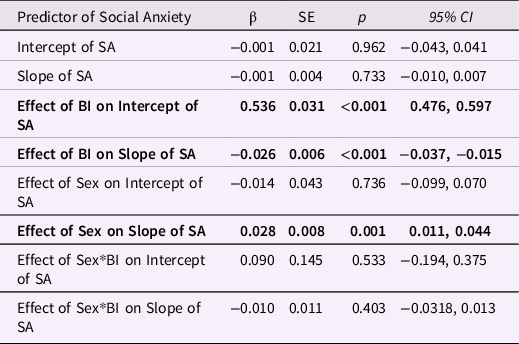

As noted in the Method section, we first constructed a “base model” of child sex and development period (ages 8, 13, and 15) moderating the BI-to-SA prediction, using a multilevel model that accounted for the paired nature of twin data. In this model, the age indicates the slope of SA across ages 8, 13, and 15. Results of this model are provided in Table 5. Results show the expected strong main effect of BI on SA (Est = 0.536) as well as a strong relation between BI and changes in SA (Est = −0.026); the significant effect of BI on the slope, or changes in SA, indicates that BI at the later ages was most strongly associated with SA. However, sex did not interact with BI in the model predicting SA. Sex did, however, interact with age, such that SA increased with age for girls and decreased for boys.

Table 5. “Base model” regression analysis of the role of age group and sex in the prediction of social anxiety from behavioral inhibition

Note: N = 1711 individual children with available data; SA = Social Anxiety as the outcome of interest.

With the model in Table 5 as our baseline, we tested each of the other potential moderators, sequentially, to determine if they interacted with BI to predict SA. Of the seven potential moderators, pubertal timing did not interact with BI, nor did it show a main effect; mothers’ internalizing did show a main effect, but it did not moderate the BI-to-SA prediction. Over-protective parenting, family stress, adolescent peer victimization, and SES all significantly moderated the effect of BI on SA. Fathers’ internalizing showed only a marginal (p = 0.07 moderating effect, but that effect was qualified by a significant three-way interaction involving BI and child sex. We carried over-protective parenting, family stress, adolescent peer victimization, SES, and paternal internalizing forward into a final model to examine moderation more comprehensively.

Table 6 presents the final “conditional model” which includes predictors that were significant in individual moderator analyses. Main effects that did not involve BI are noteworthy. Four significant main effects on levels in SA emerged: a strong effect of BI (Est. = 0.572), a medium effect of parenting stress (Est. = 0.183), and a modest effects of father internalizing (Est. = 0.110) and over-protective parenting (Est. = 0.103); SA was generally higher when each of these variables was also higher. Peer victimization had a significant main effect on changes in SA across time (Est. = 0.037), such that adolescents experiencing lower peer victimization at age 13 had slightly lower SA than those experiencing higher rates of peer victimization; the same relation was not found by age 15.

Table 6. “Conditional model” regression analysis of the role of moderators on the prediction of adolescent social anxiety from behavioral inhibition

Note. SA = Social Anxiety; BI = behavioral inhibition; Sex is coded 1 = female, −1 = male.

Our key question about moderation of the effects of BI yielded one strong interaction in the final model with parenting stress (Est. = 0.398). In general, when children were higher in BI, they also experienced more SA, particularly when parenting stress was higher at age 8. BI also interacted with Parenting Stress to predict the slope of SA, such that children with higher BI developed SA through adolescence at a faster rate when parenting stress was low. We also note that the significance level of the 2-way interaction of BI with SES was p = 0.038; this effect is small (Est. −0.009) but notable given its independence from the parenting stress interaction.

Discussion

Summary of results

Our results are grounded in a substantial empirical literature about BI and anxiety, and our large-study findings strengthen some trends in the literature, weaken others, and provide novel findings. We begin by summarizing our answers to the research questions. We do not find evidence that the direction-of-effects in the BI-SA association is unidirectional—that is, only or predominately from BI to SA. We do conclude that BI robustly predicts SA. From a correlational perspective, this prediction is relatively specific, in the context of other internalizing problems and clearly in relation to externalizing problems. An ancillary finding is that BI does not appear to protect strongly against externalizing problems.

BI and SA are both moderately heritable, BI more than SA. The genetic influences on BI also impact differences in SA, as do the nonshared environmental effects, to a much weaker degree. Still, SA variability is influenced by other genetic effects that are independent of BI.

Our examination of predictors of SA began with the raw correlations in Table 2, which showed that all the potential moderators except pubertal timing significantly correlated with SA, as the literature would have predicted. Only one of these variables—peer victimization—was reasonably known beforehand for our sample (Carroll, Reference Carroll2021).

We then tested variables, including measured exposures and experiences, that could—based on the literature--moderate the rather strong prediction of SA from BI. We first tested individual moderators, separately, in a series of regression models with BI, age group, and sex. In addition to age group, five variables (over-protective parenting, family stress, adolescent peer victimization, and SES) all significantly moderated the effect of BI on SA. The second set of results was presented in Table 6. Although we refer to Table 6 as presenting the final model, every stage of the analysis yields informative results. Clearly, the effects of any variable in multiple regression depends on the other predictors available for study, and we did not exhaust all possibilities.

Why are these interactions developmentally important? As in our previous work in another sample (Essex et al., Reference Essex, Klein, Slattery, Goldsmith and Kalin2010), we subscribe to the argument that interactions among variables in longitudinal data may signal branching paths toward outcomes. So, for instance, we might consider high BI children to be on a general path leading probabilistically to SA, but many of those high BI children who experience peer victimization shift to a higher risk path. The high BI children in families that experience chronic stress shift to a different higher risk path and so on for other interactions over time with BI. Such a causative nexus would help explain heterogeneity in origins of SA.

High BI need not be a necessary condition for SA. Table 6 suggests that, independently of BI, over-protective parenting and parenting stress predict SA, and some interactions are also predictive of SA independently of BI. Thus, high BI is clearly not a sufficient condition for developing SA. Children with high BI who do not develop SA might not have experienced bullying or over-protective parenting, and their parents might not have experienced stress in the parenting role.

Cautions against strong inference are warranted in some instances

The generalizability of research on twins is sometimes questioned; however, twins differ minimally from singletons in personality (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Krueger, Bouchard and McGue2002), cognitive ability (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Petersen, Skytthe, Herskind, McGue and Bingley2006), and clinical conditions (Kendler & Prescott, Reference Kendler and Prescott2006). Ours is a community sample; confining attention to clinically diagnosed SA might yield different results. Our large sample size leads to very modest effect sizes being statistically significant. The SES range is wider than in some samples, and rural representation is notable. The sample racially and ethnically matches Wisconsin’s 2018 census estimates, which means a lack of strong diversity in race and ethnicity. This lack of diversity severely limits generalizability to nonwhite groups.

Our sample size was likely under-powered for the bivariate sex limitation model (Neale & Cardon, Reference Neale and Cardon2013), and the resulting lack of significant difference in fit from the model where male and female paths were constrained to be equal should not close the door to examining these sex differences in genetic paths in a larger twin sample or with different methods. Indeed, the rejected sex limitation model suggested slightly stronger genetic mediation of the BI-to-SA path for males than for females, a finding that deserves more investigation.

Measurement considerations

As Figure 2 shows, we used core instruments to assess BI and SA at each age group. These instruments were modified (by the original authors) to make them age-appropriate (for example, the EATQ shyness items differ somewhat from the CBQ shyness items). Observations and reactions to a structured situation were possible at the younger age groups, and an additional questionnaire was used to improve the coverage for SA at the oldest age group. We strove for best-feasible-estimates for each age group, as opposed to factorial invariance. Thus, some instability across age groups could be due to measurement differences, which we judge to be favorably counter balanced by enhanced validity at each age group.

Our primary a priori concern was the measure of over-protective parenting, which was measured as the inverse of parental questionnaire items about encouraging independence. Although over-protective parenting nevertheless emerged as influential in our analyses, its role might have been underestimated relative to what we might have found with a more direct, multi-source, measurement.

Design considerations

We only studied a subset of the behavioral moderators that have been suggested for the BI-to-SA prediction. Investigators have proposed that the quality of BI should be considered. Conflicted shyness could be a subtype of BI that holds more predictive power for SA (Poole et al., Reference Poole, Van Lieshout and Schmidt2017) and dysregulated fearfulness may also signal increased risk (Buss, Reference Buss2011). Moreover, we did not include biological variables in our study. Biological variables (e.g., neuroendocrine, brain structure and activity) might serve as mediators in the types of models we investigated, a feature that would complicate the models statistically (moderated mediation) but perhaps add substantial explanatory power.

Implications of results for models of temperament-psychopathology effects

How exactly BI relates to SA remains under debate. One hypothesis suggests that the social component of BI (i.e., shyness), which we focus on here, can be conceptualized as part of a spectrum that includes SA (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Heinrichs and Moscovitch2004; Marshall & Lipsett, Reference Marshall and Lipsett1994). On the other hand, one-third of shy adults do not endorse social fears or somatic symptoms, which are two hallmarks of SA (Heiser et al., Reference Heiser, Turner, Beidel and Roberson-Nay2009). Our study’s results hold implications for the vulnerability vs. complication/scar vs. spectrum models. We must consider whether BI is a precursor (as in a spectrum model) or predisposition (as in a vulnerability model) to SA (Mumper & Klein, Reference Mumper and Klein2021). If BI acts as a precursor to later psychopathological anxiety, shared causal mechanisms are expected. If BI is instead a predisposition to anxiety problems, then shared causal processes would not be expected, or at most we would expect only partial overlap in causal mechanisms. The predisposition idea (vulnerability model) would suggest that individuals with high BI would be more likely to develop SA in certain contexts, but that these contexts are crucially important in the etiology of SA. That is, moderating elements typically must be present for a predisposition to give rise to a form of psychopathology with a partially independent etiology (Mumper & Klein, Reference Mumper and Klein2021). Of course, multiple processes can be operating, and nothing compels reality to respect our conceptual distinctions among models.

Our cross-lagged panel results support neither a strong version of the vulnerability model nor a strong version of complication/scar model. The vulnerability model would predict stronger paths from BI to later SA, and the complications/scar model would predict the opposite. Our observation of roughly equal paths for these two potentially causal associations, by default, would seem to favor a spectrum model. In other words, high SA symptoms essentially equate to extreme shyness. However, when we turn to the bivariate biometric motel, support for a spectrum model dissipates. Genetic influences can be regarded as causal influences although they are distal causes. Strong versions of spectrum models require the same causal process for the precursor and the outcome. Yet, our bivariate results show that most of the genetic variance for SA is not shared with BI. Our bivariate results favor the vulnerability model, in which BI acts as a predisposition. Our bivariate biometric model was not set up to test the complication/scar model, with its opposite direction-of-effect in the BI-SA associationFootnote 1 .

We noted above that moderation of BI’s effect by experiential variables or parental characteristics could signal branching developmental paths toward SA. In the Essex et al. (Reference Essex, Klein, Slattery, Goldsmith and Kalin2010) study, we also studied pathways to adolescent SA, but with a different sample, different ages of assessment, and a different analytic strategy. Essex et al. (Reference Essex, Klein, Slattery, Goldsmith and Kalin2010) identified two paths to adolescent SA, one that was primarily evident in females and that involved higher trait-like BI present in early childhood and the other that involved early maternal stress and subsequent elevated basal cortisol levels. The overlap with our present findings is clear. We show main effects of two parenting variables (stress and over-protectiveness) with later SA, which are independent of BI. We also show moderation of BI’s effect by several variables, three of which survive testing with the other moderators.

We conclude that hybrid models of the relationship of temperament to psychopathology, at least in the BI-to-SA domain, may be needed.

The role of children’s sex

Our finding of modest sex differences at various points in the analyses is unsurprising given a 30-year follow-up of shy boys and girls that showed different (non-psychopathological) manifestations of shyness through the life course (e.g., later marriage for males) (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Elder and Bem1988). Our meta-analysis of sex differences in temperament identified fearfulness as one of the traits for which females scored lower than males, but the meta-analytic effect size (d = −0.12) was modest and non-significant (Else-Quest et al., Reference Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith and Van Hulle2006).

Sex differences in comorbidity, course, and other features of SA are less well understood than sex differences in prevalence. However, a large epidemiological study reported that women with SA are more likely to have comorbid internalizing disorders (e.g., panic disorder, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder), whereas men with SA are more likely to have comorbid externalizing disorders (e.g., conduct disorder, pathological gambling, substance use disorder; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Schneier, Heimberg, Princisvalle, Liebowitz, Wang and Blanco2012), and we did not analyze substance misuse for this report.

We emphasize that, in general, the sex effects in our analyses were small. However, as Table 6 shows, interactions with sex were an important feature of our results. Thus, at least from the dimensional perspective, sex differences are notable but not a major independent part of the explanation of our findings, given the set of other experiential measures that we incorporated.

Implications for clinical issues

Evidence-based child and adolescent anxiety interventions are increasingly conceptualizing the client in the context of their broader family system (Chorpita & Weisz, Reference Chorpita and Weisz2009; Ehrenreich-May et al., Reference Ehrenreich-May, Kennedy, Sherman, Bilek, Buzzella, Bennett and Barlow2017). Clinicians regularly interact with parents and are sensitive to caregiver behaviors – such as overprotective parenting – that may contribute to the child’s avoidance behaviors, anxious thoughts, and reassurance seeking behaviors; our work provides further evidence for this practice. In fact, an online parental intervention has been developed to reduce over-protective parenting (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Rapee, Salim, Goharpey, Tamir, McLellan and Bayer2017). Of course, the meaning and adaptive function of parental over-protectiveness differs according to the degree of danger in the neighborhood, and racial and ethnic differences are likely correlated with these differences (Deater-Deckard, Reference Deater-Deckard2008).

Pediatric anxiety intake assessments typically identify parents’ experiential stress, but those evaluating the assessments are often not equipped to provide adult intervention services to stressed parents. Thus, we encourage health care systems to establish concrete pipelines that connect parents to accessible adult intervention services, such that some degree of coordination is possible.

We also emphasize that thorough assessment of peer victimization during childhood and adolescence is crucial for successful intervention at the family or school level (Graham & Bellmore, Reference Graham and Bellmore2007; Stadler et al., Reference Stadler, Feifel, Rohrmann, Vermeiren and Poustka2010). To the best of our knowledge, providers inconsistently ask about peer victimization during intake and intervention, yet prioritizing communication with parents and schools about whether and how peer victimization is experienced can offer significant intervention improvements. Our findings suggest a thorough peer victimization assessment could be a helpful addition to SA treatment.

Prevention programs that increase children’s self-regulation could also mitigate genetic risk of SA and other behavioral conditions. We have recently shown, for example, that the Family Check-Up increases children’s temperamental inhibitory control across childhood, and inhibitory control mediates prevention effects on adolescent outcomes including internalizing and externalizing problems (Hentges et al., Reference Hentges, Krug, Shaw, Wilson, Dishion and Lemery-Chalfant2020). Furthermore, genetic risk for child psychopathology is ameliorated for children whose families received the intervention; those at high genetic risk in the control group had lower levels of observed childhood effortful control, whereas levels of effortful control were “repaired” for children in the intervention group (Oro et al., Reference Oro, Clifford, Shaw, Wilson and Lemery-Chalfant2019).

Implications for parenting and family research