Introduction

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) are a pressing public health issue in the United States. In 2017, 19.7 million individuals aged 12 and older were diagnosed with a SUD (SAMHSA, 2017). Of adolescents aged 12–17, 7.9% were current users of illegal drugs, 9.9% were current alcohol users, and 60.7% of underage alcohol users were binge drinkers (Bose et al., Reference Bose, Hedden, Lipari and Park-Lee2017). Notably, earlier initiation of cannabis, alcohol, and tobacco are associated with increased vulnerability for high rates of substance use throughout adolescence (Bolland et al., Reference Bolland, Bolland, Tomek, Devereaux, Mrug and Wimberly2016) and later problematic involvement with both drug of initiation and different substances (Englund et al., Reference Englund, Egeland, Oliva and Collins2008; Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Boden and Horwood2008; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Ryzin and Dishion2015; Swift et al., Reference Swift, Coffey, Carlin, Degenhardt and Patton2008). Adolescent substance use can also result in detrimental social, educational, cognitive, psychosocial, and physical outcomes, along with high costs to the United States economy—approximately $600 billion annually (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992; National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018).

The literature investigating associations between predictors of adolescent substance use, specifically parenting and parent–child relationship quality, is vast. Often, parenting is assumed to influence adolescent substance use via the environment, although it is possible associations are also due to genetic influences. We examined the associations between parenting characteristics (positive, negative, and inconsistent parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents) and adolescent substance use in a longitudinal adoption study including adoptive families (adoptees, other adopted and biological children of the adoptive parents, and their adoptive parents), and nonadoptive families (matched nonadoptees, their siblings, and their parents). These associations were compared in nonadoptive and adoptive families to examine the role of passive gene–environment correlation (i.e., parental genetic predisposition influencing the association between parenting and adolescent substance use), evocative gene–environment correlation (i.e., children’s genetic predisposition influencing parenting), and environmental mediation (i.e., parenting influencing adolescent substance use).

Evidence for family environmental influences on adolescent substance use

Twin and adoption studies allow researchers to estimate the magnitude of additive genetic (a 2 ), shared environmental (c 2 ), and nonshared environmental (e 2 ) influences (Knopik et al., Reference Knopik, Neiderhiser, DeFries and Plomin2017). a 2 estimates a trait’s heritability, or the proportion of phenotypic variance accounted for by genetic differences between individuals, c 2 is the magnitude of all nongenetic influences that make family members similar (e.g., parents treating their children similarly irrespective of genetic relatedness), and e 2 is the magnitude of environmental influences that make family members dissimilar (e.g., interactions with different sets of peers). Differences in genetic relatedness of participants allow researchers to estimate a 2 , c 2 , and e 2 using biometrical models. Twin designs take advantage of the fact that and monozygotic twins share 100% and dizygotic twins share 50% of segregating genes on average. Adoption studies examine associations between adoptive relatives, who share only their environment, and associations between biological relatives, who share both their genes and environment.

Reviews of twin and adoption studies have concluded that though the magnitude of genetic and environmental influences on adolescent substance use depends on the phenotypic outcome examined (e.g., greater heritability for frequency of use than initiation of use; greater magnitude of environmental influences on adolescent alcohol versus tobacco use), studies have consistently confirmed significant shared environmental influences on adolescent substance use across phenotypes and substances (Hopfer et al., Reference Hopfer, Crowley and Hewitt2003; Lynskey et al., Reference Lynskey, Agrawal and Heath2010; Meyers & Dick, Reference Meyers and Dick2010; Young et al., Reference Young, Rhee, Stallings, Corley and Hewitt2006). Moreover, there are significant correlations between shared environmental influences on use of different types of substances during adolescence (e.g., Young et al., Reference Young, Rhee, Stallings, Corley and Hewitt2006). Associations between putative familial environmental influences and adolescent substance use may be best explained by environmental mediation or genetic influences, depending on the predictor examined. For example, studies suggest that sibling substance use, familial involvement, and familial functioning influence adolescent substance use via environmental mediation (e.g., Rose et al., Reference Rose, Dick, Viken, Pulkkinen and Kaprio2001; Silberg et al., Reference Silberg, Rutter, D’Onofrio and Eaves2003). In contrast, the association between parental and adolescent substance use is primarily due to common genes (e.g., Koopmans & Boomsma, Reference Koopmans and Boomsma1996).

Putative environmental influences on adolescent substance use

Positive and negative parenting

Exposure to more positive parenting practices (e.g., higher parental support, responsiveness, involvement, and acceptance) throughout development may be protective against adolescent use of specific substances (alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use: Donaldson et al., Reference Donaldson, Handren and Crano2016; Eiden et al., Reference Eiden, Lessard, Colder, Livingston, Casey and Leonard2016; King et al., Reference King, Vidourek and Merianos2015; Koetting O’Byrne et al., Reference O’Byrne, Haddock, C. and Poston2002; Rose et al., Reference Rose, Dick, Viken, Pulkkinen and Kaprio2001; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Cheong, Zaravinos-Tsakos, Lubman and Jorm2017) and general substance use (Anderson & Henry, Reference Anderson and Henry1994; Dishion & Reid, Reference Dishion and Reid1988; Kaplow et al., Reference Kaplow, Curran and Dodge2002; Sitnick et al., Reference Sitnick, Shaw and Hyde2014; Trucco, Reference Trucco2020). Meta-analyses have concluded that positive parenting characteristics assessed as early as toddlerhood predict adolescent alcohol use and externalizing problems (which are strongly linked to adolescent substance use; Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Boden and Horwood2008; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992), even after controlling for initial levels of childhood externalizing problems (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017). The influence of early positive parenting on adolescent substance use may also be indirect, via later parenting characteristics such as parental knowledge (i.e., awareness of children’s activities and whereabouts) and monitoring, that are in turn protective against adolescent use of various substances (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Reifman, Farrell and Dintcheff2000; Eiden et al., Reference Eiden, Lessard, Colder, Livingston, Casey and Leonard2016; Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein and Winslow2015; Sitnick et al., Reference Sitnick, Shaw and Hyde2014). Moreover, these associations may be causal, as opposed to simply correlational, in nature. For example, a review of longitudinal randomized control parenting interventions found that increased positive parenting behaviors in childhood had significant long-term direct and indirect (via parent–child relationship quality assessed in adolescence) effects on adolescent substance use (Sandler et al., Reference Sandler, Ingram, Wolchik, Tein and Winslow2015).

Literature also indicates positive associations between negative parentingFootnote 1 and adolescent substance use. Reviews have concluded that higher levels of parental permissiveness, withdrawal of intimacy (i.e., interpersonal distancing), neglect, and rejection are positively associated with adolescent substance use, risk of substance use, and SUDs of multiple substances (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992; Kuntsche & Kuntsche, Reference Kuntsche and Kuntsche2016). For example, parental hostility may predict earlier onset of alcohol use in girls (White et al., Reference White, Johnson and Buyske2000) and current substance use frequency and quantity in both sexes (Johnson & Pandina, Reference Johnson and Pandina1991; White et al., Reference White, Johnson and Buyske2000). Inconsistent discipline (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992; Krohn et al., Reference Krohn, Larroulet, Thornberry and Loughran2019; Molina et al., Reference Molina, Donovan and Belendiuk2010; Vicary & Lerner, Reference Vicary and Lerner1986) or lability in parenting characteristics (Lippold et al., Reference Lippold, Hussong, Fosco and Ram2018) are positively associated with child externalizing problems, substance initiation, and substance use (e.g., alcohol, marijuana, polysubstance use), even after controlling for baseline levels of the outcomes and developmental trends (Lippold et al., Reference Lippold, Hussong, Fosco and Ram2018). In addition to influencing adolescent substance use directly, negative parenting may act indirectly via developmental cascades, such that negative parent–child interaction influences inhibitory control in middle childhood, which then influences general adolescent substance use (Otten et al., Reference Otten, Mun, Shaw, Wilson and Dishion2019).

Parent–child relationship quality

Various aspects of parent–child relationships in later childhood and adolescence are also associated with adolescent substance use over time (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Hops and Duncan1997; Dembo et al., Reference Dembo, Grandon, La Voie and Schmeidler1986; Drapela & Mosher, Reference Drapela and Mosher2007; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brewer, Gainey, Haggerty and Catalano1998; Foshee & Bauman, Reference Foshee and Bauman1992; Neighbors et al., Reference Neighbors, Clark, Donovan and Brody2000; Tilson et al., Reference Tilson, McBride, Lipkus and Catalano2004; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Cheong, Zaravinos-Tsakos, Lubman and Jorm2017). Low parent–child bonding and attachment have been related to marijuana (Bailey & Hubbard, Reference Bailey and Hubbard1990; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brewer, Gainey, Haggerty and Catalano1998; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Brick, Micalizzi, Wolff, Frazier, Graves, Esposito-Smythers and Spirito2020), alcohol (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Jessor and Turbin1999; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brewer, Gainey, Haggerty and Catalano1998; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Jorm and Lubman2010 – review; Selnow, Reference Selnow1987; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kviz and Miller2012), and other drug use (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brewer, Gainey, Haggerty and Catalano1998; Kandel et al., Reference Kandel, Kessler and Margulies1978). Overall, positive relationships with parents might protect adolescents from engaging in unconventional behaviors such as illegal substance use because parents typically exercise control against norm-violating behavior (Drapela & Mosher, Reference Drapela and Mosher2007; Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Turbin and Costa1998). Thus, adolescents may be more likely to model normative behaviors when they have a strong bond with parents (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992; Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Turbin and Costa1998).

For adoptees, adoption satisfaction is a unique aspect of parent–child relationship quality that may predict adolescent substance use. Although few studies have examined adoption satisfaction as a predictor of adolescent substance use, prior literature has found significant associations between adoption satisfaction, including parents’ perceptions of the compatibility of an adoptee within the family, and adolescent conduct problems (Grotevant et al., Reference Grotevant, Wrobel, van Dulmen and Mcroy2001; Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rhee, Corley, Rhea, Wadsworth and DeFries2011), a robust predictor of substance use (Conner & Lochman, Reference Conner and Lochman2010). To broaden this literature, we examined adoption satisfaction reported in adolescence as a predictor of adolescent substance use. Notably, compatibility within the family is related to increased quality of communication between parents and children (Lamb & Gilbride, Reference Lamb, Gilbride and Ickes1985). As such, we controlled for adoption satisfaction in analyses examining other aspects of parent–child relationship quality assessed in adolescence.

Orientation to parents

In addition to parent–child relationship quality (e.g., parent–child bonding and attachment), orientation to parents characterized by an open, trusting relationship and communication between parents and their children about topics such as personal problems may be protective against adolescent alcohol and marijuana use (Lushin et al., Reference Lushin, Katz and Lalayants2019). Greater self-disclosure by adolescents to parents may result in more parental knowledge of adolescent activities, and parental knowledge is a negative predictor of adolescent substance use (Kapetanovic et al., Reference Kapetanovic, Skoog, Bohlin and Gerdner2019). These associations may be causal, as randomized interventions focusing on parent–adolescent communication have resulted in reductions in concurrent adolescent substance use (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, Reference Kuntsche and Kuntsche2016). Additionally, compatibility between the values of parents and friends, an additional aspect of orientation to parents, may also be protective against adolescent substance use of multiple substances (Albrecht & Caruthers, Reference Albrecht and Caruthers2002; Claes et al., Reference Claes, Lacourse, Ercolani, Pierro, Leone and Presaghi2005; Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Van Den Bos, Vanderryn, Costa and Turbin1995). As stated above, parents typically model conventional attitudes and behaviors related to substance use (Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, Brewer, Gainey, Haggerty and Catalano1998; Hwang & Akers, Reference Hwang and Akers2006; Kandel et al., Reference Kandel, Kessler and Margulies1978). Agreement in values between parents and peers, whose behaviors and attitudes also influence adolescent substance use (Curran et al., Reference Curran, White and Hansell2000; Hwang & Akers, Reference Hwang and Akers2006; Kandel & Chen, Reference Kandel and Chen2000), may indicate a social environment more inclined towards normative values that are protective against adolescent substance use.

The possible role of gene–environment correlation in the associations between parenting and adolescent substance use

The studies cited above investigate parental influences on adolescent substance use without addressing the possibility of genetic influences on the parenting environment. It is important to consider the evidence of genetic influences on putative environmental factors such as parenting (Kendler & Baker, Reference Kendler and Baker2007) and the possibility that common genes shared by parents and their genetically related children may influence both the familial environment provided by parents and adolescent substance use.

Nonrandom, genetically influenced environmental exposures are known as gene–environment correlations (rGE; Knopik et al., Reference Knopik, Neiderhiser, DeFries and Plomin2017; Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, DeFries and Loehlin1977; Scarr & McCartney, Reference Scarr and McCartney1983). There are three forms of rGE: active, when children seek environments given their genetic tendencies; evocative, when a child’s genetically influenced behavior evokes environmental responses; and passive, when a parent’s genetic predisposition influences the child’s environment (e.g., through parenting behavior). Studies including biologically related family members (e.g., twin designs) can differentiate between rGE and environmental mediation by comparing the magnitude of correlations of parenting characteristics received by monozygotic versus dizygotic twins (evocative rGE) or correlations between parenting characteristics of monozygotic versus dizygotic twin parents (passive rGE; Neiderhiser et al., Reference Neiderhiser, Reiss, Pedersen, Lichtenstein, Spotts, Hansson, Cederblad and Elthammer2004).

Adoption studies can also determine whether associations between putative environmental factors and outcomes are due to passive rGE or environmental mediation. In adoptive families, associations between the environment and outcome are not influenced by the genes shared by parents and children (Purcell & Koenen, Reference Purcell and Koenen2005; see Figure 1). Significant associations between parenting and adolescent substance use in adoptive families would be suggestive of environmental mediation (in the absence of selective placement) because adoptive parents do not transmit genes to their adopted children. If correlations between these putative environmental factors and adolescent substance use are significant and higher in nonadoptive than adoptive families, results would suggest passive rGE.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for investigating passive rGE, evocative rGE, and environmental influences. Note: Dashed lines represent evocative rGE influences, which are not distinguishable from environmental influences by comparing the association between the family environment and the child trait in nonadoptive and adoptive families (in the absence of adoptive and nonadoptive sibling pairs). Adapted from Behavioral Genetics, 7 th Ed. (118), by V. S. Knopik et al., Reference Knopik, Neiderhiser, DeFries and Plomin2017, Worth Publishers. Copyright [2017] by Worth Publishers.

The comparison of correlations between putative environmental factors and outcomes in adoptive and nonadoptive families does not account for evocative rGE. Children’s genetically influenced characteristics (e.g., early temperamental characteristics associated with adolescent substance use) may evoke more negative parenting by either adoptive or biological parents. Meta-analytic results indicate that evocative rGE influences a range of parenting characteristics, including positivity, affection, and involvement (Klahr & Burt, Reference Klahr and Burt2014). The literature evaluating the influence of evocative rGE on associations between parenting characteristics and adolescent substance use is limited, although prior studies suggest that evocative rGE influences associations between parenting characteristics such as monitoring (Elam et al., Reference Elam, Wang, Bountress, Chassin, Pandika and Lemery-Chalfant2016) and knowledge (Kuo et al., Reference Salvatore, Barr, Aliev, Anokhin, Bucholz, Chan, Edenberg, Hesselbrock, Kamarajan, Kramer, Lai, Mallard, Nurnberger, Pandey, Plawecki, Sanchez-Roige, Waldman, Palmer and …2021) and adolescent substance use.

Present study

The present study examined associations between putative environmental factors (parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents) and adolescent substance use and whether these associations are primarily due to genetic influences or environmental mediation by comparing associations between adoptive and nonadoptive families. We examined a latent substance use frequency factor with loadings on tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, and illegal substance use as our outcome, because prior literature suggests that polysubstance use is common in adolescence and young adulthood (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Young, Hopfer, Corley, Stallings, Crowley and Hewitt2009), there is a common latent factor underlying polysubstance use in adolescence (Young et al., Reference Young, Rhee, Stallings, Corley and Hewitt2006; Zellers et al., Reference Zellers, Iacono, McGue and Vrieze2021), and that parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents influence adolescent substance use across many different substances (e.g., Kuntsche & Kuntsche, Reference Kuntsche and Kuntsche2016; Sitnick et al., Reference Sitnick, Shaw and Hyde2014; Trucco, Reference Trucco2020).

Hypothesis I: Associations between parenting characteristics and adolescent substance use

We hypothesized that inconsistent and negative parenting would be positively correlated with adolescent substance use, whereas positive parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents would be negatively correlated with adolescent substance use, based on the findings of prior research (Dishion & Reid, Reference Dishion and Reid1988; Drapela & Mosher, Reference Drapela and Mosher2007; Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Boden and Horwood2008; Foshee & Bauman, Reference Foshee and Bauman1992; Kaplow et al., Reference Kaplow, Curran and Dodge2002; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017). Exploratory analyses investigated whether associations were significant after controlling for parent socioeconomic status,Footnote 2 pubertal timing, and adoption satisfaction and whether there were sex differences in associations.

Hypothesis II: The role of passive rGE versus environmental mediation in associations between parenting characteristics and adolescent substance use

Prior adoption studies examining associations between parenting characteristics and child externalizing behaviors (Bornovalova et al., Reference Bornovalova, Cummings, Hunt, Blazei, Malone and Iacono2014) and substance use (Samek et al., Reference Samek, Keyes, Hicks, Bailey, McGue and Iacono2014) have found equivalent correlations between adoptive and nonadoptive familiesFootnote 3 . Thus, we hypothesized that the association between parenting (i.e., positive, inconsistent, and negative parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents) and adolescent substance use would be best explained by environmental mediation, rather than passive rGE.

The influence of evocative rGE on parenting characteristics

The present study compares adoptive and nonadoptive sibling pairs to evaluate the role of evocative rGE on parenting characteristics (i.e., to determine if genetically influenced traits in children related to substance use evoke different expression of parenting characteristics).Footnote 4 Evidence for evocative rGE would be suggested if sibling correlations for parenting characteristics are higher in nonadoptive than adoptive sibling pairs, such that sibling pairs with greater genetic similarity receive more similar parenting. Our analysis of evocative rGE was exploratory due to the limited scope of the existing literature.

Method

Transparency and openness

We report how we determined our sample size, all manipulations, and all measures in the study. Data analyzed in this study are available by emailing the corresponding author, except where participant directives do not permit us to do so. Requests for data require completion of a data use agreement, documentation of training on the protection of human subjects, and the purpose of use. Analysis code for this study is available by emailing the corresponding author. Data were analyzed using MPlus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). This study’s design, hypothesis, and analysis plan were preregistered through Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/8msvh/).

Participants

The Colorado Adoption Project (Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Bricker, Wadsworth and Corley2013) includes 245 adoptive families and 245 matched nonadoptive families. The project was initiated in 1975 and participants were enrolled through 1983. This project is an ongoing longitudinal study approved by the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board. Birth mothers were recruited from religious agencies, and their children were briefly placed in foster homes after birth. Typically, children were placed into the home of their adoptive family within 1 year of birth. Seventy-five percent of the 328 adoptive parents recruited for the study by agency social workers agreed to participate. Nonadoptive families were recruited through regional hospitals. These families were matched with the adoptive families on adoptee sex, number of children in the family, father’s occupational status, father’s education, and father’s age. Evidence for minimal selective placement and in-depth descriptions of sample representativeness and parental socioeconomic status is discussed in (DeFries et al., Reference DeFries, Plomin and Fulker1994; Plomin et al., Reference Plomin, DeFries and Fulker1988; Plomin & DeFries, Reference Plomin and DeFries1985; Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Bricker, Wadsworth and Corley2013). Typically, after the recruitment of adoptees and matched nonadoptees, the next younger child in the family was also recruited. Ninety-five percent of adoptive parents and 90% of birth parents reported their ethnicities as non-Hispanic White, and there were no transracial adoptions in the sample. The present study includes data from 395 adoptees (194 girls, 201 boys; either the initial adoptees recruited from the 245 adoptive families or their adopted siblings), 491 nonadopted children (either biological children within adoptive families or children in nonadoptive families; 219 girls, 242 boys), 485 adoptive parents (244 mothers, 241 fathers), and 490 nonadoptive parents (250 mothers, 250 fathers). Attrition occurred early in the study due to limited efforts to update family contact information. When children reached age 16, re-enrollment efforts resulted in retention of 90% for adoptive and 95% for nonadoptive families (Rhea et al., Reference Rhea, Bricker, Wadsworth and Corley2013).

Measures

Measures validation

Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA) and CFA were conducted to assess reliability and construct validity of the measures (see Page 2 of supplement for details). These analyses were conducted using MPlus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017).

Positive parenting in early childhood

Observer ratings of mother’s parenting were assessed using the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (Caldwell HOME Scale; Bradley & Caldwell, Reference Bradley and Caldwell1984) during home visits. Assessments were conducted when children were ages 1 year (M = 1.01, SD = 0.04; N = 734), 2 years (M = 2.01, SD = 0.04; N = 695), 3 years (M = 3.01, SD = 0.04; N = 673), and 4 years (M = 4.02, SD = 0.07; N = 685).

The Caldwell HOME Scale consists of multiple subscales that measure the enrichment of the child’s home environment, such as parental involvement and provision of educational activities. We conducted exploratory factor analyses (EFA, see Page 2 of supplement for analytic approach) of items with good face validity for a “positive parenting” construct (e.g., “mom spontaneously praises child” and “mom initiates conversation”) to address how positive parenting is associated with adolescent substance use. Item responses were collapsed into ordinal variables to limit small cell sizes. See Table S1 for frequencies. EFA results indicated a one-factor model with three to four items with statistically significant factor loadings across all four groups (adopted girls, adopted boys, nonadopted girls, and nonadopted boys) at each year (see Table S7 for EFA results).

We conducted a hierarchical CFA to examine covariance among positive parenting assessed across the years. A model with a hierarchical positive parenting factor with significant factor loadings on latent positive parenting factors measured at years 1, 2, 3, and 4 fit the data well, with significant factor loadings for all items (see Figure S1). χ2 difference tests confirmed that an invariant model did not fit significantly worse than a noninvariant model (i.e., factor structure was consistent across group), Δχ2(120) = 132.863, p = 0.199 (cf. noninvariant vs. invariantFootnote 5 ).

Warm, inconsistent, and negative parenting in later childhood through adolescence

Parents reported on their parenting behaviors on the Dibble & Cohen Parent Report (Dibble & Cohen, Reference Dibble and Cohen1974). Questionnaires were completed at child ages 7 (M = 7.44, SD = 0.38), 9 (M = 8.98, SD = 0.41), 10 (M = 9.94, SD = 0.432), 11 (M = 10.72, SD = 0.48), 12 (M = 14.17, SD = 12.47), 13 (M = 12.99, SD = 0.46), 14 (M = 14.02, SD = 0.43), and 15 (M = 14.91, SD = 0.347) years. Parents reported on their parenting practices, such as discipline and involvement, and rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 6 = “always”). The measure consists of three factors (composites of mother and father report on relevant subscales): warmth (acceptance, child centeredness, sensitivity, positive involvement, shared decision-making, α > 0.80), negativity (guilt induction, hostility, withdrawal of relationship, α > 0.72), and inconsistency (inconsistent or lax discipline, detachment, α > 0.67) (see Deater-Deckard et al., Reference Deater-Deckard, Fulker and Plomin1999 for additional details and Table S2 for descriptive statistics).

CFA assessed fit of a single latent variable with loadings on parenting assessed at each age. Results confirmed good model fit for warmth and inconsistency factors, and adequate model fit for the control factor (See Figures S2, S3, and S4 respectively). Subscales at each age were significantly correlated, suggesting test–retest reliability, and had significant loadings on a single latent factor. Residual invariance across groups held for the warmth, Δχ2(24) = 13.388, p = 0.959 (cf. scalar vs. residual, see supplement for details), and inconsistency, Δχ2(24) = 32.530, p = 0.114 (cf. scalar vs. residual). Only configural invariance held across groups for negativity, such that metric invariance model fit significantly worse than the configural invariance model, Δχ2(21) = 34.378, p = 0.033 (cf. configural vs. metric).

Parent–child relationship quality

Quality of family relationships

Participants were asked eight questions regarding parent and family relationships; e.g., “I can count on my parents most of the time” from the Self-Image Questionnaire for Young Adolescents (SIQYA; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Schulenberg, Abramowitz, Offer and Jarcho1984). Questionnaires were completed from late childhood through adolescence, at child age 9 (M = 8.98, SD = 0.41), 10 (M = 9.94, SD = 0.432), 11 (M = 10.72, SD = 0.48), 12 (M = 14.17, SD = 12.47), 13 (M = 12.99, SD = 0.46), 14 (M = 14.02, SD = 0.43), and 15 (M = 14.91, SD = 0.35) years (See Table S4 for descriptive statistics), with good internal consistency of α > 0.84. Each item was rated on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 (1 = “really true”, 2 = “sort of true”, 3 = “in the middle”, 4 = “not really true”, and 5 = “not at all true”). A model with a parent–child relationship quality factor with loadings on the SIQYA Family Relationships Scale assessed at each year and auto-residual correlations such that items in closer temporal proximity were more highly correlated fit the data well, with significant factor loadings on each item, χ2(112) = 148.273, p = 0.012, RMSEA = 0.043, CFI = 0.967. There was evidence for scalar measurement invariance across all groups, Δχ2(18) = 24.873, p = 0.128 (cf. metric vs. scalar), Δχ2(6) = 13.883, p = 0.031 (cf. scalar vs. residual).

Adoption satisfaction

Adoptee-reported satisfaction was assessed with adoptee self-report on two scales, when adoptees were between ages 16 and 19, with most individuals assessed at age 17 (see Table S6 for descriptive statistics). One scale consisted of 12 items assessing acceptance of adoption status and the other consisted of six items assessing security in belonging to an adoptive family (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, McGue and Benson1998). Acceptance items included questions such as “I wish people did not know I was adopted,” and prior studies have confirmed good internal consistency (α = 0.83) (Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rhee, Corley, Rhea, Wadsworth and DeFries2011). Security items included questions such as “I think my parent(s) would love me more if I were their birth child,” and had good internal consistency (α = 0.78). High acceptance scores indicated high acceptance of adoption status and high security indicated high security within the family. Values were subtracted from the highest variable value and log transformed due to negative skew.

Adoptive parents completed a parent version of this questionnaire including two scales (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, McGue and Benson1998). The first scale assessed how well parents believed their adopted child was integrated into the family with three items. The next scale assessed how different they believed their family situation was in comparison to nonadoptive families with 14 items. Integration was assessed with questions such as “I usually donʼt think of my child as having been adopted,” with a prior reported internal consistency of α = 0.64 (Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rhee, Corley, Rhea, Wadsworth and DeFries2011). Difference was assessed with questions such as “I introduce my child to others as an adopted child,” with an internal consistency of α = 0.85 (Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rhee, Corley, Rhea, Wadsworth and DeFries2011). Higher integration scores indicated parents believed the adopted child was not well integrated into the family. Higher difference scores indicated parents believed adoptive families are different from nonadoptive families. Integration was transformed by an inverse due to negative skew. See Table S6 for descriptive statistics.

Orientation to Parents in Adolescence

Agreement between parents and friends and influence of parents

The Orientation to Parents Index (Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Turbin and Costa1998), a self-report measure completed by adolescents at age 17 (M = 16.91, SD = 0.58), is comprised of the agreement scale, which measures perceived agreement on values between the participant’s parents and friends (α > 0.76), and the influence scale, which measures the relative communication between parents and friends about the subject’s behavior, choices, and perspectives (α > 0.62; Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Turbin and Costa1998). Both scales were comprised of ordinal answer options coded numerically from 1 to 3 (1 = “no,” 2 = “a little,” and 3 = “a lot” and 1 = “friends most,” 2 = “parents and friends the same,” and 3 = “parents most”, respectively; see Table S5 for frequencies). Agreement items included questions such as, “Would your friends agree with your parents (or the main adults in your life) about the kind of person you should become?”. Influence items consisted of questions such as, “If you had to make a serious decision about school or work, who would you depend on most for advice: your friends or your parents?”.

EFA results confirmed the evidence for a two-factor model including all original items in the measure (see Table S8). CFA indicated good model fit and significant factor loadings for all items (see Figure S6) and evidence for measurement invariance across groups, Δχ2(24) = 25.482, p = 0.380 (cf. noninvariant vs. invariant5). Correlations between the “Agreement” and “Influence” factors were significant in all groups except in nonadopted boys (p = 0.098).

Parent SES

Parent SES was included as a covariate in these analyses due to evidence of associations between familial SES and adolescent substance use (Lemstra et al., Reference Lemstra, Bennett, Neudorf, Kunst, Nannapaneni, Warren, Kershaw and Scott2008; Patrick et al., Reference Patrick, Wightman, Schoeni and Schulenberg2012; Stone et al., Reference Stone, Becker, Huber and Catalano2012).2 For adoptive and nonadoptive parents, three assessments of parent SES were used: maternal educational attainment in years (M = 14.80, SD = 15.66), paternal educational attainment in years (M = 15.66, SD = 2.33), and father’s occupational attainment (M = 51.20, SD = 12.49; based on the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) occupational rating scale). Only paternal occupational status was examined given the limited number of mothers working outside of the home during the era in which the study was initiated. SES variables were collected upon entering the study. A composite SES variable was created using the mean of z-scores for maternal education, paternal education, and father’s occupational attainment.

Pubertal timing

Adopted girls, compared to nonadopted girls, exhibit earlier pubertal development (Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Berenbaum, Bricker, Corley and Wadsworth2012). There are also significant associations between pubertal timing and externalizing behaviors (Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014), which are associated with substance use. Thus, we examined age of puberty as a covariate. Pubertal timing was assessed annually from Grade 3 (M = 9.47, SD = 0.37) to the end of Grade 9 (M = 15.37, SD = 0.32) with the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Hawkins, Abbott and Catalano1994). Participants reported on five questions about development of secondary sexual characteristics, including menarche in girls, facial hair and deepening voice in boys, and growth spurt as well as skin, hair, and body changes in both sexes. The scale was comprised of options coded numerically from 1 to 4 (1 = “no development”, 2 = “yes, barely”, 3 = “yes, definitely”, and 4 = “development completed”). Menarche was coded as either 1 or 4 (1 = “absent”, 4 = “completed”). A summary PDS score for each age was produced by averaging item scores. Pubertal timing was calculated previously by Beltz et al. (Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014) and estimated from group trajectories of development, calculated separately by sex. Pubertal timing was defined as peak change rate at the midpoint of puberty (PDS score of 2.5 corresponding to Tanner stage 3; Beltz et al., Reference Beltz, Corley, Bricker, Wadsworth and Berenbaum2014).

Adolescent substance use

Adolescent substance use was measured with questions from the Monitoring the Future Survey (MTF; Johnston & O’Malley, Reference Johnston and O’Malley1986). Responses were collected at age 17 (M = 17.11, SD = 0.45). We selected this measure of adolescent substance use because it was the first comprehensive assessment of adolescent substance use in our sample and adolescent substance use is typically initiated by age 17 (Schulenberg et al., Reference Schulenberg, Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, Miech and Patrick2020). This evaluation occurred while the adolescents were still living at home with their parents, as the influence of the parenting is the focus of this study. Participants reported on frequency of tobacco, marijuana, alcohol, and other illegal substance use (e.g., narcotics, heroin, and tranquilizers). Frequency questions addressed use in the past 30 days, past 12 months, and throughout the respondent’s lifetime, with the question “How many times have you used [substance] during [time period]?”. For most substances, participants provided a number that reflected number of times used. For tobacco use, participants reported on their pattern of use with the question “Have you ever used cigarettes?” (0 = “never”, 1 = “once or twice”, 2 = “occasionally, but not regularly”, 3 = “regularly in the past”, 4 = “regularly now”). Past 30-day cigarette use was captured with the question “How many times have you used cigarettes in the past 30 days?” (0 = “none,” 1 = “less than once per day,” 2 = “one to five cigarettes per day,” 3 = “about one half pack per day,” 4 = “about one pack per day,” 5 = “about one and one-half packs per day,” 6 = “two packs or more per day”). Due to low rates of reported other illegal drug use, an illegal drug use score was compiled by using the highest frequency score across illegal drug categories for each frequency item (see Table S3 for frequencies).

All substance use scores were collapsed into ordinal variables that maximized variability while limiting small cell sizes (see Table S3). Analyzing non-normally distributed variables as ordinal variables assuming an underlying continuous normal liability distribution reduces bias in the estimates (Derks et al., Reference Derks, Dolan and Boomsma2004). In congruence with prior evidence supporting a general substance use model for adolescent use (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Young, Hopfer, Corley, Stallings, Crowley and Hewitt2009; Zellers et al., Reference Zellers, Iacono, McGue and Vrieze2021), a model with a hierarchical substance use factor with loadings on latent factors for marijuana, alcohol, cigarette, and other illegal drug use fit the data well, with significant factor loadings for all items (see Figure S5). When correlations between two items of the same drug class were too highly correlated to account for unique variance in the latent substance use factor, one item of the two was used. There was measurement invariance across all four groups, Δχ2(120) = 118.249, p = 0.528 (cf. noninvariant vs. invariant5).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using MPlus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). Structural equation models examined correlations between predictors (parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents) and adolescent substance use, using the best-fitting models from CFAs examining each measure.Footnote 6 We examined whether associations remained significant after controlling for SES, pubertal timing, and adoption satisfaction. Associations were initially evaluated separately by family type (nonadoptive and adoptive) and sex. Any significant correlations between predictors and outcomes in adoptive families provided evidence for environmental effects.

After evaluating associations separately by group, statistically significant correlations with adolescent substance use in at least one group were tested for sex and adoptive/nonadoptive differences. Original models with correlations freed were compared to models equating correlations across groups (i.e., correlations were equated for adopted and nonadopted boys, and adopted and nonadopted girls), using a χ2 difference test. Results would be consistent with passive rGE if correlations were significantly higher in nonadoptive families than adoptive families. For significant putative environmental predictors (i.e., parenting characteristics) of adolescent substance use, we also conducted post hoc analyses examining the potential influence of evocative rGE by comparing the correlations for the putative environmental predictors in adoptive (genetically unrelated) and nonadoptive (genetically related) sibling pairs. Models with freed correlations were compared to models equating correlations across groups to test for group differences using a χ2 difference test. Significant differences in correlations between adoptive and nonadoptive siblings, with significantly higher correlations in nonadoptive siblings, would indicate the influence of evocative rGE on predictors.

Additional post hoc analyses evaluated whether associations between early positive parenting influenced adolescent substance use indirectly via parent–child relationship quality.Footnote 7 We used the MODEL INDIRECT command in MPlus to calculate direct and indirect effects. We implemented bootstrapping with replacement for 1000 samples, a method for meditation testing that repeatedly samples the data, empirically approximates the sampling distribution, and allows estimation of asymmetrical confidence intervals (Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008).

In all analyses, to address nonindependence of data from participants in the same family, the TYPE = COMPLEX option was used to compute corrected standard errors and scaled chi-squares with a sandwich estimator. We used WLSMV estimation method with pairwise deletion for analyses including ordinal data and used MLR for analyses using only continuous data. To address multiple significance testing, we used the FDR controlling method, which is more powerful than the Bonferroni method or family-wise error rate (Benjamini & Hochberg, Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995)

Results

Correlations between predictors and adolescent substance use

Parenting measures and adolescent substance use

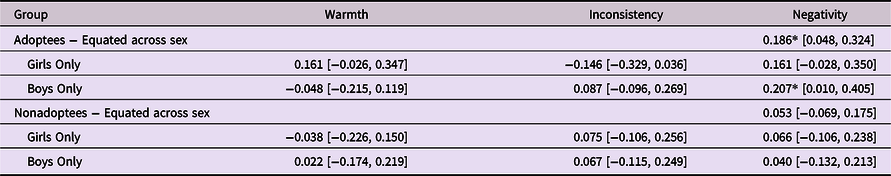

Correlations between the Caldwell HOME Scale and adolescent substance use were not significant (see Table 1). In addition, Dibble and Cohen Warm and Inconsistent Parenting were not significantly associated with adolescent substance use (see Table 2). Negative parenting was not significantly associated with adolescent substance use in most groups (see Table 2), and there were no significant differences in correlations by sex, Δχ2(2) =0.153, p = 0.927.Footnote 8 When correlations between negative parenting and adolescent substance use were equated within adoption status (e.g., correlations in adopted girls equal to correlations in adopted boys), correlations were significant for adoptees but not for nonadoptees. However, differences in correlation by adoption status were not significant, Δχ2(2) = 2.021, p = 0.364. These results suggest that parenting did not consistently predict adolescent substance use.

Table 1. Correlations between substance use and early positive parenting (N = 841)

Note. Higher positive parenting scores (measured by the Caldwell HOME Scale) indicate higher positive parenting. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

No p values < 0.05

Table 2. Correlations between substance use and parenting domains in later childhood through adolescence (N = 784)

Note. Higher warmth, inconsistency, and negative parenting scores (measured by the Dibble and Cohen Parent Report) indicate greater warmth, inconsistent, and negative parenting respectively. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

*p < .05. No FDR adjusted p < .05.

Parent–child relationship quality and adolescent substance use

Parent–child relationship quality in later childhood through adolescence

Parent–child relationship quality in later childhood through adolescence, measured by the SIQYA Family Relationships Scale, was significantly, negatively associated with adolescent substance use in all groups except for adopted girls (See Table 3).Footnote 9 There were no significant differences by sex, Δχ2(2) = 2.098, p = 0.350 or adoption status Δχ2(2) = 1.509, p = 0.470. When equated by group, correlations for both adoptees and nonadoptees were significant.

Table 3. Correlations between substance use and parent–child relationship quality

Note. Higher parent–child relationship quality in later childhood to adolescence (measured by the Self-Image Questionnaire for Young Adolescents; SIQYA) indicates greater parent–child relationship quality. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

***p ≤ 0.001. ʃ FDR-adjusted p-values < 0.05.

Adoption satisfaction

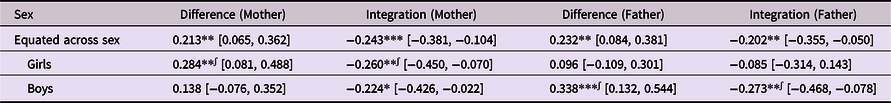

In both girls and boys, correlations between adoptee-reported acceptance and adolescent substance use were significant, suggesting that adoptees with higher perceived acceptance have lower frequencies of substance use, with no significant sex differences, Δχ2(1) = 0.061, p = 0.805 (See Table 4). Correlations were not significant for the security domain (See Table 4). Correlations between mother-reported difference (e.g., perceived differences between adoptive and nonadoptive families) and adolescent substance use were significant in adopted girls (See Table 5). When collapsed across sex, correlations were significant. Correlations with mother-reported integration were significant in both groups. Higher perceived differences and lower perceived integration were associated with higher rates of adoptee substance use. No sex differences were found for the difference Δχ2(1) = 0.939, p = 0.333 or integration, Δχ2(1) = 0.062, p = 0.804. Father-reported differences and integration followed a similar pattern, such that higher perceived differences and lower perceived integration were associated with higher rates of substance use in adopted boys. No sex differences were found for father-reported difference, Δχ2(1) = 2.651, p = 0.104, and integration, Δχ2(1) = 1.518, p = 0.218, correlations. When equated across sex, both father-reported difference and integration were significant. Higher parent-reported adoption satisfaction by parents of the same sex as the child were associated with lower levels of substance use (See Table 5). All significant associations remained significant after controlling for pubertal timing and parent SES, except for the correlation between adoptee-reported acceptance and adolescent substance use in adopted girls (Tables S11 and S12). These associations suggest that higher adoption satisfaction, reported by both parents and adolescents, is a consistently significant predictor of lower adolescent substance use.

Table 4. Correlations between substance use and adoption satisfaction domains, adolescent self-report (N = 308)

Note. Higher acceptance and security scores indicate lower adoption satisfaction. Higher difference and lower integration scores indicate lower adoption satisfaction. To control for pubertal timing in adopted girls, adolescent substance use was measured using lifetime use indicators for other drugs, due to limited cell sizes (correlations between predictors and adolescent substance use were consistent with those using a hierarchical factor). The hierarchical substance use variable was used for adopted boys. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ʃFDR adjusted p < 0.05.

Table 5. Correlations between substance use and adoption satisfaction domains, parent self-report (N = 301-305)

Note. Higher acceptance and security scores indicate lower adoption satisfaction. Higher difference and lower integration scores indicate lower adoption satisfaction. To control for pubertal timing in adopted girls, adolescent substance use was measured using lifetime use indicators for other drugs, due to limited cell sizes (correlations between predictors and adolescent substance use were consistent with those using a hierarchical factor). The hierarchical substance use variable was used for adopted boys. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ʃFDR adjusted p < 0.05.

Orientation to parents in adolescence and adolescent substance use

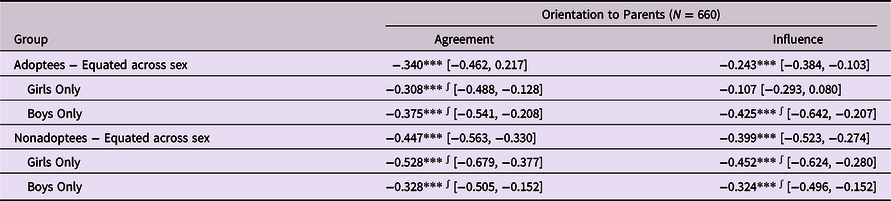

For orientation to parents assessed in adolescence, correlations between the agreement factor and adolescent substance use were negative and significant in all groups (See Table 6). Higher agreement between parents and friends was associated with lower adolescent substance use. There were no differences by sex, Δχ2(2) = 2.813, p = 0.245, or adoption status Δχ2(2) = 3.403, p = 0.182. Both adoptee and nonadoptee correlations were significant.

Table 6. Correlations between substance use and orientation to parents in adolescence

Note. Higher orientation to parents (measured by the Orientation to Parents Index) indicates greater parent–child relationship quality. If correlations were significant for either or both sex, results from the model where correlations are equated across sex are also shown.

***p ≤ 0.001. ʃ FDR-adjusted p-values < 0.05.

In most groups, correlations between the influence factor and adolescent substance use were significant (higher influence of parents was correlated with lower rates of substance use). Correlations were not significantly different across sex but were higher in boys, Δχ2(2) = 5.740, p = 0.057, and significantly higher in nonadoptees, Δχ2(2) = 10.189, p = 0.017 (See Table 3). When tested separately by sex, differences between adoptees and nonadoptees were significant for girls, Δχ2(2) = 9.986, p = 0.007,Footnote 10 but not boys Δχ2(1) = 1.003, p = 0.317. Moreover, in nonadoptees, correlations between the agreement and influence factors were independent predictors of adolescent substance use after controlling for parental SES and pubertal timing. However, in adopted girls, after controlling for parent-reported adoption satisfaction (mother-reported differences and integration, father-reported differences and integration), pubertal timing, and parent SES, associations between the agreement factor and adolescent substance use were no longer significant (Table S9). In adopted boys, the correlations between the agreement factor and adolescent substance use were no longer significant after controlling for mother-reported differences and integration, pubertal timing, and parent SES (Table S9).

Post hoc analyses and results

We conducted post hoc analyses to address the variability in results across parenting measures. There was little evidence that observer-rated parenting during toddlerhood or parent-rated parenting during childhood predicted adolescent substance use. Significant predictors (i.e., parent–child relationship quality) were typically more proximal to the assessment of adolescent substance use than the non-significant predictors. Although the Dibble and Cohen Parent Report was administered during the same time as the SIQYA Family Relationships Scale, it utilized parent report. Except for parent-reported adoption satisfaction, significant predictors were assessed using adolescent self-report, which raised the possibility that significant associations between adolescent self-report of parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents and substance use were due to method covariance or common rater bias. In addition, we were concerned that lack of construct validity of the Caldwell HOME Scale (i.e., that this observer-reported measure did not effectively measure positive parenting) may have led to nonsignificant associations between early positive parenting and adolescent substance use. Relatedly, we considered the possibility that warm, inconsistent, and negative parenting in later childhood through adolescence were not associated with adolescent substance use given the lack of validity of the Dibble and Cohen Parent Report.

To address these issues, we examined the correlations between all parenting characteristics. Although the patterns of correlations were not consistent (Tables S13 and S14), there were several significant correlations between early positive parenting, parenting in later childhood and adolescence, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents, providing additional evidence of construct validity of all parenting measures. Also, the pattern of correlations between predictors prompted us to examine whether early positive parenting influenced adolescent substance use indirectly via parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents (via the SIQYA measured from ages 9–15 and the agreement factor measured at age 17). Indirect effects via parent–child relationship quality were significant in adopted and nonadopted boys (Table S15). Indirect effects via the agreement factor were significant only in nonadopted boys (Table S16). These results provide suggestive evidence that early positive parenting influenced adolescent substance use indirectly via parent-child relationship quality and orientation to parents, specifically in boys.

Evaluation of evocative rGE

Next, we compared the correlations for parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents (i.e., the significant predictors of adolescent substance use) in adoptive and nonadoptive sibling pairs. All sibling correlations were positive. Correlations between nonadoptive sibling pairs for the agreement factor and SIQYA Family Relationships Scale were significant, whereas correlations between adoptive sibling pairs were significant for the influence factor. None of the correlations were significantly different across adoptive and nonadoptive sibling pairs (Table S17), suggesting lack of evidence for evocative rGE.Footnote 11

Discussion

Hypothesis I: Predictors of adolescent substance use

The present study utilized a prospective adoption study to examine parental influences on adolescent substance use. Contrary to our hypotheses, results suggested that, in general, parenting measures assessed in toddlerhood (observer-reported) and from childhood to adolescence (parent-reported) were not significantly correlated with adolescent substance use. These nonsignificant associations contrast with findings from prior studies (Brook et al., Reference Brook, Rubenstone, Zhang and Brook2012; Dishion & Reid, Reference Dishion and Reid1988; Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Horwood and Ridder2005; Kaplow et al., Reference Kaplow, Curran and Dodge2002; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017; Vicary & Lerner, Reference Vicary and Lerner1986) that suggest positive and negative parenting influence adolescent substance use. One possible source of these inconsistencies may be differences in the operationalization of parenting and assessment methods used.

In congruence with our hypothesis, parent–child relationship quality in later childhood through adolescence (measured by the SIQYA Family Relationships Scale) was significantly, negatively associated with adolescent substance use. In addition, orientation to parents (agreement between and influence of parents versus friends) was also significantly, negatively associated with adolescent substance use. These results indicate that perceived agreement of values across parents and friends, greater communication with parents, and stronger bonds with parents across life domains resulted in less adolescent substance use. Our findings align with prior research finding that greater communication and bonding between parents and adolescents is protective against substance use and delinquent behaviors (Kapetanovic et al., Reference Kapetanovic, Skoog, Bohlin and Gerdner2019; Keijsers et al., Reference Keijsers, Branje, VanderValk and Meeus2010). In addition, more agreement in values across parents and friends may also indicate that parents socialize their adolescents into developing friendships that align with more normative values (Jessor et al., Reference Jessor, Turbin and Costa1998).

Parent-reported adoption satisfaction was generally negatively associated with adolescent substance use for children of the same sex as their parent (e.g., father-reported adoption satisfaction was significantly correlated with adoptee substance use in boys). Adoptee-reported acceptance was also significantly, negatively associated with adolescent substance use. Results remained significant after correcting for multiple testing, except for adoptee-reported acceptance in boys. Our findings are supported by prior research indicating that decreased adoption satisfaction and family compatibility is associated with increased conduct problems (Grotevant et al., Reference Grotevant, Wrobel, van Dulmen and Mcroy2001; Nilsson et al., Reference Nilsson, Rhee, Corley, Rhea, Wadsworth and DeFries2011). Overall, these findings align with previous research, which has found negative associations between parent–child relationship quality and adolescent substance use (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Hops and Duncan1997; Drapela & Mosher, Reference Drapela and Mosher2007; Foshee & Bauman, Reference Foshee and Bauman1992). We found no evidence for sex differences in associations between these predictors and outcomes.

Notably, after controlling for covariates in adopted girls, correlations between adoptee-reported acceptance and the agreement factor and adolescent substance use were no longer significant. Prior research has demonstrated that, in this sample, pubertal timing is significantly earlier in adopted girls than nonadopted girls (Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Berenbaum, Bricker, Corley and Wadsworth2012). Earlier pubertal timing has been associated with decreased parent–child relationship quality and aspects of orientation to parents (e.g., open communication), in addition to greater frequency of adolescent substance use (Dick et al., Reference Dick, Rose, Viken and Kaprio2000; Hummel et al., Reference Hummel, Shelton, Heron, Moore and van den Bree2013; Stojković, Reference Stojković2013). In the present study, orientation to parents in adolescence did not predict any additional variance in adolescent substance use after accounting for pubertal timing in adopted girls.

Hypothesis II: The role of passive rGE versus environmental mediation in associations between predictors and adolescent substance use

The genetically informed, longitudinal adoption design allowed us to evaluate differences in associations between adoptive and nonadoptive families and examine whether associations are due to passive rGE or environmental mediation. Environmental mediation best explained almost all significant associations between parenting and adolescent substance use, as the correlations in adoptive and nonadoptive families were similar in magnitude and not significantly different. One deviation from this pattern occurred in girls only, with a greater correlation between the influence factor assessed in adolescence and adolescent substance in nonadoptive families versus adoptive families. This was the only association with any evidence for passive rGE. These results indicate that the environment is a more consistent influence on the significant associations between parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents and adolescent substance use, although a lack of power may have restricted our ability to detect more subtle differences across groups. We found no significant evidence of the role of evocative rGE on these associations in exploratory analyses, suggesting that genetic predisposition of children did not evoke better parent–child relationship quality or greater orientation to parents. Our findings suggest that interventions focusing on strengthening bonds between parents and children may be promising in preventing adolescent substance use.

Post hoc findings

Post hoc analyses were conducted to address the variability in results across parenting characteristics, particularly the nonsignificant prediction of adolescent substance use by measures of parenting assessed by observers and parents. There were several significant correlations between observer-rated early positive parenting, parent-reported parenting in later childhood and adolescence, child- and adolescent-reported relationship quality, and adolescent-reported orientation to parents, providing additional evidence of construct validity of these measures. These post hoc findings, along with significant associations between parent-reported adoption satisfaction and adolescent substance use, suggest that it is unlikely that significant associations between parenting and substance use reported in the present study are simply due to method covariance or common rater bias. A more likely explanation is that more proximal assessments are more robust predictors of adolescent substance use. In addition, results from mediation analyses provided preliminary evidence that in boys, earlier positive parenting may influence adolescent substance use indirectly by increasing parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents (i.e., better communication, more positive views of parents), which in turn is protective against adolescent substance use. Notably, these results align with prior research suggesting that maternal warmth is associated with more honest parent–adolescent communication, which leads to lower rates of underage drinking (Lushin et al., Reference Lushin, Jaccard and Kaploun2017).

Study strengths, limitations, and conclusions

The present study had several strengths. It examined associations between adolescent substance use and parenting, parent–child relationship quality, and orientation to parents in a prospective, longitudinal, genetically informed study. The prospective, longitudinal design of this study of is less biased than retrospective designs, which are more vulnerable to recall bias (Hardt & Rutter, Reference Hardt and Rutter2004; Nivison et al., Reference Nivison, Vandell, Booth-LaForce and Roisman2021). The sample consisted of matched adoptive and nonadoptive families with minimal confounding variables (e.g., familial SES). This design allowed us to investigate the influence of environment versus passive rGE on associations between predictors and outcomes. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses demonstrated that all the putative environmental variables assessed from early childhood to adolescence were reliable and valid.

The results should be interpreted with consideration to the limitations of this study. First, we had intended to explore parental substance use in infancy as a predictor of adolescent substance use, based on prior findings that parental alcohol (Dishion & Reid, Reference Dishion and Reid1988; Kaplow et al., Reference Kaplow, Curran and Dodge2002; Tildesley & Andrews, Reference Tildesley and Andrews2008), cigarette (Brook et al., Reference Brook, Rubenstone, Zhang and Brook2012; Staff et al., Reference Staff, Maggs, Ploubidis and Bonell2018), and other drug use (Dishion & Reid, Reference Dishion and Reid1988; Fergusson et al., Reference Fergusson, Boden and Horwood2008) in early childhood are associated with their children’s substance use in adolescence. However, we had a very limited measure of parental substance use for adoptive parents of adoptees and biological parents of nonadoptees that consisted of one assessment of alcohol use frequency before children were 1 year old (see Table S19 for frequencies and Figure S7 for CFA results and see Table S20 for correlations between parental and adolescent substance use).

In addition, our adolescent sample did not exhibit extensive illegal substance use because it was ascertained from the community rather than a clinical setting; 23.5% of the sample met DSM-IV Dependence criteria for at least one substance. Illegal substance use was measured with a latent factor capturing highest use across illegal drug classes for each frequency question. Other illegal use in the past 30 days was limited to two categories, use versus no use. Ethnic and racial diversity was also limited, as most participants were Non-Hispanic White. Though many aspects of parenting were assessed throughout development, there was not an assessment of other parenting dimensions consistently associated with substance use (e.g., monitoring; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Catalano and Miller1992). Also, we lacked assessments of parenting characteristics in years after adolescent substance use, which would have allowed us to evaluate the possibility of reverse causation (i.e., adolescent substance use influencing parenting). Lastly, our sample was recruited between 1975 and 1983. The longitudinal design of this study is a strength, but normative patterns of substance use (particularly in the context of legalization), parenting practices, and parent–child relationship quality may have changed throughout the years.

Of note, the aim of this study was to disentangle the role of passive gene–environment correlations versus environmental mediation in the association between parenting characteristics and adolescent substance use using an adoption design, and evidence from the present study is more consistent with environmental mediation. However, parents may influence children via shared or nonshared environmental mediation (influences that make siblings more or less similar, respectively; Turkheimer & Waldron, Reference Turkheimer and Waldron2000). Sibling correlations for parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents were positive and not significantly different across adoption status but far from 1.0, suggesting the possibility that parents influence children via either shared or nonshared environmental mediation.

In conclusion, observer-reported parenting measures collected in toddlerhood and parent-reported parenting measures collected from childhood to adolescence were not significantly correlated with adolescent substance use, whereas several measures of parent–child relationship quality and orientation to parents, including perceptions of family relationships, perceived agreement between parents and friends in adolescence, and perceived influence of parents in adolescence were robust predictors of adolescent substance use. These associations were better explained by the environment, as opposed to passive rGE (i.e., a genetic predisposition towards both familial dysfunction and adolescent substance use) or evocative rGE (i.e., genetic predisposition towards substance use evoked specific parent behaviors). Significant predictors were proximal to measures of adolescent substance use. These results increase our understanding of the mechanisms through which parenting influences adolescent substance use and suggests useful targets for effective intervention. Notably, these results are aligned with intervention studies finding that family-based interventions focused on relationship quality are effective in preventing adolescent problem behaviors, including substance use (Dishion & Mauricio, Reference Dishion and Mauricio2015; Kumpfer & Magalhães, Reference Kumpfer and Magalhães2018; Kuntsche & Kuntsche, Reference Kuntsche and Kuntsche2016).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579422000748

Data analyzed in this study are available by emailing the corresponding author, except where participant directives do not permit us to do so. Requests for data require completion of a data use agreement, documentation of training on the protection of human subjects, and the purpose of use. Analysis code is available by emailing the corresponding author. This study’s design, hypothesis, and analysis plan were preregistered through Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/8msvh/).

Funding statement

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HD010333, DA035804, DA011015, and AG046938.

Conflicts of interest

None.