Preamble

This article contributes to a local and transnational, critical history of Greek modern dance, centering on choreographer and dancer Vassos Kanellos. Born Vassileios Kanelopoulos in the Peloponnese, Kanellos (1895?–1985) developed a career spanning at least twenty years, in collaboration with his wife, Tanagra, and after her death, their daughter, Xenea. His theatrically oriented dance practice combined skillful (e.g., virtuosic high jumps) and simple (e.g., solemn marches) motions, balanced lines, plasticity, and rhythmicality (cf. Kanellos Reference Kanellos1966, 43, 55–56). A multitude of sources on Kanellos remain—photographs, texts, performance programs, press clippings—mainly held at the Literary and Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA [Eliniko Logotehniko ke Istoriko Arhio]).Footnote 1 Nevertheless, Kanellos has largely been written out of history: practically absent from non-Greek scholarshipFootnote 2 and relatively little known within the country (for a short account, see Fessa-Emmanouil Reference Fessa-Emmanouil2004, 218–221). Kanellos's marginalization mirrors the wider dance-historiographic marginalization of Greece, assumed to be part of Western dance history even though its local dance production remains severely underrepresented.

Narratives of dance modernity still focus primarily on Western Europe and the United States, amalgamating them into a universalized canon anchored in the “West”—a historical, cultural, and political construct rather than a geographical denominator—that peripheralizes other dance histories. The very concept of dance modernity (roughly from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth) is a classification of Western dance historiography. Non-Western dance histories have been, and largely continue to be, systematically excluded and/or portrayed through exotifying West-defined concepts. The West-defined canon does not even fully account for the heterogeneity present within the “West,” a point that is made evident regarding Greece. Greece is considered an integral part of Western dance history, but Greek perspectives on this history and Greece-based artists remain unknown. When appearing in historiographic accounts of dance modernity, Greece is mostly associated with performances of antiquity, primarily staged by non-Greek artists. A lack of knowledge persists regarding how Greek dancers and/or foreign artists working there also wrote the narrative of Greek dance in modernity. Scholarship is limited within the country, too, while published work remains widely unacknowledged abroad. The marginalization of this history is acutely relevant, with Greek contemporary dance hovering on the verge of mainstream recognition.

The ambivalent Greek presence in dance modernity is part of the country's complex relationship with Western Europe. Greece's past is foundational in the narrative of origin of the “imaginary entity” (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty1992, 21) of Europe, but Greece's present is only partly acknowledged as part of the modern(ized) West. Modern Greece is perceived by Western Europe as both exotic and European: neither fully European nor fully Other (cf. Herzfeld [1987] Reference Herzfeld1989, 1–2). Contrary to the Global South, Greece enjoys privileges resulting from its inclusion in the European construct: financial and political, but also in the form of ancient Greece's inclusion in Eurocentric culture. At the same time, such privileges are limited by modern Greece's subaltern status within the European construct. Again, this concerns economic and political realms (e.g., how Greece was allowed to sink into a deep financial and humanitarian crisis in the late 2000s) as well as art, evidenced by the lack of representation of post-antique Greek culture at a European level.

It is to reflect this situation that I use, throughout this text, the term “Western/Europe(ean).” Rather than claiming their interchangeability, the association of the two words draws attention to the centrality of Europe in constructing the “West” and the unquestioned conception of Europe as Western. The slash between them ruptures this conflation as a reminder that not all parts of Europe are equally admitted as “Western”: Greece is in the interstitial space of a “European Other” (the term is drawn from El-Tayeb Reference El-Tayeb2011). This positionality also colors the terms “Orientalized”/“Orientalization” in this article, which slightly differs from their use as references to perceptions and representations of an “East” constructed by a patronizing, Othering Western worldview. The West considers Greece as part of its own history and identity, but the Byzantine and Ottoman periods of Greece's history, and their traces in modern Greece, are also related to Orientalized regions and cultures and subject to Orientalization themselves. Greece's inclusion in the West depends upon the active dismissal of those parts of its history that are Orientalizable. External perceptions of Greece, as well as internal experiences of Greek identity, reflect such ambivalences that were embodied, performed, and staged by Vassos Kanellos.

This article calls Kanellos out of the archive to illuminate how dance has been employed to navigate this interstice, creating what Ana Vujanović, drawing on Walter Benjamin, calls “a critical illumination of those aspects of the past that were invisible then and are still not visible from the perspective of the globally predominant historiciazation of dance” (Reference Vujanović2008). I examine Kanellos as a figure that navigated the peripheralization of “Greek” dance, negotiating its performance in relation and in opposition to Western visions of it. I argue that he oscillated between proximity—aesthetic, technical, and stylistic similarities with Western/European dance modernity—and differenceFootnote 3—reappropriating “Greek” dance by embodying Orientalized aspects of Greekness. His example makes manifest the complex domestic and international dynamics that shaped Greek dance modernity's performance of its own Greekness.

Context, Framework, and Directions

In the early twentieth century, Western/European projections on modern Greece, haunted by an overbearing antiquity and Orientalized as a part of the former Ottoman empire, combined with volatile political circumstances domestically. In a period abandoning the heterogeneous ethnic fabric of empires toward the territorially bound, ethnically homogeneous national model, Greece's borders oscillated. In the 1910s, it integrated a large proportion of territory from the Ottoman Empire; it also, traumatically, lost its brief access to Asia Minor territories in a devastating military defeat in 1922. Large Greek-defining communities lived outside the country, either as immigrants or in ex-Ottoman Balkan/Asia Minor regions, disconnecting the geopolitically defined space of Greece and the subjective experience of identifying as Greek. Irredentist visions were prominent, notably the so-called Great Idea (Megali Idea, literally “big” idea) according to which Greece was to expand its national borders to attain regions that belonged to the Byzantine Empire after centuries of what was perceived as Ottoman occupation. By 1936, Greece was caught in the nationalist military dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas. Internal needs, such as homogenizing a culturally and linguistically diverse ex-Ottoman population, and external imperatives of presenting the country to foreigners, created parallel forces of introversion and extroversion in Greek national identity (cf. Savrami Reference Savrami2019, 15).

This situation translated in modern dance through a strong focus on the nation: dance represented, embodied, and performed its particularity as Greek. This intensive choreographic focus is, to an extent, relevant today: contemporary dance in Greece has complex relationships with a dominant ideal of the nation (e.g., Tzartzani Reference Tzartzani2007); figures with a strong nation-bound tendency are still more represented in Greek dance history. Unpacking the historical essentialization of the nation in Greek dance is therefore crucial for the contemporary landscape as well. Vassos Kanellos, whose entire oeuvre revolved around Greekness, is a key figure through whom the essentialization of national identity, as well as foreign influences upon it, can be identified and critically deconstructed.

Exploring Kanellos's “Greek” dance entails not only looking at works by a Greek choreographer but also, crucially, at dance that performatively enacts and reconstructs Greek national identity. Political theory and philosophy have provided multiple concepts presenting the nation as a constructed and therefore contingent ideation: an imagination (e.g., Anderson [1983] Reference Anderson2006) or a fiction (e.g., Balibar Reference Balibar, Balibar and Wallerstein1991, 96). James D. Faubion (Reference Faubion1993, xii) sees “historical constructivism” as the hallmark of modern Greekness, whereas Stathis Gourgouris (Reference Gourgouris1996) analyzes the Greek nation through the metaphor of a dream. Although discourse—words and acts of naming—is paramount in the process of constructing the nation, bodies experience and enact national narratives too. Bodily action confirms and reinforces national fictions through sensed and affective experiences, potentially boosting anti-constructivist, essentialist perceptions of the nation as “authentic.” Dance can correspondingly feed (and has fed) into nationalist ideals. Against this background, this text's references to dancing Greekness are multilayered. First, I refer to performing the nation on the dance stage, in works classified as art, underlining the choreographic realm's role in forming national idea(l)s. Second, I refer to a performance of the nation as a specifically bodily act, in line with what Rachel Fensham (Reference Fensham, Carter and Fensham2011, 11) has called an “embodied theorization of modernity,” underlining its incarnated dimension. Finally, I refer to performing the nation in a Butlerian sense: as actions whose (repeated) accomplishment brings about and reproduces national identity.

Dance scholarship in and about Greece increasingly recognizes the constructed-ness of the nation and the contribution of choreography to it.Footnote 4 This article provides a contribution to such scholarship by reading Greek modern dance's preoccupation with the nation in its negotiation with domestic and foreign expectations. Kanellos is a particularly relevant case study in this respect, as his relative marginalization in Greek dance history correlates with his particular treatment of national identity. Kanellos followed canonical tropes of performing Greekness but also engaged with choreographically disregarded aspects of that identity. He engaged in multiple exchanges with Western/Europe while significantly deviating from foreign expectations. Focusing on Kanellos therefore diversifies the canon of Greek dance history, against the homogenization that peripheralized dance histories tend to be reduced to, adding complexity to our understanding of the repertoire of strategies Greek artists used to respond to both internal and external pressures.

I place my discussion of Greek dance in the context of new modernist studies and its intersections with critical dance studies (cf. Burt and Huxley Reference Burt and Huxley2020; Preston Reference Preston2014). New modernist studies constitute a methodological framework for approaching modernism that was initiated in the field of literature, notably through Douglas Mao and Rebecca Walkowitz's 2008 article, “The New Modernist Studies.” Mao and Walkowitz (Reference Mao and Walkowitz2008, 737–738) urged a move toward a “spatial” expansion of the analysis of modernism, to avoid its Western/European bias; and a “vertical” expansion opening toward the modernity enacted by groups excluded from the canon. This is consistent with dance studies’ increasing focus on hitherto unacknowledged practices, agents, and contexts (e.g., Wittrock Reference Wittrock2020, Reference Wittrock and Folkwang2021; Haitzinger Reference Haitzinger, Hausbacher, Herbst, Ostwald and Thiele2020). It is also consistent with the field's ongoing interrogations of the binary and hierarchy of center/periphery, for instance through the notion of decentering (e.g., Collective 2021). The purpose of a “new modernist” approach is not the projection of an entrenched, unchanging conception of modern(ist) art making onto a (geographically or otherwise) wider set of practices. Susan Stanford Friedman writes that

a retreat into the comfort zone of a modernist studies based on late nineteenth-early twentieth century “high modernist” experimentation in Europe and the U.S., is neither desirable nor possible. The cat is already out of the bag. And yet, the danger of an expansionist modernism lapsing into meaninglessness or colonizing gestures is real. To navigate between these extremes, I advocate a transformational planetary epistemology rather than a merely expansionist or additive one. (Reference Stanford Friedman2010, 474)

This article looks at Vassos Kanellos as a case study through which to illuminate how Greek dance modernity was performed outside of the Western/European canon. Rather than conceiving of this performance as parallel but separate from Western/Europe, it brings attention to the complex dynamics of center-periphery relationships. Finally, it makes manifest how these dynamics modulated choreographic strategies in “Greek” dance. What follows is correspondingly motivated by these interrogations: How can we acknowledge the input of peripheralized dance artists in early twentieth-century dance modernity, and what can Kanellos contribute toward that history? Beyond projecting Western choreographic concepts and practices or treating peripheralized dance scenes as parallel but disconnected from the West, how can we acknowledge exchanges between “center” and “periphery”? How does Kanellos's biography and artistic production illustrate such exchanges? How were these exchanges negotiated in the uneven playing field of modernity? What choreographic, embodiment, discursive, staging, dramaturgical strategies did Greek dance artists use within this uneven field, and what were their consequences? How was Kanellos placed among them, and how does this relate to his being relatively lesser known even within Greece? How did the specific positionality of Greece—both foundational to Western/European narratives and exoticized by Western/Europe—translate into choreographic practice and the intensive preoccupation of choreography with the nation? What can the example of Kanellos tell us about the ways in which Greek modern dancers articulated internal and foreign pressures in their embodiment and performance of Greekness? Finally, how does his example contribute to acknowledging the diversity of choreographic responses to these pressures?

In what follows, I examine how Kanellos navigated, as a Greek artist, a modern (dance) context in which Greece was not fully admitted. I propose that he used proximity to Western/European forms and expectations, along with underlining difference from them in strategic ways. Moving between the national and the transnational, I articulate how Western/European and Greek performances of Greekness were entangled, turning Kanellos's dance into an embodied negotiation. I look at his dance as a physical act of seeking self-defining agency in an uneven transnational landscape. The first part of this article traces Kanellos's training and artistic career, identifying overlaps and connections that make his work neither a separate part of a “parallel” local history nor reducible to Western/European paradigms: a dynamic interplay of proximity and difference. In this context, I look at the influences of Western modern dance figures (notably Isadora Duncan) and ballet (notably Michel Fokine) and disentangle how these were rendered coherent with his attachment to Greek identity. I read Kanellos's work as a negotiation of two partly opposable and partly complementary conceptions of Greek identity, namely its Hellenic and its Romaic aspects. The following two parts of this article articulate how Kanellos embraced (Hellenic) Western/European visions of the Greek nation while reappropriating them by incorporating Orientalized, non-Western-validated (Romaic) elements. I examine this strategy first on the plane of time, analyzing the conception of history that Kanellos's dance exemplified: insisting on unbroken continuity with Western-validated antiquity while de-westernizing that narrative of continuity through a focus on popular culture as well as Byzantine, Orthodox Christian, and Ottoman references. I then examine his negotiation strategies on the plane of space, identifying the geo-cultural realms that his dance inhabited, between the imaginary of an essentialized nature strewn with antique references and the real-world experience of Greeks facing racialization and discrimination. In the process, I point to the transnational pressures under which peripheralized choreographic nation(al)isms were staged.

Local Inscription, Transnational Circulation: Overlapping Influences in Kanellos's Practice

Kanellos's work must be understood in the multilayered dance contexts in which he circulated. He performed before international dance audiences, primarily in the United States, and explicitly considered his art to be a cultural product exportable for the interest of Western philhellenes (Kanellos Reference Kanellos1966, 64; “To Zevgos Kanellou” 1929, n.p.). His choreography therefore had to ensure international readability, and align with Western/European conceptions of “Greek” dance. Kanellos also extensively performed in Greece and for Greek audiences of the United States diaspora. His choreography therefore also had to negotiate Greek perceptions of Greekness, often to a great extent idealized, especially when combined with the collective nostalgia of diasporic experience. Kanellos had to navigate both the expectations of the culturally dominant West and the internal process of imagining the national community (cf. Anderson [1983] Reference Anderson2006). His embodiment of the nation illuminates the dynamics of choreographically mediating Greek identity in a narrow space between internal narratives and foreign expectations.

At least at first sight, Kanellos occupied this narrow space by underlining the particularity of his dance as Greek. He focused on Greece as a theme and aesthetic model, and presented himself as defined by his being Greek, as a dancer who has “returned to his native sources” and “specialized in his own Hellenic field” (“Eleusinian Festival” 1929, n.p.). He warned against becoming a slave of “foreign innovations” (Reference Kanellos1964, 53) and claimed to “avoid modernisms” (Reference Kanellos1964, 91) in a context in which “modern” was associated with Western Europe (cf. Tziovas Reference Tziovas1989, 21–22). He developed collaborations in Greece, for instance with the Lykeio Ellinidon (Lyceum of Greek Women), a bourgeois-feminist institution promoting physical culture, traditional dance, and spectacular representations of modern Greece's links to its antiquity. He also performed choreography by US-born, Greece-residing Eva Palmer-Sikelianos at the first Delphic Festival, where an idealized ancient past, mediated through tragic theater, was reactivated in the context of modern Greece.

Nevertheless, even a brief overview of Kanellos's biography shows that his dance didn't develop in nation-specific isolation but in contact with multiple Western/European choreographic paradigms and figures. To address these contacts, I methodologically draw from dance and theater scholar Christina Thurner's concept of “the simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous” (Reference Thurner and Franko2017, 526). Thurner develops this idea as a way of countering the impression of linearity present in (modernist) historiography, replacing a view of history as a series of discreet, successive “chapters” by an invitation to make simultaneous coexistence manifest:

The various currents running through and out of twentieth-century theatrical dance certainly evade linear organization and straightforward classification. They all the more comprise a complex network of contemporaneities of the noncontemporaneous that invites comparisons, prefers interpretations to be open, and is conducive to contingency, plurality, and difference. (Reference Thurner and Franko2017, 527)

Thurner's concept invites us to address the confluences, interactions, and codependencies of Western/European and Greek dance histories, as well as the contemporaneity of local and transnational conceptions of “Greek” dance.

Kanellos met Isadora Duncan, a prominent influence in his career, in 1915, while studying at the School of Fine Arts of Athens. Duncan was giving dance classes in her Athenian home, and Kanellos became her student (Fessa-Emmanouil Reference Fessa-Emmanouil2004, 218). Kanellos's own account of his career presented Duncan as its source—their encounter a quasi-mythological revelation. While practicing the pentathlon outdoors in Athens, he recounted, he saw what appeared as a “golden chariot” bathed in sunlight; fascinated, he approached, and replied to Penelope Duncan-Sikelianos'sFootnote 5 “Who are you, boy?” with “Who are you? You must be the ghosts of my forefathers!” (1966, 31). Kanellos's texts contribute to the legend of Isadora, the “supreme woman who gave life even to the stones with her divine art” (Reference Kanellos1966, 21), asserting her intuitive link with Greek antiquity: “Self taught and with her genius and inspiration she discovered rhythms and the secret of the ancient Hellenic dancing” (Reference Kanellos1966, 22). Kanellos remained a carrier of Duncan's physical and kinetic heritage, teaching it to practitioners who are today considered experts of the Duncan tradition (notably Lori Belilove of the Isadora Duncan Dance Company). He retained similarities with Duncan's choreographic approach, drawing inspiration from images on ancient reliefs without exactly reproducing them. Kanellos's artistic relationship with Duncan blended Western/European performances of Greek antiquity with concurrent Greek performances of the same, pointing to looping influences between them. Like other Greek dancers, Kanellos drew inspiration and possibly legitimation from encounters with Duncan. Inversely, Duncan's encounter with and staging of Greek antiquity also constituted a means of aesthetically, artistically, and socially legitimizing her dance.

After studying with Duncan, Kanellos moved to Western Europe and trained at the school of Michel Fokine, who, in such works as Daphnis et Chloé (1912), also displayed a choreographic interest in the imaginary of ancient Greece. Kanellos continued his ballet studies in the United States (Fessa-Emmanouil Reference Fessa-Emmanouil2004, 218). Although his dance bore, from what press reviews and image sources allow us to infer, very limited apparent similarities with classical dance, ballet remained a reference point for him, notably in the exercises included in his training. The aggrandizement of Fokine in Kanellos's writings was similar to that of Duncan: he was presented as a “grand Russian teacher” (Reference Kanellos1966, 66) or even a dancer of “the imperial Russian Ballet Diaghilev [sic]” (63).

A further possible influence on Kanellos's dance were the diverse gestural and rhythmic physical practices proliferating in the early twentieth century. While in the United States, Kanellos met Charlotte Markham, a graduate of the Chicago Art Institute from Manitowoc, Wisconsin. As Tanagra Kanellos, she became his dance and life partner. Vassos claimed to have taught her dance, although he admitted that Markham had a dance background before meeting him, having studied “dance mime” in Paris (Kanellos Reference Kanellosn.d., n.p.). Other sources inform us that she started dancing through an interest in rhythm (“I k. Kanellou” 1930, n.p.). Although most of the material that exists on Kanellos treats Tanagra primarily as his partner, it is reasonable to consider that she transferred aspects of these practices to their common work (cf. Leon Reference Leon2021).

Kanellos's dance also blended with Western musical aesthetics and forms. He often resorted to symphonic orchestration for the musical accompaniment of his pieces, as for example in his collaboration with Isaac van Grove, who arranged ancient hymns for orchestra for him.

Kanellos's practice was therefore conditioned by transnational exchange and influences, integrating multiple layers of Western dance history, from ballet to rhythmic techniques. In terms of Thurner's “simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous” (Reference Thurner and Franko2017, 526), Kanellos's body and practice appear as sites where Western/European genres often historiographically presented as noncontemporary find their simultaneity. From a “new modernist” perspective, Kanellos's artistic path shows the coexistence and intersections of multiple, dominant, and peripheralized modernities. Other figures of Greek modern dance, including the canonical artist Koula Pratsika and Palmer-Sikelianos, also did not work in isolation, but rather in dynamic exchange with Western/European choreographic paradigms.Footnote 6 Greek dance history must therefore be seen not as a parallel, separate set of events widening the Western/European canon, but as a landscape engaging in overlapping, dynamic relationships with that canon.

Kanellos nonetheless presented his dance as essentially Greek, distancing himself from the Western/European modernity he bathed in. This paradox had an elegant solution: the claim that Western/European choreographic paradigms were, actually, Greek. For example, Kanellos criticized Dalcroze while envisaging a “Greek eurhythmics,” through which “the body exercises completely and scientifically with simple and rhythmic exercises” (Reference Kanellos1966, 62, 64–65). He also considered ballet to be “a little remnant, a survival of a much greater, much richer technique of the older dances of Greece” (40). Other artists—Koula Pratsika most notably—claimed to have found an essentially “Greek” dance within Western/European paradigms too (cf. Leon Reference Leon, Kolb and Haitzinger2022).

Kanellos went further in reclaiming “Greek” dance. To explain how this played out, I must introduce a concept crucial in understanding his performance of the nation: “Greekness,” which I am using as an imperfect translation of ellinikotita. Gaining particular relevance in the 1930s, ellinikotita constitutes, as Dimitris Tziovas (Reference Tziovas2008) explains, a bridge between an internally experienced national consciousness and an externally projected national identity. Several other terms also point to this tension. Ethnismos (translated by Tziovas as “nationism”) refers in the Greek context to “a process of exclusion, which determines the differences of the national group from other groups and establishes its ‘otherness’” (quoted in Faubion Reference Faubion1993, 254). The very word(s) describing what is “Greek” also point to an interstitial position. “Greek” (and other Western European variations, such as the Italian Greco-a, the Spanish Griego-a, the French Grec-que, or the German Griechisch) is not used in Greek, except in the form of Graikos, referring to a foreign appellation rather than a self-reference. The Greek language employs the terms Ellines/elliniko, and the contrasting Romii/romaiiko. The former points to “idealized Hellenes of the Classical past” (Herzfeld [1987] Reference Herzfeld1989, 41) and is strongly associated with Western/Europe. The latter refers to Greek identity as it was formed through Byzantine (rather than antique) history, is closely connected to Orthodox Christianity, has a class-marked association with “folk,” and is distanced from Western/Europe, even carrying Orientalist connotations (cf. Herzfeld [1987] Reference Herzfeld1989, 41; Faubion Reference Faubion1993, 57–58). The Hellenic and the Romaic are often viewed as opposed to each other and tend, possibly as a result, to form entrenched, almost stereotyped visions of Greekness.Footnote 7 Rather than reinforcing a binary, I refer to these concepts as concurrent aspects of Greek national identity in the early twentieth century: as performative models influencing the embodiment of Greek identity in its negotiation of proximity and difference from Western/Europe.

It is this negotiation that Kanellos's dance choreographically translated and embodied. Beyond claiming (Hellenic) aspects of his dance relatable to Western/European practices as Greek, he also choreographically represented (Romaic) non-westernized aspects of Greek identity. Modulating proximity with and difference from Western/Europe allowed Kanellos to interweave the Hellenic and the Romaic, accentuating the latter in a choreographic context largely focused on the former. This integration of the Romaic in/and the Hellenic was possibly one of the reasons for Kanellos's historiographic marginalization. It also contributed, in its turn, to excluding those aspects of Greek culture that deviate from the Hellenic/Romaic coupling. The remainder of this article examines how, by fine-tuning Western/European-validated (Hellenic) aspects of Greek identity with non-westernized ones (Romaic), Kanellos reappropriated transnational narratives of Greekness while reinforcing internally dominant ones.

Beyond Antiquity: Reappropriating “Greek” Dance in Time

A major theme in Kanellos's performances was Greek antiquity. This was reflected in his thematic and dramaturgical choices, with works based on myth (The Satyr and the Nymph, Demeter and Persephone), religion (Hymn to Apollo), and tragic theater (The Return of Orestes); other works were more generically presented as “ancient” or “classic” dances (e.g., “Arhei Hori” 1928, n.p.; “I Arhei Hori” 1928, n.p.; Ikonomidi Reference Ikonomidi1928, n.p.). Kanellos's focus on antiquity was reflected in his choreography, loosely associated with ancient iconography, and in his staging, which implicated costuming with “antique” markers: tunics; sandals; warrior costumes complete with javelin, helmet, and shield; and accessories such as flutes. Musical accompaniments were also, at times, based on ancient Greek hymns. Kanellos's focus on theatricality was also inextricably connected with his attachment to antiquity. He danced a modern genre of dance theater as narrative: plot-based works with strongly theatrical choreography. The term “chorodrama,” which he used to describe his practice, is relatable to the amalgamation of dance and theater in ancient Greek tragedy through the tragic chorus’ intermedia, moving-speaking-acting performance. A program for a 1929 performance noted that Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos brought “again to the dance the dramatic, mimetic heart of it which comes from old Hellas” (“Eleusinian Festival” 1929, n.p.; cf. also Kanellos Reference Kanellos1966, 53). Kanellos formalized his approach to choreography by founding the Eteria tou Ellinikou Horodramatos (Hellenic Chorodramatic Society), which aimed to “study and represent ancient Greek dances, to resurrect antique dramas and to represent mimodramas, created on the basis of works of yore, myths, traditions, and popular songs” (Martin Reference Martin1939, 488).

Photo 1. Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos as Triptolemos and Demeter respectively, in a performance based on the myth of Persephone, Elefsis, 1930. Image courtesy of the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA/MIET), The Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos Archive, Folder 1.5.

A focus on antiquity was also present in other Greek artists’ work. Koula Pratsika notably reflected a timeless, almost atemporal ideal of Greekness anchored in antiquity (cf. Leon Reference Leon, Kolb and Haitzinger2022, 64). Her work aligned with the formalized, abstracted conception of Greekness encountered in the prose and poetry of the “Generation of the 1930s” (cf. Tziovas Reference Tziovas1989, 100). Kanellos engaged with antiquity in a way that pluralized Pratsika's (and others’) Hellenism through Romaic elements. He both confirmed the prominent place of antiquity established by Western narratives and claimed the particularity of Greece in relation to the antique past.

The construction of a national history is, as Dipesh Chakrabarty (Reference Chakrabarty1992, 19) reminds us, a modern project, and it is as a modern project staking out a choreographic positionality in the twentieth century that Kanellos's dance placed antiquity on a choreographic pedestal. His work related to the status of Greek antiquity in Western/European consciousness, turning it into necessary symbolic capital for modern Greece (cf. Hamilakis and Yalouri Reference Hamilakis and Yalouri1996). The construction of national identity on the basis of continuity with antiquity characterizes Greek historiography in its imbrications with the elaboration of Greek “fictive ethnicity” (Balibar Reference Balibar, Balibar and Wallerstein1991, 96). This was/is achieved by presenting the modern nation as the proper carrier of the ancient Greek heritage. For Faubion,

by the beginning of the nineteenth century, those Greek nationalists who were courting the favor of the Great Powers were already obliged to inscribe themselves into a developmental matrix that had its instauration in the Athens of the fifth century B.C. and its culmination in Republican Paris. They were obliged, in short, at once to revivify the classical past and to reveal its continuity with an ostensibly “orientalized” present. Their claim of kinship with the European community of nations could stand on nothing less. (Reference Faubion1993, 18)

The argument of continuity was most notably proposed by the highly influential nineteenth-century historian Konstantinos Paparigopoulos, who presented Greek history as a series of phases. Three—antiquity, Byzantium, and the modern Greek kingdom—concerned the historical development of the Greek nation (Paparigopoulos spoke of Greece as a nation even when referring to pre-nation-state eras), and the other two—the Roman and Ottoman empires—concerned moments of its subjugation.Footnote 8 Paparigopoulos's argument, still very present in the construction of Greek consciousness, was partly motivated by a European challenge to Greece's conception of its heritage.Footnote 9 The very project of establishing a continuous history is identifiable in several European countries’ process of constructing a nation-state (cf. Balibar Reference Balibar, Balibar and Wallerstein1991, 86); in its turn, the European nation-state model influenced the development of the Greek nation.

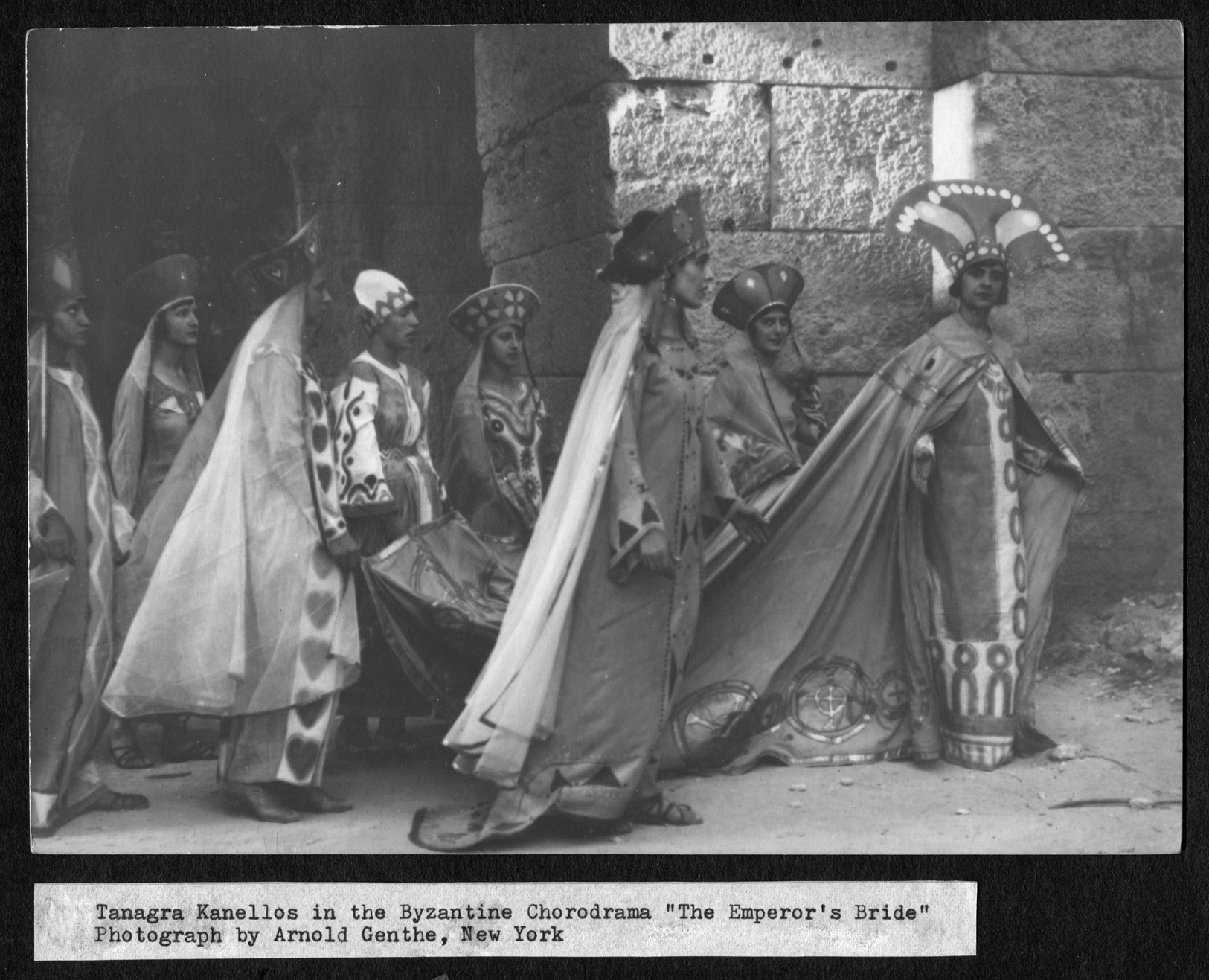

I see Kanellos's work as a choreographic transposition of Paparigopoulos's view of Greek history. Although his performances gave a prominent place to Greek antiquity, they paired this material with dances that referred to Byzantium, the “bridge” between ancient and modern Greece. The chorodrama The Emperor's Bride is the most frequently recurring repertory example of this. In it, Byzantium was present through the thematic focus on Emperor Theophilos (danced by Kanellos) and Kassiane, his ultimately rejected bride (Tanagra Kanellos). Byzantium was present through the choreography, which included scenes recalling Byzantine iconography, like a magnificent procession for Kassiani's entrance followed by a group holding her train. Such actions were underlined through costumes and accessories, drawn according to plates by Tanagra Kanellos. Her designs turned the dancing bodies into moving signs referring to identifiable traits of Byzantine imagery: long, intricately decorated robes; headpieces; a crown bearing a cross for the emperor. The musical accompaniment included Byzantine melodies.Footnote 10

Photo 2. Scene from The Emperor's Bride, staged by Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos, undated. Photo by Arnold Genthe, New York. Image courtesy of the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA/MIET), The Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos Archive, Folder 3.1.

Furthermore, Kanellos choreographically represented the periods during which, according to Paparigopoulos's taxonomy, Greece was under occupation, awaiting its next so-called revival. Characteristic of this was the piece The Martyr, which “symbolized the martyrdom of slavery of the Greek race [genos; see below for more on this term] under the foreign yoke” of, presumably, the Ottomans (“Kalitehniki Parastasis” 1929, n.p.).

Beyond performatively and choreographically rendering the periods composing Paparigopoulos's history, Kanellos presented them as continuous. The program for a 1923 concert in Chicago explained that its three sections corresponded to three periods of “Grecian art”: antiquity (e.g., Hymn to Apollo); Byzantium (The Emperor's Bride, Kassiane); and modern Greece, illustrated through popular songs and dances (“Kanellos Dionysia” 1923, n.p.). According to the program, Kanellos “unites the true spirit of the ancient art with those of Byzantine and the vitality of modern Greece” (“Kanellos Dionysia” 1923, n.p.). This history excluded the traces left by the culturally, ethnically, and religiously diverse Ottoman empire on what became the Greek state.

Kanellos's choreography of a continuous history was a choreographic translation of the Hellenic, Western-idealized dimension of Greekness. In this respect, his work was consistent with the strategies of other Greek dancers of the period who responded to European projections of Greekness, notably Pratsika. The presence of Byzantium and Ottoman elements, however, pushed Kanellos's representation of Greek identity away from the purely Hellenic. Byzantine and Ottoman references were not just steps on a teleological path linking antiquity and modernity. Rather, they ushered in aspects of Greek identity that deviated from Western/European aesthetic paradigms: Orthodox Christianity and peasant, popular, Orientalized culture.

Kanellos's focus on the Byzantine period was paralleled by his interest in “Christian dance” (Reference Kanellos1966, 51), underlining the role of Byzantium in the development of Orthodox Christian identity. By “Christian dance” Kanellos referred to the choreographed aspects of Orthodox Christian rituals like the circling motion of bride and groom during a wedding (51). In ceremonies of Orthodox religion, Kanellos found traces of ancient musical and dramatic traditions (58). Kanellos also had institutional links with the church, which supported his work (cf. Kanellos Reference Kanellos1964, n.p.). The association of his dance with Orthodox Christianity layered the continuity of his choreography of history with a stratum not legitimized by Western/Europe and its Catholic/Protestant underpinnings. It reclaimed “Greek” dance by accentuating Romaic aspects within it. At the same time, the amalgamation of Greek national identity with the Christian religion situated non-Christian Greeks on the margins of Greekness. Kanellos even actively conflated Greece's nondominant ethnic/religious cultures with foreignness. For example, he spoke of “Germanjews (Germanoevraious) … whose soul is foreign towards our natural and national tradition,” (Kanellos Reference Kanellos1964, 56). Such a formulation excluded a minority nevertheless present within Greece from Greekness, opposing its members to an essentialized and naturalized conception of the nation. It more specifically perpetuated the anti-Semitic trope of negating the belonging of Jews in the national community, in this case by conflating them with Germans. Crucially, the quotation was published roughly two decades after the end of World War II, when the exclusion of Jews from European national identities culminated in their systematic murder during the Holocaust perpetrated by Nazi Germany. The genocide of Greek Jews resulted in the loss of sixty thousand people,Footnote 11 as well as the loss of a wealth of cultural heritage that is still only rarely acknowledged as part of Greek culture.

The presentation of traditional dances as bearers of traces of antiquity ensuring its smooth transference to the present was another early twentieth-century choreographic trope representing Greek culture as continuous. One finds this in the work of Palmer-Sikelianos, who used elements of syrtos and balosFootnote 12 in the chorus choreographies of the Delphic Festivals, weaving them into material drawn from ancient iconography (cf. Glytzouris Reference Glytzouris2010, 2097). A similar trend was also present in the work of the Lyceum of Greek Women, which blended revivals of ancient culture with traditional dance performances (cf. Fournaraki Reference Fournaraki and Avdela2010). One also finds such a tendency, albeit in often more abstract ways, in the work of Pratsika, whose group performed both traditional dances and formal variations of them. Therefore, Kanellos presented traditional dances, often as the “modern/present” pole of his tripartite choreographic history. He also used traditional dance elements in modern choreographies, weaving them, like Palmer-Sikelianos, with more archaic-inspired material. In an evening performance for Greece's centennial at the ancient theater of Argos, for instance, dances were conceived based on “myths, representations on ancient pottery and reliefs and on traditional dances and festivals” (“Ta Iraia” 1930, n.p.). The performance of cultural continuity—and therefore singularity—was thus achieved through both a linear sequence of choreographic genres and a blending of past and present in an exemplification of their compatibility. The significance of popular culture, traditional dances in particular, as signs of the cultural continuity of Greece was explicitly articulated by Kanellos:

Our research has been largely in the field of living peoples, and we find important relationships between the dances of the isolated mountain regions and those pictured on the vases and reliefs scattered through the museums of the world, and those dances as described in the ancient writings. We have established the relationship between the pattern rhythms of the dances in the villages and those depicted on the ancient vases and relies [sic], by ourselves making drawings of the dances as they are performed today. The description of the dithyramb by the ancient writers corresponds very remérkably [sic] to the traditional dances—the choirs of men and boys in the circle with their leader soloist. (Reference Kanellos1964, 81)

By presenting traditional dance material as a marker of continuity with the antique past, Kanellos once again underlined the Hellenic aspect of his practice, but his treatment of traditional dance cannot be reduced to that. It also strongly pointed toward a valorization of the Romaic, through links with Ottoman history and the amplification of popular, peasant culture. Indeed, Kanellos's choreographic proximity with traditional dances was complemented by thematic choices referring to popular culture and peasant life in the Ottoman context. One example is To Kleftopoulo (1925). Its title refers to kleftes, armed Greek rebels of the Ottoman period commemorated in the kleftika popular songs and—still today—important figures in the redemptory dominant historiography of the Greek war of independence (in Greece, referred to as the Greek Revolution). This and other works (e.g., Maro's Handkerchief, 1939) were presented in full traditional dress. Kanellos is seen in photographic sources wearing a white shirt, a foustanella, and tsarouhia shoes. The foustanella is a pleated white skirt for male bodies, part of traditional attire in several Balkan countries. It is also strongly associated with official national imagery in Greece, worn notably by the evzones, historically elite military groups whom foreigners today may recognize as the ceremonial guards of the Greek parliament. Tsarouhia shoes, adorned with large black pompons, are also related to both Balkan attire and part of the evzones uniform. This clothing therefore marks Orientalized aspects of Greekness as part of Eastern, post-Ottoman Europe as it has been integrated into an officialized, not fully Western-aligned representation of the Greek nation. Kanellos also used traditional music as an accompaniment to certain parts of his performances. Both visually and acoustically, then, these performances countered the Hellenization of traditional dance by integrating Romaic-connotated aspects. Rather than introducing popular tradition into an abstracted, timeless conception of Greekness characterized by a Hellenic ideal, Kanellos fused this ideal with aspects of still-active popular culture.

Photo 3. Vassos Kanellos as the Kleftopoulo at the Greek Theater of Berkeley, California, in 1925. Image source: Vassos Kanellos, The Antique Greek Dance and Isadora Duncan Illustrated, Athens: n.p., 1966.

Photo 4. Vassos Kanellos in traditional dress, undated photograph. Image source: Vassos Kanellos, The Antique Greek Dance and Isadora Duncan Illustrated, Athens: n.p., 1966.

This proximity with popular culture is also important because the Hellenization of Greek identity was a process largely operated by privileged socioeconomic groups, whose nationalism did not always coincide with popular consciousness (cf. Fatouros Reference Fatouros and Tsaousis1983, 139; Hamilakis and Yalouri Reference Hamilakis and Yalouri1996, 121). Kanellos did at times present peasants in a patronizing way: he wrote that their dances represented “the joyful image and simplistic but also rare rhythm of Greek song and dance” (“Ta Iraia” 1930, n.p.), the term “simplistic” attributing naiveness to their cultural production and implying that an external gaze is needed to recognize its rarity. Such an attitude is compatible with other choreographic work (for instance, by Pratsika or the Lyceum of Greek Women), which, in upper-middle-class contexts of production and dissemination, de/recontextualized traditional dress, music, and dance steps. At the same time, Kanellos's insistence on the Romaic—and the non-Hellenization of the Romaic—deviated from tendencies to appropriate, which often characterize bourgeois choreographic practice. The result can be read as a negotiation between a popular Romaic identity having internalized its cultural relegation and a desire for claiming its aesthetic and artistic qualities.

Kanellos's dance presented antiquity as part of a continuous Greek history: a grounding territory from which modernity sprang. In doing so, his dance conformed to Western/European expectations of a Greek preoccupation with antiquity. At the same time, Kanellos accentuated elements of Greek culture that were Orientalized/Orientalizable: Byzantine heritage, Orthodox Christianity, non-westernized popular traditions, and figures from the Ottoman period. Kanellos thus de-westernized Greek antiquity. This blend placed him slightly apart from his contemporaries in Greece: he embraced the Romios within the Greek and anchored his dance in an embodied experience of layers of history concentrated within modernity, rather than in an abstract, timeless past. This is noteworthy because it accentuated aspects of Greekness that were not part of bourgeois representations of national identity, directed toward Hellenism. It is also noteworthy with regard to an international context in which antique-Greek aesthetics, as reformulated by twentieth-century Western/Europe, were populating choreographic stages to the point of monopolizing imaginaries of Greekness. From a “new modernist” perspective, Kanellos's work troubled the Western-dominated narrative of “Greek” dance in modernity, transforming it from a local perspective.

Beyond Territorial Boundaries: Reappropriating “Greek” Dance across Space

Kanellos's choreographic rendition of the supposed continuity of Greek culture pointed to a linear, even teleological, conception of history. However, his dramaturgical juxtaposition of different periods in common performance programs also collapsed that history into the present that it sought to support. In this flattened history, different moments of the past coexisted within early twentieth-century consciousness and choreographic practice. Modernity can thus be seen as a territory in which different historical temporalities coexisted, in a metaphorical reactivation of Thurner's “simultaneity of the nonsimultaneous” (Reference Thurner and Franko2017, 526). There is indeed a further axis along which Kanellos's dance intervened in Western/European representations of “Greek” dance: space.

Kanellos situated “Greek” dance in a universalist framework, stating that it could express a “great universal truth” (Reference Kanellos1966, 40). He adopted the claim of universal relevance that Western/Europe has historically reserved for itself, and that was transferrable to Greece partly due to Greek antiquity's status in Western/European cultural narratives. At the same time, Kanellos inscribed his work in a national space, supporting his reappropriation of “Greek” dance from those very narratives. His view of Greek dance as universally relevant while bound to an essentialized Greekness can be read against the background of “Great Idea” ideology. In this irredentist view, Greece exceeded its territorial borders, reaching more international relevance, and remained bound to an essentialized ethnic-national identity unifying Greek-identifying communities across space. A crucial proponent of the Great Idea in the early twentieth century was charismatic politician and multiple times prime minister Eleftherios Venizelos, who both morally and materially supported Kanellos's career (according to the artist himself: Kanellos Reference Kanellos1966, n.p.). In these navigations of a simultaneously universalist and essentially Greek space, Kanellos once again oscillated between the Hellenic and the Romaic, making manifest how Western/European perceptions of Greek identity modulated or even violently forced a balance between the two.

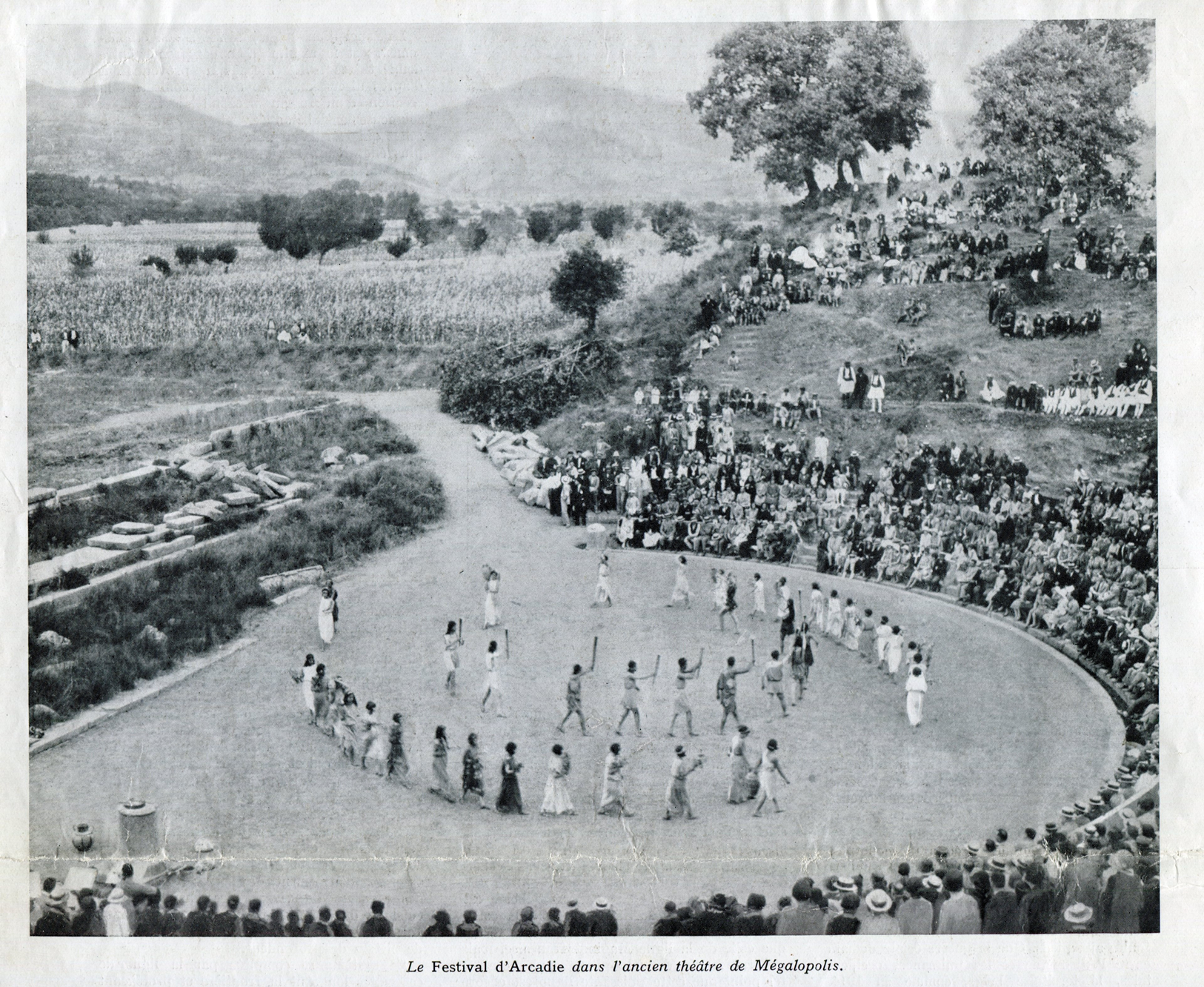

Kanellos often performed outdoors, in ancient theaters throughout the country (e.g., Herod Atticus Odeon, ancient theaters of Megalopolis, of Dionysos in Athens, of Epidaurus, of Argos) and in temples (e.g., of Demetra in Elefsina; of Poseidon on Cape Sounio).Footnote 13 Kanellos also played in closed, modern, urban theaters, especially in the United States (e.g., Carnegie Hall in 1919), and later in his career in Greece (e.g., Kotopouli-Rex theater in 1939). Nevertheless, he expressed disapproval of the proscenium and the two-dimensionality that it created, preferring the three-dimensional plasticity of ancient theatrical architecture (Reference Kanellos1966, 58). Such choices placed his dance in highly symbolic types of space, contributing to the impression that Greece was a more adapted setting for “Greek” dance. There are indications that such an approach was successful: a 1928 press article noted that “the Kanelloses have permission to use any of the theaters at their pleasure. Even the adored Isadora Duncan, whose memory is precious in Athens, never attempted to appear in the ancient theater for performances” (Watson Reference Watson1928, n.p.; the article is referring to a performance at the Acropolis). Venues associable with antiquity provided a sense of legitimacy, notably in the eyes of Western/Europe, of the venues as Greek or better, as Hellenic.

Photo 5. A performance by Kanellos at the ancient theater of Megalopolis, published in L'Illustration, no. 5031, August 5, 1939. Image courtesy of the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive of the National Bank of Greece Cultural Foundation (ELIA/MIET), The Vassos and Tanagra Kanellos Archive, Folder 3.1.

Such venues functioned as manifestations of an essentialized national territory, witnesses to its supposed transhistorical persistence. In this sense, beyond ancient architecture, nature itself played a significant role. Nature was seen by Kanellos as Greek; inversely, Greekness blended with nature. A 1929 program, for instance, spoke of “a freshness of sunlit hills, fragrant with thyme, a joyousness and a truely [sic] Hellenic simplicity” (“Eleusinian Festival” 1929, n.p.). Nature transmitted its (Greek) aesthetics to the choreography: “Out in the open air in the clear light under the open sky, all superficialities of technique have of necessity dropped away, and left only an elemental quality of line and form which is almost sculptural in its presentation” (Kanellos Reference Kanellos1964, 80). Nature functioned as a reference point through history and thus as one more link with antiquity: Kanellos saw, in antique dramatic art, the waves as a model of measure, sea birds as choreographic inspiration, nature in general as a composer (55). Program notes spoke of “Greece … whose every mountain, every river, every stream and every strip of land contains a myth and a story” (“Eleusinian Festival” 1929, n.p.).

Kanellos's focus on an essentialized Greek nature is identifiable in other dances as well as literary works made in Greece at the time. Discussing the generation of the 1930s modernist literary movement, Tziovas (Reference Tziovas1989, 118–120) explains how these authors presented an idealized nature as a way of grounding Greekness in space while abstracting it from folkloric and picturesque connotations. A similar pattern can be found in modern dance. Steriani Tsintziloni, in her study of Koula Pratsika, explains that

the supposedly “Greek spirit,” diffused and immaterial in nature and natural sites became embodied in the dancer's bodies forging them to be conceived into non-bodily but idealist terms. In other words, an abstract idea of Nature, History and Greek nation prescribed the processes of choreographing and perceiving dance establishing a dominant perspective that ignored the materiality of the body on stage, its conditions of labour, and the material conditions of society at large, with long-lasting consequences for dance. (Reference Tsintziloni2015b, 50)

Kanellos played into the Hellenic understanding of a timeless nature that is quintessentially Greek, but also populated this natural space with Romaic bodies. Beyond the nymphs, satyrs, and other chlamys-clad Hellenic figures, his dancing body appeared in traditional attire, reflecting peasant lifestyles of the more recent past. The popular, nonurban, Orientalized body, clothed neither in westernized “modern” fashion nor in West-legitimized “antique” costumes, was allowed to share space with the Hellenic body, acknowledging the multiple dimensions of a nationalized nature.

Kanellos's natural focus is relatable to Western/European dance modernity's general turn toward the outdoors, by artists among whom Duncan, Kanellos's mentor, was prominent. Both in her approach and in the wider physical culture that overlapped with so-called natural dance, contact with nature (barefoot dancing outdoors, motions perceived as natural to the body, loose clothing) was seen as a means of liberating the body from the constraints of urbanized modernity. In Duncan, as well as other “free” or “natural” dance practitioners like François Malkovsky, nature served to ground movement expression as authentic. These natural tropes of Western/European modern dance were strongly influenced by an idealized reception of Greek antiquity: the (ancient) Greek body functioned as a model for accessing “natural” movement (cf. Macintosh Reference Macintosh, Carter and Fensham2011). By connecting nature with the antique-Greek heritage and linking the resulting dance with health and vigor, Kanellos followed early modern “natural” dance's own Hellenic ideations. At the same time, his references to nature differed significantly from Western/European construals. Neither his discourse nor his practice showed evidence of seeing nature as a means toward bodily emancipation; he deviated from the generalized concept of nature fostered by his teacher Isadora Duncan, particularizing nature as Greek, and he saw nature as a mediator of collective belonging and embodiment of a shared, ethnicized space rather than as a model or path toward authentic individual expression. In these ways, he pursued Western/European choreographic tropes while simultaneously de-westernizing them.

Kanellos's focus on nature envisaged a national space independent from political recognition, at a time when Greece was struggling with its status as a geographically “complete” nation. The connection of dance with nature projected an ethnically defined space that corresponded to subjective experiences of Greekness by transcending the geopolitical boundaries fragmenting it geographically. Kanellos's approach to space was thus related to a further concept that purported to unify Greeks in an essentialized category transcending spatial (as well as temporal) boundaries: race. Race was an important notion in early twentieth-century Greek thinking and discourse because of the geographical fragmentation of Greek-identifying populations and because it was bound with nationalist discourse, notably in Metaxas's dictatorship under the idea of a “Third Hellenic Civilization” (cf. Tziovas Reference Tziovas1989, 140). In Greek, “race” can be translated as fyli, a term colored by Western/European, especially Germanic, influences.Footnote 14 But “race” can also be translated as genos, an indigenous term etymologically related to “genetics” and “genealogy.” Genos implies common ancestry and collective familial ties; it refers to a cultural-familial community deemed to have preexisted (and that as such could justify) the foundation of a national, political community.

Kanellos used the term genos, for example, presenting his Martyr as symbolizing the “slavery of the Greek genos” (“Kalitehniki Parastasis” 1929, n.p.). His work was also understood by others through the lens of genos, with one commentator arguing that Kanellos's dance served to “tell to the world that the Greek genia [literally generation, related to genos] is one and indivisible, from its first appearance to today” (quoted in Kanellos Reference Kanellos1964, 30). Indeed, this text specifically referred to Kanellos's work in the United States and should be read in relation to Greek-defining immigrants’ experience of craving connection with the “mother” country, through genos’ familial, community-oriented connotation of Greekness as belonging.

If the use of genos points to an internal self-definition as Greek focusing on communal belonging, Kanellos's also extensively employed fyli (or “race” in texts written directly in English). He interwove the idea of a Greek race with Hellenism: “observing the People dancing today, we look back into the hidden and not forgotten mysteries of the Hellenes who revive; and forward to a race Noble, Vivid, Powerful, Untamed” (“Ta Iraia” 1930, n.p.). This allowed him to reclaim a particular access to “Greek” dance, distinguishing it from other bodies bearing markers of Greekness populating early twentieth-century dance stages.Footnote 15 Kanellos's alignment with a Western, in particular US-American, notion of race is furthermore to be read as a discursive and performative response to racializing attitudes toward Greek people. Although this was not explicitly stated by Kanellos as his aim, I read his use of “race” as an attempt to legitimize modern Greek identity, particularly in the context of immigration to the United States, by integrating it into dominant whiteness. By extension, I read his race-related discourse as a means to legitimize modern Greek cultural production as white culture and preempt its association with artistic forms produced by other racialized groups, even if this implicated reproducing racist tropes about them. Although it is difficult to quantify the extent to which such attempts were successful, they form part of the gradual shift in perception of Greek-origin people in the United States away from the figure of racialized immigrants and as such point to the ways in which processes of integration into whiteness have reinforced the racialization of other groups.

Kanellos's connection of Hellenic identity and race created an overlap between Greekness and whiteness as a socially dominant category in the US-American context. Kanellos toured and performed extensively in the United States, and he had ties with the country by marrying a US-American woman. At the time of his experiences there, the Greek diaspora in the country was not categorized as white—despite being able to, at times, pass. Yiorgos Anagnostu writes that

race, as a core cultural category legitimizing social hierarchies in American society, has prominently factored in the Americanization of the Armenians, the Finns, the Irish, the Jews, the Syrians, and southeastern Europeans, including the Greeks.… Yet, the immigrants also posed an anomaly in the political space of “whiteness.” Although they were legally “white,” their status as racially distinct national groups undermined their full inclusion to normative “whiteness.” (Reference Anagnostu2004, 30, 32)

Greek communities were subject to certain forms of segregation (notably in housing), miscegenation laws (Anagnostu Reference Anagnostu2004, 35), and racist attacks perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan and ranging from physical assaults to everyday microaggressions (Georgakas Reference Georgakas1987, 14, 45). The AHEPA (American Hellenic Educational Progressive Association), under the auspices of and in honor of which Kanellos performed, was formed partly in response to this situation. Its strategy was to promote assimilation in US-American society by asserting Greek whiteness (Anagnostu Reference Anagnostu2004; Georgakas Reference Georgakas2013, 51). In this context, the Romaic aspect of Greek identity, most strikingly perceived as non-Western and “Oriental,” was a liability to be extinguished.

Kanellos translated this negotiation about the status of Greeks as white into choreographic and performative terms. He argued for the (special) place of the Greek-Hellenic “race” within dominant whiteness: “the Greek dance has simplicity, nobility and poise it is the fitting background of the white race” (Reference Kanellos1966, 41). He relatedly introduced “Greek” dance in white-validated models rather than creating alliances with other subaltern artistic agents: for instance, he looked down on “wild” jazz dances, which were, for Greeks, “a degeneration and simultaneously an insult” (53). Although Kanellos does not explicitly refer to African American artists, we here encounter a reproduction of stigmatizing stereotypes regarding Black practitioners of jazz music and dance. The term “wild” activates an image of them as savage, whereas the term “degeneration,” which supposes a teleological conception of cultural progress, reinforces associations of Blackness with backwardness. Kanellos's legitimation of Greekness thus stood at the expense of other US-American racialized groups.

Supporting these positions within Greek discourse meant promoting and reinforcing the self-identification of Greeks as white and therefore as belonging to the Western “community,” thus invisibilizing cultural and ethnic diversity within the country and propping up a conception of Greekness that could underpin discrimination. Such discrimination was present in Greece, notably against Asia Minor refugees arriving after population exchanges with Turkey, who were seen as “Oriental” in opposition with mainland Greeks; their rich popular culture production was absent from Kanellos's Greekness. His blending of Orientalized, Romaic elements into a performance of white Greekness punctured the history of Hellenic-Greek whiteness with instances of deviating from white norms. These punctures nevertheless remained within the history of Greek whiteness: the Romios was allowed to manifest only under the condition of remaining coherent with the Hellene—not with the post-Ottoman, the Balkan, or the Mediterranean—to the expense of recognizing cultural heterogeneity escaping these two figurations of Greekness. Kanellos placed a transnationally homogeneous (white-Hellenic) Greekness above an intranational, heterogeneous, not always white one, as well as above transversal alliances and solidarity with other racialized communities.

Kanellos's treatment of nature and race was consistent with Western/European dominant narratives. The construal of nature as an aesthetic model proposed notably by Duncan, the relegation of non-white dance, the ideal of a territorially unified nation-state and of privileged whiteness, all reproduced Western/European values within and beyond choreography. Kanellos's dance particularized these narratives by rendering them specific to Greek early twentieth-century experience. His focus on nature localized Duncan's nature into a sense of place that transcended Hellenic ideals by being lived in by (Romaic) Greeks. Albeit sporadic, his references to genos sidelined racializing definitions and spoke to Greek-identifying people residing outside of national space. From the perspective of “new” modernism, his dance shifted from Western/European projections of space by situating itself in the Greek periphery. At the same time, his navigations among the nuances of Greek race(s) reproduced both externally influenced and internally defined exclusions from Greekness, creating a fallacious homogeneity covering the diversity that existed in Greek national space and reinforcing exclusions from the national community. By strategically navigating the requirements of whiteness, Kanellos propagated racist stereotypes against other groups in the United States, reminding us that peripheralized cultures’ negotiations with dominant narratives may reinforce discriminations against other oppressed groups, and that the relative privileges that Greece holds, due to its (however precarious) belonging to the Western imaginary, can and has become a basis for further exclusions.

Conclusions

In the framework of new modernist studies, this reading of Vassos Kanellos's oeuvre proposes that a widening of (dance) modernity cannot be reduced to a search for Western/European-defined choreographic practices and concepts within peripheralized modernities. Kanellos's dance incorporated elements of Western/European dance modernity, filtered through the influence of his ballet teachers, Duncan and Tanagra Kanellos, but transformed, recontextualized, and blended with material from local tradition and Orientalized aesthetic models. The example of Kanellos illustrates that dance modernity is to be construed as a weblike formation of bidirectional—at times partial, at times conflicting—exchanges and influences, dominant and marginalized practices forming parts of a network of “contemporaneities of the noncontemporaneous” (Thurner Reference Thurner and Franko2017, 527). Correspondingly, Greek dance modernity needs to be acknowledged not only in its very existence, but also in its exchanges with Western/Europe.

Identifying links between Kanellos's practice and Western/European ones can lead to legitimizing his work because of its relatability with the canon, once again reiterating the West as a guarantor of relevance. However, the introduction of dominant paradigms into new contexts adapts and reworks them, as happened with Kanellos's weaving Duncan's aesthetic and ballet influences with traditional dance or Byzantine references. These circulations and transfers upset dominant dance-historical narratives (e.g., the separation of ballet and modern dance) and point to the periphery as a space where dance histories can be rewritten. At the same time, Kanellos's often disparaging comments on discriminated groups remind us that the troubling of hegemonic narratives by peripheralized figures has often been done at the expense of other oppressed (dance) cultures, rather than in a movement of transversal solidarity.

The circulations and exchanges that make up an expanded history of dance modernity happened in an unequal landscape. Greece's position in the uneven landscape of early modern dance was modulated by its concurrent status as foundational to the story Western/Europe tells of itself and as a nation not fully adequate to modernity. The choice of several Greek modern dance artists, Kanellos included, to focus intensely on the nation, can be attributed to their exclusion from Western/European modern dance's supposed universalism. In this sense, nation-centered or even nationalist dance needs to be understood through transnational historiography. The example of Kanellos points toward strategies of reappropriation of national narratives, reclaiming them through context-specific shifts in the interstitial space between foreign projections and local/internal experiences, contaminating those narratives with elements (in Kanellos's case Byzantium, Orthodox Christianity, and Ottoman popular heritage) that are not consistent with Western/Europe's narrative of itself. That Kanellos remains a largely unknown figure even within Greece nonetheless points to the limits of real-world influence his response to Western/European narratives can be assumed to have had.

Many of Kanellos's strategies are comparable with other figures of Greek (dance) modernismFootnote 16 but also display dissimilarities with other modern(ist) artists, including within choreography—notably Koula Pratsika—who focused primarily on Hellenic attributes. Kanellos's de-westernizing tendencies illustrate the diversity of strategies early twentieth-century artists adopted regarding internal and foreign pressures on the embodiment of Greekness. These differential responses had, and still have, consequences. The choice to deviate from Western/European expectations about the performance of Greekness increases the incompatibility of choreographic work with a canon of modern dance making that privileges a Western-validated Hellenism. This canon still influences the focus of both practical and historical education in dance in Greece, whereby only parts of the country's dance heritage are systematically transmitted to contemporary artists. The choice to embrace a Romaic-informed Greekness can—and in Kanellos's case did—promote an essentialized, religiously and ethnically homogeneous concept of the nation, reinforcing the peripheralization of minorities. Although Kanellos's choices reappropriated the performance of Greekness from a Western/European choreographic grip, his work excluded non-ethnic Greek and non-Christian Greek citizens from national identity. These groups are even more starkly absent from (dance) history, their perspective silenced by precisely the types of discourse that Kanellos produced. Kanellos's performance of the Romaic was the reminder of the perspective of the peripheralized on their own identity; simultaneously, it was an internally dominant narrative that operated its own exclusions. The dominant/dominated binary is thus replaced by a process of seeking interwoven and multiscale dominations.