1. Introduction

Stop thief! Stop thief! Murderers! Assassins! Justice, merciful heaven! I'm done for, done to death. They've cut my throat! They've stolen my money!

In Molière's play The Miser, the Parisian bourgeois Harpagon so despairs at the theft of his money that he loses the will to live. ‘Aah! my poor, dear money, my lovely money, my friend, they've taken you from me! And now you've gone, I've lost my prop, my comfort, my joy. I'm finished. There's nothing for me now. I can't live without you. It's the end, I can't go on, I'm as good as dead and buried.’ The play contrasts Harpagon's love affair with his money, kept in his precious chest – ‘Oh my lovely money-box!’ – with the true romances that develop between his son Cléante and Mariane, and between his daughter Élise and Valère. Hope for justice appears when Harpagon meets an officer of the recently established police lieutenancy in Paris, but the officer quickly discerns that it is impossible for him to apprehend the culprit. When the officer asks ‘Who do you suspect of committing this theft?’, Harpagon replies ‘everybody. I want you to arrest the whole city and the suburbs too.’ For Harpagon, prosecuting theft was so uncertain that the only way to guarantee justice was to incarcerate all of Paris. Yet ultimately there was no theft, as Harpagon's servant, master Jacques, had conspired with Cléante to conceal the money so as to bargain with Harpagon and secure Cléante's marriage with Mariane. In the end, both couples are happily married, Harpagon is reunited with his chest, and the officer is left demanding his fee. Harpagon points his finger at master Jacques: ‘See him? I give him to you. You can hang him – that should settle the bill!’Footnote 1

Molière's comedy continues to entertain audiences because it performs a widely shared condemnation of avarice, taking direct inspiration from Classical Greek and Baroque Italian theatre.Footnote 2 Parisians in the audience during Louis XIV's reign also observed how the play mocked bourgeois pretentions, at a time when financiers made gargantuan profits that enriched their families and left taxpayers carrying an unsustainable burden of state debt. For many Parisians, especially the magistrates in the parlement who risked losing their place in the social hierarchy to the rising class of financiers, moneylenders were the men whose theft from the state coffers caused most concern.Footnote 3 Yet around the time that The Miser was first performed in 1668, Parisian elites and royal ministers largely turned a blind eye to these financial matters as they enacted reforms that aimed to maintain order in the capital, including a crackdown on petty theft. They established the hôpital général in 1656 to incarcerate vagrants, and the police lieutenancy in 1667 to keep peace in the streets.Footnote 4 In 1670, a council of leading magistrates convened by the king's minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert finalised a new criminal ordinance that sought to reform abuses and enforce the rigour of the law, although in practice it mostly clarified and updated points set out in the 1539 ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts.Footnote 5 Concerns about the problem of theft in the reign of Louis XIV gave Molière the opportunity to generate such ridicule and mirth, as his troupe's performance made a critical intervention in contemporary social debates.

This article examines the extent to which French subjects took theft seriously in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and asks whether the idea that thieves might be apprehended and punished was anything more than a joke and a bourgeois fantasy, as Molière's characterisation of Harpagon might suggest. French historians have set out contrasting interpretations of theft under the Old Regime, but they have not always reached their judgements on the basis of substantial evidence from the surviving criminal archives of this period. Pierre Chaunu sparked an enduring debate when he argued in 1962 that officials administering criminal justice in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France were preoccupied with acts of serious violence, and only began to engage substantially with property crime in the eighteenth century, as emerging capitalist modes of production encouraged rampant profit-seeking behaviour, including for some an illicit pursuit of money by any means possible.Footnote 6 Early modern historians who grew frustrated with the limits of Chaunu's manner of argument, which generalised statistical trends from unrepresentative local sources, turned instead to legal anthropology as they emphasised alternative, informal means of conflict resolution that took place outside the formal proceedings of criminal justice and defied quantification; in this view, disputes over theft seemed unlikely to come to court in the first place.Footnote 7 Most historians of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century criminal justice seem to implicitly accept Chaunu's chronology, as they tend to study spectacular crimes such as homicide and witchcraft, which played the most prominent role in the public image of the courts in this period and have continued to do so since.Footnote 8

The history of theft under the Old Regime in France is not an entirely neglected topic, but existing research into this subject is fragmentary, and no substantial interpretation has emerged to replace Chaunu's ‘violence to theft’ thesis. Historians of the later Middle Ages have shown how thieves sometimes received a pardon thanks to the royal arbitration of justice, depending on the severity of their crime.Footnote 9 By contrast, historians of the eighteenth century have traced the social and institutional developments which made legal sanction for theft a greater threat than ever before.Footnote 10 Yet the period in between remains largely unexplored, neglected in part because of the uneven survival of archival sources, and the organisational and paleographical challenges these records pose.Footnote 11 At most, some significant work has identified the place of theft prosecutions during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in local studies throughout France and its borderlands, but these have not been subject to comparative analysis or evaluated as part of wider trends.Footnote 12 As a result of this state of the field, the history of crime and criminal justice under the Old Regime has undergone a transformation since Chaunu published his pathbreaking argument, yet he remains a central point of reference, and a fundamental aspect of his initial claim remains unchallenged: the idea that the French subjects and magistrates neglected to prosecute theft with any degree of success before the eighteenth century.Footnote 13

This is a significant oversight, because it leaves the impression that informal modes of conflict resolution prevailed in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France, whereas the evidence presented in this article demonstrates that property disputes involving theft were difficult to settle informally, and that victims of theft took recourse to the courts more often than historians have allowed. To make that argument, this article builds on recent research into crime and criminal justice across early modern Europe, which demonstrates that theft was often numerically the most significant category of crime prosecuted by judges and magistrates in courts with the power to execute criminal justice in defence of public order, as opposed to those who adjudicated disputes between parties, which belonged instead to the field of civil justice.Footnote 14 Although theft is an apparently near-universal category of crime that forms part of legal codes throughout world history, it is also one that changes over time in ways that depend on economic and social relations, property regimes, and legal cultures.Footnote 15 In early modern Europe – especially in the eighteenth century, when surviving records become more abundant and accessible – theft was also the form of serious criminality that most prominently involved women, whether as agents in the illicit economy or as victims of men's attempts to criminalise them.Footnote 16 Sex-workers were frequently associated with theft, not least because men wagered they might be able to reclaim money or goods they had lavished on their mistress by alleging their property had been stolen, but also because of the role of brothels as sites of illicit sociability.Footnote 17 Often thieves apprehended and brought before the courts were outsiders who operated on the margins of communal life, and took a risk that anonymity might afford them greater opportunity to evade detection or escape infamy if caught.Footnote 18 Theft was more likely to be prosecuted in cities, where a proliferation of jurisdictions and officials gave urban residents more immediate access to justice, and made arrest an ever-present threat.Footnote 19 The incidence of theft sometimes grew at moments of economic crisis which brought dire poverty,Footnote 20 but it also evolved with the new opportunities afforded by demand for novel goods and the consequent spread of luxury shops and second-hand trading.Footnote 21 Organised bands of thieves and smugglers capitalised on these developments and forged new commercial associations to trade beyond the pale of the law.Footnote 22 In these ways, recent research has demonstrated that chronological, geographical, and gendered variations in the sites, objects, victims, and agents of theft were more significant than any straightforward shift under the Old Regime ‘from violence to theft’.

Building on recent studies into property crime in early modern Europe, this article argues that French subjects did take theft seriously in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, even if at times that meant subjecting it to ridicule. In the conceptual terms of modern criminology, it takes a ‘Left Realist’ approach to interpret theft not as the simple product of unequal property relations, poor life choices, or unilateral cultural labelling, but rather as a complex category of crime that engages perpetrators and victims in dynamic social relations, and is constructed through both informal and formal constraints, for example via mediation, public debate, and the practice of criminal justice.Footnote 23 State provision of justice could hardly guarantee punishment for offenders, and so Part 2 of this article assesses the many factors that prevented accusations from coming to court. Yet similar sentiments to those expressed by Harpagon emerged in pleas submitted to criminal courts throughout the kingdom, particularly in the archives of the appellate courts of the parlements of Paris and Toulouse, whose jurisdictions covered more than half of the French population. The records of these parlements furnish the main evidence for this article through an extensive process of record sampling, evaluated in Part 3 and discussed in more detail subsequently.Footnote 24 These archives are significant because they conserve the most substantial surviving records of the practice of criminal justice in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France, whereas the records of most local jurisdictions and courts of the first instance have not been conserved. This analysis of the records of the parlements of Paris and Toulouse suggests that attempts to prosecute theft in this period did not only – or even primarily – emanate from state officials, but instead arrived in court instigated by plaintiffs who sought to defend their property and make a principled statement that they would not stand for its loss. When theft disputes did come before the courts, judges and magistrates assessed them at length, within a complex hierarchy of appeals, in which the plaintiff and magistrates were responsible for managing the cost of proceedings, and not the accused themselves.Footnote 25 Officials who acted on complaints of theft worked hard to pursue them with the full force of the law, despite the major systemic constraints in the practice of criminal justice at the time: the jurisprudence of magistrates in the parlements concerning theft is the subject of Parts 4 and 5. Audiences for The Miser perhaps hoped to identify with the young couples whose love conquered all in the finale, yet the findings presented in this article suggest that many French subjects nevertheless shared much in common with Harpagon as they cried ‘au voleur!’ (‘stop thief!’) and prosecuted theft more often than they cared to admit.

2. The limits on prosecuting theft

Harpagon's despair at his inability to find justice would have made sense to theatre audiences who were used to the many limits on prosecuting theft under the Old Regime. It is important to assess these limits in order to evaluate how plaintiffs and magistrates overcame them when they did pursue their complaints with success. One major limit on prosecuting theft related to jurisprudence; theft was difficult to prosecute because it could not always be identified with precision. Evolving debates about property and law posed a major challenge to jurists who tried to define theft as a category of crime in the early modern period. Paolo Prodi has argued that in the early Enlightenment, jurists began to classify theft as an entirely secular crime, and detach it from religious notions of sin.Footnote 26 Intellectual historians have similarly emphasised that this was an age of European imperial expansion, conquest, and expropriation, in which the problem of theft raised moral and theological issues for authors who debated how claims to property were justified – for example by ownership, possession, power, or use – and how they might be protected and enforced.Footnote 27 Jurists working in Roman and Canon law traditions, who held in balance these legal doctrines with the royal and customary laws that equally applied in France, weighed up all of these issues and more when evaluating theft. The relevant article of Justinian's Digest (47.2.3) at the outset defined theft in simple terms as ‘the fraudulent handling of anything with the intention of profiting by it; which applies either to the article itself or to its use or possession, when this is prohibited by natural law’.Footnote 28 Yet additional articles in this chapter of the Digest (47.2) presented myriad possibilities that attempted to delimit the potential scenarios any magistrate might encounter.Footnote 29 Dozens of royal pronouncements under the Old Regime led to an accretion of decrees that specified new examples of what was called ‘qualified theft’, or theft in circumstances which required an aggravated punishment.Footnote 30 For example, a royal ordinance of 1677 – reissued in 1682 and 1706 – proclaimed that theft committed at the royal court would be punished by death, although this order did little to help officials at Versailles locate those responsible for reported thefts around this time.Footnote 31 In the early eighteenth century, famous thieves became the object of admiration among civic elites who applauded plays about their exploits, and devoured pamphlets that reported their latest attacks on luxury, yet their celebrity was an exception to the norm that theft was regarded as illegitimate claim to property.Footnote 32 The problem lay in clarifying that norm and applying it through the practice of the courts.

Crime writers reflected a more fundamental concern under the Old Regime that opportunistic thieves pursued their illicit business with impunity. François de Calvi in his best-selling History of Thieves (first published in 1623) lamented:

it is too apparent, that the one half of the world robs the other; the greater theeves robbing the lesse: for this is so miserable an age, that the great ones rejoice at the tottering of the lesse; and many are seene standing under the gallowes to be as spectatours of the execution of others, who have more often deserved death then they have committed thefts.Footnote 33

Calvi's claims had great reach among readers, but they are difficult to assess because he concealed his sources, embellished his tales, and gave his subjects pseudonyms to conceal any direct link with contemporary cases.Footnote 34 Calvi drew some of the stories featured in his history from notorious cases reported in recent pamphlets, which gave his account a realistic credibility.Footnote 35 Others he claimed to have gathered at the foot of the scaffold or from documents shown to him by court scribes.Footnote 36 Yet the apparent realism of his most elaborate tales might be treated with scepticism, including what he called the ‘choake-pear’ [‘poire d'angoisse’], ‘a kinde of instrument, in the likenesse of a little bowle; which by the helpe of small springs within it, might open and inlarge it selfe; so that being clapt into a mans mouth it could not be removed without the key purposely made to that end’.Footnote 37 When Calvi drew lessons from these sometimes fantastical histories, he exhorted his readers to take theft seriously as a sin and a crime, and if ever they risked succumbing to temptation then they might take steps to ensure they might ‘be led from the precipice of perdition, into the safe way of vertue and honestie’.Footnote 38

Like Calvi's subjects, many thieves escaped formal sanction under the Old Regime, and so their activities typically produced little evidence in archival records. Yet sometimes lingering allegations of theft left traces in investigations for different crimes. These traces reveal how the victims of theft did not neglect their assailants’ actions, but were instead prevented from pursuing them before justice through the mechanism of the criminal law of theft. The blind violinist Henri Millot – who said that ‘he lost the view in one eye when struck with an arrow, and in the other from a blow with a knife’ – was accused of witchcraft by his mother-in-law, but he alleged instead that she sought to prevent him from prosecuting her for theft after she seized his goods when his wife died. He claimed that ‘they pillaged and stole all of his possessions, but the judges of Bar-le-Duc refused to accept his denunciation of the crime’.Footnote 39 Such claims need to be treated with caution, since they often arose at moments when those accused of crimes sought to discredit the witnesses against them. Hugues de Montbéliard denounced Philippe de Lorgelot, who accused him of homicide, as ‘the bastard son of a whore and a gentleman’, and ‘a knave and a thief, who wickedly stole the majority of his grain and furniture, and that by God if he found him tomorrow in the fields he would kill him with a musket shot’.Footnote 40 The vehemence of these courtroom confrontations makes it difficult to distinguish between plausible allegations and common insults based on status and worth; Jeanne Harnois denied allegations of witchcraft levelled against her by Loisel Lois by responding simply that ‘he's a wicked man, which means he is a thief’.Footnote 41

Despite the common lament that thieves went unpunished, theft disputes might still have been resolved through informal mediation. Some victims who did apprehend their assailants agreed to proceed no further so long as the thief returned the stolen goods.Footnote 42 If children or servants committed theft within the household, male authorities might have taken it upon themselves to impose an appropriate punishment, and not proceed to make a formal complaint. An early sixteenth-century exterior door panel from northern France depicts a steward beating with a rod a servant who failed to conceal purloined pewter dishes in his bodice; this panel likely served as a warning to all servants passing through that their steward would impose similar punishment should they fall prey to temptation and pilfer any household goods.Footnote 43 Sometimes victims of theft did make a formal plea before a criminal court, but then did not pursue their cause any further, most often because the thief could not be identified.Footnote 44 Such unresolved pleas nevertheless demonstrate how plaintiffs came to present themselves before the courts to register their version of events and have them transcribed in an authorised record that could later be cited as a point of reference, whether to pursue the culprits or exculpate the plaintiffs.Footnote 45

Other victims who sought a more formal agreement sometimes found settling before a notary less costly and time-consuming than pursuing full court proceedings, but first they had to compel their opposing party to agree to their terms.Footnote 46 In 1606, the labourer Pierre Laurent brought his lodger Jean Viennot before the Parisian notary Hugues Babinet to settle a dispute with another lodger named Nicolas Charpentier. One morning Charpentier had set off down the road to Meaux wearing Viennot's hoses, which had 66 livres in the pockets. Viennot sent three men to catch up with him, which they did at Neuilly. After a quarrel Charpentier eventually returned the hoses to Viennot along with the reduced sum of 38 livres. Charpentier tried to pass off the theft as an honest mistake, and the landlord Laurent sought to avoid a dispute under his roof. The notary's mediation settled the dispute such that Charpentier repaid Viennot the sum he owed plus additional recompense, and Viennot declared that he accepted the payment as an end to the quarrel, ‘without further recourse’.Footnote 47

However, it seems that theft was less commonly settled outside of court compared with violent disputes of a more public character. Local priests also mediated conflicts among their parishioners, and saw reconciliation as a major part of their mission, but priests tended to act more frequently as mediators in family matters, debts, and conflicts among neighbours, and were less likely to intervene in property disputes when thieves often came from outside the community and were difficult to track down.Footnote 48 Manuals for confessors offered guidance for reconciling thieves with their consciences, but not owners with their goods.Footnote 49

Magical practitioners suggested alternative means to identify thieves and locate stolen property. Their claims perhaps distracted potential plaintiffs away from the law courts and towards more speculative means of resolving their disputes. Magistrates saw these magical practitioners as illegitimate competition whose activities should be curtailed. One line of questioning pursued by the Paris magistrates in their interrogation of Eustache Texier, accused of witchcraft, was to ask ‘who taught him to divine thefts, and to say that the parish priest of Orsay stole the seigneur's furniture’.Footnote 50 Although this form of divination was often associated with witchcraft throughout Europe, authorities in late seventeenth-century Lyon apparently gave it greater legitimacy when they had employed Jacques Aymar, a peasant from Saint-Veran in Dauphiné, to locate thieves on the run. Aymar's supporters sought to explain his successes by natural causes, including ‘the vestiges and impressions in the air caused by murderers and thieves’.Footnote 51 Others were suspicious of Aymar and his spectacular results with the divining rod; they alleged his supporters espoused bad science, devilish magic, or a ridiculous fraud.Footnote 52 Their criticisms suggest that it was possible to believe so much in the importance of theft detection that it risked merely provoking ridicule. In this sense, the informal alternatives to prosecuting theft were diverse and promised significant rewards, but they were far from foolproof.

3. Evidence from the parlements of Paris and Toulouse

Despite these limits on prosecuting theft, there is vast surviving evidence of victims’ recourse to criminal courts to resolve their disputes over stolen property. The scale of the surviving records is overwhelming, notwithstanding many archival losses before the eighteenth century, especially the archives of courts of the first instance. At the heart of this article is an analysis of a sample of theft cases tried in the two oldest and most prestigious courts in the kingdom, the parlements of Paris and Toulouse, courts with appellate jurisdictions together that covered over half of the French population, comprising much of north-central France and all of Languedoc respectively. This article considers these courts together because their archives have complementary strengths and weaknesses, and are much better conserved than the records of the other major parlements which sat at Aix-en-Provence, Bordeaux, Dijon, Grenoble, Rennes, and Rouen.Footnote 53 The criminal archives of the parlement of Paris are conserved largely in complete series from the mid-sixteenth century until 1790. The registers of incarcerations (registres d’écrou) of the conciergerie, the gaol attached to the parlement which held appellants to the criminal chamber, among all manner of other detainees, are sufficiently detailed and consistent to permit serial, quantitative analysis of the pattern of appeals and verdicts (see Figure 1). The registers of interrogations (registres des plumitifs) conducted in the criminal chamber before the magistrates reached their final verdict also permit qualitative analysis, although these interrogations are often brief and summary, since they were conducted on the basis of case files that have not been conserved, and which were most likely sent back to subordinate courts on the conclusion of a trial.Footnote 54 By contrast, the criminal archives of the parlement of Toulouse contain over 100,000 case bags (sacs à procès), of which around 13,000 have been catalogued to date, including 831 cases of theft up to 1700 (see Figure 2).Footnote 55 These case bags are exceptionally rich sources for qualitative analysis. They are far richer than the records conserved from the criminal archives of the parlement of Paris, since in each case they contain various interrogations, sentences, and miscellaneous records of proceedings from subordinate courts – which typically do not survive in Paris or elsewhere – although they rarely contain the final verdict on appeal in Toulouse.Footnote 56 It is nevertheless difficult to submit the Toulouse records to meaningful quantitative analysis because the number of case bags available is determined by a highly selective process of cataloguing, which leaves around 90 per cent of the case bags unclassified, despite a major ongoing project in the Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne.Footnote 57

Figure 1. An entry in the registres d’écrou of the conciergerie, showing five men accused of theft from a coffer. Source: Archives de la Préfecture de Police de Paris (hereafter APP) AB 56, fo. 81r, 1670-03-25. Note: This sample entry, concerning a case discussed below, shows the information recorded in the registers of incarceration in the conciergerie, including the name and (often but not always) declared status of the appellants, the sentence in the court of the first instance, the category of crime, and the verdict on appeal in the parlement. This case initially proceeded before the court at Sainte-Geneviève-du-Mont in Paris, on the instigation of the directors of the hôpital général. The accused were sentenced either to galley service or banishment, as well as whipping and branding, and a fine of six livres. The magistrates largely confirmed the sentence but in one instance reduced the fine and abolished the other punishments.

Figure 2. Trials for theft from the seventeenth century conserved among the criminal archives of the parlement of Toulouse, showing 831 catalogued cases in August 2023. Source: https://archives.haute-garonne.fr/archive/recherche/sacsproces/n:109 [accessed 2 August 2023].

Cases tried on appeal by the magistrates in the parlements represent only the most serious crimes liable to some form of corporal punishment. Yet these cases matter not only because they have been conserved from this period, but also because they set the norms of procedure and jurisprudence for judges in subordinate courts to follow. Justice under the Old Regime was arbitrary. This means that judges and magistrates reached their decisions with discretion on the basis of the evidence before them, the principles of Roman and Canon law, and the provisions of royal and customary law; they did not apply a systematic approach to sentencing, much to the frustration of their Enlightenment critics.Footnote 58 When deliberating in matters of theft, magistrates in the parlements examined closely the particular circumstances of the crime and the quality of the evidence presented. It could be a matter of life or death for the accused whether a theft took place in daytime or at night, in the street or in a church, with violence or after a break-in, but all of these points were difficult to discern if the evidence was incomplete or contradictory.Footnote 59 Magistrates also made sure to examine the accused themselves and – if necessary, and when feasible – order further witness interrogations or expert opinions on material evidence, such as broken locks or the instruments used in break-ins.Footnote 60 In coming to their decisions on verdicts, the magistrates often drew fine distinctions between categories of punishment, and made marginal amendments to the duration of sentences to galley service or banishment, or to the sums demanded in fines.

These fine distinctions appear particularly clearly in the jurisprudence of magistrates serving in the highest court in the kingdom, the parlement of Paris. The evidence presented here draws on sample years selected from the earliest period of the surviving records in the mid-sixteenth century until the end of the seventeenth century, when changes in recording practices add further layers of complexity.Footnote 61 Additionally, to assess the impact of political instability, significant years during the Wars of Religion (1562–1598) and the civil wars known as the Fronde (1648–1653) have been included, as well as the year 1685 which saw the greatest number of appeals to the parlement before the later eighteenth century. The years 1589–1594 have been grouped together because appeals dropped to such low levels during this phase of the religious wars that some years would otherwise not be visible on the chart.Footnote 62 The year 1642 and not 1640 has been selected because the scribes responsible for the registers in 1640 did not record the categories of crimes.Footnote 63 Within this series of documents, theft cases represent between one-quarter and one-third of all appeals, which makes property crime a major part of the magistrates’ judicial business, with an equivalent share of appeals to crimes of violence.Footnote 64

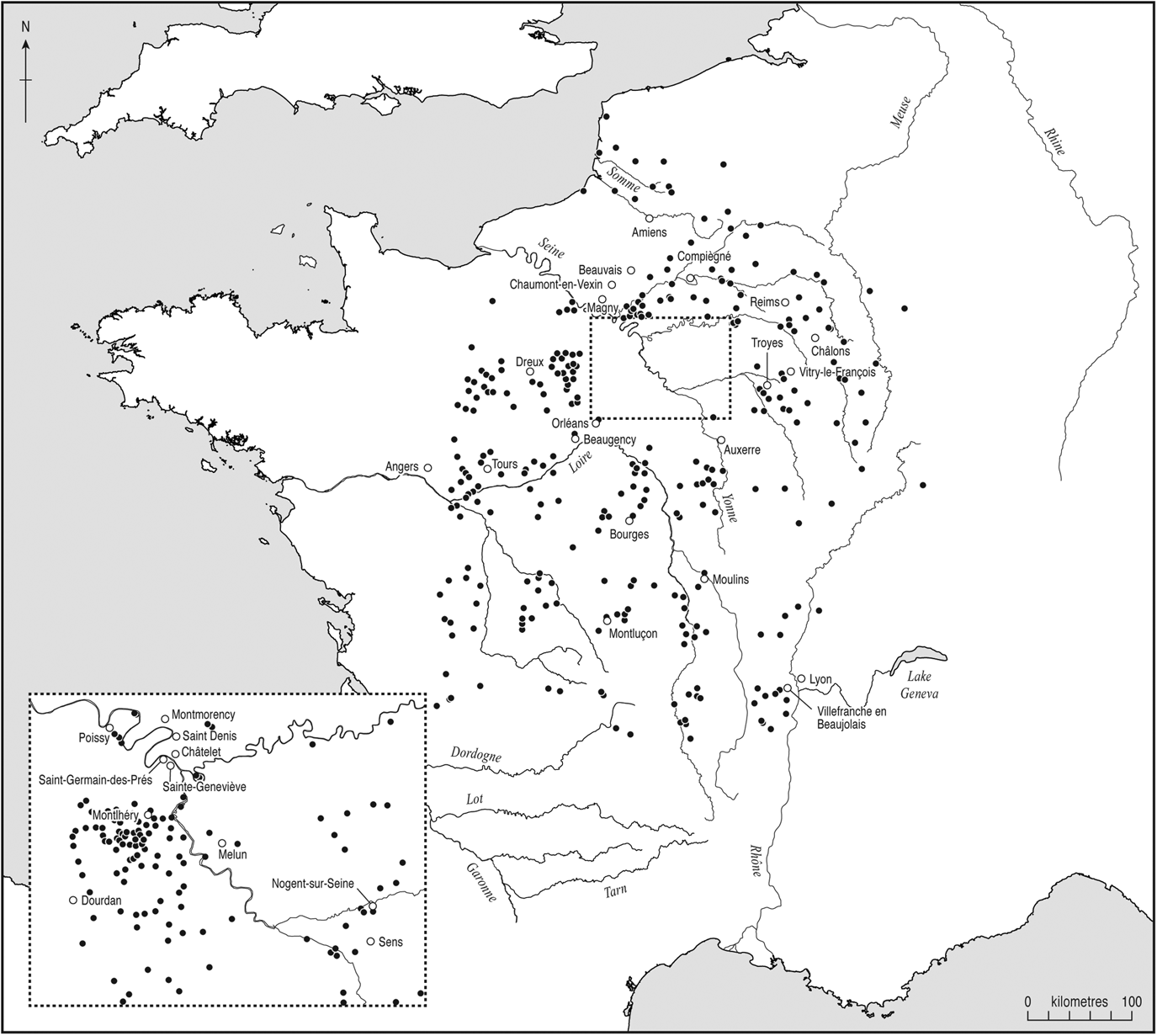

Appellants to the parlement of Paris arrived to the conciergerie from across the court's jurisdiction in the sample period (Figure 3). Appellants in the sample of theft cases especially came from the principal criminal court with jurisdiction in the first instance in the capital, the Châtelet (647 out of a total 2,338 cases), and to a lesser extent from other Parisian courts such as Sainte-Geneviève (45) and Saint-Germain-des-Prés (35), as well as major cities in the court's core jurisdiction such as Lyon (33), Angers (25), Orléans (25), Troyes (25), and Tours (23), and notably not from its largely rural outer reaches.Footnote 65 This pattern might suggest that serious theft was predominantly committed and prosecuted in cities, as historians have found elsewhere in early modern Europe.Footnote 66 Yet the appeals that came before the parlements bear little relation to the incidence of crime in society, as they had already been filtered by judges in subordinate courts who determined which cases might proceed in the first instance and then move up to Paris on appeal.Footnote 67 Even the thirty-three theft cases that came from Lyon on appeal to Paris in the twenty-one sample years under consideration surely represent only the tip of the iceberg of cases tried in local and regional courts such as the sénéchausée.Footnote 68 Nevertheless the fact that even this many appellants from Lyon travelled the near 300 miles to Paris, funded by the plaintiffs and judges in the court of the first instance, demonstrates that the wheels of justice under the Old Regime were capable of moving along serious affairs when the conditions permitted.

Figure 3. The origins of appeals to the parlement of Paris in 2,338 theft cases, in sample years between 1572 and 1690.

Note: Named outline dots show courts that sent more than ten appellants to the parlement in theft cases during the sample years.

Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10–11, 14, 19–20, 29–30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71–2. Map composed by Chris Orton and Michele Allan of the Durham University Cartography Unit.

Recent research into the history of criminal justice throughout early modern Europe has shown that most disputes went to trial not primarily because of the intervention of state officials but rather at the instigation of plaintiffs.Footnote 69 Many plaintiffs benefitted from significant wealth and connections when they pursued a denunciation, and so in this sense they might be said to have used the courts to enforce a degree of social control over their neighbours and subordinates.Footnote 70 This interpretation applies at least in some cases tried in France under the Old Regime. For example, when Samuel de Castelpers, vicomte de Cadars, suspected his former servant Louise Ester Valette had stolen his bedsheets and food to sell via a dealer in stolen goods married to the notary in the village of Bornac, he detained her in the dungeons of his château for five days and instigated a prosecution before the sénéchaussée in Rodez.Footnote 71 Cadars was an influential nobleman whose family participated in the Estates General of Languedoc. He could readily afford to issue a monitoire (monitory, or summons) to be read out in the parish church, and pay the expenses for the dozens of villagers who travelled from Bornac to Rodez.Footnote 72 Key witnesses provided the evidence judges required to counter Valette's claims that she simply took spare sheets to make clothes for her son, and that any beans she carried away, or grain she baked in the seigneurial oven, were a gift for the notary's son during his illness, all authorised by the vicomte. Villagers insisted that Valette had been seen carrying away substantial quantities of food, and had cut up the vicomte's best sheets without permission. Judges in Rodez accepted the witness testimony and sentenced Valette to be banished, even though they acknowledged the risk that the witnesses were subjects of the vicomte, who often served in his household, and so were biased towards the prosecuting party.

Yet not all plaintiffs were nobles exerting control over their subjects; others made the most of the resources available to them for personal gain. In November 1685, the young soldier Antoine Lerou denounced the lantern-carrier Gérard Picard and the pauper Arnaud Doizan before the judges of Sainte-Colombe-en-Bruilhois, a town outside of Agen.Footnote 73 Lerou claimed he was returning home from Bergerac, where he had served as a dragon (dragoon) billeted in a Huguenot household to force them to convert.Footnote 74 Lerou accused Picard and Doizan of stealing from him the 500 écus he had seized from Protestant families. The pair had followed Lerou from Agen and assaulted him on the road, then led him to a tavern at Sainte-Colombe where he alerted the local judge and town councillors, who rapidly apprehended the pair. Perhaps Picard and Doizan considered that Lerou claimed his spoils illegitimately, despite the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes that year which justified his booty, since it ordered Protestants to flee the kingdom or face confiscation of their property and worse. The judges at Sainte-Colombe upheld Lerou's claim and confirmed his account of events with witnesses at the tavern. They sentenced Doizan and Picard to serve in the galleys in perpetuity, and restored to Lerou his bags of coins. The proceeds of Lerou's dubious pillage both made him a target for thieves on the road from Agen and gave him the means to pursue his complaint at Sainte-Colombe. Defence of ill-gotten property, not social control, motivated this young dragoon as he pursued his complaint before justice, and he found local justices willing to intervene on his behalf.

The manner in which cases came to court varied considerably according to circumstances, and the surviving sources do not permit a comprehensive analysis of the pattern of arrests or the identity of plaintiffs. In general, records from the criminal archives of the parlements of Paris and Toulouse give the impression that plaintiffs were not all wealthy elites, although registering a plea before a court typically demanded a degree of social standing, as well as access to money and resources, to gather sufficient witnesses and cover court costs, including the fees involved in sustaining an eventual appeal.Footnote 75 Among the decade sample years consulted, the largest surviving number of case files catalogued in the criminal archives of the parlement of Toulouse dates from 1660 (thirty-eight cases catalogued as involving theft). The plaintiffs in these cases include one priest, four noblemen, three widows (two of them noble), six office-holders, four citizens of towns (bourgeois or habitants), three syndics acting on behalf of civic or religious organisations, a tanner, two farm owners, and the chapter of an abbey. At least three cases proceeded ex officio, on the instigation of the public prosecutor without the financial support of a partie civile (civil party, who sponsored the prosecution).Footnote 76 The surviving criminal archives of the parlement of Paris do not permit a direct comparison of the plaintiffs involved in instigating each case. The registers of incarcerations from 1660 identify the plaintiff in only fourteen out of fifty-nine cases involving eighty-seven appellants, since royal prosecutors often took responsibility for financing a case after the initial sentence was appealed, and so the plaintiff in the court of the first instance is not prominently recorded. Nevertheless, it is suggestive that among the plaintiffs whose status is recorded are an office-holder in a sovereign court, a tax official, a miller, a butcher, a merchant, and the syndics of the hôpital général.Footnote 77 These plaintiffs, among others whose ranks are more difficult to discern, took theft seriously enough that they were willing to denounce incidents before criminal justice and pursue cases on appeal when they might otherwise have settled outside of court. Although judges and magistrates could and did on occasion initiate investigations in their official capacity, they never did so systematically or as the result of any avowed or implicit movement to assert state control. As far as it is possible to tell, it was typically on the instigation of plaintiffs that investigations took place, and their actions demonstrated that victims of theft might well make use of the formal instruments of justice across the jurisdictions of the parlements – and not only informal mediation – when pursuing their disputes.

4. Punishing theft

When cases of serious theft did come before local judges, and those judges issued a sentence of corporal punishment or a substantial fine, then major royal ordinances issued in 1539 and 1670 stipulated that the case should proceed on appeal to a superior court, such as the parlement of Paris or Toulouse. The relatively consistent and systematic records kept by the magistrates in Paris enable a quantitative analysis of their jurisprudence, which reveals how they evaluated the cases that came before them with discretion and attention to detail. The Parisian magistrates’ decisions to apply different categories of punishment in theft cases tended not to vary considerably over the long run. The magistrates typically revised down what they considered to be excessively punitive sentences issued by judges in subordinate courts, often by transmuting death sentences into galley service, and galley service into banishment, or otherwise varying the duration of these punishments (Figure 4).Footnote 78 Their decision making was clearly informed by the gender of appellants, in part because women tended to be less frequently accused in incidents of violent theft, but also because magistrates almost always refused to condemn women to service in the galleys (Figure 5).Footnote 79 Beyond these common categories of punishments, applied in the most serious thefts that came before the parlement of Paris on appeal, the magistrates also applied a litany of less severe punishments such as whipping, branding, shaming rituals, and fines, including combinations of several of these penalties (listed as ‘other’ in Figures 4 and 5). Many accused thieves were simply released or received the verdict plus amplement informé (‘until further information is forthcoming’), according to which they were freed to all intents and purposes, but nevertheless required to present themselves before the court if required.

Figure 4. Punishments in sentences issued by judges in subordinate courts, compared with verdicts judged by magistrates in the parlement of Paris (x-axis), in 2,338 theft cases tried on appeal, in sample years between 1572 and 1690, counting by individual appellants (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

Figure 5. Punishments in sentences issued by judges in subordinate courts, compared with verdicts judged by magistrates in the parlement of Paris (x-axis), in 484 theft cases tried on appeal involving women, in sample years between 1572 and 1690, counting by individual appellants (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

The number of appeals to the parlement of Paris in theft cases remained fairly stable over the long run, and fluctuated primarily along with the total number of appeals in all cases. This means that appeals declined substantially during the final phase of the religious wars and again in the Fronde.Footnote 80 A major gaol-break in the Paris conciergerie on 10 May 1652 permitted thirty-four accused thieves to escape before the magistrates issued a verdict in their cases; eight of them had been sentenced to death by the judges in the first instance.Footnote 81 Appeals reached a peak in 1685, after royal ministers’ botched attempt at financial reform left the Châtelet with a large budget surplus, and deprived courts elsewhere in the kingdom of necessary funds to conduct their business (Figures 6 and 7, compared in Figure 8).Footnote 82 Historians characterise this period as one of a decline in recourse to judicial violence, but the magistrates in the parlement of Paris remained consistently reluctant to condemn to death an accused thief from the very first surviving records in this series in the mid-sixteenth century, apart from in rare circumstances where they considered the evidence supported a conviction for qualified theft in serious aggravating circumstances.Footnote 83 The magistrates ordered the death penalty in a greater number of cases in moments of political turmoil during the religious wars and the Fronde, when violent thefts involving soldiers make up a prominent portion of appeals.Footnote 84 Recourse to torture declined dramatically over the period, however, as the number of sentences involving torture coming to the parlement in theft cases fell from 23 in 1572 and 26 in 1589–1594 (around one-sixth of appeals in theft cases) to between 3 and 10 per year throughout the seventeenth century, and almost none by the century's end (Figure 9). Of the total of 122 appeals involving torture across the entire period, the magistrates issued the death penalty in three cases.Footnote 85 They made greater use of punishments of galley service and banishment than the death penalty throughout this period, and especially towards the end of the seventeenth century (Figure 9). Ultimately, as the magistrates revised the sentences that came to them on appeal from subordinate courts, and decreed their typically more moderate verdicts, they asserted the role of the parlement of Paris as a supreme court of appeal, since they alone claimed the right to define the appropriate penalty for serious crimes across their jurisdiction.

Figure 6. Sentences issued by judges in subordinate courts and brought on appeal to the parlement of Paris, in 2,338 theft cases tried in sample years between 1572 and 1690 (x-axis), counting by individual appellants (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

Figure 7. Verdicts judged by magistrates in the parlement of Paris in 2,338 theft cases tried on appeal, in sample years between 1572 and 1690 (x-axis), counting by individual appellants (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

Figure 8. Initial sentences (S) compared with verdicts (V) judged by magistrates in the parlement of Paris (x-axis) in 2,338 theft cases tried in sample years between 1572 and 1690 (x-axis), shown in percentages (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

Figure 9. Torture ordered in sentences issued by judges in subordinate courts and sent on appeal to the parlement of Paris in 2,338 theft cases, in sample years between 1572 and 1690 (x-axis), counting by individual appellants (y-axis). Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30, 36, 39–42, 48, 56, 65, 68–9, 71, 72.

5. Social status, property, and violence

Pierre Chaunu's ‘violence to theft’ thesis generated a major debate in the social history of crime and criminal justice in the final third of the twentieth century, as some historians pushed his claims further, arguing that theft prosecutions intensified in the eighteenth century as a result of the class conflict produced by the emergence of industrial capitalism.Footnote 86 Recent research has not found such clear-cut results, and instead suggested that plaintiffs and accused thieves alike often shared a common social milieu, or were separated rather by minor distinctions of class and status.Footnote 87 The relationship between social status and punishment in theft cases is most clearly measurable in the sample of appeals to the parlement of Paris, because when appellants arrived in the gaol of the conciergerie to testify before the magistrates reached their verdicts, they also declared their status to the scribe in the gaol, and their responses were systematically recorded in the first half of the sample period at least. Figure 10 categorises the declared status of the appellants in theft cases in a camembert chart, taking a narrower range of sample years than previous figures because the scribe in the conciergerie did not record declared social status in most theft cases in the sample years after 1630.Footnote 88 This chart reinforces the findings of historians working in other parts of early modern Europe, as it shows that the appellants who came before the parlement of Paris accused of theft presented a broadly representative sample of the fine-graded distinctions that characterised the social hierarchy of the Old Regime, especially in the capital, as its courts of the first instance sent the largest proportion of appeals to the parlement of Paris.Footnote 89 The same historians who argued for an association between the status of accused thieves and the emergence of industrial capitalism claimed that the labouring classes were more likely to be condemned to death for theft in the early modern period, because of elites’ desire to reinforce their claim to power through their domination of property relations. But the sample of appeals to the parlement of Paris demonstrates that this was not necessarily the case, and instead that the status of accused thieves punished by death broadly reflects the overall pattern of appeals (Figure 11), although many of those condemned to death did not have their status recorded in the registers of incarcerations and might have been paupers, so it is impossible to draw a firm conclusion on this point. Magistrates came to their decisions over theft cases based on discretion, in which status was but one variable among many others relating to the circumstances of the crime.

Figure 10. Appellants to the parlement of Paris in 1,080 theft cases, in sample years between 1572 and 1630, showing declared social status, counting by individual appellants. Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30.

Figure 11. Accused thieves condemned to death in the parlement of Paris in 155 cases, in sample years between 1572 and 1630, showing declared social status, counting by individual appellants. Source: APP AB 4, 6, 10, 11, 14, 19, 20, 29, 30.

Although theft could be an essential survival strategy for the poor, the very poorest in Old Regime society make up only a small portion of appellants to the parlement of Paris in theft cases.Footnote 90 Perhaps many of the poorest women and men accused of theft were detained or cast out as vagrants, and simply not brought to trial at all, or else were turned away by the court of the first instance; necessity due to dire poverty could provide a legitimate excuse for theft in the Canon law tradition at least.Footnote 91 After Jean Delande pleaded that ‘he stole out of necessity, and has four young children as well as debts of 35 livres’, the magistrates in Paris overturned his sentence of banishment issued in Romorantin, and released him with an injunction to improve his behaviour in the future (enjoindre de bien vivre).Footnote 92 Claude Perron, tried on appeal from the Paris Châtelet, received the same outcome after he explained that ‘he is a wain-wright and he was arrested because he took some herbs from the fields in order to sell them so that he could have bread’.Footnote 93 However, most others who made the same defence were not so fortunate.Footnote 94 And not all accused thieves pleaded necessity in the criminal chamber with sufficient tact. Léonard Martin had his sentence of whipping and banishment from Saint-Denis confirmed on appeal after he denied that he climbed over a wall to steal apples and cabbages, but when pressed he admitted that ‘it is true he took lettuce to make a salad’.Footnote 95 Some vagrants accused of theft came before the parlements on appeal – they declared that they lived all over (‘partout’) and had no social status (‘de nul estat’) – but their numbers remained small.Footnote 96 Rather than plead poverty and necessity, appellants more often insisted that they had not in fact committed theft because they were owed money or missing wages.Footnote 97 Unpaid wages, or wages granted in kind, posed a particular problem for domestic servants and apprentices who depended on the benevolence of their masters. Yet if they sought to retrieve their pay by illicit means they also faced a severe penalty, as domestic theft counted as a qualified theft liable to be punished by death.Footnote 98

Just as those accused of theft often claimed their opposing parties owed them something, so did plaintiffs assert claims to have their property returned.Footnote 99 Stolen goods piled up in the greffe (scribes’ office) during the course of an investigation, although the surviving records do not systematically note the objects of most thefts. Nevertheless, in the sample years of appeals to the parlement of Paris, the records of fifty-six sentences and thirty-six verdicts in the registers of incarceration include an order for the restitution of stolen goods, mostly sums of money or jewellery, but also some bulky items such as cauldrons, coffers, and a curtain from a church at Dreux.Footnote 100 Sometimes the stolen goods were brought to the parlement along with the appellants. When a sergeant from Bar-sur-Aube brought four appellants to Paris accused of theft during the night, he carried with him the object of theft, a ‘musket with its mechanism, its barrel measuring three-and-a-half feet long and sawn at its end’.Footnote 101 During the Cartouche affair in the early 1720s, the procureur du roi (crown prosecutor) Guillaume François Joly de Fleury maintained lists of stolen goods which might be returned to their owner should someone present a legitimate claim, such was the volume of loot seized during this unprecedented crackdown on organised theft.Footnote 102 Some items could also be used for evidence in the trial, but this was rare and interrogations focused on witness evidence instead.Footnote 103 In the case of Antoine and Jacques Chevet, the stolen goods were not kept to be returned. This father and son pair appealed to the parlement from Dorat against a sentence of death on the wheel for killing two masons with an axe they had stolen, and the sergeant who led them to Paris brought along the axe head and leather purses which they had seized after the assault. These objects feature briefly in the final interrogation, which suggest the magistrates considered them among the body of evidence, but the case files of the initial investigation in Dorat do not survive to determine this point.Footnote 104

Other items were simply left over in the scribes’ office out of neglect. Figure 12 shows a key and a small leather pouch left over in the scribes’ office in Toulouse after the trial for theft instigated at Sainte-Colombe by the young dragoon Lerou against Doizan and Picard (discussed above) in which the key and pouch barely feature. Doizan said that this was ‘was the key to his father's house’, but the judges suspected it might have been a skeleton key. Apparently the need to return the key and pouch never arose as Doizan and Picard were condemned to galley service, and Lerou was content to retrieve the money he had lost, minus any court fees demanded.Footnote 105 The circulation of items related to theft investigations shows that the cases which came to the parlements on appeal were driven by plaintiffs’ demands for restitution as well as magistrates’ requirements concerning the correct proceedings for an investigation. Yet equally these lingering objects reveal that plaintiffs sought more than just the restitution of their goods, as otherwise they might have settled out of court and saved the hassle of a full investigation and appeal. Plaintiffs, like judges and magistrates, also wanted to see justice done in cases of theft that embroiled victims and accused thieves in complex social and economic ties, mediated by property as a category of possession and also, sometimes, of proof.

Figure 12. A rusty key and its leather pouch, from a case bag conserved as ADHG 2B 2736. Source: Archives départementales de la Haute-Garonne 2 B 2736.

In his classic text that helped to mark out the social history of crime as a field of research in postwar France, Chaunu suggested that officials in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries did not take theft seriously because they were preoccupied with the problem of violence rather than the defence of property in itself.Footnote 106 Many theft cases tried in this period did involve violence to different degrees, but so did cases tried in the eighteenth century.Footnote 107 Cases of theft associated with homicide and assault tried on appeal by the magistrates in Paris were far more likely to involve the death penalty in the initial sentence and the final verdict, and in rare cases these punishments consisted of breaking on the wheel.Footnote 108 These cases more often occurred during and after periods of civil war, especially the religious wars of the later sixteenth century and the Fronde in the mid-seventeenth century.Footnote 109 Theft aggravated by violence was also a particular problem in cases when thieves worked in organised groups to extort property with force and weapons.Footnote 110 But organised gangs used their nicknames to signal their ingenuity as well as their menace: a group accused of robbing the coffers in the parish church of Saint-Barthélemy in Paris declared that among their number were men known as la Liberté (‘liberty’) and la Pensée (‘thought’ or ‘idea’; also a flower, the pansy). Perhaps Quentin Demetreville gained the latter nickname for quick thinking, as he insisted to the magistrates that they only went inside the church ‘during the rain, to hear mass’. But although this excuse perhaps helped Demetreville to escape with only a reduced fine, it did not save the rest of the group from a verdict of galley service or banishment, in addition to whipping, branding, and a fine.Footnote 111 Considering the overall pattern of appeals in theft cases to the parlements of Paris and Toulouse, violence and theft existed in tension throughout the period of the Old Regime, as perpetrators considered the means necessary to achieve their ends, and magistrates came to their decisions accordingly.

6. Conclusion

When French subjects discussed theft in common parlance, they exchanged reassurances that the crime would be punished one way or another. Several such commonplaces were collected and translated by the lexicographer Randle Cotgrave for his 1611 French–English dictionary: ‘the theefe will be at length discovered’, or ‘such theefe, such halter; a punishment befitting th'offence’.Footnote 112 The qualitative and quantitative analysis presented in this article shows that these commonplaces were not just idle talk. They conveyed a meaningful sense that French subjects took theft seriously as a crime that might plausibly be prosecuted through criminal justice, and if it was not prosecuted then alternative solutions would emerge, even if that meant waiting for God to provide. This view is radically different from the paradigmatic interpretation set out by Pierre Chaunu in 1962, when he argued that the main trend in criminal justice between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in France was a shift ‘from violence to theft’, so that only in the later period did theft become a preoccupation for officials in criminal courts in a new age of capitalist commerce.Footnote 113 But it is a mark of how little historians have taken premodern theft seriously since then that no historian has put forward a feasible interpretation on the basis of substantial evidence from surviving criminal archives above a highly localised level.Footnote 114 The contrast is stark between the relative lack of research and debate concerning the history of theft, and the abundance of research and controversy concerning crimes of violence and witchcraft, which are major fields in their own right. Major interpretations of premodern theft tend not to reflect the practice of justice according to the evidence presented in this article and elsewhere. Michel Foucault's notion of mass institutional incarceration as a means to repress the poor in a movement of ‘great confinement’ under the absolute monarchy has limited relevance for theft cases primarily instigated by plaintiffs, although the directors of the hôpital général in Paris did on occasion initiate investigations. His interpretation reveals perhaps more about his attitude to state authority in mid-twentieth-century France than it does about social relations in seventeenth-century Paris.Footnote 115 Paolo Prodi suggested that notions of theft became secularised in the transition to modernity, such that theft increasingly became treated purely as a juridical category of crime and no longer as a sin, but if this shift did occur in legal and literary discourses then it took place later than the period analysed here, and not before 1700.Footnote 116 Readers of François de Calvi's best-selling History of thieves continued to revel in his association of sin and crime throughout the seventeenth century, while sacrilege remained a form of aggravated theft that magistrates might punish severely.

Instead, the abiding impression from the analysis of the evidence presented here is one of general continuity and localised fluctuations in judicial and extrajudicial responses to theft between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in France, in common with trends elsewhere in Europe.Footnote 117 Statistical analysis of the criminal records from the Old Regime can only reveal patterns in the internal business of the courts, rather than external trends in behaviours, and so Chaunu's premise was to this extent misjudged. Yet the practice of the courts is an important subject in its own right, as criminal justice sources reveal the extent to which plaintiffs had recourse to the law to resolve their disputes in the first instance, as well as the manner in which magistrates considered their cases on appeal. The surviving criminal records of Paris and Toulouse reveal that from the earliest surviving records of interrogations in the mid-sixteenth century, plaintiffs, judges, and magistrates continued to bring prosecutions for theft in substantial (if not spectacular) numbers throughout the Old Regime, with some variations particularly in moments of civil strife or financial experimentation. A significant result of this analysis is to demonstrate both quantitatively and qualitatively the resourcefulness and flexibility of criminal justice in France already in the mid-sixteenth century, which stands out in Europe for its complex judicial hierarchy and centralisation, despite the criticisms of Enlightenment jurists who condemned its arbitrary and punitive tendencies.Footnote 118 Theft is perhaps a better marker of the relevance of justice to plaintiffs than a more public and prominent crime such as homicide, since theft disputes were so easily left to lapse. Yet theft was still often prosecuted throughout the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and perhaps earlier too, although the surviving records are not sufficient to give a firm indication of developments in patterns of prosecution since the later Middle Ages.Footnote 119

Despite these criticisms of Chaunu's outdated view of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, he was right to suggest that prosecutions for theft changed in character during the eighteenth century, although they did so not necessarily in ways he anticipated. Recent research has revealed some significant developments in approaches to prosecuting theft in the eighteenth century, when the underlying structures of appellate justice persisted from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but were subject to reform or rivalry with emergent institutions of law enforcement. Although the overall number of appeals to the parlements remained fairly stable in the eighteenth century, as in the previous 150 years, they increased notably in the 1780s as officials implemented financial and procedural reforms that required appeals from seigneurial courts in all serious cases, when previously these jurisdictions had been less likely to send cases on appeal before royal courts.Footnote 120 Another major change took place in cities, where the institution of the police lieutenancy became established throughout the kingdom, and grew especially in Paris, where from the mid-eighteenth century the Sûreté office served as a first port of call for denunciations and investigations into all manner of crimes, especially property crimes.Footnote 121 Police commissioners and their inspectors, installed in every quarter of the capital, offered additional recourse to justice, and in some quarters they specialised in retrieving stolen goods or actively sought out pickpockets on the streets.Footnote 122 Magistrates in the parlement of Paris developed a new kind of judicial response to theft in the early 1720s, when they collaborated with officials in the police lieutenancy and the maréchausée (the marshalcy, with jurisdiction over the highways and soldiers) to pursue the Cartouche gang. They launched an unprecedently large investigation, which for the first time deployed massive state resources into pursuing an organisation they suspected comprised more than eight-hundred members.Footnote 123 Smugglers also grew their trade in the eighteenth century to take advantage of increasingly integrated global markets and poorly supervised customs arrangements.Footnote 124 At some moments, and in certain jurisdictions, theft cases came to be tried after 1700 in greater numbers than before, and this was largely as a result of expanded and better financed institutions of criminal justice, whose officials built on the solid foundations laid over the previous 150 years or more.

This article has demonstrated that theft posed a consistent problem for state and society during the Old Regime, a problem so serious that it also inspired Molière's great comedy The Miser, and ensured its longevity on stage. The play's leading comic character Harpagon expressed a common sentiment when he announced that ‘there is no punishment great enough for the enormity of the crime; and if it remains unpunished, the most sacred things are no longer secure.’Footnote 125 Opportunistic and sometimes impoverished thieves continued to pilfer and pillage throughout the period and beyond, while victims and plaintiffs, judges and magistrates sought appropriate judicial or extrajudicial responses. These formal and informal constraints shaped the actions of French subjects who might not have themselves been the victims of theft, but who engaged in common gossip and sometimes spectacular cultural representations of thieves. It is only by analysing theft as a complex category of crime, constructed in the conflicts between victims and perpetrators, via formal and informal constraints, that the significance of Molière's play makes sense as an exemplary product of the legal culture of Old Regime France. Harpagon may have cried wolf when he called out ‘stop thief!’ in performances of The Miser, but audiences knew that theft posed a real risk in their society; they followed Harpagon's example, albeit with greater discretion, and prosecuted theft before criminal courts when circumstances permitted it.