1. Introduction

The practice of polyandry in which several – generally closely related – men share a wife is extremely rare, although it was somewhat more common in the past. Globally, it was most prevalent in South Asia, particularly in Tibet.Footnote 1 Polyandry appears to have been a reaction to specific ecological, demographic or economic constraints. In Tibet, it occurred where fertility of the land was limited, where outmigration was very difficult and where further subdivision of land was not feasible; the plots were becoming too small to sustain families for all brothers. Furthermore, it has been described as a ‘sensible marital strategy’ to cope with the heavy tax burdens and corvée labour imposed on Tibetan families.Footnote 2 Polyandry existed in Sri Lanka as well. The most extensive historical descriptions relate to the interior region, the former Kingdom of Kandy, that was independent until 1815. In his history of late Kandyan society, Ralph Pieris notes that polyandry was widespread, especially in the form of two brothers sharing a wife.Footnote 3 Poverty was often mentioned as the reason for this arrangement. For instance, two brothers Dingirāla and Mendumarāla declared in 1823 to the Judicial Board of Commissioners for the Kandyan Provinces that ‘since they inherited so little land from their father, they were obliged to be content with one wife between them’.Footnote 4 The practice was, however, also found among wealthy families. Therefore, it appears that its main purpose was to avoid further fragmentation of land. This was always a real threat in Sri Lanka as land was divided equally among all children, although sons were expected to remain on and exploit the family estate. According to Pieris, Kandyan polyandry was probably also stimulated by high sex ratios, themselves possibly caused by female infanticide. Finally, he mentions the traditional system of compulsory labour services (rājakāriya) that could take men away from home for long periods of time. It was a good solution to have a brother at home to take care of the farm, the joint-wife and the children.Footnote 5

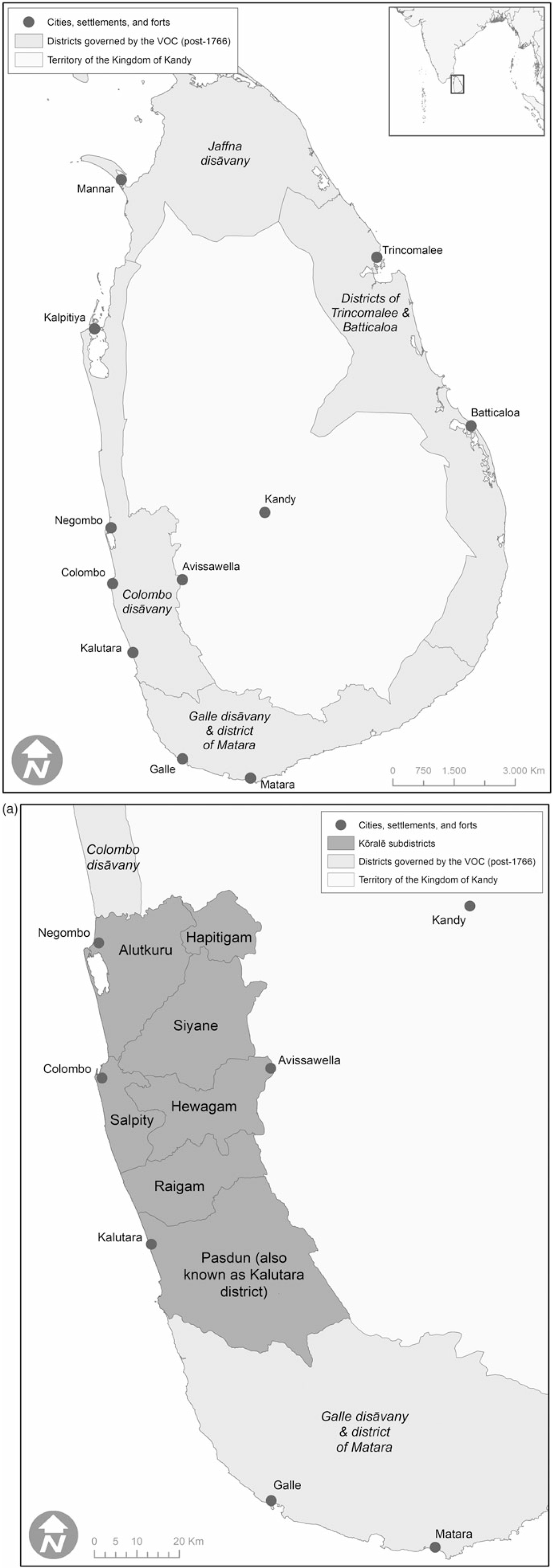

Outside of Kandy, colonial rule had been present since the sixteenth century, predominantly in the coastal areas (see Figure 1 and 1a). Nineteenth-century British commentators claimed that polyandry had disappeared there due to this Portuguese and Dutch colonial, Christian rule. For instance, Sir James Emerson Tennent, a former colonial secretary of Ceylon, wrote: ‘The…custom was at one time universal throughout the island, but the influence of the Portuguese and Dutch sufficed to discountenance and extinguish it in the maritime provinces’.Footnote 6 The eminent social anthropologist Stanley Jeyaraya Tambiah followed this when he stated ‘polyandry in the maritime provinces had virtually disappeared under the attacks of intolerant colonial powers which viewed the practice as savage and ridiculous and contrary to Christian ethics’.Footnote 7 Indeed, the Dutch official statements on the matter had been unequivocal. In a 1773 plakkaat (ordinance) against ‘crimes of all sorts’ it was stipulated that:

whoever is found to have had incestuous intercourse with his next of kin shall lose his property, and will incur physical punishment or even be put to death. The next of kin being not only blood relatives but also those who have come through marriage into the family. Thus the shameful intercourse of a brother with his brother's wife shall be punished harshly not just as adultery but also as incest.Footnote 8

Figure 1 and Figure 1 a. (a) Map of Dutch-Ruled Sri Lanka and specific outtake of the southwestern coast. The areas marked as ‘VOC (post-1766)’, were generally already under Dutch rule, but this map specifically represents the borders after the 1766 conflict with the King of Kandy. © Thijs Hermsen (Humanities Lab, Faculty of Arts, Radboud University).

The ordinance seems clear enough, but the extent to which the Dutch were able to actually implement their rules has been subject to much confusion and debate.Footnote 9 Recent studies of Dutch colonial court proceedings show how judges juggled different legal principles in a context of negotiation with the people involved.Footnote 10 In this article, we will demonstrate that polyandry, in contrast to the cited authors’ claims, was actually rather common during the entire Dutch period and was not effectively persecuted, but more or less tolerated for the sake of peace and profit. Our research is one of the first studies of polyandry based on historical population registrations.Footnote 11

To clarify Dutch policy regarding polyandry, we will go into the complex relation between Church and government and between the Dutch and indigenous legal systems. The first section discusses the position of the Dutch Reformed Church which was an auxiliary to the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) ever since the takeover from the Portuguese in the mid-seventeenth century.Footnote 12 Then, we address how the Church dealt with the enormous gap between Calvinist conceptions of proper marriage and indigenous practices such as polyandry. Next, we show the complex and curious interaction between Roman-Dutch law and Sinhalese customary laws through a specific case brought before the Landraad (Land council) of Colombo. In the fourth section, we turn to the unique thombo registration. Thombos are basically combinations of genealogies, censuses and land registers through which the Dutch – as well as the Portuguese and the Sinhalese kings in the so-called lēkam miti registers before them – tried to manage the traditional tenure system that tied obligatory labour services to the use of particular plots of land.Footnote 13 Because these sources show gender, age, family relations and the civil status of co-residing persons, we can estimate the potential extent in which polyandry occurred. Moreover, in one district the officials actually ignored their own rules against polyandry and noted which men shared a wife, allowing us to contrast the potential with the actual occurrence of polyandry. By way of epilogue, the fifth section discusses changes in marriage legislation under British rule, resulting in the outlawing of polyandry in the entire island in 1860. Still, the practice lingered on which made it possible for eminent ethnographers to study it in the mid-twentieth century. They described it as a flexible, discrete and often temporary solution to family problems.

2. The church, the Company and SriLankan marriage practices

The Dutch church minister Philippus Baldaeus, who lived and worked in northern Sri Lanka from 1657 until 1666, published an authoritative account of the island in 1671. He made a fascinating observation on polyandry:

Incest is so common a Vice among local population, that when Husbands have occasion to leave their Wives for some time, they recommend the Conjugal Duty to be performed by their own Brothers. I remember a certain Woman at Gale, who had Confidence enough to complain of the want of Duty in her Husband's Brother on that account. The like happen'd in my time at Jafnapatam, which had been likely to be punish'd with Death, had not at my Intercession, and in regard of the tender beginnings of Christianity, the same been pass'd by for that time.Footnote 14

When by 1640 the Dutch had conquered the former Portuguese territories, the latter had been present for almost a hundred-forty years. Many inhabitants of the coastal areas had converted to Roman Catholicism and the principle of holy, monogamous and permanent matrimony had been thoroughly introduced. Only monogamous marriages were consecrated in church.Footnote 15 However, there appears to have been no campaign against polyandry. A Portuguese captain who lived in the southwestern part of the island in the first half of the seventeenth century noted that polyandry was the ‘rule’ and that ‘a woman who is married to a husband with a large number of brothers is considered very fortunate, for all toil and cultivate for her and bring whatever they earn to the house and she lives much honored and well supported’.Footnote 16 Judging from the scarce literature, the Portuguese tolerated polyandry among non-Christians and even upheld it in courts.Footnote 17 Perhaps the women described by Baldaeus counted on Dutch leniency towards polyandry as well? Arriving in Ceylon, the Dutch feared that the Roman Catholic population would remain loyal to the Portuguese. Additionally, as Calvinists they despised Roman Catholics more than other religions on the island, such as Buddhism, Hinduism and Islam. Therefore, the Dutch Reformed Church, essentially a Company-State church, focused on converting Roman Catholics first. As part of its strategy, the Church established churches and schools throughout the hinterland of Colombo, Galle and Jaffna. Protestant, indigenous schoolmasters in the village schools taught children to read and write, they between also and registered the population. The villages were inspected yearly by ministers and VOC agents, accompanied by military escorts. This administrative practice resulted in extensive records, such as the school thombos or parish registers, which did not just register baptism, marriage and death, but also school starting and end dates.Footnote 18

With Calvinism, the Dutch also introduced their moral and social repertoires regarding family life, which were upheld by Roman Dutch Law. Already in 1647 an ordinance was published prescribing local Christians to get married in ‘the Christian way’. Protestant marriage was not a sacrament as in the Catholic Church, but nevertheless an important religious ceremony and a significant administrative act. To marry, both parties had to be baptised and be able to prove this in an official document, in order to gain a permit from the Marital Committee. After making their vows to this Committee, they were now considered ‘betrothed’ and had to ‘put up the banns’, which meant that the intended marriage was to be announced in church three Sundays in a row. If after these announcements no objections were made, the marriage was consecrated by a minister and subsequently registered in the church records.

Before receiving approval from the Marital Committee, the bride and groom had to disclose whether they had married someone before and whether there was any blood or affinal relation between them.Footnote 19 This signifies two important pillars of Dutch marital law. Firstly, marriage was explicitly monogamous, according to the interpretation of Scripture. Polygamy was rejected by VOC legislation both in Ceylon and in other Dutch territories in Asia.Footnote 20 Secondly, although Dutch marriage law had fewer ‘forbidden degrees of kinship’ than Catholic canonic law, marriage with a close family member remained ‘incestuous’. Thus, a widow could not marry her brother-in-law. Since polyandrous marriages could never be formalised, they were considered adultery as well as incest.

The Dutch had great difficulty in setting up uniform marriage registration among the baptised Sri Lankans in their colonial territories. They criminalised unregistered unions in several ordinances, and in different degrees. Adultery, ‘concubinage’, unmarried cohabitation, Catholic or Sinhalese marriages all had different penalties assigned to them, varying from fines, banishment and forced labour to the death penalty, although the latter seems never to have been enforced.Footnote 21 They all, moreover, affected the status of the children born from these unions. By denying baptism to children of unregistered couples, the church imposed the Reformed marital norms on the parents. This could be effective, because baptism was a precondition for the enjoyment of certain inheritance and civil rights, as well as eligibility for jobs within the Company.Footnote 22

Throughout villages in the Dutch territories, the Church established churches and schools that served as regional centres of religion and administration, manned by local schoolmasters. The Church and School Councils managing these churches and schools were based in Galle and Colombo and acted as moral courts. The councils could request the presence of baptised Sri Lankans they wanted to interrogate or discipline, but they could also be petitioned by people asking permission for marriage or baptism, demanding change of registration, or seeking mediation in a family conflict. Indeed, their records are replete with cases of cohabitation, which were often solved by having the couple promise to get married and have their children baptised.Footnote 23 Frequently, women claimed their rights and forced a man to recognise their marriage. For example, Susanna de Zilva approached the Colombo School Council in 1779 and requested it to force Don Joan, her partner of eighteen years and father of her two children, to recognise her as his lawful wife.Footnote 24 This moral and social intervention by the Church was not legally binding but was often used as a mediating institution. In this case, Susanna successfully levered its negotiating power against her partner.

In contrast to cohabitation, very few cases of polyandry made it to the Church or School Councils. In 1742 a Sinhalese mohandiram, a local colonial official who had been baptised in the Dutch church, was brought before the School Council of Galle because he wanted to let his younger brother marry his wife, with whom he already had two children.Footnote 25 The Council was outraged and considered this behaviour to bring shame to the Calvinist faith. In order to set an example, the case was forwarded to the official Court.Footnote 26

The mohandiram's case also points to the Church's ignorance of the private lives of Christians, even the elite ones. Many Christians devised strategies to avoid regulations. In one case involving polygyny, a man legally married his second wife after his official spouse died. In the school thombo he was simply registered as a remarried widower.Footnote 27 Registering only one of the partners could be a strategy to avoid penalties of unlawful cohabitation and still secure inheritance rights in Dutch registration. While this strategy still imposed the idea of a ‘first’ or primary partner, it was a way for people to engage in both Sinhalese and Dutch matrimonial repertoires.

The moral behaviour of the baptised population concerned the Church and School councils, even though Dutch ignorance was compounded by confusion. Many reports on the schools and churches in the countryside mention adultery, cohabitation, and the general bad moral state of the local population.Footnote 28 In these reports, terms such as concubinage and adultery are used loosely and almost interchangeably. They were also referred to as ‘married in the Sinhalese way’ or massebaddoe, possibly a term inherited from the Portuguese, referring to cohabitation without an officially registered marriage.Footnote 29 Cases of Sinhalese cohabitation were often perceived as promiscuous concubinage. In his report of his visitation in Dickwella, a Dutch minister describes a schoolmaster's alleged adultery with another man's ‘mistress’, resulting in a beating of the schoolmaster by the latter man's brother.Footnote 30 Was this woman the second or unregistered wife? Was she also the wife of the brother, or was the brother simply concerned for his brother's honour? A case like this remains unclear, as it is uncertain how the words used by the minister – concubine, adultery – would have been explained to him in Sinhala. Because of these interchangeable terms, it is difficult to distinguish whether any of these cases actually referred to polyandry, and whether the Dutch properly understood the family relations they referred to in these minutes, court cases and visitation reports.

The Church also struggled to enforce its disciplinary efforts since many Sri Lankans might be baptised, but often remained engaged in Sri Lankan moral and spiritual repertoires, such as Buddhism and astrology.Footnote 31 Although Sinhalese Buddhism did not prescribe practical marriage policies, the Dutch regarded the Buddhist, religious elite as moral authorities on marital practices. In 1771, Governor of Ceylon Falck was interested in among others marital traditions in Sri Lanka and the moral ideas behind them. He ordered a report on the rules and customs of the Kingdom of Kandy.Footnote 32 Falck's informants were, not coincidentally, Kandyan, Buddhist monks. One of the questions was ‘If where there are a number of brothers, one of them marries, can the rest with the knowledge of each other, have intercourse with the married brother's wife? and whether such a practice is reckoned proper, amongst the Cingalese?’ The monks answered, somewhat diplomatically:

Neither with nor without the knowledge of each other are they permitted to have any undue intercourse with the married brother's wife: such a practice is not only looked upon, amongst the Cingalese, as extremely improper, but it is likewise considered by them as a heinous crime. Notwithstanding this, it must however be acknowledged, that there are some foolish men amongst whom this disreputable custom does prevail.Footnote 33

It is not clear what Falck intended with this report and how we should interpret the monks’ answer. The monks seem to indicate that the practice of polyandry was not unproblematic within Sinhalese culture. Their unease could very well show the discrepancy between Kandyan high court culture and localised Sinhalese practices. From the mid-eighteenth century onward, a Buddhist revival was taking place in Kandy, partially incited by Theravāda Buddhist monks from Siam, contemporary Thailand. Blackburn, among others Blackburn has argued how this change in Buddhism was the result of a much broader movement than simply the influence of European interaction. It transformed not only the monastic communities but also the position and function of Buddhism in lay society.Footnote 34 According to the Dutch version of the arrival of the Thai monks, this transformation also affected Sinhalese marital practices. A report describes how the first monk who had ‘arrived in Kandia from Siam after having demonstrated to the king the odious and wicked nature of this sin managed to have it banned by imperial decree’.Footnote 35 This report may have encouraged governor Falck to issue the ordinance against ‘crimes of all sorts’ in 1773 (see Introduction). There are no other contemporary references to the Kandyan decree or discussion, but the report suggests either that the Dutch assumed a Thai Buddhist monk must have shared their aversion of polyandry, which would support their own policy, or that the influence of new cultural repertoires did create tensions between the Thai delegation and existing Kandyan rule.

The 1773 ordinance by governor Falck shows the Dutch preoccupation with regulating moral behavior and religious practice on the village level. Nonetheless, the Church realised that this approach had not been fruitful in many areas, especially those further away from the coast where its influence was less than marginal. Thus, we find a completely different approach in 1793, when the Church appointed a catechist for the Hapitigam district. The instructions to the catechist Johannes Perera were to visit each village and to stay there for a couple of days, as long as he could make himself useful and was accepted by the villagers. He was advised during his visits ‘by way of conversation more than as a schoolmaster to convey in a friendly and engaging manner the truths … in order to soften and improve the manners of the people as much as possible’. This gentle approach was an experiment to spread Christianity, but subsequently ‘improving the manners’ of those converted was just as important. Apparently, this was particularly the case for Hapitigam, because:

the inhabitants … still live according to heathen ways, and especially regarding marriage many follow the Kandyan custom according to which a woman sometimes lives with several brothers, which, apart from many good reasons that advise to gently let it pass out of use, slows down the population [translation done by the authors].Footnote 36

Interestingly, the Church's concern with polyandry seems to be about population growth as much as about morality. The discussion on polyandry and population growth was apparently part of European discourse, as a similar argument appears around the same time in the reflections of Malthus on Tibet and India.Footnote 37 Population growth ensured tax revenue and steady supply of labour for the Company. By appealing to the economic interests of the Company the Church seemed to have found a way to fund its latest missionary project.

3. Polyandry and legal practices: a case study

Despite the harsh official ordinances, polyandry did not result in criminal prosecution.Footnote 38 Scholars of Sri Lankan history have identified significant discrepancies between theory and practice regarding law and local customs in the Dutch colonial period.Footnote 39 Because Sinhalese customs were never formally documented by the VOC, they were negotiable and as such a site of contestation between local litigants and the Land Council's (Landraad) councilors.Footnote 40

If the VOC was not really interested in imposing monogamous marriage on the population, how did they deal with the practical complications arising from polyandry? Non-recognised marriages could affect inheritance, and this, in turn, had implications for the duties and responsibilities vis-à-vis the Company. To answer this question, we will look at how polyandry was approached by both local litigants and the Landraad's ‘mixed’ court of both indigenous and European councilors. The Landraad was primarily concerned with local matters and conflicts. Its direct dealings with local communities made it likely that officials encountered polyandry on a regular basis.

In a sample of 33 court cases,Footnote 41 polygamy played an indirect role in at least three. One of them concerned fraternal polyandry. The plaintiff in this case was Rajepakse Pattirege Batjo Appoe, who was identified in the Landraad's records as a Sinhalese mayorāl (village headman) from Biyanwila.Footnote 42 Sometime in the fall of 1775 he had written a letter to the newly appointed provincial chief and the Landraad's principal councilor, the disāva.Footnote 43 He wrote that upon his father's death his father's brother had married his – Batjo's – mother, and thereby claimed all the lands belonging to Batjo's family. When Batjo was old enough he had addressed the local regional chief, the mudaliyār, to claim his share of the family's land. The mudaliyār had sent a small fellowship of his commissioners, which were often high-ranking locals who represented the mudaliyār as envoys, to investigate the case. They decided to split the land between Batjo and his uncle. Since the land at some point had been used as collateral in a loan, Batjo would be allotted half of the land if he would pay off half of the debt that was attached to the land. It had taken Batjo several years to fulfil his end of the deal, but not long after he had finally done so, his uncle's two sons – thus his cousins or rather half-brothers as they shared the same mother – approached Batjo. They claimed that the land that was back then split between Batjo's uncle and Batjo himself should now be split into three shares because the three of them were equally proper heirs. Desperately, Batjo appealed to the same mudaliyār, as well as the then disāva, to reject his half-brothers’ claims. According to Batjo both officials had maintained that the contested share of the land was in fact Batjo's, but the half-brothers had nevertheless continued to plague Batjo regarding the ownership of the land. In 1775, therefore, he had written to the new disāva to put an end to this conflict. The case was opened by the Landraad in the same year.

So far, this case does not seem to differ much from other land disputes one encounters in the Landraad archives. The crux lies, however, in the half-brothers’ response and their perspective on the relationship their collective mother had with Batjo's father and their father, Batjo's uncle. In their letter to the Landraad, the two brothers introduced themselves as Rajepakse Pattirege Mattheis appoe and Rajepakse Hatjan appoe – both inhabitants from Biyanwila.Footnote 44 Mattheis and Hatjan stated that while their mother had indeed been married ‘according to the heathen way’ – meaning, not registered by the Church – to the man Batjo described as his father, she went to live with that man's three brothers after his death. According to Mattheis and Hatjan, it was not until their mother started living with these brothers that she birthed Batjo, Mattheis, Hatjan and two daughters. They provided an extract of a 1770 thombo entry in which it was recorded that the eldest of the three brothers was the father of all these children and the principal owner of the family's lands.Footnote 45 Hatjan and Mattheis initially based their claim on the land on the thombo entry, pointing out that in the register all three brothers were recorded as equal inheritors of the supposed father. However, this was about to change.

It is telling that in his initial correspondence with a colonial institution, Batjo did not mention that his mother went to live with three of his uncles, rather than one, whereas his (half-) brothers did, but left out whether she had a relationship with all three of them or not. At the same time, the thombo extract showed nothing but a nuclear family. Possibly, both parties were hesitant to mention this relationship fearing legal consequences of polyandry. However, Mattheis and Hatjan's tactic changed in their later communications with the Landraad, especially after they took on the help of an (European) attorney. A later statement, written by the attorney in the name of the two brothers, declared that all three men who lived with both parties’ mother were in fact simultaneously in a relationship with her according to the ‘old Sinhalese tradition’.Footnote 46 According to the two defendants, Batjo, Mattheis and Hatjan were all children from this relationship. Furthermore, according to this custom the land had to be divided by them, since they were equally sons of the three men and their mother. And so, in a drastic turn of events, the polyandrous relationship of both parties’ mother with three brothers was suddenly used as a legal tool. Mattheis and Hatjan had witnesses come to the Landraad to testify that their mother indeed procured the children with the three brothers in one union. Batjo's witnesses had initially just underlined Batjo's statement that he was the sole surviving child of his father and only after his father's death his mother married ‘in the Sinhalese manner’ with Batjo's uncle – who then conceived Mattheis and Hatjan. However, during an interrogation by the defendants’ attorney, these testimonies were challenged. The attorney got Batjo's witnesses to admit that it was indeed a Sinhalese practice to have several brothers engaged in a relationship with one woman.Footnote 47 They now also confirmed that Batjo, Mattheis and Hatjan's mother had lived with three brothers of her late husband, rather than just one. Moreover, the witnesses concurred that it was generally impossible in these relationships to indicate which child belonged to which father and that therefore such children were always seen as the brothers’ collective offspring. One witness testified that the mother would know, but that such a distinction between fathers was rarely made. While Batjo's witnesses tried to maintain that Batjo's situation was different, even though they concurred that usually in polyandrous relationships the children would not know their exact father, the attorney had made his point by sowing doubts about Batjo's claims about his father.

From this interrogation onwards, the case started to swing in favour of the defendants, but, unfortunately, it ended rather anticlimactically as both parties came to an understanding before the Landraad reached a verdict. The closing argument of the defendant's attorney repeated that the children should be seen as the offspring of all fathers and thus should split the family's entire inheritance equally.Footnote 48 Therefore, Batjo could not claim one specific share of the land for himself just because he believed he was the son of only one of the brothers. Upon that statement the defendant party offered to settle if Batjo agreed to a division in three parts. Considering the Landraad ended the case there, on 24 February 1776, it seems that Batjo indeed decided to settle.

This case study gives us several clues. Firstly, the statements made by the witnesses suggests that at least in Hapitigam in 1775, fraternal polyandry was regarded as an old Sinhalese custom with clear implications for inheritance and the division of estates. Secondly, although both parties in this case were at first reluctant to openly confess their family's history of polyandry to the colonial court, they did not perceive it as something that could lead to a negative verdict. Even more so since the defendant party began to argue that it was an ancient custom after they had hired an attorney. If a European attorney, experienced in navigating the colonial legal apparatus, felt it was tactically useful to emphasise the polyandry custom, we can assume that customary law overrode official assertions of illegality of polyandry. Thirdly, nowhere in the Landraad's records of this case is there any sign that its commissioners commented negatively on the practice of polyandry. Towards the end of the case the party of Mattheis and Hatjan, who were the ones ‘promoting’ their family's polyandrous background, seemed to be gaining ground. This case study confirms that in the colonial courtroom the custom of polyandry was just as negotiable as other socio-cultural, tenurial and conjugal practices.

4. Counting polyandrous unions

Perhaps it is no coincidence that most of the references discussed above relate to the frontier region of Hapitigam, close to the Kandyan border, where the presence of the Church was limited. What can we say about regional differences and change over time in the actual occurrence of polyandry? For answers, we turn to the unique population registers which have survived from the Dutch colonial period. Following pre-colonial and Portuguese practices, these thombos were created to keep track of land tenure and ownership as land was tied to heritable labour services based on one's caste or communal background, to be performed for the Company. The ancestral lands or paravēni were divided among all children, who held individual titles – in other words the land was not held in joint ownership. Marriage was predominantly patrilocal (a wife joining her husband's family) but the uxorilocal form, called binna was also possible, in which a daughter brought in a husband (see also Box 1 below).Footnote 49 The thombos describe these groups of agnatically related people, their plots of land, their caste status and their labour duties.

It took the Dutch a long time to understand, copy and extend the Sinhalese and Portuguese registration systems. Although Dutch thombo registration followed general prescriptions, the lay-out, categories and variables differ across regions and periods, which suggests that local registrars had some leeway to follow their own interpretations and experiment with registration styles. Recently, the thombos of the Galle district from 1695/96 have resurfaced and we were able to inspect part of them.Footnote 50 They cover about 150 villages spread along the coast and in the rural hinterland to the north of the port city of Galle. These thombos appear to list people by coresidential unit within family estates often consisting of several such units. The average size of the units (dwellings) in Galle is 4.4 persons (N = 6740 persons, see also below). For Colombo province we used the ‘1760’ (compiled during 1757–1761) editions of the rural Kōralēs of Siyane (Hina) and Hapitigam. Furthermore, we can include the 1770 thombos (compiled during 1767–1768) of Negombo, one of the main ports on the southwestern coast. These thombos only list persons per family estate, but still include name, age, gender and relation to the head. As they focus on the genealogical structure of the family group (see example in Box 1), they do not allow us to reconstruct the composition of separate dwellings.Footnote 51

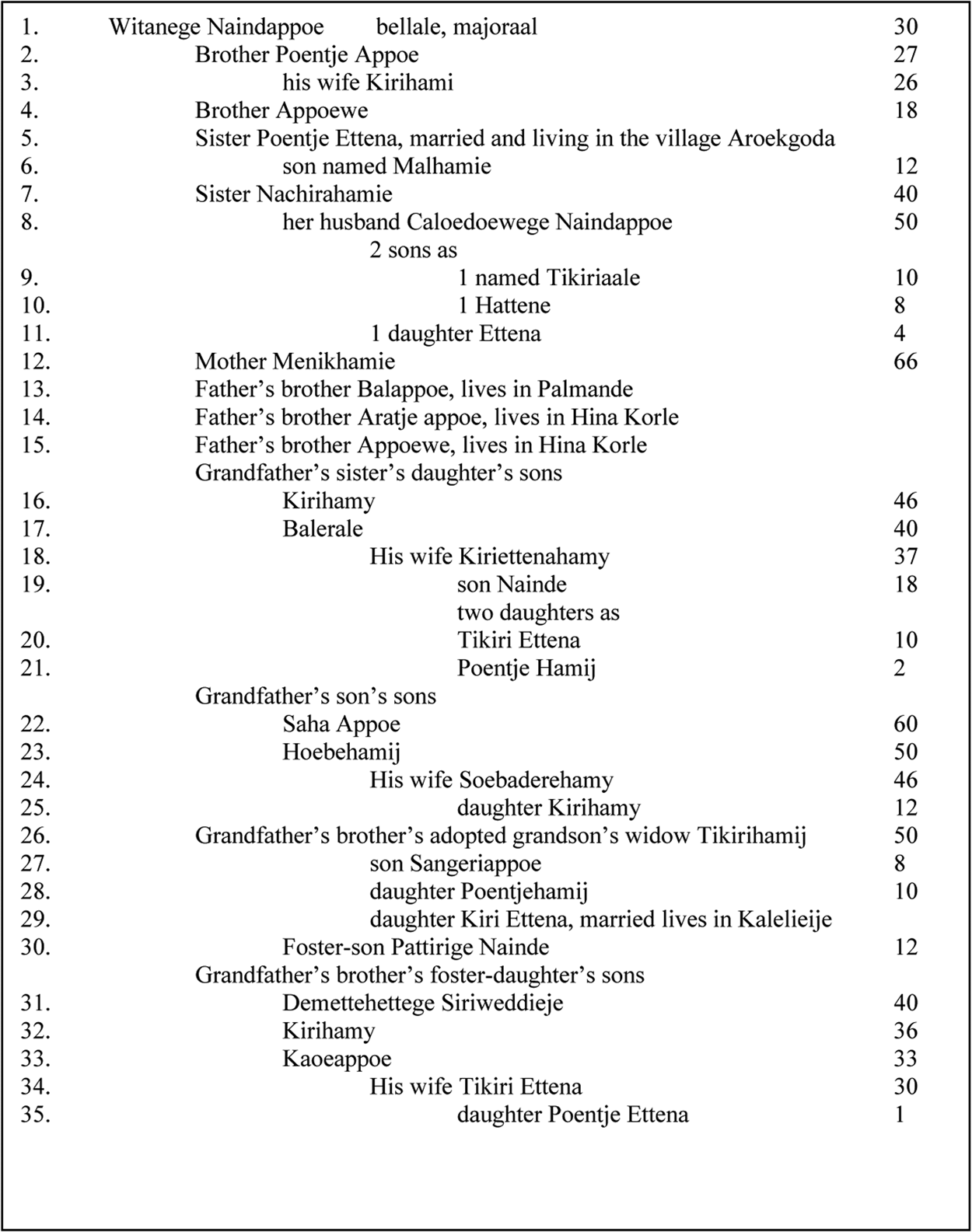

Box 1. The family group of Witanege Naindappoe, Pohonnaruwa, Udugaha Pattu in Hapitigam Kōralē, 1760.

Clearly, the seventeenth and eighteenth century thombos are not comparable to modern censuses or surveys: we need to work around their complexities, uncertainties and, at times, contradictions. In the four selected regions, all thombos had a slightly different structure, implying we need to adjust our estimation of polyandry to each region. But how to estimate the occurrence of polyandry? Ethnographic evidence suggests that polyandrous brothers pooled their property, co-resided with their joint wife in a single dwelling and shared the meals.Footnote 52 The thombos for Galle in 1695/96 show separate dwellings as well as the plots belonging to their residents. But the other thombos do not describe individual dwellings. Our first step therefore is to estimate the frequency of potentially polyandrous unions, or groups of brothers with one wife among them. However, such a frequency count would be meaningless without a denominator: the total number of co-residing adult brothers. We propose a conservative estimation based on the following rules. First, we define ‘brother groups’ as brothers living on the family compound with at least two of them aged twenty or older. This threshold reflects the low percentage of married men under twenty and yields a conservative estimate of polyandry.Footnote 53 Next, we calculate the number of ‘potentially polyandrous unions’ by subtracting the groups of brothers who were either all unmarried (or widowed), or all currently married to a wife of their own.

We apply this method to the thombo registration of all four regions. Brother groups were found among the sons of the head, or the head and his brothers, or his cousins and nephews. Up to four adult brother clusters can be found in large family groups, as is shown in the following example from the village of Pohonnaruwa, Udugaha Pattu (subdistrict) in the Hapitigam Kōralē, 1760.Footnote 54 The family head Witanege Naindappoe, and by consequence his family, belonged to the dominant agricultural caste of the bellale, and he is described as majoraal (mayorāl) or village headman.Footnote 55 He appears to be unmarried. In principle, he could be a widower although there are no children assigned to him. It is quite possible that he shares the woman Kirihami with his brother Poentje Appoe and perhaps the younger brother Appoewe as well. Inspection of this family group yields four groups of potentially polyandrous brothers: the first consisting of 1, 2, and 4; the second consisting of 16 and 17, the third of 22 and 23, and the fourth of 31, 32 and 33.

Fortunately, we have two ways to corroborate our approach. For Galle in 1695/6 we can check how many of these ‘potentially polyandrous’ brothers actually lived in the same dwelling. An even better corroboration is offered by the divergent registration of thombos in Mende Pattu in Hina Kōralē. Here, officials explicitly noted that a specific woman was the joint wife of two (occasionally three) brothers. Again, we can compare this to our number of potentially polyandrous brothers. In this way, we can arrive at a very rough estimate of the incidence of polyandry in the Sri Lankan coastal regions during the colonial era, while circumventing the fact that most thombo commissioners did not record such relationships.

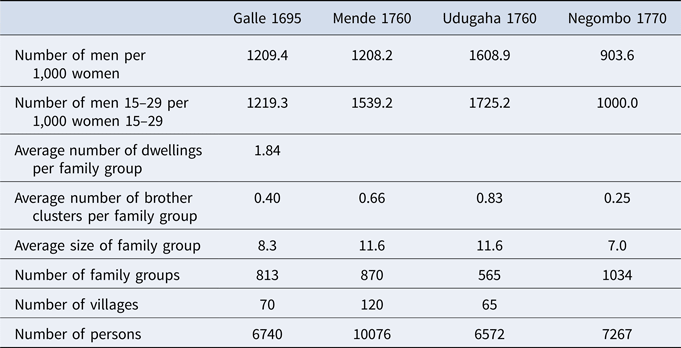

The thombos of the four regions are entered in databases, which give information on more than 30,000 persons listed by their family group.Footnote 56 High sex ratios are sometimes associated with polyandry.Footnote 57 In Table 1 we see that in Galle in 1695, Mende in 1760 and Uduhaga in 1760 there was a clear numerical preponderance of men over women. But in Negombo there appears to have been a shortage of men. If we focus on the ages 15-29 and on persons actually living in the described villages, the lack of women stands out even stronger, especially in Udugaha. A recent study using the same databases noted a low number of registered children in Udugaha between 1756–1768, which was probably caused by a high level of female infanticide. This could be deduced from sex ratios by gender configuration of offspring. It was also found in Mende Pattu, where the discrepancy was less extreme.Footnote 58

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of four selected regions in Southwestern Sri Lanka

Sources: see note 56.

The table also shows differences in the composition of the family groups. The inland regions where people almost solely relied on agriculture have larger family groups, including more brother clusters than in Galle and Negombo. The variation in composition of family groups is very large. This should not surprise us for several reasons. First, it is likely the result of demographic processes, which could also differ by region. Levels of fertility and mortality determine the possibility for a number of brothers to be born and to reach adulthood. Various contemporary observations have noted the small family size of the Sinhalese, possibly related to prolonged breastfeeding.Footnote 59 The Englishman Knox, who had been detained in Kandy for a long period in the seventeenth century, hinted at contraception: ‘And for the matter of being with Child, which many of them do not desire, they very exquisitely can prevent the same’.Footnote 60 On the other hand, infant mortality rates were high.Footnote 61 Second, the question is whether the sons were able to stay on the ancestral land, which was determined by the family groups’ demographic history, but also by social and political pressures. In the earlier-introduced example (see Box 1), the head and his brothers had to share the family's paravēni lands with quite distant kin resulting from decisions of previous generations, for example the head's great-uncle's decision to raise a foster-daughter. Thus, an option could be to leave the family land, as the head's three uncles had done. This, however, could be problematic as land was not readily available and traditional methods of acquiring additional plots for agriculture (such as slash-and-burn agriculture or chena) were significantly hampered by the Dutch out of fear of losing cinnamon trees that were growing in the wild.Footnote 62 Additionally, out-marriage was regulated by local customs – particularly surrounding caste and social status – and by the Dutch colonial state trying to exploit caste-bound labour.Footnote 63 Finally, for brothers deciding to stay and to join forces as co-husbands, marriage options were limited by economic imperatives. Their combined shares in the paravēni should suffice to support one wife and one set of children, neither more nor less. All these factors could push a group of male family members (most commonly siblings) to polyandry.

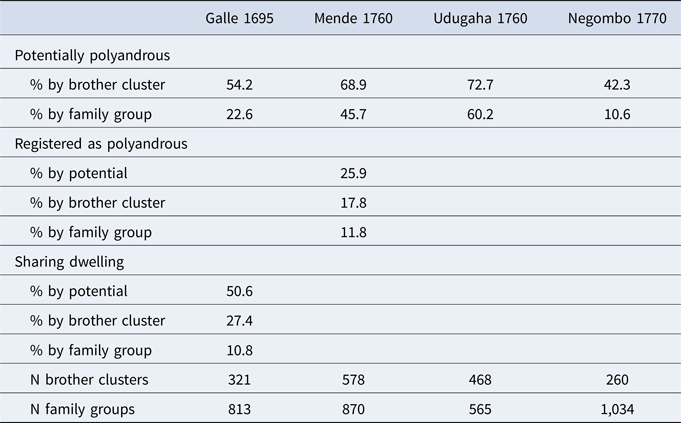

Next, we follow the approach outlined above and count potentially polyandrous unions – or groups of adult brothers with at least one, but not all, of them officially married. Such unions seem to be especially numerous in the inland regions. In Udugaha in 1760, almost three quarters of brother clusters could be described as potentially polyandrous, and such unions were to be found in 60% of family groups. Negombo, with its large numbers of Christian Sinhalese, Moors and European Company staff and their families, counted fewer brother groups (see Table 1). Among these brother groups there were fewer combinations of married and unmarried brothers.

How many of these potentially polyandrous unions were truly polyandrous? The best clue comes from the unique registration style in Mende Pattu. Table 2 shows that a quarter of the potentially polyandrous brother groups in this district were actually registered as such. We do not know why the thombo officials in this district decided to register polyandry, thus giving some form of legitimacy to a relationship that contravened all Dutch laws. We do not even know whether they were consistent in this notation across the district. In fact, among the first 2,500 (out of 10,076 registered persons), not a single polyandrous union was recorded, although there were plenty of potential ones. If we skip those first 2,500 records, the share of registered polyandrous brothers rises to 32%. The Mende thombos also make clear that, indeed, fraternal polyandry of two brothers was the dominant pattern. In only one case out of 102, we find three brothers sharing a wife. But apart from 102 brother cases, we find 9 cases of cousins or other kin combinations. This implies that 8.0% of adult men and 5.5% of adult women lived in some form of polyandry in this area.Footnote 64 If we discard the first 2,500 records without evidence of polyandry, we arrive at respectively 10.6% (N = 2,094) and 7.2% (N = 1,528). Slightly puzzling is the mentioning of brothers-in-law or sons-in-law of the head sharing a wife. We have not included them in the table, as we do not know whether they were brothers to each other.

Table 2. Estimated prevalence of fraternal polyandrous unions in four selected regions, Southwestern Sri Lanka

The early thombo registration in Galle offers another opportunity to estimate polyandry by looking at adult brothers actually sharing a dwelling. Table 2 shows that half of the potentially polyandrous brothers in Galle province in 1695/6 lived together in the same dwelling. The Galle thombos also – uniquely – mention attendance of children at the Protestant schools. Although education for baptised children of both sexes was compulsory, only about a third of baptised children actually attended school.Footnote 65 When we compare school attendance of children from families with polyandrous unions to those without such unions we see no difference: 17% of the boys went to school in non-polyandrous families (N = 1,630 boys), and also 17% of boys in polyandrous families (N = 166). The figures for the girls are, respectively 7% (N = 1,241) and 6% (N = 98).Footnote 66 We can conclude that polyandry did not preclude baptism nor school attendance, and that, conversely, the schoolmasters did not reject pupils from ‘immoral’ families.

What does all this tell us about the overall incidence of polyandry? We can safely assume that about a quarter to half of all potentially polyandrous brothers were indeed living in a polyandrous union. We can now proceed to a recalculation of Table 2. In Galle in 1695/6 potentially polyandrous unions could be found in 22.6% of family groups. This percentage can be recalculated as actually polyandrous unions in 5.7–11.3% of family groups (25–50% of 22.6). In Mende in 1760 we already know it is 11.3% (or 18% if the first 2,500 records are discounted); in Udugaha in 1760 it is no less than 15–30%, and in Negombo it is just 2.7–5.3%. Thus, during the Dutch period, polyandry was quite common in the Lowlands, especially in the rural areas bordering on Kandy. But it was certainly less frequent in the immediate coastal regions which had been under colonial influence the longest. We can see this in the port of Negombo of course, but also in the Galle district. Here, 7.6% of families living directly on the coast (N = 237) contained polyandrous unions versus 12.1% of families in the interior villages (= 576). This, however, does not necessarily imply this was a direct effect of colonial policy or cultural influence. Coastal communities were often engaged in different occupations, in contrast to the hinterlands where subsistence agriculture was predominant. Moreover, or subsequently, (caste) demographics were different in such regions as well. Both are possible indicators that different ways of living were already present between littoral and inland populations for a longer duration of time,Footnote 67 and further establish that polyandry was mostly present amongst agricultural families.

Our data do not allow us to trace changes over time, but it is clear that the practice of polyandry had persisted well into the eighteenth century. It tended to be ignored or even, perhaps grudgingly, accepted by the colonial officials.

5. Epilogue: polyandry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

In 1795, Dutch Ceylon fell into British hands, and they made it a crown colony in 1802. By 1815, they had also conquered the former independent Kingdom of Kandy. The British stipulated that in the former Dutch regions the existing laws would be upheld, whereas in Kandy customary laws were to be followed, which were subsequently codified. We have seen in the introductory section that several authors assumed the Portuguese and the Dutch had effectively stamped out polyandry in the maritime provinces. This supposition possibly stems from the confusion regarding the relation between Dutch official law and the customary, uncodified, laws of the Sinhalese. Several experts claim that, in practice, customary law had held precedence, unless the law was ‘silent or inapplicable’.Footnote 68 Indeed, we have seen in section 3 how a European attorney actually invoked these customary laws to plead the legitimacy of polyandry.Footnote 69 However, the British assumed from the start that the maritime provinces had been governed according to Roman-Dutch law. Already in 1822, they ordered the re-introduction of the school thombos, not just for Christians but for the entire population of the maritime provinces. The pre-eminence of Roman Dutch Law was codified in a charter of 1831, and an ordinance of 1847 specified its prohibited degrees of marriage, minimal ages of parties, and grounds for divorce. Finally, in 1861 Roman-Dutch law was proclaimed as binding for the entire island.Footnote 70 This paradoxical legal situation has been summarised nicely by Jayawardene: ‘[The Dutch] introduced the Roman-Dutch Law to Ceylon; but it is the English… who established it amongst the Singhalese, who made it the law of the land’.Footnote 71

We surmise that the more stringent application of Roman-Dutch laws and the extension of marriage registration raised more obstacles for families in the coastal areas considering a polyandrous union. As such a marriage was not legal, children could not inherit from their second father. What about the interior? The codified Kandyan laws contained all kinds of stipulations on how inheritances from joint husbands were to be divided. But in the 1850s a remarkable development took place. In 1855, Governor Ward received a petition from the Chiefs of Kandy, ‘praying for the abolition by legislation of polygamy and polyandry’. The plea was repeated twice in 1858, finally to be picked up by the rather confused British, who proceeded in 1859 to outlaw polygamy and divorce by mutual consent and to make registered monogamous marriage the only legal form. Why did the elites turn against their own customs and why did they offer the British this opportunity to ‘civilise’ the Sinhalese? Some scholars exhort us to read between the lines of the petitions. They claim that this elite group of landowners wanted a ‘reform’ of marriage because they aimed to reduce divorced and widowed women's customary claims on lands of their parents, which were generally exploited by their brothers. Land transactions and setting up large plantations required simplified marriage and inheritance laws, but this was cloaked in an attack on polygamy, a bait which the British took.Footnote 72 Thus, the British imposed a European concept of marriage on the Kandyan population, which immediately caused a flurry of legal actions as all unregistered marriages – let alone polygamous – were now deemed illegal. Berwick, the critical judge of Colombo, aptly called the 1859 Ordinance a ‘bitter gift of bastardy’.Footnote 73

Even though polyandry could be punished by up to three years of hard labour, the practice persisted until well into the twentieth century, albeit in dwindling numbers. Therefore, it was still possible for the ethnographers who observed village life in the mountainous interior in the 1950s to study existing polyandrous relations or collect reminiscences of past such relations. For instance, the people of Udumulla in eastern Sri Lanka evaluated polyandry positively: ‘It is very good for all. The woman gets food from each husband, and they all have more… These people do not need to hide the arrangement, there is nothing to be ashamed of’.Footnote 74 The ethnographic descriptions often emphasise the practical and quite harmonious nature of the polyandrous arrangement, which in one area was even named ‘living in one peace’.Footnote 75 Why then did it disappear?

The only extensive fieldwork on polyandry was done by Tambiah in a remote rural region in the late 1950s. He concluded that it was mostly a practical solution to an unfavorable man-land ratio.Footnote 76 When the inherited plots were too small to sustain several families, some brothers would leave and marry uxorilocally (binna), whereas others would share a wife. The practice was also related to slash-and-burn agriculture (chena), where plots of land were cleared in the forest at some distance from home. These plots had to be guarded and this required a second man on the farm. We have already noted in the Introduction that traditional caste-bound labour services (rājakāriya) are seen as a possible origin of polyandry in Sri Lanka.Footnote 77 The Dutch colonisers had intensified some of those services, causing the men involved to be away from home for months at the time.

According to Tambiah's detailed examples, marriage often did not start polyandrous, but a brother was invited to join later, which could also be temporary. For instance, a younger brother was invited when the senior husband became unable to provide for his family, due to a disability. Tambiah also notes that relations between the brothers joined in marriage remained very formal and hierarchical, whereas their relation to their common wife was quite unemotional. He surmises that this behaviour was meant to overcome problems of jealousy.Footnote 78 His case studies give some fascinating insights in the strategies and tensions of polyandrous unions. As most marriages still began informally, the issue often arose of who was to be the ‘official’ husband when the moment came to register the marriage. In one case, the younger brother was chosen, although the older had initiated the relation with the woman, as an ‘insurance against defection on his part’. In another case, the younger brother had started the relation but the invited, older, brother schemed to be the lawful one, eventually using the legal advantage this gave him to alienate his brother from the family land. The case studies also show that quite a few polyandrous cases began with sexual relations between a wife and the brother of her husband, who would then concede to formalise it. Still, there was no ceremony of any kind, and the neighbours simply had to deduce from the regular presence of a brother that a polyandrous union had been formed. According to Tambiah, polyandrous unions could be very unstable, especially when they did not involve brothers or when brothers brought different sets of children (from former marriages) to the union. Finally, Tambiah describes a case of polyandrous brothers moving to their joint wife's family land as her father needed additional labour and the opportunities were better than in their own family group. Probably the instances we found in the Mende thombos of 1760 of polyandrous sons-in-law (see previous section) resemble this case.

The informants often described polyandry as a good solution to deal with shortage of land and temporary absence of men, offering protection for women. But the preferred form of marriage was patrilocal monogamous marriage (diga). However, surviving on the family estates where men were often absent required flexible family formation, including uxorilocal marriage and polyandry.Footnote 79 The ethnographers did not disclose why the practice was abandoned, but we can safely assume that the spread of the ideal model of ‘modern’ marriage undermined it. By the 1950s, polyandry only persisted in very isolated and rural contexts, difficult to reach for both people and the influence of the state. As the twentieth century progressed, such locales became increasingly rare. Economic development made life on the rural family plots less precarious, as alternative sources of income, especially in the cities became available. Last, but not least, the continuous commodification of land coupled with inheritance rules which were themselves conditioned on the registration of monogamous marriage eventually outweighed the practical benefits of sharing the burdens of a household.

6. Conclusion

Polyandry did not disappear in the Sri Lankan territories under Portuguese and Dutch rule. We have found ample traces of the practice in the Dutch colonial population registers of 1695/96 and 1760/1770, suggesting that in rural areas brothers sharing a wife could be found in 10-30% of family compounds. And as late as 1793, the Church sent a missionary to a frontier region where they argued polyandry was common practice. Then why did later authors on the subject claim that polyandry in the coastal regions had disappeared because of persecution? We argue that this results from a misconception of both Dutch rule and of polyandry. First, the nature of Dutch government in the region has often been misunderstood. The prime reason for the Dutch presence was to ensure profits for the Company, and this required a continuous effort to placate local elites and to avoid unrest among the population at large. The Reformed Church, although undoubtedly aspiring to convert and moralise the population, played a secondary role. The ministers and schoolmasters concentrated on baptising and educating large numbers of people, but in many areas lacked the power to fully enforce its marital policies. If anything, Dutch policies to preserve the wild jungles where cinnamon grew by limiting access to arable land for local farmers potentially led to more pressure on land, and subsequently for more peasant families to opt for polyandrous unions.

Second, although Roman-Dutch law was quite clear about what constituted legal and Christian marriage, the law was not always applied to all Sinhalese. In the courts, especially the Land councils, customary law held precedence over Roman Dutch law. We have discussed a polyandry case in which a Dutch lawyer argued that inheritance should follow the local custom. The nature of this situational and negotiated legal pluralism was not understood by the British, who declared Roman-Dutch law as binding.

Thirdly, the claim that polyandry was absent in the Maritime provinces may actually have been correct for the immediate coast, especially the towns. Here, mixed populations of Sinhalese, Dutch, (Hindu) Tamils, (Muslim) traders and slaves lived.Footnote 80 The towns had also been under European and Christian control for a long time, making it unlikely for polyandrous customs to persist. But perhaps the most important reason for a low incidence of polyandry was that urban people did not depend on their inherited lands as much as people in the hinterland. The towns offered alternative sources of income, in work for the Company or in trade, which made family economies less vulnerable when there were ‘too many’ surviving sons. We have also seen that, at least in Negombo, the sex ratio was balanced, which apart from income opportunities made marriage for all brothers more feasible.

Finally, the incidence of polyandry may have been underestimated because of several characteristics of the practice, which was still to be found in Sri Lanka in the mid-twentieth century. At least then, polyandry was a practical solution to a shortage of land inherited by brothers to each raise his own family. Villages were mostly very small, consisting of only a few family compounds each. In each compound, the number of surviving brothers depended on fertility and mortality, and their marriage chances depended on the size of their estate, the possibilities to enlarge it through slash-and-burn (a practice which was, as mentioned above, restricted by the VOC), or to move elsewhere. It is not surprising that the ethnographers did not find polyandry in most villages. Our thombos show precisely the same clustered pattern. Villages with small family compounds, consisting of just one or a few nuclear families, often had no polyandrous unions.Footnote 81

Twentieth-century polyandry entailed no ceremony or public announcement and, obviously, no registration which made it invisible to censuses or other government surveys. The official registration of one husband was used with strategic intent by the partners, but it could also lead to internal conflicts. Our church and court records of the eighteenth century also suggests that people effectively managed to hide such relations, and that they knew how to deal with the Dutch rules on registration.

Why did polyandry eventually disappear from Sri Lanka and did the Dutch presence play a role in this at all? Certainly, the imposition of Dutch moral standards and legal codes, albeit in complex interaction with customary law, led to some erosion of polyandry, especially among the Christians on the coast who interacted the most with Dutch officials. But the erosion was accelerated when the British declared Roman-Dutch law superior to customary law, when they extended formal registration of marriage and, finally, when they outlawed polyandry. Possibly, changes in Sinhalese Buddhism also played a role. But probably most important was the perception of the people that registered marriages made land transactions easier. The rights that came with registration were already clearly visible in the Dutch period, when people became quite eager to be baptised and included in the thombos.Footnote 82 The legal benefits of registration were polyandry's undoing.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declare none.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the anonymous reviewers for their thorough and insightful comments. This article was partially made possible through the NWO-funded project Colonialism Inside Out: Everyday Experience and Plural Practice in Dutch Institutions in Sri Lanka, 1700–1800 (360-52-230), which was carried out in cooperation between Leiden University and Radboud University Nijmegen. Part of the archival research in Sri Lanka has been financially supported by the Leiden University Fund/Van Walsem Fonds. Special thanks to Sandra Bulten-Pietrzyk for entering the data from the 17th-century Galle thombos, and to the Wolvendaal Church Consistory and the Christian Reformed Church of Sri Lanka for the access to their archives. Special thanks also to Fabian Drixler (Yale University) for sharing his geographical data for the maps.