Despite considerable differences in national wine growing cultures and markets in European countries, a questionable foundation for a common economic market and resistance to compromise during the negotiations, a unified market for wine was created in 1970 under the aegis of the European Community, driven principally by the French government. The Common Wine Policy (CWP) was the last of the major common market organisations originally discussed at the Stresa Conference to be established. As late as 1969 the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), observing the proceedings, believed that persisting, significant differences in national positions meant an integrated European wine market remained far off. Even in announcing the new CWP the next year on 28 April 1970, the European Commission seemed unable to restrain themselves from mentioning that the process had required ‘extremely arduous negotiations’.Footnote 1 The CWP was pushed through because the idea of it was spoken of, even if not justifiably, as the final piece of a unified agricultural policy in the Community, largely as a result of French interests but also because of the symbolic and cultural importance of wine to Europe that member states had acknowledged since the Treaty of Rome in 1957.

The French national government was one of the principal architects of the CWP – in helping to create it, it attempted to decrease its responsibility for France's wine sector by devolving enforcement of the policy upwards to the European Community, and eventually, after the wine crisis of 1975, devolving implementation downwards to vignerons. The French government also created an environment which was conducive to local agitation and mobilisation by encouraging the grouping together of the wine community's leaders and the promotion of both existing groups and the creation of new ones, which was solidified in various new or enhanced laws for agricultural organisations in the 1970s. While this may have happened alongside comparable processes for the milk and cereals industries, the relinquishing of control over this important ‘patriotic industry’ was surprising and unnecessary. It was, however, helpful to a government under continuing financial strain from subsidising table wine producers who were only looking poised to produce more, while on the horizon the drinking of quality wine in lieu of table wineFootnote 2 loomed.

The CWP's mechanisms, as established during those difficult negotiations, laid the foundation for overproduction (the ‘wine lake’) but also ultimately saved troubled French vineyards and set them on a path towards international success, underpinning the eventual European geographical indications regime. This article considers why France sought to relinquish control over a national symbolic industry, covers the difficult and lengthy negotiations in the 1960s in the European Economic Community – paying particular attention to the French role in these negotiations three years preceding agreement – and addresses the wider implications of the policy that finally came about in 1970. This article adds to the study of the development of European and national policy making interactions by considering political decisions made at the European level against cultural contexts and ideas. It considers how the meanings of agriculture, the family farm and the farmer were relevant to conceptions of Europe and Frenchness, and how political elites both used and responded to these meanings in the creation of the Common Wine Policy. It also explicitly considers the European Economic Community (EEC) perspective, which historians like N. Piers Ludlow and Ann-Christina Knudsen have long argued requires examination on its own merits,Footnote 3 by drawing from EEC archives and investigating the policy making processes that occurred at the EEC, moving beyond merely a nation centric focus on what informed those negotiating positions back in member state capitals.

French Wine and French Identity before 1967

The French connection to wine is deeply engrained in the popular sense of self for many French people. Both because wine is a differentiated product, with regional character, and because it is produced in many regions across France, and drunk by inhabitants in all, wine has played a part in bringing together a country composed of distinct pays; it was ‘one of the elements that helped to form the French nation on the foundations of its regional diversity’.Footnote 4 In Roland Barthes's Mythologies, he presents a series of essays on the myths informing contemporary French identity.Footnote 5 His work provides examples and a kind of theoretical framework for how the French use, interpret, develop and ingest (in some cases – as with steak, milk or wine – literally) their modern mythologies. He argues that wine was foundational to French identity and that ‘the universality principle fully applies here, inasmuch as [French] society calls anyone who does not believe in wine by names such as sick, disabled or depraved: it does not comprehend him (in both senses, intellectual and spatial, of the word)’. By contrast, a French person who had ‘the know-how of drinking’ (savoir boire) would be seen as a good and trustworthy citizen, and a known entity. To Barthes, waxing romantic about the importance of wine to the French had been done ‘a thousand times in folklore, proverbs, conversations and Literature’ and ‘this very universality implies a kind of conformism: to believe in wine is a coercive collective act’.

Barthes's evaluations about the importance of this mythology to the French seems borne out by French self-evaluation of their own identity. In a modern study commissioned by the French government as to the components of French identity, which spawned a seven volume publication, the top three were, first, having France as one's birthplace, second, the defence of liberty and, third, speaking French; in close fourth place was being knowledgeable about and drinking wine. To explain what to some readers would have been an unusually high ranking for one specific food product – and given the more universally apparent gravity of the first three, a more superficial indicator of identity to some – the survey's unsurprised authors stated ‘wine is a part of our history; it's what defines us’.Footnote 6 While the French are very attached to their agricultural roots and many different agricultural products, as well as to the way of life that is connected to them, their most emotional attachment is to wine. That the French government relinquished control over it at all showed the intensity of the domestic political disputes that drove their decisions.

If the identity of French people in general was heavily tied up with wine, this was nowhere more intense than the attachment of certain vignerons to their farms, vines and wines, particularly small family farm owners. After all, one might very well wonder why wine has remained the dominant economic force in the Languedoc region, which in the mid-twentieth century was a leading producer of table wine. For this, there are ‘social and psychological as well as economic factors. The Mediterranean vigneron places a high value on viticulture. His ancestors cultivated grapes and made wine centuries before the unprecedented spread of vines in the nineteenth century, and much of his cultural life and his festivities were and still are integrated with the annual routine of the vineyard. There is an attachment to the soil that is deeply embedded in the vigneron's psyche which helps explain why so many of them, despite their impecunious condition, remain on the land.’Footnote 7

The French nation's love of wine sat well alongside state control of agriculture. The French management of wine in the twentieth century was based on a foundation of agricultural exceptionalism and characterised by heavy state control.Footnote 8 The state believed French farms served broader national interests and, as such, should be subject to heavy state intervention if necessary.Footnote 9 The origins of the structure of French government intervention in the twentieth century lay in organising the wartime economy. Intervention subsided for other sectors after 1920 but increased for agriculture with the expansion of ‘legislation on agricultural credit, farm reorganisation, new forms of property rights, agricultural education and the provision of technical and advisory services’.Footnote 10 Through the 1920s and 1930s this state involvement continued apace, and from 1945 onward it expanded considerably. Western European governments began to favour modernisation and technocratic decision making, and growth and investment characterised the years from 1945 until the early 1970s.Footnote 11

The French government's interest in voluntarily and strategically decreasing its role in its domestic wine industry was primarily because subsidies to wine growers were expensive,Footnote 12 and they wanted to relieve themselves of a historically ingrained system which had propped up key national industries at all costs. The French government has had a long history of ‘explicit, assertive, continuous, and comprehensive’Footnote 13 state intervention, particularly with its post-war dirigiste economic policies, reaching its zenith in the late 1960s with the Fifth Plan, whose main objective was assuring the international competitiveness of French firms via government support. In the first few decades of their operation, the Chambers of Agriculture, for which legislation was enacted in 1920, were an advisory and consultative body in the regions; however, their role increased considerably beginning in the 1950s, when they became the ‘prime agencies of state intervention in agriculture, acting as coordinating bodies for structural reform programmes’.Footnote 14 At the end of the 1960s they were responsible for continuing to support the costs and structures of programmes which were ever increasing.

More broadly speaking, costs across the different agricultural sectors – not only in the wine industry – needed to be scaled down. By the 1970s they were becoming prohibitive: the French Ministry of Agriculture's expenditure increased tenfold from 1950 to 1979 with massive spending on rural structural and social programmes.Footnote 15 The wine industry had in many ways been treated by the French national government in the same way as their other national ‘industry champions’. Political scientist Jack Hayward's assertions about the changing pressure and operation of French national industries are reflected in the wine industry: national firms were increasingly losing their market monopoly and national protection; when in deficit, firms that used to have recourse to overt or covert subsidisation were now required to be self-sustaining; and these firms were being pushed to adopt more international strategies by contracting transnational alliances. However, there are two vital differences between the industries Hayward uses to exemplify these trends and the wine industry: first, French wine groups largely had no recourse to international capital markets if the government or national banks were unwilling or unable to help, and, second, whereas other industrial firms were ‘no longer the . . . projections of national identity, so that the sometime national champions of the 1960s have perforce tended to acquire a transnational identity’, the wine industry remained – necessarily, and by choice – rooted in France.Footnote 16

The twentieth century was a time of transformation and upheaval for not only wine growers but for French farmers in general. There were attempts by the Vichy government, and indeed successive French governments, to protect the component of ‘rural idyll’ in the French identity. Mark Cleary's work Peasants, Politicians, and Producers, in its attempts to trace the development of peasants and in particular their organisations relative to the state and capitalism in twentieth-century France, dissolves the myth, stemming from economic generalisation, of ‘rural France . . . as unified [or] monolithic’.Footnote 17 Instead, he contends there were ‘huge spatial and social contrasts’ before the First World War which were widened by both the shifting priorities of the French government and then the European Community.Footnote 18 It is on the topic of the Community that Cleary's otherwise excellent book gives little illumination – despite his repeated suggestions that the Community was important, his discussion of the Community or the Community's impacts, direct or otherwise, on French farmers is limited.

The desire, however, to alleviate the increasing costs and support structures in the wine industry, as in other agricultural industries, ran against several other French ideals that made dismantling or even reducing the state apparatuses that supported table wine a difficult and delicate task. The French government's policy of aménagement du territoire was created to manage French national territory through spatial planning taking into account community, landscape and identity. An essential piece of this work involves preserving ‘a network of agriculturally-oriented villages throughout much of [France]’.Footnote 19 This rather uniquely French state mission was called upon to justify the continuation of state aide for agriculture, and, in particular, for small farmers, which the Midi table wine growers largely were. In this conception of the role of farmers – against the broader imperatives of aménagement – they were not only producing food for the state and playing a role in its economic machinery but were also a part of the fabric of the nation, by being keepers of the rural and traditional ways of life and the guardians and tenders of the landscape. Michel Débatisse, who was president of the National Federation of Agricultural Holders’ Unions (Fédération Nationale des Syndicats d'Exploitants d'Agricoles; FNSEA) from 1971 to 1978, expressed this very sentiment by saying that the role of the farmer needed to be protected by the state for it went beyond food production and security – it was also about ‘the working of the land, the presence of farmers in all regions, a certain conception of the relationship of man to his work, the mixture of the economic and the social . . . which, in my opinion, is a guarantee of not merely economic gain but of continuing to have a certain social fabric’.Footnote 20

Finding a Basis for a Unified European Wine Policy, 1961–7

While there was plenty of earnest talk about the necessity of wine's inclusion in any integrated European agricultural policy in the years following the Stresa Conference in 1958,Footnote 21 serious discussions on how to integrate national wine markets would not occur for many years. However, the Stresa Conference introduced an important mandate which would later require wine policy negotiators to grapple with a moral imperative: the Stresa resolution introduced crucial new concepts such as ‘the importance of the family farm’.Footnote 22 Quick progress on other common markets in the early 1960s left the one for wine quite behind. On 31 May1961 a proposal for a common cereals market was put forward by the European Commission to the European Council, as was one for milk and pig meat. A few months later, in July, there were formal proposals for markets in fruits and vegetables, eggs and poultry meat. But wine policy proposals were delayed, with the European Commission citing concerns over the availability of statistical evidence to understand the scope of what they were dealing with.

Three major events in 1962 changed the course of wine regulations in Europe. First, on 14 January 1962, after the 140-hour ‘agricultural marathon’ of negotiations over the propositions for various integrated markets, the decision to create six agricultural markets was approved. This was an enormous undertaking. European Commissioner for Agriculture Sicco Mansholt and Commission President Walter Hallstein envisioned at this landmark juncture that an eventual wine policy would fall under a lower level of protection relative to the other common market organisations (CMOs), which would see it mostly subject to customs duties and levies on imports. Second, as a preliminary step, European policy makers created regulation with four major provisions, mainly administrative, to lay the foundations for the eventual creation of a common wine policy. Regulation 24/62Footnote 23 established that, first, each country was to create a vineyard register, second, a central authority was to keep track of annual production levels, third, strict rules were to be set regarding quality wines produced in specified regions and, fourth, future estimates of resources and requirements were to be compiled annually. In contrast to this rather minimalist series of measures, the other markets had preparatory arrangements for their upcoming market organisations which were considerably more wide-ranging. For instance, the creation of the milk market was first addressed after Stresa in 1964 with the establishment of Regulation 13/64. This preliminary text already contained detailed plans for a price levy system for imports, as well as pricing mechanisms for the Community support structures, such as how often a threshold price would be established, and even included a timeframe for the abolishment of intra-community tariffs on milk and milk products. Four years later the common market organisation for milk was rendered in full.Footnote 24 There was not a similar trajectory for the wine policy. Third, with the passing of the Evian Accords, Algeria gained independence from France in 1962, resulting in a transition from a France situated in its empire to a France situated in an integrating Europe.Footnote 25 This gave France license to more aggressively try to reduce its intake of Algerian wine.Footnote 26

The French intake of Algerian wine is the result of the success story of the rescue of European vineyards from phylloxera, a parasite that attacked Vitis vinisfera, the European vine species. Phylloxera wiped out an estimated half of the vineyards across the continent and reduced French wine production by three-quarters between 1875 and 1889.Footnote 27 The French government then intensively imported wine from its then-colony Algeria, as well as Spain and Italy, while various cures for the parasite were investigated. The introduction of these imported wines, however, caused a decrease in the price of local wines as a result of cheaper foreign winesFootnote 28 and also added to existing wine quality problems – resulting in the main from issues of adulteration and fraudulent wines – in European wine markets.Footnote 29 In the years after the Second World War, with the phylloxera problem by then well under control and the southern French vineyards recovered, the continued requirement of importing wine from Algeria due to French–Algerian treaties, together with the surplus production of French wine growers, exacerbated the problem of an already saturated French market.Footnote 30 Despite Algeria no longer receiving favoured trade status, Algerian arguments that they had largely planted vineyards to help France were so strongFootnote 31 as to force the French in 1964 to commit to purchasing 39 million hectolitres of wine from 1964 to 1968 to prevent a sudden collapse of the livelihoods of Algerian wine growers.Footnote 32 This was a significant volume given the average total domestic French production of wine through the 1960s was 63 million hectolitres a year.Footnote 33

France was further facing problems of a decrease in wine consumption. According to statistics the United Nations’ FAO had compiled from the beginning of the century, it was clear that in France ‘consumption has constantly decreased’.Footnote 34 Further, the FAO criticised the wine market as a whole in France, using it as a prime example of a country that had still not produced proper ‘control measures and limitation of production’.Footnote 35 It charged France with chronic overproduction and the steady decline in the quality of vineyards in southern France.Footnote 36 The French themselves certainly knew that overproduction was serious and systemic – and this was clear during the CWP negotiations.

France turned to the European Economic Community for a solution, but this was not so easy. The negotiations for the cereals sector took much of the attention of the Commission and Council after the 1962 wine provisions were created – after the May 1961 proposal, discussions progressed quickly, and the Council agreed unanimously with the Commission's proposal on cereals. But while the Council expected to have the market running in July 1962, the inability of Germany to come to an agreement by 1964 with the other members over the fixing of wheat prices meant a long delay on the matter. An unsatisfied President Charles de Gaulle prompted the 1965 ‘Empty Chair Crisis’, which then loomed large over the wine negotiations. In the meantime, France struggled to balance domestic production and consumption, and began to renege on accepting Algerian wine imports.Footnote 37 It was fearful, too, that the process of harmonising wine production practices would threaten ‘the French state's ability to create and safeguard production’.Footnote 38 After a lag of five years, negotiations for a common wine market finally began in earnest in 1967.

Negotiating a Common Wine Market Organisation from 1967

After the establishment of the provisions in 1962, there would not be another major movement towards a unified wine policy until a meeting of the Wine Working Group (Groupe de travail ‘vins’), the Council's group of wine experts which reported to the Special Committee on Agriculture (Comité Spécial Agriculture; CSA). The Group was composed of key decision makers for the Common Agricultural Policy.Footnote 39 The CSA announced that in February 1967 the upcoming Council of Europe meeting would include the first meeting of the Committee of Senior Officials (Comité de Hauts Fonctionnaires)'s sub-committee on wines, at which the Committee of Permanent Representatives (Comité des représentants permanents; COREPER) and the Council wanted to present a unified, coordinated attitude.Footnote 40 This was noteworthy, as the Council was a body with no agricultural remit and yet it was this group that was in part responsible for triggering a new move forward in European agricultural policy. These kinds of external pressures would prove to be vital for keeping up the momentum of the discussions on a unified wine policy.

In June 1967, triggered by the Council of Europe meeting a few months prior, the Commission finally returned to the 1962 regulations that laid down the basic administrative foundations for a common wine market (marché commun viti-vinicole), recalling its propositions for a common wine policy in 1960 based on its belief that a general common market could not work without an integrated wine policy. The Commission admitted that, because of the lack of action since 1962 on a common wine policy, the situation in the Community continued to be characterised by very strong protectionism and divisions between the different national viticultural policies, due to ‘natural and historical’ reasons.Footnote 41 External pressure compelled action: the Council and Commission wanted an agreement before the meeting on 11 December 1967 of the European Council's Committee of Senior Officials for Wine and Spirits (Comité des Hauts Fonctionnaires sur les vins et spiritueux du Conseil de l'Europe).Footnote 42

Similarly, at a Council meeting on 16 July 1969 the German delegation drew attention to the fact that the Six (the term referring to the original EEC member states Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) would each be required to give their definitions on oenological methods at the upcoming meetings on 13 and 19 October 1969 of the International Organisation of Wine and Vine (Organisation internationale de la vigne et du vin; OIV). The OIV was an international intergovernmental organisation dedicated to dealing with scientific and technical aspects of viticulture and viniculture (where viticulture refers to the growing of grape vines and viniculture to that of the knowledge of making wine). The Germans pressed the Council for a resolution, pointing out that the issue that needed to be decided at the OIV meetings corresponded precisely with the decisions that needed to be taken on the Community's proposed wine policy, and that this would be an ideal time to move forward with the latter. At this same meeting, the Groupe de travail vins called to the attention of COREPER the necessity of coordinating the attitude of the Six ahead of the meeting of the Wine Committee of the FAO.Footnote 43

These international meetings were important political chances to demonstrate a consolidated communitarian stance; the members knew that if they could not they would face further threats to their ability to create a unified market. Decisions made at other non-Community organisations that were binding – such as those at OIV, where changes had to be ratified by all its members and all six member states were members – could potentially place unwanted restrictions on decision makers in the Community.

The Commission's proposal for the development of a common wine policy was initially a result of three major lines of thought – that any policy produced should address ‘the adjustment of production and consumption’, that it should undertake to improve the quality of Community wine and that it should harmonise the divergent national legislation. The most serious obstacle to integration was the profound difference between the French and the Italian wine production systems, which became a centrepiece of the Council and Commission negotiations. The French wine system had been strictly organised since the Wine Code (Code du Vin) was adopted in 1936. Through this the French state maintained stringent regulations on planting and regulations aimed at reducing the production of poor quality wines, as well as regularly intervening in the case of pricing issues due to harvest fluctuations. The French also had a rich heritage of agricultural cooperatives, which were significant around this time as they accounted for 42 per cent of total production in France, and 70 per cent of production in the Midi, the largest wine growing region by volume in the world at the time.

The Italian system, in contrast, was ‘marked by a very great liberalism; moreover, the vine being there considered as a colonising plant, its cultivation is largely encouraged, under certain conditions at least’,Footnote 44 as the Italians encouraged the planting of vines and the development of vineyards as a way to improve the living conditions for farmers in poor rural areas. Their wine market produced a large amount, comparable in the 1960s and 1970s to France, but was in its infancy as far as having a modern, national and regulated market was concerned. Most wine produced was consumed in the country and was of table wine quality. In 1963 the Italians developed the Controlled Designation of Origin (Denominazione di Origine Controllata; DOC), in response to the reorganisation required by the Council regulation of the previous year. In 1965, in part due to trade pressure from the French, the Italians enacted policies to counter fraud. But their principal policy aim was to encourage the spread of wine growing as a national economic and social development tool. Both France and Italy wanted to reproduce their national models at the European level, and it would be necessary for decision makers in Brussels to find a compromise between the two different approaches of the Community's two largest wine producers.

By July 1968, a year after negotiations had begun, the fixing of prices had been established for the common markets of milk, beef and veal, sugar, rice, oilseeds, olive oil and cereals, but not for wine. The French complained about the lack of progress, but the gridlock was largely due to their own lack of agreement with many aspects of the proposal. In a detailed special report to the CSA,Footnote 45 the primary argument of the French delegation was this: to maintain balance in the wine market, one ought to control the level of production and the level of imports, which the French insisted could only be effective if at the same time there was a determined push to eliminate and discourage the production of poor quality wines.

The French worried that the Commission's rather open attitude towards the use of distillation in the case of high yields (which is itself an expensive measure) would encourage an ‘intensive production of mediocre wine’.Footnote 46 The French claimed that without efforts to curb the large surpluses sure to rise from new plantings, without certain rules regarding quality standards and limitations around planting, and without sufficient protection of the market and pricing, the result would be disastrous for the Community. The French were concerned for the possible consequences of a liberal policy for the Community as a whole, but this worry also stemmed from an issue closer to home. A policy with no restrictions on planting would have been great trouble for them further down the line with the production trends in France's southern vineyards; even the inclusion of some sort of built-in price support system of a future CWP, which would mean subsidies for the country's farmers, would have been unlikely to adequately abet the situation of further projected rises in production.

The increase of production in both France and Italy over the previous decade was symptomatic of systemic overproduction as a result of domestic welfare policies within both Italy and France, with Italian encouragement of the development of rural areas and the continued French protection of wine growers in the Midi, who produced a great deal of the poor quality table wines against which the French themselves were arguing. (It was, interestingly enough, the Germans who through 1968 and 1969 repeatedly tried to argue that this was the case, and who were rebuffed by the other two.) The French government intentionally wanted to develop a more restrictive policy on planting at Brussels and not in Paris so as to avert in part potential blame from vignerons; the effort of the French government to ‘discourage the cultivation of inferior grapes was a political and not a scientific one: [it was] the need to curb the subsidies that drained the budget of the Ministry of Agriculture’.Footnote 47 Further, pro-Europeanist French Minister of Agriculture Edgard Pisani maintained for his tenure from 1961 to 1966 his desire for the ministry to help ‘integrate agriculture into European and global markets, and champion appellation wine’.Footnote 48 On this last point he was joined by a group of influential ‘appellation leaders, technocrats and public health activists’ who shared a common interest in organising the wine market, promoting geographically indicated wines (very generally, higher quality wines) and reducing the perceived threat of alcoholism. They thereby came together at key junctures of the negotiation process to pressure both the ministry and Eurocrats to create a unified policy that would favour quality wines and reduce overall production.Footnote 49

In response to continued problems with negotiations, a series of CSA meetings in November 1968 were reserved for the wine policy negotiations,Footnote 50 at which the frustrated Germans suggested a simple, basic coordination of national legislation, akin to a customs union (much as Mansholt and Hallstein had originally envisioned in 1962), as a first step for the wine market. Both France and Italy were committed to the process of creating a full, proper CMO; they refused a partial integration, citing the relative importance of wine to their countries and to Community integration as a whole. Domestically, the French faced pressure from wine cooperatives, which had started to become relatively well-organised through the 1960s, and who would have been displeased with a loose, unstructured policy at a time when prices and consumption of table wine were falling. The suggestion by the Commission representative at the meeting that it might become necessary to simply copy and paste the more technocratic models from the organisation of the markets of other major agricultural sectors was ignored by other representatives. Despite the many pressing difficulties, the central line was still that ‘organisation of a common market for wine is indispensable for completing the integration of the agricultural economies of the Six’.Footnote 51

The Politics of Agreeing on Pricing and Production

The problem of reaching agreement on pricing was the major sticking point from November 1968 onward. At the beginning of 1969 an agreement on pricing mechanisms for wine seemed to be out of reach. The model proposed by the Commission at the time was a loose price support system complemented with supplementary price supports, safeguard clauses and a Community tariff. The Germans, along with the Belgian and Dutch representatives, found even this basic system to be too much – they expressed their ‘deep reserve on the mechanisms’ and went on to state they were ‘not convinced of the necessity of taking these measures’.Footnote 52 To the Germans, the measures taken for the wine policy ought to be more ‘of a precautionary character’Footnote 53 than the current Commission proposals. This was at stark odds with the French position: they thought that the system in its current conception was not nearly wide-ranging or incisive enough, was as yet ‘insufficient to achieve the objectives of a common wine-growing policy’,Footnote 54 and further did not contain any steps in the direction of the promotion of quality in the wine industry.

On 15 January 1969 the Secretariat General prepared a summary of the major points of contention amongst delegates regarding the wine negotiations.Footnote 55 The four key issues still requiring resolution were, first, what the guiding objective or objectives of the wine policy ought to be (would it be balancing production and demand, following a policy of quality, or administratively directing production policy?); second, what the links should be between the market organisation, the harmonisation of existing legislation, the regulation of quality wines and the organisation of a market for alcohol more broadly speaking; third, how to arrange the trade regime with non-Community countries; and, fourth, what legal form the market organisation for wine should take (should it be a common market organisation, or, as the Germans continued to suggest, a ‘simple coordination of national bodies’Footnote 56). In addition to this list of difficult conceptual problems, at the top of the fifth year of negotiations was the complex technical problem of how to manage the ‘regularisation of the Community market’, for while all delegations agreed in principle with interventions of some sort, ‘profound differences have however emerged regarding the extent, nature and the character of the anticipated mechanisms’.Footnote 57

At this meeting, the matter of whether overproduction was a potential future problem was heavily debated. The French delegation, supported on this point by the Germans, argued that overproduction was a great possibility and could only be averted with strict Community control emphasising quality of vines and terroirs – this uniquely French word, when applied to wine, encompassed such diverse aspects as geology and climate, such as sun, slope, soil composition and precipitation, and is tied together in a specific locality which gives it a sense of ‘place’. This word is usually used in the context of quality wines. The French were adamant that a system not be designed in which there was ‘an under-protection of quality wines and an over-protection of mediocre wines’.Footnote 58

The French were insistent on this point, as they had been since the beginning of negotiations, for the national mandate issued to them had itself been resolute on the same issue. The French stance during all negotiations was set by the Secretariat General of the Interministerial Committee for European Economic Cooperation Questions (Secrétariat général du comité interministériel pour les questions de coopération économique européenne; SGCI), the Paris based national governmental body that liaised with different relevant French ministries to coordinate the official French line in Community institutions. Even if its detractors claimed it was not particularly transparent – one commentator quipped it was ‘an administrative agency with an unknown role and considerable importance’Footnote 59 – the SGCI, staffed predominantly by those from the Ministry of Finance, was the reason why French coordination and consistency of goals in the European Commission was widely considered the most efficient of the member states.Footnote 60 In fact, it was the strict rule that ‘French ministries were not allowed to accept agendas of meetings in Brussels without the agreement of the SGCI’,Footnote 61 despite the fact that it did not have official decision making powers. The SGCI had most recently set the formal agenda on wine negotiations by stating that delegates were to make three points clear: first, that, given the French overview of their own domestic situation, overproduction was likely and the situation could degenerate quickly – but delegates were instructed to make this point about the Community situation in general (that is to say, they should also argue that this could happen in Italy); second, that production had to be limited at all costs, but this point might have to be made in a nuanced way because the Commission had taken the line along with the Italians that planting should be allowed to continue freely; and, third, that the French delegates were to counter any continued German demands against comprehensive, built-in Community intervention measures in wine with the line that these needed to be ‘Community-wide and obligatory’.Footnote 62

The document urgently noted that ‘the German delegation maintains, on the other hand, that the Council decided, when the Financial Regulation was amended in May 1966, that the common organisation of the wine market would not be financed by the Community’.Footnote 63 This was unacceptable for the French, for their aim was to transfer policy making power, and in particular the hefty and difficult financing of their national wine industry, to the Community institutions. The document pressed delegates to make the point that the May 1966 resolution ‘leaves . . . fully open the possibility of Community funding’.Footnote 64

The Italians argued instead that reaching equilibrium between production and consumption was possible, and that the other delegations were setting a dangerous precedent by trying to limit planting rights, declaring that this would be an attack on Italy's cultural, economic and social sensibilities.Footnote 65 In response, the Commission representative stated that the Commission was not unwilling to adopt temporary ‘binding measures’ to help alleviate an imbalance, but stated that the position of the Commission was that ‘it considered that such a situation of imbalance did not yet exist’.Footnote 66 Finally, the solution the frustrated parties found was to intervene on a case by case basis; this mechanism was unique to the wine market as other similar common markets had automatic interventions.

The negotiations for pricing on the cereals market were infamously complicated as well, and negotiators did not arrive at case by case pricing. Why did this happen in the wine market? There was in part considerable pressure to arrive at a solution quickly and, thereby, more pressure to relinquish national goals in favour of compromise, because the wine market was the last of the original markets left to be unified. The free circulation of wine within the Six was meant to be in effect from November 1969; further to this, earnest and intensive enlargement negotiations were planned for the 1970s, and it was incumbent to have all the markets running before then. This also made the eventual CWP more prone to criticism and open attack because it required incisive ‘hands-on’ action each time pricing became problematic as it could not depend on automatic intervention like other markets.

In early 1969 the situation looked bleak. The Commission and Council sustained a long discussion on the definition of the word ‘wine’. The FAO remarked that the Community's common wine policy as it stood ‘has indeed made very little progress and that major problems remain still to be resolved’.Footnote 67 The Council continued to express doubts about the Commission's proposal, citing problems with the application of appropriate measures for production policy, the character of protectionist import measures and the measures to balance a common wine market. In the midst of these challenges, greater clarity was achieved by splitting issues of concern into general problems and technical problems, which allowed the delegation of in-depth and now extensive technical matters to the Commission and Council's own individual expert wine groups, which had been confusing and laborious for non-specialists to discuss. At the tail end of the previous year, this mandate had been explicitly conferred to the Wine Working Group by the Special Committee for Agriculture at the Group's 25 November 1968 meeting for the purposes of allowing the latter to take charge of making ‘a thorough study of the technical aspects’Footnote 68 of the wine policy proposals. But the real breakthrough, though it came reluctantly, was when Germany helped France and Italy take steps towards a compromise on pricing mechanisms and financial aspects of the CWP in early 1970.

It was not until February 1970 that the Council approved the Commission proposal, announcing that after negotiations which were ‘wearisome, often profitless and largely dominated by a clash of national interests’, they were reaching the end and that the implementation of what would be regulation 816/70 was close at hand. But this they did without particularly satisfying anyone, least of all France, whose desire to keep the Community's vineyard to its current size had been quashed. To get Italian agreement on financing meant France made greater concessions, resulting in a much more liberal regime that allowed both free trade and free production of wine. In mid-April 1970 the process looked like it would fall apart again, during a very stormy meeting in which the Italian proposals to ban the addition of sugar to grape to increase alcoholic content was met with fierce resistance by both the French and Germans, who both used a sugaring process called chaptalisation with some of their bestselling wines.

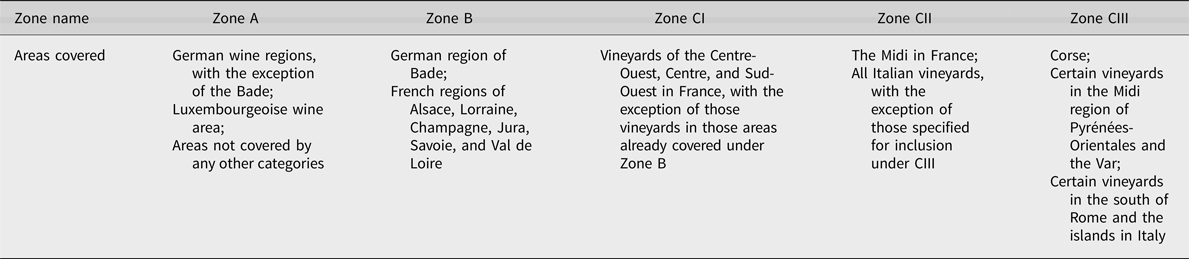

In the end, five major agreement areas were in regulation 816/70 which set down common rules for the organisation in the Community's market in wine. The first was prices and intervention – it was agreed that price fixing would only be done for table wines, and that quality wines would not be subjected to such a process. Rules concerning production and control of planting enshrined the freedom to plant. High import rates were imposed on trade with non-EC countries, as well as more stringent regulations on the type of wine that could be imported. Further to this, blending of EC wines with non-EC wines was strictly banned. The final two rules were about oenological processes and general provisions, such as definitions. One important arrangement was the division of Europe's vineyards into five geographical categories, as outlined in the following table.

Table 1: European Community wine growing zones as set out by Regulation 816/70

The Commission welcomed the birth of the CWP in April 1970 with this announcement: ‘given these different [national] interests, often diametrically opposed, a single approach to the wine market problem was only possible because all sides made considerable concessions. Growers in Italy, France and Germany are bitterly critical of the Council's resolution: they all feel that their own Government has given too much ground. It might be said indeed that everyone is equally dissatisfied, which proves that the agreement by the Ministers is a genuine compromise.’Footnote 69

The Belief in Wine as Part of the European Integration Project

Tracing the arc of the negotiations over the Common Wine Policy reveals both that the pressure to complete the agricultural project brought the French and Italians to a disgruntled compromise on the issue of wine as well as the persistence of parties in seeking a common market structure, despite repeated setbacks and suggestions of a simpler customs union, which was based on the unqualified but largely unchallenged belief that wine was integral to the Community agricultural project. Further, what had significant bearing on the tone of the wine negotiations was a series of decisions taken many years earlier, while the Common Agricultural Policy's structure was being established. Earlier discussions from 1957 to 1962 on the Common Agricultural Policy eventually came to centre around ‘prevent[ing] farm incomes from falling more and more behind incomes in other sectors’ and addressing the ‘disequilibrium between production and consumption . . . problems which have become almost insoluble within the frontiers of a single state’.Footnote 70 Likewise, as Member of Belgian Parliament Maurice Van Hemelrijck from the Belgian Christian Social Party stated, in attempting to explain the principles underpinning discussions on the future European agricultural project,

The functioning and the development of the Common Market must, for agriculture, go hand in hand with a common agricultural policy. With such a common agricultural policy, we hope to increase the productivity of agriculture, ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural population, stabilise the markets, guarantee the food supply and ensure reasonable delivery prices to the consumer. The development of the common agricultural policy will take into account the special nature of agricultural production due to the social structure of agriculture.Footnote 71

The language used and ideas generated during this earlier time set into motion the increasing legitimacy of a discourse that was based on ensuring that farmers’ incomes did not fall further behind those in other sectors. The discourse included the need for the preservation of the family farm to be recognised as an essential component of any European agricultural order that was to be established, which was to be pursued through various measures like price support and balancing consumption and production. These early ideas pushed a social policy agenda onto the stage, and by the time serious discussions began on the creation of a common wine policy, the environment created by these prior discussions added pressure to the course of the wine negotiations, while also limiting their scope.Footnote 72 This, for instance, was why the technocratic ‘copy and paste’ offered by the Commission was unacceptable. It would not have addressed the social policy aspect as it related to the wine industry, for the industry operated in a more complicated fashion than the other sectors. This also explains the unique mechanisms within the Community market for wine. For example, the automatic pricing and intervention schemes, which were an essential and basic part of the milk and cereals markets, were not used in the wine market. Wine was far more subject to variations in both annual harvest sizes and in market fluctuations, which taken together made it a more volatile agricultural market than its comparable cousins.

Wine's Fit within the Common Agricultural Policy

The European Economic Community was aware that bringing Europe's vineyards under a common aegis would be testing. The EEC recognised from 1961 that because wine in Europe had been ‘organised on a national basis, in accordance with the specific situation of each country, [as a result] the viticultural economies of the Member States are significantly different from one another', but believed that ‘the creation of the single wine market . . . will be able to mitigate these difficulties’.Footnote 73 However, they did not anticipate how strenuous this task would be. The Common Wine Policy was difficult to negotiate because of three major reasons – first, wine was not a good fit with the rest of the products for which common markets were being created, second, agreed best practices for wines in Europe were lacking, making compromise difficult, and, third, tension existed between economic and political imperatives, which exposed broader uncertainties about the goals of the Common Agricultural Policy.

Wine's difference to the other agricultural products which were to have analogous markets to it is most obvious when looking at its most closely related agricultural markets, which were those for milk and cereal, the former of which suffered through the milk lake and butter mountain, akin to the wine lake of the late 1970s and 1980s. Even then, there were important differences. While milk and cereals are base agricultural products, wine is not; rather, it is a processed product. Grapes that were to be converted to wine could simply have remained with their grapes-for-eating brethren under the fruit and legumes market. In contrast, milk has a common market, but its derivatives cheese or butter do not.Footnote 74 One particularly compelling reason to believe that the wine industry was accorded a special kind of place in the pantheon of Europe's agricultural products because of its identity was that a market was created for it amongst these other base agricultural products and to the exclusion of one or several alcohol markets.

One commonality to most wine growing in Western Europe is the practice of monoculturalism, which made those in the wine growing profession vulnerable. A bad harvest would represent a devastating loss of revenue for those who had no other sources of income or had not diversified with other crops. This was acute in the region of Languedoc, where a large percentage of the region's economy was tied up with the wine industry. Most other farming sectors were hybrids, and those who had such operations were sometimes derogatorily termed ‘polyculturists’ by Midi vignerons. As M. Soulié, a vigneron in the south of France commented,

The viticulturalist, in monoculture, is more open, more evolved than the polyculturist. We, the viticulturists, we work to produce and we're in search of improving that production. The polyculturist who grows three or four crops, there's always some disappointment; he can't advance his research, his reflection, as we can advance ours, to always do better . . . produce better. Governmental projects want us to become polyculturists, because monoculture is quite dangerous in a system like ours where there's no guarantee, no minimum [income] to live, because in socialist countries the state intervenes. But here, when there's a bad harvest, it's explosive.Footnote 75

A frequent occurrence was that those who produced milk, even chiefly, would do so often in combination with something else, such as raising pigs or poultry (with the notable exception of dairying in mountainous regions, which tended to be small-scale monoculturalist pursuits yielding low income). These polyculturists also tended to join and be represented by general agricultural groups, like the powerful National Federation of Agricultural Holders’ Unions (Fédération Nationale des Syndicats d'Exploitants d'Agricoles; FNSEA), which the Midi vignerons decidedly eschewed. In fact, in spite of FNSEA's considerable status and growth during the 1960s and 1970s, ‘the wine growers [of the Languedoc] did not feel as if they belonged to this organisation and participated little in its initiatives’.Footnote 76

The different measures taken for the milk and cereals markets did not politicise them to the same degree as similar measures for the wine market. Part of the reason for this was that the introduction of quotas had a fairly immediate effect in the intended direction: the quotas halted what had been a continuous increase in milk deliveries but without effecting a dramatic decline, thereby averting a potential backlash from dairy farmers.Footnote 77 Moreover, the wine market was more exposed than the other agricultural markets (perhaps except for fruits, especially in the Mediterranean). Wine as a whole was more exposed to global processes and pricing than any other sector with a common agricultural market. Table wine and quality wine alike were more subject to international pressures and determinants impacting the end price of their product,Footnote 78 while the same was not true for milk, meats or cereals. The lack of consistency in pricing or of the stability of markets in wine, which was more readily achieved in those former markets, perpetuated the ‘feast and famine’Footnote 79 cycle of wine.

Another major reason why agreeing on a wine policy was so difficult was that there were no established best practices in wine. To observers from non-wine producing countries, such a statement would probably seem like common sense. But to those from countries with strong wine producing backgrounds, there was rightness or wrongness in wine growing traditions which meant that, without objective standards by which to measure these, compromise was difficult to reach, because compromise entailed ‘giving in’ to another country's ways of doing things. Another impediment to dealing with this issue more openly was the seeming inability of countries to simply say that there were different cultures of wine growing – in the technocratic environment of the European institutions of the time, the currency in Brussels was not in sentimental idealism or in explicitly raising identity issues in negotiations. Even in those negotiations that merited discussions on culture and tradition, in a post-war context of creating a new European order, they were not very welcome.

This was not an area where one could uncover an agreed-upon set of best practices. Wine in the member states was about tradition, heritage, organic processes of development and culture. A good example was the acceptance of the practice of chaptalisation, the process of adding sugar to unfermented grape mustFootnote 80 in order to increase the alcohol content after fermentation. There is no particular rightness or wrongness to this process, but the Italians disliked it and the French and Germans had permitted this in certain wines for many generations. Chaptalisation is used traditionally in cooler areas where white wine grapes are grown to improve the final taste and reduce acidity. This climate related tradition did not arise in Italy, for Italians did not encounter the issue for which it was a solution, whereas it was a useful way to improve taste in certain German and French regions. Likewise, different opinions about edulcoration, the addition of concentrated grape must to sweeten a wine which is otherwise finalised, were presented as technical facts by Italy and France during a CSA meeting in July 1969, with the resultant ‘solutions’ each party gave to the problems simply being references to what was done at home; a standstill was then hardly a surprise. The process of negotiating wine was essentially more akin to negotiating over value and dominance of cultural practices in a final European wine policy. The creation of the other markets, such as those for cereals, were, if still difficult, more straightforward, more technocratic and less imbued with symbolic value, identity and culture than the one for wine.

Economic vs. Political Imperatives in Negotiating Wine

The tension between economic and political imperatives facing the European Community institutions was a significant problem impeding progress during negotiations over the Common Wine Policy. The question ‘whither the CAP?’ loomed uncomfortably over the discussion, to which the answer in the early 1960s had been to prioritise political and welfarist imperatives over economic ones. Ann-Christina Knudsen's arguments about the moral economy of the Common Agricultural PolicyFootnote 81 are apt in this discussion: the value of maintaining parity in farmers’ incomes and of supporting the continuation of the family farm were part of the design of the fabric of the nascent CAP. By the time the CWP negotiations began, the direction of the overall agricultural project was set, and within its structure was a moral compass that harboured difficulties the wine policy negotiations exposed.

The difference between quality wine and table wine is crucial to understanding the course of the CWP in the policy's first decade. Much as beauty is in the eye of the beholder, wine desirability is in the subjective tastes of the drinker. Undoubtedly there is some truth to the idea that ascertaining the value and quality of wine – if otherwise free from faults like being corked – is inherently a subjective analysis. Some would go so far as to say that ‘the quality of any wine is socially and politically constructed’.Footnote 82 Certainly, in the process of even claiming there ought to be one category for wines considered to be high quality and one category of wine considered to be low quality – euphemistically ‘table wine’, and previously in France also known as ‘bulk wine’ (vin de consommation courante) – signalled a process of political construction.

This political construction was partly a response to changing social constructions of wine, where alongside the decline in wine consumed per capita in Mediterranean countriesFootnote 83 came ‘the development of a new wine drinking culture in France’ in the 1970s.Footnote 84 The change was propelled by the tastes of the growing middle classes, who drank less wine and furthermore did so, and also selectively chose their wines, to ‘[enable] them to differentiate themselves from other social groups by adopting the ways of drinking that were once the preserve of the haute bourgeoisie’.Footnote 85 Relatedly, this growing middle-class voter base was becoming less enamoured of the idea of tax dollars propping up ailing industries that produced goods which now seemed outmoded. The criteria that was used to develop the two different wine categories used a combination of alcohol percentageFootnote 86 and geographic localeFootnote 87 to designate a wine as being in a better category: even the nomenclature itself – assigning one category as ‘quality’ surely suggests the other is not, regardless of cosmetic euphemistic attempts to avoid this – was evidence of construction. Yet this political construction was also partly in response to another imperative: table wine and quality wine were operating as different economic goods in the market.

The CWP negotiations, already beset by disagreement on best practices in production and as well as wine's poor fit with the other agricultural products under the purview of a European policy, were hampered by the difficulty of dealing with wine as an economic good. Table wine and quality wine operated under different economic pressures, yet the two were subject to the same policy. Quality wine increasingly behaved as a luxury economic good, for which demand increases more than would be proportional as incomes increase; by contrast, table wine began to shift from being a normal good to being an inferior economic good, for which demand decreases as incomes increase.

The CWP did not reconcile this growing economic difference between table and quality wines. It would have made sense for there to be two sets of economic policies. From a political point of view, it would have been tremendously difficult, not to mention unpopular, to institute two policies for wine grape growers, whose products were ostensibly the same, even when the products were subject to different kinds of economic pressure in markets. A small effort made to differentiate the two was taken with the establishment of regulation 817/70, which complemented 816/70, the principal body of the CWP. While 816/70 was the focus of the Community's efforts to intervene in the European wine industry and is what is largely being referred to when discussing the CWP, the Commission created 817/70 to lay down additional provisions for quality wines. This regulation was largely a formal exercise, for 817/70 straightened some administrative lines in quality wine labelling and naming as in article 12,Footnote 88 which regulated the use of ‘quality wine produced in a specified region’, or VPQRD, but had little other impact on quality wine growers.

Overproduction of wine was a serious concern to many parties, but most especially to the French, whose insight was informed by their own saturated wine market – even despite aggressive and successful efforts to curb and then cut off their Algeria imports – and increasing farm support payments. Despite confusing and conflicting statistics suggesting it was permanent, temporary or even no longer an issue, the Council of Ministers had formally stated as early as 1961 that ‘permanent surpluses are the cause of serious difficulties in the wine economy’.Footnote 89 With lower quality wine, the route that would have made most economic sense was to forcibly cut down on wine production through methods like grubbing up vines or allowing those wines to bear the brunt of the market, which would have forced producers of these wines to find other employment. But, coupled with statistical and informational problems, the political problem of buttressing farmers’ incomes was given more weight. The policy went through, even though the mechanisms of this policy encouraged further production of wine, with the promise of Community support in the case of poor sales or overproduction through price fixing for income support and costly measures like distillation and storage. This was clear to the French throughout negotiations. Reviewing the agreement reached by the Six EC member states on the wine policy, François Seydoux, the French Ambassador to Germany, commented, ‘and is the European Community to drown in a sea of wine?’Footnote 90

Conclusion

One of the more complicated integration aspirations of the Common Agricultural Policy was its wine policy, which required the Six to face relinquishing sovereignty over their wine industries. During negotiations, the French government was well aware that the advantage of the Common Wine Policy was that it would be the Community, rather than the French Ministry of Finance as it stood at the time, that would ‘bear’ the ‘serious financial risks’Footnote 91 that taking on the care of the wine industry would entail. But the French government was nervous – at an inter-ministerial meeting on 17 January 1968, the SGCI relayed its analysis of the situation: ‘the construction of the Commission's text is based on the assumption of a deficit in wine production in the Community market. A closer analysis shows that this market is in fact in a position of equilibrium that would break, if no remedy is taken, to lead in the coming years to a situation of permanent surplus.’Footnote 92

The issue of the political and economic perspectives on wine was highlighted by the different stances taken by the French Ministry of Agriculture and the French Ministry of Finance: the former, well aware that it would be unpopular with farmers to have such a divide, did ‘not think it would be appropriate to separate, in the negotiations, regulations for quality wines and those for table wines’,Footnote 93 which the latter had also suggested, on the premise that this would be the sounder and more financially viable route. As the French Ministry of Finance representative argued, ‘our main commercial interest lies in the export of quality wines. Concessions made in the field of V.P.Q.R.D. wines would allow us to be of uncompromising rigor on table wines’.Footnote 94 The form of the CWP meant that VPQRD wines came under the purview of national decision makers and ‘restricted the scope of most EU regulation to table wines’.Footnote 95 One may well wonder what French farmers, especially those who produced table wines, thought of these negotiations. Their role in negotiations in Paris, much less Brussels, was largely limited. Caitríona Carter and Andy Smith, in arguing that the popular multi-level governance (MLG) model is too simplistic to explain the dynamics at play in European Union policy making, emphasise that in France for instance, the French national position is often defined by well-placed socio-professional actors.Footnote 96 This may be true now in contemporary accounts, but this was not the case in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Despite a historically fierce sense of independence, the legitimisation of the idea of regional monoculturalism in wine growing southern France, especially the region of Languedoc-Roussillon, led southern farmers to expect help from the Ministry of Agriculture during various crises (years of poor production or poor sales, depressed prices, foreign competition, among others). For all the region's desire for independence, French vignerons in general have since the mid-nineteenth century been heavily subject to the influence of national and international trade by virtue of being – and needing to be – well-integrated into the national market.Footnote 97 Those who had been successful at negotiating this – those in Bordeaux and Champagne, for example – were far removed from the kind of dilemma facing those in the Midi and had little interaction with the welfarist parts of the national government. The vignerons of the Midi were not very outward looking before the crises that faced France, Italy and the CWP in the 1970s. During the time of the negotiations, their emphasis, relative to other French vignerons, had been to engage with Paris only when there was a pressing regional need. Farmers were forced to change this way of acting when they faced the confluence of the reorganisation of the political overhead for their profession in the form of the EC and the CWP, abnormal harvests and the declining popularity of their product. Initially, as much notice as the French vignerons gave the new CWP was that it was supposed to mean an increase in exports via more open markets.Footnote 98 As a vigneron put it, ‘in the period preceding the Common Market, they told us, “you know, we must enter the Common Market because you will see the free exchange of your produce, you won't have any more problems sending a case of wine to Belgium, England, and Germany”’.Footnote 99 They were to be disappointed.Footnote 100

That the CWP was created at all, given divergent views on vine growing, wine production, labelling and unique traditions and customs in oenology, was a significant feat of national harmonisation and will. As mentioned previously, as late as in 1969 the FAO had remarked that the Community's common wine policy ‘has indeed made very little progress and the major problems remain still to be resolved’.Footnote 101 Yet less than a year later, the expansive and ambitious CWP emerged. The wine market – as the last to be finished – was negotiated under a kind of ‘pressure to complete’, because it was seen as necessary to include vignerons and wine in a common project which encompassed European notions of the image of the family farm, a sentiment and responsibility intimately familiar to French politicians and Eurocrats. But while the negotiation of wine's inclusion in the CAP was difficult, the course of its policy became more problematic yet through the next decade: a wine war erupted between France and Italy in 1975, the wine lake grew steadily from 1976 onwards and economic downturn continued through to the end of the decade, causing many vignerons in the southern France to lose or face nearly losing their livelihoods and as a result to blame in turn their representatives in Paris and Brussels and the CWP.

That the French were willing to accept the European Community's influence in la France profonde – rural, ‘true’ France – was noteworthy because it was so unprecedented in a country that had such strong control over its agriculture, stemming in part from French identity being tied to images of idyllic pays. This process was akin in some ways to the cooperatives saving the livelihoods of small-time vignerons in the first half of the twentieth century. In the 1980s the Languedoc-Roussillon vignerons began to adopt in earnest the policy of quality that policy makers and lobby groups had been concertedly pushing for throughout the previous decade. Along with a general turn in European Community agriculture to a policy of quality that included foods – which would become accompanied by a rise in the interest in identifying and protecting foods from certain regions, under the geographical indications regime – the Midi began to make serious and sometimes fruitful, even if slow, transformative efforts towards adopting the policy of quality to produce more ‘controlled designation of origin’ (appellation d'origine controllée) wines. In this regard, the eventual designation for local wine (vin de pays) very much benefitted the Languedocien producers.

Transforming an industry in a country where the said industry was unevenly distributed, and, in certain quarters, where constituents involved resisted change and distrusted policy makers, was a quagmire for the French government; indeed, ‘the question was: how does one transform a rural country with a large peasantry and where small, private businesses proliferate around a modern industrial state, without destroying the fabric of society?’Footnote 102 The response the French chose was to use the machinery of the European Community to deal with an ailing agricultural sector, much as Alan Milward asserts that France, along with other Western European countries, did with the whole of their agricultural welfare systems.Footnote 103 But the wine sector was distinct in a few important ways from the other markets such that it was not necessary for wine to have been included under the Common Agricultural Policy; further, the heavy influence of the French over the course of the wine policy negotiations meant they could have forced an exclusion for wine to be made. That they continued to seek the European Community, despite the political importance of wine in France and its place in the French cultural psyche, spoke volumes about their need to unburden themselves of the national wine sector. This was not without consequence – the later reaction from the Midi was angry and even violent to what vignerons from there saw as abdication of state responsibility. Though initially scattered, their movement in response to the changes in wine policy quickly became, by 1980, both more locally and regionally organised and outward looking, even if with mixed results as to effectiveness. This challenges the pervasive idea of the isolated and independent French rural farmer who could not reform or adapt to modern pressures.

The link between agriculture, identity and tight French control over key national industries considerably complicates the situation. Creating the Common Wine Policy breached some important French values of agricultural state control and national self-identification. The form of the initial Common Wine Policy was against the desires of the French national government, despite their very strong negotiating stance, suggesting that the state is not always able to retain its interests in pursuing policies at the level of the European Community. In essence, Milward provides an explanation of economic rationality, but not the motivation for ultimately pursuing such policies, especially for sensitive, culturally important segments of the economy. While this article may also add to theories of European integration that posit national economic interests were drivers of integration, it also complicates them. If, as authors like Andrew Moravscik argue, rational self-interest of nations led to intergovernmental bargaining based overwhelmingly on domestic economic terms, it does not seem to follow that the French government should choose to pursue a policy that was very likely going to cause eventual displeasure amongst the lobby groups of key domestic industries.Footnote 104 The French were motivated to save the ailing wine industry, and knew they were unlikely to be able to cope with the growing financial cost of it. But choosing the European Community as the vehicle for this was not a straightforward choice.

The French had considerable economic concerns about the creation of the CWP, for a policy which needed to operate under a broader economic requirement of the free flow of products meant less ability to control imports and exports. Maintaining control over the flow and taxation of imports and exports would have been useful to the French, given that Italian production was on the rise and, thereby, there was the risk of an inflow of Italian wines. France's viticultural traditions are also deeply ingrained and upsetting them meant politically risking the wrath of strong agricultural lobbies. Overall, it seemed in the French interest to retain control over their wine market. In this situation, a loose policy removing some custom tariffs, a quota system or even a more robust customs union seemed a better option, but the policy adopted was far more comprehensive and integrationist and would become further so throughout the following decade with new regulatory amendments and additions to the CWP.

That the European Community took on the project of integrating national wine markets indicates integration theories around intergovernmental bargaining and national economic self-interest are deficient in providing a full explanation for this case study. The negotiation, creation and evolution of the European Community's wine policy does not fit particularly well into either theory and is a case study of an economically minor, culturally significant sector of the Common Agricultural Policy that persisted despite major challenges not only in the 1970s but in the following decades. The French government voluntarily and strategically decreased its role in its domestic wine industry, by first devolving power upwards to the Community via the CWP, and then, after a wine crisis between the French and the Italians in 1975, also downwards to local and regional groups. In under a decade, a policy heavily tied up with French identity and seemingly carefully controlled by the French government was, by the end of the 1970s, largely the purview of the European Community's institutions.