In 1918, a group of international diplomats convened to redraw the map of central, eastern and southeastern Europe. This language of ‘redrawing the map’ is regularly recited in studies of the end of the First World War, a moment when more than a dozen new states were founded in lands that had belonged to the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, German and Ottoman empires.Footnote 1 But what did such an idea mean on the ground? In what ways would these invisible, often arbitrary political boundaries become realities in daily lives? Charted maps created in this period offer us some clues. These maps served a variety of functions: to inform wider audiences of new political boundaries, to reify these boundaries in popular imagination, and to challenge the ways borders were being imagined. Such maps are evidentiary traces not only of the territories and partitions that they aimed to represent, but also of the relationships among power, propaganda and infrastructure. Each map is a palimpsest with multiple layers of geospatial, infrastructural and diplomatic considerations.

The post-war moment was a time of political uncertainty, rapid change and high emotion. Frenzied border changes created a need for quick polemical output to claim contested territory, which tended to result in unresolved and unguarded articulations of the border. Such products can serve as historical artifacts that illuminate the politics and propaganda of place. This article analyses maps produced in Italy and the Yugoslav state during the early 1920s to investigate how a range of actors understood and sought to legitimate a contested border.Footnote 2 Using the tools of art history, it analyses maps as one might take on a twelfth-century bronze basin, using context as appropriate and available but placing the object itself at the fore and mining it for as much information as possible. This approach results in three differences from traditional historiographical strategies: first, because in this method maps are cast in a leading rather than supporting role, the undeniably rich layers of information in them is allowed to contribute directly to our historical understanding, neither relegated to a role of graphic supplement for an otherwise established narrative nor passed over in the archive because they turned up alone, unaccompanied by a folder of textual documents. Second, placing maps as centrepieces allows for an unencumbered and efficient comparative analysis of the maps themselves. Finally, this approach avoids a narrow focus on the actors made available by the archive; instead, it encourages an excavation of the traces of the many agents involved in the production and consumption of such maps, thus giving voice to otherwise invisible figures who played a role in making new political boundaries lived realities.

People living in the Italo-Yugoslav borderlands had their own mental maps of the spaces they occupied, imaginary conceptions cemented by cultural and familial bonds, historical legacies and myths, and infrastructural realities.Footnote 3 If competing states hoped to cultivate legitimacy for their right to control land – in the eyes of locals, as well as in the eyes of the international community – they needed to forge institutional and infrastructural networks that reinforced individual locations as belonging squarely in their national purview. For the political stakeholders, maps created visual affirmation of their legitimate claim to a certain piece of land, a vital complement to verbal justifications. In the contested lands at the heart of this study, one could stand atop a mountain or at the end of a footbridge and claim: ‘Here begins Italy!’ or ‘This is Yugoslavia!’ But such claims would fall flat unless the multiple and varied groups living in these regions, as well as the foreign statesmen who negotiate treaties, conceived of the political borders in similar, if not identical, ways. Thus, ‘redrawing the map’ of southeastern Europe was not a task left exclusively to diplomats and politicians but one undertaken by an array of architects, engineers, tourist bureaus, artists and cartographers, who set out to cultivate social, economic and infrastructural networks that would forge an imaginary geography that correlated with the political maps. Charted maps, I argue, both reveal existing mental maps and help to shape new ones.

In teasing out the relationship between cartographic representation and mental mapping, I explore four different perspectives on maps as drawn on paper and in the mind: as polemical depiction of social science data, as articulation of geographic coherence, as infrastructural experimentation, and as local effort to reimagine and reinforce newly decreed borders. While these four frames emerge out of the specific historical conditions considered in this study, my interest in them revolves around their potential to be applied to a variety of historical contexts, both near to and far from southeastern Europe in the 1920s.

The maps chosen for analysis here are representative examples of broader patterns, practices and tendencies that I have observed among several hundred examples that I found in archives and libraries in Rijeka (Fiume), Trieste, Pazin (Pisino), Zara (Zadar), Split and Belgrade, and also in digitised collections of journals, newspapers and foreign affairs documents.Footnote 4

The two states competing for these territories had vastly different political, economic, national, regional and professional circumstances, and maps created on both sides of the border were designed by a range of actors and aimed at diverse audiences. Accordingly, there is no chance of truly parallel assessment – there are no apples-to-apples comparisons here – and any attempt at equivalence would be artificial. Thus, this article does not attempt to perform a sequence of comparisons of one map produced by Italy with an equivalent map produced by Yugoslavia, although when juxtapositions and similarities present themselves they are readily engaged. Instead, this study takes the map, rather than the nation-state, as the primary object of study, and draws conclusions or observations, state-oriented or otherwise, from that starting point.

All these maps engage with similar deep-seated concerns about state coherence and vulnerable borders, but, by the interdisciplinary nature of this study, different disciplines will consider one map to have a greater resonance than others. For a scholar of international policy, the map by the influential scholar and cartographer Jovan Cvijić – a significant figure at the Paris Peace Conference – might seem the most important of the examples below. For historians of media or of fascism, the cover of a widely circulated interwar Italian magazine will speak volumes on popular perspectives. Historians might dismiss train routes drawn by engineers and published in a technical journal as simply illustrating the minutiae of a niche field, whereas a sociologist or anthropologist concerned with professions, institutions, or civic infrastructure would find the same maps to be teeming with socio-cultural subtext under cover of dry, scientific truths. Considering these diverse maps together, on their own terms and in juxtaposition with one another, allows for an exploration of how this border was collectively constructed in the overlapping imaginations of those invested in the territory.

The Implicit Authority of Social Science and Formal Maps

Among the many borderland regions to be hotly contested following the First World War were the Italo-Yugoslav borders on and near the Adriatic Sea. Much of the eastern coast of the Habsburg Adriatic was promised to Italy in 1915 to induce them into the First World War, but as post-war negotiations took shape, the focus on national self-determination – and the favoured position of those advocating for Yugoslav interests – undermined Italy's ambitions. In 1918, the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, staked claims to these and other lands that Italy coveted. The Paris Peace Conference failed to resolve the border, and following more than a year of posturing, uncertainty and the occupation of the northern Adriatic port city of Fiume by a rogue irredentist militia, in 1920 the two countries signed the Treaty of Rapallo.Footnote 5 This allotted to Italy a few contested Adriatic territories, notably the Istrian Peninsula and the city of Zara (Zadar), defined Fiume (Rijeka) as a free state and assigned the remainder of the eastern Adriatic to Yugoslavia. But this agreement did not assuage Italian irredentist ambitions, and Benito Mussolini used anger over the perceived territorial losses to garner Italian popular support, fuelling his rise to power in 1922. A year later he coercively renegotiated Italy's eastern border to include Fiume, ending its free-state status and shifting the Italo-Yugoslav border to the river that flanked the city's eastern edge.Footnote 6 This new border would remain stable – albeit fervently debated – until the Second World War.Footnote 7

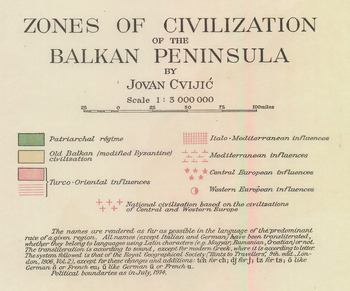

While border polemics did not dictate all border mapping, they nonetheless proved an important motive for mapping practices at this watershed moment. In one common polemical strategy, the implicit authority of a professionally produced map is paired with the authority of the social sciences and deployed as a tool in manipulating popular mental maps of the contested territories. We find this at play in the work of the well-known and internationally respected geographer and cartographer from Serbia, Jovan Cvijić, a champion of South Slavic unity and a member of the Yugoslav delegation to the Paris Peace Conferences. Aided by his scientific credentials and expertise, Cvijić regularly presented contested Adriatic territories as inherently Slavic and depicted Italians variously as interlopers, additions or courteously accommodated neighbours.Footnote 8 From 1918 to 1924, a period defined by the border in flux, Cvijić published in American journals maps and geographic studies that helped to legitimise Yugoslavia's claims to her current lands and that implied the need for border expansions. For example, in a highly detailed, lavishly printed matte fold-out map accompanying his 1918 article ‘The Zones of Civilization of the Balkan People’, Cvijić designated the contested borderland areas as part of the ‘patriarchal regime’ – used in the article to denote a generalised, modern Slavic category – while also including markers of ‘Italo-Mediterranean influences’ (see Figures 1 and 2). This linguistic framing of ‘regime’ versus ‘influences’ acknowledges the Italian presence while marking it as an additive component, layered atop a Slavic foundation. The dichotomy is further advanced with the map's graphic conventions, which denote regions of the ‘patriarchal regime’ using a solid green colour and signifying the ‘Italo-Mediterranean influences’ with a faint red hatch pattern layered on top of the solid green. Thus, Cvijić deploys the map's graphic conventions as a direct analogue to his verbal polemic: in both the linguistic framing and the cartographic markers, the Slavic component colours the territory while the Italian is added atop the essential colour, and by clear implication the character, of the land. Thus, in this ostensibly scientific analysis, Cvijić's cartographic strategies serve to draw a mental map that strongly favours South Slavic claims to the contested territories. These claims are fortified by their apparently honest and scientific acknowledgement of ethno-national multiplicity, mixing and blurred lines of influence.Footnote 9

Figure 1. Upper-left quadrant of 1918 Cvijić map, ‘Zones of Civilization of the Balkan Peninsula’.

Source: Included in Jovan Cvijić, ‘The Zones of Civilization of the Balkan Peninsula’, Geographical Review 5, 6 (1918): 470–82, foldout between 480 and 481.

Figure 2. Legend from 1918 Cvijić map, ‘Zones of Civilization of the Balkan Peninsula’.

Source: Included in Jovan Cvijić, ‘The Zones of Civilization of the Balkan Peninsula’, Geographical Review 5, 6 (1918), 470–82, foldout between 480 and 481.

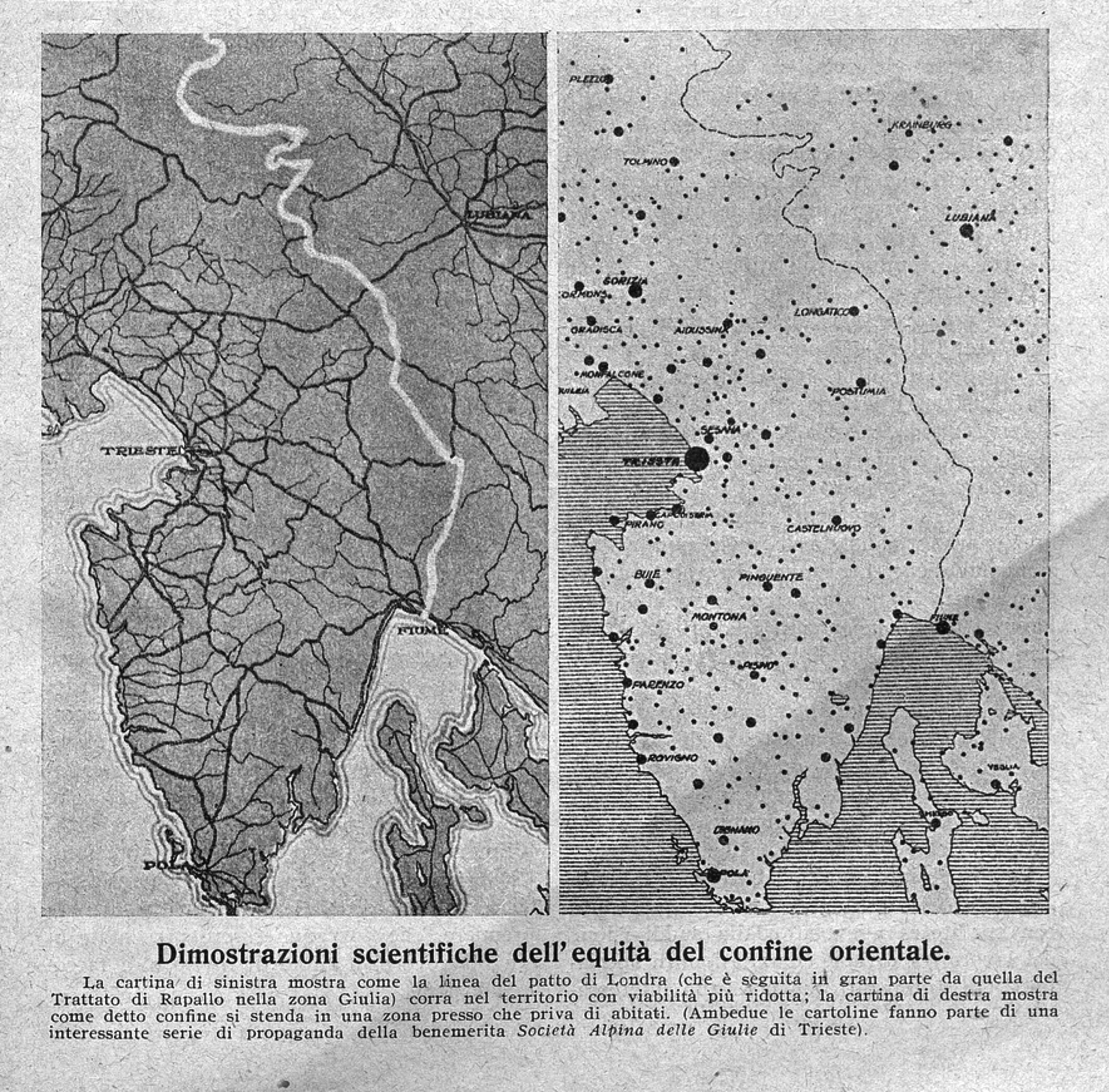

A similar exploitation of the authority of social science and the implicit certitude of formal, charted maps is on display in a pair of maps included in a popular Italian tourism magazine from 1921. The two maps are printed side by side on a single page that serves as a freestanding feature, unaligned with any other article in the issue (see Figure 3). Labelled, together, ‘Scientific Demonstration of the Equity of the Eastern Border’, the maps each present an identical expanse of territory in Istria, the contested peninsula at the northern tip of the Adriatic. Both show the line of the secret 1915 Treaty of London, which had promised Istria to Italy if they contributed to victory in the First World War; the line traces southward from the Julian Alps to terminate in the port city of Fiume. The image on the left shows transportation routes for both train and car, and the text explains that the borderline proposed by the Treaty of London ‘runs in territory with more reduced road networks’. The map on the right represents population centres using dots of varying sizes to represent the number of inhabitants in the surrounding area. The text explains, dubiously, that the proposed border ‘lies in an area that is free from inhabitants’. The manipulative possibilities of such maps are clear, especially the map of population density, whose graphic conventions the text misuses to almost comical extent. These sleights of hand buttress the overarching polemic of the maps and the accompanying text, which argue their case using demographics and the infrastructure of transportation networks to advocate an irredentist expansion of the border.Footnote 10 Ostensibly scientific evidence, with its presumed institutional vetting and constitutional objectivity, proves a convenient vehicle for the presentation and uncritical reception of polemical material. When such material is exhibited, as above, in the medium of professionally composed and printed maps, it gains yet another layer of implicit authority.

Figure 3. ‘Scientific Demonstration of the Equity of the Eastern Border’.

Source: Le Vie d'Italia, Feb. 1921, 163.

Images of a Coherent Italian Border

The historiographic construct at work in the preceding section, in which cartographic representations are understood to serve the goal of coaxing a population into the state's border interests, is complicated extraordinarily by the realities of the production of maps. First, states rarely prove monolithic regarding a desired popular understanding of the border. In addition to a state's own dissonances, the individuals and institutions creating the maps have multiple, conflicting interests and affiliations: to a company, a nation, a region, a town, a profession or an ideological movement. Furthermore, these mapmakers are, necessarily, tethered to their own conceptions of the place being mapped – their pre-existing cognitive maps – that are almost certain to differ from the mental maps sought by their employers or their state.Footnote 11 Such practicalities of map production complicate any image of singular influence. Certainly, in some of the cases considered in this article, states sought to control the cognitive maps of populations by managing cartographers’ production, and to some extent they succeeded in this supervision; however, such control was far from absolute. It was mitigated and side-tracked by cartographers’ individual agency, their imperfect skills and even their unconscious preconceptions.

Indicative of these complications are 1920s maps depicting the coherence of Italy. In 1922, Mussolini and his Fascist Party seized power. Their popular support drew heavily on nationalist grievances over ‘lost’ territories, and maps played an important role in staking claims to such places. The irredentist project regularly manifested in ostensibly innocuous representations of the domestic self that nonetheless made bold if implicit claims to the character and contours of Italian geography. One such example is found in an advertisement published in November 1924 in Le Vie d'Italia, the main publication of the Touring Club Italiano, a state-independent organisation serving Italy's emerging middle class since the late nineteenth century. From well before Mussolini's ascent to power, the magazine was committed both to fostering national(ist) awareness and to maintaining international ties. During the fascist period, it reached millions of Italians each year. As historian R.J.B. Bosworth has argued, the club had complex, shifting relationships with the fascist state, sometimes resisting it, sometimes acceding to its censure, and, most often, aligning with the regime on its own accord. Bosworth contends that the main purpose of the club's journals was to ‘spread the gospel of modern technology, modern business practice and modern leisure’ even as ‘a version of the nation was also insistently expressed’.Footnote 12

In the advertisement of interest, we find a three-quarter-page image promoting a manufacturer of knitwear (see Figure 4). Aside from four words, ‘HÉRION HYGENIC KNITWEAR VENICE’ (HÉRION MAGLIERIE IGENICHE VENEZIA) in bold white type, the ad consists of a map of Italy freckled with over 100 small red dots, each named by its location; these appear to stand for local suppliers to the company's factory, which is located in Venice and represented by a larger red dot outlined in white that is identified by the names of both the city and the company. Each supplier dot is connected to the Venice factory with a finely drawn dark line. Included, conspicuously because of its easternmost location, is the borderland city of Fiume, which had been annexed only months earlier after several years as a sovereign city-state. Italian territory is represented in green and enlivened by the dots, lines and text; non-Italian territory is represented in a featureless and opaque black, a stark graphic Other to both the lively Italian territory and the turquoise sea.

Figure 4. Le Vie d'Italia, Nov. 1924, cover.

The advertisement eloquently depicts an Italian national amalgamation through industrial activity. Its palate is the colours of the Italian flag – green, red and white – plus the comparatively nefarious black used exclusively to represent foreign territory. Coastal and terrestrial borders are represented identically, as detailed jagged lines not qualified by topographical features such as mountains or rivers; instead, they present as unmediated truths, facts that require no evidence to support them beyond the implicit authority of the cartographer and the printing press. Further binding together the national entity are the straight connecting lines that depict a centralised, single-level hierarchy in which hundreds of peripheral locations are beholden to a single central pole, the Hérion factory, which is indistinguishable from the city of Venice. The fine connecting lines also suggest the operation of a loom: not its product of threads already woven together but its initial feed to the loom's heddle reeds.Footnote 13 The imagery posits this textile-manufacturing company – notably located on the country's north-eastern frontier – as weaving together the raw material of the peninsula into an Italian national fabric.

In many senses this is an image of the ideals of the young fascist state: its centralised hierarchy, its ostracising of the other, its conflation of nation and corporation. Despite the resemblance, this advertisement and the cognitive map that it embodies speak more to existing and desired constructions of Italy within the Touring Club Italiano and the Hérion company than to any instrumental influence of the fascists. In 1924, neither organisation was explicitly beholden to the still nascent administration; their advertisement can be understood only to cater generally to the interests of the new fascist government, as much as any other institutional choice would be understood as influenced by widespread fascist paramilitary violence, including the well-known murder just a few months earlier of a prominent politician for his challenges to fascist practices.Footnote 14

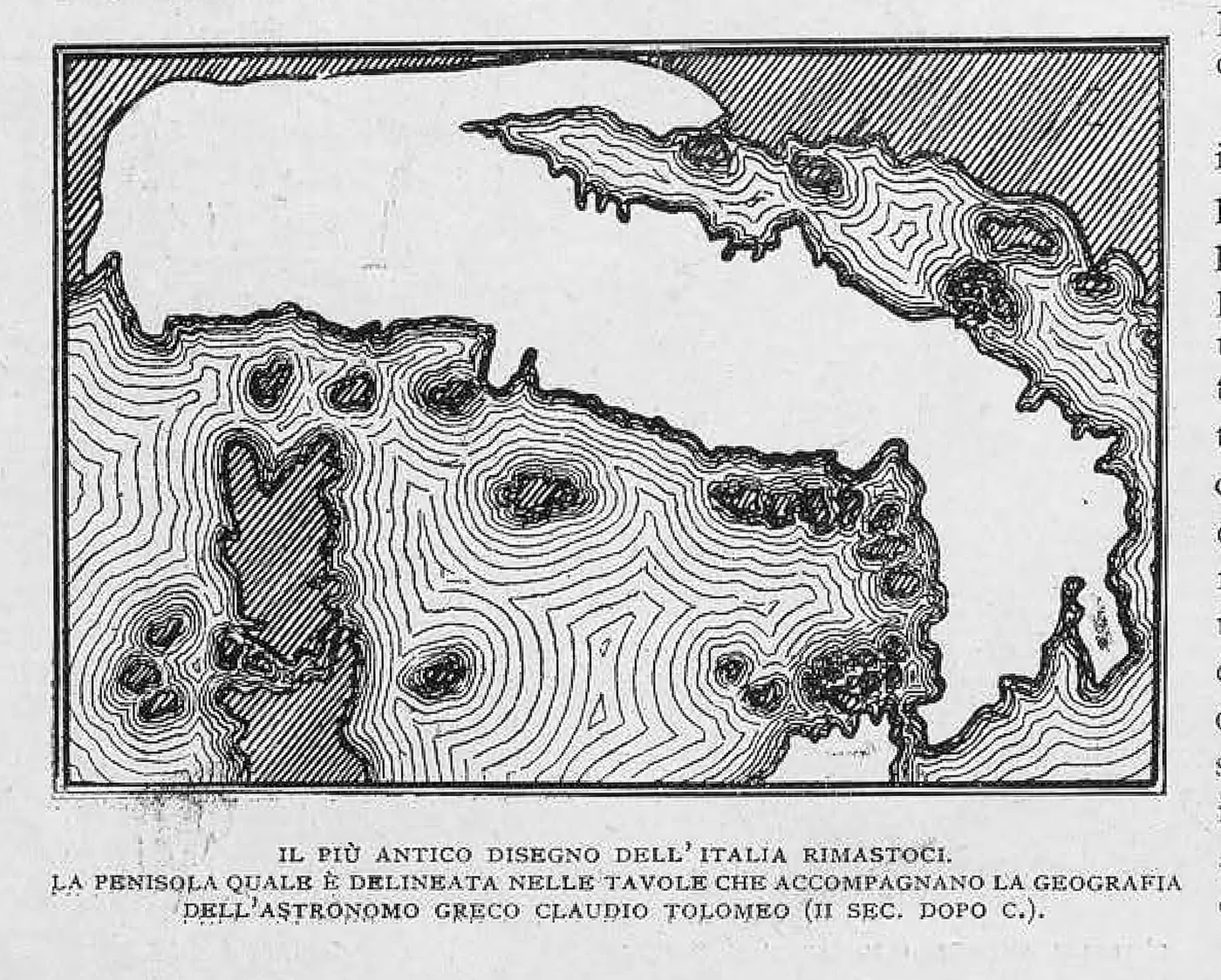

But even before the fascists took power, the Touring Club Italiano, long aligned with the cause of Italian national unity, boldly advanced perceptions of Italy's natural geographic coherence. An especially effective enactment of this polemic comes in the January 1921 issue, in an article that playfully muses on the cartographic shape of the Italian state. The eight-page article, titled simply ‘The Boot’, is constructed around a series of twelve maps of Italy plus three of other countries, all but one drawn with identical graphic conventions to incite comparison.Footnote 15 This standardised format depicts Italy using three main components: an all-white Italian mainland, outlying land shaded in a diagonal hatch and faux contour lines representing water. Much like the Hérion advertisement considered above, the conventions simply but effectively draw attention to the form of Italy, presenting it as a coherent, distinctly bordered, even natural entity. The lineage suggested by the supposedly historical sequence of Italian maps further naturalises the national form, projecting a cleanly bounded Italian nation eighteen centuries into the past.

The article opens with a familiar, twentieth-century representation of the Italian boot. This establishes the sequence's graphic conventions and offers an ideal model for comparison with the less familiar depictions of the peninsula, which are presented in rapid succession. In one particularly challenging exercise in boot-finding, a portion of Ibn al Idrisi's mappa mundi of 1154 shows the Italian boot in an extreme contortion (see Figure 5). The detailed coastal contours in the magazine's redrawing of the twelfth-century map give the appearance of a rigorously faithful reproduction, distracting from the duplicate's major anachronistic imposition, a dichotomous shading scheme that denotes Italy and not-Italy and in so doing represents Italian borders that were in no way implied in the original map. These ahistorical conventions are employed identically across the entire sequence of maps. The resulting graphic equivalence invites the reader to track cartographic variations from the second century to the twentieth, with a clearly denoted Italy as the benchmark.

Figure 5. Redrawing of the Apennine peninsula as included in al Idrisi's 1154CE mappa mundi.

Source: Olinto Marinelli, ‘Lo Stivale’, Le Vie d'Italia, Jan. 1921, 27.

The article offers multiple other playful maps that encourage a reframing of cartographic presumptions, but each asks the reader to find in these historical examples the now known and recognisable form of the unshaded, heavily outlined Italian state, thus reinforcing in the reader's mind the naturalised coherence and recognisability of the Italian boot. In every map that features a shoreline resembling the Istrian peninsula – and most do – the border line is drawn to include it. And in most of these maps the border clearly includes Fiume, at the time an independent city-state, visualising an irredentist goal that would not be realised for another three years. These include Ptolemy's map from the second century CE, in which the boot shape is immediately recognisable, albeit with a twisted ankle (see Figure 6). In this example the drafter reproducing the map clearly struggled with an awkward inclusion of something resembling the Istrian peninsula. A more convincing imitation of the shape of modern Italy is found in the reproduction of a map from 1650 by Piedmontese polymath Jacopo Gastaldi, in which the boot has the general form of contemporary projections, despite especially jagged coastal contours (see Figure 7). This map manages to more convincingly include Istria than the Ptolemaic example; however, the Alpine border reads as exceptionally arbitrary, represented in a wavy freehand gesture that quietly betrays the drafter's uneasy fabrication of the border, unable to find any features on the original map to conscript into the contemporary border line. This exception, a subtle draftsman's gaffe, only highlights the cartographer's efforts in this collection of maps to depict the bounds of Italy as incontrovertible. Indeed, the contrast between the absoluteness of the article's representations of the boot and the uncertainty of these geopolitical borders at this historical moment betrays the implicit polemical goal of the article: to solidify the border in readers’ minds not only by summoning the authority of a diversity of great minds – Ptolemy and al Idrisi not least among them – but also by fabricating an illusory, two-millennium-long popular consensus.

Figure 6. Redrawing of the Apennine peninsula as represented in Ptolemy's treatise Geography, from the second century CE.

Source: Olinto Marinelli, ‘Lo Stivale’, Le Vie d'Italia, Jan. 1921, 24.

Figure 7. Redrawing of the Apennine peninsula as drawn by Jacopo Gastaldi in 1560.

Source: Olinto Marinelli, ‘Lo Stivale’, Le Vie d'Italia, Jan. 1921, 29.

Reimagining Infrastructure and Localised Bordermaking

On the Yugoslav side of the contested northern Adriatic border, institutions and populations, having recently separated from Austria-Hungary, held mental maps that were largely rooted in past imperial realities (or, more particularly, in the realities of the Austrian or Hungarian sides of the empire, each of which had developed its own infrastructure). A revealing example of the post-First World War persistence of imperial and trans-national understandings of space can be found in a Slovenian-language tourist brochure published around 1921 by the town of Rogaška Slatina to publicise its main attraction: health spas.Footnote 16 On the interior of the rear cover of the tourist booklet is a central-European city-network diagram without any orienting topography or borders (see Figure 8). This schematic map seeks to chart travel networks – most likely train lines – among approximately thirty cities and towns, with the tourist town of Rogaška Slatina as the focus of this network. No indication of state borders or national affiliations is denoted. Instead, cities are set in a rough hierarchy according to their size or significance. For example, the locations of Sarajevo, Beograd (Belgrade), Zagreb, Budapest, Graz, Linz and Salzburg are marked by a circle within a circle; the relatively smaller hubs of Szegedin, Trst, Reka and Celovec (Szeged, Trieste, Rijeka, Klagenfurt) receive a single diminutive circle; the urban centres of Wien (Vienna) and Brno alone receive three concentric circles. A second, independent layer of urban significance, whose precise meaning is not clarified, is also present. It is denoted with an underscore on the names of important cities, including Prague, Budapest, Vienna, Belgrade, Brno, Zagreb and Ljubljana. Connecting all the cities are lines that are abstracted but not always direct. Some lines include demonstrative zigzags that appear to denote a convoluted or indirect route. Thus, the map included by and for this city's tourist industry makes a point of delineating transportation networks and the significance of other regional cities, as well as the ease or complexity of travel routes. Among all this signification, the map excludes any indication of national political boundaries, offering instead a conception of international transportation networks unimpeded by states. The map also, conspicuously, avoids references to the Yugoslav state, which more than a year earlier had acquired sovereignty over Rogaška Slatina and had taken control of the tourist agency that produced the map.

Figure 8. Diagrammatic map from interior back cover of Rogaška Slatina tourism book, very early interwar.

Source: Arhiv Narodne Biblioteke Srbije, collection: national material, uncatalogued.

Embedded traces of the map's creation process indicate that it was produced impromptu by a minimally professionalised designer. The map is hand-drawn and lettered, with consistent line weights and some controlled geometry that indicate professional tools and some drafting experience, but these consistencies are paired with unevenly slanted hand lettering, awkwardly placed city names and a glut of subtle drafting errors, most notably the repeated misalignment of connecting lines with city-circles. Taken together, the components indicate an ad hoc project that received little planning and no second drafts. But more incisively, taken as found artifacts, these otherwise easily disregarded traces of the production process enable speculative insights into the conditions of its production.Footnote 17 Vetting and oversight were minimal. The producers were likely bureaucratic operators rather than managers.Footnote 18 The primary creator(s) were not trained as mapmakers, and the map itself was a second thought in the pamphlet's production. As a result, the map can be read as the product of an unvetted local actor, whose cartographic presumptions stemmed from his or her own local knowledge, and not from a state mandate, professional standards or a regionally systematised process. The design task would seem to be the following: ‘Orient the viewer by conveying the location of Rogaška Slatina as well as the route there from surrounding relevant cities’. The designer's answers to this call, likely implicit in his or her own mental map, are legible in the final product. These include: Is topography essential, or at least worth the effort? No. Are state borders useful or relevant? No. Must I indicate the national affiliation of each or any city? No. Are the size and significance of the city relevant? Yes. Must transport connections among cities be shown? Yes. Should the difficulty of the route be communicated? Yes, but only schematically. Should state capitals be denoted? Yes, but not explicitly. The traces of the map's design process reveal a mental map mostly devoid of the trappings of the nation-state.

A close reading of this map paints a picture of an amateur cartographer composing for a bourgeois audience of potential spa visitors. The cartographer articulates a cognitive map in which state borders and topography need not be noted. Instead, a region is presumed to be best represented in terms of the cities’ relative sizes and the ease of transit among them. This is strikingly close to an imperial model.Footnote 19

Negotiations with new borders did not occur only in an abstracted touristic imaginary. To the contrary, the region's mental mapping was in a constant dialectical exchange with the evolving physical realities of the region's geography, bureaucracy and infrastructure, material realities that could themselves only be altered as corresponding mental maps were renewed and revised. The young Yugoslav state was continually interrupted by the borders that had been thrust upon it, and those interruptions would only be resolved as professionals imagined and reconfigured the territory in new ways.

Particularly challenging for professionals mapping and planning the borderlands of the upper Adriatic was that these territories were quasi-arbitrary fragments of the larger functioning machine of Austria-Hungary. The infrastructure of the new Yugoslav state was an uneasy amalgam, assembled from the remnants of multiple pre-war states. And while the Yugoslav national project boasted an intellectual pedigree comparable to that of Italy, the young state was also fragile, dogged by political uncertainty and ongoing conflict, and still reeling from wartime devastation and the resultant economic despair.Footnote 20 Train lines that traversed Croatia and Slovenia often ended in formerly imperial cities that were now held by Austria or Italy. Planners faced similar issues with roadways and telephone lines farther down the Adriatic coast, and even with ferry lines connecting islands. Rather than advancing a tourism industry or experimenting with coherent state-level imagery, as we have seen in Italian production, cartographic experiments in the Yugoslav state reveal the daily work of resolving this problem of old infrastructure overlaid by new borders. When new, evolving and contested borders sliced up the existing, proven imperial infrastructures, these professionals in engineering, architecture, planning and security recognised the pending lapses and rushed to remap the territory in order to begin to resolve its newfound complications. Through an analysis of this remapping, we see how they dealt unceasingly with a fundamental question facing interwar central Europe: How does one forge new institutional networks to cement borders and build a functional state when operating within a landscape that is so deeply dependent on remnant imperial networks?

The pages of Technical Bulletin: Journal of the Yugoslav Association of Engineers and Architects illuminate these challenges and also indicate a professional obsession with the design and construction of nationally-oriented infrastructure.Footnote 21 In the early 1920s, hardly a monthly issue was published that does not include a map-heavy article on railroad lines, telecommunications cable systems, or national highways, all revealing a prominent awareness of the border and its significance.

In these issues, the technical maps and their accompanying text present an understanding of the territory that is fine-grained, multi-layered and centred on the significance of the border. Often there is no evidence of a polemical agenda beyond building an understanding of those border conditions through the presentation of detailed factual and analytical studies. In other words, although the explicit task was to propose infrastructural solutions to conundrums that arose from border shifts, the implicit assignment was to imagine and represent novel mental maps for this unprecedented overlay of politics, territory and infrastructure.

For example, in April 1922, following a turbulent month in Fiume that included an independent fascist coup followed by an Italian military invasion, the front page of Technical Bulletin featured the troubled border and its effect on railroad planning. The article opens with this loaded assertion: ‘Since it is known that the Wilson line will not be our border with Italy, at this moment the question arises of how to connect Slovenia with the Adriatic Sea’.Footnote 22 With striking concision, these engineers articulate the entwinement of politics and civil engineering: a neighbouring country had undermined a treaty with military action, which resulted in domestic infrastructural problems. The existing train route from Ljubljana, the Slovenian capital and transportation hub, to the Adriatic port of Fiume passed through territory that was, according to the post-war treaties, to be shared between Italy and the Yugoslav state. However, the Italian irredentists restricted their neighbour's access. The article buries itself in the technical details of analysing the advantages and disadvantages of possible new railroad routes – directness, traffic, elevation changes, etc. During the Austro-Hungarian period, Ljubljana had been built up as a regional industrial hub dependent on its easy access to a seaport, taking advantage of a navigable low-lying route to Fiume.Footnote 23 Even though, with the border-shift, the foundational logic of this connection was suddenly gone, centuries-worth of industrial, bureaucratic and economic investment in the Ljubljana-Fiume connection remained. For the sake of regional coherence and trade, the Yugoslav engineers needed to relink the two cities.Footnote 24 But any new routes would require the laborious construction of inefficient rail lines through the new state's mountainous terrain.

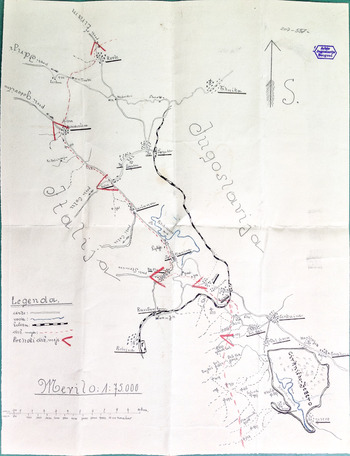

While the prose of the article dissects technical problems from various angles, a schematic, topography-free map that accompanies the article makes a more forceful argument: the Italians’ antics left the Yugoslav infrastructure inefficient, and Yugoslavs had no choice but to respond with sober planning and bold investment. The map spans from Rijeka on the Adriatic in the south to Ljubljana in the north, with a mesh of multiple train lines representing various, mostly roundabout connections between the two cities (see Figure 9). One of these lines, the most direct by far, bends slightly to the west and connects the two cities in a fairly straight path. However, a stylised broken line that denotes the new Italo-Yugoslav border cuts through this route and leaves nearly half of it in Italian territory. In contrast to this, to the east a tangle of lines denoting alternate routes connects the two cities in various roundabout ways, with a mix of details signifying the comparative difficulty of any alternate path. Among these, the line coming out of Ljubljana to the southeast is drawn with a coarse freehand squiggle conveying its inefficiency. Continuing southeast, the train line winds, splitting into multiple possible paths before making its way back west to the city of ‘Reka’ (i.e. Rijeka/Fiume). At one point the path includes a full loop, which may denote the route of an actual, onerous mountain ascent, or may simply be a freehand gesture used to emphasise the route's arduousness. This casual but expertly informed sketch of border-region train lines served to advocate a newly national understanding of the territory in which, despite its material insubstantiality, the border would define the territory and the physical realities that would soon be laboriously, and inefficiently, realised in the region.

Figure 9. Map showing new Italo-Yugoslav border and possible alternate train routes between Ljubljana and Reka (i.e. Rijeka/Fiume).

Source: Tehnički List, Apr. 1922.

Over the course of the mid-1920s architects and engineers found themselves caught up in the shifting border possessions and confronting, in their own ways, the consequences for the Yugoslav border of the rise of Mussolini's fascist Italy. They regularly published technical responses to the progressive loss of Fiume and surrounding territory, illustrating the cognitive map with which the profession made sense of the Adriatic and, in a way, of the Yugoslav state itself.Footnote 25

Local bureaucrats similarly struggled to resolve the complications that arose when locations with integrated Habsburg infrastructure were partitioned between the two states. The city of Zara/Zadar, midway down the Dalmatian coast, was transferred to Italian control in the November 1920 Treaty of Rapallo after a brief and uncertain period of Yugoslav rule. The city, like many contested locations, had a mix of Slavic and Italian speakers. Although a group of Slavic speakers had passed a resolution in 1917 declaring their intention to unite the city to a South Slavic country, Italy was not prepared to let it go.Footnote 26 The Italian Navy menacingly roamed the shores of the eastern Adriatic, and the renegade leader occupying Fiume, Gabriele D'Annunzio, threatened an equivalent occupation of Zara.Footnote 27 Thus in 1920, the Belgrade government agreed to hand the city over to Italy, even though it was not connected by land to any other Italian possession. Most other Dalmatian terrain was acknowledged in the agreement as undisputed Yugoslav territory.Footnote 28 This new urban exclave created a legion of logistical complications. For Italy, Zara's security and well-being would require regular shipments and a strong naval presence. For the Yugoslav state, the extraction of a central regional node from its domestic coastal networks required infrastructural ingenuity.

In 1921 the ministry of foreign affairs in Belgrade compiled an extensive report on how to deal with Italian control of Zara, which they called Zadar (the term I will use for the remainder of this section, as it focuses on Yugoslav reports and infrastructural challenges). Amid the scores of pages of analysis, which spanned from archival transfers to maritime sovereignty, there arises an ostensibly minor consideration over the management of telephone lines that were at the moment routed through Zadar.Footnote 29 ‘All land telegraph and telephone wires that have gone to Zadar have to be truncated’, the section explains. It continues, ‘Given the new demarcation of the Zadar territory, it is necessary and of particular importance that a telegraph-telephone station . . . should be provided in our territory near Zadar so there will be uninterrupted traffic with Split’. The report advises that this new station might be created by expropriating the home of a local Slavic resident, Peter Dušić, which happened to be located adjacent to the new border with Zadar. The house could also be used ‘for the official traffic of our border guards, clandestine and financial stations, and our organs located in the city of Zadar’, and ‘to serve as military and other border stations’. Thus, they imagined this not as a modest telephone operator's station, but as an all-purpose clearing house for border-region communications and even international intrigue.

At work in this report are not simply the logistics of shifting administrative offices, but the reconfiguration, and reconceptualisation, of territory. The new Yugoslav government was in the process of appropriating the remnants of an integrated network of Austro-Hungarian infrastructure – both material and administrative – that had included Zadar as an important node in its operational web. The partitioning off of this economic, commercial and transportation hub forced these mid-level administrators to improvise infrastructural solutions. The Yugoslav bureaucracy largely recreated itself from the Austro-Hungarian machine that had administered the region previously. But newly-drawn borders – particularly the Italian acquisitions of Zadar and Istria – disrupted the existing imperial networks, and Yugoslav engineers, planners and other technical and policy specialists were forced to reimagine the existing networks.

Some of the complications of this node-removal are made visible in a carefully drawn freehand map included in the report (see Figure 10).Footnote 30 The map shows the north Dalmatian coastline and adjacent islands, centred approximately on Zadar. It represents about a dozen winding telecommunications lines, each identified by a single three or four-digit number, and each of which connected Zadar directly to other cities. The map clarifies that Zadar had also been a hub of the regional telecommunications network, connecting Yugoslav towns on both the mainland and the islands that did not have direct lines between one another. The shift of Zadar's sovereignty to Italy meant that its role as a hub for Yugoslav communication lines would be no longer tenable, and the map describes an intervention: to reroute all the Zadar-traversing cables through a nearby town, Biograd na Moru, via the new switching station in Peter Dušić's former home. This would require the installation of new cable segments, drawn in red. The scheme would circumvent Zadar, moving the cables that ran in and through the nearby Yugoslav islands from their previous termination in Zadar to the new borderland operator's station.

Figure 10. The rerouting of Zadar Telephone lines, 1921.

Source: AJ, fond 334, box 12, unit 33, ‘Report in relation to Zadar and surroundings, 1921’, table C.

The map is an attempt to make visible an otherwise invisible network. However, the representation could not be entirely abstracted, since the essence of the problem was the physical location of those phone lines: electrical impulses that travelled through cables and connectors located in Italian territory needed to be provided with new cables and connectors in Yugoslav territory. The difficulty that these analysts had in imagining and representing their dilemma is legible in the map, which resembles an awkward combination of coastal cartography and electrical diagram. The report references the map as a straightforward illustration of the analyst's recommendation. However, under scrutiny and read alongside the report, we discover it to be a halting graphic negotiation of the problem's complexity. In conveying the richness and intricacy of the territory around Zadar, the map reveals both the visible and the invisible of both the present and the near future.Footnote 31 It offers a cognitive map that stemmed from past planning, borders, and demographics, but was entirely original. This ad hoc map, paired with a three-page report, not only struggles to represent what needs to happen to legitimise this border, but also implicitly asks why. And it is a big why, implicating national defence and Yugoslav foreign policy, espionage and border control, national business networks and maritime infrastructure.

Tracing the border 300 kilometres north, less than a month later the State Border Commission in the Slovenian town of Rakek produced a pair of maps depicting the local territory (see Figures 11 and 12). The town had become a collection point for Slovenian timber when a railway line from Ljubljana to Trieste was opened in 1857.Footnote 32 After the First World War, it had initially been allotted to Italy, who invested heavily in its railroad infrastructure. But, in an inversion of the case of Zadar, Rakek was reassigned to the Yugoslav State, under the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo, which specifically addressed its status as a border-town.Footnote 33 Like the Zadar map, the border commissioner's maps were also hand-drawn by a state official, also intended for consumption by the state's upper-level administration, and similarly rich with local detail about the contested border. But unlike the complex instructions embedded in the preceding map of Zadar, these maps have, on their surface, hardly any distinct prescriptions or agenda. Instead, their primary purpose seems to have been to convey to bureaucrats in the distant capital of Belgrade just how complicated the borderland was (and in the process, to gently illustrate how oblivious upper-level authorities were to the intricate challenges of the region).

Figure 11. Smaller-scale map included with a 1921 letter from the border commissioner in Rakek.

Source: AJ, fond 14 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Yugoslavia), box 207, folder 749; letter dated 24 Mar. 1921, State Border Commissioner, Rakek, to the Ministry of the Interior, Dept. of Public Security, Belgrade.

Figure 12. Larger-scale map included in a 1921 letter from the border commissioner in Rakek.

Source: Arhiv Jugoslavija (AJ), fond 14 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kingdom of Yugoslavia), box 207, folder 749; letter dated 24 Mar. 1921, State Border Commissioner, Rakek, to the Ministry of the Interior, Dept. of Public Security, Belgrade.

Drawn in the same hand, the maps represent, at two different scales, the region of the frontier under the purview of this commissioner. They are accompanied by a brief, handwritten report sent to the state's Department of Public Security, part of the Ministry of the Interior, which responds to a set of now-unknown questions about local administrative structure. The report also voices one major complaint: because of the low pay and consequent inadequate staffing, the border commissioner's various officers were unable to properly fulfil their duties with respect to guarding the border and monitoring trains that passed between Italy and Yugoslavia.Footnote 34 Under the cover of geography's supposedly unbiased rigour, the accompanying maps upstage the commissioner's meek written protests by depicting an unwieldy frontier with only the superficial trappings of state-sovereignty. Both maps show a border stretching from northwest to southeast, with ‘Jugoslavija’ (Yugoslavia) on the right and ‘Italija’ (Italy) on the left, in the largest lettering of each map. Taken together, the two drawings describe an intricately interwoven network of natural and manmade features, including roads, a train line, dozens of towns and villages, footpaths, rivers, a marshy lake and mountainous terrain methodically annotated with scores of elevation values. These features read as profoundly indifferent to the border, and they assemble to paint a mental image of the region as a geographically and infrastructurally coherent frontier in which the border that this commissioner is charged to enforce is hardly more than an imaginary line, signifying a distant and effete idea, drawn over and across more meaningful markers of human habitation and natural divisions.

The intricacy of the maps goes far beyond any instrumental illustration of border stations, or clarification of the domain that this particular office monitored. Instead it presents as a bare attempt to convey a mental map, to somehow communicate to the officials in Belgrade the complexity and the intricacy of the on-the-ground realities of this mountainous border. Two years earlier, the territory had belonged entirely to Austria-Hungary, with infrastructural networks developed to operate as a single, coherent unit; the new Italo-Yugoslav border must have seemed to this border agent the most artificial of impositions. These meticulously hand-drawn maps, drafted in an expert, authoritative hand, seem imbued with a pragmatic expertise that understands the territory and the vicissitudes of these wholly new considerations born of the awkward splitting of this domain. It is an almost desperate effort to convey a cognitive map of the region's complexity to a state administration that is in over its head. One can easily imagine the drafter admonishing an empty room late at night as he methodically draws the map, ‘If only they could understand this place in the way that I do . . .’.

This borderland map may well have been on the drafting table at the same moment in 1921 as the map analysed above that charts urban connections to the Slovenian spa town of Rogaška Slatina (see Figure 8). The two maps overlap in the territory that they represent, and they each illustrate the persistent challenges of redrawing the cognitive map of imperial borderlands to represent new state borders. The author of the tourism map did not include Rakek, or the border, or any other element featured in the commissioner's detailed visualisation of the new European (b)order. And this is understandable, since the tourist agents in Rogaška Slatina had a clear interest in maintaining and expanding their international clientele, a goal doubtlessly advanced by disregarding the borders that might interfere with the imperial networks on which their businesses had been built. In stark contrast, the maps from Rakek were drawn by the very figures charged with slowing those clients down. Indeed, at that early moment for the newly created border, those police, and the maps that they drew, may have been the most tangible realisations of the new border. But in a sense the two maps tell the same story, of the absurdity of imagining a border when nearly every network, whether tangible or immaterial, transgresses that invented line.

Conclusion

This article has focused on representations of an unstable border at a moment of peak uncertainty in order to uncover ambiguities, experiments and usually invisible dynamics. Maps of tourist routes, railways, supply chains, demographics, geographic forms and telephone and telegraph lines reveal how, on both sides of a contested border, cartography was utilised to change the way people conceived of political geography. The instrumental use of mapping was limited by the ability and will of cartographers and the institutions that sponsored them to imagine the territory in unprecedented ways. I have inched toward an understanding of these interrelated dynamics by organising cartographic examples under four different rubrics: maps that make polemical use of the implicit authority of the social sciences and formal graphic representation; maps that present a coherent image of a state in order to reify and naturalise its borders; maps that serve to explore the infrastructure of the region; and maps that examine local conditions and the contradictions and inconsistencies of newly imposed borders.

Taken together, comparatively, these maps offer an uncommon view of the dynamics of the disputed Italo-Yugoslav border, in which the real contest is not a matter of pushing a line east or west by 50 feet or 50 kilometres, as if it were a trench in the Great War. Instead, these maps reveal a battle to dominate understandings of place, to provoke new imaginings of vaguely familiar territories in a population that was watching the recreation of borderlines at astonishing speed. The global process of remapping political boundaries in the decade after the First World War entailed a thorough and surgical practice, which was prominently on display in southeastern Europe. These maps expose a reciprocal interchange between mental maps and charted maps, between the dreamed and the drawn.Footnote 35