Dutch activists attempted to initiate a Europe-wide ‘cane sugar campaign’ starting in autumn 1968. This campaign was one of the earliest instances of an initiative promoting global fair trade in Europe. Its stated goal was to render visible the ‘structure of world trade disadvantageous to developing countries’ through the use of sugar as a telling example.Footnote 1 As they announced their campaign to citizens across Western Europe, many acknowledged its objectives and actions. With European economic policies as a common target the pioneers of the cane sugar campaign successfully forged a Europe-wide network of like-minded groups. By 1971, however, it was clear that Europe was dividing them as much as it united them. National perspectives on the European project diverged and activists struggled to find ways in which to impact European politics. ‘The illusion that the European Economic Community contributes anything to unifying Europe, let alone the world, is already very old and very worn down’, an anonymous activist observed in 1971.Footnote 2

The history of the cane sugar campaign from 1968 to 1974 charts the way in which European economic and political integration provided activists with a common perspective, which led them to establish a European network and corresponding campaigns. Its demise sheds new light on a trajectory which came to the fore during the second half of the 1960s and can also be observed among other so-called ‘new social movements’. Fair trade activists moved away from an optimistic outlook on global and European politics as a focal point for swift and drastic transformation – a view of ‘grand politics’ – towards a more incremental view of change, which focused on local activism first and foremost. The failed attempts at transnational political transformation through global and European politics direct attention to the ways in which the local, national, European and global have not been mutually exclusive, but rather interwoven, frames of reference.

Europe has not figured prominently in the histories of social activism in the 1960s and 1970s. Just like the historiography on other social movements, accounts of the history of fair trade have emphasised local and national manifestations. As a result of the increased attention to transnational history, the global dimension has also received considerable attention recently.Footnote 3 However, European integration had rendered Europe a relevant frame of reference for civil society actors by the 1960s. This relevance is clearly visible in the history of trade unions, in which European cooperation became an important dimension.Footnote 4 Scholarship on the history of the consumer movement has also illustrated the importance of Europe for relatively new forms of social action.Footnote 5 Dougals Imig and Sidney Tarrow have formulated the expectation that European integration will redirect the expectations and actions of social movements towards the European level of governance.Footnote 6 The early history of fair trade history highlights that ‘Europe’ indeed mattered to European citizens during the 1960s and 1970s. Europe served as a carrier of hope of sweeping transnational transformations, a political target for joint campaigns and a relevant space in which to establish a network.

Analysing how Europe provided a space for social action during the 1960s and 1970s, this history highlights the social dimension of the process of European integration. In this respect, European integration has not been a linear development towards an ever closer union. In the following, I will discuss the entanglement of global and European perspectives at the start of the cane sugar campaign in the Netherlands in 1968, which catalysed attempts to coordinate a European campaign. Subsequently, the limited extent to which Europe could unite activists and how the difficulties in impacting European politics caused a disenchantment with Europe comes into view. This becomes particularly apparent around the eventual failure of the cane sugar campaign around 1974. The Europe-wide network of like-minded groups, however, survived the demise of ‘grand politics’. It continued to connect fair trade activists even as they prioritised incremental and local change, enabling a continuous exchange of ideas and repertoires and preparing the ground for the establishment of transnational organisations in the field of fair trade during the 1980s and 1990s.

Regarding the trajectories of global solidarity since the 1960s, this transnational campaign points out a crucial learning effect among activists during the early 1970s. Civic activism turned away from campaigns aimed directly at European and global political regulation during the 1970s.Footnote 7 However, it did not turn away from larger political questions altogether. Instead, activists turned to foregrounding specific issues and achieving change incrementally. They targeted individual companies, boycotted specific products and selectively supported countries in the global South. By attempting to change the world one step at a time, they kept their hopes of achieving a large-scale transformation in the long run alive.

Global Trade: A European Matter

Hopes for a post-colonial world in which the global South would not just be politically, but also economically autonomous, knit global to European politics together during the 1960s. The impulse to strive for a reform of the structure of global economic structures came from what was by the 1960s being called the ‘Third World’. Taking up traditions of anti-colonial struggle and pan-Africanism, the leaders of countries from Asia, Africa and Latin America discussed their position in a world order now dominated by the Cold War.Footnote 8 Instead of a divide between the East and the West, these countries proposed to view global relations in terms of a divide between the North and the South.Footnote 9 Assuming their economic dependence on industrialised nations to be one of the crucial factors hindering their own development, these countries channelled their joint political weight into international politics. As a result of decolonisation in the 1950s and 1960s, the number of states willing to associate with this movement increased rapidly. During the 1960s they could muster a majority of votes at the United Nations.Footnote 10 Aided by this majority, they adopted a UN-resolution to set up the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) for 1964, insisting in a second resolution that this conference should take steps in the direction of self-sustaining growth for developing countries.Footnote 11

Neither the 1964 and 1968 UNCTAD conferences, nor the more limited attempts to negotiate about single commodities, brought about manifest improvement for developing countries. National interests as well as regional agreements hampered the negotiations.Footnote 12 In particular, the Common Agricultural Policy, which was a cornerstone of the European Economic Community (EEC), contributed to the stalling of the UNCTAD negotiations during the spring of 1968. It encouraged the production of sugar within the EEC and fixed its price. It thus inserted an additional level of negotiation, binding the European participants at the UNCTAD conferences and regulating the relations of EEC-countries with former colonies of these countries separately from the relations to other sugar producing countries.

The failure to achieve change at these international conferences led European observers to conclude that change would have to start elsewhere. Encouraged by conversations with delegates from the global South, correspondents engaged in issues of global development pointed out Europe's crucial role. In this vein, Dutch journalist Dick Scherpenzeel anticipated that European politicians could become more forthcoming if the general public in their own countries would be aware of the issues.Footnote 13 ‘The political unwillingness of the rich countries has been exposed’, the activist Piet Reckman concluded after the disappointing results of the second UNCTAD conference in 1968. ‘Isolated actions to achieve a little increase in the budget for development aid are no longer meaningful’, the representative of the ecumenical group Sjaloom continued. In previous years the group had initiated several campaigns to promote global equality, and the course of the UNCTAD conference reinforced this commitment. ‘After New Delhi, we have to find a completely new strategy. They in the south. We in the north.’Footnote 14

Attempts to transform the structures of global trade in favour of developing countries thus resonated with activists in Europe, where a host of groups had been devoting their attention to issues such as emergency relief, the problems of development, transnational solidarity and notions of global citizenship since the 1950s. The appeal of the Third World to European radical groups has drawn most attention.Footnote 15 However, the coalition which emerged around the issue of fair trade at the end of the 1960s is just as remarkable for the broad range of groups it managed to integrate. Its supporters could be found among secular and Christian groups, radicals and moderates, young and old. Youth groups, student organisations, church groups and political parties found common ground. They were united by their concern over global tensions stemming from inequality and their frustration over results of intergovernmental negotiations.

In this sense, the new fair trade activism reacted to the emergence of a post-colonial world, which representatives of the global South, European politicians and fair trade activists alike attempted to shape.Footnote 16 Decolonisation and European integration impacted people throughout the world beyond the domain of international relations. These twin processes challenged them to regard their daily practices of production and consumption through a new prism. To people in Western Europe, the global and the European were intricately connected. Not only was the European Economic Community a crucial player in global trade, the existence of transnational governing institutions at the United Nations and European level also led fair trade activists to believe that swift and far-reaching changes to the system of global trade were within reach during the second half of the 1960s.

The new strategy that the Sjaloom group proposed aimed at changing public opinion by targeting not just politicians and administrators, but individual consumers as well. ‘It's about sugar and cacao. Including therefore any consumer of these commodities of world trade.’ By demanding to buy the products which were kept from the European markets by import tariffs and subsidies for European products, regular consumers would be able to make a difference. ‘At least by taking at face value what we have always been told: “the customer is king”’, Reckman exhorted, invoking a well-known post-war mantra of consumer society. ‘Well then, the customer king from now on demands cane sugar from his grocer’.Footnote 17

The repertoire of consumer activism thus became entangled with an attempt to impact politics at the European and global level. Taking up a tradition which had often been employed in supporting religious missions and campaigns for poverty relief, citizens were urged to put their power as consumers to use by buying specific products. In contrast to the charitable tradition, however, buying cane sugar was regarded as a symbolic, political act on behalf of people in the global South. The focus was not on the volume of sales, but rather on attracting the attention of the public. A group of predominantly leftist Amsterdam students ambitiously took up these ideas. Sugar had been one of the commodities brought forward time and again as an example of colonial exploitation and the following postcolonial trade inequality.Footnote 18 In the 1960s it was also a product which could, when imported from developing countries, make a real difference to their economic situation.Footnote 19

The students’ first attempts to sell cane sugar were well received. Emboldened, they formed a committee which planned a large-scale campaign for the autumn of 1968. After finding a wholesaler to provide them with the required amounts of cane sugar, gathering support from prominent figures such as the economists Jan Tinbergen and Gunnar Myrdal and devising promotional material, the committee was all set by the end of the summer.Footnote 20 In the course of these preparations, the social base of the campaign was decidedly broadened. The students reached out to political organisations across the party landscape, as well as contacting Catholic and Protestant churches and a host of other organisations. Notably, they also cut across age groups, involving a host of sympathetic people beyond their own years.

The cane sugar campaign marked the emergence of a movement promoting global fair trade. The emphasis on changing the structure of international trade was distinct from other initiatives which are now cited as early appearances of the fair trade movement, such as the arts and crafts shops in the United States and the Oxfam campaigns in the United Kingdom.Footnote 21 On 30 September 1968 the campaign officially commenced. Local action groups were provided with several ways to draw public attention to the issue of cane sugar and the inequalities of world trade. ‘The aim is to bring about a change of mentality, which will force the government, facing a new attitude among its citizens, to choose the side of the poor countries in international negotiations’, the campaign brochure stated.Footnote 22 Locally, the campaign groups reached out to churches, town councils, political parties, trade unions and many other contacts to promote their campaign. Individual consumers were asked to demand cane sugar at grocery stores of their own choice. Cane sugar was also sold door to door by some groups. Both organisations and individuals were called upon to substitute cane sugar for beet sugar, thus drawing attention to the global and European trade regulations which disadvantaged producers from the South.Footnote 23

The crucial role of the EEC was acknowledged from the start. In line with the aim of above all informing the public about the unfair structures of global trade, the campaign committee had devised well-documented promotional material. The activists’ background in a student movement which prized intellectual substantiation and their claim to expertise were unmistakable. The brochure which informed the public about the issue took clear aim at Europe right from the start: ‘They receive 15 cents per kilo of sugar, we pay 60 cents per kilo of sugar on export subsidies’, it stated. ‘The EEC-countries should admit the cane sugar producing countries to their markets’, the brochure's authors continued.Footnote 24 On page after page of documentation the role of the EEC was considered. The attitude of the EEC-members during the UNCTAD negotiations on sugar had been ‘bewildering’. They had demanded a special position for the EEC regarding production subsidies and import tariffs. Moreover, the subsidising policy and the protectionism pursued by the Community encouraged overproduction of European sugar producers, even as producers in developing countries were depending on their sugar exports to provide them with a dire-needed income. The EEC therefore acted ‘strongly inward-looking, selfish and short-sighted’, the authors concluded. National governments for their part hid behind their EEC membership, pledging their sympathy to developing countries whilst blaming European commitments for their lack of concessions.Footnote 25

The importance of European politics to the issue of global trade was reaffirmed as the cane sugar campaign met with considerable public acclaim without causing a corresponding political response. During a radio debate about the campaign, the labour politician Henk Vredeling noted his approval of the attempts to raise awareness about the inequalities of world trade and to encourage citizens to take action themselves. As for the political consequences, however, he deemed the influence of Dutch officials very limited. Their earlier attempts to improve European agricultural policies had proven ineffective, Vredeling noted. He therefore took issue with the campaign's predominantly local and national organisation. A European issue had to be addressed on a European scale.Footnote 26 Even those less sympathetic concurred. Dutch sugar producers countered the campaign with a brochure of which 50,000 were sold and another 120,000 distributed for free.Footnote 27 It regarded the problem of inequality in the global sugar trade as a problem beyond the reach of Dutch consumers. What was needed, according to the Dutch sugar industry, was a more effective system of global regulations.Footnote 28

Aiming for Europe

Realising that the national governments of European states were bound by common agreements regarding international trade, the cane sugar campaign took aim at European economic policies in particular. All the ingredients for a successful internationalisation seemed to be in place: the sugar trade was a distinctly international phenomenon. Sugar was one of the few commodities for which a functioning framework for international trade was in place at the end of the 1960s. The fact that the trade was regulated both at an international and a European level would guarantee activists a common target. Along with international governing bodies such as UNCTAD, European integration thus fostered the hopes for ‘grand politics’ by providing activists with a target that held the promise of far-reaching change at short notice. The cane sugar campaign therefore focused on a European public and was accompanied by the attempt to establish a network which would be able to support a Europe-wide campaign.

The proliferation of the cane sugar campaign across Western European countries was attempted by Dutch activists from early on. During the national demonstration held in December 1968 at the seat of the Dutch government in The Hague, protesters carried English-language signs to reach out to an international audience (see figure 1). In January 1969 the campaign's secretariat drafted an English letter which summarised the goals, the concept and the practical opportunities to participate in the campaign. This first letter was sent to around 1,000 international contacts.Footnote 29 From then on such letters were regularly updated and sent out across Europe. By the end of 1970 the activists proudly presented the results of their attempts in the Netherlands to those interested abroad. They claimed that the campaign had received ample attention across Europe. The key publication issued by the activists had sold 40,000 copies and the consumption of cane sugar had doubled since 1968. On the other hand, the political pressure exerted by the campaign had only been ‘moderately successful’. Although the Dutch Parliament had expressed sympathy for its goals, it had not undertaken any concrete actions. The European Parliament and the EEC Commission had considered the issue as well, but without tangible consequence. ‘Changes in the EEC sugar policy are unthinkable unless there is political pressure in the other member countries as well’, they urged those who received their letters. By then, the coordinating committee estimated around 2,000 international contacts had received information about the campaign.Footnote 30

Figure 1. Members of the cane sugar campaign addressed an international audience at a rally in The Hague, 3 December 1968.

The attempts to publish the initiative across the Dutch border had some effect. In 1969 the World Council of Churches in cooperation with the oecumenical Committee on Society, Development and Peace recommended the initiative as an example of how churches could become involved in action for economic justice.Footnote 31 The ‘Working Congress of Action Groups on International Development’, in Egmond aan Zee at the beginning of April 1970, was a next attempted step towards internationalisation. The conference was hosted by X min Y, a Dutch initiative for self-taxation on behalf of developing countries which had emerged from an earlier Sjaloom campaign. The invitation had brought together some eighty activists from all over the world, most of them based in Western Europe, to gather at a holiday resort owned by the Dutch social democratic trade union federation. Participants travelled from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, England, France, West-Germany, Italy, Peru, Sweden, Switzerland and Yugoslavia to bring about ‘internationalised development action’.Footnote 32 The set-up of this international gathering of activists was remarkably similar to that of the international meetings such as the UNCTAD conferences: after a general assembly, smaller groups would discuss specific issues. These eventually reported back to the general assembly. Amidst debates about several aspects of development action such as education and political pressure, liberation movements and strategies for development, the viability of internationalising the cane sugar campaign was discussed in a section on consumer action.Footnote 33

Among the participants discussing development activism were delegates from both European and developing countries, most notably the Latin American Christian democratic trade union leader Emilio Máspero. Together they identified several factors which complicated the cane sugar campaign. The final report pointed out the appalling conditions of workers procuring sugar cane and the fact that the production was mainly controlled by European firms. The campaign would thus have to include attempts to pressure these firms in order to improve the working conditions in the sugar cane industry. Secondly, the section report noted that if the production of cane sugar was indeed controlled by Western firms, an increase in profits on cane sugar would not benefit the people of developing countries. A third concern the participants had brought forward was that if the production of sugar in Europe was not decreased, substituting the European consumption of beet sugar for cane sugar would lead to a dumping of the European sugar surplus on the international market, resulting in lower prices for cane sugar as well. Therefore, the campaign would have to aim at reducing the production of sugar in Europe in order to achieve its aims. Finally, the report recounted that the campaign could strengthen the economic ties between unequal partners. The dependency of the weaker partners in this relationship had been exposed during earlier economic crises, during which their products and services had been less sought after. In other words, development action should aim to increase the independence of developing countries, not their dependence on rich countries.Footnote 34

Despite the criticism, the meeting ended with a discussion of the concrete possibilities for the internationalisation of the campaign. The participants agreed to exchange information relevant to the campaign. They decided to pursue actions to pressure the EEC members to sign the International Sugar Agreement, which they had not done up till then due to the incongruity between the aims of the international deliberations and the EEC policy on sugar production. The applications of four new members to the EEC were deemed an issue deserving joint action in order to prevent these countries from gaining admission ‘at the expense of underdeveloped countries’. In conclusion, the participants agreed on the need to find an institution capable of coordinating international activities and the desirability to focus on sugar as a first topic of joint consumer actions.Footnote 35

During the conference a plan was launched to create an international secretariat. The Third World Centre of the World Student Christian Federation in Geneva was proposed as its location. Eventually, however, representatives of X min Y tasked themselves with hosting the international correspondence.Footnote 36 During the months after the meeting they pushed for the rapid establishment of an international sugar campaign, seeing as though negotiations concerning UK accession to the EEC would soon commence.Footnote 37 International coordination proved almost impossible. The pace of the negotiations could hardly be reconciled with the practical challenges of coordinating a host of activist groups throughout Europe. The first step towards a joint campaign was to be an open letter by the supporting groups to representatives of the ten governments involved in the negotiations, the EEC Council of Ministers and the European Commission. The letter urged the negotiating parties to consider the interest of the South in their decisions. It was eventually presented on 21 July 1970, with signatories from all countries involved except Norway and Luxemburg. Their transnational coalition had not managed to initiate many local and national events in support, however.Footnote 38

The ambition to organise a second wave of Europe-wide activities in the autumn of 1970 also proved too ambitious. Instead, Dutch representatives of the cane sugar campaign and British members of the World Development Movement met for bilateral consultation on the cane sugar campaign.Footnote 39 Members of the World Development Movement presented Prime Minister Edward Heath with a heart of cane sugar in November, just as their Dutch counterparts had done two years earlier. The World Development Movement called attention to the fate of the sugar producers within the UK Commonwealth. Due to the United Kingdom's planned accession to the EEC, the cane sugar imports to the United Kingdom from Commonwealth countries such as Barbados, Jamaica, Fiji and Mauritius were threatened to be substituted by the sugar surplus produced within the EEC.Footnote 40 At the same time, local groups distributed leaflets and over 200,000 packets of cane sugar among the public, held sugar tasting competitions and addressed their members of parliament on the subject.Footnote 41

The protest against the effects of gaining admission to the EEC for sugar cane farmers demonstrates how the opposition against joining the EEC forged an unstable amalgam of – among others – conservative nationalists, Commonwealth business interests, trade unionists concerned about job security for British sugar industry workers and Third World activists pragmatically trying to salvage the privileges of former UK colonies.Footnote 42 This coalition was especially uneasy for the latter activists, who found themselves cooperating with business representatives they would usually oppose. According to Clifford Longley of The Times, the World Development Movement was quietly supported by the Commonwealth Sugar Exporters’ bureau and its powerful director John Southgate.Footnote 43 Paradoxically, Third World activists thus sided with the sugar industry, trying to uphold a system of preferences based on colonial ties.

Europe divided activists as much as it united them. European political and economic integration provided them with a common cause, but the relevant time tables and political priorities diverged considerably between different countries. The difference between the initial approach followed by the Dutch cane sugar campaign and its subsequent UK follow-up struck the members of the transnational coalition which had been forged in Egmond aan Zee. Whereas the Dutch campaign had aimed to change trading policies, the British version attempted to retain the favourable conditions under which former UK colonies exported sugar to the United Kingdom.Footnote 44 Nevertheless, the pioneers of the transnational cane sugar coalition urged likeminded activists to support the UK campaign. They could lend it additional weight by sending and publishing letters to stakeholders, demanding an explanation for the lack of a response to the previous open letter and reiterating their request to consider the interests of the South during the negotiations.Footnote 45

Not much pressure was needed to persuade the UK government to place special emphasis on the future of the Commonwealth sugar production within the EEC. Next to New Zealand dairy products, sugar was a crucial issue for government negotiators.Footnote 46 To the dismay of many cane sugar activists, the Commonwealth countries accepted the result of these negotiations, which included a substantial commitment by the UK government to import cane sugar in the years following its admission to the EEC.Footnote 47 Europe remained a prime target in the protesting activities of the World Development Movement. A nationwide advertisement in 1972 called on the public to ‘help turn Europe inside out’, because it – among other things – denied free entry to the European market for cane sugar from developing countries. Europe was ‘keeping them poor’ (see figure 2) through its trade policies, whilst the UK government neglected the interests of the poorer members of the Commonwealth.Footnote 48

Figure 2. World Development Movement, ‘Keeping Them Poor’

The coalition with those critical of UK EEC membership and the World Development Movement could therefore persist beyond the process of negotiations. The issue of cane sugar remained valuable to the movement both as a concrete bond between their campaign and the workers in the sugar industry, and as a highly visible example of the inequality of international trade. Moreover, it was relatively easy to find support because the interests of British workers and those in developing countries could at least rhetorically be united, whilst a foreign ‘Europe’ could be presented as the main problem. In 1973 members of the movement joined workers of the cane sugar refining company Tate & Lyle in a march of about 2,000 people to protest the fate of cane sugar in the United Kingdom after it was granted EEC membership. Whilst the workers were primarily concerned with their own job security in an industrial branch which had come under increased pressure by Common Market regulations, World Development Movement activists stressed the needs of workers in developing countries, who also depended on the United Kingdom importing sugar cane. The protesters united behind slogans like ‘keep the cane’ and ‘beat the beet’ (see figure 3).Footnote 49

Figure 3. Tate & Lyle Sugar Workers Demonstrate Alongside World Development Movement activists.

The developments in the United Kingdom epitomise the integrating and the disintegrating role Europe played. The battle against the EEC united those focused on the potential loss of jobs in the United Kingdom with those concerned by the trading position of the developing countries across Europe. At the same time, the relations of British activists with development advocates in other European countries were hindered by the issue of the EEC, not just because the British activists claimed a special position for developing countries from the Commonwealth but also because activists from the latter countries regarded such a position a neo-colonial arrangement. The distinct timetable of the UK negotiations also impeded the coordination of a joint European cane sugar campaign, which had been planned for 1971.

As the initiative in the United Kingdom proceeded, so did preparations elsewhere. The international secretariat reported first local actions in Belgium and the translation of the booklet on cane sugar into German in November 1970. Activists in Italy, France and Denmark had also been in contact about setting up a campaign.Footnote 50 The West German campaign was planned by members of Aktion Selbstbesteuerung.Footnote 51 Elaborating on their plans, Werner Gebert of that organisation recalled how Dutch activists had presented their initiative at the international congress and proposed to transform it into an international campaign in order to effectively challenge the sugar policy of the EEC. Even though British fellow activists had had to start their campaign earlier, the international campaign remained desirable according to Gebert, precisely because the sugar trade was a subject concerning all EEC member states. Moreover, the focus on sugar would raise awareness of international inequality among the general public and help those affected by this inequality to better understand its nature.Footnote 52

Like in the UK campaign, West German activists adopted the ideas, the repertoire and even the literature which had initially been developed in the Netherlands. These similarities between the campaigns in several European countries and the transnational network sustaining them suggest that they should be regarded as a transnational campaign. The members of the West German preparatory group planned to sell or hand out bags of cane sugar, accompanied by informative flyers, eye-catching posters and possibly also street theatre and audio messages. However, the packaging and distributing of a sufficient amount of cane sugar to support such an undertaking was not possible at the time of writing in early 1971. The ambitions voiced by the initiators thus hardly matched their means. Attempts to bring large organisations in as participants had failed. Gebert stated that he expected churches, trade unions and large charity organisations to be interested in participating based on the goals to which these organisations subscribed.Footnote 53 The optimism about launching the cane sugar campaign in West Germany was shared by fellow activists in the Netherlands, who – alluding to the German word for cane (Rohr) – expected the Ruhrgebiet to be turned into a Rohrgebiet. Footnote 54

Even though the initiative drew interest from several sides, the West German cane sugar campaign appears to have been crowded out by other initiatives and lacked the support of resourceful organisations. Members of the Aktion 3. Welt Handel, who coordinated many initiatives to promote fair trade with the aid of the main churches, signalled that they had no capacity to participate.Footnote 55 Among the leadership of the Protestant churches, the question whether such local initiatives should be supported to promote development was only decided in 1973.Footnote 56 Many like-minded activists were sympathetic to the initiative, but this did not translate into tangible financial or personnel support.Footnote 57 Still, the campaign mustered around 10,000 signatures for a petition addressed to the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation.Footnote 58

Considering these difficulties, it must have been quite a surprise to hear the cane sugar campaign suddenly mentioned in the Bundestag. On 16 June 1972 the West German minister of economic cooperation Erhard Eppler had to answer questions on the issue. Gerd Ritgen, a Christian Democrat expert for agricultural policy, demanded to know whether Eppler's department had subsidised Aktion Selbstbesteuerung to help set up a cane sugar campaign. Eppler – who was renowned for his Third Worldist sympathies – replied that funds had been provided to Aktion Selbstbesteuerung, but not for this campaign. Ritgen pressed Eppler: did the minister regard sugar a product fit to exemplify the need for a change in the relations between developing countries? His answer was telling for the fate of the campaign. Although sugar cane was indeed a product which could easily be produced by developing countries, Eppler noted, the EEC had already decided not to allocate any more agricultural plots for beet sugar, so that developing countries might cover possible rises in demand for sugar. Moreover, although the sugar industries in developing and developed countries had severely competed over sugar markets during the 1960s, the global sugar market had been marked by scarcity and sugar prices had accordingly notably risen during the last years.Footnote 59 Even though the campaign had not achieved a significant change in European sugar policies, sugar thus no longer provided a suitable rallying point. The complexities of the global sugar trade, the technocratic and distant nature of European economic policies and cane sugar's loss of symbolic value combined to deflate the campaign.

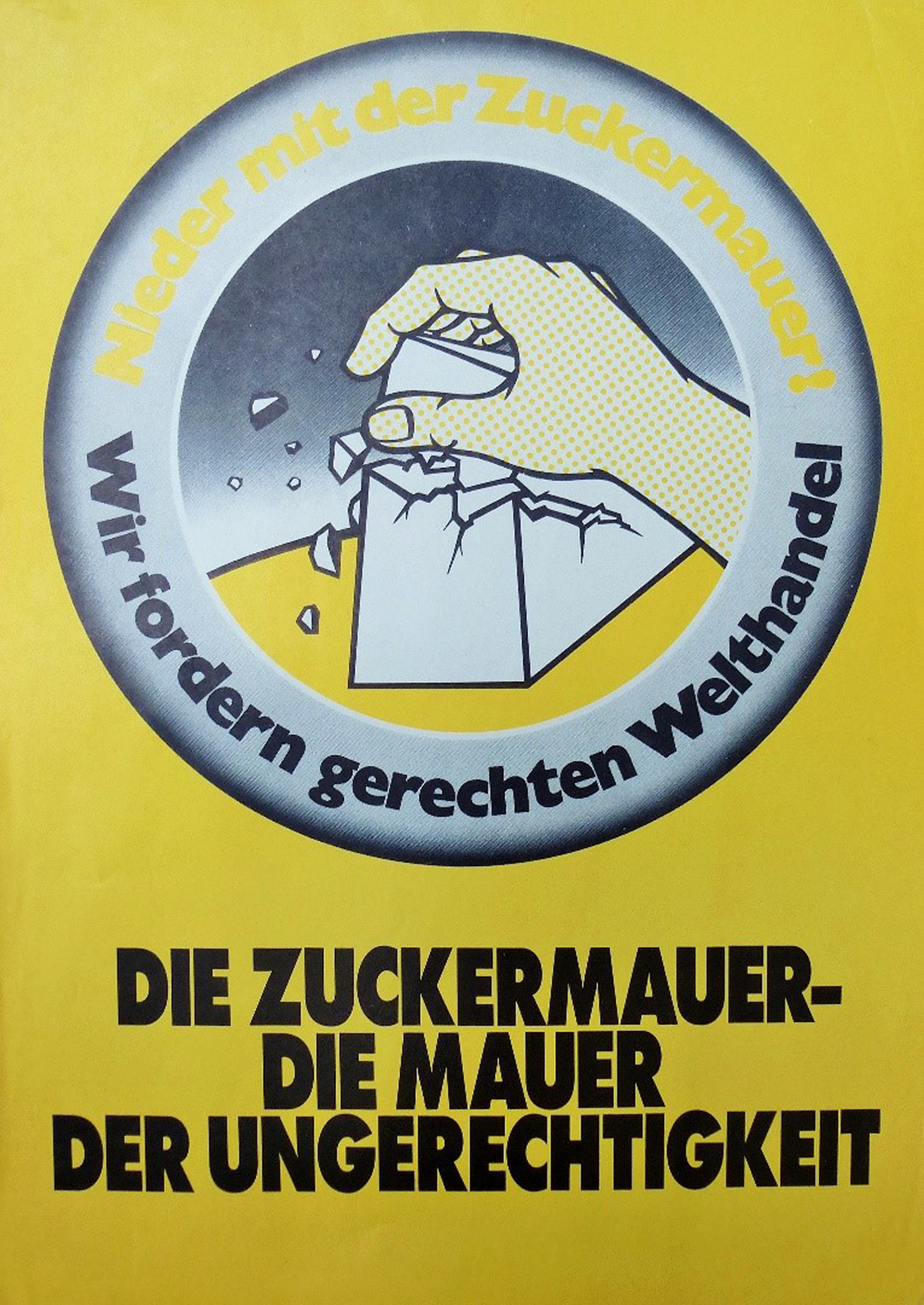

Figure 4. The German cane sugar campaign distributed a poster which critised the European tariffs on cane sugar as ‘a wall of injustice’.

Taking Root: Towards Local Action

European politics lost its appeal to activists as the cane sugar campaign waned. The European network which had been established, however, continued to function around new ideas and repertoires of action, which often shifted the focal point of social action towards the local level. The circumstances which had made cane sugar appear as an ideal subject with which to illustrate the imbalances of global trade gradually evaporated around the turn of the decade. First off, there was little room to pressure European policies, which were technocratic and removed from the national political arenas in which the campaign primarily operated. Many national governments were themselves critical of the creation of surpluses subsidised through the EEC's agricultural policies. During the 1970s a possible shortage of sugar was the bigger concern for these governments. As a result, the EEC continued to buy large quantities of cane sugar from developing countries after the entry of the United Kingdom in 1973 and the renegotiations with the associated developing countries in 1974. Moreover, the skyrocketing sugar market prices made consumers in EEC countries beneficiaries of the existing sugar regulations. In 1968 consumers could be roused by the notion that they were made to pay prices which were well above those at the world market. During the 1970s the contrary was true: sugar prices within the EEC were markedly lower, whilst the sugar shortages which were felt in other parts of the world were also kept at bay.Footnote 60

A third problem with sugar as a focus for fair trade activism was the relatively unique position the product held in world trade. Sugar was one of the few products for which effective international market regulations were in place. It was also one of the few primary commodities which did yield a good return on the world market during the 1970s. It thus could not illustrate one of the main problems of developing countries, which usually had to sell their primary commodities at steadily decreasing prices, whilst paying relatively increasing prices for the industrial products they imported from richer countries.Footnote 61 As the developmental ideal of an international division of labour – which would have led to an increase of international interdependency to the benefit of all – was replaced by the ideal of self-reliance and the accompanying diversification of national production branches, the focus on importing cane sugar from developing countries gradually lost its appeal.

A strong focus on sugar also seemed less and less attractive, as the exhaustive attention to the subject brought to light several other complications. For example, much of the cane sugar sold in the Netherlands turned out to be imported from Surinam, then still a part of the Dutch commonwealth. There was all the more reason to be critical about this relation because the sugarcane plantation was owned by a Dutch company, which thus benefited from the campaign more than Surinam workers did.Footnote 62 A group of agricultural students from the Dutch city of Wageningen, which was particularly active in this debate, pointed out that selling cane sugar from developing countries would only make farmers in those countries more dependent on the West, whilst it also pitted Dutch activists against farmers in their own country, although these were also victims of a capitalist mode of production.Footnote 63

Cane sugar's loss of persuasiveness was also part of a larger crisis of the approach to fair trade. The great expectations for a transnational resolution to unequal global trade evaporated, whilst the notion that cane sugar could substitute beet sugar to the benefit of all was no longer tenable. Searching for an alternative vantage point, some fair trade activists adopted a radical perspective, which departed from the notion of increasing mutual interdependence. Instead, people in the First and Third World were regarded as united in their struggle against their mutual oppressors, the capitalists. For instance, a group of former cane sugar campaigners in the Dutch city of Amstelveen in 1975 came up with the cane-beet campaign (riet-biet-aktie). They offered cane sugar and beet sugar for sale at a local shopping centre. Their stall was accompanied by noticeboards informing the shopping public about the reasons for and against buying cane sugar. In ensuing conversations with passers-by, the group members attempted to make clear how farmers and other ordinary people in developing and developed countries were both victims of the capitalist system.Footnote 64 Even though this view was able to set aside local and translocal differences, the ideological radicalism and the lack of nuance implied was rejected by many fair trade supporters in what had overwhelmingly started as a reform oriented movement.

Rather than clinging to sugar, however, most fair trade activists moved on. A broader outlook had been a staple of the movement even as it had prioritised the cane sugar campaign. A number of different issues and approaches had been presented at the congress in Egmond aan Zee. Consequently, the international secretariat of development activists which had been established there mustered several other attempts at coordinated actions after the joint cane sugar campaign failed. One and a half years after the first meeting, ninety representatives of ‘Third World countries’ living in Europe, Western European action groups and international organisations met for consultation in the Belgian town of Dworp in November 1971.Footnote 65 They decided that the secretariat would not take a leading role in setting up activities. Rather, it would serve as a channel to provide like-minded groups throughout Europe with information and contacts.Footnote 66 Two new attempts at coordinated international action did follow: led by the World Development Movement, associated members tried to define a common approach for the third UNCTAD meeting in Santiago de Chile in 1972. A year later a delegation of development action groups met with members of the European Commission in Brussels to talk about the relation between an enlarged EEC and the Third World. Associated groups were asked to accompany this occasion with actions to draw additional attention to the meeting.Footnote 67

The meetings and communications which were facilitated by the international secretariat did not achieve a new joint campaign because of the diversity among the associated groups.Footnote 68 They did, however, play an important role by disseminating ideas and models for local and national actions. During the 1971 meeting in Dworp, the U-Gruppen from Aarhus presented a campaign which had aimed at fostering awareness about the relation between the EEC and the Third World among the local population through a combination of distributing leaflets and engaging people in personal conversations.Footnote 69 Another model presented in Dworp was the Dutch ‘world shop’. In the Netherlands many local cane sugar groups had followed up by setting up such a world shop, in which information was exchanged, campaigns were planned and several products from developing countries were sold in order to support producers from the South both practically and symbolically. This model of action attained remarkable resonance. In the Netherlands ten world shops joined forces in a national organisation in 1970. By 1972 it already had 120 members in 1972.Footnote 70 Many of these shops continued to sell cane sugar, but this was only a small part of a wide range of different activities deployed by local world shop groups. Abetted by channels such as the international secretariat for development action groups, the model quickly spread through Europe.

Whereas the U-Gruppen and the world shops prioritised local action, they also served as springboards for campaigns on a larger scale. The circular letters issued by the international secretariat called attention to several of those. Turning away from attempts at quick, large-scale change through international politics, these campaigns often targeted specific countries, companies or promoted specific products. For example, the circular called attention to a boycott of coffee from Angola and the boycott of Outspan oranges from South Africa.Footnote 71 Many moderate fair trade activists prioritised selling products made by cooperatives in the South, whereas radical activists pragmatically opted to support producers from leftist states such as socialist Tanzania and Sandinist Nicaragua by selling their products in the North. Moderate and radical activists alike thus predominantly opted for specific campaigns, at once focusing and broadening the scope of the fair trade movement. The economic development of the South continued to dominate the agenda of the movement, but instead of promoting a reformed system of global trade, activists emphasised the empowerment of individual producers or progressive countries. The conclusion which moderate and radical activists had reached during their international consultation in 1971 remained a guiding principle: ‘whatever is planned during this consultation, in the end it has to be directed towards the goal of changing the structures within the industrialised capitalist countries and the Third World’.Footnote 72

The Legacy of the Cane Sugar Campaign

In the light of the trajectories of global solidarity, the demise of the cane sugar campaign around 1974 is as telling as its original success. The latter highlights the close relation between global and European politics for activists concerned with fair trade around 1968. Social activism in the late 1960s was inspired by the possibility of a change in global politics which the decolonised countries appeared to initiate. Supporting this goal, activists deliberately took aim at European politics. The initiators successfully built on intergenerational collaboration, broad coalitions of groups concerned with global development and, increasingly, transnational exchanges. Evidently, a broad segment of the Western European public shared a concern over establishing fair conditions for trade with the Third World. However, the Europeanisation of fair trade activism proved much more difficult than could have been expected. Although the campaign could be judged a success regarding its diffusion, visibility and support across Western Europe, a comprehensive campaign failed to materialise. Neither did the activists succeed in noticeably impacting European economic policies.

The eventual demise of the campaign presents a story of disillusion and evolution. In the end, the attempts to launch a Europe-wide campaign failed because European integration did not firmly align activists across Europe. Attempts to address global and European politics also failed to register a meaningful response. Campaigns directed at specific companies, causes and producers such as the Dutch boycott campaign against selling coffee from Angola in the early 1970s, the international campaign against Nestlé from 1977 onwards and the alternative trade to support Nicaragua during the 1980s did produce tangible results.Footnote 73 Many activists therefore decided to follow this course during the first half of the 1970s. Initially, the post-colonial politics of international trade and development had aligned these activists with the agenda of global and European politics. Their eventual disillusion led to a disconnection between civic activism and the transnational political domain. As a New International Economic Order and a green revolution in agriculture were discussed in the hallways of United Nations’ institutions and national agencies, development activists turned their attention to markedly different issues.

The history of the cane sugar campaign thus tells the story of the demise of ‘grand’ political activism. This demise was not a turn towards apolitical or strictly local activism. Rather, it produced a different kind of political activism, which introduced a broader perspective. A European network of world shops, alternative trading organisations and related development action groups emerged. These integrated a vast array of issues ranging from protest against multinational companies, Apartheid, colonial regimes and gender inequality into the movement. At the same time, this new activism shied away from grand visions of swift political transformation in favour of an approach which targeted specific issues and aimed at incremental change. By building up a local presence, fair trade activists ingrained the issue of global economic inequality deep into the fabric of Western European societies during the 1970s. This continuous local presence would eventually also provide the movement with a stepping stone as it mustered new attempts at more ambitious national and international campaigns during the 1980s and 1990s. The European networks of world shops and alternative trade organisations engaged in a search for a more professional approach to their trading practices during the 1980s, leading up to the establishment and diffusion of fair trade certification since 1988.

Finally, the rise and demise of the cane sugar campaign calls into question our understanding of the spatial dimensions of civic activism. Europe was important for fair trade activists engaged in the campaign since the 1960s on several levels. Common economic policies prompted activists to initiate a campaign which targeted European politics and to build up a network of like-minded citizens within the countries involved. Even though European integration provided activists with a shared frame of reference, it did not simply replace local and national concerns with a new, shared perspective. Different local and national groups of activists had different stakes within the process of European integration. Their views of Europe and the world continued to interlink with local and national viewpoints. The rise of European and global frameworks of governance rather forced citizens to find new balances between local and translocal spaces.Footnote 74 Their actions rendered European and global institutions more visible in daily life, but the emphasis on these perspectives could rise and fall. Activities such as the cane sugar campaign show how Europe and the world at once functioned as integrating and disintegrating frameworks among European citizens and changed civic activism in unexpected ways.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was conducted with the support of the Dutch Research Council (NWO).