Introduction

In the spring of 1972, two women concerned with the environment analysed the contents of a bin bag to trace waste streams in the Netherlands. The garbage inspection of the two women activists – Babs Riemens-Jagerman and Miep Kuiper-Verkuyl – would form the basis of widespread glass recycling in the country. Only a few months later, these same Dutch women had a large container placed in the centre of their hometown for empty bottles. Soon, action committees in many cities followed. Thanks to this achievement, the Netherlands became the first Western European country to collect glass separately.Footnote 1 Within six years, glass recycling containers dotted the entire country. Today, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium, Sweden and Switzerland boast Europe's most successful programmes, with a glass recycling rate of 90% or higher.Footnote 2 Why households, usually women, are willing to take on the responsibility of returning glass without any financial gain has puzzled the environmental movement, the glass industry and government officials. It is the key issue in our article.

The recycling container has come to symbolize the environmental movement of the 1970s.Yet, the willingness of users to return glass successfully was not a given at all. As the Norwegian brothers Petter and Tore Planke discovered when they sought to export their electronic bottle deposit machine, the Tomra, to the United States, the success depended on a subtle negotiation among users willing to carry empty bottles, grocers’ search for a solution for empty-bottle logistics, bottlers looking to open markets, a glass industry in need of raw material and law makers responsive to the outcry over littering. Their high-tech Tomra had been successfully developed in the Scandinavian context of thrift since 1973 and had been exported all over Europe. It failed, however, in New York State, where recycling was associated with poverty rather than with good housekeeping and responsible citizenship. The Tomra company ascribed their failure in New York to what they perceived as the dearth of thrifty housewives willing to return bottles – combined with the hordes of homeless and the Afro-Americans [sic] who, they believed, recycled bottles to earn money. The company had assumed that the thriftiness of Scandinavian women was a given all over the world.Footnote 3

Our article argues that the rapid success in the Netherlands cannot be explained by the political context of the 1970s nor by the glass industry's interests alone. Although the women activists tried to reinstate the more ecologically sustainable bottle return system, their actions focused on the most politically feasible goal of recycling.Footnote 4 We suggest that a critical mass of citizens began to resist emerging consumerism thanks to a strong social tradition rooted in a culture of thrift. Many citizens experienced the announcement of an abundance-and-waste economy as an assault on their values. As one protagonist of our story articulated the sentiment of her time in 1973, she hoped for a future with ‘less squandering of resources and energy [and] less greed’.Footnote 5 Others expressed their concerns in less lofty and more prosaic terms. They put their revulsion against the ‘throwaway-society’ down to wartime scarcity. When asked what prompted their activism, they pointed to their wartime experiences.Footnote 6 A 1985 nationwide survey of 20,000 households confirmed that the generation most disciplined in recycling was born before the war and had come of age during the German occupation.Footnote 7 Indeed the war, rather than ecological awareness, goes a long way to explain the individual commitment of middle-class citizens to the environment. What interests us is why 1970s women activists took on the individual responsibility of recycling without any financial reward.

We show how in the decades before environmental activism took centre stage, well-articulated and institutionalised politics of waste collection and recycling had already profoundly shaped a culture of austerity, conservation and thrift. As we will argue, Dutch middle-class housewives, well-organised politically, had been socialized in the practice of reuse and recycle from the early 1930s until the mid 1960s. With their initiative to collect glass separately, the two women were thus mobilising for the new cause of environmental protection an older tradition and morality of saving. While US President Richard Nixon's establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency and the European Conservation Year, both in 1970, signalled a transatlantic exchange of ideas, we show that the deeply ingrained mentality of thrift, the historic ties to Nazi Germany's autarky policies and the relatively late emergence of consumer spending better explain the relatively fast popularisation of separate waste collection in the Netherlands compared to other Western European countries.

Two women, one plan

In 1972, the first Dutch glass container was installed in Zeist, a small but affluent, middle-class town in the heart of the Netherlands (Figure 1). Two women, Babs Riemens-Jagerman and Miep Kuiper-Verkuyl took the initiative after completing a five-day women's leadership course on environmental hygiene. Riemens and Kuiper had much in common. As full-time housewives, they volunteered in community and church work and were connected to the international YWCA (Young Women's Christian Association). They not only shared concerns about increasing environmental pollution, but both their husbands were well informed about the alarming research data on the environment. Riemens's spouse worked at the national institute for environmental management; Kuiper's husband was affiliated with the agricultural division of the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research, TNO. As they recalled in an interview two decades later, both women were acutely aware that most scientific reports on the subject simply ‘disappeared in drawers’.Footnote 8 When Riemens and Kuiper heard about the leadership course on the environment, they applied.

Figure 1. At the initiative of women activists of the Zeist Milieuzorg, the first Glass Recycling Container was placed near the supermarket in Zeist, The Netherlands. De Nieuwsbode, 7 June 1972.

The organiser of the course was Elisabeth Aiking-van Wageningen, an early environmentalist. Although deeply impressed with Rachel Carson's seminal book Silent Spring (1962), and President Kennedy's committee investigating the impact of pesticides on health and the environment and its subsequent critical report of the industry and lax government policies, Aiking found her moral anchor in the Bible. Based on the theological doctrine of humans’ responsible stewardship of the earth, she shared the notion that Christians have an obligation to maintain rather than exploit the gifts God has bestowed on mankind.Footnote 9 Aiking had served on the board of the International School of Philosophy in the Catholic town of Nijmegen, which taught people's individual responsibility in sustaining the quality of life. Having witnessed the fast increase in household waste in the late sixties, she came to realise there was an urgent need to translate academic and ethical concerns to daily practices.Footnote 10 And middle-class women, in their role as household managers, were best positioned to turn the tide, she believed.

Aiking was not alone in her concern for the environment. Nor was her belief in women's moral compass and special role in helping social change a novel one. The country's largest women's organisations like the Dutch Association of Housewives (Nederlandse Vereniging van Huisvrouwen), the Federation for Female Voluntary Aid (Federatie voor Vrouwelijke Vrijwillige Hulpverlening) and the Dutch Household Council (Nederlandse Huishoud Raad) all dealt with issues related to ‘civic housekeeping’. Going back to the nineteenth century, civic housekeeping was the belief that women had a special moral role to play in stemming the excesses of industrialisation; many women's organisations sponsored subcommittees on environmental pollution. The committees kept abreast with scientific journals on chemistry, discussed academic calculations on the relationship between demographic data and the country's waste and eagerly shared the evidence-based information with their rank-and-file members.Footnote 11 Moreover, these mid-level women shared the belief in science as a powerful tool of persuasion and for effecting social change. Thus Aiking's far-reaching initiatives targeting women as a means to raise public awareness on environmental issues fell on fertile ground.

Aiking was politically well connected and went on to found the Organisation for Nature and Environment (Stichting Natuur en Milieu), the country's largest environmental organisation combining several initiatives, before becoming adviser to the minister for the environment (1973–7).Footnote 12 In 1969, she lobbied the vice president of the consumers’ union (Consumentenbond) to pay more attention to environmentally safe ways to grow food. She had also lobbied P. Lichtenstein, procurement manager of the up-and-coming supermarket chain Albert Heyn, to either abolish the recently introduced disposable glass bottles or have retailers collect them. Lichtenstein turned her down. He feared the storage costs would be prohibitive. Undeterred, Aiking broadened her crusade by deciding to explore grass-roots activism. She organised free leadership courses on environmental hygiene for women's organisations in the hope they would share the insights with their respective constituencies. Women, she believed, ‘viscerally know how “precious” life is . . . [and] through them, one reaches the entire family. Women talk about these things with their husband and children. That is the way to reach the entire population. For men, it is difficult because they are away during the day. But one reaches them through their wives.’Footnote 13 Women were thus the key actors for social change.

With her academic, government and institutional connections, Aiking gained direct access to a high-ranking official at the Department of Culture, Recreation and Social Work (Cultuur, Recreatie en Maatschappelijk Werk – CRM), responsible for the Dutch participation in the 1970 European Council's Nature Conservation Year. With his help, Aiking received a substantial subsidy for the women's leadership course, which was the Ministry's contribution to the European initiative. To provide a proper institutional base, Aiking established the Foundation for Environmental Protection (Stichting Milieuzorg) together with her friend, Maaike van Palland, the wife of biologist and environmentalist M. F. Mörzer Bruyns, the country's first professor of conservation at Wageningen University.Footnote 14 The initiators also used the government funding to support existing environmental protection initiatives.

For the course, Aiking mobilised a group of concerned academics who had been writing on environmental themes for some years: D. J. Kuenen, zoologist at Leiden University; C. J. Briejér, former director of the Ministry of Agriculture's Department of Plant Diseases and 1967 author of a book that, like Carson's Silent Spring a few years earlier, warned how chemicals entered the food chain; and J. Weits, director of Amsterdam's food inspection service.Footnote 15 The course took place in April 1970. Arranged over five successive weeks, the weekly workshop attracted over 300 mid-level representatives of women's organisations. Participants were asked to sign a form confirming their willingness to ‘make an effort to the best of their abilities to disseminate the knowledge obtained during this course’.Footnote 16 Officially sanctioned with a speech by the nation's first female minister Marga Klompé (of CRM), the course included lectures on various aspects of environmental degradation, but also focused on water, air and soil pollution, food control, and the effects of the environment on children's development.Footnote 17 Aiking urged the mid-level female leadership to engage officials in their local communities whenever possible. She counselled women against too much assertiveness to avoid antagonizing authorities. To reinforce the leadership strategy, all participants were grouped together regionally on the final day of the course to expedite future co-operation, networking and direct action.

Aiking's mission succeeded in at least one case. After the course, Riemens and Kuiper decided to join forces. Aiking's non-confrontational and diplomatic tactic appealed to them both. It was in sharp contrast to a younger generation of activists entering the public arena, who deliberately provoked reactions from authorities through ‘direct action’ against what they called ‘the system’, a political tactic so successful in the American civil rights movement; they despised the collaboration with authorities that Aiking advocated.Footnote 18 In contrast, Aiking, Riemens and Kuiper represented a long tradition of the conservative wing of the women's movement, subscribing to the notion that women had a morally superior role to play in fighting social injustice and moral decay. They felt uncomfortable with the 1970s progressive feminists, who rejected women's special place and instead called for sexual equality. Aiking's approach resonated with middle-class women because she managed to link abstract environmental concerns to their daily experiences. She mobilised the earlier practices of saving, self-discipline and prudence. Representing the Dutch Association of Housewives, Elizabeth Boon-Reuhl, who had a PhD in biology but stopped working when she married, urged her members: ‘Housewives of the Netherlands, unite, together with the Centre for Environmental Protection, in caring for your family, your household and your environment!’Footnote 19

Riemens and Kuiper first considered focusing on traffic problems to tackle growing pollution. After reading about waste problems in a popular scientific journal, however, they settled on the issue of household waste.Footnote 20 Inspired by this article, they analysed a bin bag's contents to understand the various categories of waste and their potential for reuse. The subsequent report of their analysis became the first memo in the town's local organisation for environmental protection (Stichting Milieuzorg Zeist en Omstreken, SMZO). The memo discussed the ‘frightening problem’ of millions of nylon stockings being thrown out annually and how to solve the problem of waste by turning old glass into ‘glassphalt’ for example.Footnote 21 Although they merely took note of the glassphalt technique, the possibility of reusing glass continued to preoccupy the two women. The memo was the start of the organisation's long-term focus on glass, representing the first systematic attempt to reintroduce a longstanding collective practice of waste recycling that had recently been abandoned.

When questioned about their activism many years later, Riemens and Kuiper explained that the growing waste went against everything they stood for. ‘Having been through the war, we just couldn't stand this kind of waste.’Footnote 22 Born in 1919 and 1927, they articulated a widely shared feeling that formed the moral anchor of their generation. The experience of hunger and poverty constituted a moral affront against throwing away potentially useful products. One lecturer at the leadership course in 1972 compared the growing urge to consume with the German invasion in 1940. He characterized both as a foreign attack on ‘feelings of safety and security in honourable traditions’.Footnote 23 As we will see, ironically, those honourable traditions had been reinforced, if not introduced, by the Nazi regime decades earlier.

Mobilising war practices for a new cause

The waste container activism of Riemens and Kuyper was rooted in the tradition of the culture of thrift. That culture had been reinforced by the state-sponsored policies to deal with shortages during the 1930s Depression and the German occupation. The First World War had been a dress rehearsal; during the economic depression state policies of encouraging thrift and reusing materials became more organized; during the Second World War and the German occupation those policies became systemic.Footnote 24

In the case of the Netherlands, the government elected to promote thrift rather than raise wages and consumer spending. For example, authorities sponsored home economists to teach working-class and farmers’ wives to produce good meals with little money, to preserve the summer's harvest and the winter's slaughter, to use material from old clothes to make new ones, and to produce their own mattresses filled with straw.Footnote 25 From 1938 on, governmental organisations and private companies started to amass raw materials.Footnote 26 A national policy sought to redistribute waste (both industrial and household) to various branches of industry.Footnote 27 In 1939, the policy established semi-independent national bureaus for each branch of industry that forced companies to seek permission before they could ‘use, buy, sell or transport any raw materials’.Footnote 28 During the Second World War, these practices were intensified in the Netherlands as in France and became more systematic once the German authorities exported their autarkic policies to the occupied countries. In this radically changed political context, the German authorities sought to support their war economy by collecting household waste in Europe's occupied countries. In the summer of 1940, Hans Heck, Reich Commissioner for Scrap Salvage, reorganised salvage operations in the Netherlands and Belgium based on the German model, before going to France a year later.Footnote 29

The Nazi policy first introduced in Germany during the Four-Year plan in 1936 sought to create an autarkic economy in which consumer demand was restrained and wages held down to pay for rearmament. The ongoing shortage of raw materials and Germany's search for independence from international markets generated a policy that put much effort into developing novel reuse and recycling techniques. The autarky policy created an ‘all-embracing recycling system’.Footnote 30 In June 1937, Hermann Göring declared that Germany ‘could not afford the luxury of letting anything end up in the dustbin. Even the last piece of wood, paper or bone – everything will be used’.Footnote 31 Nazi recycling policies, however, were not motivated by nature conservation interests, but by the regime's need for economic independence to finance a war economy.Footnote 32

The German autarkic policy reserved a key role for housewives, rallying school children and youth organisations. In their propaganda campaigns against waste, Nazi policy makers produced board games and postcards to mobilise as many girls and housewives as possible.Footnote 33 The focus on women and children went hand in hand with the regime's eradication of the private waste management sector dominated by Jewish middlemen, a policy the Nazis exported to all the countries it occupied in Europe.Footnote 34 Germany's pursuit of autarky was in sharp contrast with US and British government policies, which chose Keynesian economics as the road towards economic recovery, encouraging export and trade with other nations and increased domestic consumption.Footnote 35 The Dutch government led by Prime Minister Colijn held on to the gold standard, however, restricting consumption for the poor, while encouraging spending for the upper classes. Nevertheless, the Dutch, like the French, British and US governments never developed a national policy for recycling waste.Footnote 36

Soon after occupying the Netherlands, the German authorities instituted a systemic recycling policy. Immediately, articles appeared in various Dutch newspapers entitled ‘Using waste: neglected reserves’, explaining that people could no longer afford to throw away valuable resources. From then on, the Dutch would have ‘to follow the example set by poorer people’, whose practices would teach them that ‘hardly anything is useless’.Footnote 37 In previous years the Dutch press, just like their French counterparts, had closely followed and published items on Nazi waste and recycling policies by which German households were forced to use three dustbins: one for undifferentiated general waste, one for metal-containing waste like cans and toothpaste tubes, and one for food remains. Dutch newspapers also devoted many pages to the relationship between food waste and its potential for raising pigs.Footnote 38 A few months after the invasion, in August 1940, the Germans established the Dutch-run National Bureau for Old Materials and Waste Products (the Bureau, hereafter) in The Hague. The Bureau organised waste collection, ordering collectors to sell their products for nationally set prices. It also instructed housewives how to pre-sort their waste for easy industrial processing, how to reuse as much material as possible, and how to produce and conserve whatever scarce resources they could. Large-scale propaganda efforts were implemented to teach women how to make preserves and jam or how ‘to make the humble potato more attractive’. Germany's efforts to reuse old materials and waste products were welcomed by the Catholic weekly De Tijd: ‘One of the good things these awful times might bring us is the systematic frugality of using old materials.’Footnote 39

At first, the Bureau co-ordinated the extraction and production of new materials from rags, old paper and used metals for Dutch industries. It sought to mediate between German demands to extract as much (processed) raw material as possible for Germany and for the needs of Dutch industries. Dutch producers frequently referred to the Bureau's policies as ‘plunder’.Footnote 40 But as Chad Denton has astutely analysed in the case of occupied France, local authorities working under German directives were also eager to erase the German origins and hide the purposes of the policy.Footnote 41 In the Netherlands, the director of the All-Dutch Bureau similarly stressed that its interests lay primarily with Dutch industry. During the first years of the war, Germany's governmental commissioner in the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, sought to accommodate a Dutch-oriented policy because he needed to win over the Dutch for the national socialist cause.Footnote 42

At the start of the war, Dutch municipalities, except for Amsterdam, hardly had any experience in sorting and reusing old materials. The German initiative to sort waste at source – that is before rather than after putting it in the rubbish bin – was a new concept for Dutch authorities. On 5 October 1940, the German authorities issued a new law (Decision on Waste/Afvalbesluit) which brought private – often Jewish – waste collectors under the authority of local governments now responsible for collecting, separating and recycling potato peelings, vegetable refuse and bones for the production of cattle feed. Like their German counterparts earlier, Dutch housewives were ordered to collect paper, rags, rubber, metal, leftovers and human hair; in June 1942, glass was added to the list.Footnote 43 A month later, when the regime sought to further ‘cleanse’ the sector of Dutch Jews and thus ‘Aryanise’ it, the decree ran into problems. In large cities like Amsterdam and the thinly populated northern areas, the restrictions on Jewish waste collectors caused the sector's collapse; a similar situation had arisen earlier in Germany when the businesses of lower-class Jews unable to flee the country had been pushed out of the sector and their owners deported to the camps (Figure 2).Footnote 44 In April 1943, when the deportation of Dutch Jews was in full swing, the Bureau stepped up its campaign, demanding that Dutch citizens deliver their separated household waste to licensed waste collectors. Each collector controlled a neighbourhood covering about 6,000 residents and was tasked with collecting the listed materials weekly. Following a strict distribution plan, the collected materials were supplied to Dutch industries. To the great annoyance of Dutch people working with the Germans, the waste was exported in growing amounts to Germany as the war progressed. Although precise figures are unavailable, we know that in October 1942 one-third was exported to Germany.Footnote 45 Again we find a parallel situation in France and Norway, suggesting that German policies were depoliticised by national actors to better suit local circumstances.Footnote 46

Figure 2. Jewish peddlers dominated the trade of reused materials like this man at the second-hand market Waterlooplein trading bottles, textiles and a typewriter in Amsterdam in 1925. When Germans occupied the Netherlands they were replaced by non-Jewish citizens. Waterlooplein 1925, Nationaal Archief/Spaarnestad Photo/Het Leven.

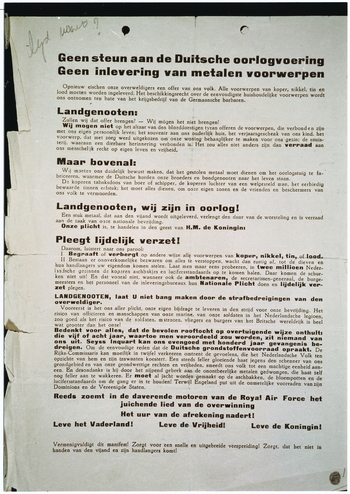

The policy in the Netherlands shifted alongside the changes in German politics. When taking over the Ministry of Armament in February 1942, Albert Speer expanded his role in the economy and curbed Seyss-Inquart's authority over the Netherlands. Now directly controlled from Berlin, the Dutch Bureau's mandate became to maximise ‘the Dutch contribution to the German war economy’.Footnote 47 Consequently, the proportion of Dutch national income that went to Germany without compensation grew from 19% in 1941 to 40% a year later.Footnote 48 The waste export policy to Germany resulted in the Bureau's bad reputation for what it called ‘the foolish, ill-founded anti-propaganda . . . that collected cans are to be reused for the production of guns’.Footnote 49 Indeed a resistance movement poster illustrates evidence of opposition to this policy. ‘No support for the German war machine. No surrender of metal objects’, an illegal resistance poster urged Dutch citizens to fight the occupation by refusing to recycle old material (Figure 3).Footnote 50 Bureau officials attempted to counter public resentment, arguing that most waste benefited Dutch factories. ‘In those factories, Dutch workers earn ‘a decent wage’ and through Dutch traders, their products are brought to Dutch families. If there is a truly national interest these days, it is without doubt the act of saving these socially valuable materials.’Footnote 51 Although essentially true, the waste collectors were obliged to sell their goods to the Bureau, which only paid them half what they would get by selling their products (illegally) in Germany: the price control encouraged a black market and sabotage of the Bureau's measures.Footnote 52

Figure 3. Resistance movement poster calling Dutch citizens to defy German recycling policies. Geen steun aan de Duitsche oorlogsvoering. Geen inlevering van metalen voorwerpen. Verzetsmuseum, Amsterdam.

To meet the new demands from Berlin, the Bureau put extraordinary effort into propaganda to increase waste collection, targeting women in particular. Co-operating with the Economic Agency for Information (Economische Voorlichtingsdienst), the organisation distributed 40,000 posters. The print media regularly published articles on the Bureau's activities. The Bureau toured the country, lecturing on the economic necessity of separate waste collection, presenting collections of ‘old materials and what can be made from them’ and collecting papers from ‘old archives that have become useless’.Footnote 53 From December 1941 onwards, Jewish rag collectors were forbidden to carry out their trade.Footnote 54 In the autumn of 1943, as the majority of Jews had been deported, the Bureau went on the offensive, organising a week-long programme in thirty-five towns with advertisements in local newspapers, flyers, a lecture, a film and an exhibition to ‘drive public opinion in the right direction’.Footnote 55 Housewives were instructed that reusing materials was ‘not just a legal duty, but also a moral obligation for mothers to teach their children not to be negligent with food or throw away waste that could be used for feeding animals, as if it was useless’.Footnote 56

The efforts to target lower-class women combined pre-war methods of the home economics movement and government campaigns to beat the Depression.Footnote 57 To reach as many women as possible, the Bureau was present at trade fairs and worked through national women's organisations. The head of propaganda criss-crossed the country, visiting primary, secondary and domestic science schools as well as theatres and businesses. Everywhere, he lectured on collecting, separating and recycling waste. Afterwards a film was shown with the telling title of a popular Dutch proverb: ‘Whoever fails to appreciate the little things, is not worth the larger ones’ (Wie ‘t kleine niet eert, is het grote niet weerd). He declared: ‘People have to get used to keeping and regularly separating waste materials.’ Thus, the Bureau worked relentlessly at convincing Dutch housewives how important their waste-collection practice was for the economy.

Only a well-functioning organisation could ensure that ‘the smallest and dirtiest piece of cloth’ and ‘every shred of used paper [to be saved] economically, dry and clean’ could be recycled, the agency argued.Footnote 58 Many different types of waste had to be collected separately before being sent to the rag-and-bone collectors. The organisation faced a challenge. Urban residents in small apartments had a hard time storing separate rubbish bins. One woman, describing herself as someone ‘willing to contribute her share of raw materials’, wrote to the Bureau saying she was ‘racking [her] brains on how to separate different kinds of waste’.Footnote 59 The Bureau believed the best solution to such practical issues was even more propaganda, labelled as ‘education’. The director defended the policy saying: ‘people need to be educated in how to value waste materials’. Like his colleagues in France, he also sought to downplay the German origins of the policy and offer nationalist arguments: ‘Recycling old materials is not a wartime phenomenon, but also necessary and economically profitable in peacetime. Our national industries will benefit as well, more jobs will be created and our trade will profit.’Footnote 60

Dutch housewives were urged in even more direct terms: in return for potato peelings that farmers use for animal feed, women would receive ‘[what] they as urban residents could use so well: milk, meat, fat and other animal products’.Footnote 61 This mobilised an earlier practice of exchanging urbanites’ potato peelings for farmer's milk: it visualised the food chain from production to waste and back, urging housewives: ‘Save your potato peelings. The cow turns them into milk for your children.’Footnote 62 Posters showed how bones were rendered into soap, how old toothpaste tubes were used to produce new ones and how a smiling housewife was happily separating her waste in different containers, under the motto: ‘it doesn't matter how you do it, as long as you regularly store and sort your waste’.Footnote 63

The policy succeeded especially in large cities, with the Bureau claiming it collected one kilo of food waste per capita per week in 1943.Footnote 64 The Bureau also urged the public to save non-organic waste: ‘every housewife ought to see with her own eyes what enormous value used cans, rags and old paper have for our national industry, especially nowadays. She ought to see how the collected amounts are recycled into all sorts of new products she lacks herself because shopkeepers receive so few of them.’Footnote 65 Instructive figures emphasised the immense effects of small deeds: ‘Our four largest cities, together producing 2,000 tonnes of waste per week, are able to feed 10,000 head of dairy cattle.’Footnote 66 And although ‘human hair is not a goldmine, our country supplies at least 3,000 kilos of hair a week, which at 0.15 cents per kilo, amounts to 450 guilders weekly and 23,400 guilders annually for our traders – an amount we ought not spurn, a nice bonus.’Footnote 67 The waste industry's trade journal (Afvalstoffen) explained to traders how they could instil in housewives the urgent need for separate glass collection, concluding ‘the housewife therefore does not only fulfil her duty, but achieves an important task by keeping and delivering broken glass: neither small nor large traders should neglect the collection of glass, because meaningless pieces generate work for thousands of workers, both in glass and other industrial sectors . . . In this way they protect the amount of raw materials still available in our country; they help us to make use of them as long as possible.’Footnote 68 Just like their German sisters, Dutch women were regarded as the main foot soldiers of autarky and preservation.Footnote 69

The agency also directed propaganda campaigns at children, developing a new curriculum for secondary schools called ‘waste economics’.Footnote 70 From September 1942, students were urged to participate monthly in collecting old paper. With 330,000 children at 22,000 schools, the action was fairly successful.Footnote 71 The agency produced new course material for schools and posters explaining the importance of rag and paper recycling, offering a collection of objects made from old materials as visual aids for displaying in schools, theatres and shop windows. The Bureau distributed door-to-door pamphlets and posters; it produced a booklet entitled ‘Are you participating?’ and created a mascot, a factory-girl called ROMEA, the Dutch abbreviation for the Bureau.Footnote 72

As the war continued, the shortages became more acute. Compared to 1941, the amount of waste collected decreased further from 47.50% to 40.92% between 1942 and 1943.Footnote 73 The Bureau thus faced an increasingly large challenge. While recycling more, households produced less waste than before the war and recyclable materials that were less valuable than before the war.Footnote 74 Particularly in the winters of 1944 and 1945, urban consumers increasingly relied on older methods like cooking in hay boxes, conserving fruits and vegetables and spinning wool; they learned to discern what materials objects were made of and how to transform them into useful items; they transformed tapestry into a hat, a lampshade into shoes and lamp wicks into sandals.Footnote 75 Housekeeping became more of a science and more labour intensive. In large cities, the burden for housewives grew heavier. The rationing of fuel and foodstuffs, the use of surrogates and the never-ending search for alternatives determined women's daily routines. Nothing could go to waste.

The Nazi-inspired waste policies thus shifted the burden from a professional and private sector that provided income for an overwhelmingly Jewish proletariat to a non-professional army of schoolchildren, charitable organisations, youth clubs and women who worked for free (Figure 4). The new household task of waste collection, separation and delivery did not engender personal pleasure and increased housewives’ workload in particular. More importantly, housewives internalised the personal responsibility of saving that the Nazi policies had instilled when the Nazis were enforcing the implementation of the dual policy of autarky and exterminating Jewish citizens.

Figure 4. The propaganda poster admonishing housewives to separate waste, warning ‘You will be fined for this! And the waste service will not collect it!’ Poster 1942. Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam.

After defeating the Nazi regime, the United States turned West Germany into its showpiece in the cold war, radically reversing what had gone before as tension with the Soviet Union grew. Under US tutelage, West Germany abandoned the autarkic policies, abolished rationing and adopted Keynesian policies starting in 1948. The Dutch, Austrian and British governments continued rationing until the mid 1950s, however. In the Netherlands, the last rationing measure was abolished in 1955 when people could finally buy coffee without ration cards. Many European governments resisted the Marshall Aid emphasis on consumption and in some instances even lowered wages. Not till 1963 did the Dutch government allow incomes to rise as a means of stimulating the economy.Footnote 76 Thus in contrast to West Germany, the politics and practice of frugality remained in place for two decades after the war ended. As the Netherlands had been one of the most war-devastated countries in Western Europe, the government's rebuilding efforts focused on investing in heavy industry while continuing with rationing, keeping wages down and discouraging consumption up to the mid 1960s. This anti-consumerist policy was much to the chagrin of US Marshall Plan policy makers.Footnote 77

In other words, waste activists Aiking, Riemers and Kuipers came on the scene less than seven years after the fundamental policy shift away from encouraging saving to spending. The first signs of consumer society became visible only after decades of intensive government-sponsored socialisation into a deeply ingrained morality of thrift. Given this context, it is not surprising that expressions of consumer culture were contested almost from the start. As early as 1970, an astounding 96.2% of citizens favoured a more stringent and restrictive environmental policy.Footnote 78 This also explains the remarkably strong Dutch response to the alarming message in the Club of Rome's report.Footnote 79 The media reported disquieting news about the deteriorating state of water, air and soil; environmental action committees sprang up throughout the country while feminist and traditional women's organisations rallied to the cause. Headlines regularly referred to the academic issue of ecological deterioration in terms of individual household duties rather than state or market responsibilities: ‘Housewives determine waste-mountain heights’; ‘Housewives in action against the use of plastics’; ‘Sorting waste at home is no big deal'; ‘The customer can become king again: reuse your household materials.’Footnote 80 Although most people embraced economic growth, the new culture of abundance also made them feel slightly uncomfortable. This discomfort was centred less on consumer goods than on squandering materials without using them again. Throwing away valuable materials contradicted the politics of frugality and moralities of thrift that Dutch housewives had internalised for at least four decades.

New wine in old bottles

In the tradition of moderation and individual responsibility resulting from the Depression and intensified during and after the Second World War, Riemens and Kuiper sought to encourage self-discipline in citizens’ behaviour and the taking of individual responsibility. They were not alone. The Dutch Association of Housewives worried about the ‘overwhelming assortment of plastic cartons for ice-cream, yoghurt and puddings as well as plastic shopping-bags, spray cans and phosphate percentages in washing powder’. Its Amsterdam division lobbied local trade and industry to change their range of packaging and cater to the increasing number of environmentally aware consumers.Footnote 81 Riemens and Kuipers were particularly successful in their lobbying effort through bringing together three stakeholders: individual consumers, government agencies and industry. Following Aiking's non-confrontational and institutional approach, they involved industry and appealed to women's personal responsibility. This winning combination contributed to their success.

Riemens and Kuiper were well aware that industry was facing a growing amount of waste that could generate a valuable source of income.Footnote 82 Although they professed their real goal had been to reinstate the more environmentally sustainable bottle deposit system, they sought out industrial partners by contacting transport companies and waste processing industries and by attending conferences like the Research Consultancy against Environmental Pollution Congress in 1972.Footnote 83 There, Riemens met two men who would play important roles. T. Krijgsman, director of Utrecht's sanitary health department and representative of the Dutch waste community, had a keen interest in how to reduce household waste. The second was an official at one of the country's largest trucking companies in the port of Rotterdam: Maltha. The company transported glass waste for the glass-processing industry and leased small deposit containers to individual citizens for recollection. Maltha's quest to expand glass collection had become more acute since the mid 1960s when, despite resistance from women's and consumer organisations, beverages like milk were increasingly sold in cartons instead of glass bottles, reducing the amount of glass available for recycling.Footnote 84 Exploring alternatives to increase glass collection and promote recycling, the firm approached the Ministry of Health and Environmental Hygiene for door-to-door collection, but was turned down because of the projected high costs.

The women's next contact was glass factory De Maas in the town of Tiel. They learned that to produce 1,000 kilos of new glass, the industry needed either 1,250 kilos of raw materials or 1,000 kilos of glass fragments. When interviewed two decades later, the women recalled that these astonishing figures, combined with their discovery of the various stakeholders with a keen interest in glass waste, gave them a great boost to continue their investigations. When Riemens and Kuiper contacted Maltha to explain their plans to collect glass for recycling, the company officials responded enthusiastically. However, they had a keen interest in glass recycling rather than reintroducing the glass deposit system the women were advocating. Riemens and Kuiper quickly adapted to the company's preference because they were pleased to see that Aiking's plea to lobby rather than confront industry had worked. To what extent the co-operation between citizens and industry bothered the activists or amounted to sheer co-option of the ecological movement, as Samantha McBride has argued for the success of recycling policies in the United States, is not clear from the sources. We do know their action was not without controversy in the consumer union.Footnote 85

Maltha advised the two women from Zeist to ‘go about it on a large scale’ and offered the firm's delivery and pick-up service for the deposit containers.Footnote 86 Although Zeist Council initially responded hesitantly, the glass industry and transport companies provided the opportunity to make the initiative commercially viable. But the companies also warned they would only participate if Riemens and Kuiper could guarantee a critical mass. After more intense lobbying by the two women, the town council finally issued a permit for glass collection once the local Albert Heyn supermarket agreed to a deposit container on its premises. The supermarket only agreed on the condition that the women supervised the operation, ensuring that the container would be used during daytime only, that the site was kept clean and that the glass was picked up by the transport company on time. On 30 June 1972 the first Dutch glass recycling container was ready for use, marking the first installation of its kind in Western Europe. In short, thanks to a plain, grey container with sliding lids, the two women from the town's local organisation for environmental protection, SMZO, breathed new life into an old industrial network of shop-owners, bottle cleaning services, transport companies and glass-producing industries that had been dealt a severe blow by the introduction of the milk carton and the decline of deposit bottles.

Soon similar initiatives developed elsewhere. Within weeks, the Zeist organisation was flooded with requests for information; the women received over 600 phone calls and letters, mostly from women in the country's Protestant north, where environmental awareness with its emphasis on personal responsibility resonated apparently more than in the Catholic south.Footnote 87 Three major factors played a role in the women's success. First, Riemens and Kuiper appealed to women's responsibility as in charge of running the household. They referred to the issue as personal ethics: ‘Finally, an opportunity to relieve our conscience a little: we no longer have to throw things away. Things can be used again! Truly a first initiative towards a new policy: Sensible Saving (zinvolle zuinigheid).’Footnote 88 Secondly, they creatively applied the principles of Aiking's leadership course in Utrecht. In closing the recycling cycle, they successfully involved key stakeholders: local authorities, business players and women volunteers. Thirdly, they succeeded because the glass industry was suffering from rising costs as a result of the abolishment of the glass deposit system following the bottling industry's successful lobby. Glass producers were keen to apply the more cost-effective methods of reusing glass waste as an alternative to the bottle deposit system.

Similar initiatives emerged in urban communities such as Leiden and Utrecht. In Rotterdam, the mayor's wife, An Thomassen of the Labour Party, lobbied the city council and transport company Maltha. She mobilised key people in the council and thereafter Rotterdam began collecting glass in an open container in October 1972. Women living near the recycling container who were active in women's organisations took the responsibility of supervising the site and keeping it clean. The Rotterdam initiative succeeded on an even grander scale: within five months the number of glass containers in the city had risen to fourteen.Footnote 89

When other municipalities followed the Zeist example, the government began to believe that collecting glass should be a state responsibility. Health Minister Dr L. B. J. Stuyt proposed reintroducing the deposit system. Yet the glass industry's umbrella organisation, the combined glass factories (Gecombineerde Glasfabrieken), objected, following the international trend of the industry. They lobbied for, and ultimately won, what they called ‘recirculation’ as opposed to the bottle deposit system.Footnote 90 Three months after Riemens and Kuiper initiated the first glass container in Zeist, the Minister reconsidered his earlier call for the bottle deposit system and wrote to all Dutch communities, instructing policy makers to support local initiatives seeking to recycle waste materials rather than reintroduce the old deposit system. He cited the Association for the Removal of Waste's investigation in the town of Amersfoort (Stichting Verwijdering Afvalstoffen; SVA – a government-sponsored organisation investigating and advising on waste issues) on recycling possibilities.Footnote 91 Soon afterwards, many municipalities near Leerdam, site of the country's main glass factory, installed glass containers.

While idealistically driven (female) citizens carried out the experiment in Zeist and Rotterdam, the government in collaboration with the SVA took on that role in Leerdam. By the end of 1976, the SVA had approached the provincial government of North Brabant to start a glass-collecting experiment. With a new labour government in place, the Ministry of Public Health and Environmental Hygiene subsidised and further professionalised the sector.Footnote 92 In these newer initiatives, collection points were no longer near supermarkets or shopping centres, but in residential areas. Industry and local government embarked on a large-scale promotional campaign, distributing scores of stickers, posters and pamphlets. A woman from the provincial capital Den Bosch officially operated its first glass container on 27 May 1978, a date erroneously entered in the annals as the country's first recycling container.Footnote 93

Although the government and the glass industry were fully involved, the success ultimately rested on Dutch women's willingness and eagerness to collect empty bottles and jars separately on behalf of the environment without the benefit of the older deposit system's financial reward. They were willing to bear the burden and carry the extra weight of bottles in an additional bag when shopping. The economic reasons for saving materials had gone. Instead, women's motivation to act thrived on the morality they had learnt to internalise during decades of governmentally sponsored thrift and frugality right up to 1963. After the summer of 1972, the collection of glass continued to be professionalised on an ever-larger scale. Ten years later, there were about 12,000 containers dotted around the country. And in 1981, 27% of the glass produced came from recycled glass; seven years later, this rose to 52%, making the Dutch glass industry Europe's leader in glass recycling.Footnote 94

To summarise, the quick acceptance of glass recycling containers in the Netherlands shows how the ideology of environmental awareness and engagement was built on the tradition of thrift and reuse. No longer economically necessary, the practice of reusing glass was so deeply ingrained in women's daily routines that new arguments to reconstitute old habits hardly needed to be explained or sold. In a country where generations were raised hearing their parents’ remarks about the war, the revolt against throwing away food or useable materials had become a moral imperative that the actions of the two pioneering women mobilised for a new purpose. They matched the spirit of the time: growing prosperity generated joy and comfort, but also a widely shared sense of discomfort. Consumer society not only damaged the environment, it was also considered, harking back to older moralities, morally inappropriate. Religiously anchored in the belief that the earth is God's creation and needs careful tending, the two women successfully addressed their financially comfortable middle-class supporters in 1972 by evoking thrift and frugality and by appealing to their individual responsibility: ‘the treasures of this earth are finite . . . Thrift is needed [in little ways too] . . . Wie het kleine niet eert, is het grote niet weerd.’ The same motto used during the German occupation in the Second World War to mobilise women to collect their waste separately for recycling was being repeated to bring women into the fold for the new ideology – the environment.

Since then, Dutch glass recycling systems have been extraordinarily successful. Along with Switzerland, Belgium, Austria and Sweden, the Netherlands has established highly effective recycling programmes. The discussion does not stop here, however. Recently, the recycling of PET bottles (recyclable bottles made of Polyethylene terephthalate, sometimes PETE) has been hotly contested, pitting the industry against municipal communities over exactly the same issues: one-way or returnable systems. Again, the issue at the top of the agenda is who is responsible for waste.Footnote 95 No matter the outcome of the struggle among local government, the state and industry, individuals (usually women) are once again seen by all as the premier group to shoulder the heavy burden of environmental concern and practice.