Introduction: Looking for Creative Colonial Governance

In 1936, Luigi Federzoni, president of the Italian Senate, published an essay for Foreign Affairs under the title ‘Hegemony in the Mediterranean’. In it, he dispassionately assessed the manner in which Italy's imperial claims conflicted with those of France and of the United Kingdom.Footnote 1 Official circles in these three countries would easily endorse, at the time, Federzoni's main point, that the future of the relations between the three Western European powers would be played out in the Middle Sea, as the point of physical contact between their colonial empires.Footnote 2

After the settlement of the First World War, the three former allies consolidated their position in the Mediterranean and shared the last spoils of the Ottoman Empire. France, already in control of Algeria (1830–48), Tunisia (1881) and Morocco (1912), acquired a mandate over Syria and Lebanon from the newly created League of Nations. The United Kingdom received a similar mandate on Palestine, adding to the string of territories it already governed in the Middle Sea (Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt, Cyprus). Italy solely obtained, with the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, the international validation of its, by then, eleven-year occupation of the archipelago of the Dodecanese. It was a comparatively meagre addition to its dependencies in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, where, moreover, ‘pacification’ was never fully achieved before 1931. This discrepancy would fuel the resentment of Italian nationalist circles protesting against a mutilated victory (vittoria mutilata) and inspire the revisionist agenda of the fascists, especially in the 1930s, once Mussolini felt he had built his ‘consensus’ for fascism in Italy itself.Footnote 3 Despite several appeasing attempts on the part of France and the United Kingdom, Italy pursued an active campaign of destabilisation in the Mediterranean following its conquest of Ethiopia and the proclamation of the Italian Empire (Impero italiano) in 1936.Footnote 4 This mainly consisted in poking the fire of anti-colonial resistance, which engulfed every single one of the above-mentioned colonial settings in the 1920s and 1930s.

A rich historiography has documented these geopolitical tensions.Footnote 5 What has not been systematically considered, however, is that dangerously unstable as it was, the Mediterranean in the interwar period was also a space of mutual observation, experimentation and occasional emulation between the rival imperial projects carried out by the three main European colonial powers. Such a ‘transnational construction of a science of colonialization’ took place in specific political and economic circumstances.Footnote 6 The creation of the League of Nations in the wake of the First World War impelled European powers to rebrand their imperial rule as trusteeship, a tutelage exercised over subject communities ‘until such time as they are able to stand alone’ and achieve independent statehood.Footnote 7 In addition, European powers faced social and labour unrest across their empires, which suggested the need to be economically more interventionist. Nonetheless, although intensely debated, mise en valeur, the economic development of colonised societies, seemed, for most imperial powers, elusive in the aftermath of the 1929 crisis. By contrast, in the 1930s, Italian authorities claimed to have obtained tangible results in this regard, ones that allegedly earned them the loyalty of their colonial subjects and certainly the interest of their rivals, specifically the United Kingdom.

This article will focus on British and Italian Mediterranean entanglements in a context of intense imperial rivalry around the cases of Cyprus and the Dodecanese. As two Eastern Mediterranean, post-Ottoman, multicultural provinces where Greek-Orthodox Christians, Muslims and, in the case of the Dodecanese, Jews lived together, these island settings were comparable and the challenges their administration presented seemingly similar. Yet it appeared to British authorities that their Italian rivals in the Dodecanese had been far more successful in obtaining the acquiescence, if not the consent, of their subjects, particularly of the Greek-Orthodox majority whose leaders, just like in Cyprus, had been strong advocates of enosis, or the political union with mainland Greece. This accomplishment they attributed to a governance that combined political authoritarianism with economic development, a method they sought to emulate in Cyprus. What they failed to see, or chose to ignore, was that fascist authorities used the Dodecanese as a testing ground for a far more ambitious vision of imperial rule. This vision drew on a specific chronopolitics, namely a complex of policy and discourse premised on the invocation of the Mediterranean's perceived Roman and Italianate legacy, essential to the legitimation of Italian rule and the ideal of modernisation, central in fascist ideology.Footnote 8 This in turn inspired a biopolitics, the representation of Mediterranean subject populations as embodying that past and as such worthy, for the greater part, of political and biological assimilation with the Italian metropole. In other words, the Italians used the Dodecanese to strategically blur the difference between rulers and ruled, to efface, to some extent, what Partha Chatterjee once called the ‘rule of colonial difference’, something their British counterparts never attempted in Cyprus.Footnote 9

This article draws primarily on the Italian archives of the ministry of foreign affairs but refers also to British official records as well as to the Cypriot and Dodecanesian press and, occasionally, to French and Greek official correspondence. Its broader aim is to engage a dialogue with the growing literature on imperial formations, which, in the wake of the work of scholars such as Ann Laura Stoler, Frederick Cooper or Martin Thomas, enjoin us to nuance the divisions between metropole and colony, nation and empire, or between supposedly distinct national styles of imperial policy-making.Footnote 10 Indeed this article proposes to explore interwar European colonial policy-making in the Middle Sea through a trans-imperial lens. It will thus highlight the role of consulates, intelligence agencies as well as direct contacts between British and Italian officials in the exchange of administrative practices and ideas across imperial boundaries and the formulation of an imperial rule deemed suitable to Mediterranean societies. It will also, however, remain attentive to the substantive differences between the settings under scrutiny. The first two sections of the article will bear on the changing geopolitical importance of Cyprus and the Dodecanese in the British and Italian empires respectively during the interwar period. A third section will focus on the alignment of British policy in Cyprus on that, Italian, in the Dodecanese while a last section will underscore the specificity and distinctiveness of the latter, with its emphasis on a particular fascist chronopolitics and biopolitics.

From ‘Pawns to Queens’? Consolidating European Sovereignty in the Eastern MediterraneanFootnote 11

The occupation of both Cyprus and the Dodecanese, by the United Kingdom and Italy respectively, had been a tactical move within larger geopolitical manoeuvres. In June 1878, the prime minister of the United Kingdom had obtained from Sultan Abdülhamit II the right to administer Cyprus as a means to honour his country's alliance with the Sublime Porte against the Russian threat. Italian forces had taken hold of the Dodecanese in May 1912 in order to force the Ottomans to yield, during their war of conquest of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. The fate of these islands had been put in balance several times thereafter. In 1915, the British foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey, had offered Cyprus to Greece, in exchange for that country's participation to the First World War. While the offer was rejected and never repeated, it did illustrate the fact that at least until that time, the island was, for British authorities, an ‘inconsequential possession’.Footnote 12 Under the pressure of Italy's wartime allies, Minister of Foreign Affairs Tommaso Tittoni had signed in 1919 an agreement with Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos providing that Greece would support Italian imperial claims in Albania and Anatolia and would in exchange be handed the Dodecanese, with the exception of the island of Rhodes.

The Greek-Turkish War (1919–22) and the final settlement of the ‘Eastern Question’ in 1923 transformed the position of Cyprus and the Dodecanese, within the British and Italian empires respectively. With the advance of Kemalist forces dispelling their plans of expansion in Anatolia, the Italian government officially denounced the Tittoni-Venizelos agreement in August 1922.Footnote 13 In the wake of the First World War, the United Kingdom had acquired League of Nations mandates over Palestine and Mesopotamia, carved out of the Ottoman Empire and consequently Cyprus became a useful link between Egypt and these new dependencies, a position that explained its ‘promotion’ to the status of ‘Crown Colony’ in 1925. Finally, in the July 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, that replaced the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, Turkish authorities renounced all claims on Cyprus and the Dodecanese.

These diplomatic decisions created an illusion of clarity that was all but denied on the ground. Conventional guarantees between the United Kingdom, France and Italy brought some limitations to these powers’ sovereignty over their Eastern Mediterranean possessions. Hence, article two of the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres provided that if and when the United Kingdom decided to hand Cyprus to Greece, Italy would do the same with the Dodecanese.Footnote 14 In addition, in article four of the 23 December 1920 Franco-British convention, settling the borders of the territories placed under mandate, the British government undertook to seek French approval before ceding Cyprus to any other power.

This mutually binding right of oversight was further complicated by the fact that the status civitatis, or political identity, of Cypriots and Dodecanesians remained in abeyance for quite some time. Both British and Italian authorities did take immediate steps to terminate the regime of capitulations until then in force. As the work of scholars on legal pluralism shows, unravelling what Will Hanley called the regime of ‘multiple sovereignties’, ending extraterritoriality (including jurisdictional immunity and tax exemptions) which benefited the citizens or protégés of different Western powers was a standard procedure whenever an Ottoman province fell under European control.Footnote 15 This, incidentally, induced many beneficiaries of this regime of exception to contemplate departure.Footnote 16 It did not, however, contribute to specifying the political identity of Cypriots or Dodecanesians, or the nature of their juridical link with their new metropoles. The United Kingdom had obtained from the Sublime Porte the right to ‘occupy and administer’ Cyprus, but Cypriots remained Ottoman subjects until 1914. They only acquired British nationality under the ‘British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914–1922’, after the United Kingdom annexed the island in retaliation for the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War at the side of the Central Powers. Dodecanesians, on the other hand, simply ‘remained Ottoman subjects until the coming into force of the [1923] Lausanne Treaty’.Footnote 17 For the time that it lasted, this indeterminacy challenged the exclusive jurisdiction, and therefore sovereignty, of the two colonial powers over both people and territory.

This became clear when Cypriots and Dodecanesians formulated claims over property located in other provinces of what used to be the Ottoman Empire and who, in order to maximise their chances at obtaining satisfaction, appealed to different governments, including that, much to the dismay of British and Italian authorities, of Greece.Footnote 18 In seeking ways to face this challenge, Mario Lago, the first governor of the Dodecanese to serve under the fascist regime, thus wrote, in 1924:

It would be interesting to see if similar cases of claims for properties belonging to inhabitants of Cyprus or of Arab countries detached from Turkey and located in Anatolia have emerged and the manner in which the French and British governments have decided to handle them vis-à-vis Turkish authorities. Indeed, and I wish to insist on this point, it is crucial to ensure that Dodecanesians do not get the impression of being less favourably treated than Cypriots, Syrians, Iraqis, Palestinians, etc., as this would, of course, harm our prestige.Footnote 19

The threat related to this jurisdictional ambiguity was compounded by the fact that in both settings, colonial authorities had to face an organised Greek irredentist movement promoting enosis, or the union of these islands to mainland Greece. In Cyprus, British authorities had created, for reasons this article will examine later, a series of institutions, which enabled secular and religious leaders of the Greek-Orthodox demographic majority to promote this ideology. In the Dodecanese, the confrontation between Italian military authorities and Greek-Orthodox community leaders over enosis was more violent, culminating with the ‘Bloody Easter’ of 1919 when a nationalist protest on Rhodes, the main island of the archipelago, ended with several casualties (including two fatalities) and with the deportation of the Archbishop of Rhodes in 1921.Footnote 20

If we are to believe the memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs, who served as governor of Cyprus between 1926 and 1932, the Italians had been much more resolute in meeting these apparent challenges to their sovereignty over the Dodecanese:

Under Fascist Italy Hellenism was being systematically and scientifically extinguished. The very name of Dodecanese, being Greek, had been suppressed and supplanted by Le Isole Egee, the Aegean Islands. Nationalities had similarly become religions; you spoke not of Greeks, but of Ortodossi, not of Turks but of Mussulmani. One Greek flag only floated throughout the Islands – upon the Greek consulate in Rhodes . . . [A]s the Italian flag was lowered at sunset all passers-by were compelled to salute it, stepping from their cabs or cars if necessary for the purpose.Footnote 21

Storrs had formed these impressions of Italian rule in the Dodecanese, which he contrasted with the ‘weak’ British regime in Cyprus, after an official visit to the archipelago upon the invitation of his ‘excellent friend’ and counterpart, Senatore Mario Lago.Footnote 22 Beyond Storrs's personal views, most British colonial officials were intrigued by what they perceived as a successful Italian method of administration in the Dodecanese. This interest, which persisted throughout the 1920s and even, despite growing diplomatic tensions between the United Kingdom and Italy, throughout the 1930s, translated into official policy changes in Cyprus.

Ruling over Mediterranean Societies

British interest for Italian governance in the Dodecanese derived from a number of factors, the most obvious being the assumption that Cypriots and Dodecanesians – as far as the local Greek-Orthodox demographic majorities were concerned – were ethnically the same. And while the Italians had adopted, as Storrs noted, a scrupulous policy of Italianising all toponyms (and patronyms) that sounded dangerously ‘Greek’, this did not change their impression, which they shared with their British counterparts, that they were dealing with a population that was for the most part Greek-speaking, Greek-Orthodox, with extensive connections, of a secular or religious nature, to Greek diasporic communities. In many ways, this perception had inflected, albeit in different ways, British and Italian rule in Cyprus and the Dodecanese respectively.

Hence in 1882, four years after their occupation of Cyprus, British authorities created a legislative council to which the islanders, separated in two electoral colleges, ‘Christian’ and ‘Muslim’, could return representatives. This, combined with the existence of liberal press laws and the fact that the administration of primary and secondary education was left in the hands of the leaders of the island's various religious communities contributed, as so many scholars have shown, to a profound politicisation of the island along nationalist lines.Footnote 23 Government officials went on record to justify this liberalism on account of the Cypriots’ ‘whiteness’.Footnote 24 Such representation was ideological, more than just rhetorical, but it was enmeshed with considerations of a broader geopolitical nature. Hence, Prime Minister Gladstone, responsible for granting Cypriots these trappings of democracy, had denounced the occupation of Cyprus by his predecessor, Benjamin Disraeli, as dishonourable.Footnote 25 Once in power, however, his government refused to return Cyprus to the Ottoman Empire, on the grounds that ‘[n]o Christian community has ever fallen back under Turkish rule, having once definitely [been] freed from it, since the [1683] siege of Vienna’.Footnote 26 Even against the background of such colonial racialist hierarchies, Cyprus's was an unusually liberal regime, comparable to those in force in Canada or Malta (the latter obtaining representative government in 1887). It was consistent, however, with that implemented earlier by the United Kingdom in another ‘Greek’ island setting, the Ionian islands, where a bicameral legislature existed under British rule (1815–64).Footnote 27

Italian perceptions of their Dodecanesian subjects were on the surface similar and similarly entwined with a broader geopolitical vision. Yet the practical implications of such representations were vastly different from the British case. Valerie McGuire shows persuasively how even prior to the Italian occupation in May 1912, the archipelago had featured prominently in the writings of leading nationalist intellectuals such as Gabriele d'Annunzio, Giuseppe Sergi, Edmondo de Amicis, Enrico Corradini or, later, Luigi Federzoni, as holding a possible solution to the Risorgimento's unresolved problem, namely the ‘Southern Question’. This discourse operated a displacement of ‘the South’ into the Aegean, as the Dodecanese became Italy's imperial limes where civilisation faded out into the exotic and Europe blended with the Levant, or ‘the Orient’. This in turn could enable a better absorption of the Mezzogiorno into the national community.Footnote 28

In the 1920s, these theoretical considerations served well political leaders who attempted to redefine Italy's regional role in the Eastern Mediterranean following the upheavals of the First World War and the Greco-Turkish War. Hence Orazio Pedrazzi, an ambitious journalist and staunch supporter of the fascist regime who would have a glowing career as a Member of Parliament and diplomat, wrote:

The people [popolazioni, in reference to the Orthodox, Muslim and Jewish communities] of the Dodecanese are not people of colour. They do not need to be civilized, they only need to be assisted. If we were to turn the islands into a colony [colonia] we would profoundly offend the inhabitants and above all we would pervert the nature of the dependency [possedimento] . . . Libya can be an end in and of itself. The Dodecanese cannot be an end in itself . . . The Dodecanese . . . should serve our economic, cultural and political expansion in the Levant, it will be . . . a beacon of culture, a sanctuary for all [Italian] migratory colonies in the East.Footnote 29

The representation of Dodecanesians as not being ‘people of colour’, and the project of using the archipelago as a base for the exercise of what we would today call soft power in the ‘Levant’, followed the collapse of Italian dreams of territorial expansion in Anatolia with the rise of the Turkish nationalist movement. Not able to annex Anatolian territory, Italy fell back on a well-proven policy examined by Mark Choate and Joseph Viscomi consisting in influencing the numerous Eastern Mediterranean ‘Italian’ or ‘Franco-Levantine’ communities, which were also, tellingly, referred to as colonies (colonie).Footnote 30 Italianity (Italianità), the alleged cultural link between these colonie and the metropole, allowed the latter to project imperial claims far beyond the territory under its direct sovereignty. This context would also increase the geopolitical importance of the Dodecanese within the Italian Empire and turn mere perceptions about its inhabitants into a policy, which went even further than what the British had done in Cyprus.

On the one hand, the Italian regime in the Dodecanese, even before the advent of fascism, was, by any measure, repressive. Elections, at the village and municipal levels, were swiftly abolished and power was centralised in the hands of the ‘Governatore’. In addition and somewhat contradicting Pedrazzi's statement to the effect that the Dodecanese was not a ‘colony’, Italian authorities, perhaps replicating the policy, so thoroughly studied by Roberta Pergher, they had implemented after the First World War in Trieste and the Trentino and in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, used settler colonialism to consolidate their sovereignty on the archipelago, a process that implied large-scale expropriations.Footnote 31 On the other hand, however, by an October 1925 decree-law, they devised an Aegean citizenship (cittadinanza egea) for the Dodecanesians, which safeguarded their customary rights and placed them at the helm of the Italian colonial hierarchy.Footnote 32 In 1933, Italian authorities facilitated the access of Dodecanesians to the full, metropolitan Italian citizenship. Comparable experimentations in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica had been part of a tactical, and short-lived, attempt to reduce local resistance.Footnote 33 Nothing like the cittadinanza egea existed elsewhere in the Italian Empire.Footnote 34 Filippo Espinoza convincingly argues that in creating it, Italian authorities had imitated the institution devised by their French rivals for the inhabitants of Kastellorizo (Castelrosso), one of the Dodecanesian islands they briefly occupied before ceding it to Italy (1915–21).Footnote 35 Davide Rodogno sees in this ‘citizenship’ a sign of deference on the part of Italian authorities for a population they considered culturally proximate.Footnote 36 However that may be, observers of the time were quick to understand the practical implications of this citizenship. Vittorio Alhadeff, a prominent lawyer and a scion of one of the wealthiest Rodesli (Rhodian Jewish) families, thus wrote that the October 1925 decree ‘demonstrated that Italy thereafter considered anything related to the islands and their inhabitants as a matter of pure domestic law’.Footnote 37 It had the additional benefit, of course, to clarify the jurisdictional ambiguity mentioned in the first section of this article.

Ann Laura Stoler writes that all imperial formations have always relied on ‘scaled genres of rule that produce and count on different degrees of sovereignty and gradations of rights’.Footnote 38 And, as scholars of legal pluralism have noted, differences in the institutions and administrative practices from colony to colony often reflected the conditions in which a territory and its inhabitants had been brought into the fold of empire.Footnote 39 Colonial perceptions of the local populations were also, as this section aimed to suggest, decisive in justifying a certain method of rule and in the creation of specific legal instruments to serve that purpose. Interestingly, on the basis of comparable representations of their Eastern Mediterranean subjects, the United Kingdom and Italy designed vastly different institutions. As mentioned earlier, however, by the mid-1920s, British authorities were considering Italian methods as more efficient in ruling Dodecanesians than theirs had been with Cypriots. Gradually in the 1920s and more decisively so in the 1930s, they simply duplicated a number of their Italian counterparts’ policies.

The Italian Dodecanese as Administrative Toolbox for British Cyprus

For reasons that will be addressed in the last section of this paper, British colonial authorities remained entirely oblivious to the Italian claims of a shared cultural identity with their Eastern Mediterranean subjects. What interested them was what they perceived as an efficient combination between political authoritarianism and economic development lying at the core of Italian rule. Renowned British archaeologist Stanley Casson reckoned, in a 1936 article published in the prestigious Fortnightly Review, that the thousands of tourists who visited Cyprus after having seen Rhodes would probably feel quite unimpressed by the British administration's utter neglect of both people and monumental sites which contrasted with Italy's meticulous care for the Dodecanese.Footnote 40 In 1939, former Governor of Cyprus, Sir Richmond Palmer, stated, in a lecture he gave at the Royal Central Asian Society:

When other Mediterranean Powers spend freely on development and other port facilities in their Mediterranean possessions, such as Tripoli and Rhodes, Cypriots are apt to think that there must be something wrong with Great Britain if she cannot do the same for Cyprus after all these years, especially in view of the fact that Cyprus is a much more fecund field for development than either Tripoli or Rhodes.Footnote 41

As already mentioned, this acknowledgement partly owed to the belief that the Italians had found a permanent solution to Greek irredentism, seemingly earning the acquiescence of their subjects through a combination of repression and welfare. In the late 1920s, Governor Storrs attempted to implement a few Italian-inspired measures. One of them was the 1928 law on pious foundations (Evkaf), which brought the latter, as the most influential institution of the Muslim community, under government control. Another one, was the 1929 education law, inspired by a similar 1926 Italian law, which divested Orthodox and Muslim education boards of their control over elementary schoolteachers, who thus became government employees. The 1929 education law radicalised the Greek-Orthodox opposition to British rule and contributed to Storrs's undoing. In October 1931, a year marked by economic crisis and a protracted tension between the governor and the legislative council, an island-wide revolt in the name of enosis culminated with the burning down of Government House.Footnote 42 No doubt this was humiliating but more cynical observers in the Colonial Office likened it to a ‘godsend’ that would justify the abolition of all of the island's representative institutions, from the legislative council – an ‘exasperating and humiliating nuisance’ according to Storrs – to the municipal and village councils, which British authorities felt had stood in the way of their ‘benevolent rule’.Footnote 43 If the regime they had established in 1882 in Cyprus was among the most liberal in all of their possessions, the one that took shape after 1931 was arguably the most authoritarian.

In the 1930s, British colonial authorities in Cyprus more clearly aligned their policy on that of their Italian counterparts in the Dodecanese. The broader context behind this convergence was the global economic crisis following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the widespread belief in European political and administrative circles that authoritarian regimes, communist and fascist, had more efficiently weathered the storm. As fascist or quasi-fascist organisations were mushrooming across Europe including in the continent's largest democracies, the mainstream elite, even when democratic at heart, believed they could borrow a leaf or two from the fascist book.Footnote 44 In 1937, right on the heels of the Abyssinian crisis, fifteen Conservative Members of Parliament created an Anglo-Italian Parliamentary Committee, meant to revive relations of trust between the two countries and also study fascist governance.Footnote 45 One of the most influential British administrators of the time, Secretary to the Imperial Cabinet Sir Maurice Hankey, thus wrote, upon returning from Italy, in glowing terms about the achievements of fascism in that country: ‘What Garibaldi and Cavour began, Mussolini had completed’. In the fascist experiment ‘the nation had found itself’.Footnote 46 This quote highlights both the strength but also the limitations of the appeal of fascism as a regime suitable not to the United Kingdom itself, but rather to unruly Mediterranean societies – Italy included. What seemed transposable to these settings was the high degree of executive authority fascists enjoyed, which enabled them to fast-track, without time lost in fruitless deliberations, reforms ultimately considered necessary and beneficial to the community.Footnote 47 This, incidentally, tied in well, from a conceptual perspective, with the post-First World War understanding of imperial rule as trusteeship and the prevalence of mise en valeur, the notion, that is, that European domination could no longer satisfy itself with the preservation of law and order but should also be, perhaps mainly, about promoting economic ‘development’ in the societies under colonial control.Footnote 48

It is noteworthy that this interest in fascist methods of imperial rule increased at a time when Anglo-Italian diplomatic relations were deteriorating rapidly.Footnote 49 In the wake of the invasion of Ethiopia, the declaration of the Italian Empire (impero italiano) in 1936 and the League of Nations’ sanctions, Italy drew closer to Hitler's Germany.Footnote 50 Mobilising a discourse full of references to the Roman mare nostrum and to Italy's Mediterranean destiny, the fascist government undertook to challenge French and British positions throughout the Middle Sea.Footnote 51 In the 1930s, British authorities confronted anti-colonial resistance in practically all of their Mediterranean possessions and almost everywhere Italian interference was easily perceptible. Fascist agents were fanning the flames of resistance in Egypt, Malta and Palestine during the Great Arab Revolt (1936–9).Footnote 52 In 1936, fascist authorities undertook the transformation of the Dodecanesian island of Leros into a fortified military base, inducing the British to briefly consider doing the same with Cyprus.Footnote 53 Even though the United Kingdom and Italy signed the Gentleman's Agreement in 1937 and the Easter Accord in 1938, the British Foreign Office decreed, somewhat perplexingly, that Italy ‘cannot be counted on as a reliable friend but in the present circumstances need not be regarded as a probable enemy’.Footnote 54 In these circumstances, British intelligence-gathering concerning Italian administrative methods could not take the overt, public and even cordial form they had in the 1920s. The British consul in Rhodes and the Italian consul in Nicosia, who were in the 1930s recruited from the intelligence services, provided much information, although they were placed under the surveillance of the local police.Footnote 55 More interestingly, perhaps, is the fact that despite official displays of hostility, active relations between British and Italian colonial authorities were maintained, albeit at the infra-state level, as the following example will show.

Most of the measures implemented in the 1930s by the British in Cyprus bear the stamp of Italian administrative methods, to the extent that a bureaucrat at the Colonial Office opined that ‘the Government of Cyprus are becoming imbued with the political philosophy of Mussolini’.Footnote 56 Laws were thus passed in 1933 and 1935 bringing the content of primary and secondary school education under administrative control. The press was subjected to sweeping censorship. Finally, taking their cue from their Italian counterparts, the British began interfering in the affairs of the Cypriot Orthodox Church, arguably one of the most powerful, socially influential institutions in the island.Footnote 57 Yet when the deteriorating economic situation and the resulting labour mobilisation appeared threatening to the status quo, both in metropoles and colonies,Footnote 58 the one aspect that attracted European bureaucrats to fascism was corporatism. This presented itself as a third way between capitalism and communism and was premised on the notion that society constituted an organic whole. Harmony between the different social classes would be ensured through corporations, in which representatives of both employers and workers would be brought together. Faced with the exponential growth of organised labour in Cyprus, British officials sought ways to solve the problem at its root, namely by slowing down the proletarianisation of the landless peasantry. In 1934, Brewster Joseph Surridge, then district commissioner of the Cypriot district of Larnaca, undertook at his own expense a trip to Italy with the intention of meeting officials of the Ente Nazionale Fascista delle Corporazioni, the organism overseeing all twenty-one corporations in Italy. The British official was allegedly so impressed by what he saw that upon his return to the island he pleaded with the governor for, and was granted, the responsibility to develop cooperative societies in Cyprus on the Italian model. Four years later, in 1938, Surridge decided to undertake a new trip to Italy, this time sponsored by the Cyprus administration, with a view of studying corporatism as applied to the fishing industry.Footnote 59

Naturally, according to the Italian consul, such a visit could make of Surridge ‘an increasingly useful element to serve our propaganda among Cyprus's government officials who until now are, in their great majority, animated by hostile feelings towards fascist Italy’.Footnote 60 It has been argued that as a late-coming and therefore insecure imperial power, Italy often compared its colonial policy-making to that of its rivals; its imperialism, it is said, was ‘largely imitative’.Footnote 61 Yet as the examples examined here suggest, Italian authorities were simultaneously aware of the appeal of their imperial model and consistently contrasted their supposedly respectful and beneficial rule to that, allegedly neglectful, of their French and British rivals.Footnote 62 In the early 1930s, diasporic Dodecanesian and Greek Cypriot newspapers took notice but disparaged this appeal of the Italian model. ‘[W]e insist’, read an article published in Dodekanisiaki, the Athens-based organ of the Dodecanesian youth, ‘in believing that British policy in Cyprus has been, since the First World War, a true copy of Italian administrative methods in the Dodecanese’.Footnote 63

This was, however, an exaggeration. While the decisive influence of Italian methods over British policy in Cyprus is undeniable, this was not by any means a case of wholesale duplication. Rather, British colonial authorities treated the Italian administration of the Dodecanese as a toolbox, from which they could retrieve some useful ideas. A major hindrance in completely aligning their rule on that of their rivals was of an economic nature. In effect the irony was that mise en valeur gained credence in British colonial circles precisely at the time of the Great Depression, namely when ‘[f]unds for longer-term investment evaporated’.Footnote 64 As a result, in the 1930s British authorities implemented mostly institutional, as opposed to economic or financial, reforms in Cyprus, with rather dubious political dividends. By contrast, Italy deployed onerous construction works, lavishly using metropolitan funds, namely Italian taxpayer money, a source British officials were extremely reluctant to resort to.Footnote 65 More importantly, however, and as the following and final section aims to show, British authorities remained completely oblivious to the ideological underpinnings of fascist rule in the Dodecanese and specifically their mobilisation of a chronopolitics and a biopolitics clearly intended to achieve the assimilation of the islanders into the Italian national community.

Building a European Mediterranean Community: Fascist Chronopolitics and Biopolitics

In Cyprus, the October 1931 revolt brought about a major transformation in British official representations of the island's inhabitants. Whereas up until the 1920s British colonial officials would acknowledge the local population as ‘Greek’ and ‘Turkish’, such terms, again following the Italian example, were thoroughly purged from the official correspondence and replaced with ‘Orthodox’ and ‘Muslim’ respectively. Cypriots were more broadly equated to other Mediterranean populations of an ‘Asiatic’ or ‘Oriental’ rather than ‘European’ stock.Footnote 66 In 1936, reflecting on the resistance British imperial rule met in Malta, Cyprus and Palestine, Sir Arthur Dawe, head of the Pacific and Mediterranean department at the Colonial Office, thus wrote of the local populations:

The people are excessively addicted to scandal and intrigue. They are always ready to throb with hysteria about petty politics and in the political sphere are much more destructive than constructive. The Romans before us found them a stiff-necked, hot-headed lot, subtle and difficult to govern.Footnote 67

This representation of Mediterranean populations as intellectually sophisticated but unruly formed part of an old and tried repertoire. As shown by Thomas W. Gallant and Sakis Gekas, British officials had already resorted to it when they tried to counter the lively movement for enosis in the Ionian Islands during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 68 What is certain is that Mediterraneanness functioned – similarly to Orientalism – as an otherising device for British officials, one justifying the exercise of colonial rule.Footnote 69 This was not lost on Cypriots who, brazenly breaking solidarity with other colonial peoples, openly protested against being treated like ‘the nomads of Oceania’.Footnote 70 It was also exploited by Italian authorities,who, opposed to their British counterparts, referred to Mediterraneanness (mediterraneità) in positive terms. ‘In fact, the English’, wrote the Italian consul in Nicosia in 1937:

have isolated themselves completely from the rest of the population and, as ‘superior beings’, have refused to maintain the least social contact with anyone who is not ‘British’ by birth and blood. Hence every lesser English civil servant – whose father may be a bartender in London – feels it his right and duty – once he arrives here – to show the most profound contempt even to noble Cypriot families, whose names go back to the Crusades or the Venetian domination.Footnote 71

Mediterraneità was a polysemic term in fascist Italy. It was a concept, as Claudio Fogu explains, rallying Italian artists and rationalist architects who sought to ‘distinguish themselves from their Northern European rivals and to fence off the increasingly worrisome accusations of esterofilia (love of everything foreign) levied against them by the ever more vocal proponents of an official fascist style responding to the idea of romanità (Romanity)’.Footnote 72 In official colonial discourse, McGuire argues, mediterraneità functioned as a chronotope designed to resolve two paradoxes besetting fascist ideology: the ambiguous relation between modernity and past, both of which were officially extolled; and the distance required by a colonial form of rule over a population with which, nonetheless, Italians claimed a familiarity.Footnote 73 More prosaically, it was, in Mussolini's increasingly martial declarations, a metaphor for fascism's imperial ambitions, comparable to that of the fourth shore (quarta sponda), when referring to Libya (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. ‘The Italian people is the only great people that is entirely Mediterranean'.

Source: ‘Messaggero di Rodi’, 20 June 1940.

In contrast to their British rivals then, the Italians used the Dodecanese to strategically dim, or blur, assumed cultural differences between themselves and Mediterranean societies in a bid to increase the appeal of their own imperial model of governance. Governor Mario Lago, in the preface he wrote for a 1930 guide book, thus stated that the ‘Orientals, who share with us so many affinities and for this reason are accessible to our civilization and our culture, need to be convinced that modern Italy [l'Italia d'oggi, i.e. fascist Italy] knows how to organize a country and generate wealth just like all the great Western powers’.Footnote 74 The Dodecanese, the smallest province of the Italian Empire, was attributed an immense propaganda value. It was ‘the sea-girt, insular jewel in the crown of an empire that was closely tied to the idea of the sea – and to the wealth and identity that the sea had historically brought with it’.Footnote 75

As the source from which Lago's citation is taken indicates, the one medium Italian authorities consistently used for propaganda purposes was tourism. From the beginning of their rule over the archipelago, Italian authorities had conducted extensive sanitary works, road building, the construction of flashy administrative buildings, which contrasted greatly with the paltry British record in that domain in Cyprus. The swiftness and efficiency with which the capital town of Kos was reconstructed after it had been severely damaged by the 1933 earthquake was an architectural feat.Footnote 76 As many Dodecanesians remember, such works considerably improved their living conditions.Footnote 77 Yet the most onerous constructions had been made to serve Italy's imperial interests, in their military and cultural form, and were therefore focused on the islands of Rhodes, Kos and Leros. The first two islands in particular were destined to become important touristic destinations for Europeans to experience the thrills of a domesticated Orient. The baths of Kallithea built by Pietro Lombardi perfectly embody this policy, borrowing as they did from Roman, Byzantine but also Ottoman architectural styles.Footnote 78

Beyond their touristic potential, the architectural styles with which Italian authorities experimented in the Dodecanese also reflected a shifting chronopolitics, a politics of time that is, meant to legitimate Italian rule in the Dodecanese both by invoking (rather than evoking) the past and by emphasising the vitality of Italian rule in the present. Recently, among a number of scholars, Dan Edelstein, Stefanos Geroulanos and Natasha Wheatley have underscored the tight connection between power and time, and the fact that ‘[p]olitical reorganization . . . can be understood as temporal reorganization’. Most exemplary of the ‘co-constitution of [the] temporal and political orders’ in the Dodecanese was the Palazzo del Governatore – the Governor's residence and offices – designed by Florestano di Fausto and built in 1926–7 in front of Rhodes's main harbour, close to the medieval town.Footnote 79 This combined rationalism and modernism with decorative elements meant to evoke Islamic architecture, and, through this, Italy's destiny in the Orient. The clearest reference, however, was to the Palazzo Ducale in Venice, as it signified Italy's return as a ‘thalassocracy’ or a maritime empire.Footnote 80 By contrast, Cyprus's government house, built on the ashes of the one burnt during the October 1931 uprising, was imposing, but its blend of references to local architecture and English Gothic had nothing of the Palazzo del Governatore's symbolic power.

This hypostatisation, rather than commemoration, of a carefully selected past, was perceptible in monument restoration as well. Of the numerous monuments left by the archipelago's successive overlords, Italian archaeologists of the Istituto Storico Archeologico (FERT) prioritised research on, and restoration of, the ones that allegedly proved the uninterrupted involvement of ‘Italians’ in the Levant, from the Romans to the seaborne empires of Venice and Genoa through the Knights Hospitaller.Footnote 81 Representative of this was the restoration in 1937–40, by Vittorio Mesturino, of the Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes, where Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi, Lago's successor, had chosen to relocate his headquarters. Scholars have underscored how creative this ‘restoration’ had been, based on an irreverent conflation of time, as Roman vestiges were brought in to decorate a Gothic medieval structure.Footnote 82 But this was in character with fascist chronopolitics as it had been practised around the Italian sovereign space. It illustrated, as numerous scholars have shown, a very Nietzschean, monumentalist, perception of the use of history. ‘The past’, write Esposito and Reichardt, ‘became a malleable material at one's disposal to use for the present’.Footnote 83 The purpose of this archaeological activity and of the style used in fascist architecture in the Dodecanese was to produce a ‘rupture in time, breaking through historical strata to establish an unmediated, simultaneous experience of Roman [and other glorious stages of ‘Italian’] past and fascist present (and future)’.Footnote 84 Fascist chronopolitics then, was premised on a rejection of ‘clock time’, the idea of time as linear and progressive, and embraced instead a concept of simultaneity between fascist modernity and selected, illustrious, moments of the past.Footnote 85

Reflected in the handling of the built environment, this chronopolitics was also perceptible in official representations of the local population. According to the writers of the previously mentioned guide prefaced by Governor Lago, the very language spoken by Dodecanesians was a medium actualising the past within the present:

As far as the vocabulary is concerned the most striking feature is the abundance of sounds of Italian origin or taken from Italic dialects, profuse in the entire Eastern Mediterranean, but especially in these islands where the successive rule of the Genoans, the Venetians, the Knights were longer-lasting, and where one can still find Italian banks and warehouses and where the Italian merchant navy dominated unrivalled for a long time.Footnote 86

The local population were therefore themselves vestiges of an immediately invokable, actualisable past, one that, again, unearthed a transtemporal, palingenetic connection between the ‘Italian’ Dodecanese of the past and the fascist Italy of the future. It is therefore somewhat seamlessly that such representations of Dodecanesians in turn became the ground for the gradual development of a biopolitics specific to the archipelago, and which aimed at assimilating the islanders. Just like time, they became the material to actualise the new fascist men.Footnote 87 Again, nothing remotely similar existed in British Cyprus. Mention has already been made of the cittadinanza egea, the sui generis citizenship granted to the inhabitants of the archipelago in the name of their alleged ‘whiteness’. By the mid-1930s, much more decisive steps were taken in the direction of ‘Italianising’ the local Greek-Orthodox population and one medium used – aside from strong incentives to join fascist organisations or the imposition of Italian as the sole language of education – was mixed marriages, namely unions between Italian officials and Dodecanesian women.

In Cyprus, mixed marriages were usually frowned upon and perceived as a threat to the colonial official's impartiality in a multicultural society inhabited by Orthodox-Christians, Muslims and other smaller denominational groups. Often it was the case that British officials who married locally were transferred to some other colony. Italian authorities in the Dodecanese seemed to have at first shared these concerns, especially given the fact that women who married Italian officials had to convert to Catholicism, which often created tensions with the local religious leaders and caused the bride to be ostracised. Such cautions were set aside, however, as it became apparent that the plans for settler colonialism had all but failed by the early 1930s.Footnote 88 The policy of biological assimilation of the Greek-Orthodox population into the Italian national community was pursued more earnestly as the impero italiano took a racialist turn in the 1930s, particularly in the wake of the conquest of Ethiopia.Footnote 89

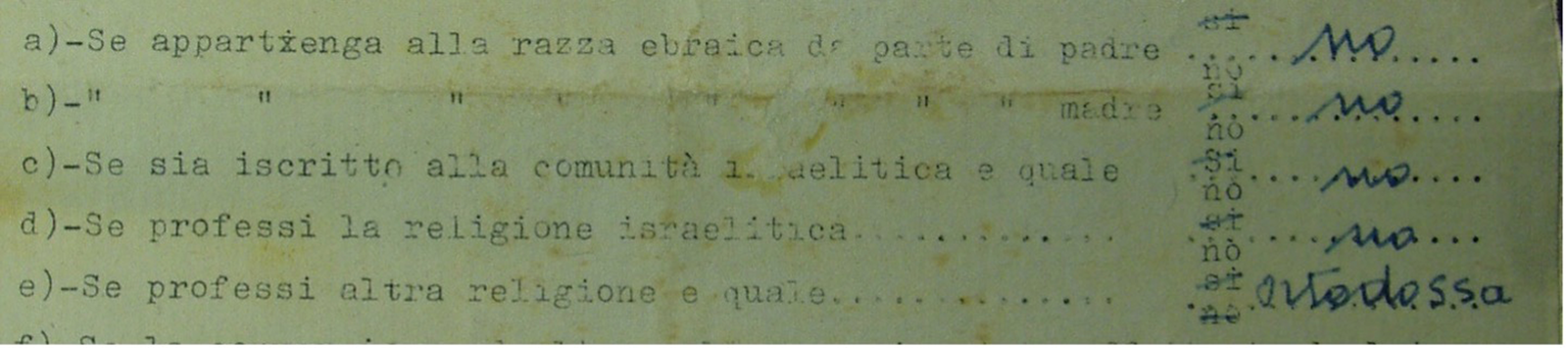

From the mid-1930s onwards, the official organ of the Italian administration in the Dodecanese, Messenger of Rhodes (Messaggero di Rodi), began running a series of anti-Semitic articles under the telling titles of ‘race’, ‘Semites’ and ‘Jews’.Footnote 90 There was, that newspaper claimed, a radical difference between ‘European Mediterranean people and oriental or African Mediterranean people’.Footnote 91 As Aliza Wong suggests in her work, biological racism had already a long pedigree in Italy by the 1930s. From the work of positivist criminologist Cesare Lombroso in the 1870s to that of his counterpart Alfredo Niceforo in the 1910s and 1920s, this division between ‘European Mediterranean people’ and ‘African Mediterranean people’ had specifically served scientific circles to ‘explain’ the perceived backwardness of the Italian South.Footnote 92 What changed in the late-1930s was that the government itself had embraced biological racism, in its Nordicist form, as advocated by the head of the Italian Racial Office, Guido Landra.Footnote 93 It began to inform Italian policy in its colonies, the Dodecanese included. Following the passing of the 1938 measures for the defence of the Italian race (provvedimenti per la difesa de la razza italiana), the small Jewish community of Rhodes was systematically discriminated against. Dodecanesian Jews were barred from practising certain occupations and were forbidden to engage in matrimonial union with non-Jews. In fact, before contracting a marriage, a member of any other Dodecanesian community, Muslim or Christian, had to obtain an official document from the authorities, certifying that they were not from ‘razza ebraica’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Extract of a certificate of non-Jewishness.

Source: GAK Undated ¼ extract of the certificate for Zappo Giorgio, enclosure into official government report, 21 Feb. 1939.

Indeed, a significant consequence of official anti-Semitism in the Dodecanese was that it cast all non-Jewish islanders into the ‘Aryan’ category, thus making them fully assimilable to Italy. It seems that in the Dodecanese, to paraphrase Roberta Pergher, Italian authorities had found a way to ‘square’ the fascist obsession with ‘national cohesion with rule of non-Italian lands and peoples’.Footnote 94 Such territories, once expurgated from the new official ‘other’, were to simply be nationalised. The Dodecanese was therefore to be considered as an integral part of Italy and no longer an imperial dependency. Nothing comparable had ever been contemplated for Cyprus.

Conclusion: At the Crossroads of two Mediterraneans

Following the injunction of scholarship on imperial formations to consider European colonial policy-making as an adaptable process, one that resulted from mutually constitutive influences between metropole and colony, nation and empire and across imperial borders, this article revealed a moment of convergence between the policies enacted by the British in Cyprus and the ones implemented by the Italians in the Dodecanese. One major impulse was the challenge of Greek irredentism shared by both colonial powers in their Eastern Mediterranean, insular dependencies. Another one was the recasting of imperial rule as trusteeship in the interwar years and the imperative of economic development this entailed in the context of the Great Depression. As a result, British authorities drew inspiration in their administration of Cyprus from Italian rule in the Dodecanese, specifically from what they perceived there as being a successful combination of political authoritarianism and public welfare. To a certain extent then, fascist authorities had been successful in using the archipelago to enhance Italy's credentials as an imperial power worth emulating.

Emulation is not, however, imitation, and the article also calls attention to the very substantive differences between the British and Italian imperial experimentations in the Eastern Mediterranean. British official correspondence started to invoke more regularly the Cypriots’ ‘Mediterraneanness’ in the 1930s, particularly after the 1931 uprising. But this notion was meant as an otherising rhetorical device, a synecdoche for a series of alleged cultural flaws – propensity for intrigue, restlessness, dishonesty – which Cypriots supposedly shared with other Mediterranean colonial subjects, such as the Maltese, the Arabs or the Jews and which justified the exercise of an Italian-inspired, authoritarian rule. By contrast Italian authorities had embraced mediterraneità, a polysemic term in official discourse, as a means to strategically blur the divide between rulers and ruled and convert the small Dodecanesian dependency into a beacon of Italian imperial influence throughout the Middle Sea and the ‘Orient’. The chronopolitics used in official discourse, architecture and archaeology for that purpose led, with the racialist turn of the 1930s, to a biopolitics aiming at the assimilation of Greek-Orthodox Dodecanesians into the Italian national community. Just as the United Kingdom sought to finally turn Cyprus into a British colony, Italy was seeking to nationalise the Dodecanese.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Patrick Berhnard and Fernando Esposito, for their encouragement and for reading early versions of this paper, as well as the three anonymous reviewers for their detailed and generous feedback.