From the Buddhist point of view, there are therefore two types of mechanisation which must be clearly distinguished: one that enhances a man's skill and power and one that turns the work of man over to a mechanical slave, leaving man in a position of having to serve the slave. How to tell the one from the other? ‘The craftsman himself’, says Ananda Coomaraswamy, a man equally competent to talk about the modern west and the ancient east, ‘can always, if allowed to, draw the delicate distinction between the machine and the tool. The carpet loom is a tool, a contrivance for holding warp threads at a stretch for the pile to be woven around them by the craftsmen's fingers; but the power loom is a machine, and its significance as a destroyer of culture lies in the fact that it does the essentially human part of the work'. (E. F. Schumacher, ‘Buddhist Economics’, in Small is Beautiful (1973), 50Footnote 1)

Introduction

E. F. Schumacher (1911–77) is best known as the author of the widely-read and influential book of 1973, Small is Beautiful: A Study of Economics as if People Mattered. Criticising the human and environmental failings of the modern economy and condemning the violence of its technologies, it became an iconic work for the environmental and countercultural movements of the 1970s. Its many ‘Green’ readers included decentralists, back-to-the-landers, proponents of voluntary simplicity and anti-nuclear activists.Footnote 2 Not surprisingly, the book outraged some economists, who felt that it undervalued the accomplishments of the modern economy, traded in emotional arguments and wilfully ignored economic reality.Footnote 3 Nonetheless, it made Schumacher a household name. Without it, he would likely have been remembered, if at all, as a peripheral figure in wartime Oxford economics, and a critic on the fringes of the English environmental movement of the 1960s.

Less well-known is the fact that Schumacher became a dissident economist while in the employ of the National Coal Board. He became a critic of industrial society and advocate of gentler technologies while mining a fossil fuel that was polluting in its extraction and consumption, and reliant on heavy technology and mechanisation. If he chose to promote the Gandhian renunciation of violence and the conservation of earthly resources, it was while working in a sector where men and machines irreparably churned up the earth, accidents were legion and industrial strife recurrent. If he championed the use of intermediate, or appropriate, technology in the so-called developing world, he did so while overseeing the heavy mechanisation of minework back in industrial Britain. How were these contrasting spheres of Schumacher's life related?

We answer this question by first providing a brief overview of Schumacher's varied life and then scrutinising his two decades at the coal board. In the first decade, the 1950s, he began to look askance at the modern, Western world. Precisely while becoming an industrial economist, he began to explore Gurdjieff-Ouspensky, Buddhism, yoga and related interests. This quest carried him to Burma in early 1955, where he wrote the foundation of his later, famous, essay, ‘Buddhist Economics’, which criticised the effect of modern economic development on traditional cultures. Returning to Britain, he became increasingly cognisant of what he called his ‘double-life’. On the one hand, he had to function as an economist of the mines, where he faced industrial strife; the obsession with rationalisation and efficiency; and the machinations of the impersonal, large-scale, modern economy. On the other hand, he was privately grappling for a sense of direction, reading further in philosophy and religion, and feeling increasingly alienated from much of what the coal board represented.

In the 1960s, he juggled to manage these two spheres. At work, he was increasingly called upon to defend coal production and help the company improve efficiency, through pit closures, rationalisation and mechanisation, while privately, as a result of visits to India and his reading of Gandhian and Traditionalist authors, he became critical of the use of advanced technology in overseas development. By the middle of the decade, caught between the demands of ‘coal’ and the pull of the ‘East’, he was apparently ready to quit the coal board. Yet, he stuck it out for another five years, on the one hand defending coal, on the other promoting Intermediate Technology abroad and turning out article upon personal article critical of the modern industrial world. Coherence came when he could finally retire from the coal board, devote himself to development, and, gathering his ideas together, write his book.

A Curious Path to Accidental Renown

The son of Berlin economics mandarin Hermann Schumacher (1868–1952) and nephew of the well-known Munich architect Fritz Schumacher (1869–1947), he studied economics and politics, first in Germany and then at New College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar.Footnote 4 In 1934, following two years at Columbia University, as research student and lecturer in monetary economics, he returned to Germany. There, with a brother-in-law and some friends, he became involved in a private trading business, one of the effects of which was ostensibly to enable German businessmen, many of them Jewish, to remove their money from Germany. More critical of the Nazi regime than some of his family, Schumacher left the country in 1937, moving to London, where he continued in the same business and then worked in the City until the outbreak of the Second World War.Footnote 5

The conflict marked a serious setback for him, his German wife and their two young sons. Now an enemy alien, he spent a short period in detention at Prees Heath internment camp in August 1940, but was then able to spend the rest of his confinement, along with his family, as a farm-labourer in Northamptonshire. This was made possible by ‘connections’: the first being David Astor (1912–2001), scion of the eponymous family and later editor of The Observer, whom Schumacher had known since his Oxford days; and the second being Astor's uncle, Robert Brand (1878–1963), erstwhile Lazard Bros. banker and Treasury civil servant, whom Schumacher had come to know while in the City. It was on Brand's country estate, Eydon Hall, that he became a farm-worker.

Brand was already reading essays by Schumacher on the Nazi economy before the latter's confinement. Along with Lord and Nancy Astor, Philip Kerr (Lord Lothian) and Geoffrey Dawson (The Times), he was part of the ‘Cliveden Set’, later to be accused of seeking to appease Hitler in the pre-war years.Footnote 6 Apparently the least conciliatory of this group, Brand sought Schumacher's opinions and continued to encourage his writing, not only on the German economy, but also on eventual postwar international arrangements. After June 1940, at the cottage at Eydon, cut off from any German family support, struggling on a farm-labourer's wage and keen to exert some influence, Schumacher continued to write.

One such article, on the prospective postwar reorganisation of the international-payments clearing-system, was brought by Brand to the attention of J. M. Keynes, whom he had know since at least the Paris Conference of 1919, when both were present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.Footnote 7 Keynes’ interest in that paper gave rise to a difficult journey by Schumacher from Eydon to Bloomsbury in December 1941, where, struggling past the piles of books in the narrow hallway of the great man's home, he met with him and engaged him in an afternoon's lively discussion.Footnote 8 While it remains unclear whether Schumacher's detailed ideas on multilateral clearing were of significant influence upon the Keynes Plan for postwar financial reconstruction, the effect was to increase his visibility in Oxbridge circles. He was soon taken on as a research economist at the Oxford Institute of Statistics, working under Polish émigré Michal Kaleçki – Keynes’ brilliant precursor – and alongside other exiles such as Hungarian Thomas Balogh and Germans Fritz Burckhardt and Kurt Mandelbaum (later Martin). Although Schumacher's conversion to socialism had been recent, he integrated quickly into what was regarded at Oxford as a nest of Continental Reds.

There he wrote papers about wartime economic organisation and also became deeply involved in William Beveridge's creation of the postwar welfare state. Along with Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor and David Worswick, he was one of the ghost-writers of Beveridge's (1944) Full Employment in a Free Society, and was involved also with the BBC's public introduction of that vast project.Footnote 9 It is worth noting, however, that, as a German, Schumacher was excluded from direct contact with the broad public, and that Beveridge's collaboration with this ‘totalitarian Prussian’ was later used by his critics in attempts to discredit him.Footnote 10

In 1945, Schumacher returned to Germany for the first time since 1937, in order to participate in the Strategic Bombing Survey, under the direction of J. K. Galbraith, and alongside Kaldor and Tibor Scitovsky, Hungarian émigrés both.Footnote 11 His letters at this time show that the confrontation with the devastation was traumatic for him.Footnote 12 In addition, the war had cost the life of his younger brother, Ernst, who had progressed from the Hitler Youth to the Wehrmacht and died in 1941 on the Russian Front, and was viewed as a hero by their father. There was also the complication surrounding the loyalties of Schumacher's brother-in-law, Werner Heisenberg, who had married Schumacher's younger sister, Elisabeth, in 1937 and had chosen to remain in Germany during the war, working on atomic research. When Schumacher was returning to Germany in 1945, Heisenberg, along with a dozen other physicist colleagues, was being spirited in the opposite direction, to England. There they would spend six months as guests of Her Majesty's Government at a stately home, Farm Hall, under ‘bugged’ surveillance, in order to determine what they knew about the potential creation of a German nuclear bomb. Their listeners were helped by their reaction, in August 1945, to the news that the Americans had dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While the episode has been covered in detail by historians of physics, there remained hanging over Heisenberg a shadow sufficiently large for his wife to write a book some forty years later defending his reputation.Footnote 13 As a practitioner of science and promoter of nuclear energy, both of which Schumacher would become increasingly critical of, Heisenberg would become an important, if unspoken, presence in the life of his Anglo-German brother-in-law. In 1946, Schumacher returned again to Germany, for four years this time, as an economist with the British section of the Allied Control Commission. Once again, questions of identity and loyalty loom large. He was now a German-speaking English subject, wearing a British uniform, involved in de-Nazification and postwar reconstruction.

In late 1949, he accepted a post as economic advisor with the recently created National Coal Board in London, and began work the following year. Although he was glad to leave Germany, his wife was less so. Attached to her family, a prosperous, commercial dynasty in Reinbek, near Hamburg, Anna Maria Petersen had to be dragged back to dreary England.Footnote 14 Frequently thereafter, she would rejoin her parents in Germany or on holidays abroad, and the conflicting pulls of England and Germany were an issue for the couple until her untimely death in 1960. Schumacher remained at the National Coal Board until 1970, when he retired, at fifty-nine, by which time he was devoting himself heart and soul to the promotion of Intermediate Technology in developing countries. In 1973 he pulled together various of his essays on development, technology and the modern world, and finally persuaded the small publisher Anthony Blond to take on the manuscript.

With its catchy title, Small is Beautiful found a ready readership, especially in North America, and Schumacher found himself in the limelight. The book was widely reviewed and he was solicited to give a great many public talks. This he did for a solid four years, arguably pushing himself too hard, until he died of a heart attack on a Swiss train, travelling to yet another engagement. The year of his death saw the publication of his A Guide for the Perplexed, which has been read by relatively few but was apparently more important to him than his best-seller.

The 1950s: The Fissure Appears

Among the notable features of Schumacher's personality were, firstly, his ability to change his mind and, secondly, the eloquent vigour with which he would defend his latest beliefs and opinions. While such a change frames his entire adult career – from the early, leftish Keynesian, and believer in modern progress, to the later critic of growth and modernity (and Keynesian morality) – there were also smaller ‘epiphanies’ along the way. For example, during the war, for several years under the influence of Nietzsche, he was ardently anti-religious, writing withering letters to close Christian friends, such as his former business colleague and fellow exile, Werner Simson.Footnote 15 Yet, by the early 1950s, he was on the way to becoming a religious man himself. Or in politics, where, to judge by his correspondence, his conversion from liberalism to socialism was abrupt, triggered by the several weeks spent in Prees Heath internment camp in August 1940, in the company of fellow detainee and expatriate Kurt Naumann and sustained by readings Naumann sent to him on the farm, viz., Lenin, Engels, Bernal and others. When Schumacher arrived at Oxford in 1943 to work with Kaleçki, one would never have guessed at the recency of his conversion.Footnote 16

He was similarly enthusiastic about his passion for gardening in the early 1950s. In spring and summer, before boarding the morning commuter train at Caterham, Surrey, he had often put in a good hour's work in the garden – soon described as his ‘church’ – applying the horticultural principles learned from the literature of the Soil Association.Footnote 17 Not only did he read the organisation's manifesto, The Living Soil, by Eve Balfour, and related works by Lord Northbourne, George Stapledon, Albert Howard, Robert McCarrison and Guy T. Wrench, but he became a member himself and would eventually become the association's president. Aboard the train, Schumacher used his time efficiently for reading, whether for work or in the literatures of Gurdjieff, Ouspensky and the Fourth Way, or Buddhism and other forms of Eastern spirituality. Alighting at Victoria Station, with tightly-rolled umbrella and Homburg hat,Footnote 18 the economist would proceed to Hobart House, headquarters of the NCB, with its staff of 3000. At the office he shared his gardening interests with colleagues, and even arranged a showing there of the Soil Association's promotional film.

With his esoteric interests, by contrast, he showed great discretion. At the coal board, his involvement in the Gurdjieff-Ouspensky teachings was known to only one colleague, Sam Essame, a fellow participant at the Gurdjeffian gatherings of John G. Bennett, scientific worker with the British Coal Utilisation Research Council and owner of Coombe Springs, an imposing home on the Thames in Richmond.Footnote 19 The central idea of Gurdjieff, and his Russian disciple P. D. Ouspensky, apparently distilled from traditional tribal teachings in northeastern India, was that modern man was not ‘awake’. A victim of routine, become machine-like, he was scarcely aware of what he was doing or thinking, and not realising his potential to achieve higher consciousness. This was possible under the guidance of a spiritual leader, through various exercises designed to bring about self-awareness. Alternation between the body and the mind was central to ‘The Work’, as the practice was called. Thus Gurdjieffians were trained to execute the ‘movements’, difficult dance sequences performed to the piano music of Thomas de Hartmann, or to engage in ‘conscious labour and intentional suffering’ in the garden. Whether at Gurdjieff's pre-war Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man near Fontainebleau, or Bennett's Coombe Springs in the 1950s, followers carried out backbreaking labour – digging holes, sawing lumber, clearing ground. Dancing or working, they faced occasional surprise interruptions by the leader who would ask them to ‘Stop!’, i.e. freeze in position, and focus temporarily on a particular thought.Footnote 20 The other Work teacher important to Schumacher was Maurice Nicoll, the Harley Street surgeon-turned-follower. In addition to organising discussion groups, Nicoll wrote several books reinterpreting the Christian Gospels along Gurdjieffian lines, including The New Man (1953), which Schumacher and his mother translated and had published in German.

It was also in the early 1950s that Schumacher joined the London Buddhist Society, where he attended talks and lectures and grew to know fellow expatriate Edward Conze (1904–79).Footnote 21 A Marxist scholar-turned-Buddhist translator, Conze became an important figure for Schumacher throughout the 1950s, introducing him to the Buddhist literature and providing courses on comparative religion. Although it is unclear whether Schumacher began to practise Buddhist meditation before going to Burma, he did take up yoga, and he would attribute the ease with which he settled in at Rangoon to his daily exercise routine.Footnote 22

Thus the figure of the labouring body resurges variously in Schumacher's life throughout these years. During the war, as a neophyte farm-worker in Eydon, on a largely non-mechanised farm with horse-drawn implements, the German mandarin's son discovered the meaning of back-breaking work. A tall, thin figure, evidently unused to labour, he had a tough initiation, facing the derision of the local fellows.Footnote 23 Then, there was the cultivation of the soil in his own garden at Caterham, where work was taking on a holy quality. Parallel with this, the world of Gurdjieff, where the body was punished in order to waken the spirit. And then yoga.

If Schumacher was able to embark on this private quest, and soon get away to Burma, it was because, in addition to being efficient in his use of time, he was under little pressure from his coal board employer. Indeed, in the early 1950s, his letters to his wife imply that he was feeling neglected – hoping, as always, for some real influence, but not quite achieving it yet.Footnote 24

He spent the first three months of 1955 in Burma as an economic consultant to the UN, evaluating the country's plan for economic and social development. The latter had been prepared by external American consultants: the New York engineering firm, Kappen, Tippetts, Abbet, McCarthy, and Washington DC economists Nathan Associates. By 1954, they had prepared a massively-detailed programme involving coal extraction; the construction of dams and irrigation projects; electricity generation (coal and water); and industrial development involving minerals, forestry, manufacturing and small-scale industry.Footnote 25 Agriculture was to be industrialised and intensified; logging and fishing were to increase; and the whole was to be facilitated by the overhaul of the rail system and the development of an elaborate road network. Working in close contact with the US State Department, the consultants emphasised the need not only to confront communist insurgency but also to transform the work habits of the Burmese – encouraging them to work harder in order to expand production and consumption.

Those ninety days in Rangoon were a watershed for Schumacher. As a pilgrim, he used his stay to the fullest: attending the historic sixth Therevada Buddhist Congress then taking place in the city, spending weekends learning Vipassana meditation with master U Ba Khin, discovering this Buddhist society with the help of several German expatriates then in the country.Footnote 26 While he acquitted himself with restraint in his professional evaluation of the Burmese development plan, he was privately horrified by what it seemed to imply for the society. His response was to write ‘Economics in a Buddhist Country’, which condemned not only the plan, for its likely corrosion of Buddhist culture, but the economics discipline itself, as a product of nineteenth-century Western materialism, neglectful of questions of ‘meaning and purpose’.Footnote 27 Just as one kind of economics was appropriate for a materialist culture, he claimed, so, too, was another appropriate for Buddhist or other societies. If Burma hoped to maintain a traditional ethic of non-violence and restraint, with the satisfaction of limited consumption through a minimum of means, then it was wrong to embrace the Trojan Horse of modern development.

In that paper, Schumacher also said what he truly believed about nuclear energy – his brother-in-law's field. Because of its creation of deadly waste, it was a ‘violent attempt to escape fate’, and to attempt to develop it on the scale necessary to replace coal and oil raised a prospect ‘even more appalling than the Atomic or Hydrogen bomb’. Needless to say, in the following years, when it came to dealing with nuclear power in the context of his coal board work, Schumacher was unable to reveal these true feelings, lest it be construed as special pleading on behalf of coal.

Returning to England and the coal board, he was now in a strange position. On the one hand, he was at the heart of an activity that was in many ways the epitome of Western materialist, industrialist culture: the extraction of a non-renewable resource, the combustion of which had enabled Western economic growth. On the other hand, as a result of his reading and his exposure to ‘economics in a Buddhist country’, he was calling into question the very process of economic development and the economics that underlay it. Living with this ‘double-ness’ would require compartmentalisation on his part.

Judging by his company writings, Schumacher's relative isolation at the coal board began to end around 1957. That year, he presented the ‘modern and efficient coal-mining industry’ to a banking audience, emphasising the company's progress with the adoption of power-loading and other kinds of mechanisation.Footnote 28 Although work stoppages continued to be a problem with a fifth of the workforce, productivity continued to rise. Oil was making inroads, but the vulnerability of supply was a critical consideration, while nuclear power was confined to making a modest contribution to electricity generation. After the skill of her people and the fertility of her soil, he said, coal remained ‘Britain's greatest asset’ (p. 5). That same year, at a conference devoted to ‘large coal’, he advised the coal board to raise the production of coal so as to be able to cease importing it from the United States. Drawing on production statistics, he went into considerable detail on the possible reduction of coal-piece size using explosives at the face and power-loading.Footnote 29

The following year, at a Federation of British Industry conference on nuclear energy, he introduced themes that would remain prominent in his coal board work thereafter. Given continued economic growth in the West, the industrialisation of the ‘undeveloped countries’ and prospective population growth, supplies of coal, oil and natural gas would soon prove inadequate, and nuclear energy was unable to fill the gap. By 1980, he said, total estimated oil reserves would last for another fifty years. Europe, by dint of its complete reliance on imported oil, was exposed to the dangers of a ‘fuel famine’.Footnote 30 Yet, he allowed himself to close on a philosophical note: ‘The fundamental problem of the Western European economy is and remains that of achieving stabilisation, of developing an economic system that will cease to worship a purely quantitative “standard of living” and foster, instead, the quality of life.’Footnote 31 At the NCB's Summer School at Oxford that year, he suggested that, despite the current recession, the prospects for coal remained strong. The company was raising productivity by closing down uneconomic collieries and reducing manpower. Further increases could be obtained through the ‘far-reaching rationalisation of underground layout by a policy of “concentration of workings in time and space”, and reducing wastage through fines (tiny coal pieces), so that ‘nothing that will burn is lost’.Footnote 32

While Schumacher wielded these economic arguments at Hobart House, the worm planted by Burma and private reading continued to grow. In an unpublished paper, likely written in late 1958, he wrote that economics, in its attempt to become more ‘scientific’, was losing touch with reality, becoming ‘lifeless and remote’.Footnote 33 In its concentration on ’appearance’ or ’form’, and its reduction of all phenomena to pure quantity, economics eliminated all considerations of meaning, and had become irresponsible. Price alone was not a ’reliable guide to responsible action’.Footnote 34 Non-renewable resources, such as coal, were fundamentally different from renewable primary materials. With coal, there was no production but, rather, the using up of capital. The policy of ’best seams first’ was a moral choice, implying the shifting of costs onto future generations. The government policy of colliery closure was based on their looking only to price and ignoring both vulnerability of oil supplies and likely future needs. There was an urgent necesssity for an economics of non-renewable primary goods.

The following February, in what appears to have been an unpublished talk to a Labour or socialist audience, he defended nationalised industry.Footnote 35 Private industry's narrow concentration on profits produced a ‘world made primitive by this process of abstraction or “reduction”’; one that ‘failed to do justice to the real needs of men’.Footnote 36 The Tory enemies of nationalisation were making public inroads with the corrosive suggestion that profitability was the only thing that mattered in public economic life. Schumacher disagreed: the purpose of a nationalised industry was ‘not simply to out-capitalise the capitalists . . . but to evolve a more democratic and dignified system of industrial administration, a more human employment of machinery, and a more intelligent utilisation of the fruits of human ingenuity and effort’.Footnote 37 That same year, following a parliamentary statement from Minister Reginald Maudling, suggesting the growing feasibility of nuclear power, a dissenting internal memorandum by Schumacher emphasised that Maudling's single favourable hypothetical outcome was made possible by the twin assumptions of low interest rates and that the competing conventional (coal-fired) plant was sited a considerable distance from the coal supply.Footnote 38

In a secret internal document in July of that year, he considered the NCB's plans for pit-closures in sixteen areas, mainly in Scotland, North England, around Durham, around Manchester and the Forest of Dean and Somerset.Footnote 39 Given the impossibility of transferring the workers to alternative employment, the envisaged manpower reduction of thirty-five per cent over seven years would be too drastic, he said, destroying the livelihoods and capital of not only the miners themselves but also their families, local merchants, schooteachers, doctors, etc. A reduction of twenty-four per cent would be more acceptable. Later that year, he said that the continued exceptional rise in unused coal stocks, which had now reached twice the normal level, was causing alarm. Demand for coal had been declining since its 1956 peak, as a result of oil encroachment, a special programme of oil for power stations, industrial recession and warmer weather. The import of cheap surplus fuel-oil from foreign refineries constituted a ‘severe threat’ to the coal industry.Footnote 40 In the future, however, continued productivity increases would help reduce the relative price of coal, while the absorption of the glut of oil would likely see its price rise. He remained optimistic about coal's future.

In a 1960 talk to the National Union of Mineworkers, he reiterated the now familiar arguments concerning growing energy needs, the vulnerability of oil and the inadequacy of nuclear energy.Footnote 41 There was no substitute for natural carbon, most of which was coal. Neither was there any substitute for oil used in internal combustion engines. In twenty years time, world requirements of coal would be substantially higher. Europe had no indigenous oil or natural gas. Add to this the prospective expansion of the world economy and the whole situation took on ‘an almost desperately dynamic quality, surpassing anything ever experienced in the past’.Footnote 42 Given this, the idea of closing collieries and working only the best seams was wrong. The coal would be needed in the future. It was important to preserve the coal reserves and the workforce.

* * *

Notwithstanding this air of professional assurance, Schumacher continued to be invaded by doubts that were eroding his faith in the economics profession. When he returned from Burma he was, by his own admission, ‘lost’: ‘I need some guide’, he wrote privately, ‘some guide-book for my life. Where do I find it? Religion tells me one thing; Science tells me another. What is more, Science tells me that religion is a superstition, that only “scientific” knowledge can be trusted. Yet I cannot find in scientific knowledge any answer to my questions – what am I to do with my life? Why am I here?’Footnote 43 Throughout the late 1950s he remained involved in the ‘Work’ of Gurdjieff-Ouspensky and with Subud, its successor in John Bennett's community, organising discussion groups at his own home.

By 1959 he was teaching a wide-ranging course on ‘“Philosophical” or “Crucial” Problems of Modern Living’ to continuing-education students at the University of London. It was essentially a course on the Perennial Philosophy, but also touched on Gurdjieff, yoga, and, perhaps inevitably, modern economics. His surviving notebooks contain remarkably wide-ranging lecture and study notes: Ortega y Gasset; R. C. Zaehner (Mysticism, Sacred and Profane, 1945); St. Augustine; Thomas Aquinas; M. Versfeld (The Perennial Order, 1954); Kierkegaard; Hume; Sartre; Solovyev; Fromm (The Sane Society, 1956), R. H. Tawney (The Acquisitive Society, 1920).Footnote 44 His fifth lecture on 28 October provided a summary of what they had covered so far. Man was created by God. There was a natural Hierarchy of Being: stone – plant – animal – Man. All religions saw Man as homo viator, capable of achieving salvation in some form. The perennial philosophy expressed itself in myth, fairytale, religion and literature (Plato, Dante, Shakespeare). The universal edict to love God and love one's neighbour led to politics. ‘It is hardly possible to think of politics today without thinking of Economics. We are not concerned with the technicalities of the so-called science of economics but with its philosophical basis. As it is always difficult to see oneself, unless one has some standard of comparison, we shall probably find it useful also to refer to the economics of so-called under-developed countries.'Footnote 45 In an oblique reference to Ananda Coomaraswamy, of whom Schumacher became a reader, he claimed that Beauty was not a diversion from the serious business of living: ‘Industry without art is brutality’. Looking at the various ‘Ways’ recommended to Man throughout the ages, one could ask: ‘Could there be a New Man and a New Jerusalem?’.Footnote 46

He devoted two evenings to economics in particular. ‘The Philosophy of Economics’ (Lecture No. 18) said that the crux of the matter in both capitalism and socialism was ‘the religion of economics’. Their shared belief that ‘Man liveth by bread alone’ led to ‘Degradation of the Higher; Contempt of the person – Misuse and alienation; Misuse of Nature’. To affirm the economic sphere as self-contained and independent of religion or the ethical sphere could lead to ‘nothing but disaster and sin’.

Lamentable metaphysical ignorance of economists, political and social scientists considers economics as a science with laws of its own – such as the law of supply and demand or Gresham's Law which must be respected irrespective of their human consequences.

Man, if treated as homo economicus, will ‘go to pieces’, will cease to be Man. Adam Smith's portrayal of the ‘alleged economic harmony’, built on the contention that consumption was the sole end of all economic activity, led to ‘Capitalism and with it a universal degradation of human life’. We need to ask: ‘what kind of economic life is appropriate and proper for human beings?’ It was undesirable to spread the Western system to the undeveloped countries, for our own life was ‘utterly impoverished’. That system was most dangerous where it was most successful: productivity and growth leading to physical exhaustion; science bringing mental impoverishment; large-scale organisation leading to slavery; the peaceful use of atomic energy bringing death. The only hope for the recovery of sanity lay in humility vis-à-vis the ‘higher’; pity for our fellow man; and loving care for the world of nature.Footnote 47

The second lecture, ‘The Double-life of a Post-modern Economist’, was both subversive and confessional. Modern economics was founded on a picture of man that had emerged with the natural sciences over the last 250 years. That picture was devoid of any of the eternal qualities associated with Christian, Greek, Roman or Islamic religious cultures. The modern age of ‘evolutionism, determinism, mechanism, materialism . . . idealism, and finally unlimited relativism’ had nothing to say about the place of man in the cosmos, and had created a ‘topsy-turvy world of values’. Clearly referring to himself, Schumacher said that the post-modern economist was forced to lead a ‘double life’. Yes, he favoured healthy growth, but not just any growth; yes, he was concerned with the means by which productivity could be raised, but really, in his heart and soul, he implied, he was uninterested in productivity.Footnote 48

The 1960s: Managing the Double-Life

While one could be forgiven for believing that such ruminations presaged a change of career, it would be a full decade before Schumacher could free himself from the ‘iron cage’ of modern industry. The turn of the decade was a difficult time for him and his family. In mid-1960 his wife, already ill, underwent surgery and was diagnosed with incurable cancer, and in late October of that year, after many weeks with him at her side, she died in a German hospital. The ordeal of bereavement appears to have drawn Schumacher closer to Christianity. He apparently spent hours lingering in churches in central London, began to give talks to religious groups and more clearly identified himself as a Christian.Footnote 49 His ethical critique of the world of commerce and industry sharpened accordingly. On the family front, by early 1962, Schumacher had announced to his four children that he and Vreni Rosenberger, their live-in au pair since late 1959, were to marry.Footnote 50 Thus began a new life, with the first of four more children soon on the way.

Thereafter, two divergent developments were set in motion in his life, to both of which labour and machines were central. Firstly, notwithstanding his private misgivings, he was drawn ever further into the world of coal and called on to play a central role in the process of rationalisation and mechanisation underway at the coal board. Secondly, acting on his private heresies, he deepened his involvement in debates on economic development in India and elsewhere, introducing and actively promoting the idea of Intermediate Technology. As a close friend said of him later, it was as if he were living two lives.Footnote 51

In 1960, Alfred Robens became Chairman of the National Coal Board. Cheap oil had been making inroads into British electricity generation, pricing coal out of the market.Footnote 52 Unlike his predecessor, Robens knew Schumacher well and decided to make proper use of him at the NCB, calling upon him to help manage an industry in decline and, the following year, making him Director of Statistics. Notwithstanding his ‘post-modernism’ and his evolving inner life, Schumacher now became a public spokesman for British coal production. His arguments were economic and quantitative: given the likely rise of future energy needs, it was highly improbable that the demand could be met by oil (given proven reserves) or by nuclear energy (given the huge capital investment required). It was thus necessary to preserve domestic coal, so that future demand could be met. Because of flooding, pits could not be closed down temporarily and reopened; miners could not be let go and called back several years later. It was also necessary to continue increasing the efficiency of the coal industry, through the proper selection of pits to be worked and, most importantly, through mechanisation.Footnote 53

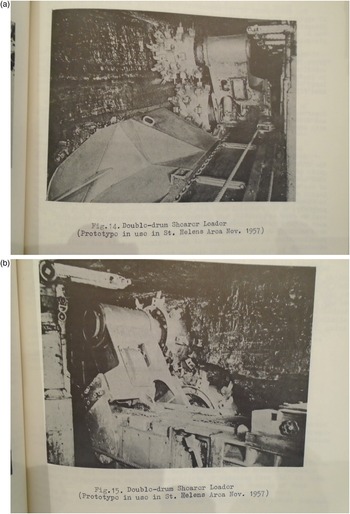

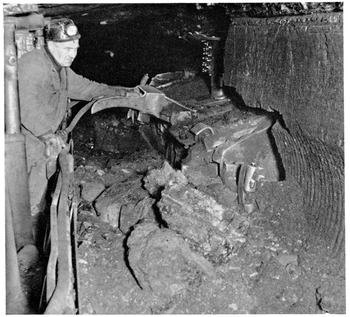

The latter involved the introduction of such equipment as the Atherton and Huwood Power-loaders, or the Arcwall Cutter and Samson Stripper, which ‘gnawed’ the coal from the face, thereby releasing men from the traditional task of chipping off the coal themselves with pickaxes. For the miners, this removed some of the physical difficulty of working the coalface, be it a high or low seam, and replaced it with shovel-loading and feeding. With longwall cutting, miners were now obliged to work as a team serving the machines, the work being organised around the ‘stint’, the time required for the machine to work completely across the face, have the coal removed, and then begin a new round. When a new shift began, it was essential that the face be clear and ready, as any delays could be very costly. In interviews, miners acknowledged the easing of the hardest old labour but also emphasised the loss of autonomy brought about by the constraint of serving the machinery.Footnote 54 There was also the increased heat and dust caused by the machines, and the heightened risk: before mechanisation, the mine was quieter and they could hear the cracking and other sounds that warned of danger; now, with the constant noise, those sounds could no longer be heard (Figures 1–7).

Figure 1. Miner drilling the coalface. (Photograph courtesy of the National Coal Mining Museum for England).

Figure 2. Miners handloading coal onto conveyor. (Photograph courtesy of the National Coal Mining Museum for England).

Figure 3. Arcwall Cutter on top of coal in roadway drivage. (Photograph courtesy of Peasely Colliery Museum).

Figure 4. Double-drum shearer loader.Footnote 65

Figure 5. Huwood loader in deep hard seam. (Photograph courtesy of Peasely Colliery Museum).

Figure 6. Huwood loader from front. (Photograph courtesy of Peasely Colliery Museum).

Figure 7. AB treppaner. (Photograph courtesy of Peasely Colliery Museum).

Working closely with Robens, Schumacher contributed to the drive towards increased efficiency. He was a member of the board's important ‘Collins Committee’ of the mid-1960s that oversaw further pit closures and layoffs.Footnote 55 Ironically, it was precisely because he was so useful to Robens that he was given the freedom to live his ‘double-life’, travelling abroad and doing the work that mattered most to him personally.Footnote 56

* * *

With his Burma paper, ‘Economics in a Buddhist Country’, published in 1959 by J. P. Narayan, Schumacher was soon invited to India, attending a conference in early 1961 at Poona, organised by the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics and the Congress for Cultural Freedom. His talks there were published the following year as a pamphlet, ‘The Roots of Economic Growth’, by the Gandhian Institute for Studies at Varanasi.Footnote 57

In his main address at Poona, ‘Help to Those Who Need It Most: Some Problems of Economic Development’, Schumacher criticised World Bank President Eugene Black who, in a recent paper, ‘The Age of Economic Development’, had emphasised the need for material economic growth, notwithstanding the social, psychological, moral or political changes that it might provoke.Footnote 58 Finding this attitude offensive, Schumacher said that while there was no denying the need to alleviate human misery, the idea that men ought to be driven in order to develop a Western work ethic, or that the practices of advanced countries were worthy of imitation, was highly questionable, especially given the ‘dehumanising deformities of the modern West’.Footnote 59 World Bank development programmes were bringing sophisticated production techniques and materially high living-standards to a small minority of the population, but at the cost of apathy and paralysis in the remaining eighty per cent. Some way had to be found of encouraging the ‘spontaneous mobilisation of this labour power’.Footnote 60 In both this lecture and in a talk on ‘Paths to Economic Growth’, Schumacher rejected an idea that would later become influential in the development literature, namely Walt Rostow's ‘beautiful theory . . . derived from aeronautics’ (p. 15), with its suggestion that a ‘take-off’ would occur when the right conditions were secured. Such a theory dealt in abstractions with which the people could not identify, said Schumacher, orienting them towards the unattainable conditions of the West rather than towards their own immediate reality.Footnote 61

The poverty and despair of millions of Indians were a historical aberration, he said. ‘All peoples . . . have always known how to help themselves; they have always discovered a pattern of living which fitted their peculiar natural surroundings’.Footnote 62 There had always been poor peasants and artisans, but ‘miserable and destitute villages in their thousands and urban pavement dwellers in their hundreds of thousands . . . in the midst of peace and as a seemingly permanent feature – that is a monstrous and scandalous thing which is altogether abnormal in the history of mankind’.Footnote 63 The underlying reason, he said, was the paralysing effect of the modern West, due to the suddenness and size of the changes being introduced. The implantation of a modern transport system exposed the regional towns and villages to competition from cheaper goods, produced in advanced factories in distant cities. Paraphrasing Ruskin via Coomaraswamy, he said that, rather than deny people their own livelihoods, it was necessary to ‘Find out what the people are trying to do and help them to do it better’.Footnote 64

In ‘Levels of Technology: A Key Problem for Underdeveloped Countries’, he laid out what would become his ‘Intermediate Technology’ idea. The main problem, he claimed, was the co-existence in developing countries of vastly different technology levels – the ‘bullock cart’ and the ‘jet engine’ – and the mistaken belief that it was possible to make a historical ‘jump’ from one to the other without going through the intermediate stages. After all, such development had taken centuries for the West. In the developing countries, he said, the isolated enclaves of advanced technology that had been created were damaging the rest of the economy by destroying regional production and splitting the society into rich and poor. Given that the opportunity cost of labour was so low, it would be better to focus on labour-intensive production, and encourage the creation of workplaces the cost of which bore some reasonable relation to Indian wages. Otherwise, technology would remain out of the reach of the people.

In November 1962, he returned to India for a six-week stay as advisor to the Indian Planning Commission, travelling around, visiting workshops and factories and speaking to people. He also spent time with Gandhi's disciple, Vinoba Bhave, the leader of the Bhoodan, or land-transfer, movement.Footnote 66 His report to the Planning Commission in New Delhi, which reiterated the need to choose cheaper technology and develop organically, was published in 1964 in India at Midpassage, the assessment by London's Overseas Development Institute.Footnote 67

That same year he confronted his Western economics brethren, presenting the Intermediate Technology idea to the Cambridge Conference on Development.Footnote 68 Western capital-intensive technology, which was intended to substitute for scarce labour, was inappropriate in countries where labour was in surplus. Better to create workplaces where they are needed, using simple methods and local materials. He criticised the ‘development “experts”’, who were unable to imagine production without all the trappings of the Western way of life: ‘electricity, steel, cement, near-perfect organisation, sophisticated accountancy (preferably with computers), not to mention a most elaborate “infrastructure” of transport and other public services’.Footnote 69 Development would have to rely on local materials, he said, and it was important to stem the loss of traditional knowledge of them. It was possible to have a productive agriculture by relying on organic methods, and to build durably without relying on cement. Attention ought to be given to the planting of trees, not least as a source of building material.

Schumacher's opinions provoked a memorable confrontation with the economists present, led by his former wartime colleague, Nicholas Kaldor, who accused him of promoting the waste of capital resources and the production of non-competitive goods.Footnote 70 Many of the Indian and African representatives, too, were dismissive, clamouring for the most advanced technological support available. In response, Schumacher published an Observer article, ‘How to Help Them Help Themselves’, in August of the same year, replying to the economists and further pressing the Intermediate Technology idea.Footnote 71

Earlier, in May, as a result of discussions between Schumacher, George McRobie, his assistant at the NCB, and Julia Porter of the African Development Trust, a group of about twenty volunteers had come together in order to do something to promote these ideas in developing countries. The outcome was the formation of the Intermediate Technology Development Group, the work of which became a personal mission for Schumacher.Footnote 72 Indeed, by the spring of 1965, precisely when he was most involved in its work of mechanisation and rationalisation, he was ready to walk away from the coal board. Strolling with Porter in St. James’ Park:

He took her by the elbow and propelled her along. For two hours or more he propelled her about, talking at her. She might as well not have been there. She was purely a sounding-board for his own ideas. It was freezing cold. He said: ‘I want out from the Coal Board. I want to concentrate my efforts much more on the IT, which I believe is crucial for the future. Now how can you guarantee that you can create an organisation that will support me in order to do that? I need some money to support two young children' . . . Julia said: ‘No way at the present moment. You have to make an act of faith, the same as the rest of us.'Footnote 73

Thus, with the ITDG unable to support him, and Robens needing him, he stayed on at the coal board, overseeing the mechanisation of the mines while, with greater personal conviction, promoting ‘tools’ abroad.

Figure 8. Cover of Tools for Progress (1967/8).

In 1967, after a year's research and preparation, the ITDG published its catalogue, Tools for Progress: Guide to Equipment and Materials for Small-scale Development (Figure 8).Footnote 74 An introductory article by Schumacher, which had earlier appeared in The Times, described the main task: namely, how to provide support to the great rural populations of Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America, if the problems of hunger, mass unemployment and uncontrolled urbanisation were to be mitigated. ‘To raise the level of agriculture, the whole level of peasant life has to be raised, and this means the development of an agro-industrial structure in the rural areas, so that each community can offer a large variety of occupations for its members.’Footnote 76 The tools and equipment in the catalogue were grouped under Agriculture, Building, Education, Fishing, Forestry & Woodworking, Handicrafts & Small-scale Manufacture, Handling, Measurement, Metal Working & Machine Maintenance, Power, Transport & Roadmaking and Water Supply. For every item illustrated, there was the name of a British supplier from whom it could be ordered.

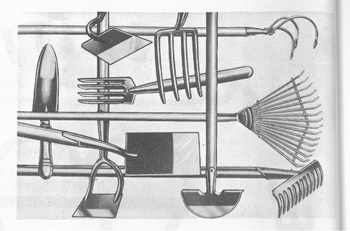

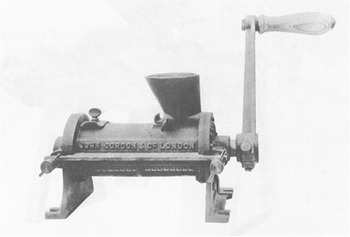

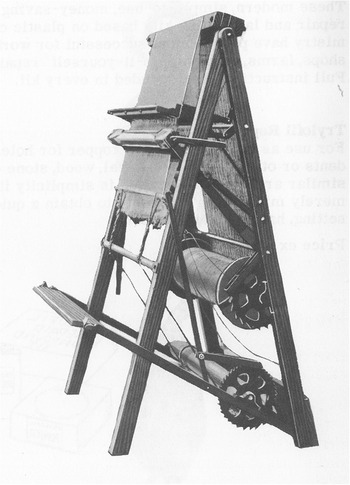

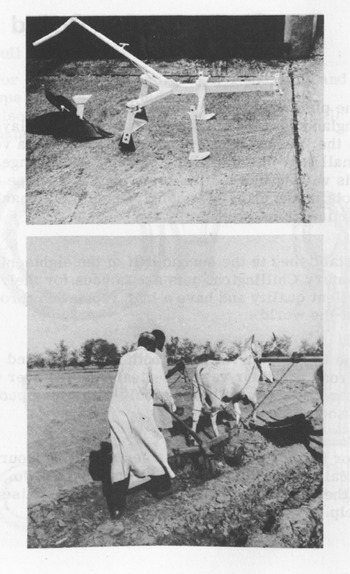

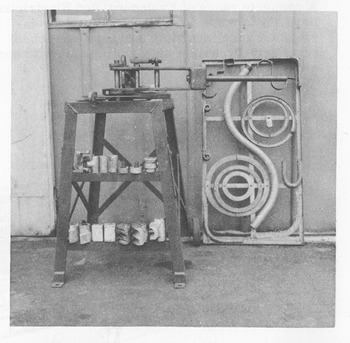

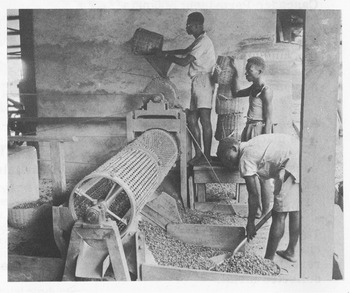

Many of the tools were used by hand or drawn by an animal. For example, the hand-tools included horticultural equipment, a rice huller and the ‘Drivall’ (Figures 9–11). For a hand-powered mat-making loom, details were provided on output per day of mats of various kinds (Figure 12). Amongst the animal-powered items was the Unibar, a cultivation tool that could serve variously as plough, harrow or hoe (Figure 13). The Norfolk metal bender allowed the manual shaping of pipe and other kinds of metal. (Figure 14). The nutcracking machine was for shelling peanuts, and could be driven by hand or by mechanical power (Figure 15).

Figure 9. Horticultural tools.Footnote 75

Figure 10. Rice huller.

Figure 11. The ‘Drivall’.

Figure 12. Mat-making loom.

Figure 13. The ‘Unibar’.

Figure 14. Norfolk metal bender.

Figure 15. Nutcracking machine.

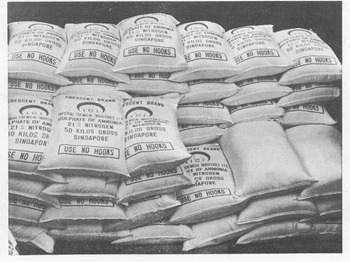

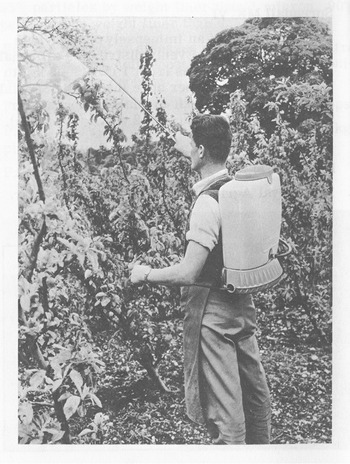

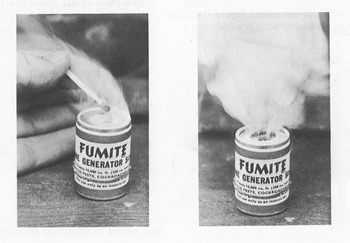

Note that while the general thrust of the catalogue was in keeping with Schumacher's traditionalist desire to maintain rural communities and allow people to remain on the land, it was far from being ‘ecologically pure’. Thus Imperial Chemical Industries, a giant like the coal board, and no friend of the Soil Association, offered artificial fertilisers, urea and ammonium sulphate (Figure 16). Although Schumacher had read Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962), the catalogue also advertised chemical crop-sprayers, and Fumite greenhouse smoke-bombs containing Lindane, Dieldrin or DDT (Figures 17 and 18). In a full-page advertisement for their insecticides, fungicides and herbicides, Shell Chemicals portrayed themselves as guarantor of cornucopia and tradition (Figure 19).

Figure 16. Artificial fertilisers.

Figure 17. Crop-sprayer.

Figure 18. Fumite smoke-bombs.

Figure 19. Shell Chemicals advertisement.

Yet, for all such pragmatic concessions, the catalogue was traditional in thrust. It also led to significant inquiries from various countries, in response to which, beginning in 1968, the ITDG formed its own support network of voluntary panels of experts, first in building, then water supply, and, shortly afterwards, agriculture, health and cooperatives.Footnote 77

From 1966, embracing his heterodoxy, Schumacher began writing in Resurgence, the magazine launched that year by John Papworth, with the help of Herbert Read and others, in reponse to ‘the problems of small nations, small communities and the general insanity of the prevailing pattern of existence, especially the evils of giantism as reflected in the problems of war, pollution and resource wastage’.Footnote 78 His first contribution was a reprint of the ‘Intermediate Technology’ paper that had set the cat among the pigeons at Cambridge.Footnote 79 This he followed with ‘Industrial Society’, a critique of modern industry that, like several subsequent articles, contained many veiled references to the coal board and his own work there.Footnote 80 Given what he was doing at Hobart House, the Resurgence writing appears consolatory, allowing him to say things he could never say at work. Agreeing with Tawney, he said that the founding of modern industry marked a total collapse of Christian standards of behaviour between men and the rise of the idolatry of wealth. A society in which economic efficiency became the ‘primary object’ outraged human nature by insulting self-respect and impairing freedom, and was thus necessarily destined to suffer recurrent revolt. It was necessary to question the idolatry of wealth and even the ‘legitimacy of economic growth’. The latter was a purely quantitative concept that needed to be defined in qualitative terms: some forms of growth were healthy, others were not. It is difficult not to think of the miners, when, in several places, Schumacher emphasises the need for society to develop a ‘philosophy of work’, namely, an idea of what was appropriate or fitting for the human being in the domain of labour, mechanisation and automation.Footnote 81

Taken together, Schumacher's Resurgence contributions speak to the dilemma in which he found himself in the mid- to late 1960s. While he would never criticise the coal board publicly, his allusions make it clear that he was disillusioned with the features of modern industrial society with which his work confronted him: heavy technology, difficult labour, industrial strife and the relentless talk of ‘efficiency’, ‘rationalisation’ and ‘productivity’ – and all for the extraction of a non-renewable fuel.

In 1970, he was eventually able to resign from the coal board and, in 1973, drawing some Resurgence essays and other chapters together, publish Small is Beautiful. When he died unexpectedly four years later, Papworth said of him that he had been ‘labouring to restore a tradition of Christian concern for the moral basis of economic activity which had been broken by the advent of capitalism in its unholy alliance with technology, and only reactivated by Ruskin, Tawney, and in his own way Gandhi, and others’.Footnote 82

Conclusion

Although Papworth's encomium captures Schumacher well, it says little about his protracted struggle for coherence. For the best part of twenty years, and especially during the 1960s, Schumacher sought to balance his professional involvement in the modern industrial world with a growing personal commitment to a different view of economic development. The coal board was the realm of the ‘Samson Stripper’ and the ‘stint’ – a world of heavy technology, mechanisation, industrial conflict and pit closures, men serving machines, the economic imperative all-powerful. Through his private teaching and, in particular, writings in Resurgence, Schumacher expressed his growing disillusionment with it all.

His deeper commitment – in those countries where there was still a choice – was to the disappearing world of Coomaraswamy's ‘Hand-Loom’, namely labour-intensive, appropriate technology; tools rather than machines, where the ‘craftsman's fingers’ were still required, so to speak, and the human element of the work thus conserved. Through Intermediate Technology, Schumacher sought to challenge the iron laws of ‘economic efficiency’, brake the exodus from farms and villages and slow the destruction of traditional patterns of work and habitation. Few were the economists who thus sought to resist the march of modernity across landscape and human culture.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments on earlier drafts, I am grateful to participants at the Harvard-Uppsala workshop on ‘The Ecology of Economic Thought’; two anonymous referees and the editor of this journal; and Abhay Ghiara. For access to the Schumacher family papers in London and the archives at the Schumacher Center for a New Economics, I thank Barbara Wood and Susan Witt, respectively. For permission to quote from the archival material, I am grateful to Vreni Schumacher. For kindly providing photographs, I thank the National Coal Mining Museum of England and Stefan Thatcher of Pleasely Colliery Museum, UK. Finally, I thank the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant No. 435–2021–0893) for their financial support and Yohann Demierre for research assistance.