One evening, I was sitting with Allah Baksh Baloch in a cramped room adjacent to his house that served as his baithak (guest room). We were caught up in deep conversation over a book, when one of his friends entered suddenly. He noticed the physical copy of the book next to Allah Baksh. Gazing over at its cover, which had the face of a bearded man, the friend asked: “What pir are you reading about? What pir is that?” The friend assumed, based on his ragged and unkempt beard, that the man on the cover was some Sufi spiritual leader (pir), figures that are quite popular in this part of rural Pakistan. Allah Baksh responded:

Why he’s the greatest pir that ever lived!

Why do you say that?

What are pirs anyway? They have special powers to solve people’s problems. In that respect, the person on the cover is the greatest of all pirs because he tackled the root cause of people’s problems.

The book was actually a short summary, in Urdu, of volume 1 of Marx’s Capital, and the bearded fellow on the cover, who the friend assumed was a pir, was none other than Karl Marx.

Allah Baksh went on to draw several parallels between Sufism and Marxism. He suggested that it was significant that Marx and Khwaja Ghulam Farid, a popular pir here, both sported large, untrimmed, and ragged beards. Through their untidy appearances, both embodied a skepticism of appearances, of the way things first appeared (think also, for instance, of Marx’s discussion of “the commodity”).Footnote 1 Both Sufism and Marxism participated in a shared project of uncovering the hidden essence of the world—struggling, in other words, for Truth (Haqiqat or al-Haqq, an Arabic word for Truth that is also one of God’s names in Islam). We see this intersection as well, Allah Baksh continued, in Sufi poetry. These poets typically centered their poetry on the figure of the Mahbub (Beloved), understood to be both a longed-for lover and God Himself—a combined love for both humanity and Truth that, at least for Allah Baksh, also motivated communists. Ultimately for Allah Baksh, “Marxism [was] simply a logical continuation of Sufism.”

He had learned about this relationship from Sibghatullah Mazari (hereon Sibghatullah) (d. 2000). In the early 1970s, Sibghatullah, who belonged to a poor tenant family, led anti-landlord agitations in his village in a peripheral region of South Punjab. Soon, he, like a teenaged Allah Baksh, was recruited by the communist Mazdoor Kisan Party (MKP) (Worker Peasant Party), a party which, inspired by Maoism, had begun organizing peasants against “remnants of feudalism”Footnote 2 in the countryside, especially in Punjab and the North-West Frontier Province,Footnote 3 with the goal of establishing a “mazdoor kisan raj” (worker-peasant rule).Footnote 4 Though sharing a background with those typically led by communist leaders, glossed as “the masses” in their propaganda, Sibghatullah would quickly join the leading ranks of the party, becoming a member of its central committee and later vice-president of its Punjab branch, in large measure because of the momentum of his local movement. This momentum was attributable, in part, to Sibghatullah’s theoretical and political practice, which established an equivalence between Marxism and Sufi Islam: what I call his “mystical Marxism.” As I will show, he established this equivalence at both the immediately political level, arguing that both Sufism and Marxism necessarily opposed the “feudal” system (jagirdari nizam, simply jagirdari), and at a deeper philosophical level, suggesting that both were committed to Truth. Because of this reconciliation, Sibghatullah, the communist leader, came to be known as “Sufi Sibghatullah” and a “Truth-seeker” (Haqiqat-pasand).

In this paper, I historically reconstruct the life of Sibghatullah, a figure widely admired in the region though little known in Pakistan generally, because of the unrealized possibilities he represented. Too often, historiography has privileged histories of experience over what Reinhart Koselleck calls “horizons of expectation”—those possibilities latent in the past and not-yet materialized in the future.Footnote 5 Though Sibghatullah did not achieve his political objectives, his life evokes several possibilities. In a world of conflict-ridden difference, it shows the prospects for forging those unities—in this case, between religious and secular thought—that may be necessary for liberation. And against those scholars (discussed shortly) who have tried to reconcile Marxism and religion in scholarly prose, Sibghatullah’s life also reveals how a subaltern actor might come to theorize this equivalence in the context of political struggle—how a religious Marxism might look as both a theoretical and political practice.

Various circumstances led Sibghatullah toward this articulationFootnote 6 of Marxism and Islam, including his poor peasant upbringing amidst a landlordism that wielded Islam to reproduce its hegemony, contingent encounters with communist and progressive religious leaders during the popular upheavals of the late 1960s and 1970s, and shifting agrarian political-economies consequent to the 1972 land reforms. However, Sibghatullah’s theorizing, like arguably all theory-making, was also relatively autonomousFootnote 7 from these determinations, meaning the presence of certain distinctive ideological elements inhering to Maoism and Sufism specifically could also inspire an articulation. While several scholars have noted that Marxism and religion share a commitment to a theoretically informed practice, it was Maoism’s specific attention to a vernacular-driven universalism, combined with Sufism’s own universalist possibilities, that enabled Sibghatullah to articulate the two. His introduction to the party’s Maoism—another ideology, whose politics of the “mass line” and broader philosophy on practice meant it straddled the universal-vernacularFootnote 8—encouraged him to comparatively reflect on various Islams in the region, including his own. Sibghatullah specifically engaged with circulating Sufi ideas, including Sufi-inflected Deobandism, which appealed to him because of their universalist possibilities, possibilities inhering in their concept of Truth (and relatedly, humanity).Footnote 9 This engagement culminated in Sibghatullah establishing an equivalence between Marxism and Sufism, as both, in his view, struggled for Truth. Most basically, while Maoism’s vernacular orientation led Sibghatullah toward Sufism, it was their shared universalist elements that then enabled him to equate the two: an equivalence forged, as Aimé Césaire once put it, as “a universal enriched by all that is particular.”Footnote 10

Sibghatullah expressed this mystical Marxism not only in his prose, but in his political practice. He transformed the master-apprentice relationship at his workshop into a revolutionary Sufi pir-murid (guide-disciple) one, mobilized his disciples to organize in their own villages, recruited Sufi-inflected mullahs/maulvis into the party, organized annual “mullah congregations,” built insurrectionary Islamic institutions, and challenged the tribal landlords’ patriarchal “honor” codes. These practices, by undermining landlordism’s hegemony over Islam, threatened its reproduction.

To explore his theory and practice of mystical Marxism, I draw on twenty months of ethnographic research, oral histories, and a hitherto under-explored set of archives, including police surveillance files, the MKP’s internal literature, and the private notebooks of Sibghatullah and his comrades. In the paper’s first section, I briefly consider how different scholars—specifically, Marxist and Marx-inspired scholars, progressive religious thinkers, and critical realists—theorized the relationship between Marxism and religion, so as to situate Sibghatullah’s own theory-making. In the second section, I discuss Sibghatullah’s early life in order to unearth those encounters and contexts that would later shape his mystical Marxism: the prehistory of mystical Marxism. In the third section, I show how Sibghatullah’s theorization was made possible by the vernacular orientation of Maoism and the universalist possibilities of Sufism. The next three sections deal with different ways Sibghatullah expressed his mystical Marxism: one centers on his prose, another on his political practice, and the third details his later contestation against the tribal landlords’ patriarchal “honor” codes, which I view as another instance, and development, of his mystical Marxism.

Theorizing between marxism and religion

While a vast literature deals with Marxism and religion, here I focus on those strands that have aimed to establish some correspondence between the two: specifically, Marxist and Marx-inspired scholars, progressive religious thinkers sympathetic to Marxism, and lastly, critical realists. While Marxists, Marx-inspired scholars, and progressive religious thinkers have all noted some similarities between Marxism and religion, most all have argued for one over the other. Philosophers of critical realism, on the other hand, rigorously theorized a genuine rapprochement, and in a way that resembles Sibghatullah’s own mystical Marxism.

Marx and Marxists have noted parallels between Marxism and religion. When Marx famously argued that religion was “the expression of real distress and the protest against real distress,”Footnote 11 he was implying that what drew the masses to revolutionary Marxism could also drive their religious fervor: an implication made explicit when Friedrich Engels likened Christianity to “every great revolutionary movement,” since it too was “made by the masses.”Footnote 12 It was the Italian communist Antonio Gramsci who articulated a parallel between religion and Marxism in a more robust way. He believed that religion, like Marxism, was “a conception of the world and a corresponding norm of conduct.”Footnote 13 Religion, in other words, aspired for a unity of theory and praxis much like Marxism did, and Gramsci saw in subaltern religious beliefs and attachments a radical desire for theoretical-practical coherence.Footnote 14 According to Louis Althusser, even Vladimir Lenin, though critical of religion, also respected the religious on precisely these grounds; that they, unlike many philosophers, were “integral people … who have a ‘system’ which is not just speculative but inscribed in their practice.”Footnote 15 In summarizing the parallels between Marxism and Islam, Maxime Rodinson emphasized this shared commitment to a theoretically informed practice: both are “militant ideological movements having a temporal socio-political programme….”Footnote 16

Still, despite acknowledging these parallels, these Marxists believed religion and religious consciousness had to be superseded. Workers must be liberated from the “witchery of religion,”Footnote 17 Marx proclaimed, while Engels insisted that religion was “incapable for the future of serving any progressive class as the ideological garb of its aspiration.”Footnote 18 Gramsci articulated a rigorous reason for this supersession. He argued that Marxism, as a “philosophy of praxis” Footnote 19 whose theory evolved in mutual interaction with the changing practical world, could meet subaltern aspirations for theoretical-practical coherence in a way conventional religion could not, which in his view always tended towards orthodoxy.Footnote 20 To Gramsci, Marxism was simply a better, more adaptive religion—a secular religion.Footnote 21

Yet Gramsci held a rather static and un-dialectical conception of conventional religion, instead of viewing it as a site for class struggle, whose theoretical coordinates and corresponding practice could change: a point made by others,Footnote 22 and which Sibghatullah’s interaction with Sufism shows as well.

Later Marx-inspired scholars acknowledged religion’s malleability and transformative possibilities, but still suggested that religious consciousness had to be overcome in the end because it undermined the formation of a universal revolutionary subject. Frantz Fanon, for instance, in his exchange with Iranian-Muslim revolutionary Ali Shariati, acknowledged the revolutionary and anti-colonial possibilities of Islam, but saw that it was too particularistic. He cautioned that “reviving sectarian and religious mindsets” could “divert that nation yet to come … from its ideal future”: that future ultimately being a universal one.Footnote 23 Others suggested that religious consciousness would inevitably be replaced with a secular-universal one with the development of capitalism. Asef Bayat, for instance, attributed the Muslim World’s earlier affinity for an Islamic, as opposed to a secular, socialism to “its slow pace of modern class formation,” the assumption being that capitalist development would replace this religious socialism with “secular class politics.”Footnote 24 A fuller expression of a similar point came from Ranajit Guha. In emphasizing the role of religion in the nineteenth-century anti-colonial Birsa Munda rebellion, Guha still insisted that religion was simply a subjective “mediation” for class consciousness, a “discrepancy that is necessarily there at certain stages of the class struggle” (my emphasis).Footnote 25

In contrast, Sibghatullah’s theoretical practice did not conceive of religion as simply an idiom to mediate class struggle, one to be later superseded by a “mature”Footnote 26 secular class consciousness. Rather, he aimed to establish a religious consciousness that was equivalent to a revolutionary class one: an equivalence centered on the concept of Truth.

By centering this rather existential concept in his mystical Marxism, Sibghatullah also ameliorates some concerns progressive religious scholars have had with Marxism. While many, like liberation theologian Harvey Cox,Footnote 27 affirm the value of Marxist concepts and methods, Marxism by itself is viewed as insufficient. As Cornel West argued, Marxism fails to speak to “the ultimate facts of human existence”: it does not supply “existential wisdom.”Footnote 28 For similar reasons, Shariati also critiqued Marxism, arguing that it reduced man to “clay”—a metaphor in Islamic discourse for what he calls “objective material existence.”Footnote 29 While he conceded that Marxism acknowledged a contradiction between human agency and material constraints or structure, it resolved this contradiction, in his view, in favor of the material through its concept of material determination. In doing so, Marxism, in Shariati’s reckoning, denied a definitive feature of human beings: their capacity for independent (and thereby non-deterministic) moral agency and responsibility. In contrast, Islam, while recognizing humankind’s material qualities, also affirms a moral agency not reducible to material constraints. For Shariati, it is in this irreducible moral agency that the divine spirit is located, the “transcendental dimension of human existence”Footnote 30: a dimension that gives meaning to values. He believed that without these values there could be no basis to oppose capitalism, and that when Marx and Marxists do oppose capitalism on the basis that it degrades humanity, they adopt a “mystical tone” that goes against their own principles of historical materialism.Footnote 31

In essence, progressive religious scholars like Shariati oppose Marxism on two interrelated grounds. First, that Marxism’s historical materialism denies humanity’s moral agency, an agency religious thought upholds, and which is constitutive of humanity’s full existential nature. And second, without an appreciation of this moral dimension, Marxism has little basis, within its own logic, to oppose capitalism. Both assumptions, however, were challenged by critical realists, who, more than the other scholars discussed thus far, rigorously theorized a rapprochement between Marxism and religion.

With respect to the first objection, critical realist Andrew Collier argued that religion (in his case, Christianity) could still accommodate historical materialism, especially if the latter was seen as a “regional materialism.”Footnote 32 That is, Marxism’s materialism was only relative to history, and its material determination never precluded human agency.Footnote 33 Though Collier deploys the Lutheran doctrine of fallenness to legitimize his belief in historical laws operating (relatively) autonomous from God, Rodinson (though not a critical realist) finds this in Islam as well: “If God acts through the intermediary of natural law [as Muslims believe], why should He not act in the human world through the intermediary of social laws?”Footnote 34 Rodinson goes on to say that the classical Muslim sociologist Ibn Khaldun partly explained the appearance and rise of the Prophet in this way, with the social laws understood as secondary causes.Footnote 35 In essence, both Collier and Rodinson suggest that a commitment to a (historically-relative) materialism can coexist with a religious belief in transcendental Truth, God, and moral agency. We see this coexistence in Sibghatullah’s mystical Marxism as well, except he went further to equate the material struggles against landlords with the affirmation of Truth.

With respect to the religious scholars’ second objection—that without values, Marxism by itself has no grounds to oppose capitalism—it rests on a Humean distinction between facts and values, a distinction that critical realists breached. Roy Bhaskar, for instance, argued that facts are also values in any system of discourse (and, for him, this is basically most discourse) which values truth over falsity.Footnote 36 It followed that any system that obscured the truth and reproduced itself by falsehoods should be opposed by any discourses concerned with truth (again, this is most discourse for Bhaskar). To him, that system that reproduced itself by falsehoods was capitalism. Essentially, Bhaskar was aiming to show how the internal epistemological logic of social science compels it to be against capitalism (if we assume, as he did, that capitalism relies on obscuration to reproduce itself). Against those religious scholars discussed earlier, Bhaskar suggested that Marxism had within itself a logical and value-laden basis to oppose capitalism.

We will see that Sibghatullah’s theoretical reconciliation mirrored the efforts of critical realists. To him, both Sufi and Marxist thought were concerned with demystifying reality in order to reach Truth, and thus should oppose, by their own internal logic, any system that obscures this Truth (in his case, jagirdari). To Sibghatullah, both Sufi and Marxist logics were equivalent, and essentially embraced a dialectic that negated society-as-is in order to affirm Truth.Footnote 37 Even initially secular critical realists like Roy Bhaskar would eventually take their own “spiritual turn” for somewhat similar reasons, as their search for “the Real” took them toward God as the Ultimate Reality.Footnote 38 But whereas critical theorists have pursued this rapprochement between religion and Marxism in scholarly prose, my aim here is to show what conditions would enable someone outside the academy—in fact, a poor peasant with little formal schooling—to engineer it, and with what consequences for political practice. That is, I write a historical ethnography of religious Marxism, exploring the conditions for its emergence and its expression as both a theoretical and political practice.

Political practice was at the center of the dispute between Shariati and Fanon referenced earlier. In signing off his response, Fanon wrote: “although my path diverges from, and is even opposed to yours, I am persuaded that both paths [a universalist Marxism against what he saw as Shariati’s too particularistic Islam] will ultimately join up towards that destination where humanity lives well.”Footnote 39 Just short of a decade after Fanon’s death, Sibghatullah would aim to forge precisely such a union, unknowingly fulfilling Fanon’s desire to reconcile with Shariati. I turn next to how he did so.

A Prehistory to mystical marxism

Sibghatullah’s early milieu and encounters would go on to shape his theoretical and political practice. Because of how landlords in his village mobilized Islam to legitimate their rule, Sibghatullah, after he enrolled in the MKP, became increasingly convinced of the need to re-theorize Islam to further emancipatory politics. His re-theorization was shaped by his contingent encounters with various socialist Islams circulating at the time.

Sibghatullah was born in 1944 in Bangla Icha, a village in the former “Punjab Frontier” (now South Punjab) district of Dera Ghazi Khan.Footnote 40 This region is distinct from the rest of the Punjab province due to the presence of Baloch tribes, typically headed by a single hereditary chief (tumandar) and various petty chiefs (sardars). After Punjab’s annexation in 1849, those chiefs that submitted to British rule bolstered their own authority by formalizing a legal jurisdiction over their tribesmen and acquiring immense landed estates, known as “batai jagir estates.”Footnote 41 On these estates, landlords (jagirdars) collected both land revenue from peasant proprietors and rents from their tenants.Footnote 42 Sibghatullah’s family were poor tenants for one of these Baloch petty-chiefs named Ashiq Mazari, from the Mazari tribe.

The other group of landlords around Sibghatullah’s village belonged to the Makhdooms, who, together with the Baloch chiefs, sat at the helm of the jagirdari system. While Baloch chiefs tried to secure their legitimacy by mobilizing tribal fidelities, Makhdoom landlords used, as one of Sibghatullah’s comrades (sathi)Footnote 43 put it, “the medicine of spirituality.” Makhdoom landlords claimed common descent from Prophet Muhammad and used this genealogical assertion—the ideology of “Syedism”Footnote 44—and their patronization of local Sufi shrines as a way to legitimize their landholdings. Not only did some see Makhdooms as pirs, but others even “consider[ed] the Makhdoom alongside Allah.”Footnote 45

But circulating alongside this elite Sufism was an anti-landlord, insurgent Islam—that of Ubaidullah Sindhi (d. 1944), the “Imam-i-Inquilab” (Imam of the Revolution).Footnote 46 A Deobandi by training, Sindhi would give this otherwise puritanical and scripturalist Islam both Sufi and politically-subversive twists. He did so by drawing on Deobandism’s own genealogy, specifically the writings of Shah Waliullah (d. 1769), whose critiques of the Persian and Byzantine ruling elitesFootnote 47 and emphasis on mystic Ibn al-Arabi’s (d. 1240) universal concept of “unity of being” (wahdat al-wujud)Footnote 48 enabled Sindhi to create a “pseudo-Wali-Ullahi communism.”Footnote 49 Though historians typically suggest it was Sikh Jats in central and eastern colonial Punjab who were more receptive to communist ideas,Footnote 50 Sindhi’s political thought reveals an early Muslim engagement in the province, one that would go on to shape Sibghatullah’s own thinking. Sindhi in fact spent his childhood in Jampur, a town just north of Sibghatullah’s village, before moving to neighboring Sindh (where he engaged with the region’s Sufi pirs) and then onward to the center of Deobandi teaching at the Dar al-‘Ulum Deoband in the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh). After traveling to Afghanistan, and then to the Soviet Union in 1922—becoming one of the first Muslim thinkers to directly encounter Russian communismFootnote 51—Sindhi would return to the Sindh/South Punjab region in 1939 to propagate his distinct Sufi and socialist-inflected Deobandism. His adopted son would continue spreading this Islam in Punjab’s countryside.Footnote 52

While both Makhdoom’s Sufism and Sindhi’s (Sufi-inflected) revolutionary Deobandism would later shape Sibghatullah’s interaction with Islam, neither directly influenced him in his early years. “He was just an ordinary Muslim,” his peasant comrade Malik Akbar told me, “he had a beard, and prayed.” What did directly impact Sibghatullah during this period, according to Malik Akbar, was encounters in Karachi, where he moved in the late 1960s to find work. It was there that he trained to be a television and radio mechanic, a trade whose relations of production (specifically the master-apprentice relation) would, as we will see, play an important role in Sibghatullah’s “mystical Marxist” practice. It was also in the city that Sibghatullah encountered radical ideas and politics, since the late 1960s and early 1970s was a period of popular upheavals in the city and surrounding countryside.Footnote 53 Not only did he befriend striking workers in Karachi’s Landhi/Korangi industrial area, but he also met some peasant leaders from the Sindh Hari Committee, an organization mobilizing Sindh’s landless peasants (haris) against landlords.Footnote 54

According to Master Sajid Mallick,Footnote 55 a retired schoolteacher and another former comrade, Sibghatullah may have even encountered the person behind the Committee, G. M. Syed (d. 1995), who was known to entertain various political dissidents in his Karachi home.Footnote 56 Similar to what Sibghatullah would go on to do, Syed and his protege Ibrahim Joyo (d. 2017) delinked Sufism from landlordism and combined it with Marxism (in addition to other philosophies and religions). To Syed, Sufi mysticism went beyond doctrine and ritual to center, instead, the “unity of being,” a mystical core Syed believed was present in all religions, making Sufi mysticism compatible with even non-Islamic religions.Footnote 57 In drawing on Ibn al-Arabi, Syed’s thought paralleled Ubaidullah Sindhi’s, though the latter (as a Deobandi) was more rooted in Islam’s foundational texts than the former. Moreover, while emphasizing Sufism’s universalism in his theoretical writings, Syed, unlike Sindhi, would stress its vernacular dimensions in his politics. Syed located Sufism as part of the distinct heritage of the Sindhi homeland (Sindhudesh) in order to legitimize his argument for Sindhi separatism.Footnote 58 Though Sibghatullah would, once he joined the MKP, take a different approach to reconciling Sufi Islam and Marxism, emphasizing (akin to Sindhi) the former’s universalism over its vernacularization, his early encounters with Syed’s “reformed Sufism”Footnote 59 may still have alerted him to the universalist and insurgent possibilities inhering in Sufism.

Sibghatullah’s exposure to these sorts of subversive ideas in Karachi was cut short after his wife, who had remained in his village, was murdered. Returning to Bangla Icha for the funeral in the early 1970s, he discovered that his elder brother had committed the murder. Invoking Baloch tribal custom (qaba’ili rusum), the brother claimed Sibghatullah’s wife had committed illicit sexual relations with another man and become dishonored (kali/kari). As his son told me, Sibghatullah never believed the accusation, and always suspected that it was his elder brother who had made uninvited sexual advances on his wife. According to Master Sajid, this incident led Sibghatullah to start questioning not only the tribal “honor” codes (kali qanun) but the very notion of tribe, whose internal integrity these codes aimed to uphold. Though Sibghatullah would later confront tribal authority directly, this early incident, combined with his exposure to peasant militancy in Sindh, did nevertheless lead him to his first political action.

Shortly after establishing a TV and radio repair shop in a town adjacent to his village, Sibghatullah surprised many by ignoring tribal fidelities to assist a group of Punjabi Jat tenants, who were being evicted by the Makhdoom landlord Ghulam Miran Shah. What set the stage for these sorts of tenant agitations, which occurred across the country, was the 1972 land reforms of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (d. 1979), Prime Minister and populist leader of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). The reforms included a land ceiling, greater tenant protections, and incentives for landlords to modernize farming.Footnote 60 Like landlords elsewhere,Footnote 61 Ghulam Miran Shah evaded state appropriation of his above-ceiling land by transferring it, on paper, to his relatives and managers. But influenced by the reform’s modernization incentives, and fearing its greater tenurial protections, the Makhdoom landlord also resumed over 100 acres from his Jat tenants, placing it under “self-cultivation” (a euphemism for wage-labor-based production). According to Master Sajid, Sibghatullah assisted these tenants in their struggle to stay on the land as tenants, a struggle that at this stage, the comrade pointed out, did not necessarily aim to overturn jagirdari. The Makhdoom landlord not only refused to accept the tenants’ demands, but he evicted Sibghatullah from his repair shop, which stood on land that fell within his estate.

Though this movement failed, it did, according to Master Sajid, shape Sibghatullah’s later critique—articulated in the form of a mystical Marxism—that jagirdari was inherently exploitative. It needed to be abolished, not reformed. His leadership of this movement, news of which began circulating throughout the region, also led him to the MKP, and specifically to the party’s then Punjab provincial secretary Imtiaz Alam, who was looking to expand party work to South Punjab.

Maoism meets mysticism

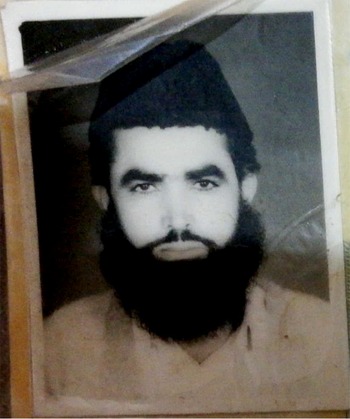

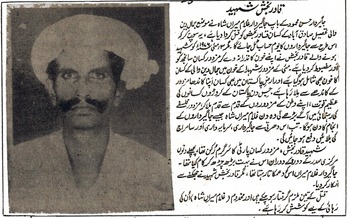

I met Imtiaz Alam on several occasions in his office in Lahore, Pakistan’s second largest city. Though born to an elite “feudal” family from South Punjab, Imtiaz would go on to become a socialist student leader in the 1960s at Lahore’s Punjab University, before becoming frustrated with the “petty-bourgeois” orientation of student politics and joining what he saw as the more revolutionary, mass-oriented MKP.Footnote 62 When I asked Imtiaz about Sibghatullah, with whom he developed a close friendship, he told me that when they first met, he was surprised to see that the leader he had heard so much about looked like a “simple” villager, dressed in a dhoti (cloth around lower half of the body). But in these first few encounters, Imtiaz witnessed for himself how “sharp, methodical and organized” Sibghatullah was, and quickly convinced him to join the MKP. Sibghatullah, for his part, was more than happy to join the party after realizing that wider and external support was needed to confront landlords like the Makhdooms (image 1). Though Sibghatullah would in time become the party’s Punjab vice-president, forming MKP units across South Punjab,Footnote 63 and becoming, in Imtiaz’s words, “the most outstanding peasant leader in the region,” he kept his simple appearance and demeanor. Quite different from many left leaders in Pakistan, this appearance and background turned out to be advantageous for the party. “He kept his lifestyle,” Imtiaz recalled, “which was good. It didn’t intimidate the peasantry.… And he was a good example for our upper-middle class leaders and cadres.”

Image 1: Sibghatullah around the time he joined the MKP, ca. early 1970s. Courtesy of Qayum Mazari.

To his credit, Imtiaz at the time had also tried to shed any vestiges of his elite background—wearing shabby clothes, keeping an unkempt beard, and becoming what he called a “pauper revolutionary”—in order to “de-class” himself. Common amongst Maoist parties elsewhere,Footnote 64 “de-classing” was one aspect of the MKP’s politics of the “mass line,” a politics inspired by Mao Tse-tung. Mao summed up the “mass line” as follows: “Take the ideas of the masses (scattered and unsystematic ideas) and concentrate them (through study turn them into concentrated and systematic ideas), then go to the masses and propagate and explain these ideas until the masses embrace them as their own, hold fast to them and translate them into action.…”Footnote 65

Mass line politics meant that a communist party’s theory and program should evolve through an engagement with “the masses.” The politics was part of Mao’s wider philosophy of practice—a “dialectical materialist theory of knowledge”Footnote 66—whereby revolutionary theory should evolve through mutual interaction with political practice amongst subaltern classes. Put in Fanon’s words, this philosophy aimed to create a revolutionary party that was neither a “mimic man who nods his assent to every word by the people” nor one that “regiment[s] the masses according to a pre-determined schema.”Footnote 67 Rather, the party and its revolutionary theory should adjust to reflect the vernacular concerns of the masses, at the same time as it should push the latter in a revolutionary and universalist direction.Footnote 68 It was this combined commitment to both the universal and vernacular that facilitated Maoism’s global travels and solidarities during that period.Footnote 69

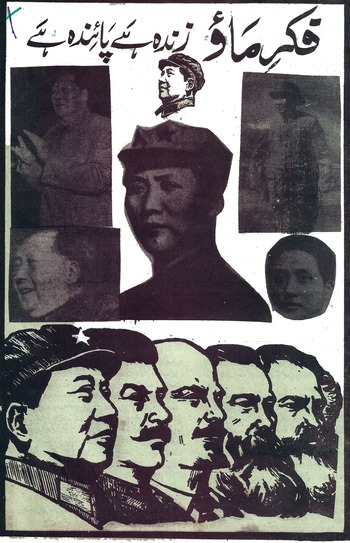

Like peasant-oriented revolutionary parties across the global South, the MKP was heavily influenced by Maoist philosophy, especially as several party leaders had once been aligned to the faction of the National Awami Party (NAP) led by East Bengali peasant leader Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani (d. 1976), an admirer of Mao who traveled to China in 1963.Footnote 70 At meetings with peasants and workers across the country, MKP leaders like Afzal Bangash (d. 1986) “emphasized the need for building a new Pakistan on the philosophy of Mao Tse-tung” (image 2).Footnote 71 To implement this philosophy, one centered on “the masses” (awam), the party first needed to immerse themselves in the masses, which MKP leaders did not believe previous Pakistani communists had done. Speaking about leaders of the banned Communist Party of Pakistan (who frequently held their meetings in English), MKP president Major (retired) Ishaq Muhammad (d. 1982) noted, “[The CPP leaders] were culturally alienated from the soil … [they] had no love, no link with the people of the soil.”Footnote 72

Image 2: “Maoist Thought Is Alive and Well.” Page from the MKP’s internal party circular: Circular 77 (Oct. 1976).

In addition to “de-classing,” the MKP’s national leaders aspired to build that link through various practices. For one, they directly participated in ongoing tenant movements during that period, even if their demands were not necessarily revolutionary. For instance, shortly after Sibghatullah joined the party, Major Ishaq visited tenants in his region who were demanding, not the abolition of jagirdari entirely, but only a fairer, more transparent sharecropping arrangement (hissa-batai) with their Baloch landlord Ashiq Mazari.Footnote 73 Ishaq went so far as to use his fame and legal background to free those tenants who, after refusing to sharecrop until their demands were met, were imprisoned in Mazari’s private jails: “The jagirdars and bureaucrats got quite scared about Major Ishaq’s presence here,” Sibghatullah wrote at the time, “so they released the 30 men from their private jails.”Footnote 74

National leaders also built the missing link with the masses by conducting several investigative (tahqiqati) reports on rural Pakistan,Footnote 75 elevating local languages over national languages like Urdu and English,Footnote 76 and, important for my purposes here, engaging with Islam. Leaders would frequently begin their meetings by invoking Allah and would raise “Allah-o-Akbar” chants at rallies. At one of those rallies in South Punjab, Major Ishaq even likened the peasant struggle against landlords to Prophet Muhammad’s fight against his enemies: “The people who scare us, who martyr us, they are all Abu Jahal and Abu Lahab [the Prophet’s enemies].”Footnote 77 During their village tours, MKP leaders would often stay at village mosques, pray, and concertedly engage with local imams. While other notable Pakistani leftists at the time subtly mocked the party’s engagement with Islam,Footnote 78 implying that it contravened how a proper (i.e., atheistic) communist party should act, MKP leaders saw this as necessary to build a mass-oriented movement.

Still, the MKP leadership’s interaction with Islam remained largely strategic, limited to these sorts of overtures. Though they certainly did not want to speak out against Islam, neither did they want to conduct a concerted ideological struggle over the religion. At a central committee meeting for the MKP’s Punjab branch, Major Ishaq “forcefully said that the [party] workers should stop this bakwas (idle talk) on religion, and insisted that they should promote the teaching of scientific socialism.”Footnote 79 In other words, though leaders certainly wanted to engage in ideological struggles, when it came to Islam, they preferred to defer that to the material class struggle, hoping that the latter would resolve for itself the question of Islam’s relationship to communism. As one former MKP worker told me, “Major Ishaq would often say to us ‘our struggle is not with Islam. It’s with the capitalists, the feudals, and the state.’”

Besides the MKP, the other major left-leaning (or, more accurately, left-posturing) party engaging with Islam was the PPP, however its “Islamic Socialism” was ridiculed for being neither Islamic nor socialist and only a populist appropriation of both ideologies. At a series of press conferences in South Punjab, Maulana Bhashani, for instance, noted that “during daytime, Mr. Bhutto spoke on Islam but during nighttime, he enjoyed with wine and women.” Bhashani later also questioned Bhutto’s commitment to socialism, saying landlords like him should “distribute their lands among the tillers if they really believed in socialism.”Footnote 80 Writing about Pakistan’s socialist parties of that period, including both the PPP and MKP, Iqbal Leghari concluded that many of them, despite overtures to Islam, had failed to conduct a rigorous ideological struggle over the religion. He maintained that this partly accounted for their eventual defeat, as Islam was successfully used by their opponents to delegitimize them.Footnote 81

Yet Sibghatullah did participate in such a rigorous ideological struggle over Islam, the necessity of which stemmed, not only from his own pre-existing (though under-theorized) commitment to the religion, but from the specific intensity of Islamically reasoned anti-socialism in his own village. After organizing one of his first village-level MKP meetings, Sibghatullah noted that he “had to address many people’s concerns about the party, especially the incorrect propaganda about socialism and Islam.”Footnote 82 What made this anti-socialist propaganda especially acute here was that it stemmed from three sources. First, the Makhdoom landlords reasserted their spiritual claims to bolster their landed authority, even insisting they could listen in to tenants’ private conversations as a way to stifle dissent.Footnote 83 Second, the Baloch Mazari chiefs and their supporters began “criticiz[ing] socialism … [and] prais[ing] [the Mazari tumandar] for his love of Islam.”Footnote 84And third, leaders of the Islamist Jamaat-i-Islami party would frequently tour the district, occasionally alongside their Mazari landlord allies,Footnote 85 insisting that socialism “was opposed to the teaching of the Quran and the Sunnah” and that “workers should be on guard against [any] sort of misleading propaganda made by the socialists.”Footnote 86 The party even established peasant boards across the region as fronts “to get the sympathies of the peasants.”Footnote 87

Given the intensity of this propaganda, Sibghatullah had to ideologically engage with Islam at a deeper level than was felt necessary by MKP and PPP leaders, especially if his localized class struggle was to gain momentum. Though his engagement departed from the strategic approach of both the MKP and PPP, it was nevertheless the MKP itself, especially its Maoist theory and practice, that opened the door for this. As Sibghatullah’s comrade Malik Akbar recalled: “The party conducted study circles and party schools. We read Marx, Engels, Lenin and Mao—especially his red book. Every worker had this book.… When [Sibghatullah] understood Maoist philosophy, he looked around and was no longer an ordinary Muslim. He became a Sufi and a Truth-seeker (Haqiqat-pasand).” By “look[ing] around,” the comrade was likely referring to the influence of the MKP’s Maoist, mass-oriented political practice on Sibghatullah. As part of this practice, the party regularly organized village tours across the district, tours through which, per Imtiaz Alam, Sibghatullah became more intimately acquainted with followers of Ubaidullah Sindhi. On one tour, for instance, Sibghatullah recalled with surprise an encounter with a Deobandi maulvi who, aside from “teaching children how to memorize the Quran,” was also a “politically aware person” and “help[ing] people,” and, for which reason, the “jagirdar was trying to evict him.”Footnote 88

Sibghatullah’s introduction to Maoist theory and practice thus led him to comparatively reflect on and engage with various Islams in the region. This engagement drew him to Sufism, whose universalist possibilities—which he first discovered in Karachi through the Sindh Hari Committee and then later through adherents of Ubaidullah Sindhi—facilitated its articulation with Marxism, which Sibghatullah also saw in universalist terms. Indeed, though guided by Maoism’s vernacular orientation, he was still attuned to its universalist spirit. We see his appreciation of this universal-vernacular when, for instance, he once told an MKP meeting that his movement “would hoist the red flag with the blood of jagirdars [vernacular landlords] on first May [International Workers’ Day].”Footnote 89 Though it was Maoism’s vernacular orientation that led Sibghatullah towards Sufism, it was this shared universalist element that then allowed him to equate the two: an equivalence he centered on Truth. “Like Marxists,” Malik Akbar continued, “a Sufi also seeks out Truth.” And contained within this aspiration for Truth, he elaborated, was “a love for all humanity, on feeling their pain,” since humanity was one reflection of this Truth. Though Sibghatullah did not provide a full written exposition of this equivalence—his mystical Marxism—his brief writings, especially when viewed in combination with his practice, can shed more light on it. I turn to these next.

The prose of mystical marxism

Though Sibghatullah was not a prolific writer, he did keep a diary for a few years after he joined the MKP, mostly to record meeting details.Footnote 90 A few entries, however, point to his mystical Marxism, as well as those diverse influences that led him to this theorization.

One entry that specifically evokes Sibghatullah’s politics of Truth-seeking is the draft script of a play, which centers on the efforts of a fictional landlord to clear a jungle for cultivation. The landlord entices poor pastoralists to clear the land by offering them both a monetary reward and a share of the harvest once cultivation starts, claiming that, as their pir, he cares about them and their progeny. While villagers praise the landlord’s generosity, one character in the play, simply called “the revolutionary,” insists that the landlord is actually deceiving them. “There is a Quran in [the landlord’s] hand,” he says, “but a knife hidden under his arm,” adding “the landlord’s kindness resembles the kindness we show to our goats. We feed them a lot.… But why?” To which the villagers collectively reply: “To eat its meat.” The revolutionary goes on to say that the actual intention behind both the villagers’ generosity to their goats and the landlord’s kindness to them is the same: to eventually “cut their throats with a knife.” That is, the revolutionary is trying to get the villagers to see what is truly behind the landlord’s Islam and his apparent benevolence: landlord exploitation with Islam as a ruse, whose final consequence will be the death of all villagers. Through the play, Sibghatullah was implicitly advancing the claim that revolutionary politics centered on the restoration of Truth and, relatedly, the protection of humanity (metonymically represented in the play through the villagers). By the play’s conclusion, the revolutionary’s claims about the landlord’s real intentions are borne out, as the latter refuses to keep his promise once the land is cleared, expelling the farmers and replacing them with tractors and a few hired hands. The play concludes with villagers, now aware of the landlord’s deception, joining the revolutionary and launching a land-to-the-tiller movement.

Apart from evoking a mystical commitment to Truth, the play also points to the influence of (Sufi-inflected) revolutionary Deobandism on Sibghatullah. In a dispute with the landlord’s goons, villagers justify their land claims in Islamic terms, claiming that “for Muslims, tenancy is actually makruh [an Islamically disliked act] or possibly haram [forbidden].” Right next to the play’s script is a draft of an essay, in which Sibghatullah clarifies the villagers’ reasoning and elaborates his own views on the relationship between Islam and land, citing those very (Sufi-inflected) revolutionary Deobandis he encountered through the MKP’s village tours.

He makes two main though somewhat contradictory arguments in the essay. In one set of arguments, Sibghatullah maintains that direct cultivators have a God-given right to own the land. “According to a hadith [saying of the Prophet],” he writes, “Prophet Muhammad once said, ‘that whoever gives life to dead land, that land is theirs,’” for which reason, he continues, “tenancy [is] illegitimate” (i.e., as it implies a division of ownership from labor). He substantiates this claim by citing conversations he had with “people’s (awami) imams from the Hanafi school,”Footnote 91 a reference to revolutionary Deobandis, who told him “that getting rent by giving land to someone else to cultivate is makruh.” In Sibghatullah’s view, the state also has a right to resume and redistribute uncultivated land. “Anyone who fences in land,” he writes, “can lose it after three years if they don’t cultivate it”: a claim he supports by referring to the example of the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, who appropriated and redistributed the land of a Prophet’s companion who had left it uncultivated for three years.

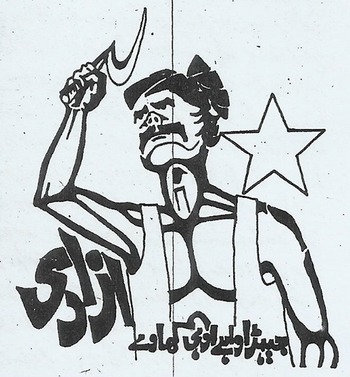

By mobilizing Hanafi law to defend the land rights of direct cultivators, the arguments of Sibghatullah and his Deobandi comrades paralleled those of earlier Muslim-led land-to-the-tiller movements, like the nineteenth-century Faraizi movement in East Bengal. But these sorts of claims actually had no basis in classical Hanafi jurisprudence: when certain strands of Hanafi jurisprudence gave a defense of property rights, Hanafi scholars typically had in mind rights of the gentry, not tenants.Footnote 92 Hanafi scholar Ashraf Ali Thanawi (d. 1943), for instance, gave fatwas insisting that tillers had no proprietary claims to the land, and that landlords had every right to collect rent and other dues.Footnote 93 Like the earlier Faraizi movement, Sibghatullah and his Deobandi comrades were subverting Hanafi orthodoxy so as to favor the property rights of tillers over gentries (image 3).

Image 3: “The one who tills shall be the one who eats”: a popular land-to-the-tiller slogan in the 1970s, one also used by the MKP. From Circular 50 (n.d.). This slogan apparently has its origins in the mantra of the seventeenth-century Sindhi and Sufi revolutionary, Shah Inayatullah: “The one who plows has the sole right to the yield.” See Nosheen Khaskhelly, Mashooq Ali Khowaja, and Asghar Raza Burfat, “Peasant Movement in Sindh: A Case Study of the Struggle of Shah Inayatullah,” Grassroots 49, 2 (2015): 44–51.

Toward the end of the essay, Sibghatullah makes a second argument that further challenges the whole idea of (landed) private property: “In a pamphlet titled ‘The nationalization of land and Islam,’Footnote 94 I have debated this topic logically and also cited fatwas from Indian ulemas [another reference to revolutionary Deobandis]—and it can be concluded that most of Pakistan’s land belongs to the public treasury. Landlords are not the lands’ owners. The Pakistani government is.”Footnote 95 Though it remains unclear from Sibghatullah’s own text as to why he shifts his argument, the contradiction also existed in the revolutionary Deobandis that Sibghatullah was inspired by. Followers of Ubaidullah Sindhi would, on the one hand, uphold the landed property claims of tillers while, on the other, demand the abolition of property entirely through nationalization. The constitution of the Mahabharat Sarwrajiya Party (All Indian People’s Republican Party), a party founded by Sindhi in 1924 and a major influence on his followers’ thought, hints at this ambivalence: while it permitted restricted smallholding property, limiting nationalization to only “big landholdings,” it also declared that “under our government, the capitalist system may have no possibility of revival.”Footnote 96 Perhaps Sindhi realized that even restricted smallholding could lead to the restoration of capitalism, for, according to his close companion, he later “advocated the abolition of private property….”Footnote 97

Another Sufi-inspired Deobandi, Maulana Bhashani, shared this ambivalence. Given that Bhashani was a major influence on MKP leaders, toured South Punjab, and forwarded similar arguments on land rights, it may not be far-fetched to suppose that he, too, shaped Sibghatullah’s theorizing. Like both Sibghatullah and Sindhi, Bhashani argued for land-to-the-tiller but later challenged the basic notion of private property, demanding that the government “nationalize all sources of income in the name of Rabbuʼl-ʻAlamin [Lord of the Universe].”Footnote 98 Both Sindhi and Bhashani’s ambivalence was akin to a policy dilemma that preoccupied the early Soviet Union and Mao’s China: whether to defend peasant smallholdings or pursue collectivization.Footnote 99 In fact, given that Bhashani and Sindhi visited China and the Soviet Union, respectively, their paradoxes, though couched in Islamic idioms, may have originated from these countries’ policy dilemmas—dilemmas that came to be expressed in Sibghatullah’s own prose.

Taken together, his prose not only reflects these diverse influences—especially the local, insurgent Islams he interacted with through the party—his writings also gesture toward his effort to reconcile them on the terrain of Truth. As the play alluded to, jagirdari obscured the Truth, presenting itself as if it benefited the villagers when in truth it would destroy them. This destruction was itself another violation of Truth, because the villagers (a metonym for humanity) were themselves a reflection of Truth. For Sibghatullah, to overturn jagirdari—either, as his essay suggests, through returning land to the tiller or abolishing landed property entirely—was to end this obscuration and instantiate in its place a set of relations that affirmed Truth (and relatedly, humanity). As his comrade Malik Akbar put it, “The Sufism of [Sibghatullah], which was about Truth and the love of humanity, found its expression in the class struggle.”

The practice of mystical marxism

More so than in his prose, it is in Sibghatullah’s political practice that we find an elaboration of his mystical Marxism. As Malik Akbar told me, “[Sibghatullah] was a practical man. He believed you needed to take knowledge forward, in practice—not just sit back, with your cigarettes and tea, and intellectualize.” As we will see, his practice of mystical Marxism had the effect of both widening and deepening the peasant movement.

According to Imtiaz Alam, one key site for Sibghatullah’s political practice was his mechanic repair shop, where he was the master/teacher (ustad) to many student-apprentices (shagirds). Sibghatullah expanded the pedagogical possibilities of the conventional master-apprentice relation, using the respect he commanded to instruct his apprentices in both craftsmanship and politics. As part of this political training, Sibghatullah asked his apprentices to compose “revolutionary essays” and “revolutionary poems,” which they then recited at the local MKP meetings.Footnote 100 Sibghatullah also asked his apprentices to preface their performances with the tawhid, the declaration of God’s unity, and to interlace their prose with verses from the Quran—practices through which Sibghatullah taught his apprentices that revolutionary politics also entailed a search for Truth. The attention Sibghatullah paid to these apprentices and their political training is evident in his diaries, where he meticulously notes who and how many showed up at the local MKP meetings.

Not only was the master-apprentice relation a medium through which to communicate his mystical Marxism, it was also itself an expression of it. For in expanding the pedagogical and political possibilities of this relation, Sibghatullah made it resemble the pir-murid relationship of Sufi orders. Called tariqah (literally: path), Sufi orders consist of pirs who guide their disciples (murids, literally “one who seeks”) on a path towards the Truth that is God. A common practice to facilitate this is zikr, the repetitive chanting of God’s names, done under the leadership of the pirs. Like pirs in Sufi orders, Sibghatullah strived for his apprentices to appreciate Truth—except with a difference. Revolutionary prose replaced the zikr, and an appreciation of Truth also entailed a commitment to abolish jagirdari. In injecting revolutionary content into traditional Sufi practices, Sibghatullah may have been inspired by the (Sufi-inflected) Deobandism of Maulana Bhashani and the “reformed mysticism” of G. M. Syed, who he had encountered, as discussed earlier, during his stay in Karachi. Syed’s protege Ibrahim Joyo, for instance, frequently organized student trips to Sindh’s local shrines, especially during the urs festivals, and elevated the historical holy men, to whom these festivals were dedicated, to the status of revolutionaries.Footnote 101 However, while Joyo rejected Sufi brotherhoods entirely—believing the pir-murid relation to be inherently marred by inequality and patronage—Sibghatullah repurposed this relation, much like Bhashani did. The latter required his disciples to affirm a belief in socialism (alongside God and the Prophet) as part of his bay’ah (oath of allegiance).Footnote 102 Perhaps both Sibghatullah and Bhashani recognized that the intimacy and sociality their relation to disciples afforded could advance revolutionary pedagogy.Footnote 103

Alongside learning about mystical Marxism, Sibghatullah’s disciples were also encouraged to return to their villages to instruct and organize others, leading to the widening of the peasant movement. Ata Muhammad Khalti (d. 2005), a peasant who joined the MKP in 1975 “under the leadership of Sufi Sibghatullah,” once described his training by a disciple of Sibghatullah’s: “He trained me politically. He was my guide. He was a very faithful person. Very truthful. Being close to him, I learnt a lot, which is why today I’ve read and written a lot and become a political activist. Many people—through chatting with him in the evening, through his friendship—got political awareness. If I hadn’t met him, then today I probably wouldn’t be who I am.”Footnote 104 As a consequence of the pedagogy of Sibghatullah and his disciples, whose transformative impact is evident in Khalti’s writing, peasants would go on to establish over forty “peasant committees,” one in each of their respective villages.Footnote 105

In addition to recruiting students and their peasant families, Sibghatullah expanded the movement by enrolling many maulvis. Though the MKP had engaged with this group as well, and indeed it was through the party that Sibghatullah became more acquainted with them, nonetheless Sibghatullah’s own later interventions were crucial to their recruitment. This was because of his “mystical Marxist” framing of the MKP, which made the party more attractive to maulvis, including followers of Ubaidullah Sindhi and even those of the Islamist Jamaat-i-Islami party, which, contrary to popular opinion, also had roots in Sufism.Footnote 106 Sibghatullah even convinced some maulvis to see the party’s work as more spiritually rewarding than conventional religious practices. During an MKP district tour, for instance, he conversed with a local maulvi, who, “after hearing about [the party program],” replied “alhamdo liʼllah [praise be to God] your party’s work is good—and the sawab [divine blessing] you will get from this is more than namaz [obligatory prayers].”Footnote 107 Like his students, Sibghatullah would invite these maulvis to local MKP meetings, meticulously taking note of their numbers and names in his diaries.Footnote 108 Eventually, the party was able to organize annual “mullah congregations.” As Imtiaz Alam recalled: “After the party connected with Sibghatullah, we would also hold annual Eid Milad un-Nabi celebrations with mullahs coming into congregation, joining hands against feudalism. They delivered fatwas against feudalism, quoting the Quran and hadith. These were peasant mullahs, often from the Ubaidullah Sindhi tradition, and over a thousand would come.”

Sibghatullah supported these peasant mullahs as they built their own mosques independent from those patronized by the Makhdooms, and at which, a childhood friend recalled, Sibghatullah would also deliver anti-landlord sermons (khutbas). The Makhdoom landlord Ghulam Miran Shah tore down five of these mosques precisely because of their insurrectionary character, an incident that provoked peasants to proclaim: “The jagirdar’s injustice has extended from the peasants’ home to the house of God, but those days aren’t far off when, with the power of God, peasants will destroy the jagirdar’s home.”Footnote 109

Alongside the widening of the movement to include apprentices, their families, and the peasant mullahs, was a deepening of it. As the dispute over the mosques suggests, Sibghatullah’s theory and practice of mystical Marxism had begun to undermine hegemonic Islam, especially claims about its incompatibility with socialism/communism. Other incidents illustrate this further. In 1976, as the peasant movement was in full swing, the Makhdoom landlord had a grandson whom he wanted to name Sibghatullah (whose literal translation is “color of God”), and he tried to get Sibghatullah to change his name. This conflict over who was entitled to use this name was, in essence, a dispute over competing visions of Islam, with many peasants in the end siding with Sibghatullah, insisting that “in our Sufi, ‘the color of God’ is pure.”Footnote 110

This breach between the Sufi Islam of the Makhdooms and the mystical Marxism of Sibghatullah widened still further when the Makhdooms enlisted the support of Sindh’s Pir Pagaro, otherwise a widely admired Sufi pir in the region, in their attempt to suppress the peasant movement. According to Imtiaz Alam, the Pir Pagaro, with whom the Makhdoom had ties through marriage,Footnote 111 sent some four hundred of his armed disciples, the Hurs, to suppress the peasant insurrection.Footnote 112 Not only did Sibghatullah and his supporters successfully fight off the attack, but in the process, peasants gained further proof of the exploitative and indeed violent nature of elite-peddled Sufism.

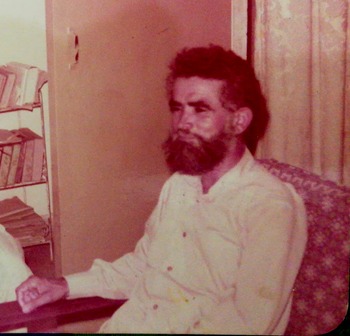

A result of the widening and deepening of the peasant movement was a radicalization of its demands. Whereas before peasants had demanded an end to their expulsions, security of tenure, and fairer, more transparent sharecropping, by the mid-1970s they occupied land and refused to sharecrop at all. “The struggle in [Sibghatullah’s village],” Imtiaz Alam wrote at the time, “is one of the most advanced struggles [in Punjab], where peasants have completely stopped sharecropping and also everything else—and have made the peasant committees strong.”Footnote 113 Undergirding these tenant refusals and their creation of alternative peasant institutions was a growing belief amongst them that jagirdari was essentially exploitative, and that it could not be reformed and had to be abolished. What furthered the popularity of this belief was the alignment between the landlords’ practices and Sibghatullah’s claims about them. That is, as tenants witnessed landlords reject even their modest, reformist demands and coercively suppress their movement—even deploying notable Sufi institutions like the Pir Pagaro to do so—they became increasingly convinced of Sibghatullah’s “mystical Marxist” claim that jagirdari was, in essence, exploitative. As Malik Akbar put it, “Tenants came to realize the prevailing system—the fact that some have land and with it, rule over others who don’t—was what the landlords had created, not God, and was in fact against God’s decision.” With that realization, Malik Akbar continued, “The tenant movement entered another stage, where they now thought it was possible to overturn jagirdari.” Rather than a more reformed, less exploitative jagirdari, tenants now demanded its abolition: “The region’s peasants have now stood up against jagirdari,” Sibghatullah reported at the time, “and are uniting under the leadership of the MKP” (image 4).Footnote 114

Image 4: Sibghatullah toward the end of his MKP days, ca. the late 1970s. Courtesy of Qayum Mazari.

Tribe trouble

This radical turn in the movement led to an even more severe crackdown. After tenants refused to sharecrop, both Baloch and Makhdoom landlords besieged the villages, forcibly retrieved the crop, and evicted some tenant families and replaced them with hired labor. Many families were injured,Footnote 115 and some peasant leaders were murdered (image 5).Footnote 116 When, in 1977, General Zia ul-Haq (d. 1988) toppled Bhutto’s regime in a military coup, the offensive against progressive movements only accelerated. State repression, alongside selective concessions to peasantsFootnote 117 and internal divisions within the MKP’s leadership over revolutionary strategy,Footnote 118 led to the party’s fragmentation and then collapse. Though Sibghatullah was able to continue his political activities for a few years, and was even elected village chairman (nazim), defeating the Mazari landlord’s candidate for the first time, he too was eventually targeted by the military regime and forced to flee to Karachi.

Image 5: Obituary for Qadir Baksh, Sibghatullah’s comrade who was killed by a Makhdoom landlord. Source: Circular, 75 (July 1976): 24.

When the military regime had collapsed and he returned, Sibghatullah reinitiated his political activities. In 1991 he formed the Anjuman Banu Mazari (the Banu Mazari Association), which incorporated his combination of Mao-inflected Marxism and Sufism—his mystical Marxism—in several ways.

For one, the organization’s ostensibly “tribal” form—it was named after Sibghatullah’s clan (Banu Mazari) and aimed to “organize and unite [it]”Footnote 119—expressed his continuing sensitivity to the vernacular. During the 1980s, the language of class had become less salient as an identity for mobilization, and many progressives in South Punjab, as elsewhere in the country, had increasingly turned to ethnicity.Footnote 120 Apart from General Zia’s country-wide repression of the left, what contributed to this turn in South Punjab specifically was agrarian transformations on the landed estates. Given the immense size of their landholdings,Footnote 121 Makhdoom and Baloch landlords, unlike landlords elsewhere, were less able to evict their tenants in response to Bhutto’s land reforms and the 1970s tenant movement, and instead resorted to a combination of capital-intensive tenant and wage-labor based agriculture.Footnote 122 But by the early 1990s, they, like landlords across South Punjab and elsewhere,Footnote 123 began to introduce what was essentially a system of contract farming (mutaydari or mustajiri). Not only were contracts (mutas or mustajiri) annually renewed, but farmers—now called “contractors” (mutaydars/mustajireen) rather than “tenants” (muzayray)—lost any protections they had enjoyed under the Punjab Tenancy Act of 1887. The precarity of tenure, combined with the collapse of the tenant category itself, meant that adopting the methods and class categories of the 1970s would be to ignore these local changes and thus be a strategic mistake. By turning to tribe, Sibghatullah aimed to make class struggle more locally legible or vernacularly sensitive. “He gave tribal politics a revolutionary direction,” Malik Akbar told me. “The language may have shifted, but at heart he was still a communist. By making this organization, Sibghatullah was still challenging tribal chiefs.”

Apart from the vernacular orientation, it was this commitment to challenging landed chiefs, and do so by creating a united front, that bore the imprint of Sibghatullah’s mystical Marxism. “There are people outside the Banu Mazari who are intelligent and progressive,” he wrote in the organization’s manifesto, and “[we] will try to form a united front (muttahida mahaz) with [them], on an equal footing.”Footnote 124 Sibghatullah’s call for intra- and inter-tribal unity, forged on the basis of equality, evoked both his Sufi commitment to universal humanity and the Leninist-Maoist practice of United Frontism. The mechanisms through which he aimed to create and maintain this unity also suggested this combined inheritance. First, the front would remain “apolitical, areligious,”Footnote 125 by which he meant that it would not discriminate on the basis of party or religious affiliation but be mass-oriented: an orientation that evoked both the MKP’s politics of the masses, as well as Sufism’s emphasis on humanity. Second, the front would only politically act on the basis of facts, not hearsay, conducting “census[es]”Footnote 126 for this purpose, a stance that reflected both the MKP’s Maoist commitment to a politics driven by “social and economic investigation”Footnote 127 and Sufism’s aspiration for Truth. Lastly, it would also abide by internal operating procedures that promoted intra- and inter-tribal unity. “There will be complete democracy in the organization,” and “no ban on criticism and self-criticism,” but, once a democratic decision is made, “every member will be bound to [it].”Footnote 128 These procedures paralleled the MKP’s practices, especially the emphasis on criticism/self-criticism, the “hallmark distinguishing [a Maoist] Party from all other parties,”Footnote 129 under a democratic centralism. However, their intention to uphold cross-tribal unity also reflected a Sufi commitment to humanity.

By creating and upholding this united front, Sibghatullah sought to undermine the very tribal and clan-based distinctions upon which chiefly landed authority rested. As his childhood friend Master Sajid recalled, “Sibghatullah’s goal was to make the peasants one tribe, the landlords another.”

In the organization’s first political campaign, we see the further elaboration of this tribe-centered confrontation with landlords and, more broadly, Sibghatullah’s mystical Marxism. The campaign confronted patriarchal control and gendered oppression, which Sibghatullah believed co-constituted landlord power, thus subordinating men and women alike and violating humanity. Land and women (zameen and zan) were central to most tribal disputes in South Punjab because, as in other parts of the Muslim world,Footnote 130 these were considered constitutive of a tribe’s integrity and honor and could be subject to violations by others. Women’s sexuality was one site of potential transgression, whereby any accusation of extra-marital sex led to women being labelled kali (dishonored) and punished through murder (as happened to Sibghatullah’s first wife), being sold into slavery or being exchanged (wata-sata), all in accordance with the kali qanun (“honor” codes). The kali qanun was adjudicated through a jirga (council), headed by a chiefly landlord, who legitimized the application of these codes in Islamic terms. To confront these codes, as Sibghatullah openly did, was in effect to challenge not only elitist Islam, landed power, and tribal authority, but also gender distinctions. The campaign developed Sibghatullah’s mystical Marxism, in that, much like the thirteenth-century Sufi mystic Ibn al-Arabi,Footnote 131 his commitment to humanity led him to argue for fundamental equality between all human beings, regardless of gender.

Alongside humanity, Sibghatullah’s critique of the kali qanun was also driven by a commitment to Truth, which meant confronting its use anywhere, including among his fellow peasants. He condemned how, “under the cover of the kali qanun,” men committed all sorts of violence against women: from murdering disliked wives in order to marry another to punishing disobedient daughters.Footnote 132 He condemned the fact that women did not even “have a right to provide an explanation or have an investigation conducted,” a commitment to investigation that reveals the imprint of both the MKP and his own Truth-seeking mysticism. He went on to say that these practices, despite what their supporters say, had no place in Islam, but belonged instead to the “zamana-e-jahiliat” (“the age of ignorance,” a reference to pre-Islamic Arabia).Footnote 133 In opposing these honor codes, and thereby challenging both landed authority and patriarchy, Sibghatullah ultimately aimed to restore Truth.

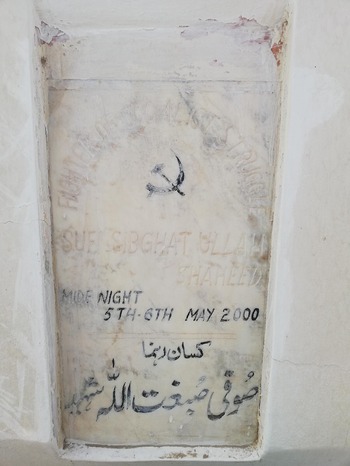

Because of how it upset landed power, tribal identities, and gender relations, confronting the kali qanun was a risky endeavor, one that Sibghatullah paid for with his life. In the mid-1990s, his organization defended a Banu Mazari woman accused of being kali by her father-in-law (who was also Sibghatullah’s relative).Footnote 134 After investigating the accusation and discovering no evidence for it, they helped the woman hide. As a result, Sibghatullah faced pressure from his relative, who wanted the woman back in order to murder her, but also from the petty chief of the Banu Mazari clan, Azeem Khan. One morning in 2000, as Sibghatullah was shepherding his goats near his house, a man axed him to death. He was only fifty-six. In the village, it was widely believed that Azeem Khan and certain members of the Mazari chief’s family were behind the murder. What appears to have angered them was the fact that Sibghatullah’s campaign, in confronting the kali qanun and patriarchal control—and doing so in the very Islamic register they themselves used to uphold these codes—seriously challenged their tribal and landed authority (image 6).

Image 6: Sibghatullah’s tombstone in Bangla Icha. Alluding to his multiple influences, the epitaph describes him as a “Sufi,” a “peasant leader,” and a “fighter of socialist struggle.” Author’s photo.

Conclusion

In his founding statement on subaltern studies, historian Ranajit Guha argued that India’s political elites, including implicitly its communist parties, had failed to become hegemonic, to establish consent for their authority, resulting in what he would later call their “dominance without hegemony.”Footnote 135 He attributed communism’s inability to establish hegemony amongst the peasant masses, in part, to their attitude toward religion. For it was Indian communism’s dismissal of peasant religious beliefs, an inability to acknowledge their disruptive potential,Footnote 136 that partly accounted for their “historic failure”Footnote 137 to lead the peasant masses. Communist parties continue to dismiss the emancipatory possibilities of religion, in India as well as in Pakistan.Footnote 138

The relationship of the MKP to peasant subalterns like Sibghatullah, however, reveals an alternative relationship between communism and the peasantry, one where the former was less dismissive of the religious beliefs of the latter. Unlike many communists in the region, MKP leaders, in part because of their distinct Maoist appreciation for the vernacular, did see the radical possibilities of religion. And even though their relationship to Islam remained within strategic registers, their openness to it encouraged subaltern peasants like Sibghatullah to theorize their own relationship to Islam and communism. Rather than ignoring the transformative possibilities of beliefs conventionally exterior to it, communism, at least as practiced by MKP leaders, allowed the pursuit of these possibilities.

It was Sibghatullah’s introduction to the party’s Maoist theory and practice that led to his comparative engagement with Islam as well. Specifically important was Maoism’s politics of the “mass line” and philosophy on practice, which entailed a deep immersion in the beliefs and practices of the masses in order to generate a vernacular-driven communist universalism. That steered Sibghatullah toward circulating insurgent Sufisms and a comparative inquiry into their relationship with Marxism. Driven to Sufism by Maoism’s vernacular orientation, Sibghatullah discovered shared universalist elements that then enabled him to equate the two: an equivalence he centered on a joint commitment to Truth. Contra Guha, who saw religious consciousness as a precursor to a secular, revolutionary class one, Sibghatullah fathomed a religious consciousness that did not simply mediate for revolutionary class consciousness but was made coincidental with it on the terrain of Truth.

Sibghatullah also expressed his mystical Marxism in political practice, as he transformed his apprentices into revolutionary Sufi disciples, recruited Sufi-inflected maulvis, organized annual “mullah congregations,” built alternative insurgent mosques, and even later challenged the tribal landlords’ patriarchal “honor” codes. Though his theory and practice of mystical Marxism led to both a widening and deepening of the MKP-led peasant movement, especially as he undermined landlordism’s hegemony over Islam, it failed in the end owing to the fragmentation of the party and the wider anti-left state repression begun by Bhutto and continued by General Zia. Nonetheless, his mystical Marxism left its traces in successors like Allah Baksh, traces which, in pointing to an unrealized past, evoke possibilities for a future in which religious and secular thought, widely polarized in today’s world, may be united for a practice of liberation.