Accourez, contemplez ces ruines affreuses.

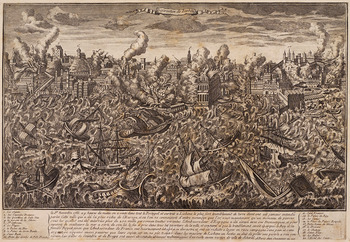

———VoltaireThe ruin has long been viewed as a remnant of a lost vitality or wholeness that prompts either forgetting or nostalgia––reactions that avoid confronting the ruin for what it is as a site of impermanency and fragility, of suffering and death, as Voltaire insisted in the wake of the Lisbon earthquake of 1755. Whether the source of ruination might be described as natural or historic, whether the process of destruction might have unfolded slowly or erupted suddenly, the ruin stands as a memento mori that reveals the vulnerability of human creations no matter how monumental they might be: the elegant, imperial city of Lisbon was rendered into a chaotic site of crashing waves, crumbling stone, and smoke-filled skies in a matter of seconds. “The earthquake of Lisbon sufficed to cure Voltaire of the theodicy of Leibniz,” Theodor W. Adorno wrote nearly two centuries later,Footnote 1 which is to say that the city's ruination undermined the Enlightenment's exuberant aspiration to yoke nature under human control. Equally, if not more destructive to Enlightenment optimism was the ruination produced by Hitler's genocidal campaign against the Jews, a ruination which, as Adorno famously argued with Max Horkheimer, emerged partly from the Enlightenment's striving to master nature.Footnote 2

Figure 1 A 1775 copper engraving of Lisbon. Courtesy of Museu de Lisboa.

After 1945, Europeans responded to the ruination produced by Nazism in various ways. In the early postwar years, the prevailing response was to turn away from the death caused by the Holocaust, to clear away and forget Jewish ruins amidst the fervent embrace of urban modernism and optimistic notions of progress.Footnote 3 Traveling across West and East Germany in the early 1960s, Amos Elon wrote, “The resurrected cities—brand new, clean, sober, infinitely monotonous—stand on the former ruins.”Footnote 4 And yet, as ascendant as this modernist impulse to bury past ruins was after 1945, it came into question by the late 1970s, when urban modernism was critiqued as ruinous to the historical character and particularity of the city.Footnote 5 Stimulated partly by these critiques, interest in the few Jewish ruins that still could be found began to emerge across parts of the European continent. This interest varied widely from nostalgic efforts to “recover” the prewar Jewish past to searing efforts to reflect on the death and destruction of the Holocaust.

In this essay, I would like to discuss this shifting history of encounters with Jewish ruins by focusing first on the early postwar forgetting of Jewish ruins during the height of urban modernism, and then on efforts since the late 1970s to reflect on the ruination of prewar Jewish life. To sharpen my focus, I will examine two examples from Central Europe that I consider to be paradigmatic of each respective historical period: the attempt by architect Bohdan Lachert to memorialize the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto in the early 1950s and that by Daniel Libeskind in the late 1980s to create a metaphorical ruin in Berlin so as to express the death and destruction of the Holocaust. What unites these two temporally and spatially different examples is the intention of both artists to reflect on death, suffering, and absence.

Lachert's Warsaw project has received relatively little scholarly attention, while Libeskind's Berlin project has received so much that readers may reasonably wonder if there is anything new to say about it.Footnote 6 Yet one aspect of Libeskind's project deserves more attention than it has gotten, namely the ambition and ambiguity of Libeskind's effort to create a building of fragments that fail to come together into a whole.Footnote 7 He sought to create a monument of ruination that resists the modernist impulse to turn away from suffering and destruction. He wanted to create a ruīna—Latin for “collapse”—in a fully constructed building designed to tell a historical narrative that, as such, is inherently holistic.Footnote 8 This is a project of considerable tension that prompts several questions: Is this effort coherent? How can a new building represent ruination and absence? And how, in the particular case of Libeskind's project, does the building's purpose as a history museum match its architectural attempt to represent what has been lost? How does the museum's historical narrative of continuity match his interest in expressing rupture? In raising these questions, my purpose is not to cast doubt on the “success” of Libeskind's project, but rather to explore the challenge he faced in striving to represent absence within the context of his building's pedagogical, historical purpose.

In the end, the two examples discussed here, while coming from different historical contexts, suggest two striking affinities that transcend their otherwise obvious differences. The first may be expressed in terms of a tension that courses through both cases: between revealing and concealing the ruin as a site of suffering, death, and absence. The concealing side of this dyad may initially seem most overt in the case of Warsaw, where the history of the ghetto was forgotten almost entirely with the construction of new buildings on top of it in the early 1950s.Footnote 9 Yet the Warsaw case is complicated. Bohdan Lachert's architectural attempt to represent the absence of Jewish life, while ultimately unsuccessful, was nevertheless significant and indeed anticipates to some extent Libeskind's project to represent the ruination of the Holocaust. The Berlin case is complicated as well: Libeskind's aspiration to represent ruination in architecture is hindered, if not concealed, by precisely the impulse to represent what eludes representation, and by the linear historical narrative that his building contains. In short, the tension of moving both toward and away from suffering and ruination courses through both cases.

The second affinity lies in what is at stake in these projects for both architects. Lachert and Libeskind both expressed an interest in creating architectural projects that would stimulate public reflection on ruination so as to move beyond the traditional form of the monument. Conventionally, the monument has long sought to recuperate and immortalize what has passed away. It has been oriented toward salvation, understood as freedom from the pure ephemerality of time and the recovery of the past from oblivion. The conventional monument seeks to establish a sense of permanency. This orientation toward permanency smooths over or entirely forgets the ruination and rupture of history. In contrast, Lachert and Libeskind seek to perpetuate a kind of non-salvific memory that confronts ruination, death, and absence. At stake for them is promoting a form of remembrance that mourns the absence of prewar Jewish life and thereby avoids the salvific impulse to recuperate history so as to overcome the pure transience of time. Hence, both of these cases involve creative reactions to ruination that differ considerably from the dominant tendencies of their times, tendencies that have coursed through European history since the ancient period.Footnote 10 In this respect, Lachert and Libeskind wittingly stood outside the shared, collective reactions to ruination that shaped their respective eras and the traditions in which they worked as artists.Footnote 11

The essay has three parts. The first argues that Lachert's unconventional attempt to reflect on the absence of Warsaw Jewry fell victim to the impulse to harness the wartime past for the political needs of the present, specifically for the Communist Party's campaign to ground its authority in a historical narrative of national rebirth crafted both literally and metaphorically through the rebuilding of Poland's capital. The essay's second part emphasizes the ambition of Libeskind's effort to represent absence, and examines the constraints inherent in the content and form of his project. A final section brings these cases together as novel, if circumscribed attempts to reflect on absence and ruination in the postwar period.

THE RUINS OF THE WARSAW GHETTO

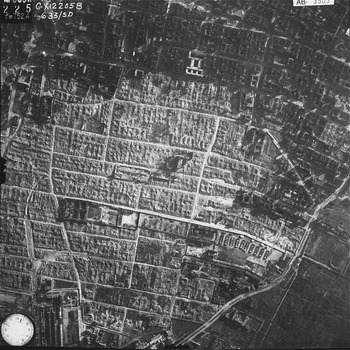

Since 2010, the video Miasto Ruin (City of ruins) has been showing in the Warsaw Rising Museum. It seeks to recapture the death and destruction of Warsaw in 1945.Footnote 12 Created from 1,600 historical pictures, it provides a “fly over” of Warsaw's charred landscape, documenting the near total destruction of the city's old town before then coming to a field of crushed stone, an area that stands out, even in postwar Warsaw, for its ruination.Footnote 13 Mounds of shattered stone, twisted beams, broken glass—this is the space of the former Warsaw ghetto, the space that had once comprised the main area of Jewish life in the city.Footnote 14 In 1945, the area, known as Muranów, existed only as one gigantic ruin. “Around us, over a wide area, there was nothing but powdered rubble—ruins, ruins, ruins,” one Jewish survivor observed. “It was impossible to believe that destruction could be so complete.”Footnote 15 A stunning aerial photo taken of the ghetto in 1945 shows an area flattened almost entirely.

If one visits Warsaw today, one will find almost no artifacts of the area's wartime destruction. Nearly all the physical traces of the catastrophe of the Warsaw ghetto have either been cleared away or concealed by new buildings. This erasure may not surprise urban historians, since cities have been reconstructed anew many times before, and Warsaw's urban planners clearly had to rebuild their city in some manner.Footnote 16 Even so, the sheer extent of the postwar erasure of Muranów is striking, a point that Jewish visitors noted. In 1958–1959, Abraham Michael Rosenthal of the New York Times, whose international reporting garnered him a Pulitzer Prize, lived in Warsaw, where he occasionally visited the former space of the ghetto. On the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the ghetto uprising he recalled his first visit to Muranów. Looking at the ghetto space, with his wife and a young Jewish writer living in Warsaw, he wrote: “It was early in the morning; about 2 or 3 o'clock, and he took us out of the old part of town into a terrible emptiness. I said: ‘What is it?’ and he said it was the ghetto. There were some apartment buildings on the edges of the emptiness and they seemed awkward and strange, standing on what looked like mounds. I said, ‘Why are the built like that?’ and he said they were built on the remains of buildings and bodies and rubble of the ghetto, because it was cheaper that way.”Footnote 17

Figure 2 Aerial view of the destroyed Warsaw Ghetto on 16 May 1943. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The views or opinions expressed in this article and the context in which the image is used do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of, nor imply approval or endorsement by, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Rosenthal provides an image of the new Muranów that was taking form in the early 1950s. The rebuilding of the district stemmed from plans for Warsaw's rebuilding that emerged immediately after the war and that came from a group of leftwing, avant-garde architects who had formed the backbone of interwar Poland's small, yet active modernist movement. Centered mainly at the Warsaw Polytechnic School of Architecture, the modernist milieu, which included architects such as Roman Piotrowski, Helena and Szymon Syrkus, Barbara and Stanisław Brukalski, Bohdan Lachert, and Józef Szanajca, followed international developments in Germany, France, and the United States and worked to apply modernist, functional designs to Warsaw's notoriously chaotic, cramped urban layout. Publishing articles in experimental journals such as Blok and Praesens, these architects focused mostly on providing solutions to housing and became involved in international discussions about modern architecture through meetings such as the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM).Footnote 18 During the Nazi occupation, they joined together to form the underground Architecture and Town-Planning Studio (Pracownia Architektoniczno-Urbanistyczna, or PAU) that worked on plans for Warsaw's eventual reconstruction.

In 1945, Poland's Communist provisional government created the Office for the Rebuilding of the Capital (Biuro Odbudowy Stolicy, BOS) that oversaw Warsaw's reconstruction. Filling the ranks of BOS, Poland's interwar architects now had the unprecedented opportunity to create in practice what before they had only imagined on paper: a modern, functional Warsaw of green areas, socially progressive housing complexes, and a sensible transportation system.Footnote 19 Created for a maximum population of 1.2 million, the first plan for Warsaw organized the capital into functional parts of housing, industry, leisure, green space, and areas for work.Footnote 20 The design was received enthusiastically in Poland, and then warmly in the United States during a tour entitled “Warsaw Lives Again.”Footnote 21

In 1949, Poland's Communist Party announced the “Six-Year Plan for the Reconstruction of Warsaw” that guided the bulk of the capital's rebuilding.Footnote 22 The plan kept with the basic modernist, functional design intended to alleviate the city's cramped layout, but departed from earlier proposals in several key ways. Although socialist realism, with its monumental, ornamental, and representative architecture, had yet to fully shape the rebuilding of Warsaw, the ideological basis for building a “socialist city” became much more clearly articulated in the Six-Year Plan. The plan stressed two main elements of the socialist Warsaw: the development of industrial production as befitting a “city of workers,” and the building of new housing complexes that transcended the cramped, poorly accommodated tenement houses of the capitalist, bourgeois past, which had deprived the workers of “greenery, recreation grounds, and cultural facilities.”Footnote 23

Muranów was an important area in the center of the city for the regime's socialist aspirations. From its earliest plans, BOS decided to turn Muranów into a large housing complex as the cornerstone of Warsaw's transformation into a socialist city.Footnote 24 Because Muranów was a cramped tenement area, it became one of the main areas for implementing the new socialist conception of housing that purported to transcend the limitations of capitalism. However, Muranów presented a particularly difficult task for BOS's architects, who had to deal with not only the enormous amount of rubble, especially in the northern part of the district which had been flattened completely, but also the history of the space itself. Most urban planners initially paid little or no attention to the area's history. The first plans for the district, published in 1946–1947, focused on the details of the housing complex to be built there.Footnote 25

Then, in 1948–1949, a new architect, Bohdan Lachert, took over the project and proved to be more interested in reflecting on the area's history than any other designer that worked on it before or after him.Footnote 26 Although Lachert set out to transform Muranów into a new housing complex of square, functional, and unadorned apartment buildings, he sought to at the same time express the particular history of the space upon which his buildings were to be erected. This was no easy task: how could one possibly memorialize in a housing complex? Lachert's answer—albeit subtle, if not oblique––was to leave the front of his buildings un-stuccoed and use a rusty red brick, with the intention of capturing the ghetto's somberness. As he put it, “The history of the great victory of the nation paid for through a sea of human blood, poured out for the sake of social progress and national liberation, will be commemorated in the Muranów project.”Footnote 27

Figure 3 Few up-close, color photos of Lachert's red-brick façade exist. However, the social-realist plaster of the 1950s is now peeling off. Photo by Michael Meng 2014.

Lachert saw his project as reinforcing the purpose of the Warsaw Ghetto Monument, which had just been erected in 1948, slightly to the north of his housing complex. The Central Committee of Jews, the leading Jewish organization in postwar Poland, had selected for the monument a design by the Polish-Jewish sculptor Natan Rapoport. It heroically commemorated the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, depicting on its western side proletarian-looking figures brandishing arms as they seem to jump out from the granite in which they are carved.Footnote 28 Lachert not only praised Rapoport's design but also insisted that it affirmed the memorial intentions of his housing complex:

The grim atmosphere of this great mausoleum, erected among a cemetery of ruins, soaked with the blood of the Jewish nation, should remain, as new life comes into existence. The architectural project, carried out in the rebuilding of Muranów, should not reduce these artistic elements, which the sculptor Rapoport created through a magnificent sculpture of bronze and granite.… The ruins, in the largest possible amount, should remain in place, remembering the days of terror and resistance, constituting the ground on which a new city, a new life will be raised.Footnote 29

Figure 4 The Warsaw Ghetto Memorial. Photo by Michael Meng 2007.

Lachert's intent was to incorporate the past into the Communist building of the future, an ambition with no precedent in this area of Warsaw. In effect, he envisioned his housing project as a monument to the dead that would be a burden on the future: the past would play a living role in the new Warsaw as a reminder of human suffering and as the foundation, so to speak, for building a new future beyond the violence and hatred of the past. His project issued in a bold call to reflect on suffering, death, and absence in early postwar Poland. This was precisely when the Communist regime was aiming to create a much different future largely freed from or even oblivious to suffering, and the past in general, aside from its highly selective and overtly salvific effort to recuperate the “Polish” past for the purpose of legitimizing its power. Seeking to ground Communism in Polish history, the regime depicted Warsaw as a “martyr city” that was reemerging from near death under the benevolent and progressive rule of Communism. The central space appropriated for this narrative was Warsaw's heavily destroyed old town (stare miasto). In the opening essay to the first issue of Stolica, the illustrated weekly published by BOS, the task of resurrecting Warsaw's old town was framed as a sacrosanct act of national recovery. Surrounded by prewar pictures of Warsaw's Royal Castle, medieval Cathedral, and market square, the article suggested that the old town had to be reconstructed to demonstrate the immortality of the Polish nation:

Warsaw has her own eternal, living beauty. She has not lost it even now when many of her most beautiful monuments were totally exterminated. Whether it is the area of the Royal Castle, lying in a shapeless pile of ruins, the beautiful gothic cathedral, lying in one large heap of rubble, or the old-town market square where only three tenement houses remained in small fragments—this tragic spell rivets the people today and draws them to the ruins.… There was no dispute, there were no two ways about it among Polish society that monuments of cultural and architectural value in Warsaw—from the Royal Castle to the Cathedral to the Old Town—must be resurrected.… The resurrected walls of the old town will not be a lifeless creation, but will stand as a living link connecting the past to the present and the future.… We are not a nation whose history began in January 1945 at the moment when the barbarians from the west were chased away. Our history dates back to the tenth century of the Christian era.Footnote 30

Drawing on the deeply rooted notion of Poland as the “Christ among Nations”—a country crucified for the sins of the world that would return to rescue humanity—this article creates a basic salvation narrative by casting Warsaw as a martyr city that will overcome death. Warsaw's old town is not to be rebuilt but “resurrected” (wskrzesić) from ruination.

This salvific recovery of the past was starkly different from Lachert's reflection on the somberness of the ghetto space. He expressed no interest in resurrecting the prewar Jewish past. Rather, his architectural project attempted to represent the absence and ruination of this past. Whereas the reconstruction of the old town aspired to recover a lost past and overcome ruination, Lachert's project sought to mourn that past as ineluctably lost. Challenging the postwar propensity to flee from the death and destruction of history, Lachert's project tried to create, within the parameters available to him, a different relationship to the past, a different kind of memory, which was expressly not salvific in the metaphysical sense of striving to recuperate what has been lost.Footnote 31 On the contrary, his architectural project intended to turn toward the suffering, death, and ruination of the ghetto.

The novelty of Lachert's project vis-à-vis the stare miasto deserves emphasis. The reconstruction of the old town was oriented towards affirming the indestructability of the Polish nation. It sought to deny the Nazi attempt to eliminate the history and culture of Poland through a monumental display of recovery and reconstruction. If Lachert's project obviously contributed to Warsaw's recovery, it was oriented toward a monumental display of fragility and suffering rather than indestructibility.

By 1949–1950, however, Lachert's novel project had come to an end. The modernist principles that had shaped it and much of Warsaw's reconstruction up to that point were rejected for the new architectural style—socialist realism—spreading across the Soviet bloc with the beginning of Stalinism. Originating in early 1930s Moscow, socialist realist architecture documented the historic triumph of Communism over capitalism by showcasing the historic movement from the dark, dirty, cramped, and chaotic capitalist city to the light, clean, spacious, and orderly socialist city.Footnote 32 Its grandiose, ornamental style was imported into Eastern Europe in the late 1940s and early 1950s. When it arrived, Lachert's plans were criticized for their modernist expression and alleged gloomy representation of the ghetto space.Footnote 33 The fallout was clear, and Lachert's buildings were stuccoed and small designs were painted on their white surfaces to make them conform to the formulaic principles of socialist realism. No deviation from the governing norm of socialist realism could be permitted, and Lachert's architectural attempt to express the ruination and absence of Warsaw Jewry was rejected.

Muranów was now definitively to be a space of the socialist future.Footnote 34 The district was made to conform to the salvific narrative of Warsaw rising from ruination under the benign rule of Communism and, thus, the wartime history of Muranów was increasingly erased. To be sure, this erasure of the Holocaust was not completely hegemonic; the removal of the ghetto rubble hardly meant that individuals could not remember the area's traumatic history. Some Jews living in Muranów certainly nourished memories of the Holocaust.Footnote 35 Even so, the new housing complex involved a significant erasure of the past in public, collective memory, not least because humans powerfully express their collective memories in the ordering, marking, and commemoration of public spaces—what is and is not preserved matters. As Maurice Halbwachs suggests, “Since our impressions rush by, one after another, and leave nothing behind in our mind, we can understand how we can recapture the past only by understanding how it is, in effect, preserved by our physical surroundings.”Footnote 36

So what was ultimately preserved for future generations in the socialist rebuilding of Muranów? It was the socialist narrative of rebirth from the devastation of Nazism. The new Muranów celebrated in the urban landscape the new beginning that Communism sought to commence in Poland, one that turned away from the suffering and death of the past to the new future of material prosperity and progress. According to press accounts, the district's transformation represented the movement away from the darkness of the past to the light of the Communist future. “New, bright houses grow on the ruins of the ghetto; a new life grows, which prevails over destruction and mass extermination. These houses and the forest of scaffoldings that are rising up throughout all of Warsaw are evidence to the constantly growing power of peace and socialism.”Footnote 37

The socialist rebuilding of Muranów turned away from the mass violence of the past. It reflected the desire, at least on the part of the Communist regime, to fill in the emptiness and absence of the ghetto space with the promise of the new Communist future. As President Bolesław Bierut put it in the Six-Year Plan, the new district would mark a bold departure from the past: “This year, on the ruins of the former ghetto, the Workers's Housing Society has started building Muranów which is to be the largest settlement in Warsaw.”Footnote 38 Perhaps the most powerful illustration of this turn away from the death and destruction of the ghetto can be seen through photos of the new district. One such photo captures a view of the new socialist district in 1959 with the stuccoing fully completed on the outside of Lachert's apartment buildings. As a space of the socialist future, the new district was now a bright and cheerful place that affirmed Warsaw's resurrection from death and ruination.

Figure 5 Postwar Muranów in 1959. Courtesy of Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe.

Although one cannot say definitively that this transformation of Muranów reflected a deliberate effort on the part of the Communist regime to forget the city's Jewish past, there is enough evidence to suggest that it was.Footnote 39 The regime rebuilt Warsaw as an ethnically and culturally Polish capital. The great symbolic meaning it invested in the rebuilding effort told a story about the revival of the Polish nation after war and genocide. This narrative could most certainly have included Jews; exclusive imaginations of the Polish nation are historically contingent and need not necessarily exclude Jews.Footnote 40 Yet, after the war, the regime generally embraced an ethnically and cultural exclusive imagination of the nation, as clearly evident in its reconstruction of Warsaw: whereas the ruins of Warsaw's stare miasto were venerated as sacred fragments of the Polish nation that had to be salvaged, the rubble of the ghetto was viewed as debris that could be cleared away for the building of the new future. Most strikingly, there were very few efforts by the regime to mourn the loss of Warsaw as a “Jewish metropolis.” While Jews who returned to Warsaw immediately after the war saw Muranów for what it was—a massive space of death—the regime did not.Footnote 41 It was not until much later, and above all after the collapse of Communism, that efforts emerged again to reflect on Warsaw's Jewish past and the mass murder of its Jewish population during World War II.Footnote 42

THE BERLIN JEWISH MUSEUM AS A RUIN

The ultimate forgetting of ruination in early postwar Warsaw can hardly be characterized as unique to Poland. It suggests one of two general European reactions to the Holocaust.Footnote 43 The other reaction that I want to discuss involves the desire to represent absence and ruination through architecture. Though anticipated by Lachert's project, this desire emerged most visibly by the late 1980s and reflected two broad cultural and intellectual developments of the late postwar period: first, the growing awareness of the Holocaust in the public sphere in Western Europe and the United States,Footnote 44 and second, the general tendency in continental thought to reflect on the ruptures and ruins of modernity in contradistinction to conventional historical narratives that either simply ignore the violence and suffering of history or seek to smooth it over through redemptive narratives of progress.Footnote 45 This growing interest in the ruins of history was distinctly political. Just as Lachert's effort to reflect on the Warsaw ghetto contested the prevailing propensity in Communist Poland to turn away from the most recent past, so too did increased sensitivity to the darkest moments of twentieth-century history pose a challenge to the oblivion of consumerist capitalism in the post-industrial era.Footnote 46

Few architectural projects express this impulse to reflect on absence and ruination more overtly than Daniel Libeskind's Jewish Museum. Shaped by Walter Benjamin's insistence on remembering the “wreckage” of the past lest it be forgotten by redemptive and ideological narratives of progress, Libeskind seeks to represent ruination in a newly constructed building.Footnote 47 His project takes up the task of mourning by promoting reflection on the “erasure and void of Jewish life in Berlin.”Footnote 48 A striking photo of his building taken during its construction brilliantly illustrates this point. Included by Libeskind in a lecture delivered at the University of Michigan, the photo captures a structure that looks like a ruin. The picture shows a hollowed-out shell of an empty building.

It is precisely such emptiness that Libeskind wanted to integrate into his building. As he explains, “Cutting through the form of the Jewish Museum is a void, a straight line whose impenetrability forms the central focus around which the exhibitions are organized. In order to cross from one space of the museum to the other, the visitors traverse sixty bridges that open into the void space—the embodiment of absence.”Footnote 49 Absence seems central to his design almost out of necessity. It is as if Libeskind could not respond to the task of building a Jewish museum in Berlin after the Holocaust in any other way. In a way similar to Lachert, Libeskind suggests that the particular history of the space on which his building stands determines what he can create artistically:

The void and the invisible are the structural features which I have gathered in this particular space of Berlin and exposed in architecture. The experience of the building is organized around a center which is not to be found in any explicit way because it is not visible. In terms of this museum, what is not visible is the richness of the former Jewish contribution to Berlin. It cannot be found in artifacts because it has been turned to ash. It has physically disappeared. This is part of the exhibit: a museum where no museological functions can actually take place.Footnote 50

Figure 6 Berlin's Jewish museum appearing as if it were a ruin. © Studio Daniel Libeskind. Photo by Manfred Beck.

Libeskind makes two claims here regarding the importance of history to his project. The first is that the Holocaust overshadows the previous history of Berlin Jewry since the traces of past Jewish contributions to Berlin have been destroyed. The second is that the museum cannot serve any museological function for reasons that Libeskind does not specify but which we might surmise as the following: first, that the rupture of the Holocaust has rendered the task of telling the history of German Jewry in the conventional form of the narrative difficult, and second, that the suffering and death of the victims cannot be used for any traditional pedagogical purpose because to do so would be to instrumentalize the Holocaust as an object of educational study. Libeskind's project calls into question the conventional historical and pedagogical aim of salvaging some kind of meaning from history.Footnote 51 As James Young writes, Libeskind's project represents “an aggressively antiredemptory design, built literally around an absence of meaning in history, an absence of the people who would have given meaning to their history.”Footnote 52

Young briefly touches on one of the most novel aspects of Libeskind's project. In centering his design on absence and ruination, Libeskind commits himself to a commemorative project that seeks nothing more than to mourn the suffering of the victims and the catastrophe of history.Footnote 53 It tries to perpetuate a non-salvific form of memory that reflects on the rupture of history rather than evading it as the conventional historical narrative does with its propensity to create a sense of continuity from the discontinuity and rupture of history.

The underlying issue here is history, or time. The historical narrative orders time into a cohesive and fixed account. This ordering of time rests on an unquestioned assumption about the “essence” of time. The historical narrative assumes an answer to the classic question: What is time? The answer given, since Aristotle, is that time represents the number of motion.Footnote 54 This concept of time suggests that there is some kind of “natural” or “raw” continuous sequence that can be calculated and organized into the historical narrative. By taking as self-evident the past as a continuous passing of something, the historical narrative presupposes that the past can be put back together in its original wholeness as if it were a broken piece of pottery. It is precisely this restorative or redemptive impulse that Libeskind's project brings into question. The past cannot, his project suggests, be salvaged and restored; history can only be represented as a ruin, as a collection of shards, as fragments that resist the narrative urge to bring them into a whole again.

Put differently, Libeskind commits himself to an artistic response to the Holocaust that comes close to embracing Adorno's claim that it would be callous to derive meaning from history. “After Auschwitz,” Adorno writes, “our feelings resist any claim of the positivity of existence as sanctimonious, as wronging the victims; they balk at squeezing any kind of sense, however bleached, out of the victims’ fate.”Footnote 55 For Adorno, suffering is central to history and the conventional attempt to give meaning to suffering through the historical narrative has collapsed after the Holocaust. One can only mourn past suffering. Mourning can remind us of the vulnerability that each of us faces as suffering beings and thereby strengthen a normative commitment to egalitarianism, but it cannot create a collective identity and memory around some kind of meaning imposed on the past for the needs of the present.

That Libeskind endeavors to realize Adorno's philosophical warning in an artistic project reflects great ambition and originality on his part, but his project faces two central challenges in doing so. The first concerns Libeskind's effort to represent absence in a building otherwise devoted to providing a cohesive historical narrative about German Jewry. If historical narratives offer continuity and order to the rupture of history, then a significant tension seems to exist between his project's content and its form,Footnote 56 for Libeskind's design explicitly challenges the conventional purpose of the historical narrative by insisting on absence and ruination.Footnote 57 “Although the program originally called for a chronological display,” Libeskind writes, “I have introduced the idea of the void as a physical interference with chronology.”Footnote 58 How does the void interfere with chronology? I think what Libeskind means is that the void challenges how the chronological, narrative account of history typically approaches history. Let me clarify this point by turning to an important distinction made in the German language between Historie and Geschichte: the word Historie, which derives from Latin, is the narrative told about a past event, whereas Geschichte, which comes from the German verb geschehen, is the past itself, the happening, the event. Geschichte is the dynamic unfolding of time that Historie aims to capture, order, and structure.

As a type of Historie, chronology orders Geschichte into a cohesive and holistic narrative. It turns away from absence by seeking to make the past present again, whereas Libeskind's project tries to turn toward absence by making it “the one element of continuity throughout the complex form of the building.”Footnote 59

If Libeskind's project seeks to approach Geschichte differently than Historie does, then a central tension between content and form courses through his project: while the exhibition makes German Jewish history present again through the chronological narrative, the building challenges precisely the narrative recuperation of Geschichte through its “embodiment of absence.”Footnote 60 Libeskind's building suggests that Geschichte cannot be recovered or made present again—it is a ruin that cannot be repaired. Now, one might say that this tension confirms the disruptive brilliance of Libeskind's art, and perhaps that is a fair point. But this point hinges on the very possibility of representing absence and ruination. Can absence be represented in a fully present building? Can a fully constructed building be a ruin of sorts?

These questions bring us to the second challenge of Libeskind's project, a challenge that Jacques Derrida raised, if briefly, in the “anxious question” that he posed to Libeskind about his void, “this determined void of yours, totally invested with history, meaningfulness, and experience.”Footnote 61 As Derrida explains, Libeskind's void is made visible, determinate, and full of meaning. Put simply, it turns out not to be a void at all:

This void which has to be made visible is not simply any void. It is a void that is historically determined or circumscribed; and it is not, for example, the indeterminate place in which everything takes place. It is a void that corresponds to an experience which somewhere else you have called the end of history—the Holocaust as the end of history.… The void you are determining here is the void as determined by an event—the Holocaust—which is also the end of history. Everything is organized from this end of history and from this void—this is what makes it meaningful.Footnote 62

Derrida claims that Libeskind's project turns out to affirm the metaphysical habituation to meaning and presence that it purports to challenge. Not only does Libeskind's project make absence present but it also inscribes the void within a stable and particular framework of historical meaning based on a determinate end. The Holocaust becomes the telos of Libeskind's project, the end that gives meaning to his void. Derrida suggests that Libeskind ends up turning away from absence insofar as he gives it a determinate form. His void conceals the emptiness it seeks to represent by attempting to represent it. By doing so, his project remains entrapped within the metaphysical tradition. Strive as one may to move beyond metaphysics, one can only ever fail to reach a new shore beyond it.Footnote 63

Derrida's critique opens up the central problem that any artist or writer faces, from the architect to the painter to the historian.Footnote 64 To wit, can one move beyond the limits set by the contexts of a tradition? In Libeskind's case the question becomes: Can there be a new kind of memory that transitions beyond the metaphysical orientation towards meaning, purpose, and redemption?Footnote 65 And if there can, then how might that memory be described? What is a memory absent meaning or sense? What is a memory of emptiness, absence, nothingness?

Hence, we might be left with appreciating Libeskind's project solely in terms of distinguishing it from what it aims not to do—in terms of what it tries to leave behind in its focus on absence. At its most suggestive, Libeskind's art strives to move beyond the conventional purpose of history as a form of salvation from the ruptures of history by creating a monument of absence and ruination.

MONUMENTS OF RUINATION

In this respect, Libeskind's project overlaps with Lachert's housing complex in Muranów. Although they are situated in different places and time periods, both come together in their analogous attempt to reflect on ruination and absence. To be sure, this is more directly expressed in Libeskind's project than it possibly could have been in Lachert's design for a Communist housing complex. But Lachert intended to memorialize the suffering of the ghetto. As mentioned earlier, he served on an expert panel that commented on Natan Rapaport's now famous ghetto memorial, which was unveiled in 1948. In his commentary on the monument, Lachert stressed that the “grim atmosphere of this great mausoleum, erected among a cemetery of ruins, soaked with the blood of the Jewish nation,” must remain as “new life comes into existence.”Footnote 66

The novelty of both of these memorial efforts warrants emphasis. If viewed from a broad historical perspective, monuments that intend to promote reflection on rupture and absence are atypical. The concept of the monument from its origins in the written record of European history has typically sought to nourish bonds of continuity, bonds that seek to overcome the pure evanescence of time and the finality of death.Footnote 67 The traditional monument immortalizes through stone.Footnote 68 The permanency it strives to establish may be individual or collective: one might build a monument to an individual whose life one wishes to commemorate, or one to an entire group of people whose actions and values one wishes to perpetuate across generations.

In contrast, the Libeskind and Lachert projects, like a number of others in the postwar period, intend to nourish a different kind of remembrance that reflects on discontinuity, absence, and death.Footnote 69 If both projects obviously promote continuous remembrance, it is a remembrance that calls attention to absence and ruination—it is a remembrance that undermines the traditional purpose of the monument. Having said that, both memorial efforts were limited by the conventional demands of memorialization under which the two men worked. In Lachert's case, the demands came from the Communist Party, which sought to ground its authority in a national narrative of rebirth. His reflection on the ghetto space challenged this salvation narrative and the party ultimately rejected it. It then appropriated Muranów as a space to showcase its effort to bring Warsaw from the darkness of the past to the light of material prosperity—from reflection to oblivion. In the case of Libeskind, his intentions were hindered in two ways: (1) by the form of his memorial project, as Derrida noted in his critique of Libeskind's effort to represent ruination and absence in a newly constructed building; and (2) by the historical, pedagogical content housed in his building—that is, the museum's narration of German-Jewish history intrinsically contradicted his aspiration to perpetuate a memory oriented towards absence, ruination, and rupture. Despite the limitations each of these projects faced, they both challenge not only the forgetting of suffering in the postwar period but also the general propensity to turn away from the fragility and vulnerability of the human condition.