‘Oh Lor’, I know it you call my name. Nobody don't callee me my name from cross de water but you. You always callee me Kossula, jus'lak I in de Affica soil!’

So you unnerstand me, we give our chillun two names. One name because we not furgit our home; another name for de Americky soil so it woun't be too crooked to call.

———Cudjo Lewis, in Barracoon (Zora Neale Hurston Reference Hurston, Plant and Walker2018 [1931]: 17, 73)INTRODUCTION

The act of naming, and of recognizing ourselves by the names we are given, often seems such a universal aspect of human experience as to be second nature. Indeed, in most cultures and social circumstances, personal names function not only as identifiers, but as a locus for identity. Perhaps, however, the social power of naming and its capacity to shape the life course of the person named becomes most evident when it is used with the opposite intent: to injure rather than individuate. Such practices have long been integral to processes of colonization and enslavement, to the extent that societies built around empire and slavery develop recognizable onomastic systems and repertoires intended to mark out citizens from subjects and enslaved (Scott, Tehranian, and Mathias Reference Scott, Tehranian and Mathias2002; Benson Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006). As Saidiya Hartman has observed, “The classic figure of the slave is that of a stranger. Torn from kin and community, exiled from one's country, dishonored and violated, the slave defines the position of the outsider” (Reference Hartman2008: 5).

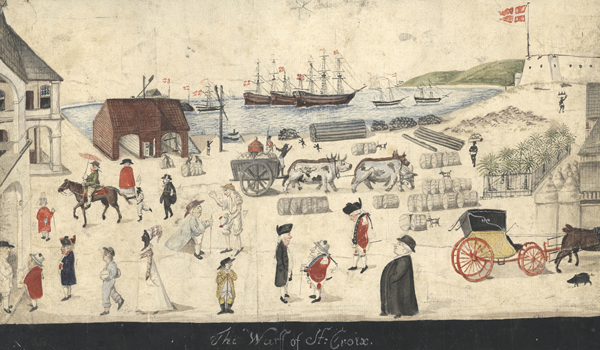

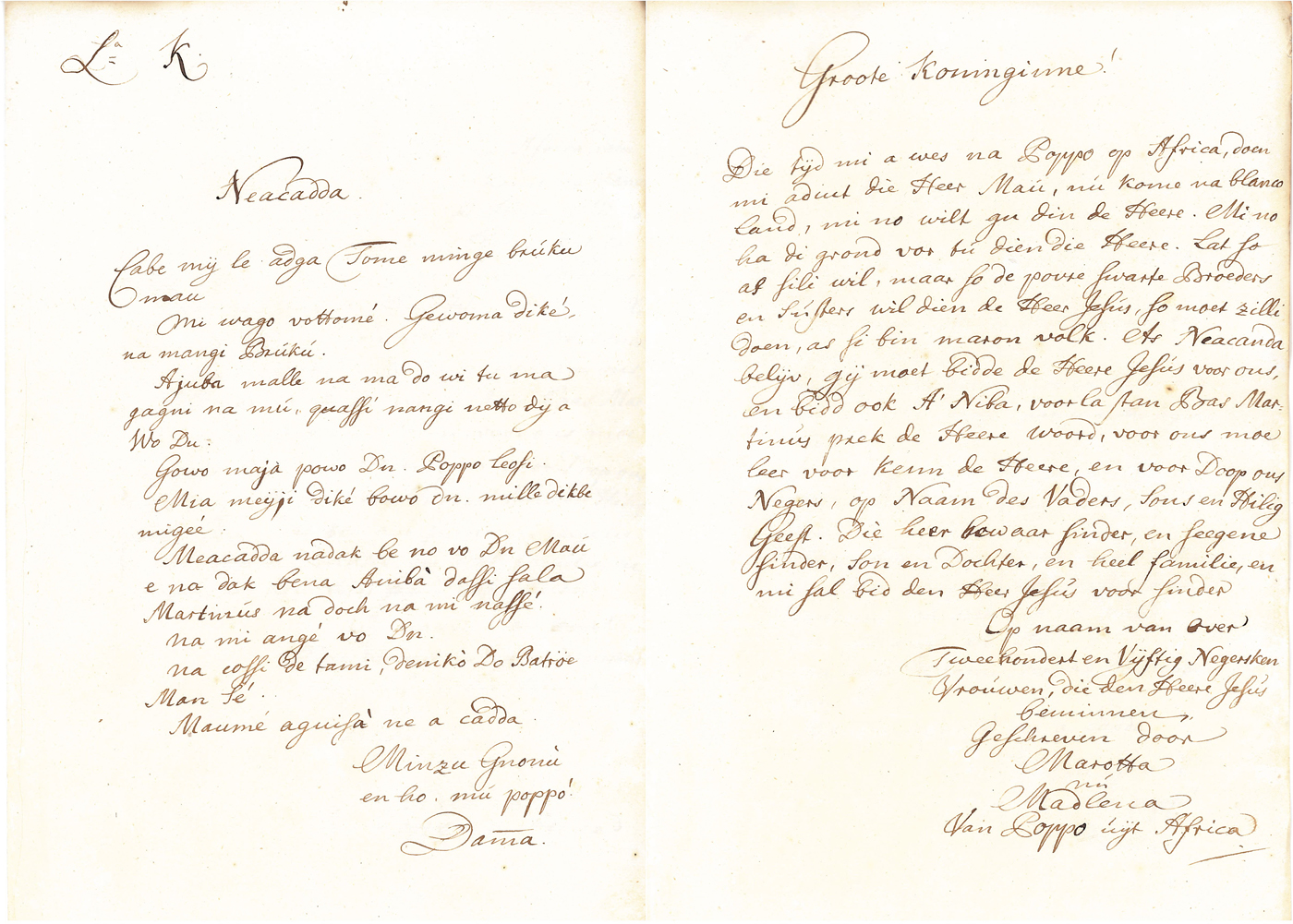

The focus of this article, the Danish plantations in the West Indies during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, were multicultural colonies inhabited largely by enslaved Africans and slave owners and administrators from Britain, Ireland, and the Netherlands, with small numbers of Danes, French, and North Americans. In this paper we aim to add to historical and anthropological discussions on names and naming practices in the context of Caribbean slavery, through our analysis of historical documents and datasets from the island of St. Croix. Louise Sebro has remarked that close examinations of population databases for the island “will undoubtedly throw light on traditions of name giving” (Reference Sebro2010: 198). Our contribution here consists of an analysis of 197 names from a plantation register taken for tax purposes in 1785, as well as the names contained in 1,426 baptismal records pertaining to two churches in St. Croix. One is a Lutheran church (1780–1794) in the capital city of Christiansted (image 1), whose congregation was made up of white, free colored, and enslaved individuals; another is Friedensthal Moravian Church (1744–1832), located on the outskirts of Christiansted, whose congregation consisted primarily of enslaved individuals from nearby sugar plantations as well as free people of color. Our analysis is further illuminated by details from the lives of three former slaves from the Danish West Indies.

Image 1. The Waterfront at Christiansted, St. Croix. H. G. Beenfeldt (1767–1829). Courtesy of M/S Museet for Söfart, Helsingör, Denmark.

There exists already a considerable body of studies on the names given to enslaved individuals and documented in colonial records. Some scholars have focused on the onomastics and etymologies of the names used to designate the enslaved in historical records, searching for names that functioned as markers of origin, kinship, or ethnicity (Thornton Reference Thornton1993; Álvarez López Reference Álvarez López2015). Others have analyzed slave names as vectors for social relationships, contemplating, for instance, the dynamics of power between enslaved individuals and the authorities charged with (re)naming them (Hébrard Reference Hébrard2003; Cottias Reference Cottias2003); how naming patterns can indicate processes of acculturation, creolization, and racialization—or, conversely, efforts at cultural resistance and self-determination (Inscoe Reference Inscoe1983; Zeuske Reference Zeuske2002); and what the switching or maintenance of names in transitions from slavery to emancipation reveals about the stakes of attempting to name oneself (Durand and Logossah Reference Durand and Logossah2002; Benson Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006).

Colonial documents were generally written to itemize the properties of colonists, tracking sales, inheritances, and taxes, and as a result they typically excluded other personal names used privately and familiarly within communities of Africans and their descendants, names that were perhaps unknown to their legal owners. Here, ethnographic data can provide further context and supporting evidence: for instance, the idea that enslaved Africans may have used multiple names, simultaneously and strategically, for themselves and others, chimes with practices in various West African cultural contexts in which names change to mark social transitions or are acquired cumulatively over the course of a person's lifetime (Odotei Reference Odotei1989; Adjah Reference Adjah2011).

Having access only to the records of slave holders also means that glimpses into the microworlds of the persons involved are rare. Providing dense anthropological descriptions of the social and political environment in which acts of naming take place can help avoid deterministic assumptions linked to the etymologies of names. Recognizing that subjectivity, identity, and naming are inevitably informed by local contexts, our discussion of St. Croix baptismal records addresses how far the adoption of European and Christian names can be read as efforts toward resistance and self-determination on the part of the enslaved, and how these appropriations can be squared against colonial authorities’ attempts to preserve racial distinctions in spite (or in light) of the rapid creolization of the island's African-descendant populations.

While the church records we use offer important insights into patterns of naming during and after the Middle Passage, they are not “thick descriptions” in the Geertzian sense (Geertz Reference Geertz1973), interrogating stratified layers of language and meaning. Like other scholars, our inquiries are shaped by the desire to understand who named slaves and in what circumstances. To what extent can names embody opposing power dynamics, acting simultaneously as a signifier of both domination and resistance? And, to paraphrase Susan Benson (Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006: 198), if names always bear the burden of their histories, can anyone ever name themselves?

In this respect, microhistories in the fashion of Natalie Zemon Davis (Reference Zemon Davis2011), which permit scholars to follow individuals over the course of their lives, and particularly through their transitions from enslavement to freedom, have proven useful in terms of understanding how the enslaved chose to represent themselves in different settings and contexts (Thorp Reference Thorp1988; Sensbach Reference Sensbach2005; Sebro Reference Sebro2010; Reference Sebro and Weiss2016). Our account is therefore illuminated by details of three enslaved people living in the Danish West Indies who later became free: Mercy (1755–1850; also named Mary Wade and Cathrine Lawrence), an “African woman” on St. Croix; Dama (d. 1747; also named Marotta and Madlena), born in Popo, West Africa and forcibly transported as a young woman to the island of St. Thomas; and Hans Jonathan (1784–1827), a “mulatto” creole born in slavery in St. Croix, who later escaped to Iceland where he settled down and built a family.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: CAPTURE, THE MIDDLE PASSAGE, AND ENSLAVEMENT

From the sixteenth century, European colonists bought captive men, women, and children from the coasts of West and West Central Africa and transported them to colonies in the Caribbean and the Americas, where they were sold as slaves and forced to work on plantations or as domestics for European settlers. Although the laws and customs surrounding the institution of slavery differed from colony to colony, one generalized feature was that a slave's status was lifelong and inheritable.Footnote 1 This meant that, by law, enslaved Africans belonged to their owners for life, as did their descendants, unless they managed to secure their freedom.

Beginning with their capture in the interior of Africa, often at the hands of slave-raiders or merchants from warring kingdoms and nations (Hernæs Reference Hernæs1998: 131–39; Ipsen Reference Ipsen2015: 12), the captives would endure various processes designed to dehumanize them and divest them of their individuality. They were bound or chained and forced to trek long distances by foot to the coasts. Upon arrival at the African port towns they were sold to European slave-traders in exchange for cowries, armaments, and other commodities. To record the exchange, the Europeans drew up lists of their purchases, detailing certain characteristics that helped determine the captives’ market value (e.g., age, sex, wounds, signs of illness). The lists sometimes included transcriptions of the captives’ names, recorded by trading company merchants so as to identify and track their “goods.” As Jean Hébrard has noted, “These were the names from before slavery that the following stages in the process would definitively efface” (Reference Hébrard2003: 40).

After being registered, the captives were branded on the arm, chest, or thigh with the initials of the company that had bought them. Once transferred to the slave ships, they were chained up and made to lie below deck in cramped and filthy conditions, sometimes staying there for months until the ship had assembled a full cargo. Before departure from the African ports the ships were subjected to customs checks and cargo lists were drawn up to facilitate that process. At this point, the record-keepers did not waste time distinguishing individuals by name and simply enumerated them in the ship's manifest as “heads” or “pieces” of merchandise.

In the sixteenth century, the so-called Middle Passage (the voyage from the African coasts to ports in the Americas and the Caribbean) might last up to three months; by the eighteenth century the journey was typically down to one month. Nonetheless, there was considerable “wastage”: it has been estimated that 12–13 percent of the 12.5 million Africans embarked onto slave ships throughout the period of the trade perished through disease or malnutrition, or were killed at the hands of their captors during efforts at resistance (Eltis Reference Eltis2007). Those who survived the passage had to pass customs and sanitary controls upon arrival at the Caribbean or American ports, before being transferred to slave markets where they were prepared for sale. Planters, middlemen, and other speculators would feel the “goods,” inspect them for any wounds, and estimate their potential future value. It was upon being purchased that most captives first received a slave name in the American colonies.

From the perspective of colonial administrators in the New World colonies, incoming captives arrived nameless, and it was the duty of their first owner to assign them the formal name by which they would be identified in official records. The eighteenth-century French chronicler Médéric Louis Élie Moreau de Saint-Méry gave the following description of the process involved in recording a slave name, witnessed on his native isle of Martinique: “As soon as the Negroes are bought from a slave-trader, they must be taken to the office of the depot, where they are stamped on the outside of one shoulder, with a letter S; the buyer's name is recorded as well as the name he judges fit to give to the Negro” (Moreau de Saint-Méry Reference Moreau de Saint-Méry1797: 685).

From the perspective of the slave-owner, naming slaves served a primarily practical function: it was the essential first step in the commodification of human beings and in the “writing of property”—on the skin of the body and on paper—which meant that the incoming captives could be bought, sold, mortgaged, adjudicated, and so forth. The people branded with these names were integrated into a new, essentially capitalistic, socioeconomic context in which they would live—and had to learn to live—over the rest of their lives. Renaming constituted an act of erasure, underscoring the rupture between the people they had been and the non-people they were to become.

PEJORATIVE NAMES

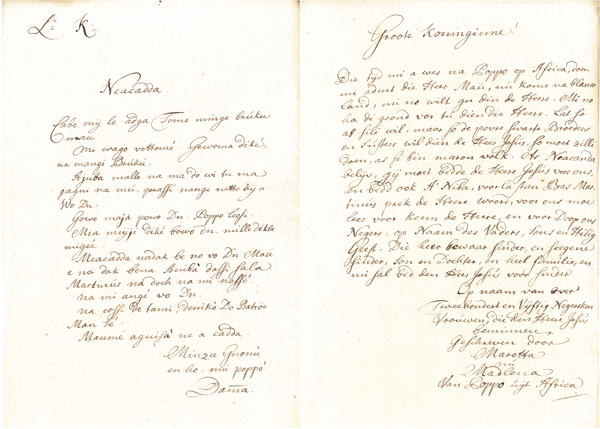

Some examples of slave-naming practices in the Caribbean colonies can be found in a 1785 head tax list for one of the plantations owned by the Schimmelmann family on the island of St. Croix (image 2).Footnote 2 One notable point is the great diversity of slave names found on the Schimmelmann list (131 unique names out of a total of 197). This reflects a widespread tactic used by plantation owners to assign their slaves distinctive labels, singling them out to facilitate the division of labor, the meting out of punishments, and the general handling of their stock (Cody Reference Cody1987: 571–72). The indifference with which the slave names were allocated is particularly evident in instances where two individuals shared a same name, and the suffix “B” was tacked on to differentiate between them (John, John B; Prince, Prins B).Footnote 3

Image 2. Head tax list from Constitution Hill, St. Croix, 1785. Den vestindiske regering. Gruppeordnede sager. Matrikeloplysningskemaer (1772–1821) 3,81,493 for plantagerne 1785. Courtesy of the National Archives of Denmark, Copenhagen.

Many of the names on Schimmelmann's list correspond to Benson's (Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006) characterization of “injurious” names, intended to mark slaves out by drawing upon naming forms not used by the dominant class. For instance, some are not personal names, but refer instead to places (London, Madrid, Dublin), animals (Zebra, Fox), or qualities (Amor). Another popular category includes names of classical figures (Cicero, Ancilla, Cupido). Such names functioned as cruel jokes: for instance, Scipio, a common male slave name, referred to the Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, whose agnomen, Africanus, meant “the African,” in praise of his triumphs in battle in North Africa. Names of Greek and Roman heroes, philosophers, and orators were popular choices for male slaves, underlining their degradation and emasculation via their juxtaposition with these great men. Meanwhile, as Saidiya Hartman has noted, names like “Venus” for female slaves reflected and licensed the lasciviousness of European slave-owners toward African women, making such behaviors “sound agreeable” (Reference Hartman2008: 143).

In forcing slaves to answer to their imposed names, slave-owners engaged them in what Benson has called “a tyrannous act of interpellation” (Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006: 184), impelling them repeatedly to acknowledge their own subjection and powerlessness. They resisted the possibility that a slave might make a life-changing decision by choosing a new name, for this symbolically granted the enslaved person a degree of autonomy, setting them free from the owner's power domain (Sebro Reference Sebro2010: 201). Yet it should be noted that these slave names were not the only ones used in the plantation.

RESISTANCE AND ADAPTATION

A significant amount of evidence indicates that enslaved Africans continued to use their own names after arriving in the American colonies. Trevor Burnard, for instance, cites accounts of slave-owners or European travelers who observed enslaved Africans using different names from the ones assigned to them by their masters, suggesting an ongoing complicity and covert resistance to the imposition of slave names among enslaved communities (Reference Burnard2001: 330). Such examples contradict the idea that these individuals left all aspects of their former personhood behind as they boarded the slave ships. As Grey Gundaker has written, a dearth of possessions need not be equated with a reduction in cultural resources (Reference Gundaker2000: 126); enslaved Africans in the New World were clearly not the tabulae rasae their masters wished them to be.

In other instances, it is less clear what or whose intentions underlie the slave names on Schimmelmann's list. Examples of months being used as personal names (“July,” “Februar”) could have referred to the time of year when a newly disembarked African captive was acquired, or the birth-month of a slave born in the colony (Oldendorp Reference Oldendorp and Beck2002 [1777]: 513). Conversely, Cheryll Ann Cody has suggested such practices may indicate the persistence of West African customs of naming children for the day they were born (Reference Cody1987: 573). Some African names, including Akan day-names (Quacoe, Quamina, Codjoe), can also be identified within Schimmelmann's list, along with others of West African origin (Tam, Jamba, Talla). However, such names do not necessarily denote African cultural “survivals” or self-naming practices in the plantation. David DeCamp (Reference DeCamp1967) has argued that, in Jamaica, Akan day-names were assigned to enslaved Africans by slave-owners, who were not necessarily aware of their original cultural significance. In Jamaican slave society the names took on new, pejorative meanings—no longer functioning as part of a dynamic system that created links among peers and across generations, but instead serving as racial stereotypes to describe certain “types” of “Negroes.”

These examples support Herbert Gutman's warning against interpreting the persistence of African names in the historical records as a sign of resistance and cultural resilience, and the use of European names as the result of processes of domination and subjugation (Reference Gutman1976: 244). Clearly, enslaved Africans did not simply undergo a passive process of acculturation from their entry into the colonies, resulting in the assimilation of dominant European norms. Instead, as Mary Louise Pratt (Reference Pratt2008: 7) has observed, the colonies were “contact zones” in which Africans, Europeans, and their descendants were all subject to the effects of transculturation (Ortiz Reference Ortiz1947: lviii–lix). Thus, rather than regarding enslaved Africans as victims of the eradication of oppressed cultural patterns through the progressive adoption of hegemonic forms, we can see them as social actors engaging in strategies of creolization.

CREOLIZATION

According to Gundaker, the concept of creolization “involves both innovation and the use of historical resources and precedents” (Reference Gundaker2000: 130). While the term implies a process of mixing, she notes that its result “often consists of pointed contrasts rather than [the] meltdown of elements into new (chemical-like) solutions” (ibid.: 127).Footnote 4 This image of incongruence and internal variation suitably describes the differing degrees of cultural appropriation, strategies of resistance, and cultural resources that can be observed within the communities of slaves and free people of color in the New World. Far from being internally homogeneous, these groups encompassed significant ethnic diversity among African-born slaves, as well as social and racial stratification arising from structures and hierarchies established within the colonies.

Take, for instance, the differing experiences of African-born slaves and their children born in the colonies, known as “creoles.” According to Cudjo Lewis, quoted in this article's epigraph, who was among the last group of captive Africans shipped illegally to the United States in 1860, Africans often gave their children two names: one from their “home” in West Africa, and another that their American children could better pronounce. These individuals grew up speaking European languages and Creoles, and the naming traditions of their parents and grandparents would have been increasingly unintelligible as the generational distance from their African origins grew. If they received secret African names, as Lewis suggests, these may have seemed to them unpronounceable and dissonant. Some would have European as well as African ancestry, due to slave-owners’ widespread sexual abuse and coercion of female slaves, and strategies by the latter to improve the conditions of their children.

Moreover, creole slaves were often afforded more opportunities for social contact with slave-owners and their families, who typically regarded them as more “civilized” than their African-born parents, and therefore more apt for skilled and domestic work. It was generally “mixed-race” or “mulatto” creoles who were selected to work in the big houses (Gomez Reference Gomez1998: 228–30). Some likely identified and felt more familiar with the language and culture of the family they served than with those of their kin out in the fields and the slave quarters (Sensbach Reference Sensbach2005: 36). This sense of increasing cultural proximation with the white slave-owning families is perceptible in the names found in Schimmelmann's list, which is divided into “House Negroes” and “Negroes belonging to the Estate.” Among the thirty-four “House Negroes,” only two bear pejorative names (Scipio, Phirrus) and the rest have common European names.

Although white colonists may have welcomed signs of creolization among their house slaves, they also took care to impose additional onomastic markers that reinforced the social gap between slaves and free (white) citizens. One common practice in Crucian society and other parts of the Americas was the proscription of patronymic surnames for slaves. As Scott, Tehranian, and Mathias have described (Reference Scott, Tehranian and Mathias2002), the imposition of systems of permanent, heritable patronyms in European societies has been a relatively recent historical innovation, notably linked to the documentation of private property rights and inheritance procedures. Since chattel slaves were, by definition, property, they were legally denied patronymic surnames in most colonies.Footnote 5

In the eyes of many colonists, the greatest threat to their social and economic hegemony was posed by emerging classes of free people of color. In 1775, Governor General Clausen of the Danish West Indies, prompted by demands from the free white community, denounced ex-slaves in the colony who had taken the names of their former owners and conferred them upon their own children, an act he branded as disrespectful and a potential cause of future confusion for white families of the same name. This may have been a veiled caution against instances in which the mixed-race descendants of white owners might claim rights to their father's inheritance, in competition with his white offspring (e.g., Reis Reference Reis2006: 101–2). Free blacks and mulattoes were henceforth banned from using their ex-masters’ patronymics in this way, unless they followed the formula “N.N. manumitted by N.N.” (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 145). Overall, these measures were linked to concerns about shoring up the frontiers of whiteness and asserting racial dominance in the face of a growing free population, which was steadily filling and narrowing the social gap between the ruling colonial classes and the enslaved.

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

So far, we have chronicled some of the main junctures at which Africans and their descendants were formally named and renamed during their trajectories between enslavement and freedom in the European colonies of the Americas. Our account has mainly dealt with secular naming acts and contexts: for instance, marking the entry of African captives into the New World colonies, denoting the sale of chattel from one owner to another, and signifying a legal change in status from slave to free person. In the following two sections we will explore the opportunities that Christian churches offered for naming and renaming through baptism in the Danish West Indies, and the extent to which these rites afforded enslaved individuals and free people of color potential for self-definition and social transformation.

The Danish West Indies (St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix) came under the possession of the Danish Crown between the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, with St. Thomas conquered from the Dutch in 1666, St. John settled in 1718 by the Danish West Indian and Guinea Company, and St. Croix purchased from the French in 1733. By the eighteenth century, the official state church of Denmark was Lutheran, a Protestant denomination. However, not until 1755, when the Crown simultaneously inaugurated a Lutheran mission to the Virgin Islands and issued its “Reglement for Slaverne”—which mandated, among other things, that slave children be baptized at birth—did the Lutherans begin to take a slightly more active role among the enslaved and free colored populations (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 47; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2001). Initially mission work, carried out within the framework of the official church, which catered primarily to Danish-born officials and residents, proceeded slowly, with only a few conversions. Even after a separate mission congregation was formally established in 1788, membership remained small and largely confined to the urban free colored and enslaved populations.

In fact, throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was representatives of the Moravian Church from eastern Germany who had the greatest contact with the slave populations in the Danish Caribbean (Oldendorp Reference Oldendorp and Beck2002). A first group of missionaries arrived in St. Thomas in 1732, and over the following decades the Moravian Brethren played an increasingly important role in the lives of the enslaved communities throughout the three islands (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 46). As the Moravians saw it, the “Negroes” of these colonies were afflicted by God's curse upon Ham, and their enslavement was justified by his divine retribution against their progenitor. Nonetheless, the Brethren felt compelled to preach among enslaved Africans, administering baptismal rights to those “whom God had chosen,” and accepting a select few as members and missionaries in the church (Thorp Reference Thorp1988: 440–41). According to the estimates of one contemporary observer, Moravian missionaries had baptized almost 4,600 slaves in the Danish Virgin Islands between 1732 and 1767, while over a thousand of these had taken up full membership in the Moravian Church by 1767 (Thorp Reference Thorp1998: 2).

At the same time, the Moravian leaders made clear that the spiritual liberty that Christian conversion offered to enslaved Africans was not tantamount to legal freedom. Likewise, the paragraph of Frederik V's 1755 Reglement relating to Lutheran slave baptisms stated that “slaves were not to become free by virtue of becoming Christian, but to remain slaves no less obliged to owe their masters and owners obedience, diligence, fidelity and other duties” (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 47). Indeed, Neville Hall has argued that the Christian message propagated by the Moravians was intended to quell ideas of legal emancipation and instead promoted “to a place of pre-eminence the virtues of obedience, patience, resignation and humility which singly or in combination were powerful instruments of social control” (ibid.: 46).

Nonetheless, baptism did confer concrete privileges upon Africans and their descendants in the New World, like the right to bear witness under oath at trial (Highfield Reference Highfield2004: 28). During historic legal proceedings in Copenhagen in 1801–1802, involving the rights of plantation owner Henrietta Schimmelmann over Hans Jonathan, a “mulatto” from St. Croix, the issues of baptism and confirmation were repeatedly raised as witnesses were called to the stand (Palsson Reference Palsson2016: 101). The Moravian Church, moreover, taught its members to read and write, activities otherwise inaccessible to slaves, and occasionally sent its most promising proteges abroad to spend time in Europe and North America among other missionaries (Highfield Reference Highfield2009: 124; Sensbach Reference Sensbach2005). Given their strong doctrinal interests in suppressing informal alternatives to Christian marriage, the Moravians may have also offered some protection to family integrity among the enslaved, who were otherwise vulnerable to separation (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 84).

Yet, baptism into the Lutheran or Moravian church must have seemed to many enslaved Africans to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the 1755 Reglement made baptism obligatory for creole infants, meaning that African parents could no longer legally resist the formal Christianization of their children. This fact may partly explain the extremely high levels of church membership among slaves in St. Croix, which reached around 99 percent by 1835. Following the abolition of the Danish slave trade in 1803, there was no longer a regular influx of Africans to the colony and the slave population was thereafter renewed by newborn creoles, who were baptized by law.

On the other hand, newborns were not the only enslaved individuals to undergo baptism in St. Croix. From the outset, the Moravian and Lutheran churches, as well as the Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Dutch Reform churches, baptized enslaved and free colored individuals of all ages. The presence of large numbers of enslaved and free adults among these congregations meant that church membership was not only a status that was forced upon slave children, but something that many African and creole adults chose for themselves and their children.

ST. CROIX CHURCH RECORDS

We now take a closer look at the names recorded in the St. Croix baptismal registers for enslaved individuals and free people of color. Our data correspond to three sets of church registers from Christiansted: one from the Christiansted Lutheran Church, later named Lord God of Sabaoth, and two from the Moravian Church at Friedensthal (see table 1).

Table 1: Baptismal records analyzed from three sets of church registers in St. Croix.

The files record different types of information, and therefore offer different scopes for discerning naming patterns and practices. The Lutheran records relate to 251 baptisms of slaves and free people of color between the years of 1780 and 1794. In the records for baptized infants, the child's name is listed alongside those of its parents (or at least that of its mother), meaning that some inferences can be made about patronymic and matronymic naming practices within families, although only within two generations. Details are also provided about the racial category of the baptized (Negro, Castice, Sambo, Mustice, Mulatto, White), as well as their legal status (free or slave). In the cases of adults who were baptized, forty out of forty-nine individuals changed their name, permitting us to study patterns among the new names that these slaves and free individuals received during baptism.

The baptismal registers that we have selected from the Moravian Church at Friedensthal are split into two. The first set pertains to the baptisms of 821 slaves between 1744 and 1832 from La Grande Princesse plantation, which was owned by Ernst Schimmelmann, minister of finance in Denmark 1784–1813 and one of the leading lights of the powerful Schimmelmann family. La Grande Princesse was a focal point of Moravian proselytization and recruitment among the African descendant populations in St. Croix during the eighteenth century (Hall Reference Hall and Higman1992: 192–93). The registers do not reference racial categories of those baptized, but they do record their birthplaces (Creole St. Croix; Creole St. Thomas; Africa, Mandingo; Africa, Amina, and so on), showing that just over a third (131) of the baptized adults were African-born. With regards to adult converts, the records include extensive data of name changes through baptism (295 instances in total, accounting for around 80 percent of all adult baptisms), which we examine presently. The records also include the death date of many of the baptized, making it possible to search for potential necronymic practices.

The second set corresponds to 354 baptisms of free people of color and their children at the Friedensthal Moravian Church between 1752 and 1832. In the records for baptized children, as with the Lutheran set, the latter's names are listed alongside one or both of their parents, allowing a limited examination of possible patronymic and matronymic naming practices. While the records do not mention racial categories, they do register the status of the parents (enslaved, free colored, or free white), from which the status of the child can be inferred since children took the legal status of their mothers. Among these, 162 are children of a free colored mother and enslaved father; eighty-one of a free colored father and an enslaved mother; forty-eight of an enslaved mother and white father; and twenty-four of a free colored mother and white father. This dataset also contains thirty-nine registers for baptisms of free colored adults, of whom thirty-five underwent name changes.

Christian Names

One immediately obvious characteristic is the universal attribution of Christian names (i.e., etymologically European names relating to biblical characters or saints) to both infants and adults undergoing baptism in both churches. While this observation may seem tautological, it has several possible implications in terms of assessing who chose the baptismal names, what the purpose of renaming was in this context, and what guidelines or cultural mores influenced the choice of some names to the exclusion of others.

In all cases, adult converts with African names (of which most examples were found in the La Grande Princesse files, sixty-five overall) received a new name through baptism. Our data also yielded no clear examples of infants receiving etymologically African names through baptism. We cannot be sure whether this was due to an overt prohibition on the part of the clergy, although Daniel B. Thorp's (Reference Thorp1998) analysis of Moravian attitudes to non-white converts in the New World indicates that the missionaries felt it was their duty to eradicate signs of converts’ prior “heathen” ways, and African names could have been viewed as one such marker.

However, quite often, adults bearing etymologically European names also underwent name changes through baptism. Some of these can be classified as “slave names,” according to the characteristics outlined above, and they were always substituted for Christian names (we found forty-three such cases among the two Moravian datasets, and eight among the Lutheran set). Svend Holsoe (Reference Holsoe, Highfield and Tyson2009) has analyzed one such case in detail, of an African woman brought from the Gold Coast to St. Croix in 1770. Upon her arrival, she was purchased by a Dr. Johan August Naeser, who gave her the name “Present.” Over the following decade she bore at least four children, some of them likely fathered by Naeser. In the 1780s, however, Present was sold to another owner, Maria Kierulff. Around the same time, she was baptized in the Friedensthal Moravian Church, where she took the name “Dorothea.” After more than a decade of living under a slave name that condoned her owner's licentiousness, Holsoe (Reference Holsoe, Highfield and Tyson2009) interprets this name transition as a major personal decision, and an indication of self-determination.

A further category of name-changers includes seventy-five individuals (sixty-nine from the Moravian sets, and six from the Lutheran set, including both Africans and creoles) bearing diminutive European civil names (Betty, Nanni, Dick, Jacky). These can also be considered a type of slave name, in that they denote familiarity and are often reminiscent of the “pet” names given to children or animals, indicating the psychological capacities owners attributed to their slaves. In both cases, we can see receiving a Christian name through baptism as having marked the slave's transition from chattel—or, at most, a primitive and childlike being—to a person, “touched” by God (Thorp Reference Thorp1988: 441) and worthy of a “real” name. For enslaved individuals, it may have represented an opportunity to rid themselves of names that marked them out as outsiders and receive others that signified their integration into a community.

The largest proportion of name changes, however, are found among individuals who already bore non-diminutive Christian or European names prior to baptism. These people either changed an existing Christian name for a different one (e.g., Paulus to Petrus; Maria to Rebecca), or augmented their name, usually by affixing an additional name to it (e.g., Anna to Anna Johanna; Marcus to Johann Marcus). There were 172 such cases overall, accounting for 43 percent at the Lutheran Church in Christiansted, 26 percent at Friedensthal Moravian Church, and 38 percent at La Grande Princesse.

In all cases, only a small percentage of adults were baptized without undergoing some kind of name change: 18 percent at the Lutheran Church, 10 percent at Friedensthal Moravian Church, and 16 percent at La Grande Princesse. The birthplace information included in this last dataset allows us to see that over four-fifths of these individuals were creoles. Without exception, these adults already had either single (Charlotta, Barnabas) or composite (Georg Heinrich, Anna Maria Kirstina) Christian names before undergoing baptism.

What do these trends denote? Firstly, with respect to the two essentially urban congregations, that a large proportion of the enslaved and free converts already had Christian names, and either kept these or augmented them through baptism, seems to indicate that a particular social appeal or advantage lay in formally giving such names to one's children, or taking them for oneself. In the cases of enslaved individuals who kept their names, nearly all of the Christian names corresponded to names found on inventories and head tax lists (such as the 1785 list for Constitution Hill discussed earlier), implying that many of these names were likely given to them by their owners. That they retained all or part of these names at baptism may indicate a pragmatic desire by the Moravians to link them to particular properties or owners for management purposes. On the other hand, it is possible that some of the names came from their own kin, which would suggest an impetus to appropriate the names used among white colonial society for their own children out of religious conviction and/or a desire to fit into the Christian communities and traditions that were increasingly open to them.

At the same time, the vast majority of the rural La Grande Princesse slaves underwent name changes through baptism, even when they already had a Christian name, which may indicate the symbolic and spiritual importance that was linked to the ritual. This was certainly a belief of the Brethren, who regarded baptism as a redemptive moment and an opportunity for followers to pledge their lives to serving Christ in the Moravian fashion. Some first-hand accounts written by black Moravian converts suggest that this was also a pivotal moment for the baptized (Sensbach Reference Sensbach2005: 38–39; Thorp Reference Thorp1988: 443). In his examination of Andrew the Moor's account of his conversion to a Moravian congregation in Pennsylvania in 1746, Thorp notes that Moravian leaders liked to choose baptismal names that would link new converts to biblical characters, or even to contemporaries who could act as moral guides and inspirational figures for their new Christian life. For instance, Andrew himself was named after another African bondsman (the original Andrew the Moor) who, until his death two years earlier, was well known among the Moravians for having faithfully served the organization's leader, Nicolaus Ludwig, Count von Zinzendorf (Reference Thorp1988: 443).

Indeed, a preference for names that reference biblical characters is particularly noticeable among the Moravian baptism records from La Grande Princesse, which drew upon a wider and more obscure pool of names than either of the two urban congregations. Some of the more unusual names, which nevertheless occur several times among the baptismal registers, were likely chosen to invoke parallels with Bible stories and teachings. Examples are Bilha (six baptisms), in reference to Rachel's maid who bore Jacob's children on behalf of her mistress; Manassee (six baptisms), in relation to Manasseh of Judah, who was known for his worship of foreign gods; and Priscilla (five baptisms) and Aquila (seven baptisms), a married couple mentioned in the New Testament as early Christian missionaries.

The act of renaming also echoes several instances in the Bible where characters receive a new name to mark a moment of spiritual liberation or personal change, for instance Jacob receiving the name Israel, or Saul being renamed Paul at God's bidding (Chanson Reference Chanson2008: 49). Around 80 percent of the 295 adult slaves from the plantation who underwent name changes received a completely new name (i.e., they did not simply augment their existing name); however, 29 percent of this number received names that retained a phonetic or alliterative link to their previous name (Wanu to Wilhelm; Pyrrho to Petrus; Anna to Hanna; Caritas to Cicilia). Could this trend denote the name-receivers’ desire to resist a complete separation from their pre-baptismal identities? Or was it merely a mnemonic device designed to help religious leaders and converts recall each other's new names? In any case, such radical name changes gradually became less frequent over time at La Grande Princesse, so that in later years—particularly after the turn of the nineteenth century—Moravian converts tended to either keep an existing Christian name or to augment it through baptism. As with the urban black communities, this pattern points to a progressive preference for choosing Christian names for newborn children among this rural enslaved population, in tandem with the dwindling of its African-born members following the abolition of the slave trade in 1803.

Children's Names

In contrast to the cases of most adults, entries relating to children baptized at the Lutheran and Moravian churches register only one name: the Christian name given to them at baptism.Footnote 6 Most were newborns and the names they received through baptism were likely to be the official designations by which they would henceforth be documented and known in colonial society.

Who chose these names? Among the Moravian records from La Grande Princesse, there are few clues, but the limited evidence suggests it was the clergy in most instances that involve the enslaved. There are no noticeable differences among the type of name given to children and those given to adults, and indeed, the same biblical-style names occur among both. Moreover, since children were not inscribed alongside their parents at baptism, it is impossible to track genealogical patterns in the attribution of names for this particular dataset. However, we were able to identify some possible instances of necronymic naming, where a newborn or adult convert was attributed the same baptismal name as an adult who had died during the previous year (see also Cody Reference Cody1987: 595). Although some of these instances may be coincidental, others seem convincing. For instance, a creole slave named Wilhelmina (originally Martha) was baptized in 1762, and died forty-three years later, in 1805. In February of the same year, a newborn creole child was baptized with the same name—the only other time it recurred as a sole name throughout the records. We found nineteen similar cases, in half of which the new name-receiver was another adult, and in the other half newborn children. We have already observed from the account of Andrew the Moor that the Moravians approved of using peers and contemporary figures as namesakes for new converts. Alternatively, it is possible that names shared between adults and children may have been chosen by the slaves themselves, to denote kinship relations among their community.

Among the Christiansted Lutheran Church and Friedensthal records, there are some discernible cases of patronymic and matronymic naming, where all or part of the mother and/or father's names are conferred upon the child, thus marking their genealogical relationship. Among the Lutheran records, we were able to identify twenty children (out of 202 baptisms) who received one or all of their parents’ forenames. Eighteen were boys who received one or all of their father's forenames (five of whom were white men); one was a boy who took part of his mother's name (Lucas Paulus for Eva Paulina); and one was a girl who received her mother's forename. Three of the boys, as well as the girl who shared a forename with her mother, were the children of free women of color and therefore were also born with free status.

Among the Friedensthal Moravian records, we found forty-five children (out of 315 baptisms) who were named for one or both of their parents. By far the largest proportion were boys who were named for their fathers (twenty-nine cases). There were also four girls named for their fathers, eight girls and two boys named for their mothers, and two boys who received parts of their names from both parents. Five of the children were mulattoes, born to an enslaved mother and a white father. In four of these cases the children were named for the father, and in one the child took names from both parents. There were also two children born to free women of color and white men, both of whom were named for their fathers.

A common trend among both these datasets is the higher frequency of children named for their fathers than for their mothers. This is doubtless symptomatic of the vulnerability of relationships in which one or both parents were enslaved, given the perpetual threat of separation, and the couple's limited capacity to maintain the integrity of their family in such circumstances. Indeed, twenty-eight of the examples studied in the Friedensthal records correspond to couples where the parents have differing status (one is enslaved and one free). In many of these cases, the couple was likely to have been living separately, meaning that the children grew up with one parent absent, usually the father, and so patronymic forenames could serve as a link to the absent parent.

The situation is more ambiguous in cases of enslaved children named for a white father (there are five such instances among the urban records). Historically, many such children were the result of sexual abuse of enslaved women, and some scholars have argued that for this reason enslaved families generally avoided using the personal names of white male slave-owners for their own children (Cody Reference Cody1987). On the other hand, attributing the name of a white father to a mulatto child could constitute a bid by the mother for the child's paternity to be recognized, perhaps even inspiring the father to purchase his or her freedom. It is possible that these children were already recognized by their fathers, although this seems a safer guess in the two recorded cases of children born to free women of color and named for white fathers.

Diversity and Individuality

We have remarked that in the Moravian sets, particularly in the early years, the Brethren seem to have influenced the names chosen for converts. At La Grande Princesse in particular they introduced unusual biblical names, creating a pool of around eighty-five to one hundred names that could be used for converts (individually or as composites). In the Lutheran church, by contrast, people undergoing baptism drew from a fairly small pool of around fifty Christian names, though they strung them together to create unique names for themselves and for their children.

In total, fifty-four male forenames and forty-nine female forenames accounted for all the names given to the 251 slaves and free people of color in the Lutheran records. Among these, the most common names for males were Johannes/Johanne/Johan (thirty occurrences), Christian (fifteen), and Fridrich/Frederik (twelve), and for females Maria (forty-two), Anna (thirty-one), and Elisabeth (twenty-four). However, the number of individuals sharing an identical name was reduced by use of double, triple, and even quadruple forenames. Thus, these repertoires of around fifty individual names were recombined in various orders to produce a larger number of unique combinations, resulting in seventy-eight unique male names among a total of 108 entries, and ninety-four unique female names among a total of 143 entries. In the rural Moravian dataset, there is considerable sharing of names: only 112 unique names are found among 821 baptized individuals. In the Lutheran dataset, in contrast, there are 172 unique names among 251 baptized individuals.

This implies that within the enslaved Moravian congregation there was more emphasis on sharing names, perhaps for spiritual or kinship reasons. Among the urban Lutheran congregation, individuals appear to have chosen multiple personal names for themselves and their children as a means of individuation. This is particularly clear among adult converts who changed from a single name to a double or triple name, such as Eva to Anthonetta Lovisa, or Mathilda to Mathilda Carolina Petronella. In doing so, they may have incorporated the names of ancestors or guardians (e.g., godparents, sponsors, or patrons) as a way to mark vertical and horizontal bonds of kinship and community. Another possibility is that the additional names were bestowed upon the baptizees by significant individuals. Cousseau has noted, for instance, that in the neighboring French colonies, as in metropolitan France, godparents were intrinsically involved in choosing children's personal names for the Catholic baptismal rites. Enslaved infants in Martinique received two Christian names, one chosen by each godparent (Reference Cousseau2012: 200).

To summarize, in the Crucian datasets, we note a general tendency toward Christian names and away from African, slave, and diminutive European names. This trend accompanied the creolization of the enslaved population and the dwindling number of African-born individuals, but it can also be seen as an effort to remove the stigmas of slavery by appropriating names used in white society and Christian communities. The Moravians seem to have influenced their slave converts in the names they chose and effected name-changes to mark spiritual conversions, yet over time the changes became less radical, since slaves already had Christian names. These Moravian names may have served to articulate bonds among slaves, whether by linking individuals as spiritual “brethren” or by marking links of genealogical kinship, guardianship, or patronage.

In the urban churches we find more evidence of enslaved individuals and free people of color using baptism as an opportunity to choose their names and those of their children. For instance, we have observed patronymic and matronymic tendencies, used either to bind together families who were vulnerable to separation, or by mothers to make demands upon white fathers. The adoption of multiple personal names in the Lutheran church through baptism may also have been a way to simultaneously mark individuation and (possibly) reference genealogical links across generations, or horizontal bonds with significant contemporary figures.

THREE MICROHISTORIES: DAMA, MERCY, AND HANS JONATHAN

In this section, we follow the trajectories of three individuals from the Danish West Indian context about whom enough historical documentation exists from over the course of their lifetime to allow us to make some comments and inferences about their own uses of names and naming choices. In doing so, we will address the question of whether the enslaved maintained their official/baptism name (or other names) in different social settings or at different life stages through slavery and when gaining freedom. We draw upon the perspective of Zemon Davis (Reference Zemon Davis2011), and the work of Louise Sebro on the Danish West Indies that focuses on “changes in identity in the lives of particular individuals […], attempting to get as close to the issue as possible through a micro-perspective focusing on particular individuals and the ways in which they navigate between different social networks in the Danish West Indies” (Reference Palsson2010: 11).Footnote 7

Our first micro-history is of Dama (d. 1747), a woman born in the Kingdom of Popo (part of present-day Benin), whose case is discussed in some detail in Sebro's study Mellem Afrikaner og kreol: etnisk identitet og social navigation i Dansk Vestindien 1730–1770 (ibid.). Dama was captured around 1699 by slave-hunters and transported to St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies, where she eventually became free and married a free man. In Popo she had been known as Dama, but when she was sold as a plantation slave she was renamed “Marotta.” When she was baptized in the Lutheran fashion in 1737 she was renamed again, as “Madlena.” The shifts from one name to another—from Dama, to Marotta, to Madlena—mirror the shifts from free Popo, to African Caribbean slave, to African Caribbean Christian. To what extent, Sebro asks, were these shifts in name indicative of permanent changes in identity, and to what extent did different identities coexist, depending on context?

Various scholars have put forward evidence to argue that enslaved Africans did not simply accept the slave names given to them in the New World or forget those they received in Africa. Considerable proof of self-naming by the enslaved on St. Croix can be found in both local runaway notices and police records for several plantations (Simonsen Reference Simonsen2017; UNESCO 2017). Historian George Tyson (Reference Tyson2017) has found over ninety examples of aliases being used by enslaved men and women in the runaway notices published in the St. Croix newspapers from 1772 to 1848. His sample includes several African aliases (such as Quamina, Cudjoe, and Waba), at least one of which (Tamba) was stated to be the “country name” of a fourteen-year-old Mandé boy who had fled from the Negro Bay estate and twice escaped the hunters sent after him. Alternatively, African names may have been remembered, even when they were rarely used. This point was attested to by Cudjo Lewis, who stated that it was only in moments of personal prayer that he saw himself as being “called” by his “name from cross de water”: Kossula.

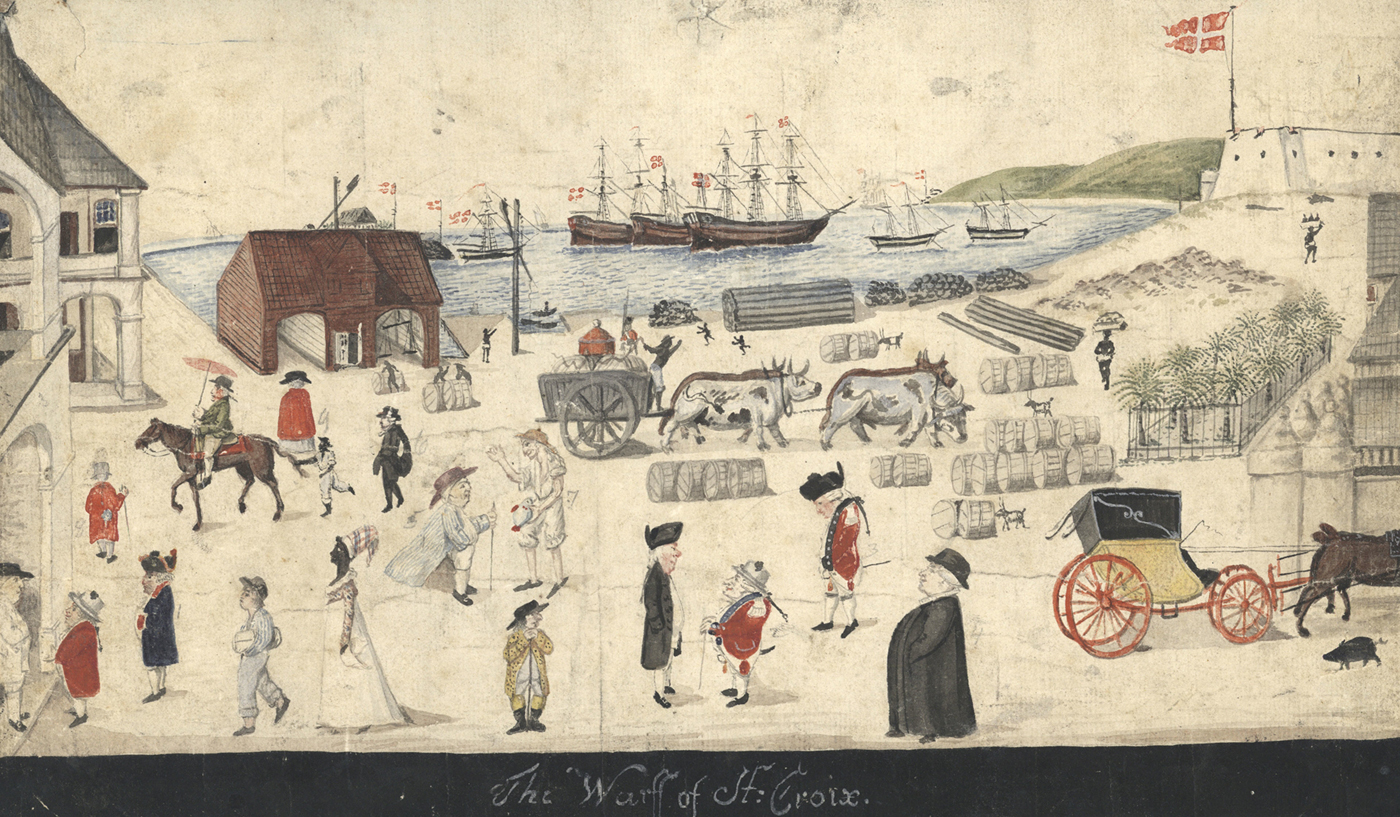

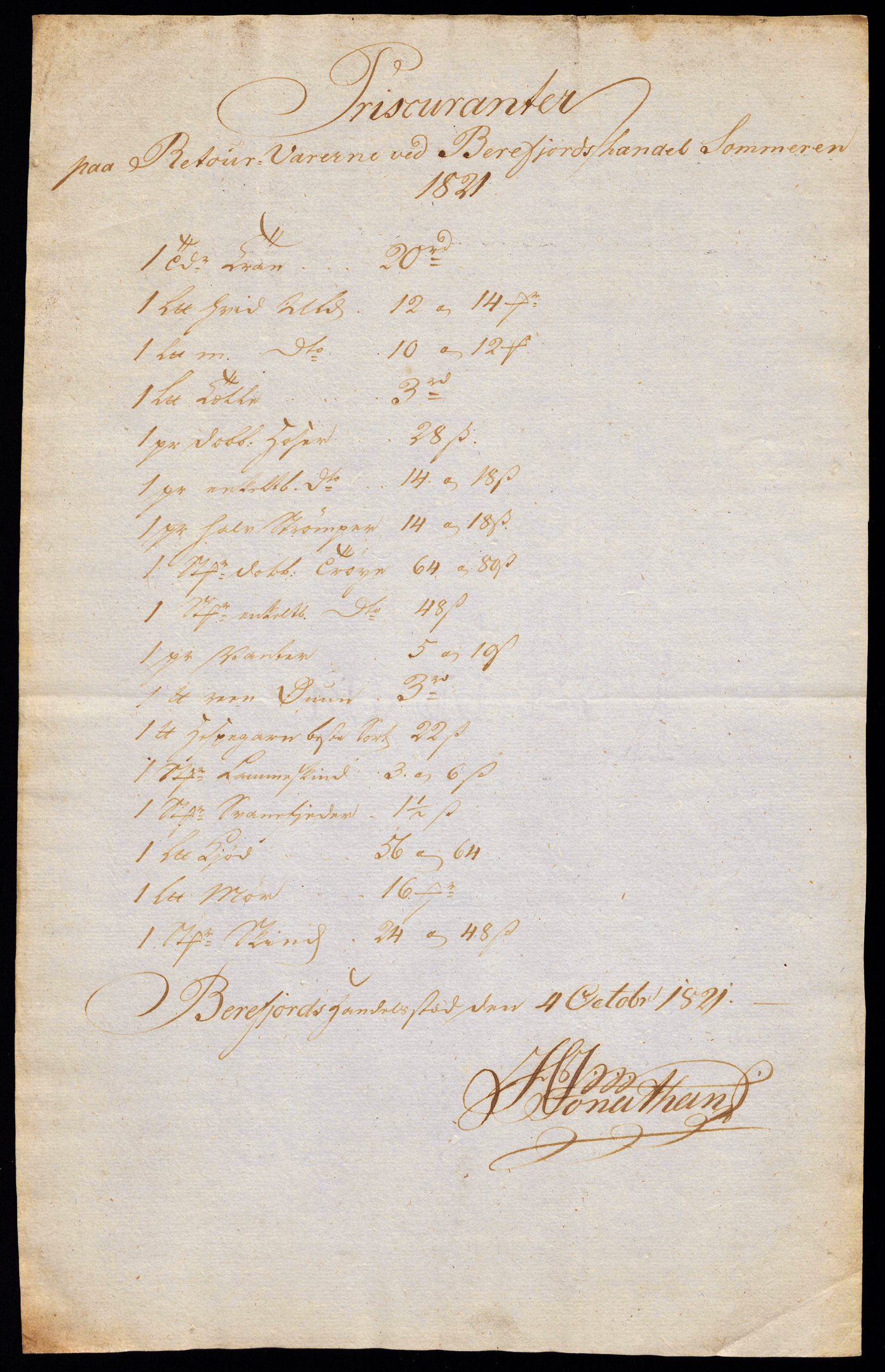

Dama, too, continued to identify herself using both her original name and her slave name after being freed and baptized. As Sebro recounts, she wrote a significant and unique letter in 1739, addressed to Queen Sophie Magdalene and requesting further religious instruction on how to serve “Lord Jesus” (Reference Sebro2010: 51). The letter had two versions, one in Gbe (a West African language), which was signed “Dama,” and one in Dutch-Creole that was signed “Marotta, now Madlena from Popo in Africa” (image 3). The cohabitation of these three names in two simultaneously drafted letters suggests that, despite the emphasis many Europeans placed on the permanent transition that baptism signified, for Africans in the colonies this name could continue to coexist with others they had been given throughout their life course. Dama/Marotta/Madlena is a case in point; in Sebro's words: “Marotta and Madlena were simply layers number two and three in her identity.… This was not just a question of different parts of her identity, the different parts were interwoven with different parts of her life and the different spheres they represented—spheres related to, respectively, the African and the Creole aspects of her life” (ibid.: 201).

Image 3. Madlena's letter, in Gbe (left) and Dutch Creole (right). UA R15Ba3nr. 61. Schreiben von 250 Negern an der Königin. Courtesy of the National Archives of Denmark, Copenhagen.

Image 4. Hans Jonathan's signature, from the records of the store of Djúpivogur, East Iceland. Courtesy of the National Archives, Reykjavik.

Thus, signing the African and the Dutch-Creole versions of her letter in different fashions did not necessarily signify that the writer was in a transition phase. Instead, as Sebro submits, she may have used different names for different social spheres, possibly navigating between different identities depending on context:

Damma was not mentioned in the same context as Marotta and Madlena.Footnote 8 … In other words, she used the name Damma when she expressed herself by means of her native language Gbe which she brought from Africa. Since the Gbe version of the letter in all probability was formulated by herself, one has to conclude that Damma was a name that she felt strongly attached to, so strongly that the identity survived many years of inhabiting the Creole sphere where she was known by the name of Marotta (ibid.).

At the same time, it is important to highlight the particular context and register in which Dama/Marotta/Madlena was identifying herself in this example. This is an interesting and rare case of an ex-slave identifying herself formally using her various given names, in a written register. In doing so, she acknowledges the importance of name-giving as a means of making oneself identifiable to the state within the colonial and metropolitan bureaucracies. In the absence of a formal surname, her self-identification as “Marotta, now Madlena from Popo in Africa” may also be understood as a means of ensuring her own recognition by the state as a legal personality whose claims had to be taken seriously.

Our second case is of another African-born woman, Mercy, whose transition from enslavement to petty entrepreneur, free property owner, wife, and widow is documented in a series of name changes recorded primarily in the remarkably complete set of land and head tax registers (“Matrikler”) that exist for the island of St. Croix from 1754 to 1916.Footnote 9 These important records are largely untapped sources of information about naming practices in this Caribbean sugar colony. Mercy's story not only demonstrates the importance of property tax records for investigating naming practices in New World slave societies, but also clearly reflects the persistence of West African name shifting to mark personal social transitions in this highly typical Caribbean slave society.

“Mersie” first appears in the Crucian historical records in 1755 as an enslaved female on an unnamed sugar plantation in the West End Quarter of St. Croix. She was freed by her owner George Wade on 19 May 1756, and subsequently received her official free letter on 18 June 1764. Later sources identify her as an African. Her actual free letter has not been located and probably no longer exists. In 1772, identified as the free black woman “Mercy,” she appears for the first time in the land tax registers as living in the recently established port town of Frederiksted, situated on the island's western shoreline.

In 1777, under the new name Mary Wade, she acquired a vacant lot at 39 Hospital Street in Frederiksted, where she built a house.Footnote 10 This property is near the center of what became known as the “Free Gut” area of Frederiksted because it housed a large percentage of the town's free colored population. Between 1778 and 1785, identified variously as Mercy Wade, Mary Wade, or Maria Wade in the land tax and free colored registers, she lived on her Hospital Street property with her daughter Molly Wade and from one to four persons enslaved to her. In 1780, she acquired eight additional vacant lots in the Free Gut section, making her the largest free colored landowner in Frederiksted during the last quarter of the century.

It is not completely clear how Mercy/Mary managed to secure these properties. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century she appeared frequently in probate records as a baker and a caterer at the funerals of leading government officials and planters, for which she received remuneration. Clearly, she was well regarded in elite circles and she must have used those contacts to her advantage. Nineteenth-century sources classify her as a seller, huckster, and seamstress. On several invoices that she submitted to probate proceedings she alternatively named herself either Mercy or Mary Wade (and signed with an X), which strongly indicates that she and not bureaucratic officials provided the names that appear on her property and tax records.

In 1783, she sold one of her vacant parcels and used the proceeds to build a house on 30 Hospital Street, which she initially rented out. Three years later she moved into this house with her daughter Molly. Joining them was Lorentz Hendrichsen, alias Polidore/Polydore, a black barber who had been freed by planter and Frederiksted merchant Cornelius Hendrichsen in 1781. In 1787, Mercy married Lorentz and the couple moved into her house at 39 Hospital Street. No marriage record exists, but Mercy's new status was reflected in the land tax registers wherein she regularly appeared under the name Mary Hendrichsen, from 1787 until 1802. During that period, her husband Laurence/Lorentz was listed as sole owner of the Hospital Street properties and co-owner with Mary of properties on nearby La Grange Street (today named Fisher Street).

Starting in 1803, there were signs of financial and possibly marital troubles. In that year Mercy/Mary reclaimed the name “Mary Wade” along with sole ownership of 28-29-30 Hospital Street and her former property on La Grange Street. Her husband Lorentz Hendrichsen was listed as the sole owner of 39 Hospital Street, along with a handful of slaves. By 1807, he was no longer a slave-owner. From 1804 to 1806, the couple was recorded as living apart, with Lorentz on 39 Hospital Street and Mary Wade at 30 Hospital Street. In 1808, a property on New Street was sold. A year later, Lorentz Hendrichsen transferred 39 Hospital Street to the ownership of free mulatto Richard Mardenbrough of Christiansted. In 1810, Mary Wade yielded 30 Hospital Street to the same man.

In 1815 and 1821, Lorentz Hendrichsen and his wife, identifying herself as Mercy Lawrence, were once again living together at 39 Hospital Street. By 1824, Lorentz must have died since he was not recorded in either of two Frederiksted censuses prepared that year. Those censuses also reveal that widowhood prompted another name change for Mercy, who was now identified as Cathrine Lawrence in one of the censuses and Kitty Lawrence in the other and described as living at 30 Hospital Street and employed as a seller. In the Frederiksted Free Colored census of 1831–1832, she was identified as Cathrine Lorentz, an African belonging to the Anglican Church.

In 1837, Cathrine Lawrence regained ownership of 30 Hospital Street, where she continued to live for the remainder of her long life. She also seems to have retained the name Cathrine Lawrence, by which she was designated in the 1841 and 1846 censuses, as well as on her death record, dated 2 January 1850, which specified that she was buried in the St. Paul Anglican Church cemetery, just down the street from her home. To others, though, she seems to be have been known by both names. The Frederiksted census of October 1850 showed 30 Hospital Street as belonging to the heirs of “Katy Mercy,” and town Sheriff Carl Sarauw also recorded “Katy Mercy's heirs” as the owners of the property in 1850, identifying “Katy Mercy” as owner and resident in 1849.

Like Dama's case, Mercy's compelling story of resilience and achievement appears to offer a striking example of the persistence of the West African customs of name shifting and name switching among African free people of color in Caribbean slave societies. In this case, new names were taken on to mark significant events in Mercy's life (e.g., the acquisition of her first property, marriage, and widowhood). While no written record of Mercy's African name has been found, her appropriation of European/Christian names—which she used to identify herself formally before the colonial administration, and by which she was apparently informally known among peers, who used the familiar, diminutive forms of these names—supports the idea that the giving and taking of European names among free people of color was not necessarily a sign of domination, but could be the result of strategic and personal choices. In addition, the names provided by Mercy/Mary/Cathrine in legal and census records reflect her usage of certain European naming conventions that were salient in Crucian society, such as the adoption of her husband's chosen first name, Lorentz/Lawrence, as a family name at different points in her life, particularly following his death. This practice underscores further the flexible and pragmatic uses of hegemonic naming conventions among free African creoles in colonial society.

Our third case involves a man named Hans Jonathan (1784–1827) whose life has been traced at different points in a recent biography, The Man Who Stole Himself (Palsson Reference Palsson2016). Hans Jonathan was born in 1784 on St. Croix to a house slave called Regina (later baptized in the Lutheran Church as “Amalia Regina”). Her son's name appears among the Christiansted Lutheran Church baptismal records alongside the labels “mulatto” and “illegitimate,” and a note stating that his father was “said to be the Secretary.” This unknown white man was probably a Dane named Hans Gram, who worked on the Schimmelmann plantation, but soon left for Boston where he established his name as a musician.

As a young boy of seven or eight, Hans Jonathan was taken to Copenhagen to rejoin his mother (who had been sent there a few years earlier) and his masters, Ludvig and Henrietta Schimmelmann, and spent most of the next decade there. In 1802, at age seventeen, after receiving a beating from his mistress, and distinguishing himself in the Battle of Copenhagen, Hans Jonathan ran away, claiming freedom with the support of a Danish navy official and the acting King of Denmark. Henrietta Schimmelmann brought Hans Jonathan to court over the claim and won, but rather than returning to being her slave he fled to Iceland in 1802. There he found work as a store clerk, married an Icelandic woman named Katrín Antoníusdóttir, with whom he had a son and a daughter, and died in 1827 at the age of forty-three, most likely of a cerebral hemorrhage.

In his time in East Iceland Hans Jonathan became a well-liked member of the local community of Djúpivogur where he lived and worked. His name appears a handful of times in letters of visitors to the region who made his acquaintance, as well as in official documents (e.g., his marriage certificate and the legal statement of his assets following his death). At no point, it seems, did Hans Jonathan attempt to change his name, even to conceal his identity from Danish officials (ibid.: 149–50). His name is flagged by his elegant signature on several sheets from the Danish store where he worked (image 4). Perhaps he felt safe in the distant post of Djúpivogur at a time of slackened relations between Copenhagen and Iceland in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars. Then again, as a literate creole who had spent much of his life in metropolitan Copenhagen and distinguished himself as a soldier of the Danish Crown, he may have been proud and defiant about maintaining his name despite the threat of being returned to his mistress. Alternatively, as Frederick Douglass once expressed, he may have felt the need to hold on to his given name, “to preserve a sense of identity” (Reference Douglass1992 [1845]: 99).

The names that Katrín and Hans Jonathan gave to their children suggest that they were indeed proud of Hans Jonathan's name. There are clues that they used this as an opportunity to reaffirm kinship links with family members he had left behind through exile. For instance, they chose to name their daughter Hansína Regína—a name that establishes a double genealogical link by use of one of Hans Jonathan's own forenames (which was also perhaps that of the girl's grandfather, if Hans Jonathan was named for Hans Gram), and that of his mother, Amalia Regina. Hans Jonathan's wife and children also took “Jonathan” as a family name, and in some local records he is referred to as “Jonathan,” in the Danish fashion—after all, the locals considered him a Dane. His grandchildren and their descendants, however, have since used patronyms derived from the father's first name, in the standard Icelandic tradition, instead of family names. Thus, the children of Hans Jonathan's son, Lúðvík, would have been called “Lúðvíksson” and “Lúðvíksdóttir.”Footnote 11

Although the life trajectories of Dama, Mercy, and Hans Jonathan through slavery and from slavery to freedom may be exceptional, their stories offer evidence that, at least in some cases, and in spite of the symbolic violence underlying the imposition of European “Christian” names, such names were also appropriated and chosen by enslaved people as tools for asserting their individuality and for marking the bonds of kinship that they were formally denied. In addition, the cases of Mercy and Dama indicate that these transcultural practices were by no means restricted to those who are traditionally thought of as “creoles” (i.e., individuals born in the colonies); on the contrary, hybrid naming practices were used in complex ways by African-born individuals, particularly those who managed to make the legal transition from enslavement to freedom.

CONCLUSIONS

In most cases, naming helps articulate family connections, citizenship, and belonging. Practices of naming represent a form of biopolitics, a technology of the self, in Foucault's sense (Reference Foucault, Martin, Gutman and Hutton1988). A name that endures and “sticks” is founded on a tacit consensus about the name givers’ right to name and the legitimacy of the name itself. Namers and the names they establish are inseparable from the community in which they are embedded. In slavery, however, naming is largely a one-sided act, either purely for identification purposes or for denigration, for imposing social death by severing earlier social networks and forging new ones.

During and after the Middle Passage, slaveholders were usually keen to rename their slaves, often with names not unlike those applied to livestock, and indeed, slaves were considered “chattel.” Since the African forebears of Afro-Caribbeans subscribed to “a kind of magical nominalism, whereby the substance of a person is believed to inhere in his or her name” (Burton Reference Burton1999: 54), it has been thought that with renaming under the conditions of slavery this “substance” was threatened if not destroyed. The slaves were deformed with the new name, torn from their former social environment: not only was the former persona of the slave eradicated, but the slave was “marked off from other persons whose social identities are given privileged recognition” (Benson Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006: 181).

As we have seen, the names given to Africans in the slave societies of the New World were diligently recorded and inscribed in a range of administrative, legal, clerical, and private records: bills of sale, plantation inventories, auction lists, court records, public announcements of runaway slaves, wills, baptism records, and manumission certificates, to name but a handful. These administrative records are sometimes overwhelming, which makes it a challenge to track individuals who were potentially renamed more than once over their lifetimes, particularly since most enslaved individuals were unable to pen accounts of their own experiences. In recent decades, however, historians and genealogists have attempted to read these sources against the grain and piece together micro-historical accounts of their accomplishments and lived experiences. Here we have only scratched the surface by using a few sources from one of the best documented slave societies in the New World.

Such efforts constitute an attempt to re-envision the enslaved as historical actors, investing them with a sense of agency, and repositioning them within family structures and social networks. Sometimes slaves were able to negotiate their networks and the cultural landscapes in which they were embedded, thereby resisting social death and refashioning their names and themselves. Social death, then, may have been partial. Drawing upon life histories and historiographical accounts of slavery in the Danish West Indies and the official and theological roles played by Lutheran and Moravian missionaries in St. Croix society, we have outlined and contextualized the local patterns of naming, exploring the onomastic conventions, social strategies, and cultural transitions that may explain and underpin these trends.

Name pluralism is common in many contexts, for instance among Canadian Inuit, where Euro-American surnames and customary names coexist, their use depending on context. The complex social network that forms an Inuk's person is constituted through names (Palsson Reference Palsson2014). Names are said to create personality, particularly through their combination: “We are talking about multiple personal essences; you are not simply playing different persons; you are different persons” (Bodenhorn Reference Bodenhorn, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006: 151). Often when slaves gained their freedom they insisted upon receiving a new name in front of witnesses at a formal event, to mark the ending of oppression and the birth of a new person. In this account, we have focused on baptisms as a ritual that could signal an important social transition, including the regaining of a certain dignity (e.g., by replacing slave names with “Christian” ones) and a public confirmation of the individual's entry into new community with specific rights and privileges. The baptism of children presented an opportunity for slaves to name and be named anew, facilitating continuity and the creation of intergenerational links. These records also allow historians to track processes of creolization and social change.

Sometimes, slave names coexisted with both new and old names. Durand and Logossah have pointed out that in several West African traditions name changes are used habitually to mark social transitions or shifts in social status. Among the Toucouleur, slave names can even be preferred as a mode of designation “to show that this period is ‘a parenthesis’ in their lives, and therefore unworthy of interest, unreal” (Reference Durand and Logossah2002: 136–37). European bureaucratic conventions also allow for the coexistence of formal and given names, a custom that free Africans such as Dama and Mercy adopted pragmatically to support various legal claims for which colonial officials and the metropolitan state had to recognize them. Alternatively, the case of Hans Jonathan indicates that many creoles born in the colonies may only have known or used one name, usually drawn from the repertoire of the hegemonic Christian culture. These designations have since been labeled by black and Afrocentric movements as “slave names”—a sign of the lingering cultural subjugation of African-descendants to Eurocentric norms (e.g., Haley and X Reference Haley and Malcolm1999: 203; Benson Reference Benson, vom Bruck and Bodenhorn2006: 196–97). Yet, Hans Jonathan's example shows that they could also be a meaningful anchor for personal identity, as well as a means of commemorating kinship ties with black family members following enforced and even permanent separations.

Since detailed microhistories that show practices of naming and renaming over an individual's life course are still rare and greatly contingent on the historical sources available, the extent of these practices in the Danish West Indies and elsewhere in the diaspora remains undocumented. Such accounts may help to establish connections that tend to get lost in aggregate analyses and macrohistories. For instance, detailed research on a specific household may reveal that several names refer to the same person. It seems important for advancing the study of names in slavery to experiment with research methodologies that fruitfully bring together the levels of households, plantations, colonies, and empires.