The end of World War I is generally considered a triumph of national independence movements and the entrenchment of national self-determination in its Wilsonian and Soviet versions after the destruction of Eurasian empires, including the Russian and Ottoman empires. The consequent interwar years saw the emergence of new national polities and mandate regimes in their stead that pursued modernization marked by beliefs in progress, universalism, and a Eurocentric global diffusion of developmentalism. Old forms of non-Western and imperial governance were renounced, together with ideas of fundamentally incomparable civilizations, and replaced by the advance of self-determination and modernization. This meant that peoples and peripheries previously considered uncivilized, or incapable of self-determination could now follow the path of Western metropoles to achieve equality, at least on paper. Newly emergent nations everywhere sought to legitimize their position by following the established national cultures, politics, and technologies of their more developed peers.

History is more complex than this established narrative. The narrative emphasizing discontinuity and transition between empire and nation, while reifying the familiar divide and comparisons between the East and the West, or the North and the South, overlooks a much more complex story of knowledge diffusion, appropriation, and nation-making on the basis of networks and actors that were not yet bound by the new world order emerging in the war’s aftermath. Our puzzle is a story that is almost antithetical in many ways, yet which runs along the grain and navigates through these developments. It shows that the end of empire was not the end of inter-imperial networks and knowledge diffusion. The newly established Turkish republic was equally pursuing all the above developments and sought models from Western ideas of republicanism, national self-determination, and modernization of the country, but also from elsewhere. One of the most popular examples of developmentalism in Turkey, through the interwar years and up until today, turns its gaze from a utopian future toward the undeveloped past, from Western metropoles toward the Russian periphery, and from top-down modernization toward grassroots development.

The 1928 book The Country of White Lilies is about a Russian imperial periphery, and provides a narrative of Finnish national development through its author Grigori Petrov’s travels and political vision (Petrov Reference Petrov1928). It quickly became popular in Turkey and has remained an important part of its political bibliography and imaginary ever since.Footnote 1 The Ministry of Education eagerly adopted it for teaching prospective teachers, and in the 1930s it was made mandatory reading in military schools as an example of national development to be followed for the Turkish nation-building project (Taner Reference Taner and Petrov1960).

The story of the book’s journey poses an interesting political, spatial, and temporal puzzle for the sociology of empires, nationalism, and knowledge diffusion within the global power structure: How did a peripheral duchy of the Russian Empire, the Grand Duchy of Finland, become a model for social organization and national development in the post-Ottoman Turkey of the 1930s and 1940s? How did a book produced in the context of contestations within the Russian imperial political field move across imperial and post-imperial spaces to become a non-controversial node in the Turkish nationalist project?

Mainstream sociological theorizing about the diffusion of developmental and nation-making techniques and models falls short of explaining the celebration of the Grand Duchy of Finland in Turkish political imagination. Developmental projects and political models of non-Western spaces are often subsumed under ambiguous and West-centric terms, such as “Westernization” and “modernization.” Instead, “We should … begin to think beyond these images to examine the positive processes going on in the space ‘between’—not the assumed void, but an arena of intense contestation between a panoply of forces, actors, and places” (Mikhail and Philliou Reference Mikhail and Philliou2012: 743). Nationalism’s embeddedness within empire and imperial logics continued after the war, and the construction of the idea of a dichotomy between nation and empire required a lot of political, intellectual labor and time in the context of the postwar reorganization of global political space and topographies of power. Various configurations of international and transnational knowledge networks existed across non-Western empires, their post-imperial spaces, and their peripheries and metropoles.

In the case of The Country of White Lilies, the periphery of the Russian Empire presented itself as a source of knowledge innovation and an object of appropriation for a post-imperial metropole refashioning itself as an anti-Ottoman nation-state (Philliou Reference Philliou2011; Adak Reference Adak2003). The Finnish national development model as portrayed by Petrov was adopted as a case of successful nation-state making in Turkey, and became part of the project to reject empire, which was cast as the opposite of national development. In effect, through the book, a model of successful colonial development in the periphery of a pre-1918 non-Western empire was adopted by a post-imperial metropole of another non-Western empire as a model for nation-state building. Furthermore, the logics of knowledge transfer cut historically across temporalities, spaces, and imperial differences of the past perceived at the time, differences that were themselves in the process of being remade. Hence, the Grand Duchy of Finland’s national development from 1810 was spatially and temporally displaced from its imperial context onto postwar Finnish and Turkish nation-state building. To understand the reception of and fascination with this particular peripheral model in post-Ottoman Turkey in the uncertain interwar years, we need to unpack the temporal and spatial entanglements of different national and imperial logics across two land-based empires. We must rethink how questions of decolonization, dependency, race, nationalism, freedom, and development traveled across inter-imperial spaces and temporalities while shifting in meaning.

Next, we outline our approach for how to go about unpacking and rethinking these questions by moving beyond a simple metropole-periphery division. Then, we briefly introduce Petrov’s books’ contents and national developmental vision. We describe the national development of the Grand Duchy of Finland under the Russian Empire and the making of political independence of Finland after the Great War, comparing them with Petrov’s portrayal of the imperial periphery. In the following section, we focus on the book’s movement across inter-, intra-, and post-imperial spaces. We then analyze its enthusiastic reception in Turkey as a viable model for national development, emphasizing the comparisons readers drew between the geopolitical positions of Turkey and Finland, including the factors of imperial oppression and racial kinship. We then introduce relevant theoretical and methodological debates within the sociology of empires and nation-building and develop our inter-imperial approach based on the case of The Country of White Lilies. We build on Laura Doyle’s (Reference Doyle2014) concept of “inter-imperiality” and Monika Krause’s (Reference Krause2021) call for conducting research outside of paradigmatic “model cases.” We conclude the paper by suggesting an alternative temporal, spatial, and political approach to post-World War I knowledge diffusion and nation-building projects that does not analytically privilege Western imperial spaces and avoids reifying entrenched binary categories such as East versus West, tradition versus modernization, and empire versus nation.

Beyond the Metropole-Periphery Divide

We approach The Country of White Lilies and its reception by making three analytical shifts that reveal overlooked dynamics of global imperial politics of the era, and global flows of knowledge and discourses not bounded by established Western imperial formations. First, focusing on Petrov’s book’s movement allows us to shift the analytical focus away from sovereign structures and their spatial limits to highlight networks of individuals and imperial/national politics that are held together by the object, thus challenging nationally or imperially contained narratives. Sociology of empires tends to focus on intra-imperial governance structures, metropole-periphery knowledge flows and comparisons, or comparisons of metropoles with each other. We will argue that following the book’s inter-imperial journey lets us adopt a lens on the politics of development and global recognition that brings into focus the configuration of varieties of inter- and intra-imperial interactions. We examine the book’s production within the field of Russian imperial politics and its adoption as a peripheral nation-making model in the post-Ottoman metropole. This complicates linear understandings of temporality by displacing a particular peripheral context in the early and mid-nineteenth century to the early twentieth century. It also allows us to think about temporality not as a linear, objective passage of time, but as a dynamic experience that actors themselves define and displace onto different political objectives in different spaces and periods.

Second, we relegate the Western imperial formations to the background of the narrative and focus on the interactions of the different projects of the (post)Russian and (post)Ottoman spaces, which allows us to theorize from outside of Western agency. Sociologist Fatma Müge Göçek (Reference Göçek and Go2013) has suggested focusing on marginalized or forgotten cases as alternative sites of knowledge production beyond “West and the rest” comparisons. While we concentrate on just such a case, we refrain from conceptualizing the Ottoman and Russian empires as “in-between” the colonizer and the colonized, as Göçek does, since this approach perpetuates a dichotomy, particularly a spatial one, between the East and the West. Moreover, defining the territories of the Ottoman and Russian empires as outside of the “West” was, and remains, a politically contested and constructed move, and their positions in the global arena shifted throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (e.g., Minawi Reference Minawi2016). This constant redefinition alerts us to the fact that these categories themselves should be analyzed rather than applied as analytical categories at the outset. Viewing global politics from outside the East-West dichotomy and through the lens of inter-imperial positionality (Doyle Reference Doyle2014) reveals overlooked networks of relationships and knowledge diffusion. In this sense, we are seeking not to provincialize any location (Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2008), but rather to trace knowledge networks and trans-imperial and trans-historical political connections.

Third, by spotlighting the movement and reception of The Country of White Lilies, coupled with an analysis of Finnish national development and imperial politics, we gain insights into what terms like independence, dependency, nationalism, and Westernization meant to different actors, and how they were appropriated and were temporally and spatially displaced onto different political projects, spaces, and political imaginations. Tracing such shifts in meaning illuminates the global politics of the era and how actors in different times with different political projects appropriated such terms to rethink past imperial histories. For example, what work did the kind of developmental paradigm described in Petrov’s book do in terms of the Turkish national project? This helps us think self-reflexively (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu2004) about our own understanding of the postwar period with regards to the appropriations of our own era.

Petrov’s Book as an Itinerant Object

Due to his controversial political beliefs, Grigori Petrov went into exile from Russia to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, where he published The Country of White Lilies in 1923. A Bulgarian edition came out in 1925 and became a success there. By 1928 the book had been translated into Turkish and again became a hit, especially among educators who pursued the Turkish nationalist project after the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Subsequently, from the Turkish edition it was translated into Arabic. Ironically, it was not translated into either Finnish or Russian until quite recently when the original manuscript was rediscovered, and the book’s success was confined to the post-Ottoman lands. Its reception in Turkey poses an even more interesting puzzle than its reception in other post-Ottoman spaces. Post-Ottoman Turkey was the direct inheritor of the Ottoman metropolitan imperial state institutions, and at first glance, one would expect the book’s focus on the peripheral development of the Grand Duchy of Finland under the Russian Empire to have resonated more in peripheral Ottoman regions. Furthermore, unlike travelogues and treatises proliferating in Turkey at the time—such as Falih Rıfkı Atay’s Taymıs Kıyıları (Reference Atay1934) (The shores of Thames) and Tuna Kıyıları (Reference Atay1938) (Shores of the Danube), or Selim Sırrı Tarcan’s Şimal’in Üç İrfan Diyarı: Finlandiya, İsveç, Danimarka (Reference Tarcan1940) (Three lands of knowledge in the north: Finland, Sweden, Denmark)Footnote 2—The Country of White Lilies became popular as soon as it was published, quickly went through several editions, and was adopted for teaching. It remains popular to this day.

The book opens with the imagery of the Russian State Theatre, which was falling apart because its wooden foundation had been neglected for many years. The architects tasked with dealing with the danger the building posed decided that, rather than destroying it they would renew the foundation, gradually and carefully. Petrov draws an analogy between this situation and the development of nations. If enlightened intellectuals and statesmen carefully cultivated the people’s education and self-governance, the nation’s foundation and developmental level would be strong. Petrov then compares the approaches of Thomas Carlyle and Leo Tolstoy to the relationships between great men and their nations.

Petrov writes that, for Carlyle, heroes imbued with a specific morality and strength of character make the history of their nations. Tolstoy, on the other hand, argues that the movement of the people of a nation is what provides the dynamism and success of the “hero.” Petrov asks why these views should be mutually exclusive such that we must choose between them. For him, the two writers reveal two sides of the same truth. “Every great man of the nation is like a magnifying glass. They gather in their personality the strength and superiorities of the nation, and with this they light the souls of millions of people. But if the weather is cloudy, lacking the rays of the sun, then no magnifying glass could be enough for melting one snowflake, heating one drop of water” (Reference Petrov1960: 20).Footnote 3

Upon this thought, he introduces Finland with two important characteristics: it did not have its own independent state until 1917, and this nation had not autonomously produced great men that stood only upon the ground of the nation. The explanation for the cultural and national development of the Finns, then, was not a state structure or exceptional men; rather, it was the result of “every member of the nation working without rest or stopping” (ibid.: 25). What fascinated Petrov about the Grand Duchy of Finland during his travels is that, for him, the small nation had achieved a level of civilizational and cultural development without natural resources, in a notoriously swampy and desolate landscape, only by the enlightening presence of intellectuals teaching the Finnish peasants that they were Finns and that they could achieve great prosperity and development if they worked together to develop the nation from the ground up, starting from dispositional habits like the cleanliness of their homes and politeness toward their neighbors.

The rest of the book consists of Petrov’s imagined lectures of the Finnish politician Snellman and other intellectuals, and stories in which teachers, doctors, and intellectuals with enlightened visions sacrifice their time and effort to uplift other members of the nation to achieve a superior level of civilization. The barracks of the nation are oriented toward educating the peasants and teaching them that all citizens depend on each other, whereas teachers and doctors travel across villages in the service of the people. The development of the Finnish nation, for Petrov, is based on the individual enlightenment and functional interdependence of each member of the nation, reminiscent of a Durkheimian approach to solidarity, achieved through the mobilization of intellectuals in civil society. Petrov claims that this attitude quickly bore fruit, and the swampy and desolate bogs were turned into a bountiful agricultural land where white lilies grow everywhere—a biblical imagery of achieving the near-impossible. Petrov praises “the collective patriotism and selfless efforts of the Finnish intellectuals, priests, youth, and people to revive the Finish [original spelling] nation and salvage it from idyllic poverty.” He celebrates “Finns and their national awakening, the free air of rural Finland and the freedom-loving Finns as opposed to the corrupt air of St. Petersburg” (Gürpınar Reference Gürpınar2013: 230).

By the time Petrov wrote his book in 1923, Finland had gained political independence. He projected this independence back in time, culminating in a linear national development story that eschewed the imperial context and posed political independence as a logical outcome of such mobilization of the intelligentsia. The book’s timeline begins from about 1810s and depicts developments that took place in a colonial and peripheral Duchy of the Russian Empire. We now turn to the Finnish historiography of the period to compare Petrov’s imagination of Finnish development with the development of the Grand Duchy under the Russian Empire.

Imperial Nationalism: From The Country of White Lilies to the Grand Duchy of Finland

The Country of White Lilies portrays an idealized image of development and nation-building in a poor imperial periphery with no proper state intervention. How does the image Petrov paints relate to a picture of the Grand Duchy’s historical developments based on Finnish historiography? Petrov’s story omits the imperial context of Finland’s national development and disregards the establishment of universal suffrage as significant aspects of this developmental model.

Finland had indeed developed the beginnings of what was to be termed a “national awakening” by the mid-nineteenth century. On the heels of the Russian Revolution of 1905, in 1906 the Grand Duchy was allowed to form a unicameral parliament, based on universal suffrage with women also standing for election. It was Europe’s most democratic system at that time: “Retained and reshaped in 1906 the traditional logic of [Russian] imperial sovereignty helped quite paradoxically to achieve universal suffrage in the reformed Sejm of the Grand Duchy of Finland” (Semyonov Reference Semyonov2020: 32).

These developments took place in a peripheral position under the Russian imperial regime when the Grand Duchy was one of the poorest states in Europe. Finnish national awakening and democratization was keenly linked to guaranteeing autonomy and a favorable position in the empire, a pursuit in which the Finns understood the Grand Duchy’s position within a global context of various intra- and inter-imperial relations. A stark discontinuity emerged in 1919 when the colonial Finnish state, after several efforts to avoid it, turned toward national independence as defined by the League of Nations. Considering the Finnish example, historian Alexander Semyonov suggests, “The idea that western European countries by the early twentieth century had a working democratic government thanks to the formation of [the] nation-state in the metropole of the colonial empire needs to be reconsidered together with the idea of symbiotic relations between nation and democracy” (ibid.: 37).

Retrospectively, democratization in the Grand Duchy has been connected to Western European democratization as an early exception of a natural democratic development originating from the West. This perspective originated from a politically motivated portrayal in the West of the pre-independence Grand Duchy as civilizationally superior to Russia, a depiction intended to highlight the brutality and backwardness of the Russian Empire (Korhonen Reference Korhonen2019; Ruotsila Reference Ruotsila2005; Halmesvirta Reference Halmesvirta1990). Such an image avoids explaining why and how a democratic colonial state developed in a poor periphery of the Russian Empire.

After the Great War, democracy came to be connected with nation-states, a view much transformed from the pre-1918 ideas of democratization and national development within empires. This limited further democratization in Finland itself up until 1945: political participation by the left remained restricted, national security took center stage, parliamentarism lost ground to a strong executive institution, and fewer women were voted into parliament. In a nutshell, the Petrovian model of idealized, depoliticized development in colonial Finland was no longer applicable in the independent Finnish Republic, if indeed it ever was in the Grand Duchy. At the same time, nationalist historiography, written and imagined in the aftermath of the Finnish civil war in the 1920s, falsely portrays independence from Russia as the culmination of Finland’s national awakening and democratization.

The narrative crafted after 1919 tells us that the Russian annexation of Finland in 1809 as a semi-autonomous Grand Duchy granted Finland state independence. This led to a natural and singular trajectory of development during which the Finns learned to govern themselves and thereby fulfilled the Wilsonian requirements for self-determination, including racialized civilizational development. American commentators, including President Woodrow Wilson, had initially found the Finns to be racially unsuited for self-determination (Korhonen Reference Korhonen2019). But with the recognition of Finland’s independence, the Finns were suddenly categorized as a race that had “gone through every cycle that the world could demand in political evolution, to the point of an independent people” (United States Department of State 1946, 359). This spoke to wider shifts in global and imperial racialized politics that were aligning with newly emergent ideas of national sovereignty.

However, the idea of state independence was initially developed by Finnish political actors across the spectrum at the turn of the twentieth century. They aimed to secure self-determination and an advantageous position within the Russian Empire, as good imperial subjects—as a separate state equally governed by the Tsar. This contradicts the later national history that has portrayed state independence as a conscious national effort toward full national independence as in the post-World War I model.

If we consider the retrospective national narrative that Russian actions in 1809 set Finland on a path to independence, we should at least ask how and why the empire fostered Finnish autonomy and democratization? And why, then, did Finnish political actors seek a new sovereign after the Tsar’s abdication? P. E. Svinhufvud, for example, a bourgeois politician and perhaps the greatest champion of Finnish independence in the traditional nationalist historiography, stated just six months after he had declared Finland independent from Soviet Russia that a constitutional monarchy with a German king was the “only form of government for Finland.”Footnote 4 This was no surprise to Finnish politicians, since the previous November, Svinhufvud, before declaring independence, had advised his colleagues, “Just get the Germans here, otherwise we won’t manage” (Klinge Reference Klinge1990: 15, cited in Kuisma Reference Kuisma2010: 76). As Kuisma puts it, “Finland in early summer of 1918 was a German vassal state, whether it wanted it or not” (ibid.: 81). This exemplifies how Finnish actors were seeking to navigate two inter-imperial processes: maintaining autonomy while securing the best possible position within imperial structures. This is recounted and even glorified in Petrov’s account, but as a route to political independence. While independent nation-statehood solved this puzzle, it did so against the initial hopes of Finns and the prevalent imperial imagination. It blurred from sight the successes of the Grand Duchy in constructing national autonomy and democracy vis-à-vis both inter- and intra-imperial politics. In tune with the politics of the era, Finns saw their sources of societal autonomy and development as best secured within an imperial structure, and democratization and national development were means to gain such a position.

Finnish Independence and National Self-Determination

In 1917–1919, the major question for Finnish actors was how to secure the advantages achieved under empire, especially that of relative national self-determination in the face of a global order of large empires. In other words, what was the best way to navigate intra- and inter-imperial relations simultaneously?

“We are not opposed to Russia, that is, to a union of Finland with Russia, but we do not want to entrust our fate to anyone but ourselves,” stated Yrjö Sirola, a prominent Finnish Social Democrat at the time, in an interview for the New York Times, published on 14 July 1917.Footnote 5 Later, in 1918, the same newspaper described Svinhufvud, then serving as state regent, as a dictator seeking to “foist a [German] king on Finland.”Footnote 6 This displays the search by Finnish political actors for both imperial alliances and for self-determination. In this context it is easy to forget that the German Empire up until its defeat was a contender in promoting the rights of small nations, and that both socialist and bourgeois parties in Finland initially wanted to remain a part of Russia.

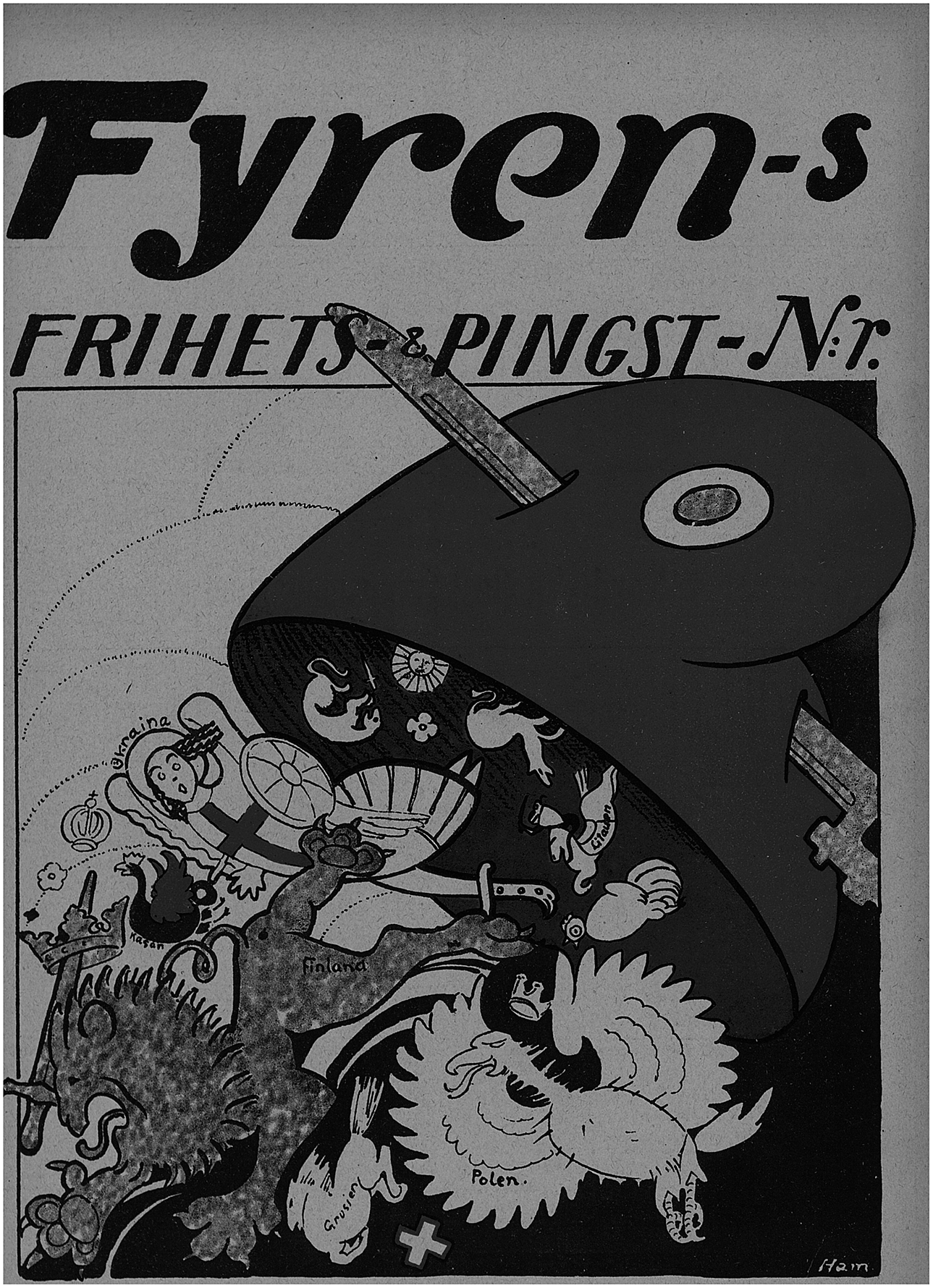

An example is image 1, published by a Finnish periodical in May 1917, during the Russian Revolution. It shows how the dismantling of the empire was perceived in the Finnish periphery. In the image we see the symbols of the different minority nationalities of the Russian Empire falling haphazardly, rather than emerging into a liberated independence. They plummet from the Phrygian cap that symbolizes freedom, which has been pierced by a bayonet, causing the imperial peripheries to tumble from their previous places into goodness knows what. The picture is ironically titled “Freedom’s Pentecost.”

Image 1. Minority nationalities of the Russian Empire are depicted falling chaotically from a Phrygian cap that has been pierced by a bayonet. Fyren-magazine, 25 May 1917. Source: National Archives of Finland.

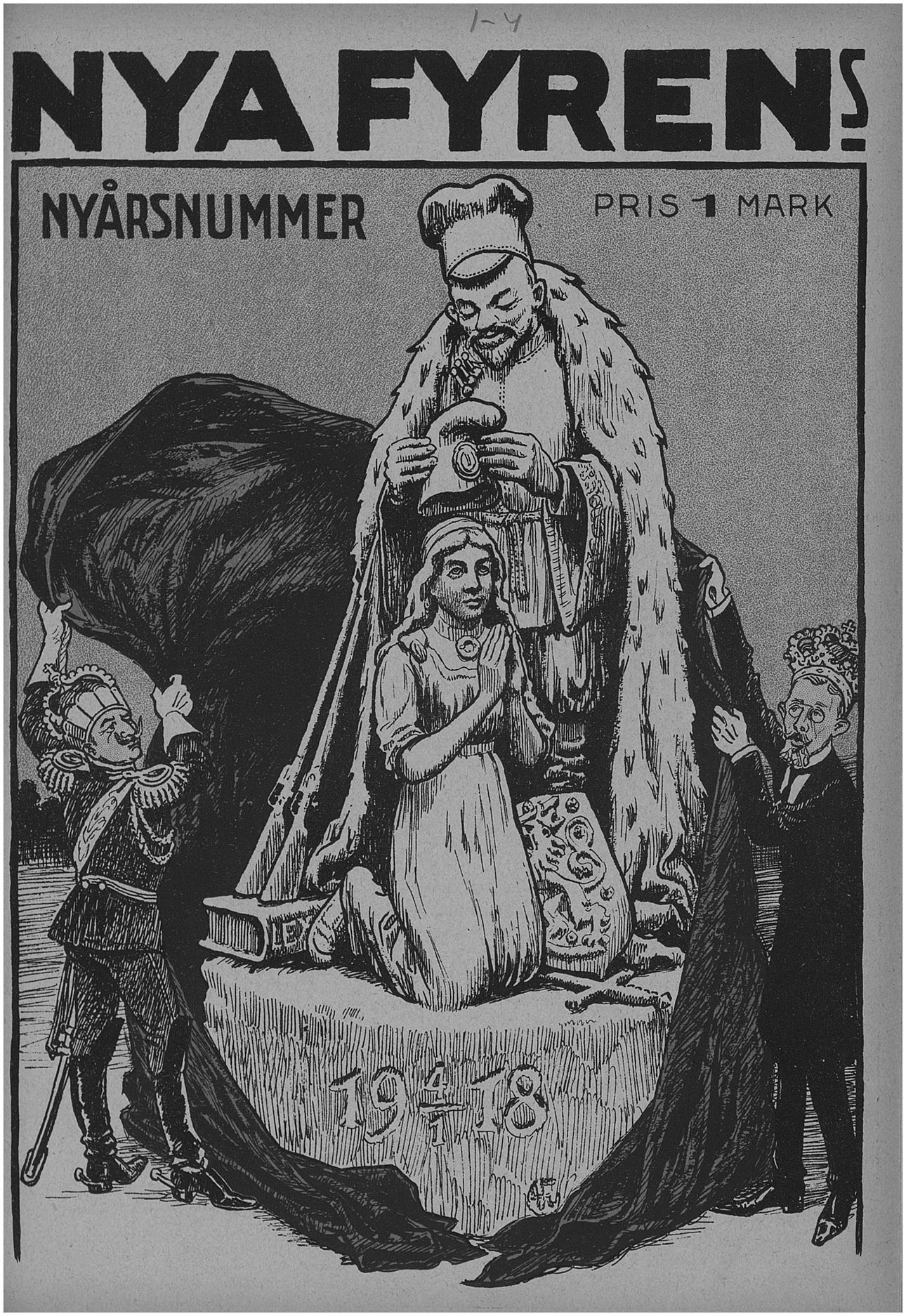

In image 2, the Phrygian cap of freedom returns in another cartoon from the same Finnish periodical. Here, the Finnish bourgeoisie and apparently the German Kaiser are shown unveiling a statue celebrating independence, in which a royally clad Lenin sets the cap of freedom onto the Finnish maiden praying at his knees. Unlike later methodologically nationalist historiography, this politically sharp depiction portrays both the intra- and inter-imperial politics characterizing the origins and making of Finnish national independence, and justifiably mocks its non-independent and non-national nature.

Image 2. A statue is ceremoniously revealed. It depicts a royally clad Lenin setting the Phrygian cap of freedom onto the maiden who represents the Finnish nation. This political satire cartoon imagines how Finnish independence will be remembered. Fyren-magazine, 1 Jan. 1918. Source: National Archives of Finland.

Neither was independence in the eventual nation-state form simply offered to Finland. It had to be made to fit in with the dominant inter-imperial policies of recognition. Despite the fact that in 1906 the Grand Duchy was the most democratic state in Europe, both Wilson and Winston Churchill considered the Finns civilizationally and racially too undeveloped for nationhood and self-determination. Wilson “regarded the Finns as deficient and compared their level of civilization to that of the Hottentots and the Iroquois,” and the British politician Lord Bryce suggested that “the Finns had become racially retarded through too long a contact with the ‘lower’ Slavic races” (Ruotsila Reference Ruotsila2005: 13–14). Wilson’s famous fourteen points specifically approved of only the separation of Poland from the Russian Empire and undertook to keep the empire otherwise territorially intact. Similarly, while Churchill’s 1919 plan to attack the Bolsheviks hinged on Finnish support, he nevertheless considered the idea of Finland remaining independent from a future non-Bolshevik Russia to be “preposterous and completely unrealistic” (ibid.: 33).

By the time The Country of White Lilies was published, this “deficient” Finnish race, then believed related to the Turks, had achieved both national development under empire and thereafter independent statehood, though Wilson at the Versailles Peace Conference refused to recognize Finnish independence. But, after attempts to restore a White Russia had failed, Finland began selling lumber products at exceptionally low prices, and with the help of private Finnish contacts with Herbert Hoover, who in turn influenced Wilson, Finns were able to leverage commerce and profit to change Western perceptions of Finland’s racial capacity for liberal democracy. The Inter-Allied Trade Committee took Finland under its control and Finnish national independence became a British and U.S. goal (Kuisma Reference Kuisma2010). Finland’s fate now rested not on definitions of sovereignty but, as Kuisma summarizes, “on Washington administrators, New York bankers, and the shifts in public American opinion” (ibid.: 196).

Within these shifts of sovereignty in the Finnish context, intra-imperial contestations and new definitions of inter-imperial world order were of utmost importance, ultimately trumping the projects of local Finnish actors. The case of the Grand Duchy of Finland’s search for sovereignty shows the great shifts that occurred in understanding and defining sovereignty, especially vis-à-vis democracy, statehood, and self-determination. Uncertainty and unboundedness marked this search for sovereignty’s articulation, but inter-imperial negotiation, continuity, improvisation, compromise, and national boundaries, concrete as well as definitional and symbolic, came to characterize its solution. Understanding this transition, as well as its later nationalist historiography as a continuous dynamic of inter- and intra-imperial relations, helps connect Finnish national development with the version of it fictionalized in The Country of White Lilies and the unorthodox spatio-temporal approach to national development that it signaled.

The Country of White Lilies in Post-Ottoman Space

Considering the Finnish historiography and the version of it presented in The Country of White Lilies, it is counterintuitive that the early Republican Turkish intelligentsia, as heirs to the Ottoman metropole, would celebrate a peripheral developmental model as particularly suitable for Turkish conditions. Despite this seeming incongruence, the book became an immediate success within the early Republican Turkish intelligentsia after a translation from Bulgarian to Turkish by the educator Ali Haydar (Taner) was published in 1928. “The copies of the first edition of the book ran out in months,” and in 1930 the Ministry of Education ordered re-prints from the State Publishing House and distributed them “as a gift to the about twelve thousand recipients of the ministry-issued Journal of Education” (Taner Reference Taner and Petrov1960: 5). New editions came out in 1940, 1942, 1944, 1946, 1952, 1955, and 1960, followed by many more different translations and editions after the 1960s. The book has remained important for Turkish political bibliography and images of development, surviving all the country’s turbulences and political developments. Most recently, in the 2020s, several editions have been published and sold out, and it is consistently a best seller of the main publication houses.

Why did this book, with its particular take on Finland’s national development, become so popular in Turkey and resonate with the intelligentsia of the early Republic? Narratives produced when the book was first published, and then republished in 1930, suggest that its reception was enmeshed with a fiction that Finnish and Turkish peoples shared a common ancestry and hence a sense of a common fate. Sometimes it was claimed that Finland and Turkey held similar positions vis-à-vis the Russian Empire and their “agrarian” industrialization problem. The networks of late Ottoman–early Republican Turkish educationists proved particularly receptive to the book and adopted it as a pragmatic developmental model for the “backward and lonely” Turkish nation. They rationalized this based on their equivalent positions regarding inter- and intra-imperial relations and the constructed common Finnish-Turkish ancestry.

The Turkish Republic was founded in 1923 as the inheritor of the Ottoman imperial state and metropole as well as the cultural traumas of ethnic cleansing and the Armenian Genocide of 1915 (Göçek Reference Göçek2014).Footnote 7 In the new Republic, non-Muslim minorities were labeled a security threat, sometimes even if they defined themselves as Turkish.Footnote 8 Thus, in early 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne sanctioned a population exchange between Greece and Turkey whereby some two million remaining Orthodox Christians from Turkey and Muslims from Greece were forcibly exchanged (Clark Reference Clark2009). The Turkish-speaking Orthodox Karamanlides were also deported from Turkey since they were deemed loyal to the Greek Patriarchate rather than Turkey due to their religious beliefs (Clogg Reference Clogg, Gondicas and Issawi1999). In the 1930s, with the consolidation of the Republic, state violence and forcible assimilation targeted non-Turkish Muslim populations, most notably in Turkish Kurdistan and Dersim (Üngör Reference Üngör2011). Within this conjuncture, during the early Republican era, an urgent question became “how to unify the ethnically, culturally and linguistically diversified Muslim population of post-Lausanne Turkey” (Ülker Reference Ülker2007: §2), without actually acknowledging the existence of diversity.

Acutely aware of the importance of race and whiteness in claiming developed “civilized” status in the postwar context, and facing the problem of national unity, the newly founded Turkish Republic prioritized scientifically proving that the Turkic race was not part of the yellow, but white (hence developed) races. “By the turn of the twentieth century, the Ottomans had well understood the significance of racial credentials for acquiring a meaningful existence in the new cosmology of modernity” (Ergin Reference Ergin2018: 832). Since the Republic’s beginning, then, defining the Turkish nation as “white” and deserving of a “Western” status has been central to the project of Turkish nationalism and the pursuit of inter-imperial recognition.

To achieve this end, state-sponsored anthropological work drew on eugenic theories prevalent in the interwar years and “anthropologists sought to prove that the Turks were not members of the Mongoloid race but rather belonged to the Caucasoid, Alpine race, the skull structure of which was brachycephalic” (Karaömerlioğlu and Yolun Reference Karaömerlioğlu and Yolun2020: 750). Perhaps the most famous example of this endeavor is the state-sponsored research of the Turkish President Mustafa Kemal’s adopted daughter, Afet İnan, for her dissertation. İnan measured sixty-four thousand “Turkish” skulls to determine the craniological type of the Turkish race, thus “proving” that Turks indeed belong to the white Caucasian race (ibid.).Footnote 9 Two defining moments of the creation of the Turkish Republic’s official stance on Turkish race and historiography were the state-sponsored Turkish Historical Congresses of 1932 and 1937. Underscoring the importance of the race question, Sadri Maksudi Bey, a member of the Turkish Historical Association, delivered this speech in the 1932 congress, “The question of race is one that highly concerns sociologists and historians. The necessity of us Turks to take a position on this matter need no explanation.… we put forward a new idea for Europe. We say that the race which has served the dissemination of civilization within humanity is the race that originated in Central Asia and were the forefathers of the Turks; and a signature feature of this race is being Brachycephalic” (Maksudi Reference Maksudi1932: 350).Footnote 10 “The race that originated in Central Asia,” according to the linguistic convention created by a mix of Finnish, Hungarian, and European linguists and archaeologists at the time,Footnote 11 included not only Turks and Central Asians, but importantly Finns and Magyars, as the Turanic races.Footnote 12 The idea of this relationship—culturally distant yet racially related—featured in imaginations of Finland from the late Ottoman period onward, which allows for comparisons across the inter-imperial positionality of the Finnish and Turkish nationalist actors.

As early as 1912, before the Great War and the publication of Petrov’s book, the Ottoman journalist and politician Celal Nuri (İleri) wrote in his travelogue: “The Finnish nation is from Turkish components … therefore Finns are our pure cousins…. This means that Turkish intelligence and labor has built and developed this faraway, forgotten land of the north. Truly, it is this race’s (life’s) work to leave its original motherland and conquer tens of thousands of kilometers away, to find potently enduring states and governments” (İleri Reference İleri2016: 40).

He also drew a positional equivalency with the Russian Empire: “In the South of Russia, we are its victims. In the North, Swedes and Finns are in our position” (ibid.). Celal Nuri argued that the Ottoman Empire had a lot to learn from these Scandinavian countries, but alas, information about them was scarce in the country. Indeed, the lack of general interest was evident when Finland became independent from Russia in 1917 and one of Istanbul’s major newspapers, Tercüman-ı Hakikat, gave it only one sentence: “The electoral reforms of the Finnish Diet have started today,” without further explanation (Tercüman-ı Hakikat, 3 Oct. 1917).Footnote 13 However, the publication of The Country of White Lilies aroused interest in the development of Finland, and important intellectual figures such as Turkish feminist Şükufe Nihal visited there after reading it (Nihal Reference Nihal1935). After the Great War and the Russian Revolution, Tatar refugees and migrants coming to the new Turkish Republic from Russia, especially educationalist figures such as Hamit Zübeyir, also contributed to the perception of Finland as a civilized cousin-nation.

This racialized argument was replicated in narratives around The Country of White Lilies. Right after its publication in 1928, another educationist, İsmail Habib (Sevük), wrote in an education periodical, “It is rare to find such useful books that would be preferred for New Turkey. For us, this book is a dynamic, lesson-giving, thought-provoking example. It is as if the author wrote this book thinking of New Turkey, so that Turkey can learn lessons from it, that new Turkey can find all the grief of its past and all the solutions of its future; if (other) nations read this book as a pamphlet, we should see it as a guide, and follow its path as if following a redeemer.” He continued:

This two-million Finn nation, this Finland squeezed between Sweden and Russia, conquered by one or the other, the country of mist and swamps, these Finns who are our relatives by blood and race because they come from Turan, how did they transform their country from a swampy hell to a heavenly land of white lilies?… The real value of the book lies not in that it teaches us Finland, but while teaching us Finland, it shows us what we are and what we will be. It is as if this two million Finnish people experienced this to ease the way for their bigger relatives, so that we can walk more surely, more securely the civilizational path we have chosen…. This is not just an example showing that we will prevail brilliantly, but also a proof of it” (Adana Mıntıkası Maarif Mecmuası, 15 May 1928: 15–16, our emphases).

Similarly, the Turkish teacher Mehmed Emin (Erişirgil) wrote in Hayat journal:

We need these kinds of works very much…. If I could, I would put this book in the hands of every passenger traveling between Haydarpaşa and Ankara, and while making them read this book, I would make them look at the villages around which are just a mass of dirt.… It shows us what kind of people could be created through working on the soul. One of the best sections of the book is the pages describing how barracks are people’s schools. These pages are for us a program from beginning to end.… These lines are from beginning to end a program” (Hayat: İlim, Felsefe ve Sanat Mecmuası, 26 Apr. 1928: 1, our emphases).

He continues, “Petrov wants to destroy the harmful thought of the country progressing through the creation of classes and making every class a tool for others’ exploitation; he wants to propagate the goal of creating a ‘community’ in which all individuals are strongly bonded to each other, the rural and the urban, the educated and uneducated components feeling the same feelings” (ibid.: 1).

In another issue of Hayat, the teacher Ziyaeddin Fahri (Fındıkoğlu) wrote, “Our renewal movement which has begun and progressed over a century has favored solely France, our philosophy and path only lightened up with the rays of sun coming from that window…. we need to turn to several corners of civilization…. The country youth who have on their shoulders the duty to make Anatolia similar to the country of white lilies can learn many lessons from this book, one of the qu’rans of the century” (ibid., 7 June 1928: 18–19, our emphasis). Another educator, Kemalettin Kaya, proposed a similar analogy: “This work shows how Suomis [Finns], a nation which has been smothered under Russian and Swedish governments, have worked to materialize their national culture. I think this book is worth not just reading, but at the same time memorizing, for the Turkish nation and Turkish youth who have materialized as a new and very energetic nation by ripping apart old bonds and wanting to reach the stage of maturity, since, because of the evil of the past, the nation has been lagging behind” (Hakimiyet-i Milliye, 6 June 1928: 4).

Ahmet İzzet similarly describes The Country of White Lilies as a crucial book endorsed by the Ministry of Education. After “repeatedly reading the book over and over within one week” with so much enthusiasm and awe, he also draws a geopolitical connection between Turkey and Finland, writing, “It is incumbent upon every Turk to read this story of liberation (kurtuluş) carefully. Because we, like our racial brother the Finnish nation, are being reborn. Even if not to the same extent, we also were suffering under the domination of foreign elements and unconscionable governments. The story of the Finnish nation is more or less the story of the Turkish nation” (Hür Fikir, 2 July 1928: 2).

Again in 1928, the mayor of Aksaray, a province in Central Anatolia, wrote in Aksaray Vilayet Gazetesi (the Aksaray Province Gazette): “Swampland and valley of death, home of poverty and misery, known as Finland, in the far north of the globe, with long winters, infertile land and barren country, with the efforts and enlightening of village cooperatives, village teachers, and voluntary doctors, how today it became the country of happiness and beauty, how the smallest solidarity and sign of people’s power multiplied” (Aksaray Vilayet Gazetesi, 21 June 1928, quoted in Taner Reference Taner1998). Note here that the Finnish welfare state was not constructed until the 1960s, and in the interwar years Finland was much poorer than its Eastern and Central European newly independent peer nations (Koponen and Saaritsa Reference Koponen and Saaritsa2019).

In the “Journal of Education” published in the province of Adana (Adana Mıntıkası Maarif Mecmuası), the author Baki TonguçFootnote 14 pointed out that the new Minister of Education, Mustafa Necati, was taking on an unprecedented inspection tour in the country, which signaled state-sponsored educational development for the future. He compared Necati to previous ministers, who did not take such trips, and would not even be able to find the locations Necati visited on a map. Tonguç furthermore likened Necati to Snellman in Petrov’s book, and hoped that this educational movement was a signal that “it is the beginning of the establishment of Snellman’s teacher army in our country" (Adana Mıntıkası Maarif Mecmuası, 31 July 1928: 9). It is significant that this article was written in July 1928, just a few months after the publication of The Country of White Lilies. This suggests that the political imagery and characters in the books had already become a reference point for educationists.

The early Republican success of the book proceeded hand in hand with the projection of Turkish issues onto the Finnish experience. For instance, in her 1935 memoirs of Finland, Şükufe Nihal established a narrative of the Finnish women’s movement having succeeded in winning the franchise, while projecting onto this movement the issues facing the Turkish women’s movement, such as low levels of education (Nihal Reference Nihal1935). A 19 August 1936 article in the Cumhuriyet states that the success of Finns in international wrestling comes from their blood, and so Turks can be naturally successful too if they simply train properly.

This model of development and the sense that the two peoples shared similar fates was also apparent in the much-celebrated program of Turkish Village Institutes. Their approach was to educate peasant children on rural issues and send them back to their villages to teach the other villagers, thereby accelerating the economic and cultural development of the agrarian society. These Institutes can be compared to Finnish village schools that the educator Hamit Zübeyir (Koşar) wrote about in the periodical “Turkish Homeland” in the late 1920s (Türk Yurdu, Dec. 1929: 29–33).Footnote 15 The Country of White Lilies was a staple book in these Institutes, which cultivated an image of newly graduated teachers going off to enlighten distant Anatolian villages with the book in hand. A graduate from one of the Village Institutes, Ali Dündar, shared his memory of lying in its infirmary in 1942 reading The Country of White Lilies. He was visited by the President of Turkey, İsmet İnönü. İnönü, staging an inspection, told Ali that they had read the book in the military in his youth, and discussed it within the context of the fall of empires and rise of nations (Cumhuriyet, 2 Feb. 1999).

The Village Institutes project did not last long and was abolished in the late 1940s, and “the white lilies … ripped from their roots” (Cumhuriyet, 1 June 1962). Yet Petrov’s book retained its popularity, and as late as 1963 a village development community in Thrace announced that they would gift a cow worth 2000 liras to the farmer who read and summarized it best (Cumhuriyet, 5 Aug. 1963).

The book’s importance for the Turkish nationalist political imagination can also be gauged from interviews conducted after the officer’s coup in 1960, with its leaders. The book’s title came up consistently as the most influential book for the coup cadres. For instance, when a Cumhuriyet reporter asked Major Çelebi, “Did you have dreams and desires as a student?” he answered, “Of course, my biggest desire, you can if you wish call this a dream, was to make a reality in our country the system of life and community seen in the famous book The Country of White Lilies, which I had read as a student and been affected by” (Cumhuriyet, 1 Aug. 1960). Similarly, Major Ersü remarked, “I love the Country of White Lilies and its world,” and stressed that the education of the people (peasants) was the most important issue facing Turkey (Cumhuriyet, 25 July 1960). When asked about influences on him as a student, Captain Solmazer also pointed to the book (Cumhuriyet, 22 July 1960).

However, hopes of fast village development through this model were dashed and the experiences of village teachers contradicted their theoretical expectations. In several narratives we find the book also became a symbol of alienation. For instance, in a 1943 novel, writer Kemal Bilbaşar portrayed a disenchanted village teacher who thinks to himself: “What about my programs? My poor programs! The Country of White Lilies would have envied my town! And this ascendance would have been my doing” (Cumhuriyet, 4 Jan. 2005). Instead, he faced the realities, poverty, and the exploitative governance of village life and his dreams were shattered. Similarly, in 1983, Hürrem Arman wrote of her generation, who went to villages carrying Petrov’s book only to discover that they knew nothing of village life (Cumhuriyet, 1 Oct. 1983). Turkish intellectuals Şevket Süreyya Aydemir (Aydemir Reference Aydemir1968: 486) and Nadir Nadi (Cumhuriyet, 23 Oct. 1980) criticize the 1960 coup leaders for reading only this book and knowing little about realities on the ground. In the hands of novelists and intellectuals critical of the Turkish nationalist project, the book can symbolize a depoliticized and idealized version of national development associated with state ideologies, in stark contrast to the reality of political violence carried out against non-Turkish minorities in the process of nation-building (e.g., Adalet Ağaoğlu’s Reference Ağaoğlu1973 Ölmeye Yatmak).

Despite these criticisms, the developmental model depicted in the book continues to resonate in the Turkish political imagination, and new editions are still being sold. Networks of Turkish migrants, refugees, and educationalists who traversed the inter-imperial intellectual and physical space, some of whom spoke multiple languages, made The Country of White Lilies an important part of the Turkish political canon. They did so while constructing narratives of Turkish-Finnish shared ancestry, and common positionalities as new agrarian nations, oppressed by empires, seeking fast developmental routes to “catch up” with the Western civilization on their own terms. We argue that the book supported three ideological purposes. First, it allowed the early Republic intelligentsia to distance themselves from the Ottoman past, casting the Ottoman Empire as a dark age and the Turkish Republic as a “brand new world of light” (Halil Nimetullah Reference Nimetullah1932), while rejecting “foreign traditions” (ibid.) of development. Second, we suggest that the book’s model might have offered a way out of the racialized civilizational models imposed by the Western empires, in which “uncivilized” nations needed external powers to “civilize” them.

Interestingly, while Turks were enthusiastic about the colonial success story of the Finns—their “little cousins” as the racial theories of the time suggested, since that served as proof that the Turks, too, would prevail as a modern civilization—the Western powers initially refused to incorporate Finns into the new family of self-determined nations, at the Paris Peace Conference. The Finns, described as uncivilized by Woodrow Wilson, achieved cultural and civilizational heights seemingly purely by internal cultural developments and national solidarity. That could have resonated with the Turkish intelligentsia facing war-torn Anatolia, whose racialized definition vis-a-vis Europe had been uncertain and shifting through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Finland became a successful model in multiple ways, achieving racialized, civilizational, and political recognition from Western nations, yet from a position outside of Western empires, even while dominated and threatened by the non-Western Russian imperial state. All these aspects could appeal to those constructing a Turkish nation as a victim of the Ottoman imperial state.

We also suggest that the book served a third ideological purpose, not through what it offers, but through its silences, particularly regarding ethnic violence and democratic processes. First, the book assumes a homogeneous nation devoid of political violence. This might have been a welcome erasure of social conflict for the Turkish intelligentsia and the state in the aftermath of the 1915 Armenian Genocide, ethnic cleansing of non-Muslims between 1915–1934, and mass violence against Kurds in the 1920s and 1930s. Silencing and repressing demands for reparations and reconstruction, this developmental model instead stressed solidarity between co-nationals and the importance of educators as key to development.

Second, the corporatist and intellectual-driven developmental paradigm, coupled with the silences around any political or democratic process in Finland’s national development, present a depoliticized route for development. Hence, the book proposes an approach to development that differs from both liberal and class-based ones, which the elite of the Turkish nationalist project saw as divisive and dangerous. After a brief and controlled experiment with a multi-party system, Turkey in the 1920s and 1930s was characterized by an authoritarian single-party regime under the dictatorship of Mustafa Kemal, as “the free press was suppressed, [and] parliamentary liberalism was rebuked as a dead and anachronistic ideology. There was no room for parties, parliamentarianism, or liberalism” (Gürpınar Reference Gürpınar2013: 199). We suggest that the anti-individualist, corporatist model of development presented by The Country of White Lilies, with self-sacrifice and collective will as its foundation stones, would have been quite amenable to the Kemalist intelligentsia. With the firm establishment of an authoritarian one-party regime in the 1930s under the Kemalist regime, the glaring absence of democratic processes in the developmental model offered by Petrov’s Finland could have led to its elevation as a non-political model of development.

The Country of White Lilies after Political Independence

In 1926, the Finnish right-wing paper Aamulehti published a commentary on reforms in post-Ottoman Turkey which criticized the Turks for relinquishing their imperial position in an effort to become “an insignificant Balkan state … the rentee of a rentee in the backyard of Europe” (“Loistonsa menettänyt puolikuu,” 24 Jan. 1926: 9). To understand this commentary, one must know that the same newspaper had been forced to relinquish its hope of importing a German king for Finland and had only bitterly accepted Finland becoming an independent nation-state with no imperial protection. The idea of a nation with a legitimate claim on imperial power, on inter-imperial sovereignty, embarking on a project of nation-state independence, must have seemed to represent the ills of the era. In this sense, The Country of White Lilies connects an imperial periphery doing its best to resist national independence with an imperial metropole adopting that same periphery as a successful model of national development, in an effort to dismiss its imperiality in favor of nation-statehood.

This gives pause for how we should approach nation-state independence and its relation to imperialism. If imperial rule and domination were vulnerable to democratization and nationalization, then national self-determination helped reconcile these issues by confining democracy to the national state, in effect gerrymandering the world into individual units that, within themselves, might have been democratic and have sought national autonomy, but could no longer connect that with inter-imperial struggles. In contrast, before the Great War, “…most national movements striving for emancipation attempted to strike deals with the empire” and “even if a national movement stood in clear opposition to a specific kind of imperial rule and its actual national policy, the emperor and the dynasty, the military or the imperial high culture could still serve as objects of identification” (Ther Reference Ther, Berger and Miller2015: 578).

The Country of White Lilies spoke to intra-imperial dynamics and politics of the Russian imperial space in this changing constellation. A liberal socialist priest, Petrov wrote against the imperial state’s intervention in national development and the connection of the state and the church. He detached the nation from the civilizational logic of the empire or the sovereignty of a body politic. In this, Petrov circumscribed both Wilsonian and Leninist forms of development that married the state, the nation, and self-determination. Indeed, before 1918, and in the idealized world of The Country of White Lilies, politics and resistance within empire, specifically in national frameworks, were not geared for or against empire. In this context, it would be false to speak of nation-building in the sense that the finished product, a self-determined nation, would then be something emancipated from empire with its sovereignty detached from intra- and inter-imperial relations. Here Petrov’s vision departs from, for example, Benedict Anderson’s contextualization of the nation as politically vying for the state and growing out of empire (Reference Anderson2006).

As represented by image 1, the end of empire was not a release into freedom, but the end of one conception of, or search for, freedom. The Grand Duchy vanished, and as Finland fell into the unknown with the other minority nationalities, as the Finnish periodical depicted the situation, it had to desperately grasp onto something. These were political problems to which political solutions were sought and found, not natural developments of social and national relations. Elsewhere, the Turkish Republic was struggling to define its place as the newly independent core of the former Ottoman Empire and found unexpected resonance between its aims and the model laid out in The Country of White Lilies.

Inter-Imperiality in Post-Imperial Space

The sociology of empires and nationalism have remained curiously isolated from each other, as well as from discussions of historiography, even though recent scholarship on nationalism and state-formation suggests a close connection between imperial politics and national formations (e.g., Mazower Reference Mazower2009) and stresses the importance of situating “states in international and global dynamics” (Orloff and Morgan Reference Orloff, Morgan, Morgan and Orloff2017: 15). Mainstream nation- and state-making literatures have not adequately dealt with imperial legacies but have instead tended to focus on sovereign structures as units of analysis, leading to the pitfalls of methodological nationalism and a conflation between “nation” and “state” (e.g., Tilly Reference Tilly1992; Hechter Reference Hechter2001; see Bhambra Reference Bhambra2016; and Boatcă and Roth Reference Boatcă and Roth2016, for critiques). However, as Etienne Balibar (Reference Balibar, Wallerstein and Balibar1992) reminds us, the decolonization processes and creation of new political spaces after the two world wars, and the construction of “equivalences” between all nation-states, did not signify an abolition of imperial logics—it led to their continuation in different forms.

Eurocentric historiographies that explicitly or implicitly assume the primacy and superiority of Western models of nation-building and development have been replicated in methodologically nationalist work, resulting in a superficial depiction of governance models diffused from the West to the rest of the world (Go Reference Go2012; Reference Go2014). Under this paradigm, sovereign structures and non-Western empires that cannot economically or militarily compete with the developing West have been understood to embark on “defensive modernization” and nationalization, and concepts like “Westernization” and “traditionalism,” the “East” and the “West,” “freedom” and “dependency” have been employed as binary opposites, obstructing alternative visions by assuming the explanatory value of these ambiguous terms (Go Reference Go2012; Reference Go2016; Bhambra Reference Bhambra2016). These concepts far too often replace empirical research as “explanations” rather than being understood as elements within a discursive context to be explained (Latour Reference Latour2005). Moreover, methodological nationalist work has obscured global topographies of power distribution, treating all nation-states as comparable equivalent units, and in effect creating an artificial and uniform “isolated” domestic sphere across states that are in very different structural positions within the world order (Balibar Reference Balibar, Wallerstein and Balibar1992).

Eurocentric historiographies that have privileged Western metropoles as primary units of analysis and paradigmatic “model cases” (Krause Reference Krause2021) of nation-building have been successfully challenged by postcolonial critiques in debates within the sociology of empires. Post-colonial theory has successfully challenged the universality and ontological primacy of Western categories of history-writing with its particular understandings of development, empire, and nation-making (Guha Reference Guha1998; Chakrabarty Reference Chakrabarty2008; Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee1993) and have highlighted dynamism and politics in the peripheries of colonial empires as constitutive of metropolitan imperial politics (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007; Makdisi Reference Makdisi2000; Hussin Reference Hussin, Morgan and Orloff2017). However, most postcolonial comparative analyses have remained within the spatial limits of Western imperial formations. Comparative studies for the most part remain dominated by comparisons across imperial politics and peripheries of Western empires (Go Reference Go2013; Jung Reference Jung2015), intra-imperial periphery-metropole connections (Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2008; Wilson Reference Wilson2015), and national development in the postcolonies of Western Empires (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee1993; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2001). Land-based non-Western empires that have “lost” after the World War I, such as the Russian and Ottoman Empires, have remained in the margins of the sociological and postcolonial field; sociological studies on empires after the “imperial turn” have tended to focus on “the European colonizer and the non-European colonized” (Göçek Reference Göçek and Go2013: 39). Consequently, the contemporary sociology of empires has been dominated by studies of Atlantic and Continental colonial empires (e.g., Hardt and Negri Reference Hardt and Negri2001; Go Reference Go2013; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007).

Göçek points out that sociologists of empires need to expand their conceptual tools and empirical sophistication by generating theories and concepts that also address the experiences and global significance of non-Western empires. She writes, “One needs to analyse such ‘marginalized’ cases in order to recover the nature of their resistance to or negotiation with the West on the one side, and the dynamics of the local processes independent of the West on the other” (2013: 77). These marginalized cases have the potential to provide alternate sites of knowledge that can challenge epistemic inequality and the hegemony of the West in postwar accounts. Drawing from Walter Mignolo and Madina Tlostanova, Göçek writes of the in-betweenness of Ottoman and Russian Empires vis-à-vis Western Empires and their colonies, making it “ontologically and epistemologically difficult to conceptualize them within the dominant Western hegemonic discourse” (ibid.: 83).

Despite this critique, “we continue to make the oddly Eurocentric assumption that western European imperialism accounts for all recent imperialism, with the concomitant misperception that all territory is either a European (post)colony or uncolonized” (Doyle Reference Doyle2014: 162). This approach fails to account for non-Western imperial formations and their production of imperial difference, as well as to address the anti-imperialism and inter-imperial imaginations of the new Turkish Republican intelligentsia. These regions cannot be separated from colonial modernity, while also being embedded in regional inter-imperial logics. As Jovanovic points out, “even as the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires existed within a context of coloniality, they did so with their own specificities, irreducible to the theoretical matrix emerging out of the Atlantic and Indian oceans.” (Jovanović Reference Jovanović2022: 247–48). The Ottoman Empire faced “diffuse and informal colonial politics” (Philliou Reference Philliou2016: 457) from a range of imperial powers including Russia, Italy, and Austria-Hungary as well as Britain and France within its territories especially in the second half of the nineteenth century, while also maneuvering violently to establish imperial control within its claimed territories.

An inter-imperial approach is particularly fruitful in untangling neglected connections in regions that do not fit into the “privileged research objects” of different theoretical paradigms, including postcolonial theory. Krause (Reference Krause2021) argues that sociologists pre-reflexively privilege some contexts over others in research, creating inequalities in how we approach the world, and producing theoretical abstractions. She terms the privileged and overstudied material research objects as “model cases.” Thus, for Krause, beyond a sociological canon of authors, there also exists a sociological canon of privileged research sites and objects (ibid.: 2). In addition to being studied continuously, these cases, like the French Revolution, become templates for understanding a generalized and abstracted concept, like revolution itself. These privileged objects are “assumed by collective convention to have the capacity to produce insights of general relevance” (ibid.: 102). Postcolonial theory itself is not immune from privileging certain places within its own theoretical lineage, particularly theorizing from South Asia and the British Empire. Both the Western European “model cases” of national development and the postcolonial “model cases” privileging the Anglo-Saxon postcolonies fall short of explaining the immediate popularity of The Country of White Lilies, and the celebration of a Russian imperial periphery in Turkish political imagination. In our analysis of the book’s enduring popularity in the Turkish republican imaginary, we have built on the bourgeoning work of Doyle’s theoretical model of inter-imperiality, and Göçek’s and Krause’s calls to produce sociological knowledge that does not simply reproduce the “model cases” of major theoretical paradigms.

Doyle (Reference Doyle2014) argues that scholars of empire can build upon the insights of postcolonial approaches while also bringing inter-imperial fields of action into focus by adopting an “inter-imperial model” and centering the “inter-imperial positionality” of actors. She develops the theoretical framework of “inter-imperiality,” defined as “a political and historical set of conditions created by the violent histories of plural interacting empires and by interacting persons moving between and against empires” (ibid.: 160). Approaching the Transylvanian region in the early twentieth century as an inter-imperial zone, Parvulescu and Boatcă (Reference Parvulescu and Boatcă2022) contend that, through Doyle’s framework, “Anti-imperial themes and structures become legible in relation not to one empire but to multiple conflicting empires vying for control in the region,” allowing the authors to highlight the unequal degrees of inter-imperial agency seen through “the prism of a negotiation across empires” (ibid.: 8). They therefore position the self-conceptualization of subjects as well as socio-economic organization in a Transylvanian village within inter-imperial legacies and negotiations. A second analytical move the authors make is resisting “the reification inherent in the assumption that empires interact with each other only as state formations by revealing connections, exchanges, and mobilizations across empires as well as below the state level” (ibid.: 10). Thus, we can conceptualize the cultural field in inter-imperial zones as being permeated by “inter-imperial semiotics and conditions of production” (Doyle Reference Doyle2014: 189), shaped particularly through processes of migration, inter-imperial positionality, and the socio-political conjuncture. Drawing on these insights, we have approached The Country of White Lilies as an inter-imperial object, analyzing not the immediate contents of the book, but rather the relations and meanings Turkish intellectuals constructed around it within the inter-imperial context of the post-imperial space.

Drawing from these literatures and trying to avoid some of the epistemological pitfalls we have identified, we suggest an approach that focuses on the movement of The Country of White Lilies across imperial and post-imperial spaces to further our understanding of the global politics of the postwar era. Following Göçek’s call for generating social theory from non-Western imperial spaces, we have focused on The Country of White Lilies as a red thread and a hermeneutically dynamic object, tracing how it moved across imperial and post-imperial spaces and how it was appropriated and attributed meaning by different imperial and national actors in a post-World War I context. Through this approach, we have highlighted connections to imperial and global politics at two levels. First, we argue that while the Turkish national project reimagined Turkey as a nation that had been colonized by its own empire, Finnish political actors at the time of independence had associated Finland’s self-determination with dependency rather than independence. This allows us to ask: what does the reception and popularity of the book in post-Ottoman Turkey, which was a quite different political context than Finland, tell us about postwar global politics? Second, we suggest that this odd pair with a curious connection helps us, to paraphrase Göçek, generate knowledge of the fall of empires and the postcolonialities that follow them from a perspective not influenced by the Western European historical experience and provide, in political, spatial, and temporal terms, an inter-imperial perspective on early twentieth-century national development projects.

Toward a New Spatio-Temporal Approach to Politics of Empire

As concluding remarks, we want to suggest several points that seek to move us toward a new spatio-temporal approach to the politics of empire. First, the movement and political entanglements of Petrov’s book, considered together with the imperial and global entanglements of the Finnish political actors seeking imperial protection and Turkish actors seeking to reject empire, alert us to the pitfalls of conceiving of global politics within separate spheres of the East, the West, and the in-between. Rather, we need to think of imperial politics in an integrated and relational perspective, where the interactions between inter-imperial spaces do not become anomalies that slip through conceptual categories, but instead are important units of analysis that inform global politics. This will also help us avoid the ossification of relationally created categories into taken-for-granted conceptual tools; in which case the relational dynamism behind the categories disappears from the sight of the researcher and becomes a particular spatial displacement of past imperial historical understandings onto the present. Through adopting Doyle’s concept of inter-imperiality and sensitivity to layers of (inter)imperial legacies, we also highlight the importance of the silence of imperial legacy in the case of the reception of The Country of White Lilies. While the book refrains from addressing fresh cultural traumas of ethnic conflict, genocide, war, and migration, it acquires an apolitical dimension that makes it particularly non-controversial.

Secondly, the movement of the book forces us to rethink the epistemic and temporal rupture experienced by both Russia and Turkey, and their post-imperial spaces, in the 1920s. If the Turkish nationalist actors had not given up on the imperial project, the book would not have made sense because there would be no national historical object imaginable outside decolonization, or emancipation. The lamentation of the Finnish rightwing newspaper about Turkey’s wasted imperial position speaks to the conditions within which the book became mobilized. While the Finns projected there their own lost imperiality, the Turkish actors embraced the alternative story of national development on their own terms, outside of and not brought about by the inherent imperiality of the caliphate. Thus, the first president of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, fashioned the caliphate and the sultan as the other of himself, before he could become Ataturk, the father of the Turkish nation (Adak Reference Adak2003). These narratives coalesced in the event of national independence after the Great War, but temporally in reverse; the past of the Finns allowed the Turks to project into the future a past of national development that was confirmed by Finnish independence, whereas for the Finns the future jeopardized this same past. The temporal tension between the past and the future was the opposite for the Turkish and Finnish nations, and only connected within the nation-state independence of the present. The Turkish national project sought to retrieve from the past an imagined community for the future, whereas the Finns had to rewrite a nationalist historiography that escaped the Petrovian version of the past: national development under imperial rule. A focus on the inter-imperial positionality of both Finnish and Turkish actors, and the contemporary inter-imperial politics of development and racialization at the time, allows us to make sense of these displacements.

Lastly, by highlighting this neglected case of knowledge transfer and inter-imperial linkages between non-Western empires, we join the project of decentering the “model cases” (Krause Reference Krause2021) of national development and contribute to theorizing from the experiences and global imaginations of actors within the post-imperial spaces of non-Western empires (Göçek Reference Göçek and Go2013). We show that rather than existing as modular forms to be transported, and originating from the West, categories of “nation,” “development,” “freedom,” and so forth acquire their significance from their inter-imperial contexts of meaning, as well as the coloniality of modernity, for actors imagining their own global position. In so doing, we suggest a move toward a spatio-temporal approach to politics of empire that takes into account spatial and temporal displacements in giving meaning to and acting upon inter-imperial politics of empire.

We suggest that The Country of White Lilies works as a medium for historical time beyond past categories of imperiality and civilization of both the Ottoman past and that past’s others. The Turkish object becomes the national subject without having to be emancipated in reference to those pasts. Moreover, the connections to the Finnish relatives and their struggles, understood and defined in imperial, racialized, and oppressed terms, gives agency to the imagery of a colonized Ottoman subject. The imperially colonized and peripheral Finn becomes the Turkish future. This not only brings a peripheral and imperial development model alive in a national history, but it also reverses the work that national independence does vis-à-vis the imperial past, reformulating an old dependency after a discontinuity that supposedly had transcended it. In a nutshell, within almost unescapable inter-imperial and developmentalist structures, the national historical time becomes not the guarantor of a (glorious) future, but a provider of an imaginable past and possibly a starting point, stealing from nation-state independence its role.