Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 June 2009

Strikes became legal in France more than a century ago. Since their first partial legalization in 1864, the right to strike has waxed and waned, the great federations of labor have sprung from conflicts within France's modern industries and bureaucracies, and the proportion of strikes leading to shootings, beatings, sabotage or imprisonment has diminished. The strike has appeared to modernize, to take on new sophistication as a means of regulating conflict, to go from savage to civilized.

1 Journal mural, mai 1968 (‘Les murs ont la parole]), Besançon, Jlien, ed. (Paris: Tchou, 1968), p. 59.Google Scholar

2 Marx, Karl, The Poverty of Philosophy (New York: International Publishers, 1963), p. 173.Google Scholar

3 Wildcat Strike: A Study in Worker-Management Relationships (Yellow Springs, Ohio: Antioch Press, 1954)Google Scholar. For a cross-section of this approach see the essays in Industrial Conflict, Kornhauser, Arthur et al. , eds. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1954), pp. 59–185.Google Scholar

4 For a critique of the human relations approach see Goldthorpe, John H. et al. , The Affluent Worker: Industrial Attitudes and Behaviour (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), pp. 177–8.Google Scholar

5 Goetz-Girey, Robert, Le mouvement des grèves en France, 1919–1962 (Paris: Editions Sirey, 1965)Google Scholar; Andréani, Edgard, ‘Les grèves et les fluctuations de l'activité économique de 1890Google Scholar à 1914 en France’, thèse pour le doctorat de Sciences économiques, 1965 (cited in Michelle Perrot, ‘Grèves, grévistes et conjoncture. Vieux probleme, travaux neufs’, Le mouvement social, No. 63 [April-June 1968], p. 109)Google Scholar; March, Lucien, ‘Mouvements du commerce et du crédit, mouvement ouvrier …’, Bulletin de la Statistique Généale, 1 (1912), 188–222Google Scholar; Rist, Charles, ‘Relations entre les variations annuelles du chộmage, des grèves et des prix’, Revue d'Economie Politique, 26 (1912), 748–58Google Scholar; Simiand, Francois, Le Salaire, Vol. 2Google Scholar: L'Evolution sociale et la monnaie (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1932), see especially pp. 200–10.Google Scholar

6 Knowles, K. G. J. C., Strikes: A Study in Industrial Conflict (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1952)Google Scholar; Griffin, John I., Strikes: A Study in Quantitative Economics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939)Google Scholar; Rees, Albert, ‘Industrial Conflict and Business Fluctuations’, in Kornhauser, Industrial Conflict, pp. 213–2–Google Scholar; Levitt, Theodore, ‘Prosperity versus Strikes’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 6 (1952–1952), 220–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Andrew R. Weintraub, ‘Prosperity versus Stikes: An Empirical Approach’, ibid., pp. 231–8. For a critique of this approach to French labor history see: Bouvier, Jean, ‘Mouvement ouvrier et conjonctures économiques’, Le mouvement social, No. 48 (July-September 1964), pp. 3–28Google Scholar; Lequin, Yves, ‘Sources et méthodes de l'histoire des grèves dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle: l'exemple de l'lsère’, Cahiers d'Histoire, 12 (1967), 215–31.Google Scholar

7 Serge Mallet, , La nouvelle classe ouvrière (Paris: Seuil, 1963)Google Scholar; Belleville, Pierre, Une nouvelle classe ouvrière (Paris: Julliard, 1963)Google Scholar; see also Hamilton, Richard, Affluence and the French Worker in the Fourth Republic (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; for a similar approach to conflict in the United States see Leggett, John C., Class, Race, and Labor: Working-Class Consciousness in Detroit (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968).Google Scholar

8 Kerr, Clark and Siegel, Abraham, ‘The Interindustry Propensity to Strike: An International Comparison’, in Kornhauser, Industrial Conflict, pp. 189–212Google Scholar; Ross, Arthur M. and Hartman, Paul T., Changing Patterns of Industrial Conflict (New York: Wiley, 1960)Google Scholar; Rimlinger, Gaston V., ‘International Differences in the Strike Propensity of Coal Miners: Experience in Four Countries’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 12 (1959), 389–405CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Rimlinger, , ‘The Legitimation of Protest: A Comparative Study in Labor History’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 2 (1960), 329–43CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Kerr, Clark et al. , Industrialism and Industrial Man (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960)Google Scholar; Warner, W. Lloyd et al. , Yankee City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963Google Scholar; one-volume abridged edition), especially pp. 270–354; Pope, Liston, Millhands and Preachers: A Study of Gastonia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967Google Scholar; paperbound edition), especially pp. 205–330. Duveau, Georges, La vie ouvrière en France sous le Second Empire (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1946).Google Scholar

9 Ross, and Hartman, , op. tit., pp. 115–40, 172–81Google Scholar. J. E. T. Eldridge has recently criticized Ross and Hartman on other points, questioning their assertion that industry-wide bargaining and labor governments reduce labor disputes. See his Industrial Disputes: Essays in the Sociology of Industrial Relations (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968), pp. 23–35.Google Scholar

10 ‘Incidence and Duration of Industrial Disputes’, International Labour Review, 77 (1958), 456.Google Scholar

11 Aguet, Jean-Pierre, Les grèves sous la Monarchie de Juillet (1830–1847) (Geneva: Droz, 1954)Google Scholar; France: Ministère du Commerce. Office du Travail, Les associations professionnelles ouvrirès, 4 vols. (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1894–1904)Google Scholar; France: Statistique Générate de la France. Ministere du Commerce. Statistique annuelle, years 1885–9 (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1888–1890). Mme Michelle Perrot, of the Institut d'Histoire Economique et Sociale, is about to publish a magisterial examination of industrial conflict in France from 1871 to 1890, including a detailed examination of the Statistique annuelle.Google Scholar

12 France: Ministère du Commerce. Office du Travail, , Statistique des grèves e des recours a la conciliation et à I'arbitrage, 1892–1935 (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1892–1939)Google Scholar; France: Ministère du Travail, , Bulletin, 1936–1938.Google Scholar

13 France: Ministère des Affaires sociales, Revue française du Travail (RFT). RFT data include strikes of workers in nationalized industries but not of civil servants (Fonction publique); see on this Sinay, Hélène, La grève (Paris: Dalloz, 1966), p. 76.Google Scholar

14 The calculation of strike rates by period and industry requires data on composition of the labor force by period and industry. We have placed in the machine record the relevant labor force data from the censuses of 1886, 1891, 1896, 1901, 1911, 1921, 1926 and 1931, interpolating in order to derive figures for intercensal years. In general we have made the adjustments and aggregations necessary to produce standardized labor force denominators comparable to the categories the Statistique des grèves used in reporting the strike numerators. For the censuses see France: Statistique Génèrale de la France, Résultats statistiques du dénombrement de … (1886, 1891, 1896)Google Scholar; Résultats statistiques du recensement généal de la population effectué le … (1901, 1906, 1911, 1921, 1926, 1931).Google Scholar

15 Goetz-Girey, , op. cit., pp. 72–92, presents excellent year-by-year data on the duration, size and frequency of strikes for France as a whole between 1919 and 1962. Those and other pages of his monograph contain abundant and important information on French strike activity not presented in this article or anywhere else. The present analysis differs from Goetz-Girey's in emphasizing and graphing the shape of the strike, in dealing with a longer period of time, in expressing the frequency of strikes as a function of the industrial labor force, and in providing detailed information on industrial variations in duration, size and frequency.Google Scholar

16 T. J. Markovitch identifies the years around 1930 as the end of a century-long secular movement of economic growth. The Great Depression marked the beginning of a twenty-five year period of stagnation, one which France began to recover from only in the late 1950s. We argue that the ‘modern’ pattern of strikes begins with this stagnant period. Whether economic decline itself generated the distinctive modern shape (as a poor conjoncture may compel short, symbolic strikes), or whether other variables such as a growing politicization of the labor movement are strategic remains open to question. L'industrie française de 1789 à 1964: Conclusions générales (Marczewski, J., ed., Histoire quantitative de l'économie française, Vol. III)Google Scholar, in Cahiers de l'lnstitut de Science Economique Appliquée, Series AF, No. 7, Suppl. no. 179 (November 1966), pp. 121–4.

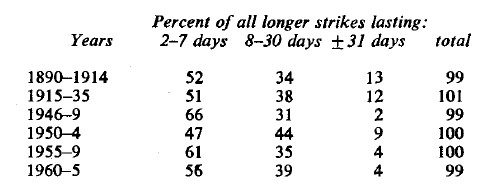

17 Data on percentage of strikes lasting less than twenty-four hours are from our own calculations from the Statistique des grèves, and from the Revue française du travail; data on weighted average duration taken entirely from the Annuaire statistique de la France; Résumé rétrospectif, 1966, pp. 120–1Google Scholar. The decline in duration of strikes since the War is due to more than the efflorescence of twenty-four hour protest strikes. Longer strikes as well are less frequent than before the War. The distribution of strikes longer than one day changed as follows:

18 Data taken from Annuaire Statistique de la France, 1966, p. 120.Google Scholar

19 As evidence of the impact of establishment size upon strike activity we present these data: in the early 1920s industrial establishments of over 500 workers represented less than 1 percent of all industrial establishments larger than six workers (798 of 88,693 establishments in 1921). Yet in the years 1920–4 these few large establishments had 12 percent of all strikes, showing the great piling up of strike activity in big plants. For a brief summary of establishment data, see Traité de sociologie du Travail, Friedmann, Georges and Naville, Pierre, eds. (Paris: Colin, 1964), Vol. 2, p. 11Google Scholar. Antoine Prost has verified the relationship between size of establishment and union organization, finding a high correlation (r = 0.77) between unionization and the industrial concentration of male workers in 1937; see his La C.G.T. à l'époque du Front Populaire, 1934–1939 (Paris: Colin, 1964), pp. 78–83. Our preliminary researches show some correlation between unionization and strike activity. In 1900–4, for example, middling correlations appear between the number of union members and number of strikes (r = 0.50), and the number of strikers (r = 0.55) by department.Google Scholar

20 The question of which single index—the number of man-days lost, strikers, or strikes—is the best measure of the volume of strike activity continues to bedevil students of strikes. In the present case merely counting the number of strikes obscures wholly the drastic decrease in the rate of man-days lost since the War. And for some purposes a knowledge of man-days lost is much more important than merely of the number of strikes, such as in assaying the economic consequences of industrial disputes. We have chosen the total number of strikes as our basic time series because it better comprises the contributions to the total of all the different industries than the number of man-days lost, a series easily dominated by the contribution of a single large, militant industry, such as mining or construction. On this problem of which series is best see Galambos, P. and Evans, E. W., ‘Work-Stoppages in the United Kingdom, 1951–1964: A Quantitative Study’, Bulletin of the Oxford University Institute of Statistics, 28 (1966), 33–57CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and especially p. 34; see also Knowles's, K. G. J. C. comment on their work, and the authors' reply, pp. 59–62 and 283–4 of that volume.Google Scholar

21 One might apply a similar procedure to the territorial units of France, and try to account for variations in their strike pictures on the basis of differences in their traditions of militancy, or the structure of their enterprises, or their distinctive cultural characteristics. This paper omits a treatment of geographical variation because the length and complexity of such an analysis make it more suitable for separate publication.

22 Kerr and Siegel have suggested an important typology of industries, arguing that the geographic isolation of an industry, rather than the mere clustering of its plants or the concentration of its workers into great mills, is the key variable in interindustry strike differentials. They also stress the arduousness of the tasks in an industry, rather than the type of its technology, as a second relevant variable. Our hypothesis about the importance of large plants in labor militancy receives empirical support from Revans, R. W., ‘Industrial Morale and Size of Unit’, Political Quarterly, 27 (1956), 303–11CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The argument that an industry's technology determines its style of conflict has a long pedigree. An important work is Blauner, Robert, Alienation and Freedom: The Factory Worker and His Industry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1964)Google Scholar; on the application of this hypothesis to France see: Touraine, Alain, Workers' Attitudes to Technical Change (n.p.: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 1965)Google Scholar; Touraine, , La conscience ouvrière (Paris: Seuil, 1966)Google Scholar; Mallet, , Nouvelle classe ouvrière, especially pp. 7–58.Google Scholar

On the distribution of various sizes of plants by industry see: de Ville-Chabrolle, Marcel, ‘La concentration des entreprises en France avant et depuis la guerre’, Bulletin de la Statistique Générate de la France, 22 (1933), 391–462Google Scholar; R. C. Marchand, ‘La concentration du personnel dans les entreprises en France entre les deux guerres’, ibid. (January-March 1945), pp. 77–100; George, Pierre, ‘Etude des dimensions des établissements industriels’, in Matériaux pour une géographie volontaire de I'Industrie française, eds., Dessus, Gabriel et al. ,. (Paris: Colin, 1949), pp. 109–43Google Scholar; I.N.S.E.E., ‘La concentration des établissements en France de 1896 à 1936’, Etudes et conjunctures, No. 9 (September 1954), pp. 840–81.

Virtually none of the systematic groundwork necessary to study the evolution of skill levels in French industry has been laid. Aside from scattered histories of single industries, no one, to our knowledge, has studied the historical relationship between technological change and worker attitudes. Our remarks on skill differentials are based upon general knowledge and impressionistic observation.

23 Here are the industrial labels the Statistique des grèves uses, along with our translations:

24 Calculations of strike rates for the year 1938 alone show the hardware-engineering and transport-tertiary sectors far ahead of other industrial groups. This would be an intriguing suggestion of modernity, were our data for the late 1930s not so unreliable.

25 The mining labor force dropped by 27 percent from 258,000 in 1954 to 189,000 in 1965. See Annuaire statistique de la France, 1966, p. 108.Google Scholar

26 Calculated on the basis of the total active population, not just the industrial labor force.

27 Before World War II the French strike rate was not at all high compared to those of other nations. As Forchheimer has shown, the French strike rate of seven per 100,000 non-agricultural labor force in the period 1900–35 was outstripped by Sweden, Germany, and the U.S.A.; over that particular long haul, France led only the United Kingdom, and tied with Canada. Thus the militant showing of the French in Figure 4 is somewhat misleading. See Forchheimer, K., ‘Some International Aspects of the Strike Movement’, Bulletin of the Oxford University Institute of Statistics, 10 (1948), 9–24CrossRefGoogle Scholar and especially p. 11. Goetz-Girey, concludes from the Forchheimer data: ‘La France est un pays óu la paix sociale est, entre les deux guerres, la mieux assurée.’ (p. 87).Google Scholar

28 Ross, and Hartman, , op. cit., pp. 89, 116.Google Scholar

29 In 1955 relatively fewer French workers were union members (25 percent of the non-agricultural labor force) than in any other western industrial nation. See ibid., p. 203.

30 Henri Bartoli sees post-war labor militancy as evidence that the French working class has not been integrated into the social system. New patterns of industrialization have produced new varieties of militancy. Bartoli illustrates his points with strike data by region and industry going up to 1965. ‘Emploi et industrialisation’, Economie appliquée: Archives de VI.S.E.A., Vol. 21, No. 1 (1968), pp. 123–236Google Scholar, and especially pp. 194–203. Raymond Aron explains this same militancy in terms of the uneveness of French industrial growth: in slower sectors worker demands piled up, exploding finally into outpourings of grievances (revendications, as the French say) through strikes. ‘Remarques sur les particularités de 1'évolution sociale de la France’, Transactions of the Third World Congress of Sociology, 3 (1956), 42–53 and especially pp. 51–3.Google Scholar