Introduction

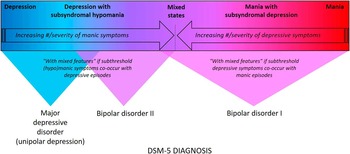

The recent addition of the mixed features specifier in the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM–5) codifies a new nosological entity characterized by subthreshold hypomanic or manic symptoms occurring during depressive episodes of either major depressive disorder (MDD) or bipolar I or bipolar II disorder. 1 The introduction of the DSM–5 mixed features specifier also reflects a growing consensus that mood disorders may be conceptualized along a spectrum ranging from pure unipolar depression, through an admixture of varying degrees and presentations of depressive and manic symptoms, to pure mania (Figure 1).Reference Benazzi 2 – Reference Solé, Garriga, Valentí and Vieta 6 Perhaps one of the greatest challenges in recognizing the existence of mixed depression or depressive mixed states (DMX) is the question of how to optimize treatment for patients with depression who exhibit concomitant subthreshold features of hypomania or mania. Although there are several guidelines available that provide recommendations for the treatment of unipolar depression, for bipolar depression, and for bipolar mania, there is currently only one treatment guideline that has provided decision support for individuals presenting with a major depressive episode with mixed features (i.e., the Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults [2015], available for download at http://www.medicaidmentalhealth.org/_assets/file/Guidelines/Web_2015-Psychotherapeutic%20Medication%20Guidelines%20for%20Adults_Final_Approved1.pdf).Reference Cerullo and Strakowski 7 – Reference Fountoulakis, Grunze and Vieta 19 In fact, any treatment guidelines developed prior to the release of the DSM–5 that mention “mixed states” are based on the previous DSM–IV diagnostic criteria that refer to co-occurring full-blown, threshold-level depression with full-blown, threshold-level mania (mixed mania) and simply lump mixed states together with bipolar mania in terms of treatment recommendations.Reference Grunze and Azorin 20

Since the release of the DSM–5 in 2013, it has been suggested that clinicians follow existing guidelines written for the treatment of MDD or bipolar disorder (BD) without any particular reference to individuals presenting with depressive episodes with mixed (DMX) features. However, not only is DMX different in its clinical presentation compared to an MDE, it is not pathognomonic of either MDD or BD. Toward the aim of filling the gaps between updated diagnostic criteria, the latest research findings, and optimal clinical practice, we have gathered together a panel of experts on mood disorders to develop a set of guidelines for the recognition and treatment of DMX.

The guideline recommendations throughout this article are made in reference to DSM–5 rather than DSM–IV descriptions and criteria. However, the diagnostic criteria warranting a DSM–5 major depressive episode (MDE) with mixed features diagnosis exclude “overlapping symptoms” of irritability, distractibility, insomnia, and psychomotor agitation as defining of the opposite polarity due to the presence of these symptoms in both mania and depression. The exclusion of overlapping symptoms increases the specificity of the diagnosis at the expense of sensitivity and possibly face validity insofar as most individuals presenting with an MDE and mixed features do present with “overlapping symptoms.”Reference Takeshima and Oka 21 – Reference Sani, Vohringer and Napoletano 31 The potential of DMX being misdiagnosed and treated as pure unipolar depression is far greater than if unipolar depression is misdiagnosed and mistreated as DMX).

Overview and Key Points

-

∙ Not all patients with depression (as part of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder) should be prescribed an antidepressant.

-

∙ All patients who receive antidepressants for an MDE should be monitored for signs of abnormal behavioral activation or psychomotor acceleration.

-

∙ The use of antidepressants in MDE patients with mixed features may not alleviate depressive symptoms and may pose a potential hazard for exacerbating subthreshold mania symptoms that accompany depression.

-

∙ For an individual presenting with a depressive episode with mixed features, in addition to antidepressant medication, alternative psychotropic agents (e.g., lithium, anticonvulsant mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics) with demonstrated efficacy in treating depressive symptoms as part of MDE may be considered.

-

∙ You will not know if a depressed patient has (hypo)manic symptoms or a positive family history of bipolar disorder unless you ask! Ask every patient. Every time.

Assessment

DSM–5 diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode 1 (consider an itemized depression screener such as the Quick Inventory Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report or Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale)

-

∙ EITHER depressed mood OR anhedonia/loss of interest AND four (or more) of the following symptoms:

-

➢ Weight/appetite changes

-

➢ Sleep disturbances

-

➢ Psychomotor agitation or retardation

-

➢ Fatigue

-

➢ Worthlessness or guilt

-

➢ Executive dysfunction

-

➢ Suicidal ideation or thoughts of death

-

-

∙ May be part of unipolar depression, bipolar II depression, or bipolar I depression

DSM–5 diagnostic criteria for the mixed features specifier 1

-

∙ Full criteria for a major depressive episode and at least three of the following (hypo)manic symptoms during the majority of days of the current or most recent depressive episode:

-

➢ Elevated, expansive mood

-

➢ Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

-

➢ More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

-

➢ Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

-

➢ Increase in energy or goal-directed activity

-

➢ Increased or excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences

-

➢ Decreased need for sleep (to be contrasted with insomnia)

-

-

∙ May be part of unipolar depression, bipolar II depression, or bipolar I depression

Non DSM–5 diagnostic criteria for mixed depression (overlapping symptoms) Reference Benazzi 2 , Reference Takeshima and Oka 21 – Reference Malhi, Lampe and Coulston 23 , Reference Faedda, Marangoni and Reginaldi 25 , Reference Perugi, Angst and Azorin 29

-

∙ Controversy exists as to whether the symptoms of DMX are fully captured by the DSM–5 diagnostic criteria, as well as the extent to which DMX symptoms can be differentiated from comorbid disorders or other conditions, including borderline personality disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorderReference Perugi, Angst and Azorin 29 , Reference Goldberg 32

-

∙ Alternative diagnostic criteria have been proposed and focus on the most common symptoms seen in patients with DMX, including:

-

➢ Irritability

-

➢ Anxiety

-

➢ Distractibility

-

➢ Psychomotor agitation

-

➢ Racing/crowded thoughts

-

➢ Initial and middle insomnia

-

➢ Indecisiveness

-

➢ Anger

-

➢ Increased talkativeness

-

➢ Emotional lability/tearfulness

-

➢ Inner tension

-

➢ Rumination

-

➢ Initial or middle insomnia

-

➢ Impulsivity

-

➢ Risky behaviors

-

-

∙ These alternative diagnostic criteria for DMX also stress how critical it is to assess the patient for any family history of bipolar spectrum disorders:Reference Prieto, Youngstrom and Ozerdem 33 – Reference Akiskal and Benazzi 35

-

➢ Always inquire about family history of bipolar symptoms or ANY symptoms of (hypo)mania in patients presenting with a major depressive episode

-

➢ Inquire about common bipolar comorbidities (e.g., migraine, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, obesity, binge eating, ADHD). Although these comorbidities are observed in both BD and MDD populations, data suggest that patients with BD (especially those with BDII and pediatric populations) are more likely to be affectedReference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17 , Reference Brietzke, Moreira and Duarte 36 – Reference Jerrell, McIntyre and Tripathi 39

-

Differential Diagnosis

-

∙ The prognosis for depression with cooccurring subthreshold hypomania (DMX) is much worse than for pure unipolar depression or bipolar depression without mixed featuresReference Goldberg, Perlis and Bowden 26 , Reference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 40

-

∙ A significant minority (about 13–20%) of individuals with unipolar DMX will eventually meet diagnostic criteria for bipolar I or bipolar II disorder

-

∙ In order to avoid treatments that could worsen symptoms of hypo/mania in MDE patients with mixed features (e.g., antidepressant monotherapy), to prevent the development of resistance to appropriate treatments, and to avert treatment-emergent affective switch (TEAS), it is essential that DMX be distinguished from pure unipolar depression as early as possibleReference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 40 – Reference Post, Leverich and Altshuler 45

-

∙ A key differential diagnostic issue is unipolar depression with borderline personality disorder versus DMX. Most of the correlates listed below are also correlates of unipolar depression with borderline personality disorder

-

∙ MDD with active substance use disorders could inflate rates of false-positive detection of hypo/mania symptoms and requires a careful longitudinal historyReference Goldberg, Garno, Callahan, Kearns, Kerner and Ackerman 46

-

∙ DMX has been associated with:

-

➢ Family history of bipolar spectrum disorders

-

➢ Suicidality

-

➢ Antidepressant-induced mania

-

➢ Rapid cycling

-

➢ Young age of onset

-

➢ Long duration of illness

-

➢ Poor prognosis

-

➢ Severe depression

-

➢ Antidepressant resistance

-

➢ Females

-

➢ Comorbid anxiety

-

➢ Comorbid substance-use disorder (SUD)

-

➢ Impulse control disorders

-

-

∙ There are several assessment tools available to aid in the recognition of subthreshold hypomanic symptoms, including:

-

➢ Bipolar Depression Rating Scale (BDRS)Reference Galvao, Sportiche and Lambert 47

-

ʘ Clinician-administered assessment of current symptoms

-

-

➢ Hypomania Interview Guide (HIG)Reference Williams, Terman, Link, Amira and Rosenthal 48 , Reference Benazzi 49

-

ʘ Clinician-administered assessment of current symptoms

-

-

➢ Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)Reference Hergueta and Weiller 50

-

ʘ Patient self-report assessing current (hypo)manic symptoms

-

-

➢ Clinically Useful Depression Outcome Scale with DSM–5 Mixed (CUDOS–M)Reference Zimmerman, Chelminski, Young, Dalrymple and Martinez 51

-

ʘ Patient self-report assessing current (hypo)manic symptoms

-

-

➢ Hypomania Checklist (HCL–32)Reference Prieto, Youngstrom and Ozerdem 33 , Reference Altinbas, Ozerdem and Prieto 52

-

ʘ Patient self-report that screens for lifetime (hypo)manic symptoms—this does not assess mixed episodes, and has not been suggested to do so

-

-

➢ Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ)Reference Hirschfeld, Williams and Spitzer 53

-

ʘ Patient self-report that screens for lifetime (hypo)manic symptoms

-

-

➢ Altman Mania Rating ScaleReference Altman, Hedeker, Peterson and Davis 54

-

ʘ Patient self-report assessing current (hypo)manic symptoms

-

-

-

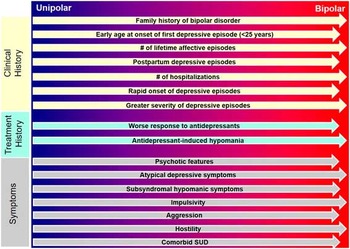

∙ Patient self-report that screens for “bipolar spectrum disorder” (which includes bipolar I and bipolar II), and the “probabilistic” approach may help to identify patients who are more likely to have a bipolar spectrum disorder rather than pure unipolar depression (Figure 2)

-

➢ The same factors that indicate bipolarity are also evident in patients with DMX

-

-

∙ Rule out comorbid conditions that phenotypically overlap with mixed features and/or secondary causes of (hypo)mania, but keep in mind that some secondary causes (e.g., substance use) could be more frequent among individuals with bipolar than unipolar disorder

-

➢ Drug and/or alcohol misuse

-

ʘ If comorbid, the mood state will generally precede and significantly outlast the state induced by intoxication or withdrawal, and a diagnosis of bipolar disorder can be made

-

-

➢ Certain medications

-

ʘ e.g., L-dopa and corticosteroids, stimulants

-

-

➢ Organic conditions

-

ʘ Most likely in older patients

-

-

➢ Caffeine use

-

➢ Infections (HIV, syphilis, other)

-

➢ Multiple sclerosis

-

➢ Traumatic brain injury (TBI), brain lesion(s) involving subcortical or cortical areas

-

➢ Thyroid disease

-

➢ Disruptive behavior disorders (CD, ODD)

-

➢ Cyclothymic temperament, novelty seeking, narcissistic and borderline personality disorders

-

➢ Agitated or anxious depression

-

ʘ It has been proposed that agitated depression (a major depressive episode with psychomotor agitation) is a form of mixed depression because it often occurs along with other symptoms of hypomaniaReference Koukopoulos and Sani 22 , Reference Olgiati, Serretti and Colombo 27 , Reference Akiskal, Benazzi, Perugi and Rihmer 55

-

-

Baseline Medical History and Laboratory Parameters 11 , Reference Ng, Mammen and Wilting 56

-

∙ Medical history

-

∙ Smoking history

-

∙ Cardiometabolic family history

-

∙ Waist circumference and/or BMI

-

∙ Blood pressure

-

∙ Complete blood count (CBC)

-

∙ Electrolytes, urea, and creatinine (EUC)

-

∙ Urine toxicology for substance use

-

∙ Fasting glucose

-

∙ Fasting lipid profile (TC, vLDL, LDL, HDL, TG)

-

∙ Liver enzymes

-

∙ Hepatitis A, B, C; syphilis testing in patients deemed at risk

-

∙ Estimated glomerular filtration rate

-

∙ Platelets

-

∙ Thyroid-stimulating hormone

-

∙ Serum bilirubin

-

∙ Electrocardiogram (>40 years or if indicated)

-

∙ Prolactin (if relevant)

-

∙ Pregnancy test (if relevant)

-

∙ Contraceptive use (if relevant)

Treatment

Initial treatment

-

∙ Antidepressant monotherapy should probably NOT be utilized for patients with mixed depression of any type (unipolar, BP II, or BP I), given persisting doubts about the relative efficacy of standard antidepressants in treating bipolar disorders and their potential to destabilize moodReference Cerullo and Strakowski 7 , Reference Cleare, Pariante and Young 8 , 11 , Reference Grunze, Vieta and Goodwin 12 , Reference Faedda, Marangoni and Reginaldi 25 , Reference Goldberg 32 , Reference Akiskal and Benazzi 57 – Reference Pae, Vohringer and Holtzman 68

-

➢ It is critical that patients presenting with a major depressive episode be assessed for the presence of any symptoms of (hypo)mania and family history of mood disorder, including bipolar disorder, before initiating treatment

-

➢ Patients with mixed depression should be monitored regularly for the emergence or worsening of (hypo)mania and suicidality

-

➢ Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) may carry the highest risk of causing a treatment-emergent affective switch, 11 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17 , Reference Sani, Napoletano and Vohringer 30 , Reference Bjorklund, Horsdal, Mors, Ostergaard and Gasse 62 , Reference Gijsman, Geddes, Rendell, Nolen and Goodwin 63 , Reference Patel, Reiss and Shetty 69 – Reference Tundo, Calabrese, Proietti and de Filippis 73 while bupropion and some selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may have a lower risk of affective switch

-

➢ There is some evidence for the adjunctive use of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the treatment of bipolar depressionReference Grunze 74 , Reference Heijnen, De Fruyt, Wierdsma, Sienaert and Birkenhager 75

-

➢ For symptomatic patients with mixed depression, antidepressant monotherapy should generally be tapered and discontinued. Clinicians should carefully assess whether mixed features may be exacerbated by antidepressant monotherapies; in such instances, consideration should be given either to augmentation with an atypical antipsychotic or antimanic mood stabilizer (e.g., lithium, divalproex, carbamazepine) or else tapering and discontinuing antidepressants altogether if deemed ineffective

-

-

∙ There are currently no psychotropic agents that are FDA- or EMA-approved for the treatment of depression with mixed features

-

∙ First-generation antipsychotics and sedatives (benzodiazepines, hypnotics) have been used successfully in the treatment of depressive mixed states

-

∙ Atypical antipsychotics (including asenapine,Reference Berk, Tiller, Zhao, Yatham, Malhi and Weiller 76 , Reference McIntyre, Tohen, Berk, Zhao and Weiller 77 lurasidone,Reference McIntyre, Cucchiaro, Pikalov, Kroger and Loebel 78 , Reference Suppes, Silva and Cucchiaro 79 olanzapine,Reference Tohen, Kanba, McIntyre, Fujikoshi and Katagiri 80 quetiapine,Reference Suppes, Ketter and Gwizdowski 81 and ziprasidoneReference Patkar, Gilmer and Pae 82 ) are the only psychotropic agents that have been specifically tested (and shown some efficacy) for the treatment of depression with mixed features

-

➢ Not all atypical antipsychotics have demonstrated efficacy in bipolar depression (e.g., Lombardo et al., 2009Reference Lombardo, Sachs, Kolluri, Kremer and Yang 83 ). Caution is therefore warranted when extrapolating to DMX from outcome studies in frank bipolar disorder. Moreover, these studies did not enroll subjects according to the DSM–5 definition of mixed features

-

➢ Cariprazine and aripiprazole have also both shown some efficacy in improving both manic and depressive symptomsReference Takeshima 84 , Reference Kelly and Lieberman 85

-

➢ The efficacy of the atypical antipsychotics listed above is suggested largely based on post-hoc analyses of mixed mania in BDI (i.e., DMX with severe manic symptoms)

-

➢ Dose ranges of the atypical antipsychotics suggested in Table 1 may be too strongly sedative for mild to moderate DMX

-

-

∙ No mood stabilizer (lithium and divalproex) is actually approved for use in depression of any kind (unipolar, mixed, bipolar),Reference Stahl 86 except lamotrigine, which is approved for maintenance treatment in bipolar I disorderReference Connolly and Thase 9 , 11 , Reference Musetti, Del Grande, Marazziti and Dell’Osso 14 , Reference Fountoulakis, Kasper and Andreassen 71

-

➢ Lithium has traditionally been considered an effective antidepressant treatment augmentation strategy, and often very low doses of lithium can be effective for selected patients

-

➢ Lithium is well-known for its anti-suicide, anti-aggression, anti-cycling, and antimanic effects. However, lithium also may yield less favorable effects as compared to divalproex in bipolar mixed states.Reference Swann, Bowden and Morris 87 The efficacy of lithium in bipolar depression and especially mixed depression has not been adequately investigated

-

Patients failing to respond to monotherapy and continuing to experience subthreshold symptoms or relapses

-

∙ The treatment of DMX may require a combination of medicationsReference Nivoli, Murru and Goikolea 15 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Schaffer 18 , Reference Benazzi, Berk, Frye, Wang, Barraco and Tohen 60 , Reference Grunze 74 , Reference Magiria 88

-

➢ Combinations with potential efficacy in DMX:

-

ʘ Atypical antipsychotic + mood stabilizer

-

ʘ Atypical antipsychotic + antidepressant

-

ʘ Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination in particular (caution in overweight or obese patients and those with metabolic dysregulation)

-

ʘ Mood stabilizer + antidepressant

-

-

➢ If an antidepressant is prescribed for DMX, it should be used in conjunction with a mood-stabilizing agent (atypical antipsychotic or mood stabilizer); however, it is questionable whether adding an antidepressant to a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic has therapeutic benefit in bipolar disorder patientsReference Goldberg, Perlis and Ghaemi 89

-

➢ (Hypo)manic symptoms, irritability, dysphoric mood, and insomnia can deteriorate or develop during antidepressant treatment even in conjunction with mood-stabilizing agentsReference Goldberg, Perlis and Ghaemi 89 , Reference Ei-Mallakh and Karippot 90

-

➢ The role of antidepressants in long-term treatment is controversial and not established by controlled trials in DMX, but they may be used effectively in a small minority of patients in the long term, 11 particularly if there is a robust initial response or remission without signs of mood destabilizationReference Altshuler, Post and Hellemann 91

-

➢ The combination of olanzapine or risperidone with carbamazepine is not recommended due to potent pharmacokinetic induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes by carbamazepineReference Nivoli, Murru and Goikolea 15

-

-

∙ The use of additional short-term medication (e.g., benzodiazepines) may be necessary when an acute stressor is imminent or present, early symptoms of relapse (especially insomnia) occur, or anxiety becomes prominent

-

∙ Addition of hypnotics for the treatment of insomnia unresponsive to mood disorder medications may be helpful/necessary

-

∙ Higher doses of the long-term treatments may also be effective, thus avoiding the need for additional medications

-

∙ Ensure adequate doses of medicines and that serum levels of lithium and valproate are within the therapeutic range

-

∙ Address use of alcohol or illicit psychoactive substances that can destabilize mood

-

∙ Address current stressors; consider psychosocial interventions in general, particularly those targeting lifestyle/daily rhythms, e.g., interpersonal social rhythm therapy (IPSRT)

-

∙ If the patient fails to respond to optimization of long-term treatment, consider augmentation or change of treatmentReference Connolly and Thase 9 , 11 , Reference Grunze, Vieta and Goodwin 12 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17

-

➢ There are some limited data supporting the adjunctive use of L-thyroxine,Reference Bauer, Berman and Stamm 92 , Reference Stamm, Lewitzka and Sauer 93 N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC),Reference Fernandes, Dean, Dodd, Malhi and Berk 94 , Reference Berk, Dean and Cotton 95 omega-3 fatty acids,Reference Sarris, Mischoulon and Schweitzer 96 ramelteon,Reference Geoffroy, Etain, Franchi, Bellivier and Ritter 97 celecoxib,Reference Faridhosseini, Sadeghi, Farid and Pourgholami 98 modafinil,Reference Corp, Gitlin and Altshuler 99 , Reference Goss, Kaser, Costafreda, Sahakian and Fu 100 inositol,Reference Taylor, Wilder, Bhagwagar and Geddes 101 , Reference Mukai, Kishi, Matsuda and Iwata 102 ketamine,Reference Kraus, Rabl and Vanicek 103 , Reference McCloud, Caddy and Jochim 104 and pramipexoleReference Dell’Osso and Ketter 105 in the treatment of bipolar depression

-

-

∙ Consider electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with high suicidal risk, psychosis, severe depression during pregnancy, or life-threatening inanition. Consider simplifying preexisting polypharmacy, reducing drug-to-drug interactions; might lead to changes in seizure thresholds 11 , Reference Faedda, Marangoni and Reginaldi 25

-

∙ Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) may also have some efficacy in treating mixed depression; however, this supposition is based on “off-label” data from preliminary trials in bipolar depression; attempt TMS only after other options have been triedReference Grunze 74

Maintenance treatment 11 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17 , Reference Fountoulakis, Kasper and Andreassen 71 , Reference Grunze 74 , Reference Muneer 106

-

∙ In an individual patient, if one of the recommended acute treatments led to prompt remission from the most recent mixed depressive episode, this may be considered evidence in favor of its long-term use as monotherapy

-

∙ The preferred strategy is for continuous rather than intermittent treatment with oral medication to prevent new episodes

-

∙ Without active acceptance of the need for long-term treatment, adherence may be poor; consider offering enhanced psychological and social support

-

∙ Consistent outpatient follow-up is necessary

-

∙ Long-term treatment is indefinite for the prevention of new episodes and to achieve adequate inter-episode control of residual or chronic mood symptoms

-

∙ Because of the high risk of relapse and the apparent progression to more frequent episodes, long-term treatment with appropriate medication is advocated from as early in the illness course as is acceptable to a patient and his or her family

-

∙ Remain vigilant to conversion to bipolar disorder of patients whose index episode is diagnosed as unipolar DMX

-

∙ In the absence of convincing evidence in favor of long-term treatment with antidepressants, the usual policy should be eventual discontinuation, although a small minority of patients have a robust initial antidepressant response and appear to do well on long-term combination treatment that includes an antidepressantReference Goldberg, Perlis and Ghaemi 89

Safety monitoringReference Ng, Mammen and Wilting 56

-

∙ Suicide is the main serious safety concern in this population, and an individualized approach is necessary depending on clinical variables, social support, and preexisting suicide risk factors

-

∙ Take all possible steps to protect and improve the physical health of patients in your care through active screening and treatment of risk factors or declared disease

-

∙ Higher morbidity and mortality have been reported in bipolar patients, even before treatment with psychotropic agents was initiated. It is of growing concern that many of the long-term treatments that appear to be required for mixed depression may add to the burden of physical disease

-

∙ In addition to baseline laboratory measurements, patients should be monitored continually for the development of adverse events specific to the treatment(s) utilized

-

∙ The risk of tardive dyskinesia is significantly increased with the use of antipsychotics and should be monitored for regularly

Discontinuation of treatmentsReference Connolly and Thase 9 , 11 , Reference Nivoli, Murru and Goikolea 15

-

∙ Following discontinuation of medicines, the risk of relapse remains, even after years of sustained remission; accordingly, if considered, it should be accompanied by an informed assessment of the potential costs and dangers

-

∙ Discontinuation of any long-term medication should normally be tapered over at least two weeks and preferably longer. Early relapse to mania in bipolar disorder patients is a risk of abrupt lithium discontinuation. Clinical monitoring during treatment withdrawal is desirable

-

∙ When a patient has accepted treatment for several years and remains very well, he or she should be strongly advised to continue indefinitely, as the risk of relapse remains high

Children and adolescentsReference Grunze, Vieta and Goodwin 12 , Reference Woo, Lee and Jeong 16 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17 , Reference Axelson, Goldstein and Goldstein 34 , Reference Rihmer and Gonda 43 , Reference Ng, Mammen and Wilting 56 , Reference Benazzi 61 , Reference Rihmer and Akiskal 70 , Reference Dilsaver, Benazzi and Akiskal 107 , Reference Dilsaver, Benazzi, Rihmer, Akiskal and Akiskal 108

-

∙ The clinical features of childhood mood disorders often differ from those in adults

-

∙ Child and adolescent mood disorders are often comorbid with attention deficit and conduct disordersReference Thapar, Collishaw, Pine and Thapar 109

-

∙ Mixed depression is especially common in children and adolescentsReference Angst, Cui and Swendsen 40 , Reference Singh, Ketter and Chang 110

-

∙ The risk of antidepressant-induced suicidality may be highest in the pediatric population due to the presence of mixed featuresReference Rihmer and Gonda 43 , Reference Akiskal and Benazzi 57 , Reference Balazs, Benazzi, Rihmer, Rihmer, Akiskal and Akiskal 59 , Reference Rihmer and Akiskal 70 , Reference Dilsaver, Benazzi, Rihmer, Akiskal and Akiskal 108

-

➢ Children and adolescents presenting with major depression should be screened and monitored for any (hypo)manic symptoms, suicidality, and family history of mood disorders

-

➢ Antidepressant monotherapy should be avoided in children and adolescents until any presence of (hypo)mania or positive family history of bipolar spectrum disorder is ruled out

-

-

∙ With the exception of fluoxetine, the evidence for efficacy of antidepressants in treating major depressive disorder in the pediatric population is not robustReference Cipriani, Zhou and Del Giovane 111

-

∙ Venlafaxine may have the highest risk of increasing suicidality in children and adolescentsReference Cipriani, Zhou and Del Giovane 111

Women of child-bearing potential 11 , Reference Yatham, Kennedy and Parikh 17 , Reference Ng, Mammen and Wilting 56

-

∙ The postpartum period is a time of very high risk of relapse or recurrence into severe illness in women with mood disorders. Vigilance and close monitoring during the perinatal period is essential, and effective prophylactic treatment should be considered

-

∙ In pregnancy, there is a risk of teratogenicity from a number of medications used in all phases of treatment. Higher teratogenic risks appear to be associated with certain anticonvulsants (notably, valproate and carbamazepine). Lithium has also been associated with teratogenicity, although prospective studies suggest that the risk is lower than originally described. The lowest risks appear to be associated with the antipsychotics. However, risks for new compounds are usually unknown and always justify caution

-

∙ Many psychotropics can cause symptoms in neonates (including discontinuation effects from, e.g., antipsychotics, SSRIs). Neonates should be monitored for possible adverse effects following birth. Long-term effects on cognitive development have been reported with exposure to valproate in pregnancy

-

∙ However, optimization of maternal mental health remains a key determinant of pregnancy outcomes; thus, effective treatment of the mother must be carefully weighed against potential risks to the neonateReference Cohen, Wang, Nonacs, Viguera, Lemon and Freeman 112

-

∙ Discontinuation or switching medications risks destabilizing mood and precipitating relapse. Any risk putatively associated with the use of medications should be considered in the context of the relatively high age-related background risk for congenital malformations and spontaneous abortion in the general population

-

∙ If a mother takes medication and breastfeeds, the infant should be monitored for possible adverse effects

-

∙ Medications with a high risk in pregnancy such as valproate or carbamazepine should not be used routinely if there is a significant likelihood of pregnancy

Enhanced careReference Connolly and Thase 9 , 11 , Reference Grunze, Vieta and Goodwin 12 , Reference Faedda, Marangoni and Reginaldi 25

-

∙ Make use of evidence to address poor insight, the seriousness of the illness, reluctance to give up the experience of hypo(mania), the risk of relapse, and the benefit of therapeutic engagement

-

∙ While respecting patient preferences, education about the illness should emphasize the long-term need for medicines

-

∙ Help the patient, family members, and significant others recognize the signs and symptoms of mixed depressive episodes for early treatment; family psychoeducation may improve treatment outcomes

-

∙ Psychosocial interventions enhance care, which can increase adherence and reduce the risk of relapse

-

∙ A large and comprehensive program of psychoeducation may be superior to an equivalent time spent in nonspecific talking therapy

-

∙ Interpersonal and family therapy as well as cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial

-

∙ Group psychoeducation may also be more effective than cognitive behavioral therapy for some patients

-

∙ Internet-based psychosocial interventions may be helpful and hold promise, particularly with respect to accessibility

-

∙ A consistent long-term flexible alliance among the patient, the patient’s family, and one effective clinician is the ideal arrangement for outpatient care in patients whose condition has been effectively stabilized. Patients’ relatives should feel comfortable contacting the clinician to report escalations of symptoms or other emergencies

-

∙ Known tolerability of available medicines should guide prescribing:

-

➢ Inform patients about possible side effects and monitor their possible emergence

-

➢ Make side effect reduction a priority by lowering the dose, by employing different scheduling (e.g., prescribing all sedative medicines at bed time), or by using alternative formulations

-

➢ Some patients with mixed depression may require or tolerate lower doses of mood-stabilizing drugs than those used for threshold-level mania

-

Disclosures

Stephen M. Stahl has served as a consultant to Acadia, Allergan, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Avanir, Axovant, Axsome, Biogen Celgene, Forest, Forum, Genomind, Innovative Science Solications, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, PamLabs, Pierre Fabre, Reviva, Servier, Shire, Spout, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, Tonix, and Vanda; and he is board member of Genomind. He has served on speakers bureaus for Forum, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier, Sunovion, and Takeda. He has received research and/or grant support from Arcadia, Actavis, Alkermes, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, Avanir, Axovant, Biogen, Celegen, Eli Lilly, Forest, Forum, Jazz, Lundbeck, Merck, Otsuka, Reviva, Servier, Shire, Sprout, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, Tonix and Vanda.

Debbi Morrissette has nothing to disclose.

Gianni Faedda has the following disclosure. Manhattan Behavioral Medicine: owner and principal investigator in clinical trials site.

Maurizio Fava has the following disclosures. Research Support: Abbott Laboratories, Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes Inc., American Cyanamid, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, AXSOME Therapeutics, BioResearch, Braincells Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Cerecor, Clintara LLC, Covance, Covidien, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals Inc., Euthymics Bioscience Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., FORUM Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Harvard Clinical Research Institute, Hoffman-LaRoche, Icon Clinical Research, i3 lnnovus/lngenix, Janssen R&D LLC, Jed Foundation, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck Inc., MedAvante, Methylation Sciences Inc., National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), National Coordinating Center for Integrated Medicine (NiiCM), National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Neuralstem Inc., NeuroRx, Novartis AG, Organon Pharmaceuticals, PamLab LLC, Pfizer Inc., Pharmacia & Upjohn Company LLC, Pharmaceutical Research Associates Inc., Pharmavite® LLC, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Reckitt Benckiser, RCT Logic LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions LLC), Roche Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis US LLC, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc., Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI), Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Tal Medical, VistaGen, Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories Advisory Board. Consultant: Abbott Laboratories, Acadia, Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG, Alkermes Inc., Amarin Pharma Inc., Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Avanir Pharmaceuticals, AXSOME Therapeutics, Bayer AG, Best Practice Project Management Inc., Biogen, BioMarin Pharmaceuticals Inc., Biovail Corporation, BrainCells Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon Inc., Cerecor, CNS Response Inc., Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Cypress Pharmaceutical Inc., DiagnoSearch Life Sciences (P) Ltd ., Dinippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Inc., Dov Pharmaceuticals Inc., Edgemont Pharmaceuticals Inc., Eisai Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals Inc., ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals Inc., Euthymics Bioscience Inc., Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., Forum Pharmaceuticals, GenOmind LLC, GlaxoSmithKline, Grunenthal GmbH, lndivior, i3 lnnovus/lngenis, Intracellular, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Jazz Pharmaceuticals Inc., Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC, Knoll Pharmaceuticals Corp., Labopharm Inc., Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck Inc., MedAvante Inc., Merck & Co. Inc., MSI Methylation Sciences Inc., Naurex Inc., Nestlé Health Sciences, Neuralstem Inc., Neuronetics Inc., NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis AG, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics Inc., Organon Pharmaceuticals, Osmotica, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab LLC, Pfizer Inc., PharmaStar, Pharmavite® LLC, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals Inc., PPD, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences Inc., RCT Logic LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions LLC), Rexahn Pharmaceuticals Inc., Ridge Diagnostics Inc., Roche, Sanofi-Aventis US LLC, Sepracor Inc., Servier Laboratories, Schering-Plough Corporation, Shenox Pharmaceuticals, Solvay Pharmaceuticals Inc., Somaxon Pharmaceuticals Inc., Somerset Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals Inc., Synthelabo, Taisho Pharmaceutical Company, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, Tai Medical Inc., Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals Inc., TransForm Pharmaceuticals Inc., Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc., VistaGen. Speaking/Publishing: Adamed Co., Advanced Meeting Partners, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, AstraZeneca, Belvoir Media Group, Boehringer lngelheim GmbH, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cephalon Inc., CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Pharmaceuticals Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, lmedex LLC, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, Novartis AG, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer Inc., PharmaStar, United BioSource Corp., Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. Stock/Other Financial Options: Equity Holdings: Compellis, PsyBrain Inc. Royalty/Patent, other income: patents for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), licensed by MGH to Pharmaceutical Product Development LLC (PPD), and patent application for a combination of Ketamine plus Scopolamine in Major Depressive Disorder (MOD), licensed by MGH to Biohaven. Copyright for the MGH Cognitive & Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), Sexual Functioning Inventory (SFI), Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Discontinuation–Emergent Signs & Symptoms (DESS), Symptoms of Depression Questionnaire (SDQ), and SAFER; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Wolters Kluwer; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

Joseph Goldberg has the following disclosures. Merck: speakers bureau, speaker’s fee. Sunovion: speakers bureau and consultant, speaker’s fee and consulting fee. Supernus: speakers bureau and consultant, speaker’s fee and consulting fee. Medscape: consultant consulting fee. WebMD: consultant, consulting fee. Otsuka: speakers bureau and consultant, speaker’s fee and consulting fee. Vanda Pharmaceuticals: speakers bureau, speaker’s fee. WebMD: consultant, consulting fee.

Paul Keck has the following disclosures. Otsuke: advisory board, personal fees. Shire: advisory board, personal fees.

Yena Lee has nothing to disclose.

Gin Malhi reports grants from NHMRC, personal fees from Astrazeneca, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Janssen-Cilag, personal fees from Servier, other from Melbourne University, personal fees from Elsevier, grants from Ramsay Research and Teaching Fund, grants from American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, grants from Australian Rotary Health, outside the submitted work.

Ciro Marangoni has nothing to disclose.

Susan McElroy reports personal fees from Bracket, personal fees from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., personal fees from MedAvante, personal fees from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America, grants and personal fees from Myriad, grants and personal fees from Naurex, grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, grants and personal fees from Shire, grants and personal fees from Sunovion, grants from Alkermes, grants from Forest, grants from Marriott Foundation, grants from National Institute of Mental Health, grants from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd., outside the submitted work.

Roger McIntyre has the following disclosures. Advisory Boards: Lundbeck, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Elli-Lilly, JanssenOrtho, Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, Moksha8, Sunovion, Mitsubishi, Takeda, Forest, Otsuka, Bristol-Myers Squibb. Speakers Fees: Lundbeck, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Elli-Lilly, JanssenOrtho, Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, Moksha8, Sunovion, Mitsubishi, Takeda, Forest, Otsuka, Bristol-Myers Squibb. Research Grants: Lundbeck, JanssenOrtho, Shire, Purdue, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Otsuka. Others: Allergan: research grants, patents. Shire: speaker’s fees, profit-sharing agreements. Shire: advisory boards, speaker’s fees, equity ownerships. Shire: research profit-sharing agreements

Michael Ostacher reports personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Johnson & Johnson, personal fees from Supernus Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Acadia Pharmaceuticals, grants from Palo Alto Health Sciences, outside the submitted work.

Joshua Rosenblat has nothing to disclose.

Eva Solé has nothing to disclose.

Trisha Suppes reports grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, grants from the VA Cooperative Studies Program, grants from Pathways Genomics, grants from Stanley Medical Research Institute, personal fees from Medscape Education, personal fees from Global Medical Education, personal fees from CMEology, personal fees from Jones and Bartlett, personal fees from UpToDate, grants and personal fees from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc., grants from Elan Pharma International Limited, personal fees from H. Lundbeck A/S, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Merck & Co., outside the submitted work.

Minoru Takeshima reports personal fees from Astellas, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Meiji Seika Pharma, Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, and Yoshitomi, outside the submitted work.

Michael Thase has the following disclosures. Alkermes: personal fees, consultant. AstraZeneca: consultant, personal fees. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company: personal fees, consultant. Eli Lilly & Company: grant, consultant, personal fees. Forest Laboratories: grant, consultant, personal fees. Gerson Lehman Group: consultant, grant, personal fees. GlaxoSmithKline: consultant, personal fees. Guidepoint Global: consultant, personal fees. H. Lundbeck A/S: consultant, personal fees. MedAvante: consultant; equity holdings, personal fees. Merck and Company: consultant, personal fees. Neuronetics Inc.: consultant, personal fees. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals: consultant, personal fees. Otsuka: consultant grant and personal fees. Pfizer: consultant, personal fees. Roche: consultant, personal fees. Shire US Inc.: consultant, personal fees. Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc.: consultant, personal fees. Takeda: consultant, personal fees. American Psychiatric Foundation: royalties. Guilford Publications: royalties. Herald House: royalties. W.W. Norton & Company Inc.: royalties. Peloton Advantage: other spouse’s employment (salary). Cerecor Inc.: consultant, personal fees. Moksha8: consultant, personal fees. Pamlab LLC (Nestlé): consultant, personal fees. Allergan: consultant, personal fees. Trius Therapeutical Inc.: consultant, personal fees. Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals Inc.: consultant, personal fees.

Eduard Vieta has the following disclosures. Ab-Biotics: grant and personal fees. Acatis grant and personal fees. Allergen: grant and personal fees. AstraZeneca: grant and personal fees. Bristol-Myers Squibb: grant and personal fees. Ferrer: grant and personal fees. Forest Research Institute: grant and personal fees. Gedeon Richter: grant and personal fees. Glaxo-Smith Kline: grant and personal fees. Janssen: grant and personal fees. Lundbeck: grant and personal fees. Otsuka: grant and personal fees. Pfizer: grant and personal fees. Roche: grant and personal fees. Sanofi-Aventis: grant and personal fees. Servier: grant and personal fees. Sunovion: grant and personal fees. Takeda: grant and personal fees. Telefónica: grant and personal fees. The Brain and Behaviour Foundation: grant. The Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (CIBERSAM), grant. The Stanley Medical Research Institute, grant.

Allan Young has the following disclosures. Sunovion: personal fees. Lundbeck: personal fees. Eli Lilly: personal fees. AstraZeneca: personal fees. Livanova: personal fees. Jansen: grant.

Mark Zimmerman has nothing to disclose.

Figure 1 Mood disorders spectrum and DSM–5 diagnosis. Mood disorders can be conceptualized as existing along a spectrum that spans from pure unipolar depression with no intra- or inter-episode symptoms of (hypo)mania all the way to threshold level mania.

Figure 2 The probabilistic approach to differential diagnosis. Numerous factors, including early age at onset of first depressive episode, seasonality, antidepressant-induced (hypo)mania, and impulsivity, while not diagnostic of bipolar depression, are less common in pure unipolar depression compared to bipolar spectrum disorders. Moreover, the presence of psychotic features and extensive family history of psychopathology are additional probabilistic factors for BD. Patterns of comorbidity can also be evaluated as substance-use disorders, and several medical disorders (e.g., migraine and metabolic disturbances) are more common in BD when compared to MDD. Although the presence of any of these probabilistic qualities is not pathognomic, accumulation of these factors should alert clinicians to the possibility that their patient may lie along the bipolar spectrum, either with mixed depression or with bipolar depression.

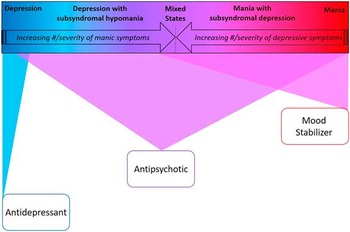

Figure 3 Bipolar spectrum-based first-line monotherapy treatment recommendations.

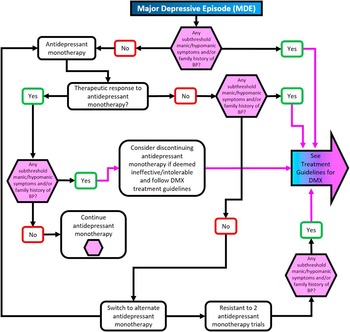

Figure 4 Treatment algorithm for major depressive episode without mixed features.

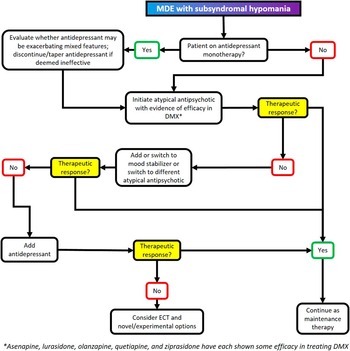

Figure 5 Treatment algorithm for major depressive episode with mixed features (DMX).

Figure 6 Relative tolerability of atypical antipsychotics.

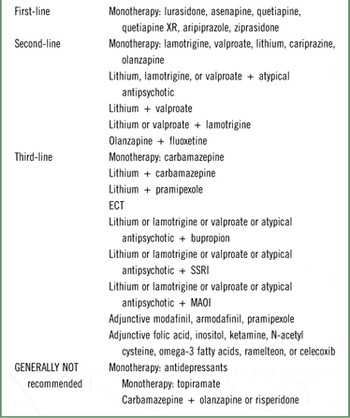

Table 1 Recommendations for acute pharmacological treatment of mixed depression a

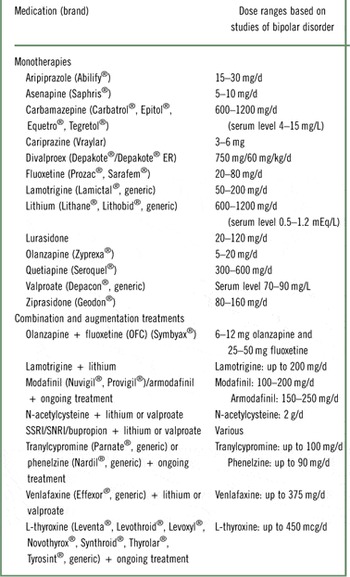

Table 2 Dosing recommendations for pharmacotherapy of mixed depression

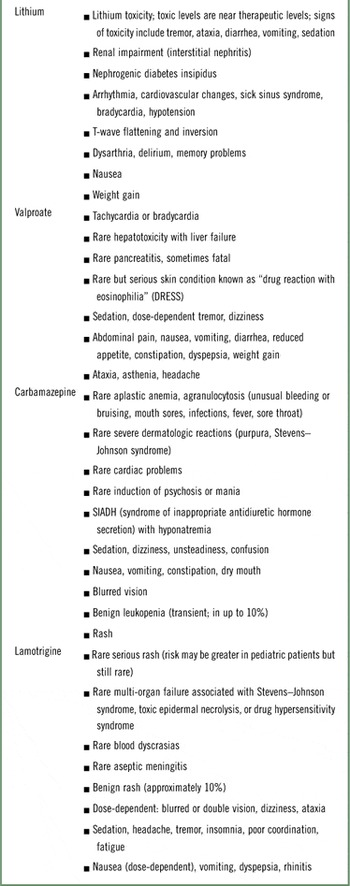

Table 3 Notable side effects associated with mood stabilizers

Table 4 Longitudinal monitoring according to treatment