Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the leading cause of disability worldwide, 1 with an estimated global point prevalence of 4.7% and a 12-month prevalence of 3.7%.Reference Ferrari, Somerville and Baxter 2 In the United States in 2017, 7.1% of all adults had at least one major depressive episode, 3 and in Canada, 11.3% of adults had a major depressive episode over their lifetime, with a 12-month prevalence rate of 4.7%.Reference Pearson, Janz and Ali 4

Patients with MDD have high rates of comorbidity with other mental conditions, such as anxiety disorders or substance abuse,Reference Kessler, Berglund and Demler 5 and an increased risk of depression or depressive symptoms is reported in patients with general medical conditions including asthma,Reference Ettinger, Reed and Cramer 6 diabetes,Reference Anderson, Freedland, Clouse and Lustman 7 -Reference Khaledi, Haghighatdoost, Feizi and Aminorroaya 9 cardiovascular disease,Reference Halaris 10 epilepsy,Reference Ettinger, Reed and Cramer 6 and chronic pain.Reference Bair, Robinson, Katon and Kroenke 11 , Reference Arnow, Hunkeler and Blasey 12 Together with MDD, chronic pain conditions are associated with the greatest number of disability days per year at the population level among a wide range of mental and chronic physical conditions.Reference Merikangas, Ames and Cui 13 The most recent prevalence estimate of chronic pain in Canada is 18.9%,Reference Schopflocher, Taenzer and Jovey 14 while estimates from the United States suggest nearly 2 out of 3 patients with depression also have chronic pain.Reference Arnow, Hunkeler and Blasey 12

In 2017, the 3 leading causes of years lived with disability worldwide were low back pain, headache disorders, and depressive disorder. 15 The estimated total annual cost of chronic pain in adults in the United States, including both direct healthcare costs and cost of lower worker productivity, is at least $560 billion.Reference Gaskin and Richard 16 In Canada, total annual healthcare spending for chronic pain management (direct costs only) was estimated to be $7.2 billion ($CAD).Reference Hogan, Taddio, Katz, Shah and Krahn 17 Depression with comorbid pain has been associated with increased economic burden through both increased costs and work disability.Reference Greenberg, Leong, Birnbaum and Robinson 18 In a questionnaire given to patients (n = 1204) attending a specialty pain clinic in the United Kingdom, patients with depression reported significantly more visits to their general practitioner and increased likelihood of seeking care from other doctors, using emergency room services, and being admitted to the hospital, compared with patients with pain who did not have depression.Reference Rayner, Hotopf, Petkova, Matcham, Simpson and McCracken 19

The management of depression in patients with chronic pain can be challenging due to common mechanisms and physiological associations between conditions, which may raise concerns among clinicians about prescribing medications for both conditions simultaneously. Using multiple drugs increases the risk of drug–drug interactions or additional risk for common adverse effects, particularly in patients with MDD who already have a high likelihood of polypharmacy.Reference Glezer, Byatt, Cook and Rothschild 20 -Reference Moore, Pollack and Butkerait 22 The Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) guidelines outline evidence-based recommendations for the management of MDD,Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 , Reference Lam, McIntosh and Wang 23 , Reference Parikh, Quilty and Ravitz 24 including antidepressant medication selection and a treatment optimization algorithm.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 Recommendations for the management of mood disorders in patients with psychiatric and medical comorbidities, including comorbid anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, substance use disorders, and medical disorders such as cardiovascular disease and multiple sclerosis, are addressed in a separate set of CANMAT reviews.Reference McIntyre, Alsuwaidan and Goldstein 25 -Reference Beaulieu, Saury and Sareen 29 However, management of patients with MDD and comorbid chronic pain has yet to be specifically addressed.

A collaboration was therefore undertaken to consider guidelines for the management of chronic pain together with the CANMAT Guidelines for Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder,Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 , Reference Lam, McIntosh and Wang 23 in order to develop recommendations for the treatment of MDD in patients with comorbid chronic pain. The International Classification of Diseases of the World Health Organization defines chronic pain as pain lasting or recurring for more than 3 months.Reference Treede, Rief and Barke 30 It comprises painful conditions that differ in their etiology and pathophysiology, including, but not limited to: chronic cancer pain arising from the cancer or the cancer treatment; chronic neuropathic pain, caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system; chronic musculoskeletal pain, arising as disease of the bone, joint, muscle, or related soft tissue; chronic visceral pain, originating from the internal organs (which can be perceived as referred pain in skin or muscle tissue); chronic headache and orofacial pain; and chronic primary pain, which includes conditions such as low back pain that is not found to be musculoskeletal or neuropathic in origin.Reference Treede, Rief and Barke 30 Because these chronic pain types are managed differently, we examined multiple guidelines addressing different types of chronic pain, including the 2017 Guideline for Opioid Therapy and Chronic Non-Cancer Pain,Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 the revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society,Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 the American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline for Low Back PainReference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 and the Guideline for the Evidence-Informed Primary Care Management of Low Back Pain. 34

The author group participated in multiple discussions, via email, telephone and videoconference, to reach consensus on treatment recommendations for this patient population. No formal process was used, and the result is a consensus of expert opinion that should be considered in conjunction with treatment guidelines. The aims of this article are to outline links between depression and pain in their occurrence, pathophysiology, and functional effects, and to provide clinical guidance, based on published evidence, on early and optimal pharmacological treatment for patients with MDD and comorbid chronic pain. Our goal is to provide a practical guide to help physicians treat this patient population based on the understanding that connections exist between depression and pain, both in terms of patient experience and potential treatment options.

Links between depression and chronic pain

Depression and chronic pain are intimately linked in a bidirectional relationship. Patients with chronic pain are at increased risk for mood disturbances including depression,Reference Turk, Audette, Levy, Mackey and Stanos 35 , Reference Radat, Margot-Duclot and Attal 36 and individuals with depression are more likely to experience painful conditions compared with those without mood symptoms.Reference Gupta, Silman and Ray 37 -Reference de Heer, Gerrits and Beekman 39 Predictors of depression in patients with chronic pain include more severe pain, greater number of pain sites, pain day and night, lack of identifiable cause of pain, and poor pain control.Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg 40 , Reference Ho, Li, Ng, Tsui and Ng 41

Estimates of comorbidity for chronic pain and MDD vary widely, depending on measures used to define both pain and depression. In a comprehensive review of studies published from 1966 to 2002, MDD was present in 2% to 100% of patients with chronic pain (or pain more than 6 months in duration), with a mean rate of 52%.Reference Bair, Robinson, Katon and Kroenke 11 In the same study, rates of pain in patients with MDD ranged from 15% to 100%, with a mean of 65%. In several more recent studies, chronic pain was reported in approximately 45% to 65% of patients with MDD.Reference Arnow, Hunkeler and Blasey 12 , Reference de Heer, Gerrits and Beekman 39 , Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg 40 , Reference Demyttenaere, Reed and Quail 42

Comorbid chronic pain in patients with MDD has negative impacts on both depression and pain outcomes. Patients with chronic pain and depression are more likely to have greater severity and longer duration of pain, and patients with higher pain scores experience longer time to response and remission of depression compared with patients with lower pain scores.Reference Leuchter, Husain and Cook 43 Increasing levels of pain severity are associated with progressively decreasing likelihood of improvement in depression overall.Reference Leuchter, Husain and Cook 43

Common neurophysiology in depression and pain

Although the exact cause of the links between depression and pain are unknown, several possible mechanisms for their association have been posited. First, pain and depression are both known to affect several anatomic brain regions that are involved in emotional processing,Reference Torta, Pennazio and Ieraci 44 including the anterior cingulate cortex, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala, and thalamus.Reference Doan, Manders and Wang 45 -Reference Fasick, Spengler, Samankan, Nader and Ignatowski 47 Pain and depression also share serotonergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic neurotransmitter pathways arising primarily from limbic structures that are associated with emotional processing.Reference Doan, Manders and Wang 45 , Reference Li and Peng 46 , Reference Chopra and Arora 48 -Reference Han and Pae 50 Neuromodulation of pain via descending efferent pathways may also be impaired in depression, as a negative emotional state increases the perceived unpleasantness of pain via anterior cingulate cortex—PFC—periaqueductal gray circuitry,Reference Bushnell, Ceko and Low 51 and cognitive variables such as pessimism and catastrophizing has been found to magnify pain-related stimuli.Reference Han and Pae 50 , Reference Edwards, Cahalan, Mensing, Smith and Haythornthwaite 52 Some antidepressants that target serotonergic, dopaminergic, or noradrenergic pathways for the treatment of depression have also demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of pain,Reference Doan, Manders and Wang 45 , Reference Chopra and Arora 48 -Reference Han and Pae 50 providing further evidence of shared mechanisms between depression and pain.Reference Chopra and Arora 48 , Reference Shah and Moradimehr 53

Central and peripheral neuroinflammation have been associated with pain and depression in preclinical studies.Reference Pryce, Fontana, Dantzer and Capuron 54 , Reference Walker, Kavelaars, Heijnen and Dantzer 55 Increases in pro-inflammatory biomarker levels have been linked to both depression and pain,Reference Han and Pae 50 , Reference Burke, Finn and Roche 56 and evidence of chronic and sustained neuroinflammation has been observed in brain areas associated with mood and pain.Reference Burke, Finn and Roche 56 It is notable that some antidepressant medications have anti-inflammatory effects,Reference Burke, Finn and Roche 56 and that some patients with treatment-resistant depression have shown improvements in depression-related outcomes when treated with monoclonal antibodies to the inflammatory mediator anti-tumor necrosis factor-α.Reference Raison, Rutherford and Woolwine 57

Sleep and fatigue symptoms form an additional link between pain and depression. Sleep disturbances or fatigue caused by depression or by medications used to treat it may increase pain directly by disrupting reparative or restorative functions or heightening pain experience indirectly by impairing adaptive mechanisms.Reference Call-Schmidt and Richardson 58 Conversely, the use of opiates for pain can cause insomniaReference Fuggle, Curtis and Shaw 59 and sleep disordered breathing,Reference Cao and Javaheri 60 which might worsen the course of depression or cause symptomatic overlap. Again, the exact underlying cause of this association is not known, but there may be a shared pathophysiology linking sleep symptoms to those of pain and depression. It has been suggested that insomnia, chronic pain, and depression may have a common underlying dysfunction in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system.Reference Finan and Smith 61 Other neurological substrates common to insomnia, depression, and chronic pain include stress/Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) activity, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), proinflammatory cytokines, and serotonin.Reference Boakye, Olechowski and Rashiq 62 Chronic pain and depression have been conceptualized as overlapping central sensitivity syndromes linked with sleep and fatigue,Reference Kato, Sullivan, Evengard and Pedersen 63 -Reference Kato, Sullivan, Evengard and Pedersen 65 and sleep and pain have been construed as competing neurological states.Reference Call-Schmidt and Richardson 58 Insomnia is a potential activating influence between chronic pain and suicide.Reference Cheatle 66 Therefore, screening for and treating insomnia and sleep disordered breathing are warranted, using caution to avoid nonspecific over-sedation in chronic pain patients. Nonpharmacological treatments can improve sleep in patients with painReference Papaconstantinou, Cancelliere and Verville 67 and should always be considered before medication. However, sleep and fatigue symptoms may also improve with aggressive treatment of pain and depression.

Potentiation of depression and pain

Results of studies on patients with pain and/or depression show that these conditions can each intensify the experienced symptoms of the other. A systematic review of 16 studies examining mental health risk factors for knee pain demonstrated a strong association between knee pain and depression,Reference Phyomaung, Dubowitz and Cicuttini 68 with an increased severity of pain associated with an increased likelihood of depression.Reference Phyomaung, Dubowitz and Cicuttini 68 Ongoing pain can worsen depressive symptoms,Reference Torta, Pennazio and Ieraci 44 as well as intensify the loss of function and reduced quality of life associated with depression.Reference Arnow, Hunkeler and Blasey 12 , Reference Leuchter, Husain and Cook 43

Evidence also indicates that depression can amplify pain perceptionReference Torta, Pennazio and Ieraci 44 and exacerbate impairment caused by pain.Reference Jain, Jain, Raison and Maletic 69 For example, in one study, a significantly larger proportion of patients with MDD rated chronic pain as being severe or unbearable compared with nondepressed individuals (65% vs 43%, respectively; P < .001).Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg 40 Patients with MDD also report higher frequency of pain and a higher number of pain sites than nondepressed individuals with chronic pain.Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg 40 Depression is believed to reduce pain thresholds and increase pain perception,Reference Torta, Pennazio and Ieraci 44 especially in neuropathic pain, which can be worsened or magnified with coexisting depression or anxiety.Reference Jain, Jain, Raison and Maletic 69

Pharmacotherapy for depression with comorbid pain

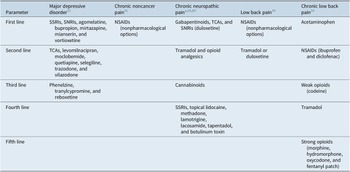

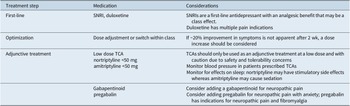

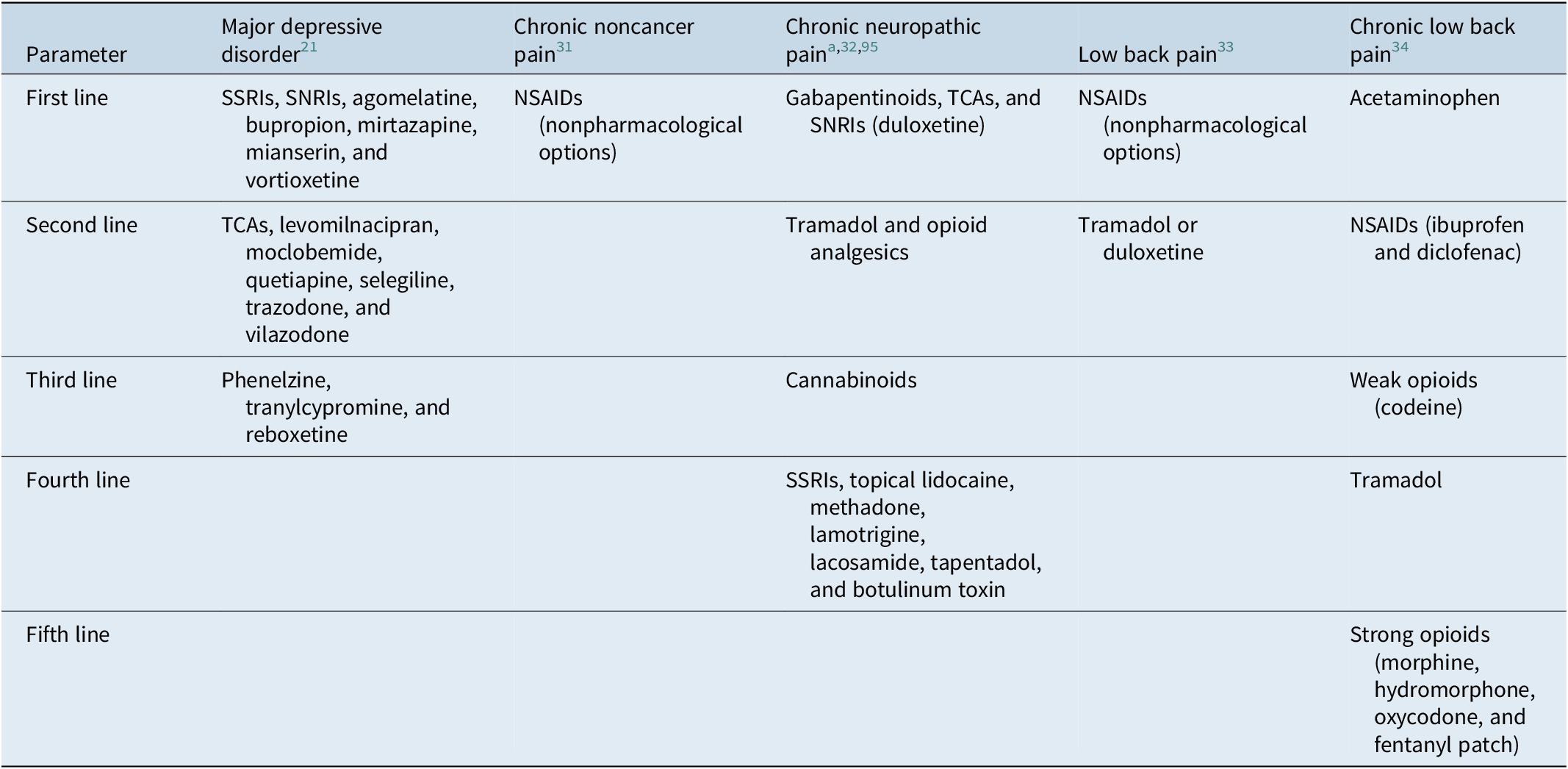

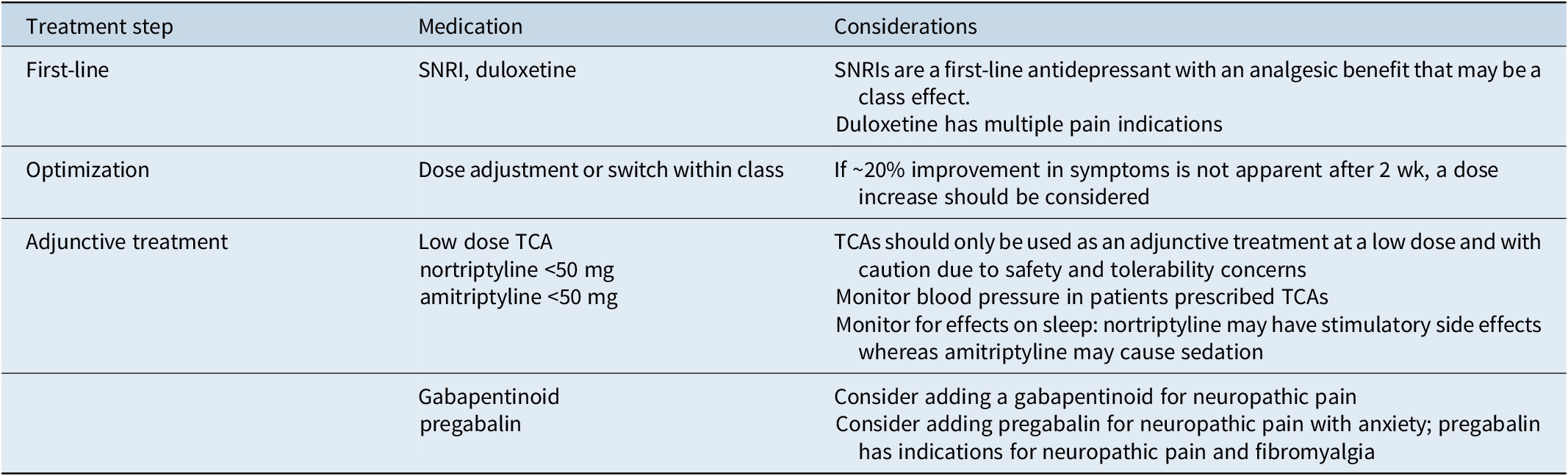

Rapid diagnosis and early optimization of treatment are critical for providing the best possible outcomes for individual patients with MDD.Reference Habert, Katzman and Oluboka 70 , Reference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71 Delaying effective treatment of major depression can have negative impacts on patients’ brain structure and functionReference Moylan, Maes, Wray and Berk 72 and reduce the likelihood of achieving remission with antidepressant treatment.Reference Okuda, Suzuki and Kishi 73 -Reference Ghio, Gotelli, Marcenaro, Amore and Natta 75 Because improvement in depression alone often reduces pain symptoms, the imperative for patients with MDD and comorbid pain is to focus on aggressive treatment of depression, while managing pain with first-line pain medication such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; Table 1).Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 , Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 After optimizing MDD treatment, the clinician can determine whether concomitant analgesic medication is needed and if so, whether a change to that medication is required. Here, we summarize recommendations for early optimized treatment of depressive symptoms and functional impairment in MDD (published previously in detailReference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71), and consider pros and cons of pain medication options for patients with MDD, should they be needed in addition to the treatment used for management of depression. Our recommendations for managing pharmacotherapy in patients with MDD and pain are provided in Table 2. For patients with depression who are already prescribed medication for chronic pain, a treatment plan should be developed in consultation with the pain care provider.

Table 1. Recommended Medications for Depression and Pain Based on Treatment Guidelines.

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine inhibitor; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

a Consider adding additional agents sequentially if partial or inadequate pain relief.

Table 2. Recommendations for Pharmacotherapy in Patients with Depression and Chronic Pain. a

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SNRI, serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

a NSAIDs are recommended for pain while treatment for depression is optimized.

Measurement based care: screening and assessment

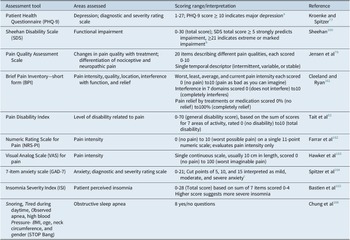

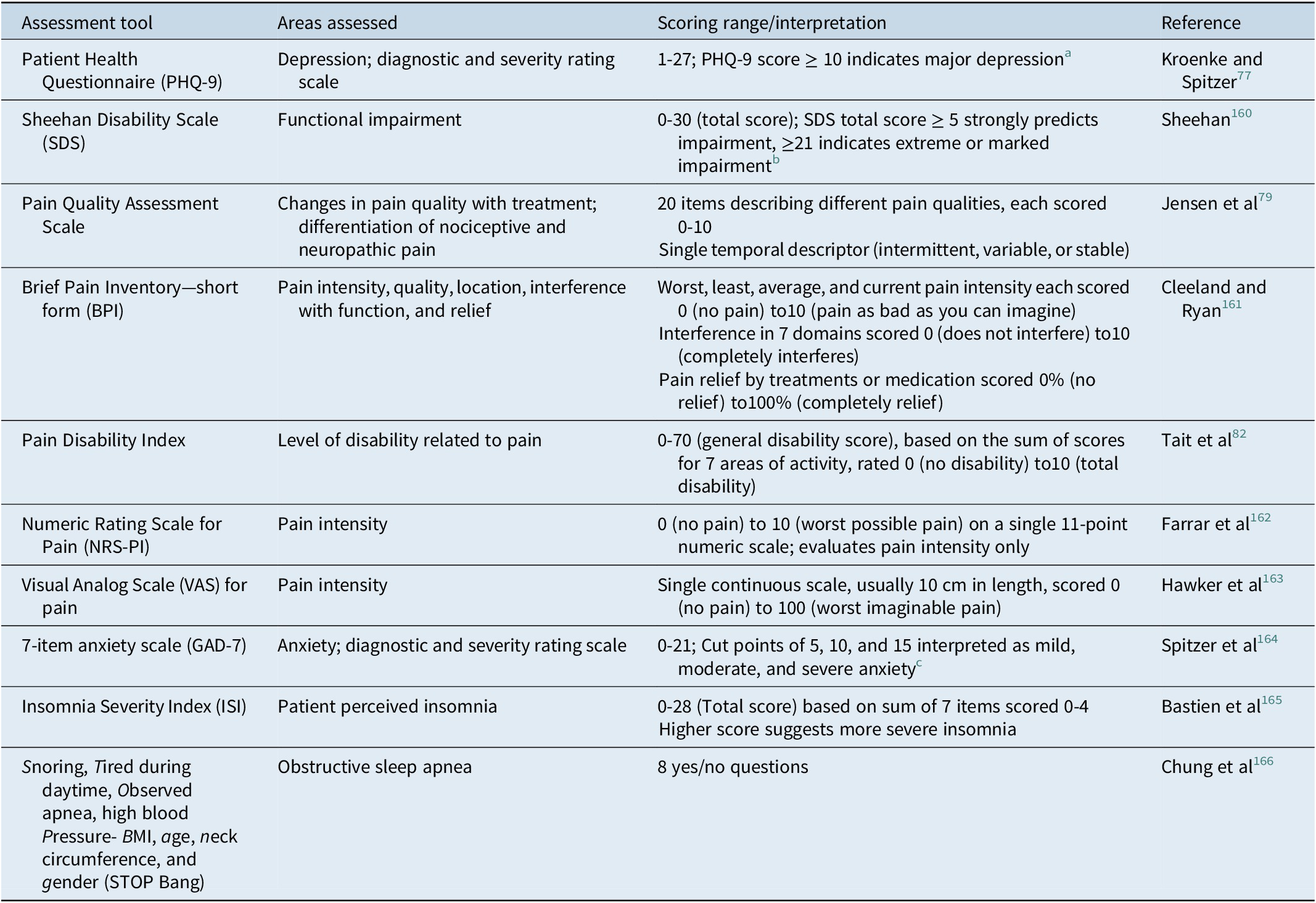

Screening for depression in patients with pain can reduce the duration of untreated illness in those not primarily reporting mood symptoms. Screening may be of particular importance for patients with chronic pain and/or sleep disturbance, as patients with depression may actually be more likely to report somatic pain and sleep problems than depression itself.Reference Ohayon and Schatzberg 40 Table 3 provides examples of tools for screening for depression and pain, as well as sleep disturbance and anxiety, which are likely to co-occur with depression.Reference Kessler, Berglund and Demler 5 , Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 These same assessments can, and should, be administered regularly during treatment to monitor for improvement in symptoms and function, as previously described in detail.Reference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71 The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) 76 can be used to screen for and diagnose depression; a PHQ-9 score of 5 is the threshold for mild depression; a score of ≥10, which has a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depression, is recommended as a screening cut point for moderate/severe MDD.Reference Kroenke and Spitzer 77 The PHQ-9 and a function scale such the Sheehan Disability ScaleReference Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan and Raj 78 can also be used for assessing severity of symptoms and functional impairment, respectively, to inform the treatment plan and monitor early improvement. Several pain scales are useful for initial assessment and monitoring during treatment: the Pain Quality Assessment Scale differentiates nociceptive from neuropathic pain on screening,Reference Jensen, Gammaitoni, Olaleye, Oleka, Nalamachu and Galer 79 , Reference Breivik, Borchgrevink and Allen 80 the Brief Pain Inventory—short form 81 measures pain severity and degree of interference with function.Reference Breivik, Borchgrevink and Allen 80 The Pain Disability Index assesses the level of impairment in a range of functional domains.Reference Tait, Pollard, Margolis, Duckro and Krause 82 - 84

Table 3. Assessment Tools for Measurement-Based Care in Patients with Depression and Pain.

a PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 had a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 88% for major depression.Reference Kroenke and Spitzer 77

b Based on SheehanReference Sheehan, Rush, Pincus and First 160 and Sheehan and Sheehan.Reference Sheehan and Sheehan 167

c Based on Spitzer.Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Lowe 164

Pharmacotherapy for MDD

First line treatments for MDD include most second-generation antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRIs], agomelatine, bupropion, mirtazapine, and vortioxetine; Table 1)Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21; more recent head-to-head trials and network meta-analyses indicate that levomilnacipran and vilazodone also have similar efficacy to these second-generation antidepressants.Reference Wagner, Schultes, Titscher, Teufer, Klerings and Gartlehner 85 Based on CANMAT guidelines and our clinical experience, our recommendation is to initiate treatment with an SNRI such as duloxetine or venlafaxine for patients with comorbid pain.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 In systematic reviews, duloxetine has demonstrated efficacy for treating multiple chronic pain conditions, including neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and painful physical symptoms in depression.Reference Hauser, Urrutia, Tort, Uceyler and Walitt 86 , Reference Lunn, Hughes and Wiffen 87 Venlafaxine significantly improved pain vs placebo in clinical trials of painful diabetic neuropathy.Reference Kadiroglu, Sit, Kayabasi, Tuzcu, Tasdemir and Yilmaz 88 , Reference Rowbotham, Goli, Kunz and Lei 89 It could be presumed that this analgesic benefit may be a class effect of SNRIs.

Early and ongoing monitoring of depression symptoms and function, treatment adherence, and tolerability is critical for making adjustments to treatment when an adequate trial does not yield clinically significant improvement.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 , Reference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71 Approximately 20% improvement in symptoms is expected after 2 to 4 weeks of treatmentReference Habert, Katzman and Oluboka 70; if early improvement is not apparent after 2 weeks, a dose increase should be considered.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 , Reference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71 If symptoms are still not improving after dose optimization, an adjunctive treatment or a switch to another monotherapy in the same or different antidepressant class may be needed.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 , Reference Oluboka, Katzman and Habert 71

The CANMAT guideline recommends atypical antipsychotic drugs such as aripiprazole as first-line adjunctive treatment for nonresponse or partial response to an antidepressant monotherapy for symptoms of MDD.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21 If trials of 2 different SNRIs fail, adding a low-dose tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), such as amitriptyline, nortriptyline, or desipramine should also be considered for patients with MDD and pain. TCAs have a poor safety and tolerability profile at standard doses for treating MDD (≥100 mg/d), but may have similar efficacy for treating depression at lower doses,Reference Furukawa, McGuire and Barbui 90 and several TCAs have also demonstrated efficacy for treating painful conditions.Reference McCleane 91 -Reference Uhl, Roberts, Papaliodis, Mulligan and Dubin 94 Nonetheless, due to their high side effects burden, TCAs are not recommended as a first-line treatment and they should only be used as an adjunctive treatment with caution.Reference Kennedy, Lam and McIntyre 21

Pharmacotherapy for chronic pain in patients with MDD

After depressive symptoms have been stabilized and function has improved, the clinician can assess whether additional treatment for pain is required. Possible benefits and harms of available options should be considered for each individual patient. Published guidelines for the treatment of chronic pain focus on different pain conditions, including chronic noncancer pain,Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 chronic neuropathic pain,Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 , Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95 and low back pain.Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 Consequently, recommendations for pain pharmacotherapies differ among the various organizations that provide them (Table 1). It is important to note that nonpharmacological therapies are considered first-line options or essential to the enhancement of pharmacotherapy in all of those guidelines. Guideline recommendations for nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain include exercise therapy, physiotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy-based psychological treatment, mindfulness-based stress reduction, acupuncture, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation.Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 -Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In guidelines from the National Opioid Use Guideline GroupReference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 and the American College of Physicians,Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 NSAIDs are recommended as first-line pharmacotherapy for chronic noncancer pain and low back pain.Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 , Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 Clinical trial evidence suggests that there is a small to moderate effect of NSAIDs on reducing low back pain.Reference Chou, Deyo and Friedly 96 A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing NSAID therapy vs opioids showed no difference in pain control (9 trials) or functioning (7 trials) for the 2 therapies in patients with chronic noncancer pain, with a significant risk for opioid treatment over NSAIDs.Reference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin 97 Ibuprofen may be more effective than acetaminophen in acute pain conditions, but there are limited data comparing these for chronic pain.Reference Moore, Derry, Wiffen, Straube and Aldington 98 NSAIDs have not demonstrated efficacy vs placebo in patients with neuropathic pain,Reference Moore, Chi, Wiffen, Derry and Rice 99 and the Canadian Pain Society does not recommended for that condition.Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32

Clinicians should counsel patients with contraindications for NSAIDs. Gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney damage, and increased cardiac adverse events have been associated with NSAID use, and these medications are potentially hazardous for elderly patients, who are at particular risk for these conditions.Reference Modig and Elmstahl 100 Bleeding risk is additive when other medications associated with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, such as selective SSRIs, are taken concurrently with NSAIDs.Reference Anglin, Yuan, Moayyedi, Tse, Armstrong and Leontiadis 101 , Reference Jiang, Chen and Hu 102 Due to GI bleeding and renal risks, American College of Physicians guidelines for low back pain recommend that when NSAIDs are used, the lowest effective doses should be taken for the shortest periods necessary.Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding may be reduced using acid-suppressing drugs concurrently.Reference Jiang, Chen and Hu 102

Antidepressant medications

The Canadian Pain Society recommends TCAs, SNRIs, and gabapentinoids as first-line therapy for neuropathic painReference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95; the SNRI duloxetine is a second-line recommendation from the American College of Physicians for low back pain.Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 TCAs, including amitriptyline, have confirmed efficacy in various neuropathic pain conditions (number needed to treat [NNT] for a 50% pain reduction ≈ 4).Reference Attal 103 , Reference Saarto and Wiffen 104 In clinical practice, amitriptyline is used at low doses for management of neuropathic pain (5-10 mg/d for >70% of 281 doctors surveyed)Reference Kamble, Motlekar, D’Souza, Kudrigikar and Rao 105 due to its poor tolerability profile at higher doses.Reference Guaiana, Barbui and Hotopf 106 , 107 Several studies support the use of nortriptyline for neuropathic pain, although most of those are also limited by small study size.Reference Derry, Wiffen, Aldington and Moore 108 TCAs in general have a very high burden of side effects, including somnolence, anticholinergic effects, weight gain,Reference Attal 103 and possible cardiac conduction block and orthostatic hypotension.Reference Gilron, Baron and Jensen 109 Before prescribing a TCA, patient symptoms and possible effect on sleep should be carefully considered. If the patient presents with significant insomnia, it may be beneficial to initiate treatment with a TCA with hypnotic effects, such as amitriptyline, doxepin, or trimipramine.Reference Wichniak, Wierzbicka, Walecka and Jernajczyk 110 However, the ratio of next day sedation to pain control and overall functional improvement needs to be kept in mind.

SNRIs such as duloxetine and venlafaxine have demonstrated efficacy in neuropathic pain with a NNT for a 50% reduction in neuropathic pain of 6.4 for duloxetineReference Attal 103 and 3.1 for venlafaxine.Reference Saarto and Wiffen 111 Duloxetine has also demonstrated efficacy vs placebo for treating painful diabetic neuropathy (duloxetine 60 mg, NNT = 5), fibromyalgia (NNT = 8), and painful physical symptoms in depression (NNT = 8) in a Cochrane Review.Reference Lunn, Hughes and Wiffen 87 In an indirect meta-analysis, no difference in efficacy was observed between duloxetine and SSRIs, Cox-2 inhibitors, glucosamine, or nonscheduled opioids.Reference Cawston, Davie, Paget, Skljarevski and Happich 112 Desvenlafaxine treatment significantly reduced pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in a single study, at high doses only (200 and 400 mg/d).Reference Allen, Sharma and Barlas 113 Some SNRIs may be associated with weight gain or sexual dysfunction, both of which may reduce adherence to treatment.Reference Wise, Perahia, Pangallo, Losin and Wiltse 114 - 117 Other possible adverse events include nausea, abdominal pain, constipation, hypertension (dose related with venlafaxineReference Attal 103), loss of appetite, sedation, dry mouth, hyperhidrosis, and anxietyReference Gilron, Baron and Jensen 109; these effects can vary from agent to agent within the SNRI class.Reference Stahl, Grady, Moret and Briley 118 Patients should also be monitored for suicidal thoughts or behavior, as treatment with TCAs, SNRIs, and other antidepressant medications are also associated with an increased risk for suicidal behavior.Reference Simon, Savarino, Operskalski and Wang 119

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentinoids are used for neuropathic pain with U.S. indications for fibromyalgia, postherpetic neuralgia, and neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy or spinal cord injury; pregabalin, but not gabapentin, has indications for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in Canada. 120 - 123 Pregabalin also has demonstrated efficacy vs placebo for treating anxiety in clinical trials; clinical response was comparable for pregabalin and benzodiazepines in a meta-analysis.Reference Generoso, Trevizol, Kasper, Cho, Cordeiro and Shiozawa 124 The NNT to achieve 50% pain relief with gabapentin is 6.3 to 8.3; for pregabalin, the NNT is 5.6 to 7.7 in neuropathic pain.Reference Attal 103 , Reference Wiffen, Derry and Moore 125 The safety profile of gabapentinoids includes risk of sedation, dizziness, peripheral edema, weight gain,Reference Attal 103 and blurred vision.Reference Gilron, Baron and Jensen 109 Effects on cognition, including disturbance in attention, abnormal thinking, and confusion, are also reported for pregabalin.Reference Zaccara, Gangemi, Perucca and Specchio 126

Opioid analgesics

Tramadol is recommended as a second-line medication in guidelines for both low back painReference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 and chronic neuropathic painReference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 , Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95; the guideline for chronic neuropathic pain includes other opioid analgesics in that recommendation as well.Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 , Reference Qaseem, Wilt, McLean and Forciea 33 , Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95 However, caution is warranted when using tramadol with serotonergic drugs such as SSRIs,Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 , Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95 and the 2017 Canadian Guideline for Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain includes a strong recommendation for optimization of nonopioid pharmacotherapy and nonpharmacologic therapy rather than a trial of opioids for patients with chronic, noncancer pain.Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 For chronic pain patients with a comorbid psychiatric disorder, the 2017 guideline recommends stabilization of the psychiatric disorder before a trial of opioids is considered; opioid therapy is not recommended for patients with chronic noncancer pain and a history of substance use disorder.Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 The reported NNT for 50% neuropathic pain relief is 4.7 for tramadol.Reference Attal 103 However, a recent meta-analysis of 96 randomized controlled trials for chronic noncancer pain found that opioids provided only small advantages vs placebo, possibly due to the development of opioid tolerance or opioid-induced hyperalgesia.Reference Busse, Wang and Kamaleldin 97

Opioid analgesics are associated with nausea, vomiting, constipation, dizziness, somnolence, and the potential for abuse and addiction.Reference Attal 103 , Reference Els, Jackson and Kunyk 127 Up to a quarter of all U.S. patients on long-term opioid therapy may develop dependence and addiction.Reference Kaye, Jones and Kaye 128 The prevalence of opioid use disorder in people who received chronic opioid therapy may be up to 20% to 25% or more.Reference Kaye, Jones and Kaye 128 -Reference Banta-Green, Merrill, Doyle, Boudreau and Calsyn 131 Tramadol (like the structurally related tapentadol) is a partial μ opioid receptor agonist with an upper bound on analgesic activity, but it also has central GABA, catecholamine, serotonergic, and noradrenergic activities, which may reduce its abuse potential compared with full antagonists such as morphine, hydromorphone, and fentanyl.Reference Trescot, Datta, Lee and Hansen 132 -Reference Butler, McNaughton and Black 135 Nonetheless, abuse of tramadol and tapentadol remains a risk, particularly with oral administration.Reference Epstein, Preston and Jasinski 134 Most critically, however, opioids can double the risk of depression recurrence potentially in a dose-dependent manner.Reference Scherrer, Salas and Copeland 136 , Reference Mazereeuw, Sullivan and Juurlink 137

In accordance with the guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain, nonopioid treatment options should be considered over opioid analgesics because of abuse potential, the significantly increased risk of serious adverse events, and the increased risk of depression recurrence.Reference Busse, Craigie and Juurlink 31 , Reference Els, Jackson and Kunyk 127 , Reference Scherrer, Salas and Copeland 136 Although a partial agonist such as tramadol may have a lower (but not negligible) potential for abuse and for respiratory depression,Reference Trescot, Datta, Lee and Hansen 132 -Reference Butler, McNaughton and Black 135 tramadol can result in drug–drug interactions with an increased risk for serotonergic syndrome in patients also prescribed SSRIs or SNRIs.Reference Spies, Pot, Willems, Bos and Kramers 138

Emerging therapies

The Canadian Pain Society currently recommends cannabinoids as third-line agents for neuropathic pain due to a lack of evidence from high quality trials supporting their efficacy.Reference Moulin, Boulanger and Clark 32 , Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95 Despite evidence of moderate improvement in neuropathic pain with cannabinoid treatment, the NNT for benefit was high (24) and the NNT for harm was low (6) in a recent meta-analysis.Reference Stockings, Campbell and Hall 139 Selective cannabinoids demonstrated a small but statistically significant analgesic effect as an adjunct treatment for neuropathic pain in a second meta-analysis.Reference Meng, Johnston, Englesakis, Moulin and Bhatia 140 Based on a more recent review of the evidence, the International Association for the Study of Pain released a position statement that did not endorse the use of cannabinoids for the treatment of pain, due to lack of high-quality clinical evidence. 141 The value of these therapies in pain is uncertain, with little or no evidence in patients with depression.Reference Whiting, Wolff and Deshpande 142

Other potential therapies worth future consideration include anti-inflammatory drugs with antidepressant effects, such as infliximab.Reference Matsuda, Huh and Ji 143 , Reference Bekhbat, Chu and Le 144 Ketamine, which was originally developed as an anesthetic and has short-term analgesic effects, may be of particular interest as a future therapy, as it has emerged as a treatment for treatment-resistant depression, with evidence supporting its use in MDD.Reference Peltoniemi, Hagelberg, Olkkola and Saari 145 -Reference Wan, Levitch and Perez 148 Long-term analgesic effects of ketamine have not yet been rigorously examined.Reference Peltoniemi, Hagelberg, Olkkola and Saari 145

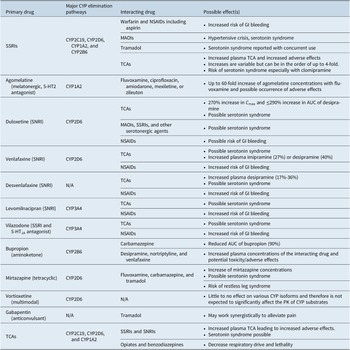

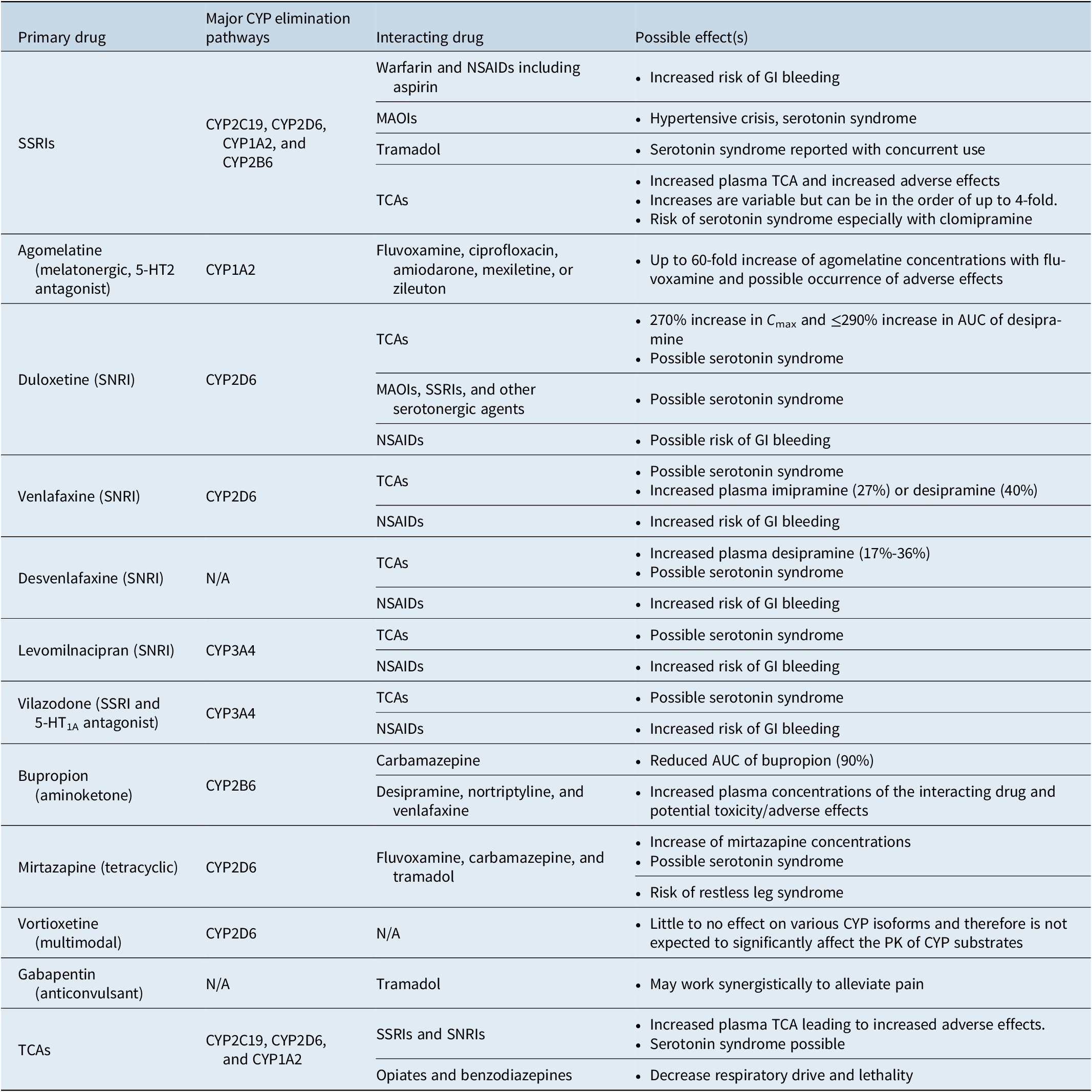

If the approach to the treatment of comorbid MDD with chronic pain involves the use of multiple medications, the potential for drug–drug interactions must be considered (Table 4).Reference Manolopoulos, Ragia and Alevizopoulos 149 -Reference Nichols, Abell, Chen, Behrle, Frick and Paul 155 Many medications used in the treatment of MDD are metabolized via the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme system and can inhibit or induce the activity of those enzymes.Reference Preskorn, Shah, Neff, Golbeck and Choi 156 Such drug interactions alter plasma drug concentrations, which can result in reduced efficacy and/or increased adverse effects.Reference Preskorn, Shah, Neff, Golbeck and Choi 156 , Reference Preskorn and Werder 157 Careful appraisal of drug–drug interactions listed in drug labeling is essential for safely prescribing multiple drugs for the treatment of MDD and pain. Online resources, such as SwitchRx, 158 are also available to provide clinicians with current information on combined drug strategies for psychotropic medications.

Table 4. A Summary of Potential Drug–Drug Interactions Among Compounds Likely to be Used to Treat Concomitant MDD and Chronic Pain.Reference Manolopoulos, Ragia and Alevizopoulos 149 -Reference Nichols, Abell, Chen, Behrle, Frick and Paul 155

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CNS, central nervous system; CYP, cytochrome P450; GI, gastrointestinal; MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PK, pharmacokinetics; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Response to pain therapy may be best measured by monitoring patients’ sleep and functioning.Reference Mu, Weinberg, Moulin and Clarke 95 , Reference Polatin, Bevers and Gatchel 159 For patients who fail to achieve functional improvement with the pain management plan, consultation with a pain specialist or referral to multimodal pain clinic should be considered. In addition to regular assessment of improvement in both pain and depressive symptoms and function, monitoring for adverse side effects is essential, as tolerability will ultimately contribute to patient adherence and efficacy of the treatment.

Conclusions

The incidence of comorbid chronic pain is high in patients with depression, as pain and depression exacerbate symptoms and influence treatment outcomes in a bidirectional manner. In addition, the presence of comorbid pain in depression can complicate the diagnosis and management of both conditions. Early diagnosis, rapid optimization of treatment, and addressing residual symptoms are key to successful management of MDD. For patients with MDD who have chronic pain, we provide recommendations (Table 2) for aggressively managing depression, focusing on antidepressant medications with analgesic properties and addressing pain with first-line pharmacotherapy as treatment for depression is optimized, before considering additional drugs to address residual pain symptoms. Potential benefits and harms of pharmacotherapy options for treating pain should be carefully weighed for each individual patient. Careful consideration should be given to potential adverse effects and potential drug–drug interactions when multiple drugs are prescribed.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Kathleen Dorries, PhD, Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and was funded in part by Pfizer Canada ULC and in part by the authors. Authors are entirely responsible for the scientific content of the paper.

Author contributions

Data interpretation: all authors; Manuscript preparation: all authors; Manuscript review and revisions: all authors; Final approval of manuscript: all authors.

Disclosures

O.J.O.: Speakers bureau/honoraria: Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Janssen, Sunovion, Shire, Purdue, and Allergan; clinical trials: Otsuka/Lundbeck; M.A.K.: Ownership/partnership: START Clinic for Mood and Anxiety Disorders; employment: START Clinic for Mood and Anxiety Disorders, Adler Graduate Professional School, Northern Ontario School of Medicine (NOSM) (Laurentian and Lakehead University); advisory board (or similar committee): AbbVie Eisai, Empower Pharma, Jansen, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Sante Cannabis, Shire, Takeda, Tilray; clinical trials: Lundbeck; Honoraria or other fees (eg, travel support): Allergan, Jansen, Lundbeck Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Shire, Takeda, and Tilray; research grants: Pfizer; J.H.: Pfizer, Allergan, Amgen, Aralez, Astra-Zeneca, Bausch, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer, Eli-Lilly, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Purdue, Servier, Roche, and Otsuka; D.M. has received honoraria for ad hoc speaking or advising/consulting from Abbvie, Allergan, Bausch Health, BC Children’s and Women’s Hospital, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, Eisai, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, PsychedUp CME, Purdue, Save-On-Foods, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, Western University and the University of Ottawa. D.M. is the co-director of PsychedUp CME and Chief Neuroscience Officer at Telus Communications; A.K. has received honoraria /or is member of advisory board for Allergan, Bausch Health, Eisai, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Sunovion, Spectrum, Tilray, and Takeda; R.S.M. has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation; speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie. R.S.M. is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp; C.N.S. has received honoraria as a consultant for Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Sunovion and research grants from the AFP Innovation Fund, Ontario Research Fund, Canadian Menopause Society, and Ontario Brain Institute; M.A.O. has received honoraria /or is member of advisory board for Allergan, AbbVie, Eisai, Elvium, Janssen, Lundbeck Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, and Wyeth; R.W.L. has received honoraria for ad hoc speaking or advising/consulting, or received research funds, from Akili, Allergan, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, BC Leading Edge Foundation, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments, Canadian Psychiatric Association, CME Institute, Hansoh, Healthy Minds Canada, Janssen, Lundbeck, Lundbeck Institute, Medscape, MITACS, Movember Foundation, Ontario Brain Institute, Otsuka, Pfizer, St. Jude Medical, University Health Network Foundation, and VGH-UBCH Foundation; L.J.K. has received honoraria and/or is a member of advisory board for Allergan, CADDRA, Canadian Psychiatric Association, CINP, European Psychiatric Association, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Sunovion, Takeda, and Tilray; R.T.: Unrestricted conference grants from Allergan, Canopy, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Shire, and Sunovion; previous speaker honoraria from Allergan, Canopy, Indivior, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Pfizer; previous member of advisory boards for Allergan, Canopy, and Tilray; clinical trial funding from Sundial Growers and Olds SoftGels; research grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addiction Program, CAN Health Network, and Alberta Innovates; and speaker’s bureau/honoraria with Master Clinician Alliance. He was appointed to a government review committee, the Supervised Consumption Services Review Committee, for which he received renumeration for his time away from his workplace and reimbursement for travel, living, or other expenses reasonably incurred while away from his place of residence according to the Public Service Relocation and Employment Expenses Regulation and the Government of Alberta Travel Meal and Hospitality Expenses Directive.