No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

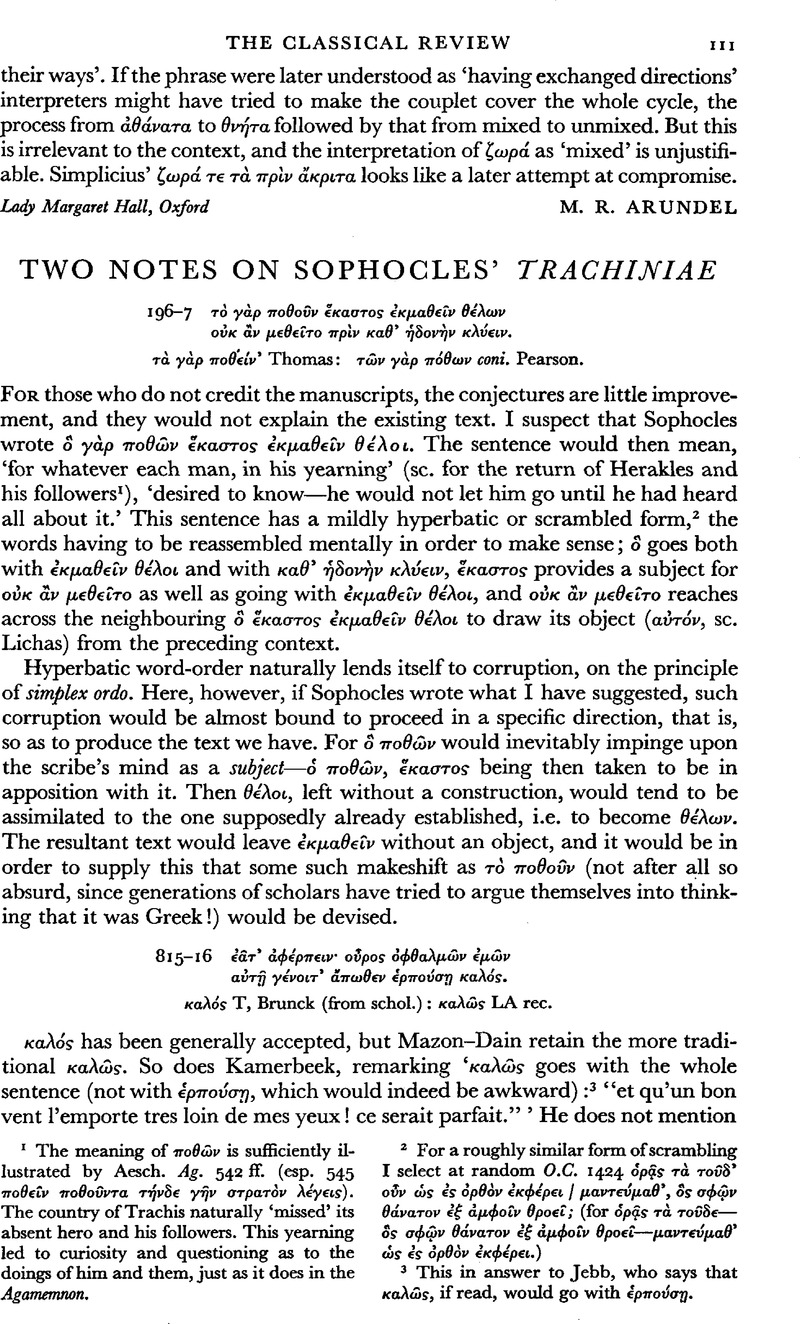

Two Notes on Sophocles' Trachiniae

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

page 111 note 1 The meaning of ποθ⋯ν is sufficiently illustrated by Aesch. Ag. 542 ff. (esp. 545 ποθεῖν ποθο⋯ντα τ⋯νδε γ⋯ν στρατ⋯ν γ⋯γεις). The country of Trachis naturally ‘missed’ its absent hero and his followers. This yearning led to curiosity and questioning as to the doings of him and them, just as it does in the Agamemnon.

page 111 note 2 For a roughly similar form of scrambling I select at random O.C. 1424 ⋯ρᾷς τ⋯ το⋯δ᾽ οὖν ὡς ⋯ς ⋯ρθ⋯ν ⋯κφ⋯ρει / μαντε⋯μαθ᾽, ο̂ς σφῷν θ⋯νατον ⋯ξ ⋯μφοῖν θροεῖ; (for ⋯ρᾷς τ⋯ το⋯δε—ο̂ σφῷν θ⋯νατον ⋯ξ ⋯μφοῖν θροεῖ—μαντε⋯μαθ᾽ ὡς ⋯ς ⋯ρθ⋯ν ⋯κφ⋯ρει.)

page 111 note 3 This in answer to Jebb, who says that καλ⋯ς, if read, would go with ⋯ρπο⋯σῃ.

page 112 note 1 Jebb makes the sensitive remark that the constructure of the sentence throws a particular emphasis on ⋯φθαλμ⋯ν ⋯μ⋯ν.

page 112 note 2 This example has exactly the same pedi-mental (or, better, anti-pedimental structure) as Tr. 815 f., with οὕτω χρ⋯νῳ τοσῷδ᾽ in the centre, το⋯δ᾽ ἄγαν ⋯πεστρ⋯φοντο divided between the two middle positions, and τ⋯νος πρ⋯γματος χ⋯ριν divided between the extremities. Jebb's note is extremely instructive. He says, ‘the order of words is remarkable, not only because τ⋯νος is so far from πρ⋯γματος, but also because it is closely followed by το⋯᾽, so that when the ear caught the first words, the sense expected might naturally be, “who was for this the man for whom”, etc.—The motive has been the wish to emphasise the pron., referring to Philoctetes.’ In spite of his sensitiveness to verbal effects he fails here, as so often, to perceive the true structure of the sentence, and, in doing so, also reveals the reasons for his failure. He expects to find ‘the emphasis’ of the sentence in some one word or phrase, which word or phrase he expects to find in a constructure ventional position within the sentence. (Usuemphasis ally the emphatic position is taken to be early in the Greek sentence. But there is some disagreement about this. See the discussion by G. Thomson in Headlam–Thomson's Oresteia, ii. 370 ff.) It appears to me that in such sentences as this there is no conventional position of emphasis, but that the emphases within the sentence are determined by the sentence's own pattern. The Greek hearer did not jump at the first suggestion of meaning offered him, but waited until the sentence was completed, in order to decide its pattern and to relate its several elements one to another. He could do this because he was a hearer, not a visual reader. The analogy of music is a better guide than our own habits of reading. Here is a deep and fundahe mental difference between the ancient and the modern modes of interpreting the spoken or the written word, which has never been sufficiently appreciated.