No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

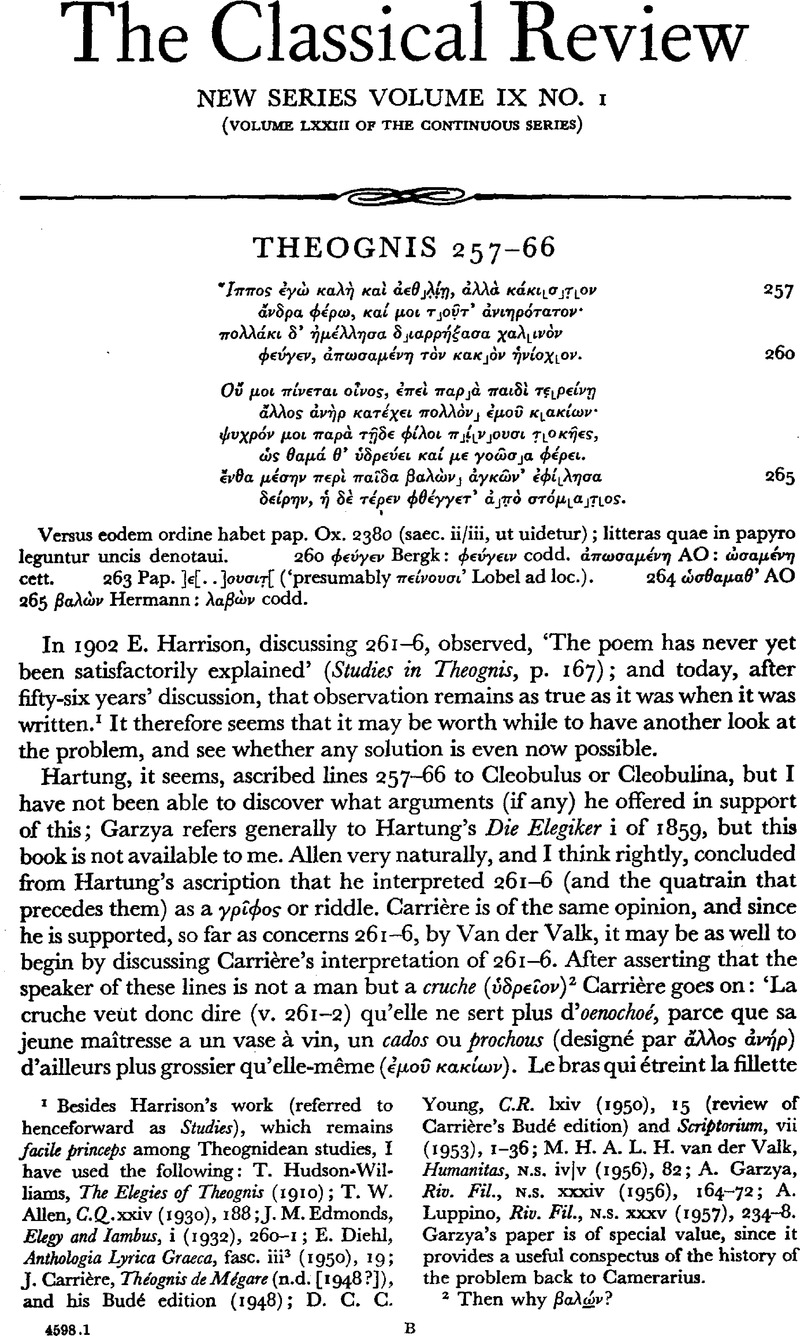

page 1 note 1 Besides Harrison's work (referred to henceforward as Studies), which remains facile princeps among Theognidean studies, I have used the following: Hudson-Williams, T., The Elegies of Theognis (1910)Google Scholar; Allen, T. W., C.Q. xxiv (1930), 188Google Scholar; Edmonds, J.M., Elegy and Iambus, i (1932), 260–261Google Scholar; Diehl, E., Anthologia Lyrica Graeca, fasc. iii3 (1950), 19Google Scholar; J. Carrière, Théognis de Mégare (n.d. [1948?]), and his Budé edition (1948); D. C. C. Young, C.R. Ixiv (1950), 15 (review of Carriere's Budé edition) and Scriptorium, vii (1953), 1–36; M. H. A. L. H. van der Valk, Humanitas, N.s. iv|v (1956), 82; A. Garzya, Riv. Fil., N.s. xxxiv (1956), 164–72; A. Luppino, Riv. Fil., N.s. xxxv (1957), 234–8. Garzya's paper is of special value, since it provides a useful conspectus of the history of the problem back to Camerarius.

page 1 note 2 Then why βαλών?

page 4 note 1 With ⋯π⋯ στ⋯ματoς here we should per-haps compare Theognis' use of ⋯π⋯ ϒλώυσης in 63 (the parallel is suggested by L.S.J.9 s.v. στ⋯μα I. 3. b); if so the suggestion is that the girl's heart is not involved. Alternatively ⋯π⋯ στ⋯ματoς here, as in Plato Theaet. 142 and elsewhere (for references, see L.S.J.9 as above), may mean ‘from memory’ or ‘by rote’. (In either case the girl is insincere the speaker knows it).