No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

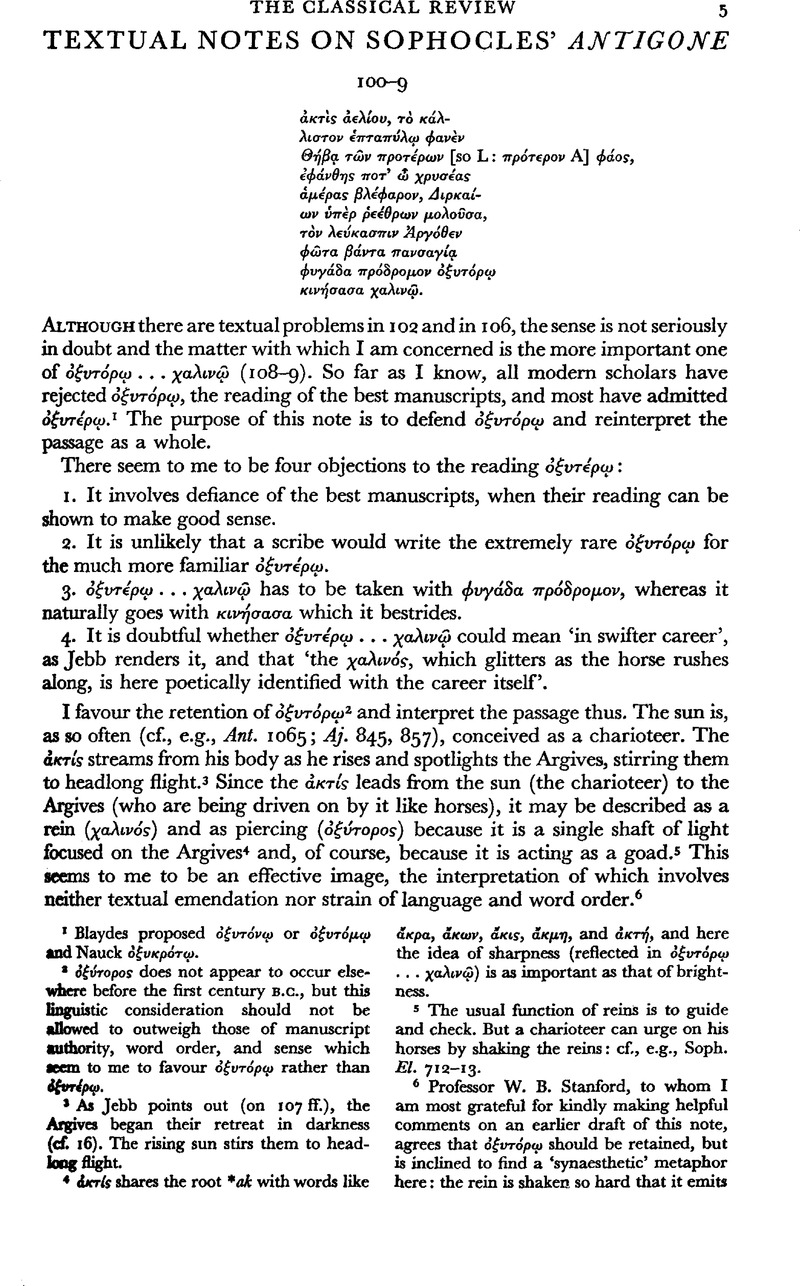

1 Blaydes proposed ὀξντόνῳ or ὀξντόμῳ and Nauck ὀξυκρότῳ.

2 ὀξύγορος does not appear to occur elsewhere before the first century B.C., but this linguistic consideration should not be allowed to outweigh those of manuscript authority, word order, and sense which seem to me to favour ὀξυτόρῳ rather than ὀξυτέρῳ.

3 As Jebb points out (on 107 ff.), the Argives began their retreat in darkness (cf. 16). The rising sun stirs them to headlong flight.

4 ἀκτίς shares the root *ak with words like ἄκρα, ἄκων, ἄκις, d ἄκμη, and ἀκτή, and here the idea of sharpness (reflected in ὀξυτόρῳ … χαλινῷ) is as important as that of brightness.

5 The usual function of reins is to guide and check. But a charioteer can urge on his horses by shaking the reins: cf., e.g., Soph. El. 713–13.

6 Professor W. B. Stanford, to whom I am most grateful for kindly making helpful comments on an earlier draft of this note, agrees that ὀξυτοόρῳ should be retained, but is inclined to find a ‘synaesthetic’ metaphor here: the rein is shaken so hard that it emits a ‘sharply-piercing’ note. He compares A. Th. 122–3 (quoted by Jebb on Ant. 107 ff.): διἀ δέ τοι γενύων ἱππίων κινύρονται ψόνον χαλινοί. Professor Stanford points out that S. is fond of terms expressing a sensation of ‘piercing’ or ‘thrilling’, especially in his choruses. (For ‘synaesthetic’ or ‘intersensal’ metaphor see Stanford's, Greek Metaphor, esp. pp. 47 ff.)Google Scholar