No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

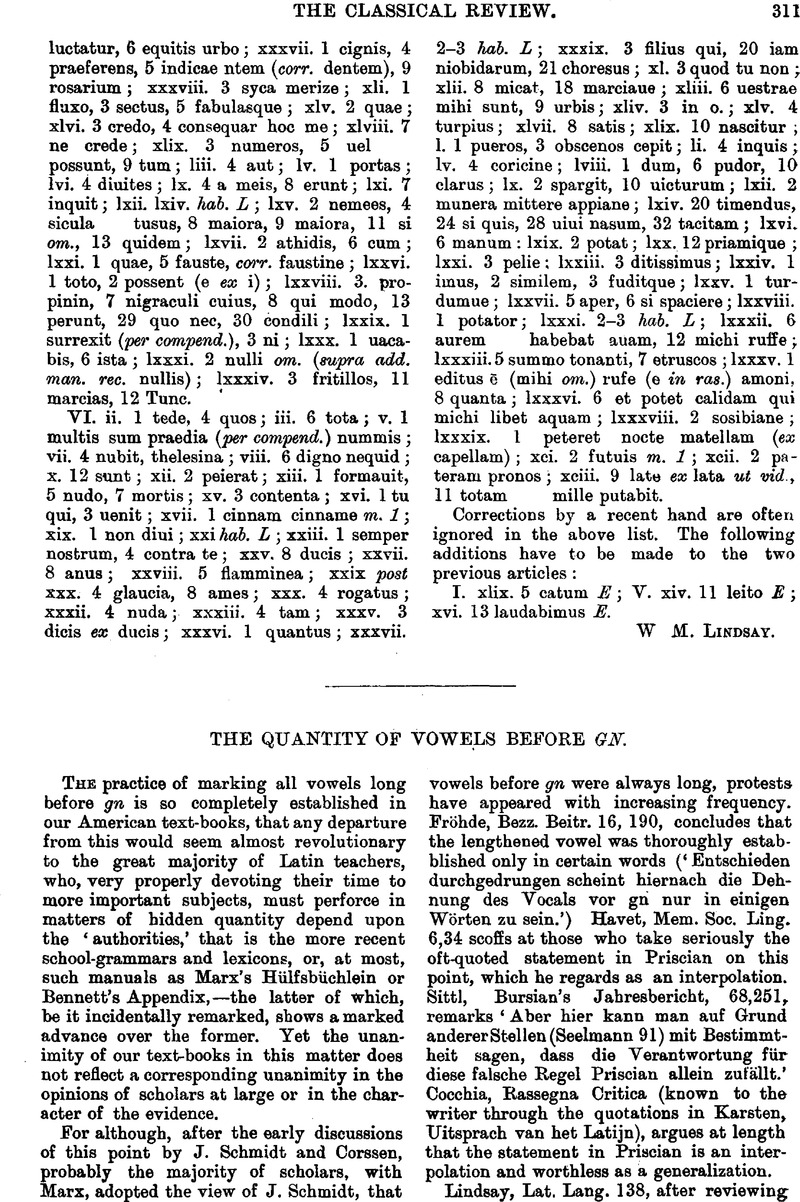

The Quantity of Vowels Before gn

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1901

References

page 312 note 1 Yet this principle is not followed out by Bennett quite consistently. If he gives so much weight to Priscian's statement as to assume vowel-length in magnus, pugna and many others for which there is no specific evidence, he should not hesitate to do the same for agnus. For the compound ambiegnus, although cited by others also (e.g. Havet I.e.) as evidence against the long vowel, really has no bearing on the question. To be sure it shows that the vowel of agnus was not long when the weakening took place. But it is well known that the weakening process antedated the vowel-lengthening before ns(cf. the relation of †hanslō, whence hālō, to †anhēslō, Whence anhēlō), and, similarly, the vowel-lengthening before gn, if such there were, would not have been early enough to interfere with the weakening process.

page 312 note 2 An additional point made by Marx, to the effect that in words like agnōscō, cognōscō the vowel of the preposition must be long because of the loss of the final d or n, would not be urged by any one to-day. This is not the kind of consonant-loss which is accompanied by vowel-lengthening.

page 312 note 3 W. Meyer's interpretation of the Romance evidence (K. Z. 30, 337), which enables him to square it with the supposed lengthening in Latin, and which would apply equally to the evidence of Germanic and Celtic borrowed words, is one which, while theoretically possible, is nevertheless distinctly improbable. It is true of course that Romance shows us the quality, and only indirectly the quantity, of Latin vowels, and that there are sometimes special factors which vitiate the usual reasoning from quality to quantity. A lengthened vowel might have the quality of the short vowel from which it came rather than that of the original long vowel, as in fact was the case in most Greek dialects and in Oscan (e.g. ligud for †lēgōd, with i for original ē, but keenzstur with ee for the e lengthened before ns).But as a matter of fact this was not the case in Latin, judging, as we are entitled to do, from the history of the lengthened vowel before ns, which gives the same result in Romance as an original long vowel.

page 312 note 4 As there is no uniformity in the marking of long vowels on inscriptions, the argumentum ex silentio is a dangerous one, and should never be given weight against positive and unconflicting evidence of length. But if the quantity of the vowel is in doubt, one's scepticism of its length is naturally increased by the absence of inscriptional evidence of length, in the case of words of very frequent occurrence. And even a single example of an apex or I longa may not be conclusive. Our text-books generally follow Marx in writing māximus. But taking into account the fact that vowel-lengthening before x is not to be admitted and that original length in this word is, to say the least, extremely improbable, we ought to attach less importance to the single example of an apex on an inscription which is not free from mistakes (e.g. immólávit) than to the fact that there is no other example, although the word occurs hundreds and hundreds of times on imperial monuments, plenty of these showing the apex in other words.

page 313 note 1 As further evidence for the short vowel have often been adduced: (1) the Greek transcription of cognitū as κογνιτου,—but this has little weight, as o is not uncommon as a transcription of Lat. ō; (2) the existence of ambiegnus beside agnus, —but this is wholly irrelevant (see above); (3) the occasional shortening in Plautus and Terence of the first syllable of ignāve, ignōbilis, etc., after short syllables,—but the usual assumption that initial syllables in which the vowel itself is long are never shortened is contested by Skutsch, Satura Viadrina.

page 313 note 2 Marius Plotius (Keil vi. 451, 5) mentions as a barbarism the prnounciation pērnix, and Pompeius (Keil v. 126, 5) refers to the mispronunciation of arma with long a. Yet Diomedes must have had this vulgar pronunciation ārma in mind in the passage (Keil i. 469) where he speaks of it as a trochee. For, as noted above, he is observing vowel-quantity, not syllabic quantity.

page 314 note 1 The attempt to draw the line exactly between words in which the pronunciation with a long vowel became established and those in which it did not, is bound to be somewhat arbitrary. Yet we can make what is probably a close approximation to the truth. The long vowel is rightfully recognized by all scholars in the case of fōrma, ōrdō, ōrnō and their derivatives, where the inscriptional evidence is unusually strong and is also confirmed by the Romance. The long vowel is almost equally certain in the case of Mārs, Mārcus, Lārs (in these proper names it may be originally long; the question need not concern us here) and in quārtus, although some scholars write, e.g., Marcus, quartus. For in these the inscriptional evidence is every whit as strong as for ōrdō, etc., and the only conceivable justification for making a distinction would be that in quartus, etc., the long vowel is not confirmed by the Romance. But, as always in the case of a-vowels, the Romance cannot either confirm or refute the length. With firmus, which appears in most of our text-books as firmus, we cross the line, at least in the judgment of the writer, to the words in which the long vowel, though known, had not become established as the usual pronunciation. Five examples of the I longa are quoted by Christiansen (De apicibus, etc.), while the Romance forms point clearly to the short vowel. If any one should take the position that, while the popular speech, as reflected in the Romance, had the short vowel, the language of the cultivated classes, the High Latin, knew only the long vowel in this word, we could only maintain the extreme improbability of this view on general grounds. This vowel lengthening before r+ consonant we do not regard as a characteristic of the cultivated speech which worked its way downward into the popular speech, but rather as a characteristic of some particular phase of popular speech, which in some words spread throughout the popular speech and lastly to the cultivated language. We regard firmus, then, as a vulgarism which was not uncommon, as shown by the number of examples with the apex, but which did not become the usual form in the popular speech, much less in the cultivated speech. Among the numerous other words in which the vowel is occasionally marked, long on inscriptions, as Hércules, fórtuna, virtus, etc., there is none in which it is at all likely that this pronunciation was generally adopted.