Article contents

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1903

References

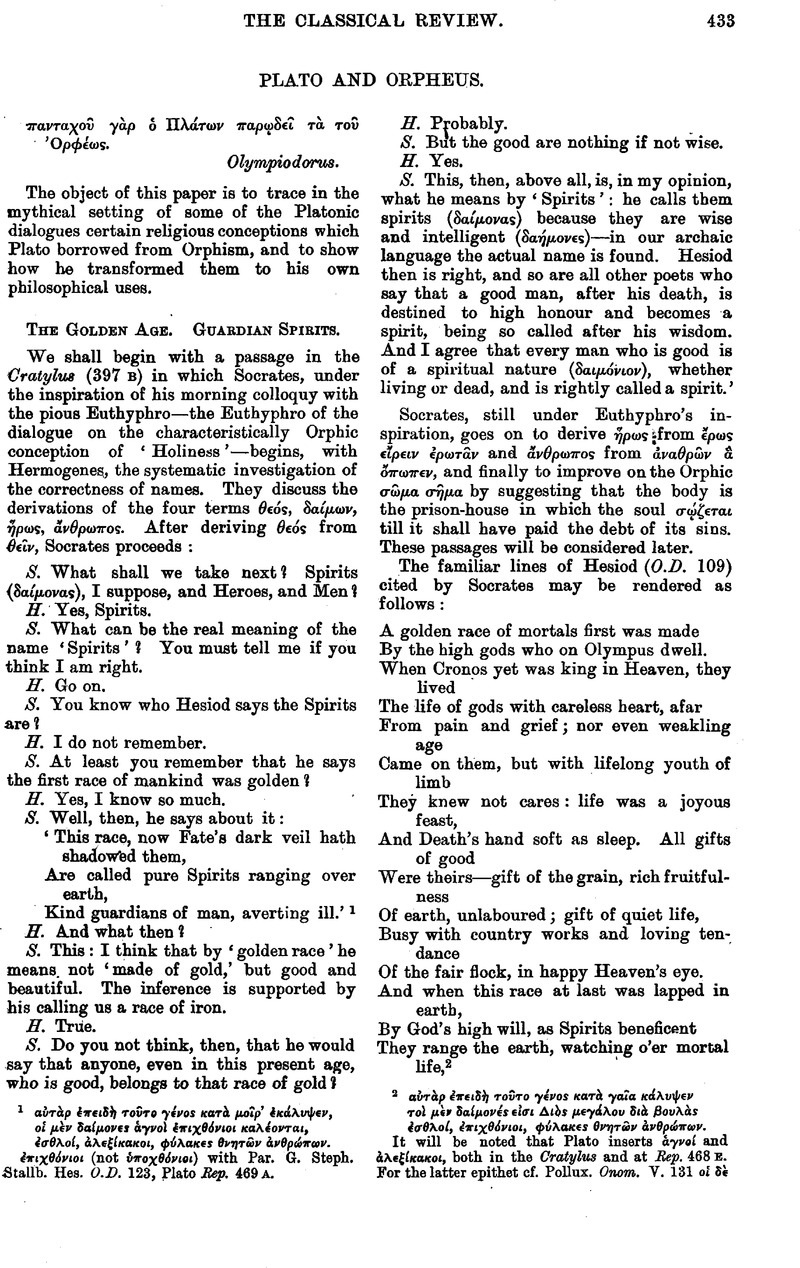

page 433 note 1 ![]() .

.

πιχθνιοι (not ὑποχθνιοι) with Par. G. Steph. Stallb. Hes. O.D. 123, Plato Rep. 469 A.

page 433 note 2 ![]() .

.

It will be noted that Plato inserts γνο and λεξκακοι, both in the Cratylus and at Rep. 468 E. For the latter epithet cf. Pollux. Onom. V. 131 ![]() .

.

page 434 note 1 δαμων φλαξ in its ordinary sense of tutelary genius, Rep. 620 E.

page 434 note 2 A hint of this subterranean nurture may have been taken from Hesiod, O.D. 130 (of the silver race): ![]() .

.

page 434 note 3 de Def. Or. X.

page 434 note 4 On Hesiod O.D. 121.

page 435 note 1 ![]() O.D. 159.

O.D. 159.

page 435 note 2 The extant Orphic poems have little about δαμονε. In the proem to the Hymns (line 32) we read of

![]() .

.

See Lobeck, , Aglaoph. p. 956Google Scholar.

page 435 note 3 Hesiod does not use ἥρως in this sense. See Rohie, Psyehe 3 p. 101.

page 436 note 1 The ceremony alluded to, Phaedrus, 250 A.

page 436 note 2 Ael. Arist. Eleus. 1. 256.

page 436 note 3 Dio. Chrys. xii. 387.

page 436 note 4 Theaet. 155 D.

page 436 note 5 Met. A. 983 a 12.

page 437 note 1 The Socratic method is to be used in that first stage of the higher education which is described at Rep. 522 B, to produce πορα (524 A) about the union of opposite sensible qualities in the same object.

page 437 note 2 It is worth noting here that in the Clouds Socrates is represented as initiating a novice in the Orphic mysteries. The whole ceremony is travestied (lines 222 ff.). Compare also Birds 1555, where Socrates is ψυχαγωγς in a λμνη λουτος.

page 437 note 3 Lysis ap. Iambl, vit. Pyth. 76.

page 437 note 4 404 E—406 A.

page 438 note 1 Compare also the analysis of καθαρτκ above, which ἰατρικ appears side by side with cathartic sophistry.

page 438 note 2 Dem. xix. 249.

page 438 note 3 Aristides, Or. 2. 171.

page 438 note 4 Aesch. Eum. 62.

page 438 note 5 See Roscher, Lex. p. 435a.

page 439 note 1 Phaedrus, 249 E.

page 439 note 2 See Miss J. E. Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

page 439 note 3 Schol. ad Aristoph. Plut. 845.

page 439 note 4 Them, περ ψυχς ap. Stob. Flor. 120, 28.

page 439 note 5 The αὐγ καθαρ of Phaedr. 250 c.

page 439 note 6 Frogs, 137–158. Trans. Murray.

page 441 note 1 Helios is, of course, familiar as the all-seeing avenger of wrong (cf. Plat. Crat. 403 B), and as the γνς θες (Pind. ol. vii, 58) who being pure, can purify: ![]() (Schol. ad loc.).

(Schol. ad loc.).

page 441 note 2 Frogs 455 trans. Murray: ![]() . Cf. also Clouds 225.

. Cf. also Clouds 225.

page 441 note 3 Eurip. Cret. frag. trans. Murray: ![]() .

.

page 441 note 4 ap. Plut. de avd. poet. v.

page 441 note 5 Crat. 405 c.

page 441 note 6 We know from Paus. i. 30. 2 that the Academy contained ‘an altar of the Muses, and another Hermes.’ The juxtaposition is significant.

page 441 note 7 Phaedr. 247.

page 441 note 8 Lobeck, Aglaoph. p. 14a ; Thompson on Phaedr. 250 B.

page 442 note 1 Aristotle, Eth. K. 7 1177b 30.

page 442 note 2 Phaedo 82 B. Compare the derivations of Zeus, Kronos, Ouranos, Crat. 396 : Zeus, the ruler and king of all is ![]() , his father is a great understanding (δινοια); his name means

, his father is a great understanding (δινοια); his name means ![]() . He is son of Ouranos,

. He is son of Ouranos, ![]() , whence οἱ μετεωρλογοι say they acquire τν καθαρν νον. The allegory is transparent: the wisdom that looks upward begets pure reason, the source of all life. I cannot agree with Lobeck (Aglaoph. 510 [f]) that Plato's intention is merely derisive.

, whence οἱ μετεωρλογοι say they acquire τν καθαρν νον. The allegory is transparent: the wisdom that looks upward begets pure reason, the source of all life. I cannot agree with Lobeck (Aglaoph. 510 [f]) that Plato's intention is merely derisive.

page 442 note 3 vit. Rom. 28.

page 442 note 4 (Zeller, Phil. d. Gr. iii 2. p. 192, ed. 4. 1903). For Plutarch's demonology see de Is. et Os. xxv–xxvi. Compare also de Def. Orac. x, where after the passage already quoted (p. 434 note 3) he continues : ‘ But others hold an analogous transformation for bodies and for souls. (For bodies) out of earth comes water, out of water air, and out of air fire is seen generated, the essence being carried upwards. Similarly the better souls take their transformation from men into heroes, from heroes into spirits ; and from spirits a few, after long time, being altogether purified through virtue, participate in divinity’: ‘but others cannot master themselves, but enter again into mortal bodies, and have a dim and murky life, like vapours’. See also the experiences of Timarchus, a contemporary of Socrates, in the Cave of Trophonios (Plut. de gen. Socr. xxii). Whatever view we take of this passage, it is a most important commentary on the vision of Er.

page 442 note 5 Rep. 487 E.

page 442 note 6 de fac. in orbe Lun. 30.

page 443 note 1 The very turn of the phrase echoes Rep. 487 E ![]() , with significant substitution of θες for φιλσοφος.

, with significant substitution of θες for φιλσοφος.

page 443 note 2 90 A. trans. Archer-Hind.

page 444 note 1 Like the φιλα and νεῖκος of Empedocles.

page 444 note 2 Plato rarely invents the imagery of his myths. Even this notion of living backwards will be found in a curious legend preserved by Theopompus, frag. 76. Since I wrote this Dr. Adam has kindly drawn my attention to his interesting discussion of this myth in his edition of the Republic, vol. ii. pp. 295 ff.

- 2

- Cited by