Article contents

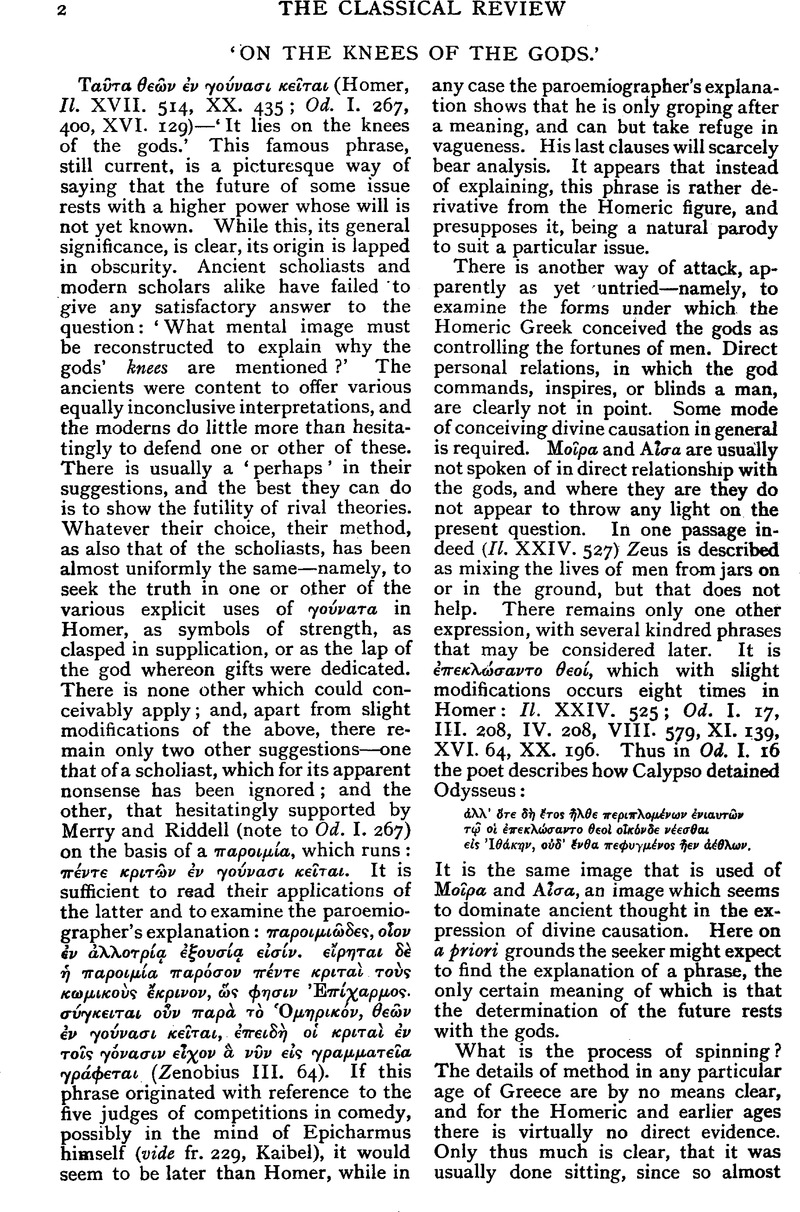

‘On the Knees of the Gods.’

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1924

References

page 3 note 1 Spinn- und Webewerkzeuge, Entwicklung und Anwendung in vorgeschichtlicher Zeit Europas, Würzburg, 1910, p. M61.Google Scholar

page 3 note 2 Vide SirWilkinson's, G.Ancient Egyptians, ed. Birch, 1878, Vol. I., p. 378, Fig. 8, from the wall-paintings of Beni Hassan.Google Scholar

page 5 note 1 Schrader, , Reallexicon der Indogermanischen Altertumskunde, 1901, pp. 791 and 939.Google Scholar

page 6 note 1 Verhandl. der Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie u.s.w., 1896, p. 473.Google Scholar

page 6 note 2 See the pictures from Beni Hassan cited above. A similar method still in use among the peasants around Hermannstadt (Siebenbürgen) is described by Kimakowicz, pp. 61–63.

page 6 note 3 Apart from Homer, Blümner cites nothing earlier than the Anth. Pal., save Eurip. Orestes, 1431, which he cites again (p. 227) as illustrating the use of ελίσσειν for the turning of the spindle. It runs: ![]() . If his meanings for ελίσσειν and ἠλακάτᾳ are correct, it is difficult to see what kind of dative the latter can be. If, however, ἠλακάτη here also means spindle, the sense is simple, and we have another instance of the double instrumental dative, parallel to Sophocles, Ajax, 229:

. If his meanings for ελίσσειν and ἠλακάτᾳ are correct, it is difficult to see what kind of dative the latter can be. If, however, ἠλακάτη here also means spindle, the sense is simple, and we have another instance of the double instrumental dative, parallel to Sophocles, Ajax, 229: ![]() , where χερὶ corresponds to δακτύλοις and ξίφεσι to ἠλακάτᾳ.

, where χερὶ corresponds to δακτύλοις and ξίφεσι to ἠλακάτᾳ.

page 6 note 4 Vide Ling Roth, Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 1916, p. 290.

page 6 note 5 Troja, Note XVI.

page 6 note 6 Dörpfeld, Troja und Ilion, pp. 390 and 400.

page 6 note 7 Rep. X. 616c.

page 6 note 8 Blümner, Figs. 48 and 531.

- 1

- Cited by