No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

page 69 note 1 The important difference is that where in the Choeþhori the lyric stanzas are separated by anapaests, in our passage there are dactyls.

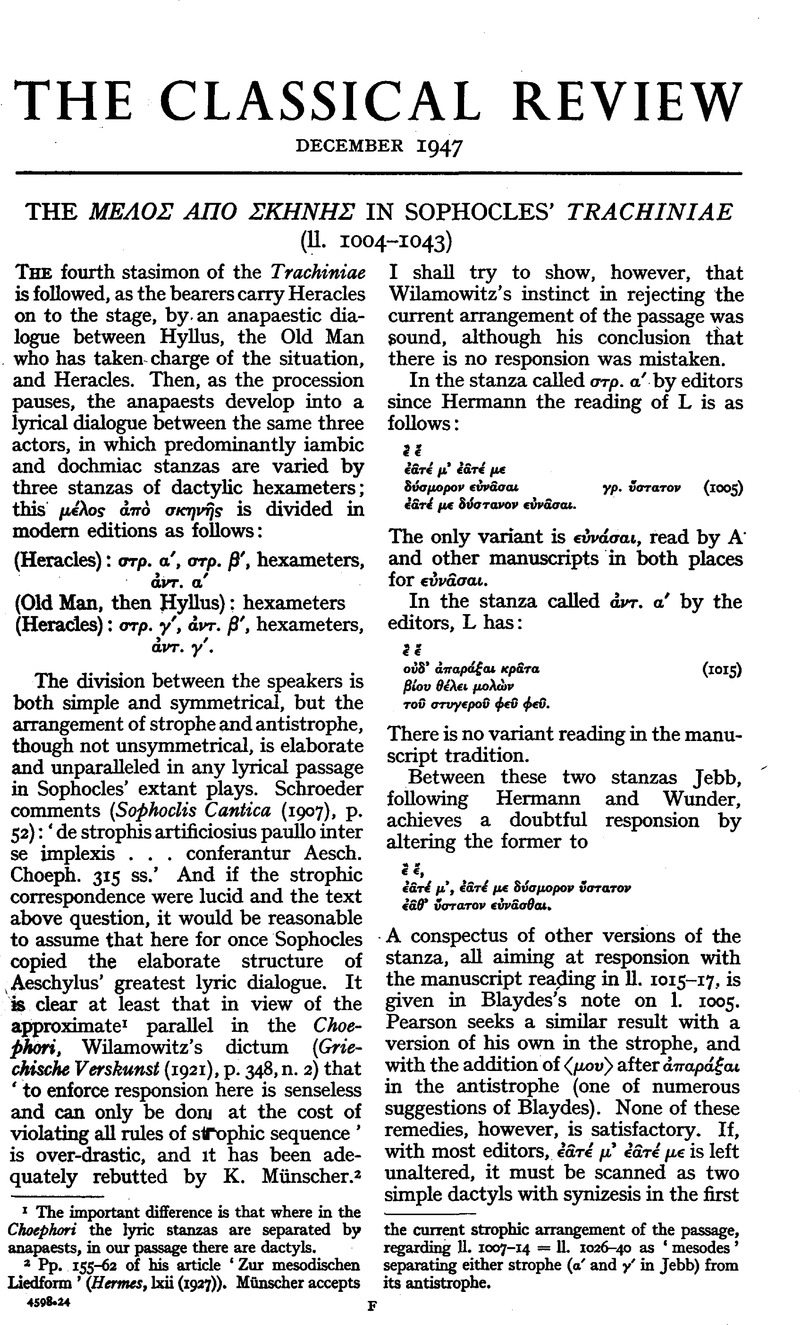

page 69 note 2 Pp. 155–62 of his article ‘Zur mesodischen Iiedform’ (Hermes, lxii (1927)). Münscher accepts the current strophic arrangement of the passage, regarding 11. 1007–14 = 11. 1026–40 as ‘mesodes’ separating either strophe (ά and ý in Jebb) from its antistrophe.Google Scholar

page 70 note 1 El. 157–8 = 177–8 and similar passagesare not relevant, since spondees are here admitted among the dactyls in the strophe.

page 71 note 1 Pindar frequently repeats complete words in the same metrical position, but often only the sound, e.g. Ol. i. 3 ἄτε διαπρ⋯πει = 19 Σικελ⋯ᾳ δρ⋯πων; 25. I quote a single illustration each from Aeschylus and Euripides: Cho. 156 ἔτυψεν δ⋯καν διφρηλ⋯του = 163 κρατο⋯ντες τ⋯ π⋯ν δ⋯κας πλ⋯ον, Hippol. 550—I δρομ⋯δα Ναΐδ' ⋯πως τε Β⋯κχαν σὺν αἵματι σὺν καπνῷ = 560—1 τοκ⋯δα τ⋯ν διγ⋯νοιο Β⋯κχου νυμφευσαμ⋯να π⋯τμῳ. Such echoes occur even in lyric trimeters standing in responsion; cf. the striking repetition of the sound of ⋯παρ in Soph. Aj. 892 τ⋯μος βο⋯ π⋯ραυλος ⋯ξ⋯βη ν⋯πους = 938 χωρεῖ πρ⋯ς ἧπαρ, οἶδα, γεννα⋯α δ⋯η. This shows that they are not due to a simple tendency to rhyming in the same metrical position (which would produce a proportion of echoes in non-lyrical trimeters), but are a result of the essentially musical nature of Greek lyric composition. The dominance of the musical form is such that its repetition can deter mine for the poet the very acoustic value of his words. The identical phenomenon is found in Homer, conspicuously in assonances like that between ζ 122 ⋯μφ⋯λυθε θ⋯λυς ⋯. These epic assonances are similarly due to the psychological effect on the poet, as he seeks for a phrase of a given metrical and musical value, of an already existing phrase of that value (cf. Parry, Milman, ĽÉpith`te traditionneUe dans Hom`re, pp. 90 if., who shows conclusively that they are a product ofthe technique of oral composition). It is apparent how much closer to the epic technique is the art of lyric composition than of that of the composition.Google Scholar

page 72 note 1 The inversion of το⋯ στυγερ⋯ and μολών and the supposition of a lacuna after φε⋯ are the φε⋯proposals of Erfurdt which Hermann suppressed owing to his acceptance of Seidler's metrical analysis.