No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

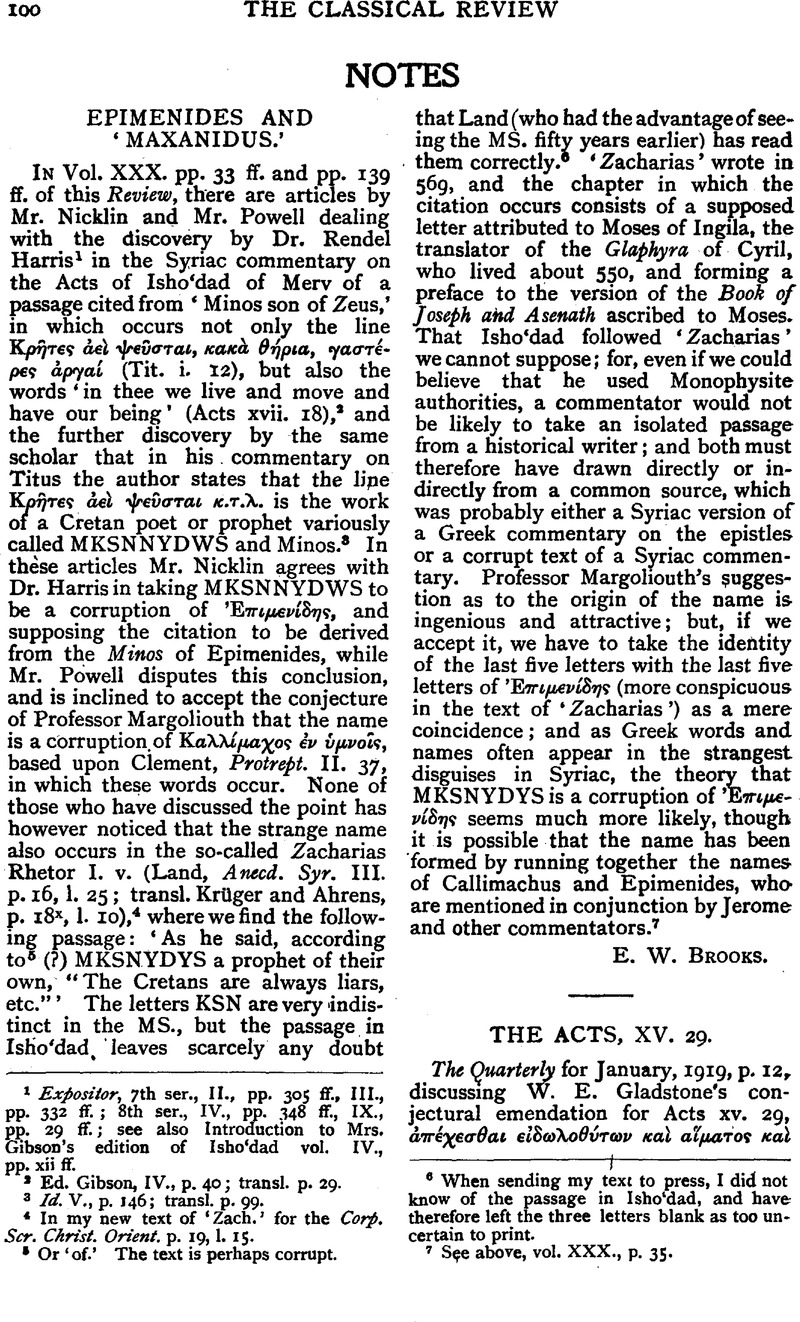

page 100 note 1 Expositor, 7th ser., II., pp. 305 ff., III., pp. 332 ff. ; 8th ser., IV., pp. 348 ff., IX., pp. 29 ff.; see also Introduction to Mrs. Gibson's edition of Isho'dad vol. IV., pp. xii ff.

page 100 note 2 Ed. Gibson, IV., p. 40; transl. p. 29.

page 100 note 3 Id. V., p. 146; transl. p. 99.

page 100 note 4 In my new text of ‘Zach.’ for the Corp Ser. Christ. Orient, p. 19, 1. 15.

page 100 note 5 Or ‘of.’ The text is perhaps corrupt.

page 100 note 6 When sending my text to press, I did not know of the passage in Isho'dad, and have therefore left the three letters blank as toouncertain to print.

page 100 note 7 See above, vol. XXX., p. 35.

page 100 note 1 πνικτ⋯ν V. L. (LTTr) πνικτο⋯.

page 102 note 1 Cf. Lex Acil. 70 (Bruns', Fontes, p. 70Google Scholar) for ways of hindering a trial, and see the cases of retirement of accusers cited by Greenidge, in Legal Procedure of Cicero's Time, p. 468Google Scholar, n. 1. Cf. also Orationes Claudii, Bruns, , pp. 98–99Google Scholar.

page 102 note 2 Cic. pro Balb. 28, 65 : ‘Cum omnium peccatorum quaestiones sint,’ quoted by Greenidge; p. 427.

page 102 note 3 Strachan-Davidson, , Roman Criminal Law, i. 201Google Scholar; Botsford, , Roman Assemblies, p. 258Google Scholar.

page 102 note 4 See 26, Bruns, p. 64.

page 102 note 6 2 Fam. viii. 8, 3.

page 102 note 7 Cf. Cic. de Or. ii. 58, 236 : res … ioco risuque dissolvit.

Quint, v. 10, 67: cum risu tota res solvitur. Class. Rev. XXXI. 52 (March, 1917).

page 103 note 1 Class. Rev. XIX. 400 ff. (November, 1905).

page 103 note 2 Der Echte und der Unechte Juvenal, p. 54.

page 104 note 1 The poet, of course, did not seriously believe in an abode where souls appeared before birth in their future attributes.

page 107 note 1 Nash (1874); Capes (1878); Dowdall (1885); Dimsdale (1888); Tatham (1889); Trayes (1899); Allcroft and Hayes (1902). Westcott (1892) tries to evade the difficulty by translating ‘an amount of gold of the value of 400 aurei.’ But this does excessive violence to Livy's language.

page 107 note 2 Hist. Naturalis 33. 47 : aureus nummus post annos li. percussus est quam argenteus.

page 107 note 3 This date, which some scholars reject in favour of 218 B.C., has recently been rehabilitated by Leuze, (Zeitschrift für Numismatik, 1915 PP. 37–46)Google Scholar.

page 107 note 4 E.g., 22. 23.3: axgenti ponao bina et selibras in militem praestaret.

page 108 note 1 Grueber, , Coins of the Roman Republic, introd. p. lv; vol. i., p. 12Google Scholar. Hill, , Historical Roman Coins, pp. 40–43Google Scholar. Hill's date (c. 242 B.C.) commends itself strongly on historical grounds.

page 108 note 2 Cf. Head, Historia Numorum and the British Museum Catalogue of Coins.

page 108 note 3 The inconvenience of silver money to an army in rapid motion is amusingly illustrated in Oman, , History ef the Peninsular War, vol. ii., p. 348Google Scholar.

page 108 note 4 This is particularly true of the copious issues described in Evans', Horsemen of Tarentum, pp. 81–82, 97, 140–1Google Scholar.

page 109 note 1 Classical Review, May–June, 1919, pp. 68–9.

page 109 note 2 Ad Familiares 8. 11. 3 : Pompeius, tamquam Caesaremnon impugnet, sed quod illi aequum putet constituat ait Curionem quaerere discordias.