No CrossRef data available.

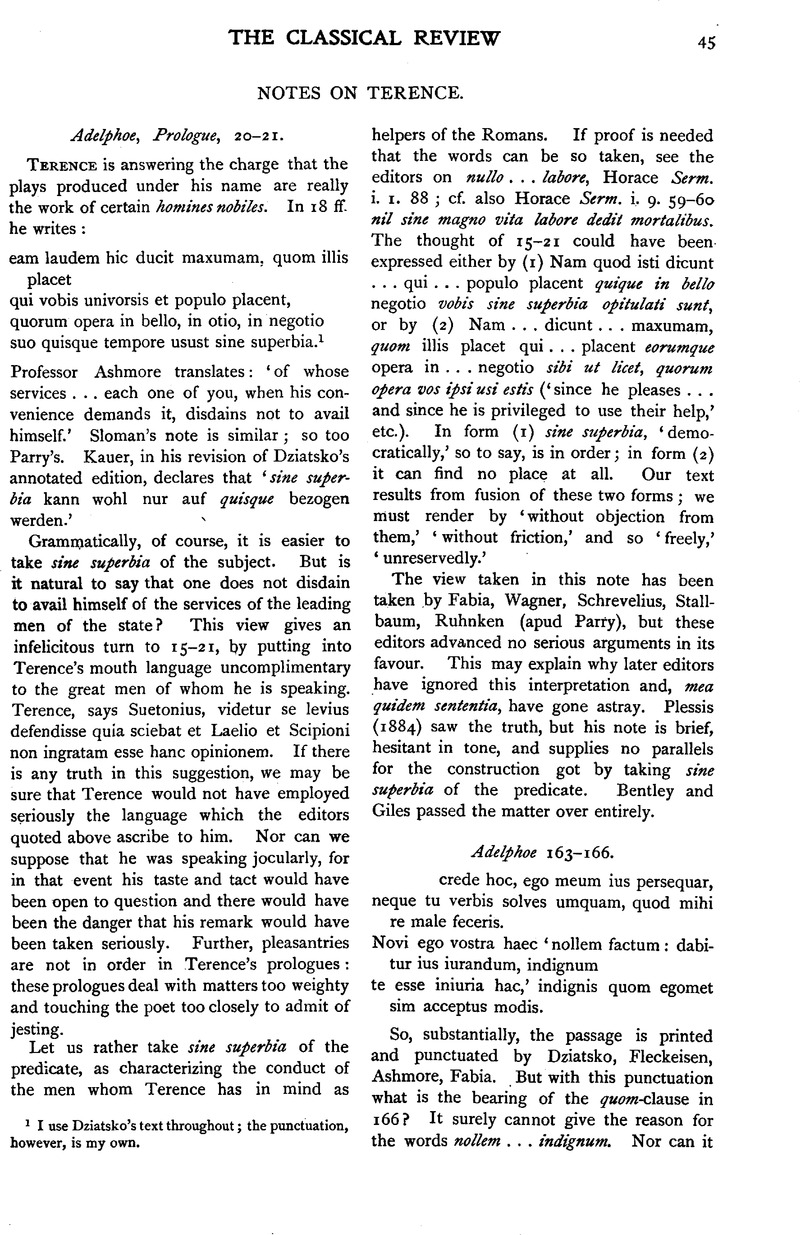

page 47 note 1 I use Dziatsko's text throughout; the punctuation, however, is my own.

page 46 note 1 This explanation is not new: cf. e.g. Bennett on the passage. No doubt many taught it before Professor Bennett's book was published. It avoids entirely the logical difficulty which some have felt here: see e.g. Wickham ad loc. and Earle, , Proc. Amer. Phil. Assoc. xxxiv. (1903), pp. xxii, xxiiiGoogle Scholar. Emendation is needless, nay, spoils the passage.

page 46 note 2 Amphit. 1132, cited as an example of this Entwertung, is not germane. In 1127 Amphitruo, sadly bewildered, cries: Ego Teresiam coniectorem advocabo et consulam quid faciundum censeat. Stage thunder is then heard, and Jupiter says: hariolos, haruspices mitte omnes: quae futura et quae facta eloquar, multo adeo melius quom illi, quom sum Iuppiter. There is nothing here discreditable to harioli or haruspices: the father of gods and king of men will himself tell all, so that appeal to the human mouthpieces of the gods is needless. In prose we should have had (ego) eloquar.

page 47 note 1 I have verified his list by the collections of Professor Lodge, the author of the monumental Lexicon Plautinum.

page 47 note 2 In Cas. 353–356, Most. 571 certe hic homo inanis est. TR. Hic homo est certe hariolus, Rud. 1139, Poen. 791 hariolus (hariola) = ‘a speaker of truth.’ In Am. 1132, Men. 76, Mil. 693, Truc. 602, the only other passages in which the noun occurs, it certainly does not = nugator. Parry's index cites hariolor from Terence only twice, in the places already discussed. It cites hariolus only from Phorm. 708, where Geta is saying, ‘We can advance excuses enough for breaking off the marriage: interdixit hariolus, haruspex vetuit. Here, surely, the hariolus is not a nugator, but one whose utterances are received with respect.