No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

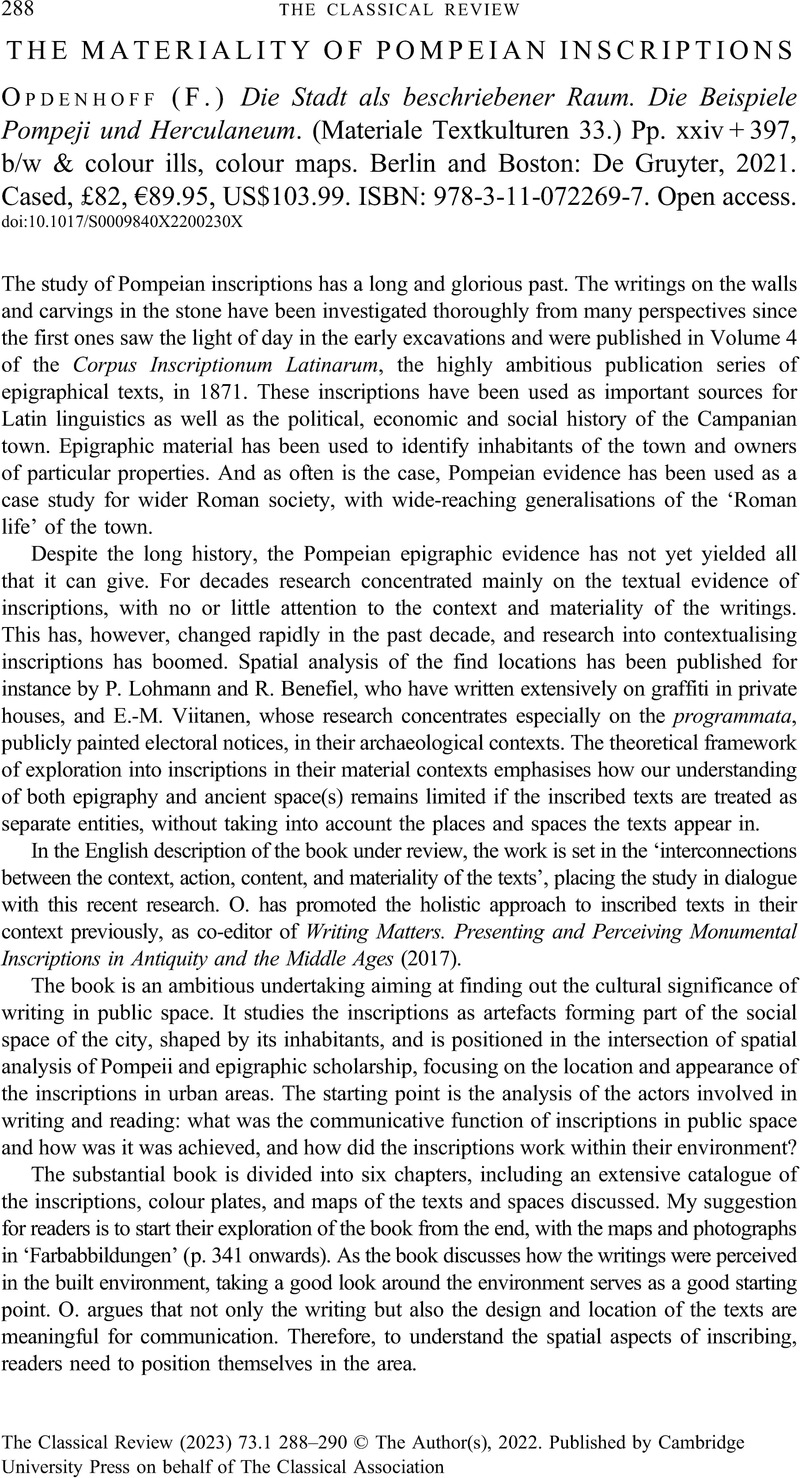

THE MATERIALITY OF POMPEIAN INSCRIPTIONS - (F.) Opdenhoff Die Stadt als beschriebener Raum. Die Beispiele Pompeji und Herculaneum. (Materiale Textkulturen 33.) Pp. xxiv + 397, b/w & colour ills, colour maps. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2021. Cased, £82, €89.95, US$103.99. ISBN: 978-3-11-072269-7. Open access.

Review products

(F.) Opdenhoff Die Stadt als beschriebener Raum. Die Beispiele Pompeji und Herculaneum. (Materiale Textkulturen 33.) Pp. xxiv + 397, b/w & colour ills, colour maps. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2021. Cased, £82, €89.95, US$103.99. ISBN: 978-3-11-072269-7. Open access.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 November 2022

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association