Article contents

Lucretius iii. 658

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1970

References

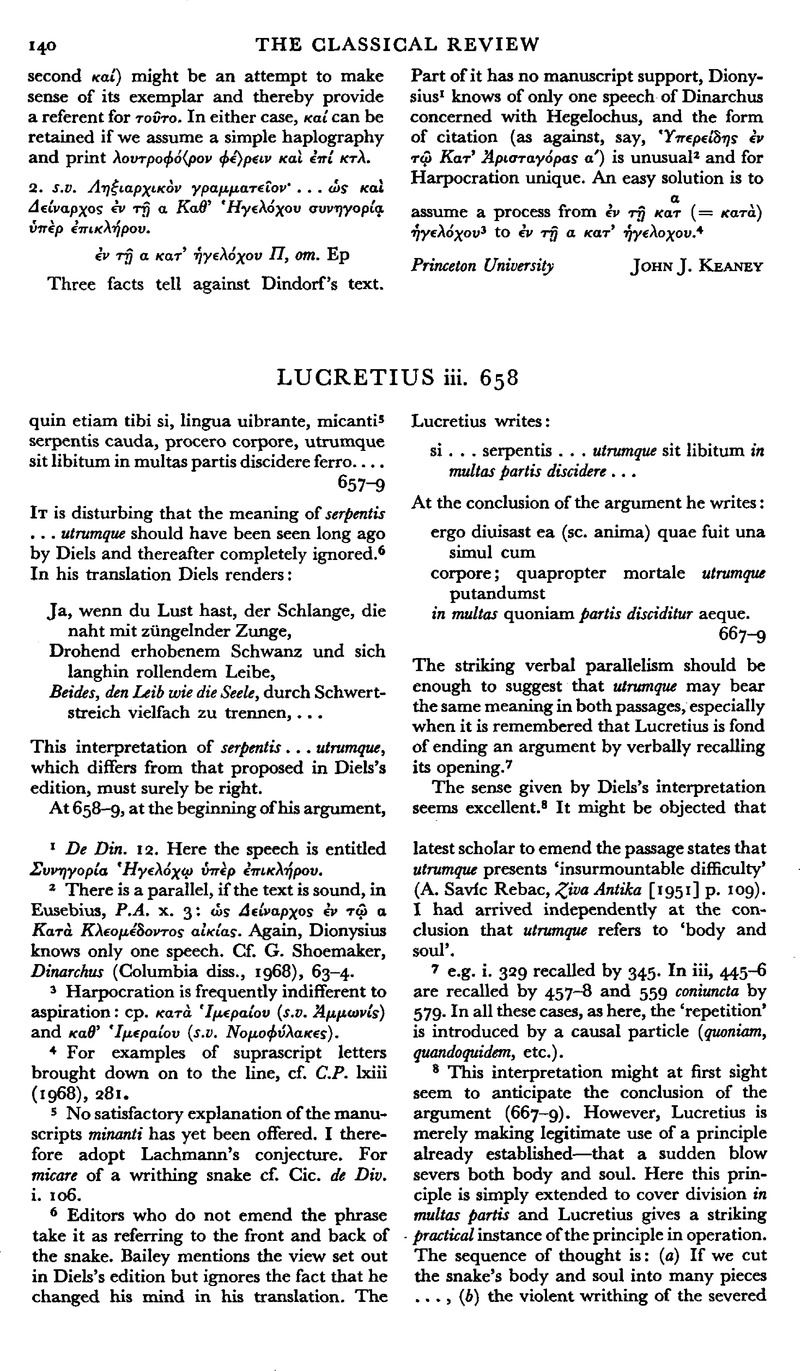

page 140 note 5 No satisfactory explanation of the manuscripts minanti has yet been offered. I therefore adopt Lachmann's conjecture. For micare of a writhing snake cf. Cic. de Div. i. 106.

page 140 note 6 Editors who do not emend the phrase take it as referring to the front and back of the snake. Bailey mentions the view set out in Diels's edition but ignores the fact that he changed his mind in his translation. The latest scholar to emend the passage states that utrumque presents ‘insurmountable difficulty’ (A. Savíc Rebac, Ziva Antika [1951] p. 109). I had arrived independently at the conclusion that utrumque refers to ‘body and soul’.

page 140 note 7 e.g. i. 329 recalled by 345. In iii, 445–6 are recalled by 457–8 and 559 coniuncta by 579. In all these cases, as here, the ‘repetition’ is introduced by a causal particle (quoniam, quandoquidem, etc.).

page 140 note 8 This interpretation might at first sight seem to anticipate the conclusion of the argument (667–9). However, Lucretius is merely making legitimate use of a principle already established—that a sudden blow severs both body and soul. Here this principle is simply extended to cover division in multas partis and Lucretius gives a striking practical instance of the principle in operation. The sequence of thought is: (a) If we cut the snake's body and soul into many pieces…, (b) the violent writhing of the severed.

page 141 note 1 e.g. iii. 487 and 592 (introducing a proof based on the same general idea as the previous one).

page 141 note 2 Most obviously the difficulty of referring utrumque to two parts of the snake's body when Lucretius has just mentioned three parts (lingua, cauda, corpus). There also seems no good reason why Lucretius should choose to represent the snake as being cut in two before it is further cut up.

- 1

- Cited by