No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 13 February 2009

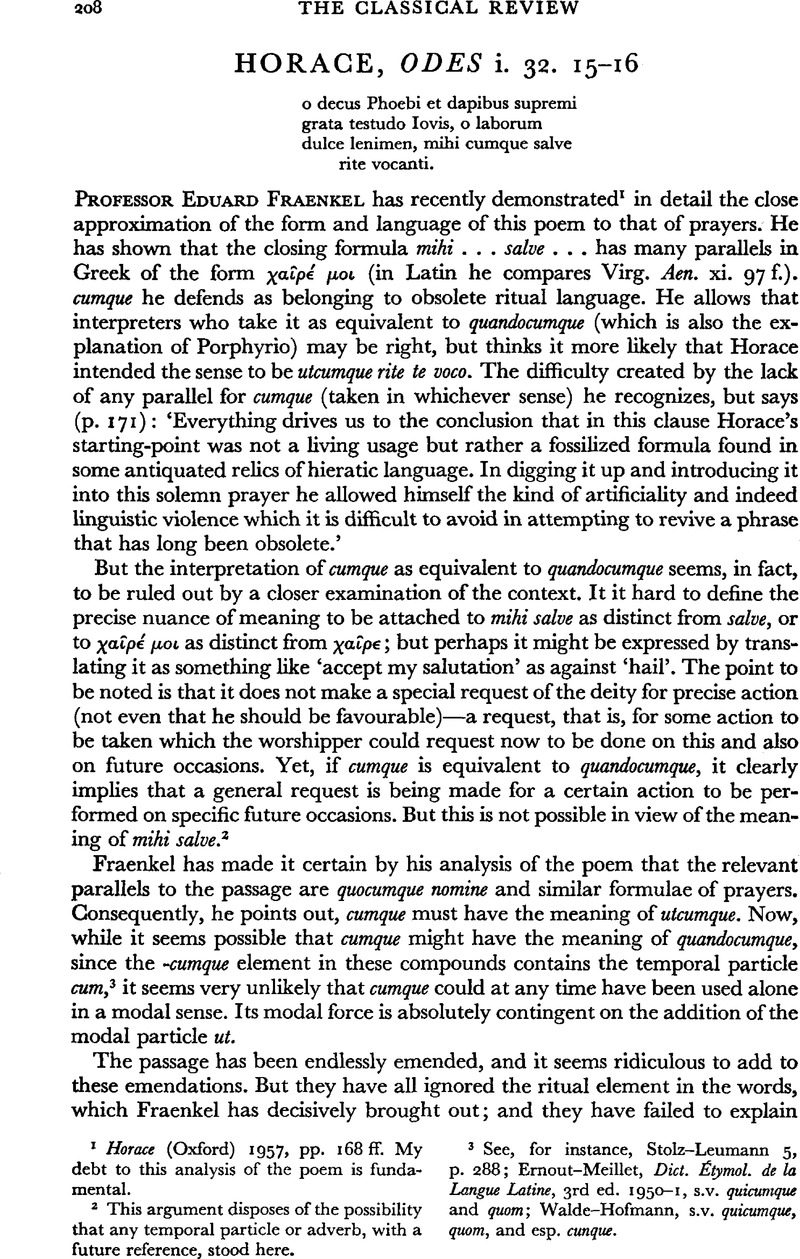

page 208 note 1 Horace (Oxford) 1957, pp. 168 ff. My debt to this analysis of the poem is fundamental.

page 208 note 2 This argument disposes of the possibility that any temporal particle or adverb, with a future reference, stood here.

page 208 note 3 See, for instance, Stolz–Leumann 5, p. 288; Ernout–Meillet, Diet. Étymol. de la Langue Latine, 3rd ed. 1950–1, s.v. quicumque and quom; Walde–Hofmann, s.v. quicumque, quom, and esp. cunque.

page 209 note 1 This is made certain, not only by Fraenkel's parallels for the dative in Greek prayers, or by the parallels at Aen. xi. 97 and Plaut. Stich. 585 (see below), but by the fact that mihi is essential to the sense—the only reference to the worshipper has been the first person plurals in the first stanza.

page 209 note 2 This was baldly stated by ancient grammarians: Priscian iii. p. 138, 15 Keil: ‘invenitur quisque pro quicumque, qualisque pro qualiscumque, similiter adverbia quoque pro quocumque, quaque pro quacumque, quandoque pro quandocumque.’ P. Ferrarino, ‘Cumque e i composti di que’ (Memorie delta R. Accademia delle Scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna, Classe di Scienze Morali, serie iv, volume iv, 1941–2), pp. 144 ff., has drawn a carefully observed distinction between quisque and quisquis in these phrases, which might be roughly ex-pressed by saying that quisque implies ‘each and every'’, quisquis ‘any at all’. (It is unreference fortunate that Ferrarino ignored the epiperson graphic evidence as well as the important passage of Terence mentioned below.)

page 209 note 3 For the stylistic level of imperitare, see pro Fraenkel, op. cit., p. 191 n. 5.

page 209 note 4 For its occurrence in inscriptions, see Dessau, I.L.S. iii. 2, index p. 860 s.v. For its occasional occurrence in later Latin, see Wölfffin, A.L.L. vii. 476.

page 209 note 5 See Lindsay, Latin Language, p. 560, and Kühner—Holzweissig, p. 1017.

page 210 note 1 For the doublet rite—ritu, cf. nocte—noctu and die—diu. noctu was still being used a noun by Ennius, Plautus, and Cato.

page 210 note 2 It seems to the present writer that there is, in fact, another instance in Carm. Epigr. 1966. 9 rite quod aeterno migrarim dedita Christo. Most editors take aeterno with Christo, but Lundstrom (Eranos, xiv, 167) points out that the epithet is not used with Christus and is here quite otiose. He takes aeterno as dative of motion; but the awkwardness and artificiality of this is unlikely in so competent an epitaph. It is better to take aeterno with rife: the quality of a Christian's religious devotion is often described on the epitaphs. Here the woman's devotion is eternal aeterno rite dedita Christo, and this is the important fact on which all else depends: ‘my husband knows that I have gone hence in eternal devotion to Christ and that in the better (heavenly) life I wear a well-deserved crown’(rather than‘my husband knows that I have gone to eternity duly devoted to Christ’).

page 210 note 3 It is noteworthy that most of the arand chaisms in Statius discussed by Klotz (A.L.L. xv. 401 ff.) occur also in Horace, and that Statius clearly owed them not to study of archaic texts, but to Ciceronian and post Ciceronian authors (see Kroll, Studien z. Verständnis der röm. Lit., p. 255 n. 16).

page 210 note 4 See Norden, Agnostos Theos, pp. 144 ff.

page 211 note 1 Cf. Apul. Met. xi. 2. 3.

page 211 note 2 Direct quotations, such as that from the old nursery-rhyme in Epist. i. 1. 59, which are signalled as quotations, are not relevant here.

page 211 note 3 See the excellent discussion of the practice of Greek authors by Stemplinger, Das Plagiat in der griechischen Literatur, pp. 241–75.

page 211 note 4 For instance, the nice adaptation of Ennius' volito vivus per ora virum in Georg. iii. 9 victorque virum volitareper ora; or Georg. iii. 76 from storks to colts or Aen. iv. 404 from elephants to ants. But it happens with the humbler borrowings as well.

page 211 note 5 The construction of quicumque with ellipse of a finite verb becomes frequent from the time of Cicero.

page 211 note 6 See in general Madvig, de Fin., Excursus vi, and Schmalz–Hofmann5, p. 486; and in particular Caesar, B.G. v. 12. 2; Sallust, Cat. 28. 4; 40. 6; Cicero, Att. v. 9. 2; v. 10. 5; de Div. ii. 24.

page 211 note 7 Note the way in which quisque is used by Horace himself: Sat. ii. 8. 77 in lecto quoque videres stridere … susurros; Epist. i. 18. 68 quid de quoque viro…; Sat. i. 4. 106 vitiorum quaquee notando (cf. ii. 3. 2 scriptorum quaeque retexens).

page 211 note 8 i.e. referring primarily to the way in which Horace has already addressed the lyre, exhausting the possibilities by addressing it in its relationship to the gods and then to the poet on earth, enumerating each point singly and distinctly.

page 212 note 1 There are other uncertainties of this sort in the highly poetical and artificial language which Horace was compelled to invent for his Odes: for example, it is not possible to say what is the precise meaning and syntactical value of neglegens in iii. 8. 25; it is obviously a bold adaptation, but not to be emended on that account.

page 212 note 2 In somewhat the same way, he has combined the archaising tmesis with a modern independent construction of quando cumque in Sat. i. 9. 33 garrulus hunc quando consumet cumque.

page 212 note 3 On cumque used for cum in late Latin, see Weyman, A.L.L. xv. 578; Glotta, iii (1912), 193.

page 212 note 4 Cf. e.g. Odes iv. 1. 17; 2.34. See Schmalz Hofmann5, p. 741, and Ferrarino, op. cit., pp. 102 ff. This experiment recommended itself to later poets; but quoque rite presum ably did not, with the possible exception of Statius.