Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

page 250 note 4 Piccolos had already proposed οἶδα θιγών τ' Ἀἶδα, but Paton's parenthetic οἶδα is not uncharacteristic (e.g. Soph. Aj. 98, 560, 938, El. 354, O.C. 1615, fr. 258 P; Eur. El. 684, Hel. 253), and it is remarkable that, in Aj. 938, οἶδα is corrupted to ἤδε in nonnulli mss. (Blaydes; cf. Porson, Adv. p. 194), while, in Eur. Med. 977, οἶδα L is corrected to ἦδη.

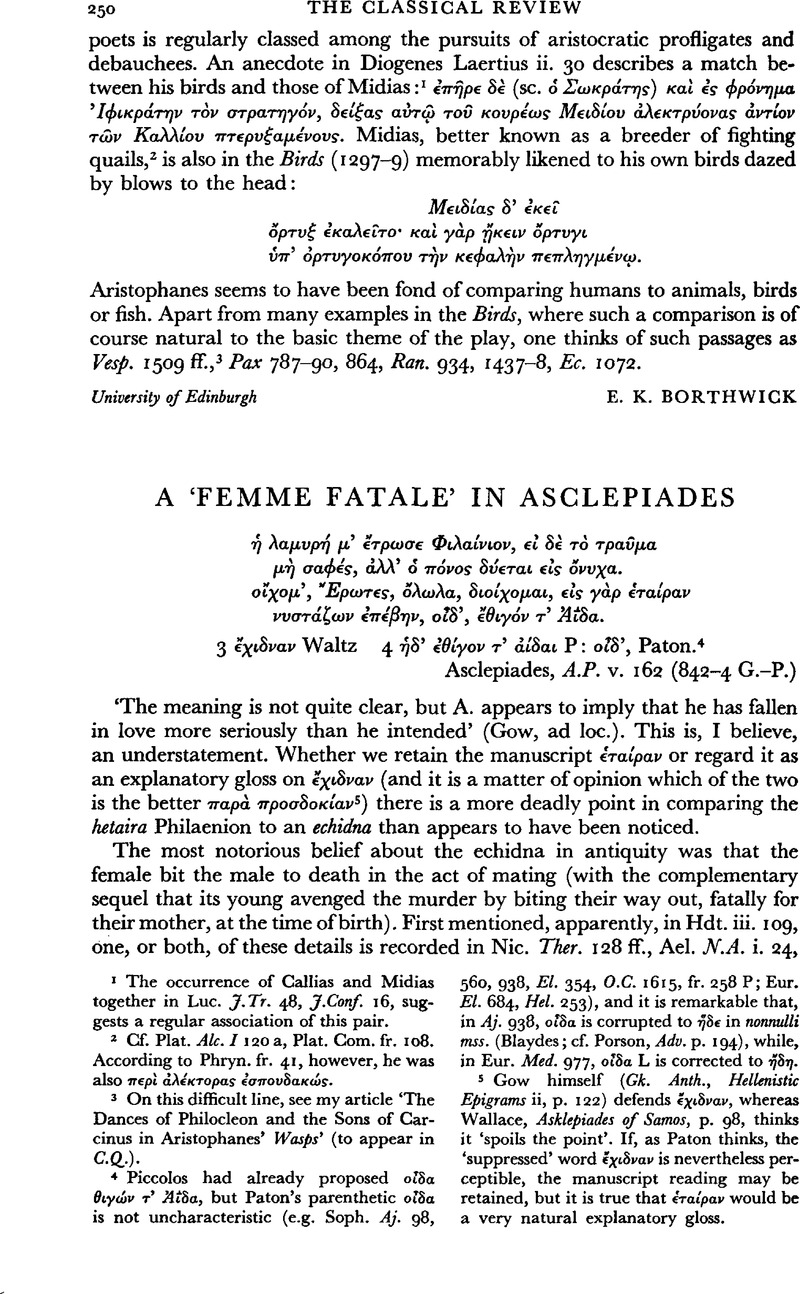

page 250 note 5 Gow himself (Gk. Anth., Hellenistic Epigrams ii, p. 122) defends ἔχιδναν, whereas Wallace, Asklepiades of Samos, p. 98, thinks it ‘spoils the point’. If, as Paton thinks, the ‘suppressed’ word ἔχιδναν is nevertheless perceptible, the manuscript reading may be retained, but it is true that ⋯τα⋯ραν would be a very natural explanatory gloss.

page 251 note 1 With Morel's Νικανδρικ⋯ς for manuscript Πινδαρικ⋯ς (Hermes lxv [1930], 367).

page 251 note 2 I suppose it may also be alluded to when Plato (Symp. 218 a) makes Alcibiades confess to the echidna-like bite of philosophy after his celebrated nocturnal experience with Socrates, δηχθε⋯ς ὑπν τ⋯ν φιλοσοφ⋯α λ⋯γων, οἵχονται ⋯γριώτρον.

page 251 note 3 Cf. Tzetzes on Lye. 1113. Aelian compares the two most famous mythological matricides, just as Plutarch (loc. cit.) compared Nero: for all three together, cf. theline quoted in Suet. Nero 39 Ν⋯ρων Ὅρ⋯στης Ἀλκμ⋯νος.

page 251 note 4 The relevance was most clearly stated first by Campbell, A. Y. in C.Q. xxix (1935), 31 ff.Google Scholar, and acknowledged in the Headlam–Thomson Oresteia on Ag. 1231–3 and Cho. 999, and Stanford, Aeschylus in his Style, p. 89; but I find no trace of it in the Fraenkel or Denniston–Page editions of the Agamemnon, and it appears only as an afterthought (without reference to Campbell) in Rose's Commentary, ii p. 228.

page 251 note 5 His σπλ⋯γχνα. makes the image more explicit: in Aesch. Eum. 592 (cf. Eur. El. 1223) the blow is πρ⋯ς δ⋯ρην.

page 251 note 6 Stanford (loc. cit.) comments briefly on Aeschylus' juxtaposition of viper and spider images, as the female spider is another creature devoted to nuptial cannibalism (cf. the name '‘black widow’ given in modern times to the female latrodectus mactans.) Ag. lies ⋯ρ⋯χνης ⋯ν ὐφ⋯ςματι(1492 = 1516), which was described in Cassandra's vision as δ⋯κτυον ἃιδν with Clyt. ἄρκυς⋯ ξ⋯νευνος (1115–6). In Cho. 999–1000, immediately after the echidna passage quoted below, the robe is again called δ⋯κτυον / ἄρκυν (cf. ⋯ρκυωρεῖν of a spider in Ael. V.H. i. 2), and again in Suppl. Aeschylus consecutively likens the sons of Aegyptus to ἄραχνος (887–Tucker conjectured ⋯rho;κυωρ⋯ς in this notably corrupt passage) and δ⋯πους ⋯φις, ἔχιδνα(895–6)—a fact which might commend itself to those who place this play at a period close to the Oresteia. The bites of vipers and spiders occur in juxtaposition in Nic. fr. 31, Plat. Euthyd. 290 a, Dem. xxv. 96.

page 251 note 7 The lioness comparison is, of course, taken directly from the description of Clytemnestra in Ag. 1258, and the other expressions are probably influenced also by the Aeschylean snake imagery (cf. also Eur. I.T. 286 Ἄιδου δρ⋯καινα, Lye. 1113 δρ⋯καινα δ⋯ψας, where Tzetzes glosses ⋯,ντ⋯ το⋯ ⋯ἔχιδνα recounting the Nicandrean story), since συνηρομ⋯νη may have had the associations of the οἰκουρ⋯ς ᾬφις(cf. Ag. 1225 ∘ἰκ∘rρ⋯ν, ∘Ĵμ∘ι, τῷ μ∘λ⋯ντι δεσπ⋯τῃ, ironically of the womanish Aegisthus: both he and Clytemnestra are snakes in Cho. 1047. Lye. 1107 has λυπρ⋯ν λεα⋯νης … οἰκουρ⋯αν of Clytemnestra). Another version of Secundus on Woman in Maximus Confessor, Loci Communes 39 (Migne vol. 91, p. 912) gives σκὺλλα as an alternative forἱματισμ⋯νη ἔχιδνα, which recalls another of Aeschylus' references to Clytemnestra as a ‘Scylla dwelling on the rocks’ (1233). Scylla is coupled with echidna in Plut. Crass., 32 (see C.R. xxxix [1925], 55), and is also a traditional comparison for a courtesan (with echidna, dracaena, in Anaxil. loc. cit.; also Callim. fr. 288, Alciphr. 1. 18. 3, and, by implication, Archil, fr. 15 D.). For another comparison of Scylla and Clytemnestra, see Cho. 612 ff.

page 252 note 1 It is likely that the comparison with the muraena is introduced here along with the echidna because of the belief that the female came on land to mate with the male viper (ἔχις)—see Ael. N.A. i. 50, ix. 66; Nic. Ther. 822 ff., Opp. Hal. i. 554 ff., etc.—and according to Athen. 312 D the offspring of this union are the only ones whose bite is fatal. Doubtless it was this belief too which accounts for the statement of Hierax, περ⋯ δικαιος⋯νης quoted in Stobaeus (iii, p. 428 W.-H.) that they, like the young of the echidna, bite their mother to death before she gives birth.

page 252 note 2 The text is uncertain though the general meaning, attested in the schol., is not in doubt. Among the better remedies (Fraenkel, app. C in Ag. iii, pp. 809–15 regards the lines as the interpolation of a ‘botcher’, Rose invokes a missing line after 994) the following may be cited: (a)θιγο⋯σ ⋯μανλον(Weil)—a rare word not attested in Aesch. (Hsch.⋯μαυλον ⋯μ⋯κοιτον, and cf. ⋯με⋯νου in the echidna passage in Nic. Ther. 131), but supported by ⋯μανλ⋯α (599) where it is used of both κνώδαλα and βροτο⋯ in a theme of overmastering female passion (θ*ηλυκρατ⋯ς ἔρως), and the similarity to this passage (996) is further enhanced by the expressions ὑπ⋯ρτολμον φρ⋯νημα, παντ⋯λμους ἔρωτας (cf. Ag. 1231 τοι⋯δε τ⋯λμα. θ⋯λυς ἄρσενος φονε⋯ς, which precedes the lines where Clyt. is first likened to a snake). This emendation would most satisfactorily complete the echidna allusion (perhaps accepting also Campbell's δακ⋯ν for κακ⋯ν in 993), if the absence of ἄν is considered tolerable; (b)θιγο⋯σ' ἄνθρωπον(i.e. ανον), referred by Rose to E. R. Dodds, but already in Groeneboom's edition—but I doubt if this much improves the unsatisfactory ἄλλον; (c)θιγο⋯ς ἄν μμ⋯λλον ἤ (Paley)— but the combination of nom. and ace. participles seems difficult; (d) μ⋯νον θιγο⋯σ ἄν (Thomson), based on schol.μ⋯νον,⋯ψ⋯μενον which involves both corruption and transposition, but makes satisfactory sense (to his serpent parallels add Ap. Rh. iv. 1512).

page 253 note 1 And would have been particularly familiar to him if she too came from Samos— see Gow, op. cit. ii, p. 4, and for Samian hetairai see another Asclepiades epigram, A.P. v. 150 along with Athen. 220 F, also A.P. v. 44 (Rufinus). The name Philaenion occurs in a few later epigrams (see Headlam on Herod. 1. 5), and is the name of the meretrix in Plaut. Asin., the Greek original of which, by Demophilus, may also have included this name, and probably is contemporary with the floruit of Asclepiades.

page 253 note 2 Note that twice Athenaeus (335 B–E, quoting Chrysippus, and 457 E) classes the books of Philaenis with gastronomical works of Archestratus. The sexual meaning of λαμυρ-⋯ς,-⋯α can best be judged from contexts in which Plutarch uses them—Sull. 35, Luc. 6, Cats. 49, Ant. 24, Mor. 693 c, 1124B: cf. A.P. xii. 109 (Meleager).

page 253 note 3 Cf. Aes. 186 Hausrath, Babr. 143, Phdr. 4. 19, Apost. 13. 79a ⋯ φιντρ⋯φεον, Theogn. 60a, Soph. Ant. 531–3, Cic. Har. Resp. 24. 50, Petron. 77, and (by implication) A.P. xii. 132a 3–4 (Meleager), Artem. ii. 13.

page 253 note 4 See Gow on Machon 175.

page 253 note 5 As does the female viper in Hdt. iii. 109, απτεται τ⋯ς δειρ⋯ς κα⋯ ⋯μφ⋯σα οὐκ ⋯ν⋯ει.

page 254 note 1 It is true, of course, that in Nicander the ‘slumberous lethargy‘ follows the bite.

page 254 note 2 loc. cit. ii, p. 228.

page 254 note 3 It seems to me probable that Lucil. 179–80 M. adsequitur nee opinantem, in caput insilit, ipsum / conmanducatur totutn conplexa comestque (to which Mr. D. A. West has drawn my attention) deals with a comparable situation and theme. Marx however denies the erotic interpretation (which is present in the parallel he cites from Apul. Met. 10. 22).