Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

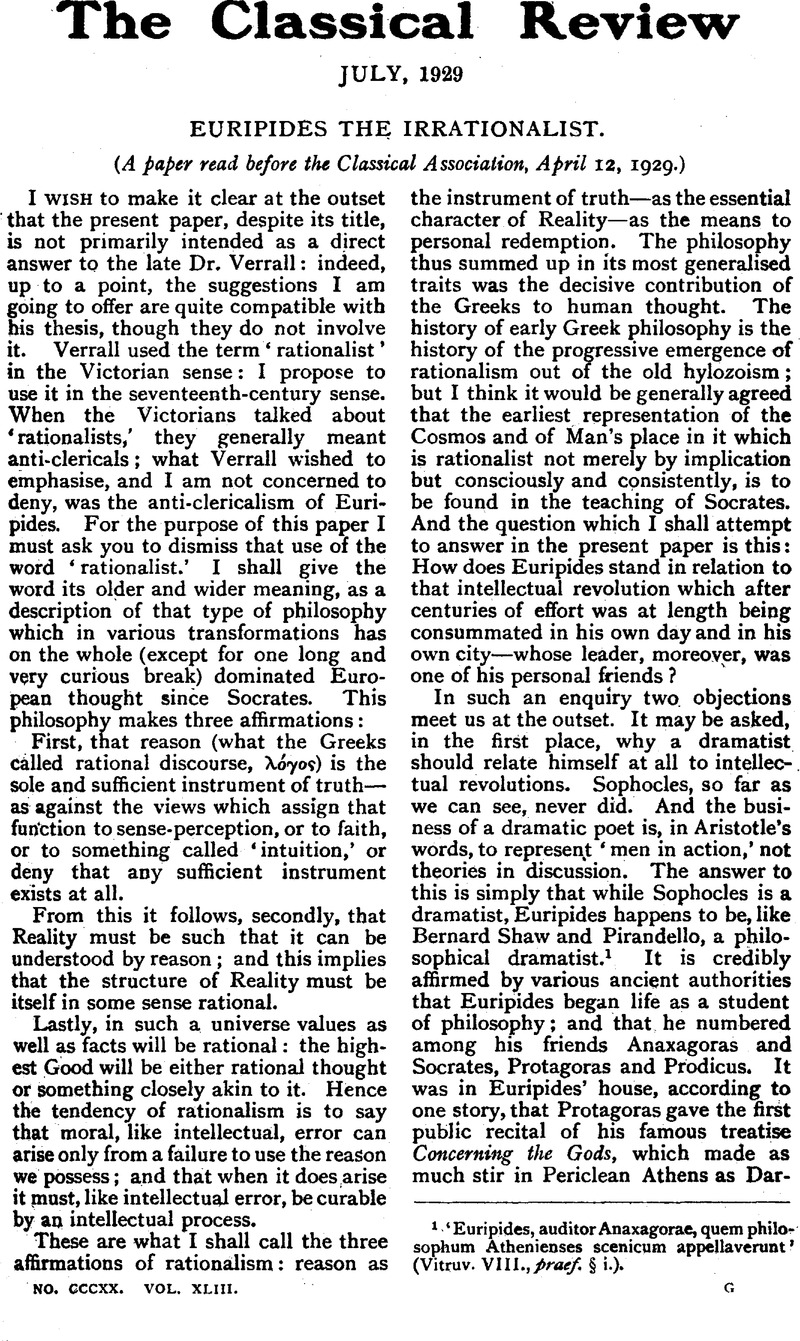

page 97 note 1 ‘Euripides, auditor Anaxagorae, quern philosophum Athenienses scenicum appellaverunt’ (Vitruv. VIII., praef. § i.).

page 98 note 1 Hec. 592 ff.

page 98 note 2 Ale. 962.

page 98 note 3 Med. 1383.

page 99 note 1 Ibid. 1056–7.

page 99 note 2 Ibid. 1333.

page 99 note 3 Hipp. 79 f.

page 99 note 4 Ibid. 921–2.

page 99 note 5 Ibid. 375.

page 99 note 6 Ibid. 380 ff.

page 99 note 7 Ibid. 358.

page 99 note 8 Ibid. 756 ff.

page 99 note 9 Cf. e.g. frs. 576, 837–8 (the numeration followed is that of Nauck's second edition).

page 99 note 10 Hec. 899.

page 99 note 11 Frs. 344, 807, 1053.

page 99 note 12 911 ff.

page 99 note 13 Hipp. 198–251. Cf. C.R. XXXIX., 1925, 102.

page 99 note 14 Bacch. 1264–84. Noteworthy here are (1) the amnesia which comes on in verse 1272 (as with patients awakening from an hypnotic trance), and the gentle skill with which Cadmus reinstates the lost memory by the help of association ; (2) Agave's attempt to retreat into her dream rather than face the truth of which she is already subconsciously aware (1278; cf. 1107–9, where Pentheus is simultaneously thought of as an animal and as a human spy, and the similar clash of dream and reality in Pentheus’ own mind, v. 922).

page 100 note 1 Fr. 189.

page 100 note 2 Fr. 170.

page 100 note 3 Hec. 814 ff.

page 100 note 4 Fr. 205.

page 100 note 5 Fr. 652.

page 100 note 6 Med. 1225 ; cf. Hec. 1192.

page 100 note 7 1617.

page 100 note 8 H.F. 669; cf.Med. 516, Hipp. 925.

page 100 note 9 379.

page 100 note 10 Hipp. 428, etc.

page 100 note 11 539.

page 100 note 12 305.

page 100 note 13 294 ff.; cf.fr. 636.

page 100 note 14 294 ff.

page 100 note 15 115.

page 101 note 1 Fr. 201.

page 101 note 2 Or. 418.

page 101 note 3 965 ; cf. Hel. 513 f., and the repeated insistence that Man is subject to the same cycle of physical necessity as Nature, frs. 332, 419, 757.

page 101 note 4 Fr. 869; cf. 836, 911, 935.

page 101 note 5 Tr. 885 :

![]() The interpretation I have ventured to give to the ambiguous νο⋯ς βροτ⋯ν is supported by v. 988, where the same speaker tells Helen that her own corrupt mind (νο⋯ς) turned into Aphrodite : Aphrodite is only a hypostatised lust, and Zeus himself may be a like figment. The famous line

⋯ νο⋯ς γ⋯ρ ἠμ⋯ν ⋯στιν ⋯ν ⋯κ⋯στῳ θε⋯ς (fr. 1007)

is similarly ambiguous. Nemesius (Nat. Hom. 348) took it to mean

The interpretation I have ventured to give to the ambiguous νο⋯ς βροτ⋯ν is supported by v. 988, where the same speaker tells Helen that her own corrupt mind (νο⋯ς) turned into Aphrodite : Aphrodite is only a hypostatised lust, and Zeus himself may be a like figment. The famous line

⋯ νο⋯ς γ⋯ρ ἠμ⋯ν ⋯στιν ⋯ν ⋯κ⋯στῳ θε⋯ς (fr. 1007)

is similarly ambiguous. Nemesius (Nat. Hom. 348) took it to mean ![]() . Is this ‘paltering in a double sense’ deliberate and prudential? Cf. also the much discussed lines Hec. 799–801, where Hecuba seems to say that the gods are the servants (or symbols ?) of the Law of Justice which governs human society, and that religion derives its strength from morality. Whether the ‘Law’ is meant to be cosmic as well as human, I cannot feel sure.

. Is this ‘paltering in a double sense’ deliberate and prudential? Cf. also the much discussed lines Hec. 799–801, where Hecuba seems to say that the gods are the servants (or symbols ?) of the Law of Justice which governs human society, and that religion derives its strength from morality. Whether the ‘Law’ is meant to be cosmic as well as human, I cannot feel sure.

page 101 note 6 793 ; cf. also 395, 483.

page 102 note 1 360.

page 102 note 2 447.

page 102 note 3 1441.

page 102 note 4 75, θιασε⋯εται Ψυχ⋯ν : the rendering is Verrall's.

page 102 note 5 726, π⋯ν δ⋯ συνεβ⋯κχευ' ⋯ρος κα⋯ θ⋯ρες.

page 102 note 6 115, Βρ⋯μιος ὅστις ἄγ⋯ θι⋯σους (I accept Murray's reading and interpretation of the line).

page 102 note 7 395.

page 102 note 8 Or, rather, not a parallel but an echo; for it was Professor Murray's translation of the Bacchae which set Shaw exploring the truncated manifestations of orgiastic religion in our own day.

page 103 note 1 Fr. 475.

page 103 note 2 Hipp. 120.

page 103 note 3 Bacch. 1348.

page 103 note 4 Cf. especially the remarkable fragment 508 (which should perhaps be brought into connection with Hec. 799–801).

page 103 note 5 I.T. 572.