No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

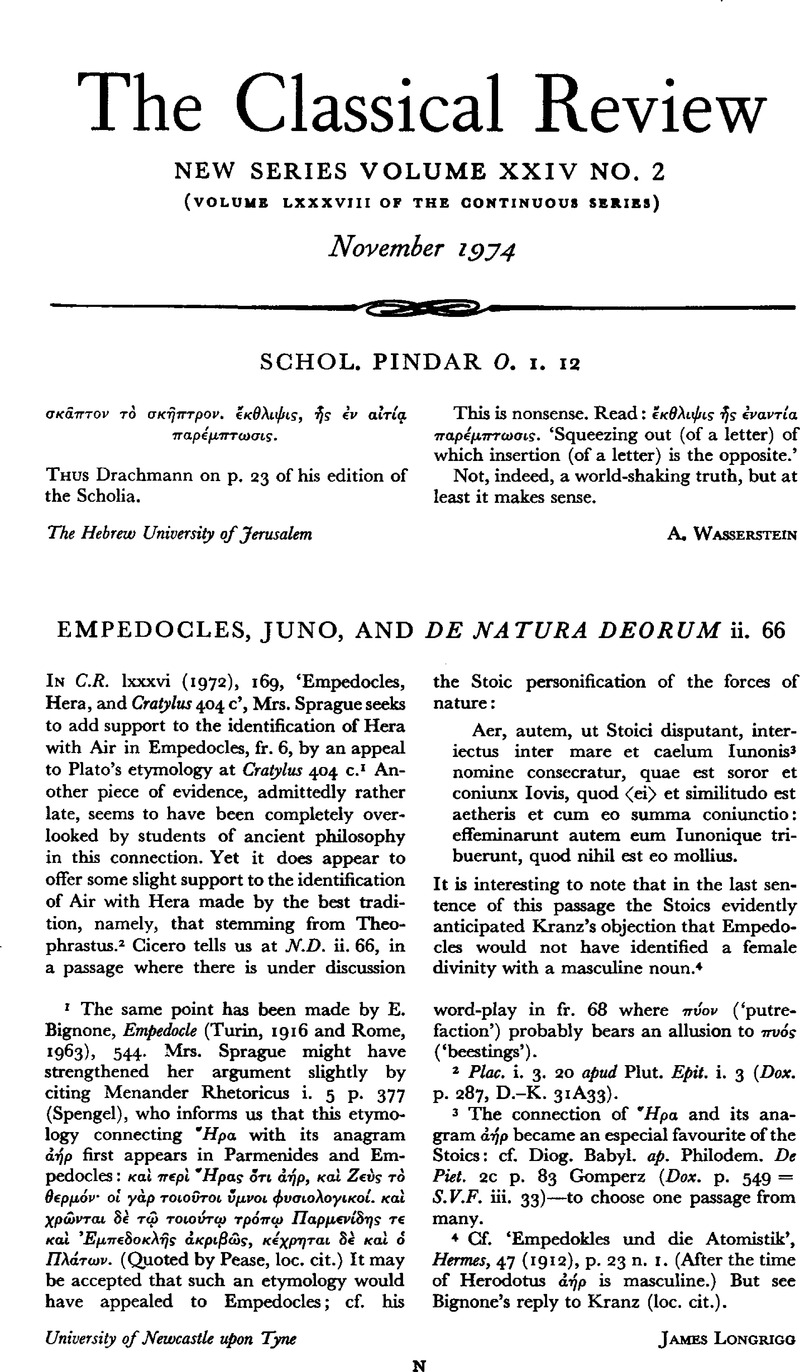

Empedocles, Juno, and De Natura Deorum ii. 66

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1974

References

1 The same point has been made by E. Bignone, Empedocle (Turin, 1916 and Rome, 1963), 544. Mrs. Sprague might have strengthened her argument slightly by citing Menander Rhetoricus i. 5 p. 377 (Spengel), who informs us that this etymology connecting Ηρα with its anagram ⋯⋯ρ first appears in Parmenides and Empedocles: κα⋯ περ⋯ Ἤρας ⋯τι ⋯⋯ρ, κα⋯ Ζε⋯ς τ⋯θερμ⋯ν οἱ γ⋯ρ τοιο⋯τοι ὔμνοι φυσιολογικο⋯. κα⋯χρ⋯νται ς⋯τῷ τοιο⋯τῳ τρ⋯πῳ Παρμεν⋯δης τεκα⋯ Ἐμπεδοκλ⋯ς ⋯κριβ⋯ς, κ⋯χρηται δ⋯ κα⋯ ⋯Πλ⋯των. (Quoted by Pease, loc. cit.) It may be accepted that such an etymology would have appealed to Empedocles; cf. his word-play in fr. 68 where π⋯ον (‘putrefaction’) probably bears an allusion to πυ⋯ς (‘beestings’).

2 Plac. i. 3. 20 apud Plut. Epit. i. 3 (Dox. p. 287, D.-K. 31A33).

3 The connection of Ηρα and its anagram ⋯⋯ρ became an especial favourite of the Stoics: cf. Diog. Babyl. ap. Philodem. DePiet. 2c p. 83 Gomperz (Dox. p. 549 = S.V.F. iii. 33)—to choose one passage from many.

4 Cf. ‘Empedokles und die Atomistik’, Hermes, 47 (1912), p. 23 n. 1. (After the time of Herodotus ⋯⋯ρ is masculine.) But see Bignone's reply to Kranz (loc. cit.).