Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

page 1 note 2 Plut. Quaest. conv. 677D. Simpl. Phys. 24; De caelo 529. 14. Athen. x. 423F. Eustathius, , in Horn. Il. (Leipzig, 1828), vol. 2, p. 255. 8.Google Scholar

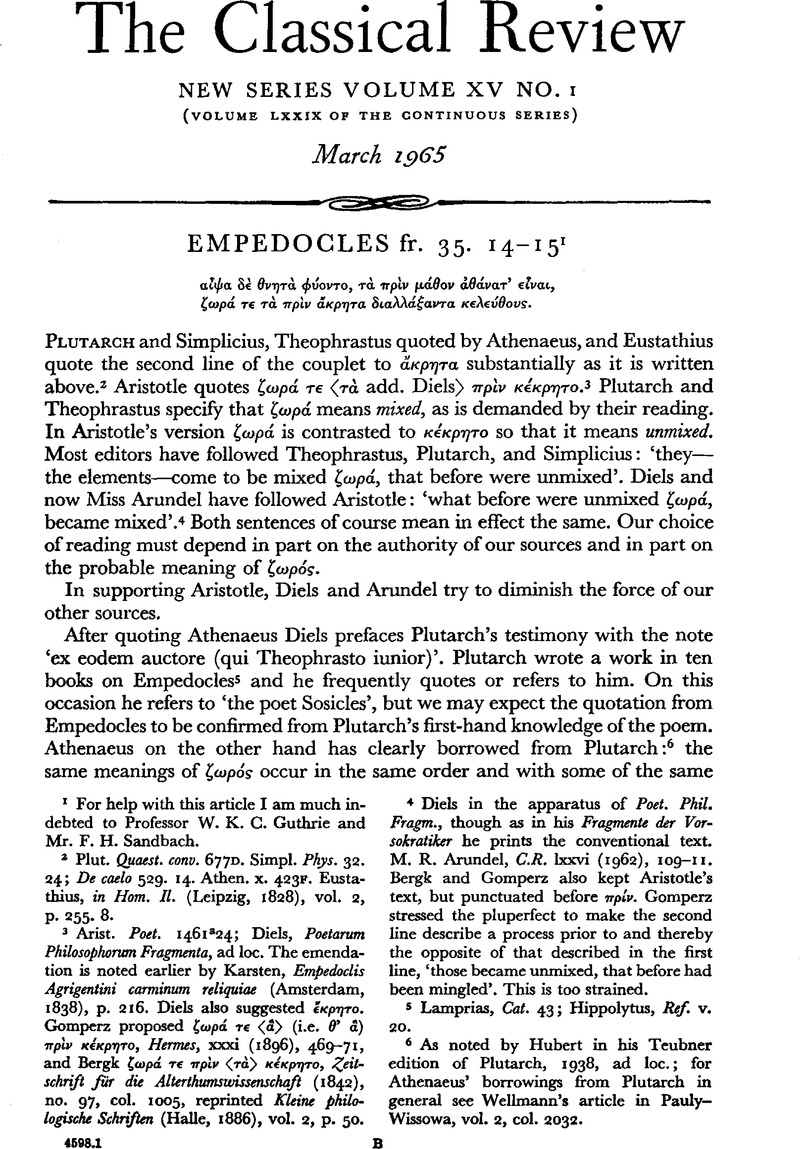

page 1 note 3 Arist. Poet. 1461a24; Diels, Poetarum Philosophorum Fragmenta, ad loc. The emendation is noted earlier by Karsten, , Empedoclis Agrigentini carminum reliquiae (Amsterdam, 1838), p. 216.Google Scholar Diels also suggested ἔκρητο. Gomperz proposed ξωρά τε 〈ἃ〉 (i.e. θ᾽ ἃ) πρὶν κέκρητι, Hermes, xxxi (1896), 469–71, and Bergk ξωρά τε πρὶν 〈τὰ〉 κέκρητο, Zeitschrift für die Alterthumswissenschaft (1842), no. 97, col. 1005, reprinted Kleine philologische Schriften (Halle, 1886), vol. 2, p. 50.

page 1 note 4 Diels in the apparatus of Poet. Phil. Fragm., though as in his Fragmente der Vorsokratiker he prints the conventional text. Arundel, M. R., C.R. lxxvi (1962), 109–111Google Scholar. Bergk and Gomperz also kept Aristotle's text, but punctuated before πρί. Gomperz stressed the pluperfect to make the second line describe a process prior to and thereby the opposite of that described in the first line, ‘those became unmixed, that before had been mingled’. This is too strained.

page 1 note 5 Lamprias, Cat. 43; Hippolytus, Ref. v. 20.

page 1 note 6 As noted by Hubert in his Teubner edition of Plutarch, 1938, ad loc.; for Athenaeus' borrowings from Plutarch in general see Wellmann's article in Pauly-Wissowa, vol. 2, col. 2032.

page 2 note 1 For Athenaeus' frequent use of Theophrastus, see the index to the Teubner edition of Athenaeus, 1890.

page 2 note 2 Empedocles fr. 21.14 quoted Simpl. Phys. 159. 26; fr. 22. 7 quoted Simpl. Phys. 161. 5 (cf. Theophrastus, De sensu 16); fr. 128. 8 quoted Porph. De abst. ii. 21 and 27 (cf. Eusebius, , Praep. Evang. iv. 14Google Scholar); Parmenides fr. 12. 1 quoted Simpl. Phys. 39. 14 (here the form in ι is corrected to ν by the second hand in E, which, according to Diels, Introduction to the Berlin edition, p. vii, represents an exemplar of outstanding excellence older than the archetype of the remaining manuscripts).

page 2 note 3 Simplicius' independence is shown by the extent of his quotations from Empedocles (they account for from seven to eight per cent, of the whole poem) and by his referring to parts and books of the physical poem, e.g. Phys. 32. 11; 33. 18; 157. 27; 161. 15; 300. 20; 331. 13; 381. 29; De caelo 529. 24; 530. 5. Eustathius is another matter. He knew Plutarch's Quaest. conv.; see Hudson's Index scriptorum ab Eustathio citatorum in Fabricius–Harles, Bibliotheca Graeca (4th edition, Hamburg, 1790), vol. 1, pp. 457 ff.Google Scholar But his quotation of Empedocles is longer than Plutarch's. It may come from Athenaeus, one of Eustathius' regular sources; see Hudson's Index and Cohn's article in Pauly–Wissowa, vol. 6, col. 1482, cf. col. 1459.Google Scholar

page 2 note 4 Plato, Laws 637 e; Herodotus vi. 84; Athenaeus ii. 38c–D.Google Scholar

page 2 note 5 The context in Athenaeus shows that the intended positive is ἄκρατος, not ἀκρατής. The same use of ἀκρατέστερος is especially clear at [Arist.] Problem. 871a16–22 and 873a4–12. For similar examples of ‘crossed’ comparatives see Kühner–Blass, i. 562–3, and Schwyzer, i. 535.

page 2 note 6 This is the opinion of Tkatsch, Die arabische Übersetzung der Poetik des Aristoteles, Wien und Leipzig, 1932, vol. 2, p. 129b.Google Scholar

page 3 note 1 This agrees with the derivation of the word; see Schwyzer, , Griechische Grammatik, i. 330Google Scholar. It also gives good sense to μελίξωρονποτόν, ‘like a strong, concentrated honey drink’, Phaedimus ap. Athen. xi. 498E and Nicander, Alex. 351;Google Scholar cf. 205, where μελίξωρος is explained by the scholiast as μελίκρατος, Schol. vet. in Nic. Alex., Ábel–Vári, Budapest, 1891. Ζωρός cannot here mean unmixed, for wholly undiluted honey would be hardly drinkable. Alternatively, the scholiast may be right, and Nicander drawing from Empedocles or from Homer.

page 3 note 2 Xenophanes fr. 5; Anacreon fr. 33 Gentili (Rome, 1958); Hesiod, Op. 596 (the passage is marked by Paley as ‘a manifest interpolation’, but it is of some antiquity since it is quoted by Athenaeus x, 426c); cf. Pherecrates fr. 70: i. 164 Kock. This point is made by Panzerbieter, , Beiträge zur Kritik und Erklärung des Empedokles (Meiningen, 1844), p. 32.Google Scholar

page 3 note 3 Empedocles may well himself have invented ξωρός from the comparative in Homer, just as he may well have invented θέλυμνα fr. 31. 6 (the reading is disputed) from the Homeric προθέλυμνος and τετραθέλυμνος, or ὄΦ fr. 88 from the oblique cases in Homer, or ἀνόπαιον fr. 51 from Homer's ἀνοπαῖα. There are some forty words used only by Empedocles or found in him for the first time, and it is a fair assumption that a number of these are his inventions.

page 3 note 4 I note as examples only: φύσις οὐδενὸς ἔστιν ἐόντων for ψύσις οὐδενὸς ἔστιν ἁπάντων θνητῶν, Met. 1015a 1, fr. 8; ἐξ ὧν πάνθ᾽ ὄσατ᾽ ἦν ὅσα τ᾽ ἔσθ᾽ ὅσα τ᾽ ἔσται ὀπίσσω for ἐκτούτων γάρ πάνθ᾽ ὅσα τ᾽ ἢν ὅσα τ᾽ ἔστι καὶ ἔσται, Met. 1000a29, fr. 21. 9.

Tkatsch, op. cit., pp. 128–31, argues that the criticism of Empedocles implied in the Poetics is the use of ξωρός to mean mixed; and that this Aristotle corrects by adopting the alternative punctuation and by deliberately altering ἄκρητα to κέκρητο. It is simpler to suppose, as we have done, that the ἐπιτίμημα is the ambiguous punctuation, not the misuse of ξωρός.

page 3 note 5 διαλλάξαντα in Simplicius, διαλλάσσοντα in Athenaeus.

page 3 note 6 Aristotle, on coming-into-being and passing-away: some comments, in Philosophia Antiqua, i (Leiden 1946), pp. 66–67.Google Scholar

page 4 note 1 In the continuation of the passage quoted Diels, , Fragm. d. Vors. i. 183. 29Google Scholar, has restored ὁκόσα διαλλάσσει (manuscripts δὲ ἄλλως) ἀπ᾽ ἀλλήλων, ὑπὸ βίης ἀποκρίνεται, an emendation which if accepted would show that the two verbs were not synonymous, ‘in so far as they are different from one another, they are forcibly kept apart’. Verdenius also adduces διάλλαξις at De victu i. 10 (vi. 486 Littré), but there it is in a list of the properties of fire, and there is no way of determining its precise significance. Αὔξησις, κίνησις, μείωσις immediately precede, and Littré translates ‘la permutation’.

page 4 note 2 That is the interpretation of the ancient authorities who quote the line, Plut. Adv. Col. 1112A; Simpl. Phys. 161. 18, 180. 28, 235. 21; Aet. i. 30. 1; Pseud. Arist. De MXG 975b6 (where there is the paraphrase διαλλαττομένων τε καὶ διακρινομένων). But implication is less obvious than they suppose, for Empedocles did not himself make a strict correlation between birth and mixture, death and separation; see fr. 17. 4–5.

page 4 note 3 Διαλλάσσοντα is not a chance variant τάδ᾽ ἀλλάσσοντα in the parallel passage fr. 26. 11, at least not in Simplicius' exemplar, for he consistently quoted the former as part of fr. 17, Phys. 158. 1; De caelo 141. 1, 293. 25 (the two last are shown to be fr. 17 because of the lacuna after v. 8 and because of εἰς έν ἅπαντα not εἰς ἕνα κόσμον in v. 7), and the latter as part of fr. 26, Phys. 33. 19, 160. 20, 1125. 1 (the two last are shown to be fr. 26 because in the first case he has just quoted vv. 1–2 of that fragment and in the second case he is commenting closely on Aristotle's quotation with τάδ᾽ ἀλλάσσοντα presumably of that fragment). The use of the two verbs interchangeably in a set of repeated verses shows that διαλλάσσοντα has not become restricted to a special sense.

page 4 note 4 We may also compare the similar phrase μεταλλάσσοντα κελεύθους, fr. 115. 8, which likewise refers to change in general, not to separation. If διαλλάσσειν is not to be taken as neutral, it could be given the fairly common connotation of ‘reconciliation’; for references see L.S.J. The elements ‘reconcile their ways’ because they change from being separated to being mixed.