No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

The Emendation of the Text of Nonius

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1902

References

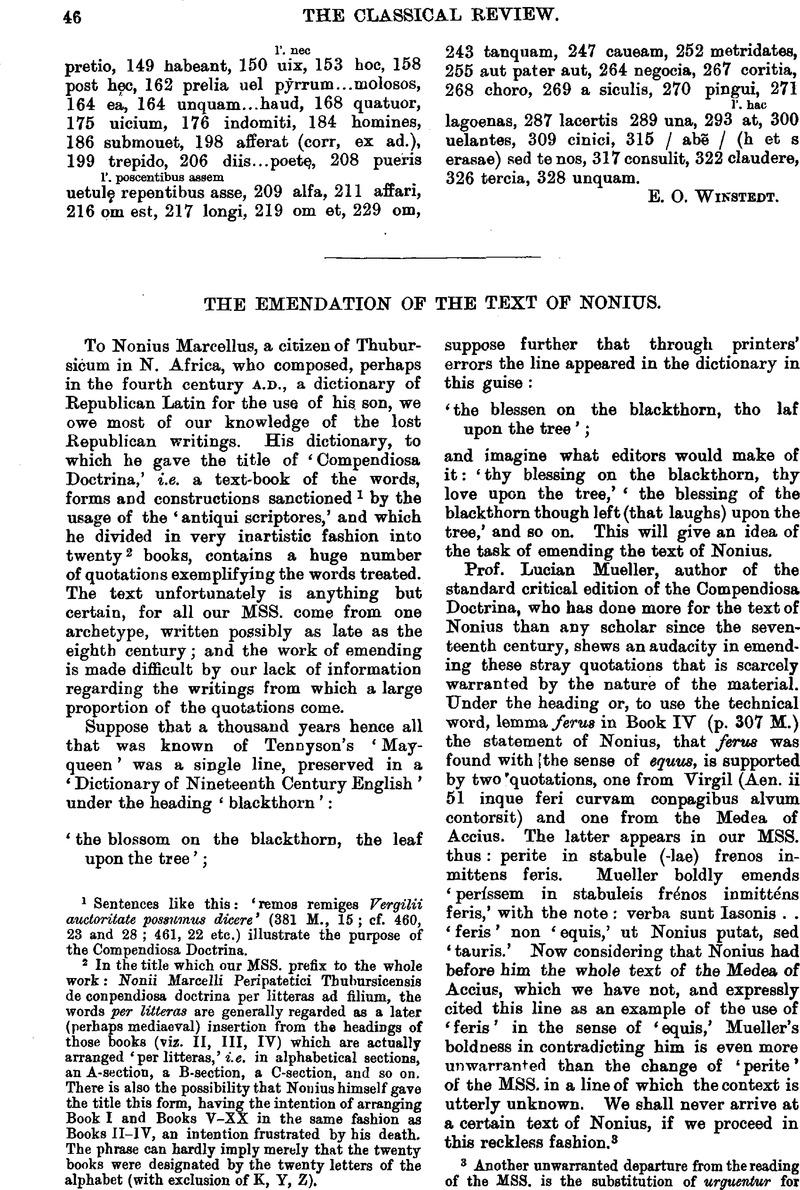

page 46 note 1 Sentences like this: ‘remos remiges Vergilii auctoritate possumus dicere’ (381 M., 15; cf. 460, 23 and 28; 461, 22 etc.) illustrate the purpose of the Compendiosa Doctrina.

page 46 note 2 In the title which our MSS. prefix to the whole work: Nonii Mareelli Peripatetici Thubursicensis de conpendiosa doctrina per litteras ad filium, the words per litteras are generally regarded as a later (perhaps mediaeval) insertion from the headings of those books (viz. II, III, IV) which are actually arranged ‘per litteras,’ i.e. in alphabetical sections, an A-section, a B-section, a C-section, and so on. There is also the possibility that Nonius himself gave the title this form, having the intention of arranging Book I and Books V–XX in the same fashion as Books II–IV, an intention frustrated by his death. The phrase can hardly imply merely that the twenty books were designated by the twenty letters of the alphabet (with exclusion of K, Y, Z).

page 46 note 3 Another unwarranted departure from the reading of the MSS. is the substitution of urguentur for urguemur in a line, apparently of Ennius (ap. Non. 418, 12): quamurum fieri voluit, urguemur in nnum. Since the context is unknown, what warrant is there for the change? Suppose, for example, the words to be uttered by Remus. Would not urguemur be perfectly natural?

page 47 note 1 Full details, along with an analysis of the Compendiosa Doctrina, are given, in my ‘Nonius Maroellus’ (Oxford, 1901).

page 47 note 2 The similar treatment of the verb grundire by Nonius in a lemma taken from this glossary (465, 1; cf. 114, 26–29) and by Diomede is noticeable.

page 48 note 1 Prof. Havet (Mél. Graux, p. 804) thinks it possible that mediaeval scribes may have adapted a line in one passage to its form in another, even widely removed, passage. I doubt whether mediaeval scribes would be likely to be so painstaking.

page 48 note 2 The analysis of Book III is made difficult by the shortness of its sections. Still we get in many parts of the book so clear indication of Nonius' regular use of his ordinary sources that I can see no ground for supposing Nonius to have borrowed his material for this particular book from a Grammarian. At the same time the treatment of a word by a Grammarian often helps us to emend the text of a corresponding passage of Nonius, not merely in this book but in others. Thus Charisius (201 K. 17) says that ilico was used by Plautus, etc. for in loco. Nonius in Book IV ‘De Varia Significatione Sermonum’ gives Several meanings of ilico, each illustrated by quotations. At 325, 4 the MSS. offer: Ilico, illo. Turpilius Leucadia: ‘sed quam longe est cum isti ilico.’ The statement of Charisius suggests the emendation: Ilieo, in loco. Turp. Leuc.:

A. Sed quám longe? B. Eccum isti ílico, retaining longe in its sense of place.‘not of time. This, however, involves too violent a departure from the MSS. to be convincing. If Nonius’ use of Gellius in this book begins at p. 195 with the lemma cor, it may be that not merely the following lemma cupressus, but also the next, carra come from the same source. If so, this is a striking confirmation of Scaliger's emendation petorrita in 195, 27 (cf. Gell. XV 3O).

page 49 note 1 Plaut. Anl. 15–17 is broken up by Nonius in this way:

(s.v. observare, 360, 1)

ubi is óbiit mortem, quí mi id aurum crédidit, coepi óbservare,

(s.v. honor, 320, 18)

ecqui maiorem filus mihi honórem haberet quám eius habuissét pater.

page 50 note 1 The formula used for Latin ‘Wellerisms,’ e.g. Plaut. Cist. 14:

Quód Ille dixit, quí secundo vénto vectus ést tranquilló mari,

Véntum gaudeo.

page 50 note 2 The actual words would probably be words quite unconnected with the meaning of the part quote. Otherwise Nonius would be likely to have includ them in the quotation. This consideration has been strangely neglected by editors (see Ribbeck's Dramatic Fragments passim).

page 51 note 1 Unless it is in reality a mediaeval interpolation.